The forensic-psychiatric assessment of the risk of terrorist radicalisation in the mentally ill patient is of special interest for the evaluation of criminal dangerousness. This particularly relevant in ligh of the recent investigations into so-called lone-wolves, which indicate a high prevalence of mental illness within this type of terrorist.

MethodologyAnalysis of the predictive validity of the Terrorist Radicalisation Assessment Protocol (TRAP-18) to predict future violent incidents of an extremist nature in a representative sample of 44 patients with severe mental illness in situations of social exclusion and with a prison history.

ResultsThe ROC Curves analysis indicated that the total score of TRAP-18 (AUC 1.00, p=.018) has a high predictive validity.

ConclusionsTRAP-18 could be a useful tool for assessing the risk of terrorist radicalisation in the mentally ill patient, especially in the group of people with severe mental illness in situations of social exclusion and with a prison record, who have a greater potential risk of terrorist radicalistion as lone-wolves.

La valoración psiquiátrico-forense del riesgo de radicalización terrorista en el enfermo mental tiene especial interés para la evaluación de la peligrosidad criminal; especialmente a raíz de las recientes investigaciones sobre los denominados lobos solitarios, que indican una elevada prevalencia de enfermedad mental dentro de este tipo de terroristas.

MetodologíaAnálisis de la validez predictiva del Protocolo de Evaluación de Radicalización Terrorista (TRAP-18) para predecir futuros incidentes violentos de carácter extremista en una muestra representativa de 44 pacientes con trastorno mental grave en situación de exclusión social y con antecedentes penitenciarios.

ResultadosEl análisis de curvas ROC indicó que la puntuación total de la TRAP-18 (AUC 1,00, p=0,018) tiene una alta validez predictiva.

ConclusionesEl TRAP-18 podría resultar una útil herramienta para la valoración del riesgo de radicalización terrorista en el enfermo mental; especialmente en el colectivo de personas con trastorno mental grave en situación de exclusión social y con antecedentes penitenciarios, los cuales presentan un mayor riesgo potencial de radicalización terrorista como lobos solitarios.

The association between mental illness and terrorist radicalisation is controversial, and extremely topical. There have been different stages in the attempt to understand what motivates the terrorist. In the nineteen seventies, the emphasis was placed on the pathological features of the terrorist's personality.1 In the eighties psychoanalytical approaches came more to the fore, but the studies that appeared at the end of the nineteen nineties dismissed these as lacking in scientific rigour.1,2 And over the past two decades, based on research undertaken on different terrorist groups (such as ETA, the IRA, Hezbollah, the National Liberation Front, Colombian terrorist groups, Palestine terrorist groups, and jihadists), there is now consensus on the origin of terrorist motivation with the emphasis on group dynamics (i.e., social in addition to individual factors).1–4

Until recently, the role of mental illness has been minimised, and it has even been claimed that mentally ill people, by definition, could not be terrorists.5 This makes some sense; leaders of terrorist groups tend to stress the importance of ideological and religious views and the ability in particular to acquire specialist skills, in combat, logistics, propaganda, etc. Therefore terrorist groups in general have shown little interest in recruiting the mentally ill, who could prove unstable and difficult to control. However, this style of organisational preference seems to have been changed, essentially by the self-proclaimed Islamic State who put forward a “do it yourself” approach using the social networks, promoting the figure of the so-called lone wolf and emphasising lone terrorism (a term used to distinguish the violent acts carried out in support of a group, movement or ideology by a single individual, with no direction of an external group.

In this regard, in light of new research on the lone terrorist,6,7 authors like Corner and Gill1,8 suggest that mental illness should be revisited as part of the process through which some people become involved in terrorism; since recent studies suggest that there is a higher prevalence of mental illness in these types of terrorists than that observed in terrorist groups or cells (40% vs. 7.6%).7

Therefore, although mental illness cannot be considered a cause of violent extremism, new research suggests that it could contribute to the complex process of radicalisation, of lone terrorists in particular, when combined with a further series of psychosocial factors. In this regard, social exclusion has been the most widely studied subject in the literature on lone wolves; with studies demonstrating that more than half of lone terrorists are socially isolated.

Therefore, risk assessment of terrorist radicalisation of the mentally ill could be of particular interest from the perspective of forensic science in evaluating criminal dangerousness; particularly for adopting security measures, and in correctional psychology. The problem is that there are still no agreed guidelines or protocols to assist forensic scientists in this specific activity. To assess the risk of radicalisation of the lone wolf, in the United States, the Global Institute of Forensic Research recently published the Terrorist Radicalisation Assessment Protocol-18 (TRAP-18), which has shown good reliability, but its strengths and limitations as a structured professional judgment instrument for mental health practitioners are still a matter of debate.9

The aim of this study was to examine the predictive validity of TRAP-18 in a sample of patients with severe mental illness in a situation of social exclusion, and with a prison history. We specifically set out to evaluate the capacity of total TRAP-18 scores to predict future extremist acts of violence.

Material and methodsDesignAn observational naturalistic study performed on a group of patients with a severe mental illness (SMI) in a situation of social exclusion, and with a prison history (at least one previous admission in a correctional facility), attended by the Mental Health Street Team of Madrid's “Programme for the Psychiatric Care of the Homeless Mentally Ill”.10,11

The abovementioned programme provides social, health and psychiatric care for all adult homeless people in the municipality of Madrid with a SMI, and who for various reasons are not being monitored by the standard mental health network. We followed the criteria of the Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless (FEANTSA) based on the European typology on homelessness and-housing exclusion (ETHOS) to categorise a person as homeless.12 We used the criteria of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to define SMI.13

SampleThe sample study was selected from a total of 235 patients who had completed the Baseline Assessment Protocol (which is given to all subjects when they are included in the “Psychiatric care programme for the homeless mentally ill”) from June 2014 (when the tool was first implemented within the programme) to June 2017. Those with a history of (at least) one prison sentence were included (the TRAP-18 was completed later on these subjects).

The sample comprised 44 male patients with a mean age of 42.9 years (SD=14.0). Of the total sample, 16 patients (36.4%) were Spanish, 8 (18.2%) were from North Africa, 9 (20.5%) from Sub-Saharan Africa, 7 (15.9%) from Europe (not Spanish), 3 (6.8%) from Asia, and 1 (2.3%) from Central America. Most patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenic spectrum disorder (n=29; 65.9%), 3 (6.8%) had a diagnosis of delusional ideas disorder, 2 (4.5%) affective disorder, 3 (6.8%) personality disorder, 1 (2.3%) organic mental disorder, 4 (9.1%) substance abuse disorder, and 2 (4.5%) personality disorder.

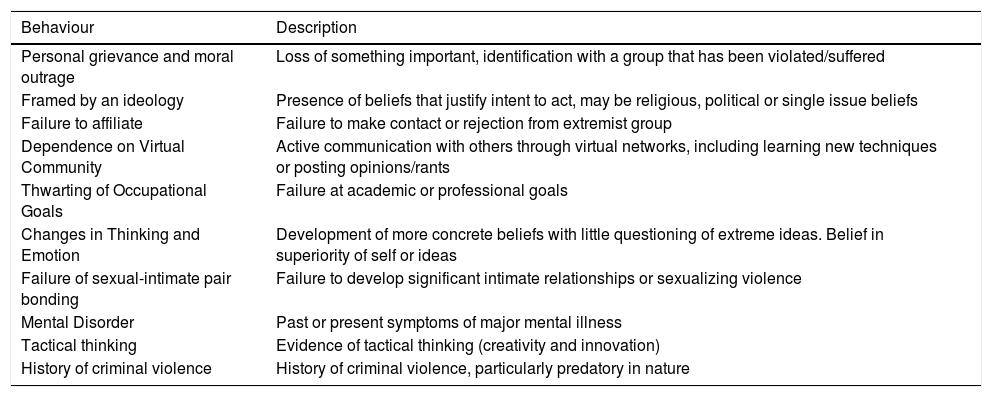

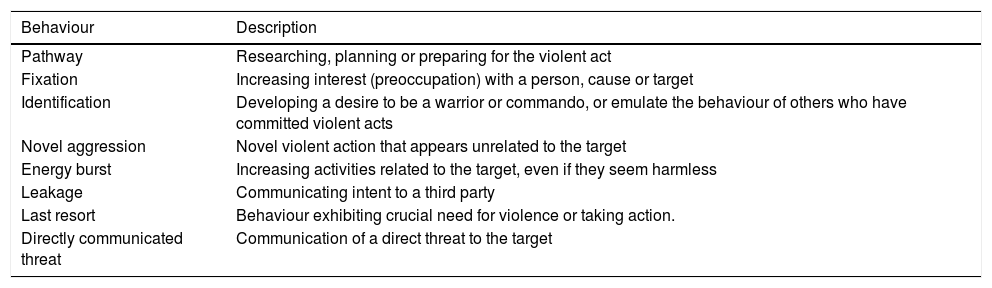

Assessment instrumentThe Terrorist Radicalisation Assessment Protocol-18 (TRAP-18)14 was used to assess the risk of a new act of extremist violence. This protocol examines two broad categories of indicators: (1) warning behaviours and (2) distal characteristics (Tables 1 and 2). The TRAP-18 model identifies 8 proximal behaviours that may be apparent in varying patterns, commonly observed immediately before targeted violence is committed. The presence of these behaviours indicates a warning (which means that the violent act could be imminent) in addition to the warning behaviours (proximal criteria) identified in the literature on terrorism. These distal criteria are commonly seen in individuals with the potential to commit an extremist act, but are not necessarily indicative of those that are about to commit acts of violence. Although in the user manual (version 1.0),14 the authors of TRAP-18 advise that it should not be “scored” when used as an individual risk assessment tool, this study (for research purposes) scores on a scale of 2 points (0 or 1) where 0 indicates that the item is definitely absent and 1 indicates that the item is possibly present; therefore the total score ranges from 0 to 18.

Distal criteria of the TRAP-18.

| Behaviour | Description |

|---|---|

| Personal grievance and moral outrage | Loss of something important, identification with a group that has been violated/suffered |

| Framed by an ideology | Presence of beliefs that justify intent to act, may be religious, political or single issue beliefs |

| Failure to affiliate | Failure to make contact or rejection from extremist group |

| Dependence on Virtual Community | Active communication with others through virtual networks, including learning new techniques or posting opinions/rants |

| Thwarting of Occupational Goals | Failure at academic or professional goals |

| Changes in Thinking and Emotion | Development of more concrete beliefs with little questioning of extreme ideas. Belief in superiority of self or ideas |

| Failure of sexual-intimate pair bonding | Failure to develop significant intimate relationships or sexualizing violence |

| Mental Disorder | Past or present symptoms of major mental illness |

| Tactical thinking | Evidence of tactical thinking (creativity and innovation) |

| History of criminal violence | History of criminal violence, particularly predatory in nature |

Proximal criteria (warning behaviours) of the TRAP-18.

| Behaviour | Description |

|---|---|

| Pathway | Researching, planning or preparing for the violent act |

| Fixation | Increasing interest (preoccupation) with a person, cause or target |

| Identification | Developing a desire to be a warrior or commando, or emulate the behaviour of others who have committed violent acts |

| Novel aggression | Novel violent action that appears unrelated to the target |

| Energy burst | Increasing activities related to the target, even if they seem harmless |

| Leakage | Communicating intent to a third party |

| Last resort | Behaviour exhibiting crucial need for violence or taking action. |

| Directly communicated threat | Communication of a direct threat to the target |

The TRAP-18 was completed retrospectively based on the Baseline Assessment Protocol (which is applied to subjects when they are included in the programme) by a psychiatrist trained in the use of risk assessment tools, and involved in the assessment and follow-up of each patient.

The data (after completing TRAP-18) on new acts of violent extremism were obtained from clinical history reviews by the investigators. The definition of violence by the authors of the HCR-20 violence risk assessment scheme-2015 was used to identify episodes of repeated violence from the patient's clinical history; which include all physical aggression, verbal aggression, violence against property or sexually inappropriate behaviour. The subjects who had committed new acts of violent extremism were recorded in this group of repeated episodes, using the European Union's definition of violent radicalisation.16

The scores of the 44 individuals in each item of the TRAP-18 were recorded on an anonymised database, as well as the total score of each of the subscales, and the total score. The follow-up period started the day after the Baseline Assessment Protocol had been completed, and continued until the time of data collection (June 2018) or until the date that the individual was discharged from the programme (time interval of 1–12 months).

This study was performed with the approval of the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Madrid's Clínico San Carlos, in compliance with all the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki, and Spanish legislation on data protection.

Statistical analysisThe qualitative variables were expressed by their frequency distribution, and the quantitative variables (normally distributed) by their mean±standard deviation (SD).

The Student's t-test (or non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test), and the χ2 test (or Fisher's exact test if more than 25% of the expected values were less than 5) were used for the qualitative variables. The Student's t-test for independent samples was used to examine differences in the total TRAP-18 scores between violent extremists and those who had not committed extremist violence, and the Mann–Whitney test for the significant differences in the subscales of the TRAP-18 (ordinal data).

The predictive validity of the assessment instrument (TRAP-18) was analysed by Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Values of the area under the curve (AUC) of .70 and above are considered moderate, and above .75 good.

The accepted significance level was 5% for all these tests. SPSS version 15.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

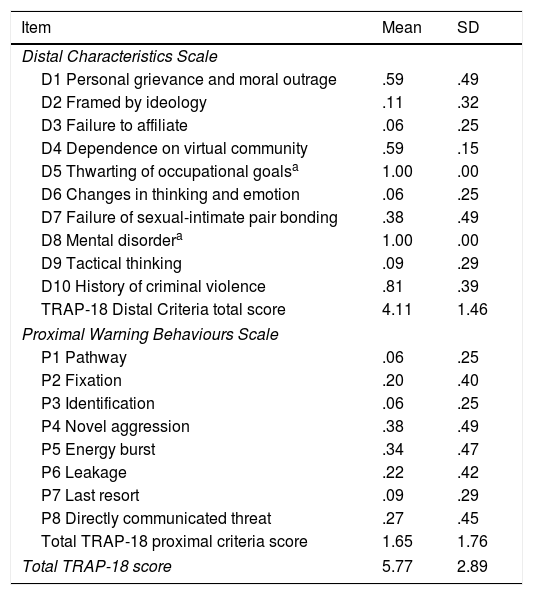

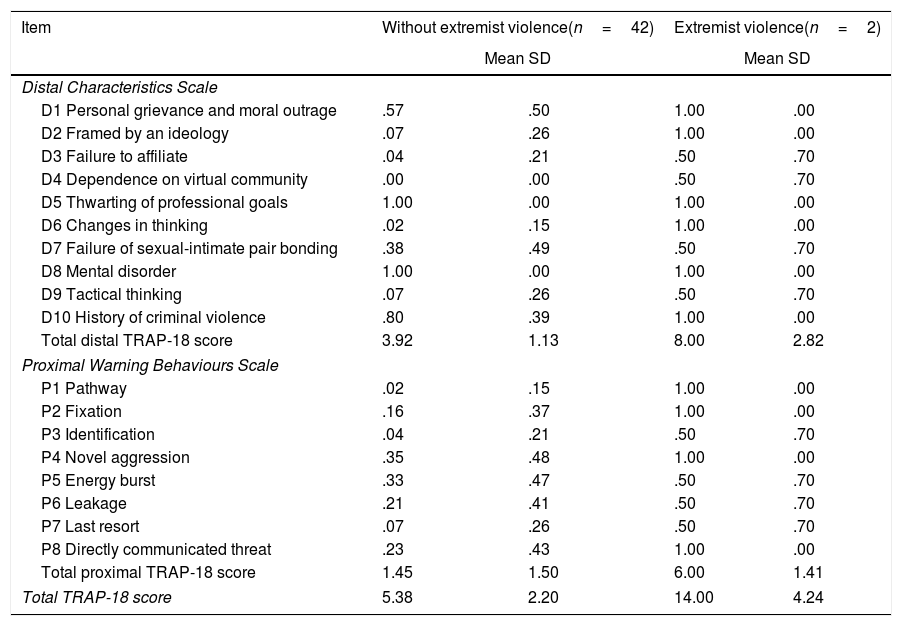

ResultsDescriptive statistics of the TRAP-18 scores and features of the groups with and without extremist violenceTable 3 shows the results per item, subscales, and total score of the TRAP-18.

TRAP-18: mean scores and SD for each individual item, the score of each subscale and total score (n=44).

| Item | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Distal Characteristics Scale | ||

| D1 Personal grievance and moral outrage | .59 | .49 |

| D2 Framed by ideology | .11 | .32 |

| D3 Failure to affiliate | .06 | .25 |

| D4 Dependence on virtual community | .59 | .15 |

| D5 Thwarting of occupational goalsa | 1.00 | .00 |

| D6 Changes in thinking and emotion | .06 | .25 |

| D7 Failure of sexual-intimate pair bonding | .38 | .49 |

| D8 Mental disordera | 1.00 | .00 |

| D9 Tactical thinking | .09 | .29 |

| D10 History of criminal violence | .81 | .39 |

| TRAP-18 Distal Criteria total score | 4.11 | 1.46 |

| Proximal Warning Behaviours Scale | ||

| P1 Pathway | .06 | .25 |

| P2 Fixation | .20 | .40 |

| P3 Identification | .06 | .25 |

| P4 Novel aggression | .38 | .49 |

| P5 Energy burst | .34 | .47 |

| P6 Leakage | .22 | .42 |

| P7 Last resort | .09 | .29 |

| P8 Directly communicated threat | .27 | .45 |

| Total TRAP-18 proximal criteria score | 1.65 | 1.76 |

| Total TRAP-18 score | 5.77 | 2.89 |

SD: standard deviation.

Of the 44 subjects included, 13 patients had committed a further violent act, and 31 had not. And of the 13 recidivists, only 2 had committed a repeat act of violence that was extremist in nature. The independent χ2 test analyses found no significant differences in terms of age (p=.95; χ2=.03), ethnicity (p=.95; χ2=.03) or diagnosis (p=.95; χ2=.03) between the groups.

Table 4 shows the results of the TRAP-18 per group; there is a statistically significant difference in the total score of the TRAP-18 (t(44)=5.22; p<.001) between the groups.

Mean TRAP-18 score for the groups without extremist violence and with extremist violence (n=44).

| Item | Without extremist violence(n=42) | Extremist violence(n=2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean SD | Mean SD | |||

| Distal Characteristics Scale | ||||

| D1 Personal grievance and moral outrage | .57 | .50 | 1.00 | .00 |

| D2 Framed by an ideology | .07 | .26 | 1.00 | .00 |

| D3 Failure to affiliate | .04 | .21 | .50 | .70 |

| D4 Dependence on virtual community | .00 | .00 | .50 | .70 |

| D5 Thwarting of professional goals | 1.00 | .00 | 1.00 | .00 |

| D6 Changes in thinking | .02 | .15 | 1.00 | .00 |

| D7 Failure of sexual-intimate pair bonding | .38 | .49 | .50 | .70 |

| D8 Mental disorder | 1.00 | .00 | 1.00 | .00 |

| D9 Tactical thinking | .07 | .26 | .50 | .70 |

| D10 History of criminal violence | .80 | .39 | 1.00 | .00 |

| Total distal TRAP-18 score | 3.92 | 1.13 | 8.00 | 2.82 |

| Proximal Warning Behaviours Scale | ||||

| P1 Pathway | .02 | .15 | 1.00 | .00 |

| P2 Fixation | .16 | .37 | 1.00 | .00 |

| P3 Identification | .04 | .21 | .50 | .70 |

| P4 Novel aggression | .35 | .48 | 1.00 | .00 |

| P5 Energy burst | .33 | .47 | .50 | .70 |

| P6 Leakage | .21 | .41 | .50 | .70 |

| P7 Last resort | .07 | .26 | .50 | .70 |

| P8 Directly communicated threat | .23 | .43 | 1.00 | .00 |

| Total proximal TRAP-18 score | 1.45 | 1.50 | 6.00 | 1.41 |

| Total TRAP-18 score | 5.38 | 2.20 | 14.00 | 4.24 |

SD: standard deviation.

In order to assess the differences between the group that had committed a new act of violent extremism and the group that had not, the correlational effect sizes were as follows:

In the analysis of the Mann–Whitney test on the two subscales (distal and proximal) of the TRAP-18 it was observed that those who had committed a new act of violent extremism (average range=43.0) differed significantly (p=.004; U=904) and identically in their scores both in the distal subscale (Distal Characteristics Scale), and the proximal subscale (Proximal Warning Behaviour Scale), compared to the group with no violent extremism (average range=21.52).

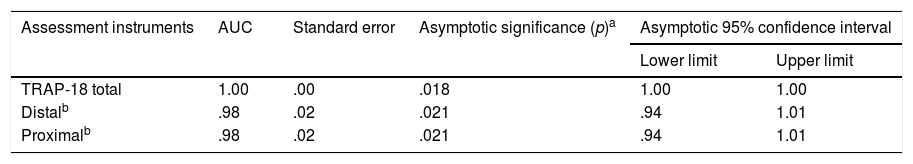

Predictive validity of the TRAP-18: ROC analysisThe results of the ROC analysis are shown in Table 5. The AUC was higher for the total score of the TRAP-18 than for the separate scores of the subscales (distal and proximal) of the TRAP-18. The total score of the TRAP-18 significantly predicted repeat violence extremist in nature (AUC 1.00, p=.018). In addition, the distal subscale of the TRAP-18, and the proximal subscale of the TRAP-18 are also significant separate predictors of future repeated violent acts of an extremist nature (with an AUC .98 and p=.021 for both subscales).

Area under the curve for the total scores and subscales of the TRAP-18.

| Assessment instruments | AUC | Standard error | Asymptotic significance (p)a | Asymptotic 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| TRAP-18 total | 1.00 | .00 | .018 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Distalb | .98 | .02 | .021 | .94 | 1.01 |

| Proximalb | .98 | .02 | .021 | .94 | 1.01 |

AUC: area under the curve.

The principal result of this study is that the Terrorist Radicalisation Assessment Protocol-18 (TRAP-18) is a useful tool for the forensic psychiatric assessment of the risk of terrorist radicalisation of a mentally ill and socially excluded person, as demonstrated by its potential validity in predicting future acts of violent extremism by subjects with a prison history.

This research study is necessary because the limitations of the TRAP-18 as a useful assessment instrument for mental health professionals in general and forensic psychiatry in particular are still being argued.17 Furthermore, the studies that have investigated the phenomenon of terrorist radicalisation using TRAP-18 are not based on samples of mentally ill people. For this reason, it is difficult to compare the results of this study with other reported results.

Although only two patients (of the thirteen repeat offenders) committed a further act of extremist violence, the statistical analyses indicated that there was a significant difference between the groups with and without extremist violence in the total score of the TRAP-18, and in the proximal and distal subscales, and therefore the extremist violence group had significantly higher scores. The AUC analysis also showed that the predictive precision of the total score of the TRAP-18 was superior to that of the proximal and distal subscales (separately) for future acts of extremist violence. Although the score of the proximal and distal subscales were also a significant predictor (AUC .98) of future acts of extremist violence in this sample, the statistics could be biased (since the contrast outcome variable had at least one draw between the positive real condition group, and the negative real condition group).

We found the following in both the patients who went on to commit a new act of extremist violence: a personal grievance and feeling of moral outrage, framing by an extremist ideology, a history of criminal violence (of a predatory nature), the act of violence was planned, fixation with a specific target, a further violent action that appeared unrelated to the target, and directly communicated threats. In relation to personal grievances and moral indignation, it is possible that the specific psychopathology of each of the individuals bore an influence on their feelings of anger and humiliation, blaming others and vicarious identification with a group that has suffered. The type of framing by an ideology (i.e., the presence of beliefs that justify the terrorist's intention to act whether a religious belief system, political philosophy, secular commitment, single issue conflict or an idiosyncrasy)14 should be studied in subsequent research studies, since as Corner and Gil1 argue, those with a single-issue ideology are more typically obsessed with a target that they regard wholly responsible for their grievance. This described behaviour is reflected in specific mental illnesses with intrusive thought processes or delusional ideas that cause fixations on specific targets that the individual consider responsible. The ideology helping (or otherwise) to relieve the symptoms of the mental disorder is a secondary, but important consideration; since according to Meloy and Yakeley18 “an esoteric or nihilistic belief is utilised by the individual to manage the anxiety of a decompensating mind”. Furthermore the presence of items on warning criteria (proximal) suggests that mental health practitioners can play an important role in the prevention of lone acts of terrorism.

Another indirect, yet relevant, finding of this study is the apparent evidence that the patient with a severe mental illness, in a situation of social exclusion and with a prison history has a baseline of greater vulnerability that increases their risk of terrorist radicalisation. This was observed in the study, in that all the subjects of the sample constantly presented several of the items that increase the risk of terrorist radicalisation (such as a mental disorder and thwarting of occupational goals). In relation to mental disorder, it has recently been described that the odds of a lone-actor terrorist having a mental illness are 13 times the odds of a group actor having a mental illness.1 However as Corner and Gill argue,1 the relatively low prevalence in the descriptive statistics, along with the evidence that mental illness is seldom attributed as a direct cause of terrorist violence, compels us to believe that the lone terrorist is essentially motivated by an ideology developed over time, together with other risk factors, not mental illness alone. And in this regard, social exclusion and its consequences (such as thwarting of occupational goals) may play a determining role.

Finally, with regard to the psychiatric diagnosis it is also important to highlight that, although delusional disorder and schizophrenia are most frequently associated with lone wolf terrorism,1 in this study we found no significant differences between the groups without extremist violence and the group with extremist violence (the diagnoses of the two subjects who had displayed extremist violence behaviour were schizophrenia and delusional disorder) possibly due to the high prevalence of both mental illnesses in the entire sample. It is also worth noting that neither ethnicity nor age were significantly different between the groups compared.

ConclusionsForensic psychiatric assessment of the risk of terrorist radicalisation in the mentally ill might be of particular interest in the evaluation of criminal dangerousness, especially in light of recent research studies on so-called lone wolf terrorists, which suggest the need to revisit the subject of mental illness as part of the process through which some individuals become involved in terrorism.

The Terrorist Radicalisation Assessment Protocol (TRAP-18) could be a useful tool for forensic psychiatric assessment of the risk of terrorist radicalisation of the mentally ill.

The collective of extremely socially excluded people with severe mental illness, and a prison history, has a baseline of greater potential risk of terrorist radicalisation as lone wolves. The TRAP-18 shows optimal predictive validity for future acts of extremist violence in this vulnerable population.

LimitationsThese results should be interpreted with great caution because the sample size was small, there is the possibility of retrospective bias that might affect the results, and the TRAP-18 is recommended for use in combination with other tools to ensure greater precision through the use of many methods. It is necessary, therefore, to undertake further larger, prospective research studies.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Fernández García-Andrade R, Serván Rendón-Luna B, Reneses Prieto B, Vidal Martínez V, Medina Téllez de Meneses E, Fernández Rodríguez E. Valoración psiquiátrico-forense del riesgo de radicalización terrorista en el enfermo mental. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2019;45:59–66.