Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has had a major impact on our lives, both socio-economically and in terms of our physical and mental health. On 30 January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a public health emergency.

On 11 March 2020, the pandemic was officially declared. To date, 102,392 people have died worldwide by COVID-19, while many others have been affected directly or indirectly.1

The pandemic has had a disruptive socio-economic effect: approximately one third of the world's population was locked down and severe restrictions on freedom of movement were imposed, leading to a drastic reduction in economic activity and a parallel rise in unemployment. At the healthcare level, there has been an unprecedented overflow and collapse of hospitals.2

It is hard to imagine a health problem with a greater impact than COVID-19, but the truth is that suicide is one of the most important public health problems and one of the main causes of death in our country.3 The real magnitude of this problem is underestimated and has been increasing in recent years. According to data provided by the National Statistics Institute (INE), 3941 people took their own lives in Spain in 2020, an increase of 7.4% over 2019. The epidemiological and social impact of suicide involves not only mortality due to completed suicide, but also suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, as well as the consequences for the quality of life of the population.4

Unlike COVID-19, suicide is a health problem affecting young people. Currently, suicide is the leading cause of unnatural death in our country in people aged 15–29 years.5 Of concern, suicide attempts in this age group increased by 250% in 2020 compared to previous years.3

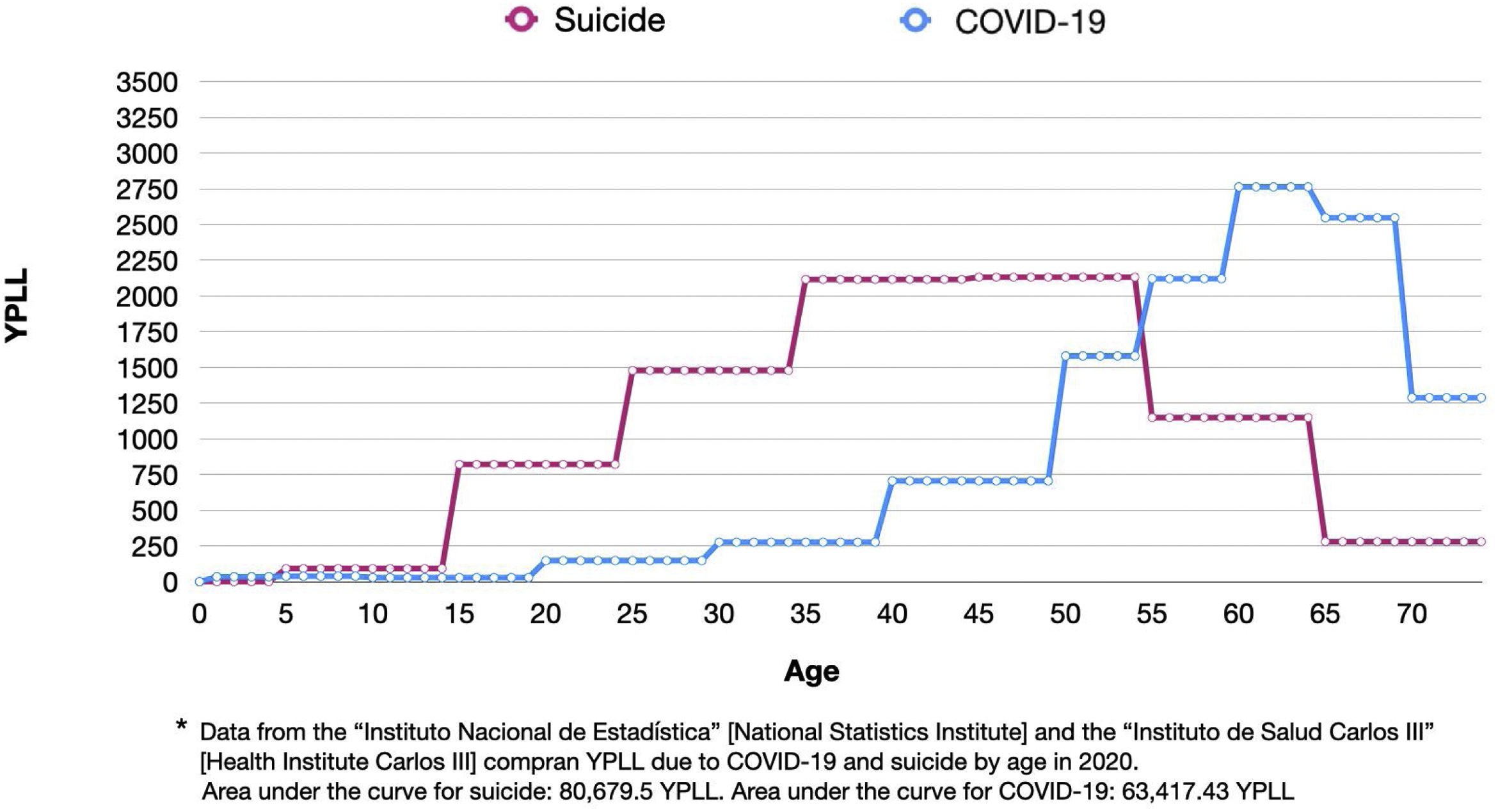

The aim of this study is to quantify the impact of suicide in terms of years of potential life lost (YPLL) and to compare it with the YPLL by COVID-19 in the year 2020 in Spain. YPLL below the age of 75 is an illustrative indicator of the loss suffered by society because of premature deaths.6

For this study, we used data on deaths by age group caused by COVID-19 and suicide as provided by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III [Carlos III Health Institute]7 and the Instituto Nacional de Estadística [National Institute of Statistics]3 for ages 0–75 years, from 1 January to 31 December 2020. To calculate the YPLL, we subtracted the average age of each age group to age 75. We multiplied the result by the number of deaths corresponding to each age group and then summed the results to obtain the total YPLL by each cause.

In 2020, YPLLs as a result of suicide were 80,679.5, versus 63,417.43 YPLLs due to COVID-19, a difference of 17,262.1 YPLLs. These results are illustrated in Fig. 1.

We observed that the death rates with the greatest weight in the case of COVID infection are located in the older age groups, the most prominent being between 60 and 69 years of age, age groups in which most deaths are often related to cardiovascular risk factors, pulmonary diseases or complications of other pathologies. However, the greatest number of deaths by suicide occur in the 25–54 age group.5 That is why YPLL are higher for suicide than for COVID-19 in our country.

Our results contrast with the study by Porras-Segovia et al. who compared YPLLs from COVID-19 in 2020 with those produced by suicide in 2019 in the United States, finding that COVID-19 had produced more YPLLs than suicide, albeit with a narrow difference.8

The scope and implications of our findings encompass multiple aspects. The greatest losses in work productivity are concentrated in young people, as well as a decrease in natural population growth through a reduction of birth rates, which implies a rationalization and restructuring of health spending. We must also remember the suffering that suicidal behavior entails for the person and his or her social environment.9

There are still great challenges in suicide prevention. It is necessary to address this problem through effective primary and secondary prevention, diagnosis of the precipitating or underlying pathology, as well as improvements in treatment, early diagnosis and allocation of funds.

Since March 2020, a major effort has been made to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic. In comparison, suicide remains an orphan disease. Evidence shows that, with proper healthcare planning, suicide can be prevented.10 A comprehensive approach is required for a better understanding of the predisposing and precipitating factors that contribute to suicide behavior, and a coordinated involvement of health professionals and healthcare planning is required to prevent suicide and increase the quality of life of the population.

Our research team wants to thank the support received from “Instituto de Salud Carlos III” (CM19/00026), the “Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades” (RTI2018-099655-B-I00; TEC2017-92552-EXP) and the Alicia Koplowitz Foundation.