Clinical safety or patient safety is now recognised as a critical aspect of healthcare, and since the publication of To err is human: Building a safer health system in the late 1990s, it has been considered a global priority.1 Since then, work has intensified in this regard, being progressively incorporated in health policies. In our setting, patient safety has been included in all the quality plans of the Autonomous Communities. In 2005, the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality, in collaboration with the autonomous communities, started to develop the patient safety strategy of the National Health Service, based on recommendations made internationally and by Spanish experts. In the same vein, the “National Health Service's Patient Safety Strategy 2015–2020” is aimed at promoting and improving the culture of safety in healthcare organisations, incorporating health risk management, training professionals and patients in basic aspects of patient safety and implementing safe practices, involving patients and citizens.2

A culture of clinical safety is a complex phenomenon involving elements such as leadership, teamwork, evidence-based medicine, communication, learning, and patient-centred practice.3 Promoting this culture is of special interest in specialties such as gynaecology and obstetrics that involve a dual risk for maternal and foetal health. In fact, many measures have been taken in this area to improve clinical safety. There have even been voices that warn of defensive practices that could be counter-productive, such as an increase in the percentage of caesareans.4

One of the strategies suggested in 1999 by the United States National Academy of Medicine for improving patient safety was mandatory reporting of care-related incidents.1 This publication emphasised that healthcare organisations should promote a culture of clinical safety, in which adverse events are recorded without blaming the protagonists, thus enabling professionals to learn from errors and to prevent future mistakes.1 In this regard, in the specialties of obstetrics and gynaecology, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) promotes the concept of a “culture of justice”, which states that highly competent doctors can also make mistakes.5 By avoiding a punitive response, the system might support professionals who report adverse events, under the premise that such a register would help to achieve a safer practice of medicine.6 Thus, in 2003 the British National Health Service (NHS) created a database for recording incident reports (the National Reporting and Learning System [NRLS]), considered the world's largest repository of such adverse events.

However, such registers run into difficulties, both in implementation and in functioning, regarding the professionals’ culture of patient safety. In the absence of registers and/or complementary methods, there are other viable options for clinical safety.7,8 Thus, the NHS also uses claims analysis as a source of systematic learning through its Litigation Authority (NHSLA).9 In our setting, the Catalan model for medical professional liability insurance considers this analysis to be one of its essential elements and contains a co-operation agreement on these lines with the Spanish Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics.10,11

In the specialties of gynaecology and obstetrics, this type of analysis is especially important in terms of learning, since they are invariably indicated as being at a high risk of claims by publications inside and outside our borders.12–14 Apart from its obvious potential as a source of learning, the cost associated with these claims for alleged medical professional liability is extremely high for the system. The NHSLA warns that these claims are the cause of higher-cost claims in the NHS, with future increases expected in amounts awarded for compensation.9 In fact, the publications focused on the highest payments for claims due to medical professional liability underscore the significance of the specialties of obstetrics and gynaecology as being associated with the highest percentage of “catastrophic” compensation.15,16

As mentioned above, the literature assigns obstetrics a primary role in claims due to alleged malpractice, in terms of frequency and rates of conviction or settlement, and the amounts awarded for compensation,12–16 thus making the analysis of the case series especially relevant. There are general international measures in terms of clinical safety, which are also applicable in gynaecology and obstetrics, such as the use of checklists. From a clinical point of view, according to data from claims analysis, clinical-safety efforts should focus on preventing incidents associated with childbirth care, which would include cases related to the interpretation of cardiotocographic tracing and caesarean times.9 Measures such as continuous training for professionals—especially in interpreting cardiotocography—are recommended to promote effective communication between midwives, doctors and patients, comply with the updated guidelines on managing routine situations, and make available protocols for handling emergencies.9 From the point of view of professionals’ legal safety, there are also relatively simple measures that would be extremely useful. Thus, in childbirth care, attention should be paid to adequately documenting cardiotocographic records, by identifying the patient, the date and the time in an appropriate manner, as well as any incidents, and by involving different agents in their interpretation. Other common allegations in international claims relate to multiple pregnancies,17 prematurity,18 obstetric ultrasound19 and foetal monitoring.20 Shwayder described nine major areas of claims in obstetrics: error or omission in screening and prenatal diagnosis, ultrasound diagnosis, newborns with neurological involvement, neonatal encephalopathy, foetal or neonatal death, shoulder dystocia, vaginal delivery after caesarean section, operative vaginal delivery and training programmes.21 Also, in our setting, the majority of claims are related to childbirth care.13 We have already mentioned that this factor, apart from other considerations regarding patient safety, has been indicated as promoting high rates of caesarean section, even in low-risk deliveries.22 However, suboptimal results after caesarean section are also the subject of claims in our setting.13

In gynaecology, the Physician Insurers Association of America (PIAA) has pointed out that breast cancer was the diagnosis most frequently involved in claims for alleged malpractice, although these claims are often directed towards radiologists.23 Our data are consistent with the relevance of this diagnosis as a reason for claims, but rates of conviction or settlement are low.13 By contrast, some surgical procedures, such as hysterectomy, also feature a frequency of claims that merits special mention, and others, such as foreign objects left in the body, show high rates of conviction or compensation agreement.13

The importance of procedures in gynaecology and obstetrics exceeds the scope of their roles, since childbirth care has been identified as a risk area for claims due to medical professional liability for other specialists involved in them. In our setting, the role of the anaesthesiologist in childbirth care is an example, which has also been emphasised as involving risk.24

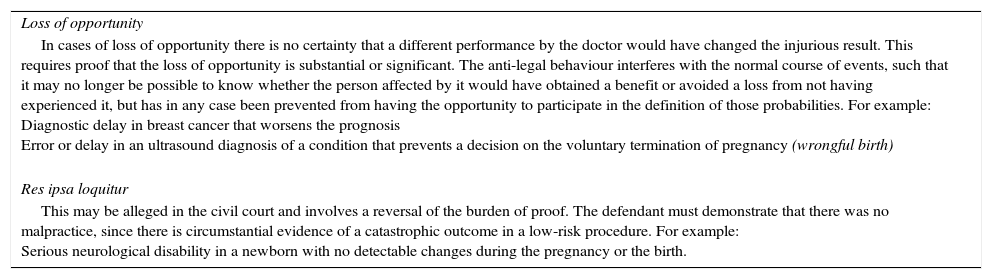

Likewise, we must highlight some jurisprudential concepts, of special relevance in the specialties of gynaecology and obstetrics, which condition the concurrence of professional responsibility in certain cases, as shown in Table 1. Some of these concepts, closely related to gynaecology and obstetrics, have been the subject of specific publications in the “Revista Española de Medicina Legal” and in other specialised scientific journals.13,25,26

Relevant jurisprudential concepts in medical professional liability in gynaecology and obstetrics.

| Loss of opportunity |

| In cases of loss of opportunity there is no certainty that a different performance by the doctor would have changed the injurious result. This requires proof that the loss of opportunity is substantial or significant. The anti-legal behaviour interferes with the normal course of events, such that it may no longer be possible to know whether the person affected by it would have obtained a benefit or avoided a loss from not having experienced it, but has in any case been prevented from having the opportunity to participate in the definition of those probabilities. For example: Diagnostic delay in breast cancer that worsens the prognosis Error or delay in an ultrasound diagnosis of a condition that prevents a decision on the voluntary termination of pregnancy (wrongful birth) |

| Res ipsa loquitur |

| This may be alleged in the civil court and involves a reversal of the burden of proof. The defendant must demonstrate that there was no malpractice, since there is circumstantial evidence of a catastrophic outcome in a low-risk procedure. For example: Serious neurological disability in a newborn with no detectable changes during the pregnancy or the birth. |

This issue of the “Revista Española de Medicina Legal” once again dedicates one of its articles to professional responsibility, thus emphasising its importance in high-risk specialties, such as gynaecology and obstetrics. In this article, García-Ruíz et al. analyse criminal proceedings for these types of procedure and indicate the frequency of claims related to childbirth care, and its higher rates of conviction, especially in cases of neurological damage.27 Criminal proceedings, in addition to recent legislative changes, continue to expose doctors to the risk of convictions involving disqualification and custodial sentences.28 The results of García-Ruíz et al. confirm the national and international findings in this regard and provide information of great interest to gynaecologists and obstetricians, who are particularly exposed in terms of criminal proceedings.27

These articles and editorials are aimed at disseminating data of great relevance to practitioners, patients and society as a whole, thereby contributing to safer healthcare.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-Durán EL, Lailla-Vicens JM, Arimany-Manso J. Seguridad clínica y responsabilidad profesional en ginecología y obstetricia. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2016;42:133–135.