To identify a set of indicators to monitor the quality of care for patients with major depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder.

MethodsA group of 10 experts selected the most automatically applicable indicators from a total of 98 identified in a previous study. Five online sessions and 5 discussion meetings were performed to select the indicators that met theoretical feasibility criteria automatically. Subsequently, feasibility was tested in a pilot study conducted in two hospitals of the Spanish Health Service.

ResultsAfter evaluating its measurement possibilities in the Spanish Health Service, and the fulfillment of all the quality premises defined, 16 indicators were selected. Three were indicators of major depression, 5 of schizophrenia, 3 of bipolar disorder, and 5 indicators common to all three pathologies. They included measures related to patient safety, maintenance and follow-up of treatment, therapeutic adherence, and adequacy of hospital admissions. After the pilot study, 5 indicators demonstrated potential in the automatic generation of results, with 3 of them related to treatments (clozapine in schizophrenia, lithium for bipolar disorder, and valproate in women of childbearing age).

ConclusionsIndicators support the monitoring of the quality of treatment of patients with major depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder. Based on this proposal, each care setting can draw up a balanced scorecard adjusted to its priorities and care objectives, which will allow for comparison between centers.

Quality health care is a goal for health professionals, who, inherently, seek excellence in their work. An increased focus on improving the quality of health care led to the development of tools to evaluate its efficacy, which has since been incorporated as a fundamental aspect of daily practice. This step toward measurement revolutionized the concept of quality control, paving the way for the concept of quality assurance. Subsequently, we have progressed toward systems of total quality.1 Among the different forms of evaluating the quality of health care, the use of indicators is one of the most widely accepted.2,3

Indicators are measurement tools that serve to evaluate (measure) a criterion related to quality in health care provision, which quantitatively demonstrates the level of quality of the team or the service. When these measurements are used at planned intervals, this is known as a monitoring system, in which the indicator becomes a basic unit. Individually, each indicator provides concrete information that refers to one specific aspect of health care provision; however, in order to obtain enough information to identify the level of quality of a health care service, a selected group of indicators must be developed. The overarching aim of the indicators is to identify situations in which there can be a potential improvement, or rather, defects in the provision of health care. In addition, they may provide information as a warning signal (i.e., alerting us to an urgent matter or danger which must be attended to).2,3

To date, two uses of indicators have been described: monitoring health care provision and performing audits. There are various examples of the former. Canada and Denmark have designed a monitoring system for the provision of health care for patients with schizophrenia4,5 and the STABLE project has defined health care standards for bipolar disorder.6 In terms of audits, in Holland, the following six quality indicators were identified according to their order of importance: treatment plan, care program, measure of the treatment results, involvement of patients and relatives in the treatment, drug therapy, and responsibility of the administration.2

Mental health quality indicators are divided into indicators of “process” and indicators of “results”. In a recent review, up to 727 indicators were detected, of which the majority (75%) were indicators of process.3 Given the extent of these indicators, it seems essential to identify the most relevant, especially those that are most applicable in health care systems.

Until relatively recently, the number of indicators used to monitor and improve health care provision for mental health conditions has been very limited.7 In one review study, 94 quality indicators in mental health were detected.3 In Spain, in 2018, our group defined 70 indicators of major depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. We sought to ensure that they were validated by expert professionals in the field, that they were sensitive enough to detect changes, and that they were applicable.8

Using the previous 2018 study as a theoretical foundation, the objective of this study was to identify a set of basic indicators that would allow for the automatic monitoring of health care provision for major depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder and facilitate the implementation of continuous improvement strategies in the mental health care network in Spain.8

MethodsStudy designThe study comprised three phases. In the first phase, a panel of experts from the Spanish Society of Psychiatry identified a set of indicators based on guidelines and scientific evidence.8,9 The second phase focused on selecting the most relevant indicators. In the third phase, a focus group of mental health specialists sought to simplify the process, by mutual agreement, to make it more pragmatic and to reduce the number of quality health care indicators for major depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. The selected indicators were evaluated in two large hospitals of the Spanish Health Service, where it was verified that they could be applied automatically.

The third phase of the study, described in this article, comprised the following parts: (1) project planning and formation of the focus group; (2) preparation of a document with the initial proposal for criteria/indicators; (3) successive online sessions to select the criteria that would be used to design the indicators; (4) preparation of a document with the design of the indicators; (5) revision, modification, and agreement of the indicators; and (6) retrieval of the indicators from the information systems of the health care administration units in the participating hospitals.

ParticipantsThe following groups participated in the study: coordinators, a focus group, and a technical team. There were two coordinators, one focused on clinical aspects and the other on methodological aspects. The focus group was composed of nine psychiatrists with significant prestige within the field of psychiatry and extensive experience in analyzing pathologies, and one quality of care specialist, who acted as the technical coordinator. The aim of the focus group was to review, modify and agree on the quality indicators, as well as analyze their automatic feasibility.

Selection of criteria and design of indicatorsIndicators were defined as a particular (numeric) form in which a criterion is measured or evaluated; a criterion was defined as a condition that must be fulfilled during the provision of care in order for it to be considered of quality; standard was defined as the degree of fulfillment required of a criterion of quality.

The starting point for this study (Phase 1) was a document called “Quality Criteria in Psychiatry: Schizophrenia, Depression and Bipolar Disorder,” published in 2016 by the Spanish Society of Psychiatry, the Spanish Society of Biological Psychiatry, the Spanish Foundation of Psychiatry and Mental Health, and the Spanish Society of Health Quality.9 This document contained 98 criteria/indicators of quality focused on the three most significant pathologies in Mental Health Care, of which 70 were considered essential according to the experts’ opinion.8 In Phase 2, of these 70 essential indicators, the group of experts prioritized 44, which were distributed as follows: 7 on major depression, 13 on schizophrenia, 11 on bipolar disorder, and 13 applicable to all three pathologies.8 Following this, the 44 indicators were discussed in the focus group which selected 17 criteria according to the actual feasibility tested in the information systems of the pilot hospitals (Phase 3). This process took place during five consecutive online sessions between 2019 and 2020. On the basis of these criteria, in 2021 the Avedis Donabedian University Institute prepared another document including the selected 17 indicators which was subsequently distributed to the nine members of the focus group for their individual revision. Any proposed modification was implemented and five new online sessions took place to revise and agree on the 17 indicators. These sessions, in turn, resulted in additional modifications (Fig. 1).

The selected indicators were grouped by similarity of quality criteria. The focus group created a profile for each of the indicators with the following fields: justification (usefulness of the indicator as a measure of quality), strength of the recommendation (level of evidence), formula for the calculation, explanation/definition of terms, population (clear description of the unit of study), resource (care resource in which the indicator can be measured: inpatient and/or outpatient), type of indicator (structure, process or result), source of information, standard (desired level of performance of the indicator), notes, and up-to-date bibliography.

Pilot studyOnce an agreement was reached in the final version of the indicators, a pilot study was conducted to verify their feasibility, particularly in terms of their automatic generation, which could result in a reduction in the amount of measurement work required to obtain the results of the indicators.

Bellvitge University Hospital and Álava University Hospital participated voluntarily in this phase of the project. These hospitals were chosen as they had access to the professional profile required to take part in the project, namely database management professionals and information technology specialists. Each hospital received a version of the indicators that included the following specific components needed to carry out the measurement: formula, population (with the corresponding ICD-10 diagnostic codes), and the exclusion criteria of each indicator. Following the evaluation, a selection of indicators that could be generated automatically in their hospitals was obtained.

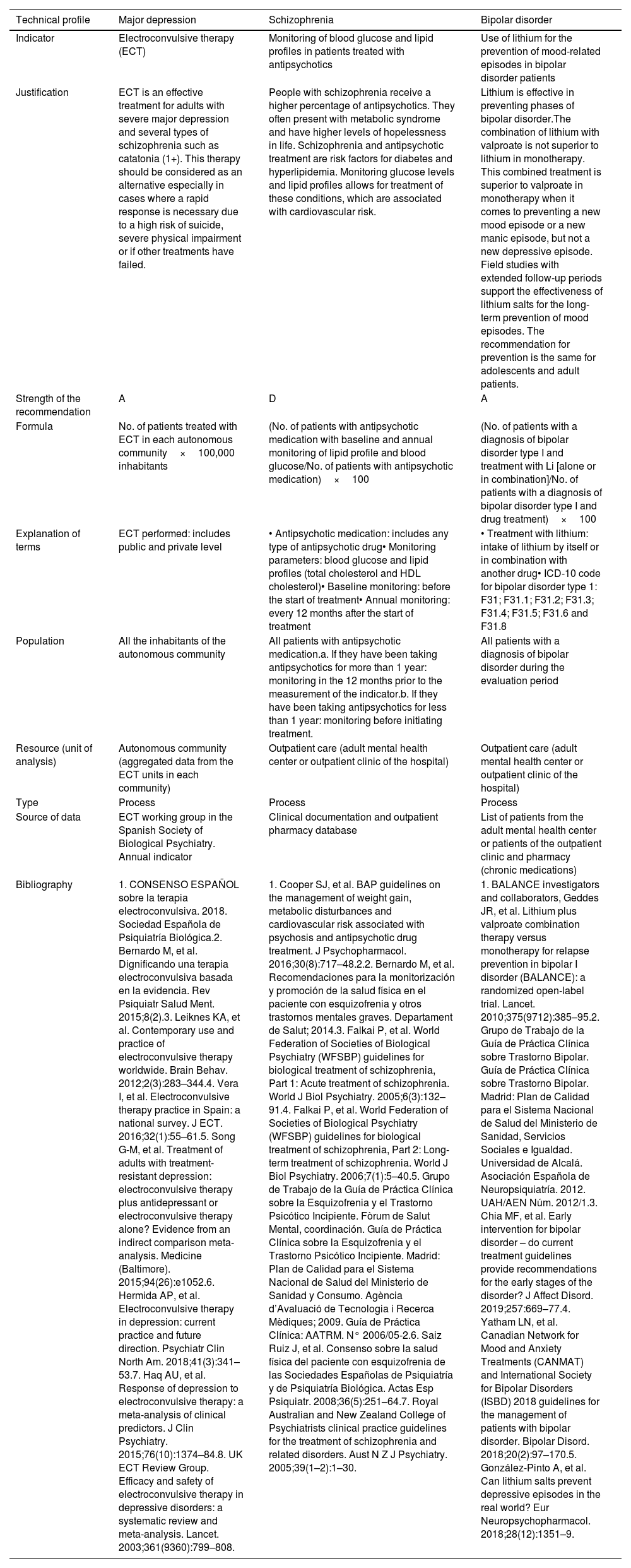

ResultsOf the 17 indicators selected, the working group agreed to eliminate one (“Treatment of schizophrenia with second-generation antipsychotics”), since its applicability was questioned by a number of members of the focus group. Consequently, 16 indicators remained: 3 indicators specific to major depression, 5 indicators specific to schizophrenia, 3 indicators specific to bipolar disorder, and 5 indicators that applied to all three pathologies. Table 1 shows the selected indicators along with their standard, or desired level of performance, and Table 2 shows an example of an indicator's descriptive profile for each of the three pathologies: major depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. The Appendix shows the complete profiles of the 16 selected indicators.

Selected quality indicators.

| Level of care applied(outpatient or inpatient) | Standard | |

|---|---|---|

| Indicators of major depression | ||

| 1. Electroconvulsive therapy | Both | Unavailable |

| 2. Duration of the treatment with depression medication for the treatment of depression ≤9 months | Outpatient | ≤30% |

| 3. Follow-up with patients with major depression | Outpatient | >60% |

| Indicators of schizophrenia | ||

| 4. Treatment of schizophrenia with clozapine | Inpatient | >10% |

| 5. Continuation of drug therapy during the stable phase and stabilization phase after a first psychotic episode | Outpatient | 90% |

| 6. Periodic monitoring of weight and body mass index | Outpatient | 95% |

| 7. Monitoring of blood glucose and lipid profiles in patients treated with antipsychotics | Outpatient | 95% |

| 8. Adherence to outpatient treatment in patients with schizophrenia and treatment with injected extended release antipsychotics | Outpatient | ≤25% |

| Indicators of bipolar disorder | ||

| 9. Use of lithium for the prevention of mood-related episodes in bipolar disorder patients | Inpatient | 70% |

| 10. Use of valproate in women of childbearing age | Both | 2% |

| 11. Suspension of treatment with depression medication during a manic phase | Both | 95% |

| Indicators applicable to all three conditions | ||

| 12. Outpatient care visit after release from the emergency room with a diagnosis of “suicidal behavior” in major depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder | Outpatient | 70% |

| 13. Early follow-up after the first episode of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder | Outpatient | 80% |

| 14. Physical restraining of patients with major depression, schizophrenia or bipolar disorder | Inpatient | ≤5% |

| 15. Patients with major depression or schizophrenia with more than three medications prescribed | Outpatient | ≤30% (adult)≤50% (child) |

| 16. Hospital readmissions at 30 days in major depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder | Inpatient | 7% |

Indicators that may generate results automatically are in bold.

Example of descriptive profile of indicators.

| Technical profile | Major depression | Schizophrenia | Bipolar disorder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) | Monitoring of blood glucose and lipid profiles in patients treated with antipsychotics | Use of lithium for the prevention of mood-related episodes in bipolar disorder patients |

| Justification | ECT is an effective treatment for adults with severe major depression and several types of schizophrenia such as catatonia (1+). This therapy should be considered as an alternative especially in cases where a rapid response is necessary due to a high risk of suicide, severe physical impairment or if other treatments have failed. | People with schizophrenia receive a higher percentage of antipsychotics. They often present with metabolic syndrome and have higher levels of hopelessness in life. Schizophrenia and antipsychotic treatment are risk factors for diabetes and hyperlipidemia. Monitoring glucose levels and lipid profiles allows for treatment of these conditions, which are associated with cardiovascular risk. | Lithium is effective in preventing phases of bipolar disorder.The combination of lithium with valproate is not superior to lithium in monotherapy. This combined treatment is superior to valproate in monotherapy when it comes to preventing a new mood episode or a new manic episode, but not a new depressive episode. Field studies with extended follow-up periods support the effectiveness of lithium salts for the long-term prevention of mood episodes. The recommendation for prevention is the same for adolescents and adult patients. |

| Strength of the recommendation | A | D | A |

| Formula | No. of patients treated with ECT in each autonomous community×100,000 inhabitants | (No. of patients with antipsychotic medication with baseline and annual monitoring of lipid profile and blood glucose/No. of patients with antipsychotic medication)×100 | (No. of patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder type I and treatment with Li [alone or in combination]/No. of patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder type I and drug treatment)×100 |

| Explanation of terms | ECT performed: includes public and private level | • Antipsychotic medication: includes any type of antipsychotic drug• Monitoring parameters: blood glucose and lipid profiles (total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol)• Baseline monitoring: before the start of treatment• Annual monitoring: every 12 months after the start of treatment | • Treatment with lithium: intake of lithium by itself or in combination with another drug• ICD-10 code for bipolar disorder type 1: F31; F31.1; F31.2; F31.3; F31.4; F31.5; F31.6 and F31.8 |

| Population | All the inhabitants of the autonomous community | All patients with antipsychotic medication.a. If they have been taking antipsychotics for more than 1 year: monitoring in the 12 months prior to the measurement of the indicator.b. If they have been taking antipsychotics for less than 1 year: monitoring before initiating treatment. | All patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder during the evaluation period |

| Resource (unit of analysis) | Autonomous community (aggregated data from the ECT units in each community) | Outpatient care (adult mental health center or outpatient clinic of the hospital) | Outpatient care (adult mental health center or outpatient clinic of the hospital) |

| Type | Process | Process | Process |

| Source of data | ECT working group in the Spanish Society of Biological Psychiatry. Annual indicator | Clinical documentation and outpatient pharmacy database | List of patients from the adult mental health center or patients of the outpatient clinic and pharmacy (chronic medications) |

| Bibliography | 1. CONSENSO ESPAÑOL sobre la terapia electroconvulsiva. 2018. Sociedad Española de Psiquiatría Biológica.2. Bernardo M, et al. Dignificando una terapia electroconvulsiva basada en la evidencia. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2015;8(2).3. Leiknes KA, et al. Contemporary use and practice of electroconvulsive therapy worldwide. Brain Behav. 2012;2(3):283–344.4. Vera I, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy practice in Spain: a national survey. J ECT. 2016;32(1):55–61.5. Song G-M, et al. Treatment of adults with treatment-resistant depression: electroconvulsive therapy plus antidepressant or electroconvulsive therapy alone? Evidence from an indirect comparison meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(26):e1052.6. Hermida AP, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy in depression: current practice and future direction. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2018;41(3):341–53.7. Haq AU, et al. Response of depression to electroconvulsive therapy: a meta-analysis of clinical predictors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(10):1374–84.8. UK ECT Review Group. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361(9360):799–808. | 1. Cooper SJ, et al. BAP guidelines on the management of weight gain, metabolic disturbances and cardiovascular risk associated with psychosis and antipsychotic drug treatment. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(8):717–48.2.2. Bernardo M, et al. Recomendaciones para la monitorización y promoción de la salud física en el paciente con esquizofrenia y otros trastornos mentales graves. Departament de Salut; 2014.3. Falkai P, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, Part 1: Acute treatment of schizophrenia. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2005;6(3):132–91.4. Falkai P, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, Part 2: Long-term treatment of schizophrenia. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2006;7(1):5–40.5. Grupo de Trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre la Esquizofrenia y el Trastorno Psicótico Incipiente. Fòrum de Salut Mental, coordinación. Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre la Esquizofrenia y el Trastorno Psicótico Incipiente. Madrid: Plan de Calidad para el Sistema Nacional de Salud del Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Agència d’Avaluació de Tecnologia i Recerca Mèdiques; 2009. Guía de Práctica Clínica: AATRM. N° 2006/05-2.6. Saiz Ruiz J, et al. Consenso sobre la salud física del paciente con esquizofrenia de las Sociedades Españolas de Psiquiatría y de Psiquiatría Biológica. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2008;36(5):251–64.7. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(1–2):1–30. | 1. BALANCE investigators and collaborators, Geddes JR, et al. Lithium plus valproate combination therapy versus monotherapy for relapse prevention in bipolar I disorder (BALANCE): a randomized open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9712):385–95.2. Grupo de Trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre Trastorno Bipolar. Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre Trastorno Bipolar. Madrid: Plan de Calidad para el Sistema Nacional de Salud del Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Universidad de Alcalá. Asociación Española de Neuropsiquiatría. 2012. UAH/AEN Núm. 2012/1.3. Chia MF, et al. Early intervention for bipolar disorder – do current treatment guidelines provide recommendations for the early stages of the disorder? J Affect Disord. 2019;257:669–77.4. Yatham LN, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97–170.5. González-Pinto A, et al. Can lithium salts prevent depressive episodes in the real world? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28(12):1351–9. |

ETC: electroconvulsive therapy.

Despite attempts to ensure that the indicators were applicable at different care resources and levels, a number of indicators only were applicable at the inpatient level (indicators 4, 9, 14, and 16), and others only were applicable at the outpatient or community care levels, such as outpatient consultations or mental health center (indicators 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, 13, and 15). A selection of indicators showed potential applicability at both levels (indicators 1, 10, and 11) (Table 1). Conversely, and in terms of type of indicator, only one of the indicators was categorized as a “result” type indicator (indicator 16), while all remaining indicators were classed as “process” type indicators.

In the two participating hospitals of the pilot study, the evaluation was carried out mainly for the hospital-level indicators. This approach was chosen as the most appropriate, since performing the assessment at the outpatient level at the mental health center presented some difficulties, particularly when it came to cross-referencing diagnostic databases with outpatient pharmacy databases (chronic patient prescriptions). Furthermore, both hospitals showed complete (100%) overlap in the identification of these indicators, meaning that both centers had automatic access to the necessary data which contained the numerator and denominator of the indicator. In order to implement this in further centers, it will be important to consider the level of development of the databases and software programs. In Table 1, the 5 indicators that can automatically generate results are highlighted in bold (indicators 3, 4, 9, 10, and 16). Indicator 1 “Electroconvulsive therapy”, should also be added to this group. While not applicable at the level of each center individually, it is applicable at the national level based on aggregated data from the electroconvulsive therapy units in each autonomous community or hospital and would be processed by the “Electroconvulsive Therapy Working Group in the Spanish Society of Psychiatry and Mental Health (SEPSM)”.

DiscussionIn this paper, 5 quality indicators ready for immediate implementation in the Health Care System were identified. Regarding major depression, the automatic indicator was “follow-up with patients with major depression” (indicator 3), which refers to the minimum number of annual visits after the diagnosis, as established in the international literature.10 For schizophrenia, only one indicator could be generated automatically: “Treatment of schizophrenia with clozapine” (indicator 4). This indicator may be particularly useful in comparing the variability of prescription and differences between work centers. A study on second psychotic episodes showed that the use of clozapine after the first episode was associated with higher remission rates.11 For bipolar disorder, two automatic indicators were identified: “use of lithium for patients with bipolar disorder” (indicator 9) and “avoiding the use of valproate in women of childbearing age” (indicator 10). These two automatic, easy-to-apply indicators could significantly contribute to improving clinical care,12 patient health,13,14 and the safety of women and their children.15 In addition, one indicator applicable to all three pathologies which is currently used in hospital centers was identified: “hospital readmission at 30 days in major depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder” (indicator 16). The group of experts deemed that the standard of quality is set at approximately 7%.

In relation to the indicators regarding the use of clozapine in the treatment of schizophrenia and the use of lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder, no internationally defined quality standards exist. This may be due to their characteristics and the lack of incentives for prescribing them, however, it is important to note that they are widely used in mental health care settings. Recent studies indicate that clozapine can be administered shortly (e.g., a few weeks) after a first psychotic episode after not responding to two initial treatments.16 Unfortunately, there are health professionals and centers that do not use clozapine or lithium and this could be perceived as bad praxis. To respond to this challenge, the experts agreed to propose the following standards as a guideline: a minimum of 10% of schizophrenia patients treated with clozapine and 70% of bipolar patients treated with lithium (this refers to type I bipolar disorder). In the case of clozapine, 10% was chosen as standard based on the evidence that 20–30% of patients are treatment resistant, and clozapine is the antipsychotic that has shown the highest rate of response in these cases.17 Furthermore, lithium was chosen as a standard as it is a first-line medication for treatment according to all clinical guidelines for bipolar disorder treatment, and in terms of efficacy, it has not been surpassed by any other mood stabilizers.18 Although the indicator values may vary according to where they are applied (e.g., hospital samples versus community samples, etc.), their divergence from the proposed standard should be minimal.

While we have demonstrated the importance of the 5 most prominent indicators, the remaining 11 are also of clinical significance. For example, electroconvulsive therapy should be listed among the range of possible treatments for patients with treatment-resistant depression and other severe pathologies.19 Additionally, treatment for depression should be prolonged beyond 9 months for at least 30% of patients.20 For schizophrenia, it is important to continue drug therapy beyond the acute phase of the first episode, monitor the patient's weight, glucose and lipid profile, and consider the use of extended-release antipsychotics in all patients at risk of treatment discontinuation. We have already mentioned the importance of considering the possible use of lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder, and avoiding the use of valproate in women of childbearing age, but a third indicator is equally important: discontinuing depression medication during manic phases, as not only do they fail to improve symptoms, they may also worsen them.21 Unfortunately in current practice, many professionals forget to discontinue depression medication in patients with manic or mixed symptoms.22 Indicators applicable to all three conditions include monitoring for suicidal behavior after release from the emergency room, in line with the “Suicide Risk Code” that has already been implemented in some regions,23,24 follow-up after the first episodes,25 reducing mechanical restraints to a minimum,26 avoiding polytherapy for major depression and schizophrenia, and reducing readmissions. Applying all of these indicators as standardized clinical practice would greatly improve the quality of health care in the Spanish Health Service.

Quality of care is a major pillar of humanization in Psychiatry.10,27 The set of indicators selected in this study, including a feasibility pilot study, allows for the monitoring of the quality of care of patients with major depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. This catalog of indicators aimed to help both health care professionals and administrators who are in a prime position to detect changes based on the implementation of best practices. In doing so, and by ensuring that these practices can be evaluated in the various information systems of the Spanish Health Service, results can be obtained to demonstrate their clinical significance. Importantly, the methodology followed guidelines used by other indicator-based monitoring systems.4,28

To support the use of indicators, their automatic generation is crucial. Although automatically generated indicators cannot yet be generalized across all selected indicators, the possibility to achieve this is demonstrated in the 5 core indicators highlighted in the present study (Table 1). The main reason for the non-automatic generation for the rest of the indicators is the continued development of information management systems in the health care centers or other facilities, which may be improved in the future.

As mentioned by Bernardo et al., quality indicators in mental health are less developed in comparison to other areas of health.8 Nevertheless, their article did not verify the possibility of making indicators automatic. Current computing systems for such severe pathologies, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, allow for comparisons in the use of specific treatments across centers and this technological advance offers a clear opportunity for health care professionals to implement in standard clinical practice. As a result, mental health units can use the same strategies for quality improvement that are used in other countries.29–31

The implementation of this proposal into practice is based on an environment of voluntary participation of hospital and community mental health centers. This set of indicators can serve as a guide to successfully adapt and prioritize each center, define their balanced scorecard, and facilitate comparisons and the implementation of continuous improvement strategies.

Strengths and limitationsThe main limitation of the study is the pilot study in itself, since it has been carried out only at two centers, being both of them hospital settings, instead of also including community care units. In addition, 9 out 16 indicators (those to be used at outpatient settings) were not evaluated in the pilot study. Another limitation is that the authors selected just one indicator of “results”, versus 15 measuring “processes”. It would be desirable a more balanced selection between “results” and “process” indicators.

One of the main limitations of this and other similar studies is that the evidence level of mental-health quality indicators is variable. To mitigate this limitation, we asked a panel of experts and one specialist in health indicators to help refine them by mutual agreement. In addition to considering their clinical significance, the feasibility of calculation for the indicator and its acceptability were also kept in mind. As such, there may be other equally valid indicators that have not been included in this group. As this proposed set of indicators is intended to be applied from the first moment by mental-health services, in the future, as technical and therapeutic advances occur, other quality indicators could be incorporated or could replace existing indicators. The most important contribution of this study is to reduce the list of indicators to 16, selecting those that are most feasible (automatic) and relevant, and testing them though a pilot study. More studies about implementation of quality indicators should be done in order to test the generalizability of results, and the variety of contexts where the standards are meant to be implemented.

Other limitations of this study are that patient reported outcome measures (PROMs)32 and Patient reported experiences measures (PREMs)33,34 were not included and the fact that patient representatives and caregivers did not provide any direct contributions. Although this limitation can be improved in future studies, it is important to note that the aim of this study was to look for objective and automatic indicators, which is not compatible in current practice with the subjective nature of quality results as perceived by end users.

The main strength of this project is its novelty in Spain, as a response to a concern to ensure and improve the quality of mental health care. This study seeks to promote the achievement of quality health care standards so that patients can count on an appropriate environment and a measure of proven quality care in a range of health care facilities across the health system.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, we present a set of “results” and “process” indicators, which were prepared by consensus and successive iterations and distillation. They are in line with other European studies in recent years that sought to improve the quality of treatments for patients with major depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder, and which, as shown, can be collected automatically. The 16 indicators selected are centered on aspects of care related to accessibility, suitability of the diagnosis and treatment, and safety.

Having a standard list of indicators in every health center of the country will make it possible, firstly, to establish care objectives and monitor and evaluate the work of all the services. This could provide us with the opportunity to detect nonconformity to standards, analyze this nonconformity, and correct it accordingly. Secondly, this approach would contribute to a comparative study of the services to evaluate indicators with improvable results, and create a space for mutual reflection for collaborative evaluation, as well as encourage the achievement of excellent results. Improving quality will lead to better patient care and more transparency with respect to mental health management in Spain.

FundingSpanish Foundation of Psychiatry and Mental Health and Janssen-Cilag (unrestricted grant).

Conflicts of interestEV has collaborated on research activities, teaching or consulting, not related to this study, with the following companies: AB-Biotics, Abbvie, Aimentia, Angelini, Biogen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Casen-Recordati, Celon, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ethypharm, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, GH Research, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Janssen, Lundbeck, Organon, Orion, Otsuka, Rovi, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, Takeda and Viatris.

JMMM has collaborated on research activities, teaching or consulting, not related to this study, with AbBiotics, Biohaven, Exeltis, Janssen, Lundbeck, Medtronic and Novartis.

MBA has collaborated on research activities, teaching or consulting, not related to this study, with AB-Biotics, Angelini, Casen-Recordati, Janssen-Cilag, Menarini, Rovi and Takeda.

VPS has collaborated on research activities, teaching or consulting, not related to this study, with CIBERSAM, ISCIII, UE H2020, EAAD, Compass, Novartis, Lundbeck, Janssen, Otsuka, GSK, Exeltis, Abbvie, Abbot, Esteve and Angelini.

CMR has collaborated on research activities, teaching or consulting, not related to this study, with Angelini, Esteve, Exeltis Janssen, Lundbeck, Neuraxpharm, Nuvelution, Otsuka, Pfizer, Servier and Sunovion.

CAL has been a consultant or has received fees or grants from Acadia, Angelini, Biogen, Boehringer, Gedeon Richter, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Medscape, Minerva, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Sage, Servier, Shire, Schering Plough, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Sunovion and Takeda.

JBG has no conflicts of interest.

MMC has collaborated on research activities, teaching or consulting, not related to this study, with Angelini, Casen-Recordati, Esteve, Exeltis, Janssen, Neuraxpharm, Novartis, Lundbeck, Pfizer and Sanofi-Aventis.

DPV has collaborated on research activities, teaching and consulting, with no direct relation to this study, with Angelini, Janssen, Lundbeck and Servier.

AGPA has collaborated on research activities, teaching or consulting, not related to this study, with Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Angelini, Exeltis, Novartis and Takeda.

The authors would like to thank the Avedis Donabedian University Institute for their participation in the preparation and design of the quality indicators, as well as the Research Unit of Luzán 5 Health Consulting (Madrid), Fernando Sánchez Barbero PhD, and Derek Clougher for their support in preparing this manuscript.