Bipolar disorder is a condition that causes distress even for euthymic patients, having an impact on functional capabilities and quality of life. Personal and social variables are potential sources of distress. Yet, there is a lack of measures to identify specific distress in bipolar disorder. This study describes the development and evaluation of a brief measure for assessing distress in patients with bipolar disorder. We also identify associations with related constructs such as functioning, stigma, and personal beliefs regarding mental illness.

Material and methodsWe used a sample of 101 euthymic bipolar outpatients. Psychological assessment consisted of the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) and the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) to establish euthymia. Distress was assessed with Distress on Bipolar Patients-Short (DISBIP-S); associated variables were assessed with the Functioning Assessment Short Scale (FAST), the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI), and the Personal Beliefs about Illness Questionnaire (PBIQ).

ResultsThe DISBIP-S has strong internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=0.90), and medium-high correlation coefficients with the time since last relapse (r=−0.401), predominant polarity (r=0.309), HDRS (r=−0.644), FAST (r=0.453), ISMI (r=0.789), and PBIQ (r=−0.796). Taken together, the scores on the ISMI, and PBIQ and the time since last relapse together explain 69.2% of the variability in distress.

ConclusionsThe DISBIP-S can be used as a first step to develop interventions aimed at dealing with problematic personal beliefs and interpersonal sources of distress. Reducing distress experienced by bipolar disorder patients could help improve their quality of life and daily functioning.

In the last few years, a person-centered approach in mental health1 is receiving more attention in scientific literature. Particularly, regarding bipolar disorder (BD), different researchers have studied how illness impact on patients’ lifes,2 and how do they manage such difficulties.

As Gask and Coventry1 stated: “by listening to what the patient says, and following up key cues that indicate what the nature of their problems might be, and responding empathically to their distress, the health professional seeks to communicate through a ‘patient-centred’ consultation” (p. 140). However, when dealing with distress in bipolar disorder, there is a lack of measures to perform such assessment in a standardized way.

Objective consequences of bipolar disorder (e.g. economic losses after a manic episode) have an impact in functioning and quality of life, although subjective perceptions of these consequences may imply high levels of distress even when real functioning (e.g. autonomy, work functioning) is not that impaired. Whereas quality of life is defined by the WHO as a multidimensional concept that includes physical, emotional, social, and spiritual well-being,3 psychological distress can be defined4 as a unique discomforting, emotional state experienced by an individual in response to a specific stressor or demand that harms, in some way-temporary or permanent-, the person. Concerning BD, distress associated with the illness could be conceptualized as how patients perceive BP affects them at different levels,5 namely: beliefs related to their ability to achieve personal and professional goals, cognitive complaints, internal hopelessness and stigma, feelings of incomprehension in their relationships, and difficulties in dealing with stress or coping with the disorder, among others.

A meta-synthesis of qualitative research,2 assessing how distress is experienced by people with BD, revealed a number of issues experienced as distressing by those patients: diagnosis and medication intake, loss of control and autonomy, uncertainty, threat of symptoms, relationships and social support, stigma and fear of relapse. Most of the studies report interpersonal issues as distressing. That is, BD patients not only may have personal suffering concerning their illness and its consequences, but also significant interpersonal distress along the course of their illness. In fact, a recent meta-analysis6 has shown that BD patients experience reductions in their quality of life, even when euthymic.

For those patients, reactions to the diagnosis imply a high degree of distress7 as well. Beliefs regarding BD and its perceived consequences in daily life deserve more attention, as a high degree of functional impairment in BD patients has been documented.8 In this regard, meta-cognitive processes such as self-compassion have been demonstrated to act as mediators of psychological distress.9 High degree of distress is associated to more risk of suicide, so it seems necessary to have a distress measure as part of clinical and research monitoring.10 Early intervention with the aim of treating not only symptoms but also psychological distress, has been demonstrated to improve quality of life, functional recovery and help-seeking behaviors.11

At an interpersonal level, issues like stigma may play an important role in worsening distress, disability, and quality of life.12 Self-stigma,13 a phenomenon in which patients may internalize stereotypes about themselves, deserves attention too. In addition, caregivers can suffer a significant degree of distress14,15 and may be at risk of developing expressed emotion, a measure of criticism, hostility, and/or emotional overinvolvement.16 As Miklowitz et al.17 found, patients who were more distressed by their relatives’ criticisms had more severe depressive and manic symptoms and fewer days well during the study year than patients who were less distressed by criticisms. This justifies the relevance of identifying patients’ interpersonal distress as a first step to develop strategies to help them manage it.14,18,19

A BD-specific distress scale to be used as a follow-up and as an outcome measure in both research and clinical practice is advisable. Although different scales are aimed at assessing quality of life20 and functioning in bipolar disorder,8 there is only one study5 aimed at developing a measure to assess distress in BD patients. In that study, an initial pool of 46 items based on common concerns communicated by patients in outpatient appointments was developed by the authors and then screened by expert raters. After that, a pilot study was conducted and a 15-item scale composed of three cognitive, interpersonal and self-management dimensions were identified after factorial analysis. The process used to develop the measure has been published elsewhere.5 However, a larger sample and the use of additional measures to assess convergent and discriminant validity with related constructs such as stigma, personal beliefs or functioning was required. This also helps to shed light on the associations between those variables.

Given the above, the aim of this study is to look for further evidence of the adequacy of a short measure (DISBIP-S) to assess distress in euthymic BD patients. More specifically, we aim to test the psychometric properties previously reported (i.e., internal consistency, construct validity,) in a larger sample, as well as to analyze convergent and discriminant validity. We also aim to identify associations with other constructs potentially related to distress (i.e. functioning, stigma and personal beliefs regarding mental illness) and their role in predicting levels of distress. We expect to find that distress is predicted by functioning, stigma and personal beliefs regarding mental illness. No associations are expected between distress and variables such as age and gender.

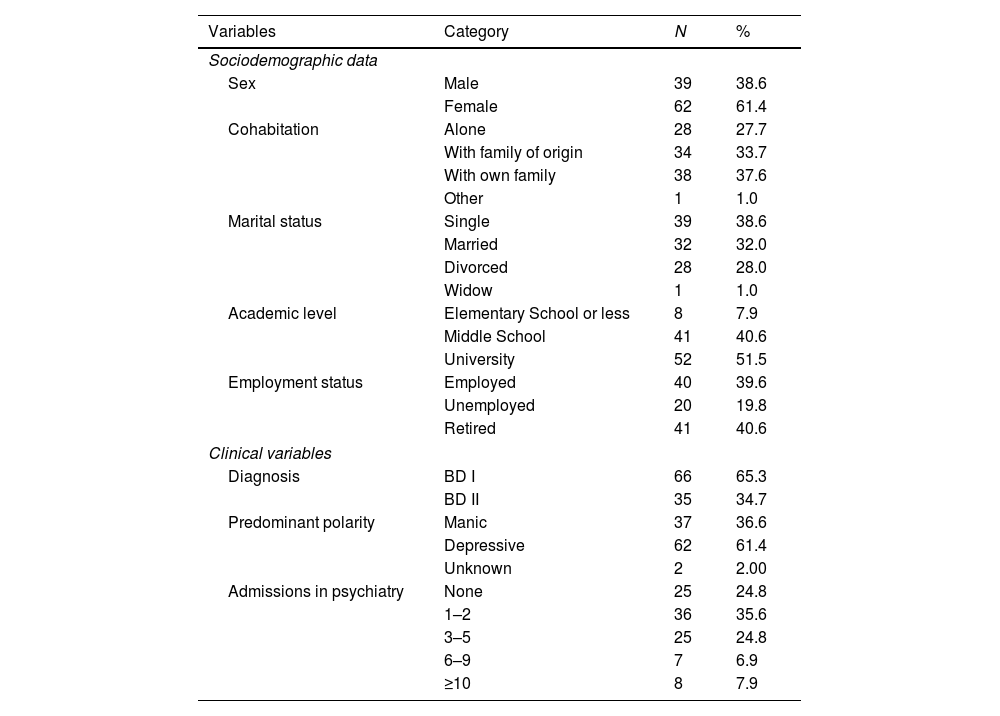

Materials and methodsParticipantsA convenience sample of 101 bipolar outpatients was recruited at the Ramón y Cajal Hospital and the Bipolar Association of Madrid, Spain. The sample was drawn from patients who came to a regularly scheduled visit and were willing to give informed consent. Outpatients aged 24–72 years (mean=48.72±11.56); 61.4% were female. Average years with BD was 23.42 (sd=11.67, range: 3–55). The average age of the onset was 25.24 years (sd=9.55, range: 12–56). The years with the diagnosis averaged 17.06 (sd=11.61, range: 0–52). The time since the last relapse averaged 2.36 years (sd=4.00, range: 0.10–20). As noted in Table 1, approximately two thirds of the cases were diagnosed with type I BD and the predominant polarity was depressive. More than two thirds of the participants had required one or two psychiatric admissions.

- -

Inclusion criteria: For inclusion in the study, participants had to score ≤7 on both the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)21 and the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D)22 to ensure euthymic state. Patients should have been euthymic for at least one month.

- -

Exclusion criteria: Patients with co-morbid diagnoses of personality disorder and substance abuse, as well as those with concomitant chronic physical pathologies were excluded from the current study.

Sociodemographic and clinical data.

| Variables | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic data | |||

| Sex | Male | 39 | 38.6 |

| Female | 62 | 61.4 | |

| Cohabitation | Alone | 28 | 27.7 |

| With family of origin | 34 | 33.7 | |

| With own family | 38 | 37.6 | |

| Other | 1 | 1.0 | |

| Marital status | Single | 39 | 38.6 |

| Married | 32 | 32.0 | |

| Divorced | 28 | 28.0 | |

| Widow | 1 | 1.0 | |

| Academic level | Elementary School or less | 8 | 7.9 |

| Middle School | 41 | 40.6 | |

| University | 52 | 51.5 | |

| Employment status | Employed | 40 | 39.6 |

| Unemployed | 20 | 19.8 | |

| Retired | 41 | 40.6 | |

| Clinical variables | |||

| Diagnosis | BD I | 66 | 65.3 |

| BD II | 35 | 34.7 | |

| Predominant polarity | Manic | 37 | 36.6 |

| Depressive | 62 | 61.4 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 2.00 | |

| Admissions in psychiatry | None | 25 | 24.8 |

| 1–2 | 36 | 35.6 | |

| 3–5 | 25 | 24.8 | |

| 6–9 | 7 | 6.9 | |

| ≥10 | 8 | 7.9 | |

This is a cross-sectional study with an ex-post facto design. After receiving the approval of the Ramon y Cajal Hospital Ethics Committee, the DISBIP-S5 was applied to the selected participants, together with a socio-demographic questionnaire, the YMRS21 and HAM-D22 scales to verify euthymia and to assess the possible existence of subsyndromal mood symptoms. Three additional scales were applied to half of a randomly selected subsample: the FAST8 scale to asses functioning, the ISMI23 to assess factors associated with stigma, and the PBIQ24 to assess negative beliefs concerning BD. No differences were found in any of the sociodemographic or clinical variables, between the two halves of the sample, so both were equivalent. Previously, informed consent was required, and confidentiality was guaranteed to the participants.

Instruments- -

Sociodemographic data: A questionnaire was used to collect these data. Predominant polarity was coded as 1 for manic-hypomanic, and as 2 for depressive.

- -

Mood symptoms: To assess euthymia, the Spanish version of the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS),21 and the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D)22 were used.

- -

Functioning: functioning at different levels was assessed with the Functioning Assessment Short Scale (FAST),8 a brief instrument designed to assess the main functioning problems experienced by bipolar patients (e.g. autonomy, cognitive or interpersonal). It comprises 24 items that assess impairment or disability in six specific areas of functioning: (1) Autonomy, (2) Occupational functioning, (3) Cognitive functioning, (4) Financial issues, (5) Interpersonal relationships, and (5) Leisure time. The higher the scores, the worse the functioning.

- -

Stigma: as measured by the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI)23 that assesses the subjective experience of stigma, with five subscales measuring: (1) Alienation or “the subjective experience of being less than a full member of society or having a ‘spoiled identity”’ (p. 36). (2) Stereotype endorsement, or agreement with common stereotypes about people with mental illness. (3) Discrimination Experience, that “captures respondents’ perception of the way that they currently tend to be treated by others” (p. 36). (4) Social withdrawal, that deals with behaviors to prevent rejection, and (5) Stigma resistance, that intends to portray the experience of being unaffected by the stigma. As this factor has a positive valence, it has been reverse-coded for the analyses, so the higher the scores, the higher the perceived stigma.

- -

Personal beliefs: measured by the Personal Beliefs about Illness Questionnaire (PBIQ)24 which assesses, with 16 items, the degree to which participants accept social and scientific beliefs about mental illness as a statement about themselves. The questionnaire has five scales: (1) Self as illness, that assesses “the extent to which subjects believe that the origins of their illness lies in their personality or psyche” (p. 389). (2) Control over illness, that assesses the extent to which patients believe that they can take control of it; (3) Stigma, to assess the extent that patients believe their illness is a social judgment on them. (4) Social containment, refers to support for social segregation and control strategies for dealing with those with mental illness, and (5) Expectations, that assesses whether patients feel the illness affects their capacity for independence. Each question is rated on a four-point scale from strongly disagree (4) to strongly agree (1), so, the lower the scores the more the negative beliefs about themselves.

- -

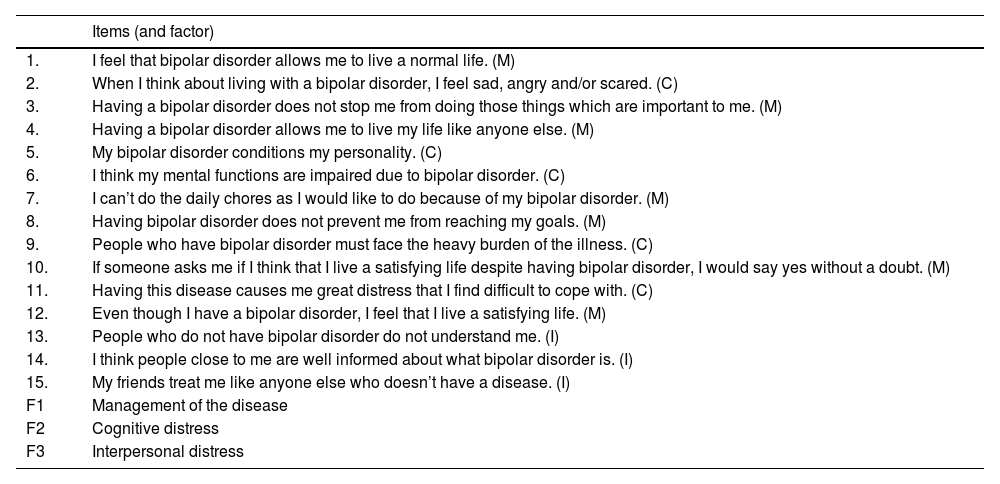

Distress: To assess the perceived distress by BD patients, the DISBIP-S (Short Distress Scale for Bipolar Disorder),5 which is composed by 15 items grouped in three dimensions (Table 2), was used. It evaluates: (1) Cognitive distress, that assesses the perceived discomfort associated to changes in emotions, personality, and cognitive functions. (2) Interpersonal distress, that assesses the impact of the disorder on the patient's social relationships, and (3) Management of the disease, that assesses the extent to which patients feel capable of handling their own disease. The higher the scores, the higher the distress.

Table 2.DISBIP-S items.

Items (and factor) 1. I feel that bipolar disorder allows me to live a normal life. (M) 2. When I think about living with a bipolar disorder, I feel sad, angry and/or scared. (C) 3. Having a bipolar disorder does not stop me from doing those things which are important to me. (M) 4. Having a bipolar disorder allows me to live my life like anyone else. (M) 5. My bipolar disorder conditions my personality. (C) 6. I think my mental functions are impaired due to bipolar disorder. (C) 7. I can’t do the daily chores as I would like to do because of my bipolar disorder. (M) 8. Having bipolar disorder does not prevent me from reaching my goals. (M) 9. People who have bipolar disorder must face the heavy burden of the illness. (C) 10. If someone asks me if I think that I live a satisfying life despite having bipolar disorder, I would say yes without a doubt. (M) 11. Having this disease causes me great distress that I find difficult to cope with. (C) 12. Even though I have a bipolar disorder, I feel that I live a satisfying life. (M) 13. People who do not have bipolar disorder do not understand me. (I) 14. I think people close to me are well informed about what bipolar disorder is. (I) 15. My friends treat me like anyone else who doesn’t have a disease. (I) F1 Management of the disease F2 Cognitive distress F3 Interpersonal distress

IBM@ SPSS@ and Amos v.23 were used for the analyses. Internal consistency of the measures was tested by means of reliability analyses performed with Cronbach's alpha statistic for the different scales and subdomains. Confirmatory Factor Analysis was used to test the construct validity, that is, the goodness of fit of the three-factor structure model of the DISBIP-S. Maximum likelihood parameter estimation was utilized as multivariate normality was identified.25 Convergent and discriminant validity was conducted by means of Pearson's correlations between the DISBIP-S and selected variables. To identify the variables that best predict distress, a linear regression was also performed. An alpha level=.05 was set for all the analyses.

ResultsTable 3 summarizes the reliability analyses performed for all the measures. These results support the reliability of the DISBIP-S and its subscales, as well as the adequacy of the remaining measures and most of their subscales. CFA analyses were performed with the DISBIP-S and the three-factor model shows a good fit to the data: χ2 (87)=116.559; p=0.019; χ2/df=1.339. The CFI was 0.95; RMSEA was 0.58 (90%CI: 0.025–0.084); the correlation between latent variables Management and Cognitive was 0.764 (covariance=3.061, SE=0.723); the correlation between latent variables Interpersonal and Cognitive was 0.586 (covariance=1.688, SE=0.573); the correlation between latent variables Interpersonal and Management was 0.817 (covariance=2.859, SE=0.771).

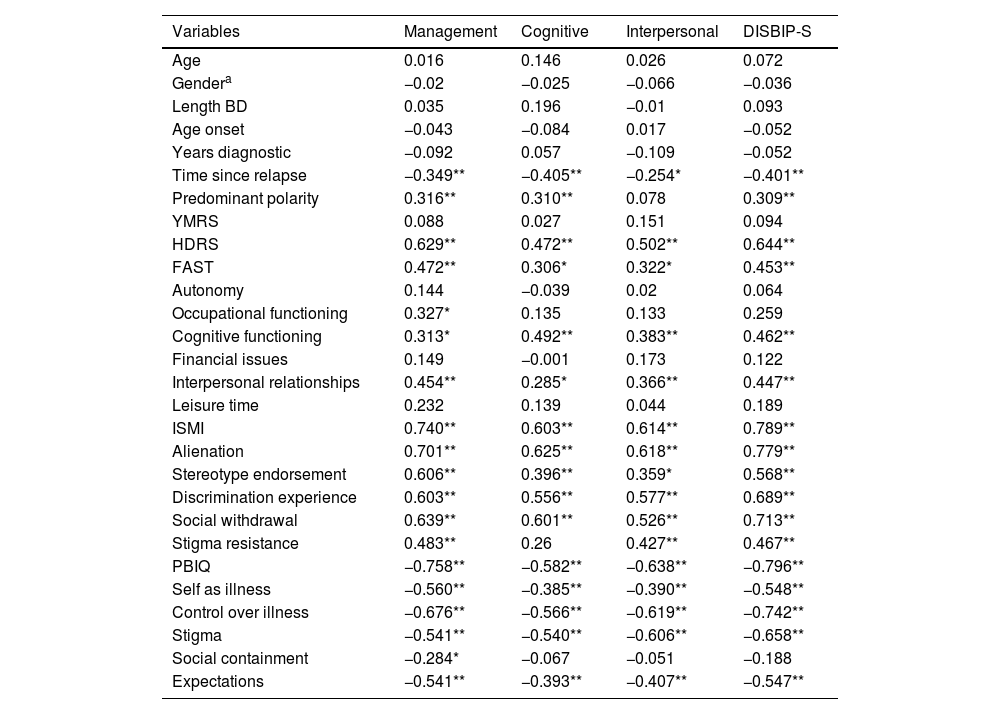

Concerning analysis on convergent and discriminant validity, Table 4 shows that neither age nor clinical variables such as length of the condition were associated to distress. When the predominant polarity is depressive, distress is higher; depressive symptoms, as measured by the HDRS, are associated to distress. Worse functioning (i.e. FAST) is associated to distress, above all to Cognitive functioning and Interpersonal relationships. Stigma (i.e. ISMI) and all its subscales are also associated to distress. Similarly, personal beliefs (i.e. PBIQ) are significantly associated to distress as well, as are its subscales, except for Social containment which is only significantly associated to Management.

Correlations between selected variables and distress.

| Variables | Management | Cognitive | Interpersonal | DISBIP-S |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.016 | 0.146 | 0.026 | 0.072 |

| Gendera | −0.02 | −0.025 | −0.066 | −0.036 |

| Length BD | 0.035 | 0.196 | −0.01 | 0.093 |

| Age onset | −0.043 | −0.084 | 0.017 | −0.052 |

| Years diagnostic | −0.092 | 0.057 | −0.109 | −0.052 |

| Time since relapse | −0.349** | −0.405** | −0.254* | −0.401** |

| Predominant polarity | 0.316** | 0.310** | 0.078 | 0.309** |

| YMRS | 0.088 | 0.027 | 0.151 | 0.094 |

| HDRS | 0.629** | 0.472** | 0.502** | 0.644** |

| FAST | 0.472** | 0.306* | 0.322* | 0.453** |

| Autonomy | 0.144 | −0.039 | 0.02 | 0.064 |

| Occupational functioning | 0.327* | 0.135 | 0.133 | 0.259 |

| Cognitive functioning | 0.313* | 0.492** | 0.383** | 0.462** |

| Financial issues | 0.149 | −0.001 | 0.173 | 0.122 |

| Interpersonal relationships | 0.454** | 0.285* | 0.366** | 0.447** |

| Leisure time | 0.232 | 0.139 | 0.044 | 0.189 |

| ISMI | 0.740** | 0.603** | 0.614** | 0.789** |

| Alienation | 0.701** | 0.625** | 0.618** | 0.779** |

| Stereotype endorsement | 0.606** | 0.396** | 0.359* | 0.568** |

| Discrimination experience | 0.603** | 0.556** | 0.577** | 0.689** |

| Social withdrawal | 0.639** | 0.601** | 0.526** | 0.713** |

| Stigma resistance | 0.483** | 0.26 | 0.427** | 0.467** |

| PBIQ | −0.758** | −0.582** | −0.638** | −0.796** |

| Self as illness | −0.560** | −0.385** | −0.390** | −0.548** |

| Control over illness | −0.676** | −0.566** | −0.619** | −0.742** |

| Stigma | −0.541** | −0.540** | −0.606** | −0.658** |

| Social containment | −0.284* | −0.067 | −0.051 | −0.188 |

| Expectations | −0.541** | −0.393** | −0.407** | −0.547** |

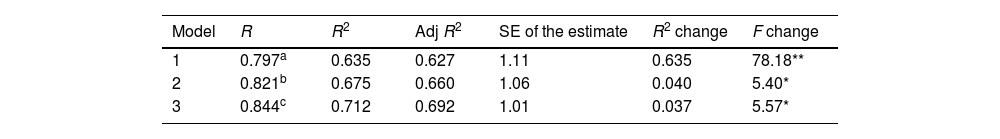

To identify the variables that best predict distress, we performed a multiple regression analysis (forward selection), with the total score on the DISBIP_S as the dependent or predicted variable and with time since last relapse, predominant polarity, and the scores on FAST, ISMI, and PBIQ as independent or potentially predictor variables. Table 5 depicts the Model summary. As can be noted, taking the predictors ISMI, PBIQ and time since last relapse together explain 69.2% of the variability in distress, as measured by the DISBIP-S. The F-ratio in the ANOVA tests was significant, meaning that the overall regression model is a good fit for the data. In other words, the three independent variables significantly predict the dependent variable [R2=71.2, F(3, 43)=35.418, p<0.001]. The variable with the highest explanatory power was ISMI that explains 63.5% of the distress (Beta=0.369; t=2.124; p<0.05), followed by PBIQ that explains 4% of such variable (Beta=−0.410; t=2.382; p<0.05), and by time since last relapse that explains 3.7% of the distress (Beta=−0.204; t=2.360; p<0.05). In sum, perceived stigma about the BD together with negative personal beliefs about it, and last time since relapse help explain a significant amount of the distress.

DiscussionThe main goal of this study was to provide a useful tool to assess distress in patients with bipolar disorder, that has previously showed high internal consistency as well as good content, construct and face validity in a pilot study,5 confirming not only these psychometric properties but also good levels of convergent and discriminant validity with a larger sample. This aim helps overcome a gap in the existing literature regarding psychometrically sound measures to assess the experience of distress that patients with bipolar disorder likely face even when euthymic.

The DISBIP-S which has previously demonstrated to have adequate reliability and face and content validity5 has shown highly satisfactory internal consistency and construct validity as evidenced by CFA, in this study. In this study, DISBIP-S also has demonstrated to have convergent validity by means of the high correlations with other measures closely related to distress, such as functioning, stigma, and problematic beliefs about the disorder. The moderate correlations with clinician-reported assessments of depressive symptoms (i.e. HDRS), and regarding predominant polarity offers additional support to that validity.

As in previous studies with BD patients, where more functional impairment was found during depressive rather than manic phases of illness,26–28 the current study found that depressive symptoms are more associated to distress, whereas manic does not seem to be associated. Potential explanations can be aligned with Goldberg et al.,26 who mentioned that, in contrast to depressive or subsyndromal depressive symptoms, low-grade symptoms of hypomania may actually enhance psychosocial functioning. It is noteworthy that participants who enrolled the study met the criteria of ≤7 on both YMRS21 and the HAM-D,22 but subsyndromal symptoms could be associated to the scores in the other scales as well, which strengthens the hypothesis of more distress in such participants. This also supports the findings previously reported by similar studies,5 which suggested that those with type II BD and those with depressive predominant polarity suffer higher levels of distress.

As expected, the present study reveals that demographic variables such as age, gender, length of BD, age of onset of the disorder, and years since diagnostic are not relevant in the explanation of the distress. These findings offer support to the discriminant validity of the DISBIP-S. Yet, time since last relapse is critical for experiencing distress. Therefore, the need for follow-up strategies and the use of measures, such as the one presented here, in order to offer support in case of relapses, as it has been proven to be a significant predictor of the distress.

Stigma appears as a key variable when explaining distress, in agreement with previous studies.2,13,23,29 Similar to Levy et al. statements,29 evaluations may seek to examine stigma-related experiences and determine their relationship to distress; interventions aimed at reducing the ill effects of stigma in those patients should be promoted.

Whereas interpersonal and social variables are clear sources of distress, it is also important to pay attention to the personal beliefs about the illness because, as this study has demonstrated, they are also significant predictors of distress. Although, as identified with the PBIQ, some beliefs relate to the others (e.g. stigma, social containment), some beliefs are personal in nature and relate to perceived loss of control (i.e. control over illness), purpose (i.e. expectations) and identity (i.e. self as illness). A previous literature review2 stressed those issues and the current empirical evidence offers additional support for the need to pay attention to patients’ perceptions, in order to better tailor treatments.

Both the preliminary study of DISBIP-S,5 and the current study were aimed to present the psychometric properties of DISBIP-S, specifically, construct and content validity, and reliability, with the same target population. Both studies analyzed differences in distress by gender, and the correlation between DISBIP-S and mood symptoms scales (YMRS y HAM-D). However, the first study addressed the association between bipolar disorder types I and II and predominant polarity, but did not perform regression analyses. Also, whereas the first study showed a pilot study aimed at obtaining a brief measure (15-item scale after an initial pool of 46 items), the current study was intended to verify its psychometric properties with a larger sample and also to assess convergent and discriminant validity by using additional instruments that assess similar constructs. Furthermore, this study goes beyond addressing the psychometric properties of the DISBIP-S, to analyze clinical and sociodemographic variables that may have a predictive role in the distress experienced by bipolar patients, using the validated scales and the other measures to test convergent and discriminant validity.

This study has several limitations that should be noted. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study prevented us from analysing the impact of distress along the life span. Second, participants were euthymic BD, so conclusions cannot be generalized to those patients who are not stabilized. Third, given the extension and number of the measures, some of them were only applied to half of the sample, so even though a randomized criterion was utilized, future studies should include larger samples to verify current findings.

ConclusionsThe DISBIP-S has shown highly satisfactory internal consistency and construct validity, as well as high convergent validity, since analyses showed high correlations with other measures related to distress. This scale can be used as a first step to develop interventions aimed at dealing with problematic personal beliefs and interpersonal sources of distress. Reducing distress experienced by bipolar disorder patients could help improve their quality of life and daily functioning.

Funding sourceThis research was not funded.

Conflicts of interestDr Montes has received grants from and served as consultant, advisor, or CME speaker for Almirall, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Ferrer, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Qualigen, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (CIBERSAM). The other authors have not conflicts of interest.

We would like to acknowledge each professional's contribution in suggesting potential candidates for inclusion in the study.