The assessment and management of risk of intimate partner violence against women is a priority in police, legal and forensic contexts. This work analyzes the performance of the last update of the tool included in the VioGén System (VPR4.0).

Material and methodA total of 7147 new intimate partner violence against women complaints were analysed, with a follow-up of 320 days. Recidivism between levels of risk was compared, estimating prediction parameters and the survival curve.

ResultsThe police recidivism was 14.3% (56.5% of it in the first 3 months) and the VPR4.0 anticipated significantly recidivism, serious violence and multi-recidivism (sensitivity 79%; specificity 35%; AUC 0.62; PPV 17%; NPV 91%). The greater the risk, the less was the time until recidivism.

ConclusionsThe VPR4.0 is useful to predict and manage risk, being more accurate in the detection of recidivists (sensitivity), but with more success in cases labelled as low risk (NPV).

La evaluación y gestión del riesgo de violencia contra la mujer en la pareja es prioritario en contextos policiales, jurídicos y forenses. El presente trabajo analiza el funcionamiento de la última actualización de la herramienta incluida dentro del Sistema VioGén (VPR4.0).

Material y métodoSe analizaron 7.147 nuevas denuncias por violencia contra la mujer en la pareja, con un seguimiento de 320 días. Se comparó la reincidencia entre niveles de riesgo, calculando parámetros de predicción y la curva de supervivencia.

ResultadosLa reincidencia policial fue del 14,3% (el 56,5% en los 3 primeros meses) y el VPR4.0 anticipó la reincidencia, la violencia grave y la multirreincidencia significativamente (sensibilidad 79%; especificidad 35%; AUC 0,62; VPP 17%; VPN 91%). A mayor riesgo, menor fue el tiempo hasta la reincidencia.

ConclusionesEl VPR4.0 resulta útil para predecir y gestionar el riesgo, más preciso detectando reincidentes (sensibilidad), pero con más aciertos en casos de bajo riesgo (VPN).

Risk assessment of intimate partner violence is a priority in police, legal and forensic contexts. Training in the use of protocols and their revision is constantly required. Thanks to the impetus of L. O. 1/2004, not only have international protocols such as SARA, B-SAFER and DA been adapted in Spain, but we have created our own tools for use by the police (the Police Gender Violence Risk Assessment [VPR] and the EPV-R), and the social and health services (RVD-Bcn). These tools have been created to help different professionals in decision-making to protect victims of intimate partner violence, principally by linking risk levels with specific protection measures.1

The VioGén System2 includes, among other features, police assessment of the risk of violence against women/intimate or ex partners using VPR forms, and the police risk assessment (VPER), that classify cases into 5 levels of risk of recidivism (unappreciable, low, medium, high or extreme). In recent years the protocols have been subjected to various reviews and analyses, such as their use in predicting recidivism at 3 and 6 months with version 3.13 or reviewing risk factors that differentiate recidivists from non-recidivists.4 In parallel, analyses have also been performed of the satisfaction of victims with the process,5 or the opinion of the officers on the available risk management measures.6

The Autonomous Basque Police (Ertzaintza), and the Autonomous Catalan Police (Mossos d’Esquadra) were not involved in the application of this protocol. For their part, the Ertzaintza commissioned the creation of their own instrument to differentiate different severe violence groups,7 and adjust police protection measures to different levels of risk. The result was the EPV-R,8 which is currently used by the Autonomous Basque Police and local police forces of this autonomous region, and which due to its simplicity and usefulness in assessing risk levels using numerical criteria (actuarial method), has also extended to some Legal and Forensic Science Institutes.9 Various methods have recently been analysed experimentally to respond to missing values, such as the item response theory.10

Risk assessment has various objectives, procedures and methodologies. The tools for police risk assessment currently used in Spain use the method referred to as adjusted actuarial assessment.1 On the one hand, the tools work with a mathematic algorithm and cut-off points outside the opinion of the professional (the result is objective and derives from the sum of factors). However, on the other hand, the system allows the professional to modify the result according to their agreement with it, the main idea being that, if there is any doubt or the impression of a higher risk than that obtained mathematically, the professional can recommend superior management to that indicated by the tool.

With regard to the performance of the tools, a series of indicators are routinely used in assessing their usefulness to provide information on parameters of discrimination and calibration1,11: (a) sensitivity (proportion of recidivist cases labelled as high risk); (b) specificity (proportion of non-recidivist cases labelled as low risk); (c) positive predictive value (PPV, proportion of individuals classified as at high risk of recidivism); (d) negative predictive value (NPV, proportion of individuals classified as at low risk of non-recidivism); (e) area under the curve (likelihood of recidivist scoring more than a non-recidivist); (f) odds ratio (likelihood of an event occurring when a variable is present); (g) relative risk (likelihood of an event occurring in cases with a variable compared to cases without the variable). These indicators, routinely used in research in this area, constitute one of the criteria to be used by professionals in understanding the usefulness of a specific tool.

The aim of this paper was to test the performance parameters obtained in implementing the fourth version of the VPR to check its functioning one year after updating the protocol. The aim was to analyse its capacity to distinguish recidivists and calibrate risk levels to provide indicators of usefulness to potential users of the protocol or risk assessment target groups deriving from their use. The ultimate aim of all of the above being to update and improve the VPR4.0 form based on the new results.

Material and methodA prospective, multi-centre study was designed, including and following up all cases assessed by the security forces using the Viogén System (National Police, Guardia Civil, Regional Police of Navarre, and the local police forces of certain municipalities) between 1 October and 30 November, 2016.

ProtocolThe VPR protocol has been implemented since 2007, and is used throughout almost all of Spain with around 400,000 annual assessments.2 Initial risk is estimated using the VPR form to classify cases, and assign police protection measures according to risk (approximately 50,000 annually). The VPR is completed by the police officer when a complaint is presented for the first time, from information supplied by the various people involved: victim, aggressor, witnesses, technicians, etc. It can also be filled in at judicial request or requested by the Prosecution Service (cases of transferral to the court and the Prosecution Service of both the initial assessment and subsequent assessments that involve an amendment to higher or lower severity from the last reported risk assessment, together with a report on the principal risk indicators assessed). A number of police protection measures have been recommended for each level of risk. Between 2007 and 2010, the VPR required 3 updates, and a further review was started in 2014, which was addressed using recidivism studies to assess new indicators, and the VPR4.0 version was implemented in 2016.4

After applying the VPR, police officers use the VPER form for risk monitoring or management (approximately 350,000 per year), which includes indicators of risk and protection that are sensitive to new risk scenarios generated after the allegation. During follow-up of the case, to keep the risk assessment and victim protection updated, specialist police units complete the VPER4.0 (in use since 2016), that has 2 forms: one called VPER-S (without incident), to be completed within fixed times (extreme level, within 72h; high level, within 7 days; medium level, after 30 days; and low level, every 60 days); and VPER-C (with incident), to be completed when a new episode of violence occurs or knowledge of a relevant circumstance.

ProcedureAll cases discharged between October and November 2016. A total of 7147 valid cases were obtained (57.6% corresponding to the National Police; 38.8% to the Guardia Civil; 3% to local police forces; and .6% to the regional police force of Navarre). These cases were then followed up between October 2016 and August 2017 (320 days) to analyse the prediction and functioning of the protocols. In order to determine recidivism, the VPER-C forms that were completed due to a new allegation of an offence other than that originating registration of the case, provided that they included an indicator relating to a violent episode: physical, sexual, psychological violence or threats, including breaches of sentences. A case with more than one VPER-C was considered multi-recidivist. The severity variable of recidivism was determined by examining that indicated by the officers for the 4 first factors of the first VPER-C of each case, and considered present when “severe” or “very severe” level intensities were highlighted in one of the indicators of physical, sexual, psychological violence or threat.

Statistical analysisThe dependent variables were recidivism, multi-recidivism, severity of violence, and the time from the initial risk assessment (VPR4.0) until the recidivism was recorded (event) or the end of follow-up at 320 days. The risk variable, measured with VPR4.0, was dichotomised as “non-appreciable/low”, and “medium/high/extreme” to then analyse the test theory item discrimination estimators (odds ratio, sensitivity and specificity), and calibration (PPV and NPV) using 2×2 tables (yes/no prediction vs yes/no result). The analysis of the area under the curve was performed with the VPR score, and dichotomous recidivism as a predictable variable along with severity, and multi-recidivism. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to analyse survival (time until recidivism).

ResultsRecidivismFollow-up of the 7147 cases over 10 and a half months (when, for technical reasons, it was possible to extract data from the VioGén System) enabled a recidivism rate of 14.3% to be confirmed (1020 new allegations). Recidivism at 3 months was 8%; 11.5% accumulated at 6 months; 13.7% at 9 months, and on the date of closure, accumulated recidivism was 14.3%. At 3 months 56.5% of the total recidivism had taken place, and 81% at 6 months.

Of the cases, 41.5% (n=424) were multi-recidivists and 69.6% of all these cases were recorded during the first quarter (21.8% at 6 months; 7.3% at 9 months, and 1.8% at 10 months). Of the total recidivists, it was found that for 228 (22.5%) the officers had highlighted the options “severe” or “very severe” for one of the three violence indicators or for the threat indicator of the first VPER-C. On comparing severe and non-severe recidivists, those considered severe in the first VPER-C reoffended significantly more (39.5%) than those considered less severe (4.8%; χ2=474.7; p=.000). These cases of greater severity also tend to have been reported during the first 3 months (55.7%).

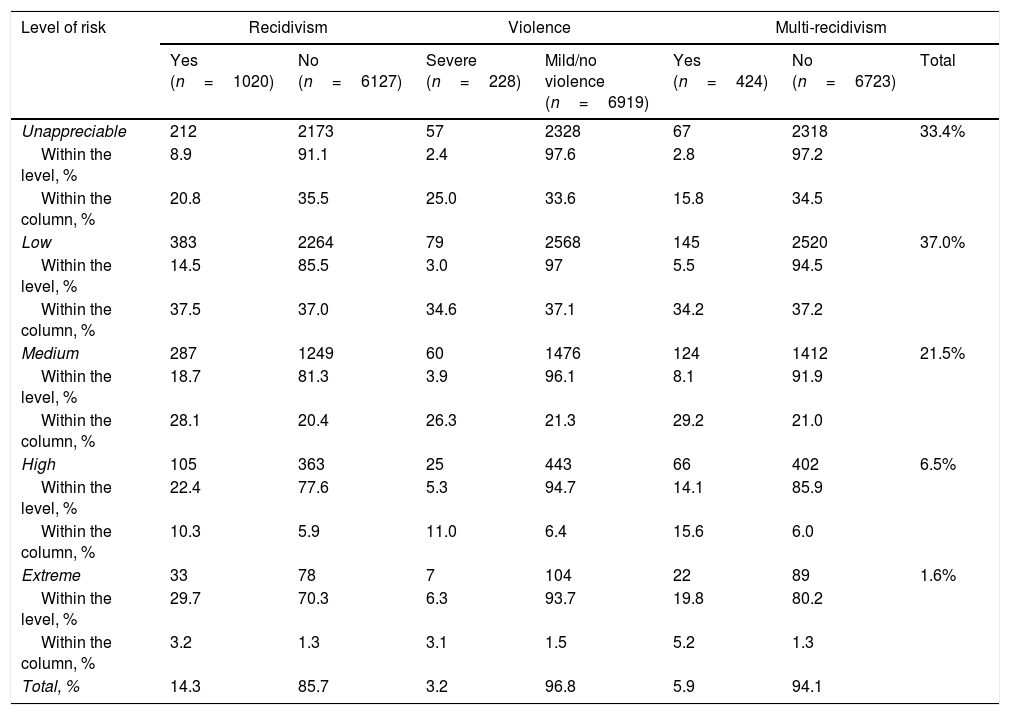

Prediction of recidivism, severity and multi-recidivismRecidivism. With regard to recidivism, according to the initial risk classification made with the VPR4.0, as shown in Table 1, the percentage of recidivism within each risk level progressively and significantly increased from lower to higher risk (χ2=128.192; p=.000). There was a growing linear trend in this case: the higher the level of risk, the higher the rate of recidivism. Considering the recidivist cases alone (column percentage in the table), due to the lower representativeness of the highest risk levels, the percentage of recidivism was higher among the lower (and more numerous) levels than among the higher levels.

Prediction of recidivism, severe violence and multi-recidivism.

| Level of risk | Recidivism | Violence | Multi-recidivism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=1020) | No (n=6127) | Severe (n=228) | Mild/no violence (n=6919) | Yes (n=424) | No (n=6723) | Total | |

| Unappreciable | 212 | 2173 | 57 | 2328 | 67 | 2318 | 33.4% |

| Within the level, % | 8.9 | 91.1 | 2.4 | 97.6 | 2.8 | 97.2 | |

| Within the column, % | 20.8 | 35.5 | 25.0 | 33.6 | 15.8 | 34.5 | |

| Low | 383 | 2264 | 79 | 2568 | 145 | 2520 | 37.0% |

| Within the level, % | 14.5 | 85.5 | 3.0 | 97 | 5.5 | 94.5 | |

| Within the column, % | 37.5 | 37.0 | 34.6 | 37.1 | 34.2 | 37.2 | |

| Medium | 287 | 1249 | 60 | 1476 | 124 | 1412 | 21.5% |

| Within the level, % | 18.7 | 81.3 | 3.9 | 96.1 | 8.1 | 91.9 | |

| Within the column, % | 28.1 | 20.4 | 26.3 | 21.3 | 29.2 | 21.0 | |

| High | 105 | 363 | 25 | 443 | 66 | 402 | 6.5% |

| Within the level, % | 22.4 | 77.6 | 5.3 | 94.7 | 14.1 | 85.9 | |

| Within the column, % | 10.3 | 5.9 | 11.0 | 6.4 | 15.6 | 6.0 | |

| Extreme | 33 | 78 | 7 | 104 | 22 | 89 | 1.6% |

| Within the level, % | 29.7 | 70.3 | 6.3 | 93.7 | 19.8 | 80.2 | |

| Within the column, % | 3.2 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 5.2 | 1.3 | |

| Total, % | 14.3 | 85.7 | 3.2 | 96.8 | 5.9 | 94.1 | |

Survival analysis for recidivism in periods of 15 days showed that 51% of recidivism occurred in the first 60 days (49% survival) and, as already mentioned, at 90 days 62% had reoffended (38% survival). On the other hand, with regard to survival in terms of level of risk, the Kaplan–Meier method with the Log Rank test (Mantel–Cox) showed a significant relationship between time until recidivism and level of risk. Thus, the shorter the time until recidivism, the greater the level of risk. The mean number of days until recurrence was 100 in the group labelled as low risk, 87 in the medium risk group, 80 in the high risk group, and 56 in the extreme risk group.

Severity. The level of (non fatal) severity also linearly correlated with the level of risk, both growing at the same time (χ2=17.569; p=.000). Within each level of risk, the percentage of severe cases progressed by 2.4% in the unappreciable levels to 3% in the low levels, 3.9% in the medium levels, 5.5% in the high levels, and 6.3% in the extreme levels, with statistically significant differences (χ2=18.364; p=.001).

Multi-recidivism. The VPR4.0 classification by level of risk had the same linear functioning for predicting multi-recidivism, and this was significantly higher as the level of risk increased (χ2=149.6; p=.000).

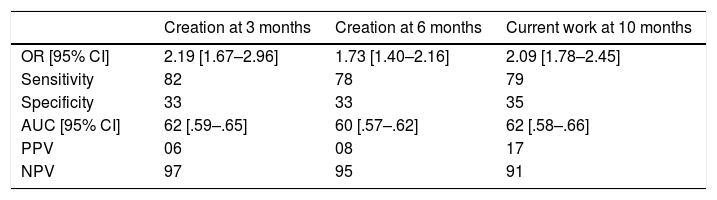

Performance of the VPR4.0 protocolThe performance indicators of the VPR4.0 obtained in the new sample are compared with those obtained with the sample for creating the form at 3 and 6 months in Table 2. All the indicators obtained in this task (with follow-up at 10 months) are similar to those obtained at 3 and 6 months in the creation study, except the PPV (proportion of cases classified with some type of risk – low, medium, high or extreme – and who reoffended), which was higher in the new sample, and the NPV (proportion of cases classified as unappreciable risk and who did not reoffend), which was rather worse.

Performance parameters of the VPR4.0 compared with the creation sample.

| Creation at 3 months | Creation at 6 months | Current work at 10 months | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | 2.19 [1.67–2.96] | 1.73 [1.40–2.16] | 2.09 [1.78–2.45] |

| Sensitivity | 82 | 78 | 79 |

| Specificity | 33 | 33 | 35 |

| AUC [95% CI] | 62 [.59–.65] | 60 [.57–.62] | 62 [.58–.66] |

| PPV | 06 | 08 | 17 |

| NPV | 97 | 95 | 91 |

AUC: area under the curve; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval OR: odds ratio; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value.

As we explained in the introduction, the actuarial systems for predicting the risk of intimate partner violence used by the police in Spain follow the method referred to as adjusted actuarial assessment. On analysing the concordance between the level of risk estimated by VPR4.0 and the professional judgement of the officer a coincidence of 90.7% was obtained.

Influence of risk managementBecause all police assessments of risk involve applying victim protection measures (for risk management), in order to determine the impact of these protection measures on recidivism an analogous control group is required (at risk, but without protection) that is ethically plausible. To that end, the cases in the sample with an initial risk assessment of any level that, for different reasons, were inactivated at least one month from discharge (and therefore did not receive any police protection), and those that were reactivated more than 3 months later due to a new allegation were chosen. This methodology enabled a group of 276 cases to be selected for which a risk other than unappreciable had been observed in 194. If the police protection measures have any effect in preventing and reducing recidivism, it is worth positing that in this small group at risk, but without protection, a higher rate of recidivism should be recorded than in the corresponding risk levels of the group with protection. The differences were statistically significant (χ2=96.941; p=.000), resulting in a higher recidivism rate in the cases that were inactivated during this comparative period. To be specific, in the 194 inactivated cases at risk a recidivism rate of 38.7% was recorded, compare to 13.6% of the remaining cases.

DiscussionThe objective of this research study was to analyse the consistency (stability of functioning and its predictive capacity in different time periods) of the latest update of the VPR protocol, and thus provide a description of its functioning, strengths and weaknesses in a sample of 7147 cases that were followed up over 10 months.

Of the cases, 14.3% were considered recidivist by the police in the period of 10 months (56.3% of which reoffended in the first 3 months). Of the recidivist cases, 22.5% were considered severe, and 41.5% multi-recidivist. In these 3 aspects an association was found with time, most of the cases being recorded in the first months of follow-up, and the most severe took less time to reoffend. This aspect has already been highlighted in previous studies,12,13 which is interesting data indicating that the greatest efforts should be invested in risk prevention and management at a time close to the risk assessment.

With regard to prediction, the recidivism rate increased linearly, and in a statistically significant way along with the level of risk. This finding is an indicator of the predictive capacity of the VPR4.0. In essence, greater recidivism, severity and multi-recidivism is confirmed at the highest levels of risk. But it is also true that at the unappreciable, and low levels of risk recidivism rates of 8.9% and 14.5% were recorded respectively, and that 58% of the recidivist cases were cases assessed with these levels of risk. The latter proportion was influenced by the greater number of cases with these levels of risk in the total sample, but in any case would also show a possible margin for improvement of the tool. The little recidivism that appears at the 2 lowest levels of risk indicates a low rate of false negatives, which is of great importance in police risk assessment, which allows a high rate of false positives, focussing resources on the highest levels of risk, where cases of greater severity are recorded.

The parameters of performance, similar to those obtained in the creation of the instrument, are close to the mean values obtained using other tools.1 618 with the DA; .63 with the SARA; .67 with the ODARA, and. 69 with the EPV-R. It is worth highlighting that the most rigorous standards, conceived for more stable and secure disciplines than the study of violence (physical issues, for example), consider these values poor, whereas in the area of assessing the risk of violence, from .64 the value is considered medium, and from .71 it can be considered high.14 The predictive capacity of the VPR, unlike the VPER, is difficult to better, largely due to the fact that officers often have to make rapid assessments with little information, which is in practice is limiting. We should remember also that a limitation linked to daily practice in contexts of police risk assessment is that the different levels of risk (except the unappreciable risk in the case of the VioGén System) are accompanied by the management measures that are considered appropriate. This implies that it is expected and desired that the prediction of the tool is not realised due to the measures taken and that, therefore, the predictive capacity of the tools might not be those desired in other disciplines or for other more experimental contexts (without risk management). When a control group with no protection measures could be isolated, it was confirmed that recidivism was more than double than when this risk was managed.

The tool shows better data in detecting recidivism (sensitivity of 79%) than non-recidivism (specificity of 35%) but, on the other hand, it proves more precise when the cases are labelled as low risk (NPV .91) than when they are labelled as high risk (PPV .17). A parallel reading highlights that the recidivist cases with the highest levels of risk, despite the risk management undertaken, and although the incidence is not very high (compared with the non-recidivist cases), are subjects that are very resistant to the protection measures. Reviewing and reflecting on the legal and criminal relevance of the indicators of how these tools15 function would be summed up in our specific case by the following questions: “labelling a subject as high risk, what is the likelihood of their reoffending?” (We should focus on the PPV of 17%); or “labelling the subject as of unappreciable risk, what is the likelihood of their not reoffending?” (We should focus on the NPV of 91%).

To conclude, the results allow us to claim that the VPR4.0 shows consistent performance parameters compared to those of its creation, and that it is able to predict the risk of recidivism, severe violence and multi-recidivism, with a relationship that is also significant with the time until the event according to the level of risk. The results of this study regarding risk management measures (such as police protection measures) managing to reduce recidivism almost by half reinforce both the usefulness of the tools, and that of the risk management system, both of which contribute to reducing violence. This can be used to conform to the current national and international legal mandates to eliminate or eradicate violence against women, for which the benchmark in Spain is the State Pact against Gender-based Violence (Royal Decree 9/2018). Here we must remember that some of the measures of this Pact concern the legal momentum towards forensic risk assessment, which is currently occasionally undertaken. Therefore, we consider it interesting that forensic experts can have police assessments at their disposal as screening, via the VioGén System, and that the cases that the police consider high or extreme risk can be immediately or urgently assessed by the Integral Forensic Assessment Units created under L. O. 1/2004, and thus help in prioritising their work, which will benefit victims.

Throughout this paper we have referred to the prediction of severe or very severe recidivism, but we must stress that fatal violence has not been studied. Although intimate partner homicide usually attracts political, social, and in particular, media attention, it is a type of violence that is very difficult to predict because of its low prevalence, in the order of .24 per 100,000 women in Spain, accounting for .04% of previously reported cases. In fact, even severe recidivism only reached a prevalence of 3.2% in this study. The difficulty in predicting homicide is also due to the fact that, often, fatal intimate partner violence is not a mere continuation or escalation of previous violence. Although it can share some indicators with recidivism in cases that have been reported previously, it also responds to different factors or indicators.16 The most recent research study on intimate partner homicide in Spain already highlights the different profiles in this group, and the difficulties in anticipating what will arise from it.17–19

In conclusion, future research studies should focus on the improvement not only of the properties of the tools, but also on the appropriateness of the risk management measures.20 With regard to improving the tools, this study enabled data to be compiled that will help to perfect the police risk assessment forms to form a new version (5.0). And, in combination with other studies on fatal violence, we believe that it could even include indicators that help in some way to anticipate homicide in previously reported cases.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: López-Ossorio JJ, Loinaz I, González-Álvarez JL. Protocolo para la valoración policial del riesgo de violencia de género (VPR4.0): revisión de su funcionamiento. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2019;45:52–58.