Mental, neurological, substance use, suicide, and related somatic disorders (MNSS, for the Spanish acronym) have a negative impact on the quality-of-life of people and the Mexican economy, but updated information is lacking. The objective of this work is to analyze the disability adjusted life years (DALYs) of the MNSS in Mexico by sex, age, state, and degree of marginalization between 1990 and 2019.

MethodsThe data and methodology of the «Global Burden of Disease Group» (GBD) are used. The GBD calculates DALYs as the sum of two components: years of life lost due to premature mortality (YLL) and years lived with disability (YLD). Likewise, the data on the degree of marginalization from the National Population Council in Mexico are used.

ResultsMNSS represented 16.3% of the disease burden in the Mexican population in 2019. The trend of the age-standardized rates of DALYs of the MNSS has increased little from 1990 to 2019. The highest increase has been for women. Mental (depression) and neurological (headache) disorders contribute the most to the disease burden among MNSS. In the interior of the country, Baja California Sur presented the highest increase in the period.

DiscussionThe results show a complex panorama of the MNSS and its subtypes by sex, age groups and territory. More resources are needed to improve mental health care.

There is broad evidence that mental, neurological, substance use, suicide and related somatic disorders have a negative impact on the quality of life of individuals and the economy of countries.1–3 However, developing countries such as Mexico generally do not have a contemporary and comprehensive picture of the evolution of the disease burden of these conditions, jointly and separately, by territories and population groups.

At present there is a tendency to combine the disease burden of mental, neurological, substance use, suicide and associated somatic conditions (MNSS) into a single category so as to understand, embrace and get the measure of the problems that these conditions cause in society.4 Because these conditions mainly affect people's quality of life, and not their mortality, the most appropriate way to measure their impact on society is through disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

The aim of this study is to use the MNSS category to present the updated and detailed picture of mental health disorders in Mexico in 2019, further differentiated by MNSS subtypes. The combined and separate historical trend of these conditions as measured by DALYs between 1990 and 2019 by age group and sex is shown, as well as the percentage change between the period of interest for the 32 states of the Mexican Republic. It is hoped that this information can serve as a basis for decision-makers to better allocate resources in this area.

Materials and methodsThis is a cross-sectional study that analyses the percentage change in DALYs of MNSS between 1990 and 2019. To do so, we make exhaustive use of the public databases generated by the Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) of the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool), which allows us to have a measurement of DALYs that is not reported by the Mexican government in its official statistics. The DALY is a useful measure to quantify and compare diseases, injuries and health risks due to loss of healthy life and time lived with disability that can help in public policy decisions on how they should prioritise and allocate resources. The methodology for estimating DALYs in the GBD study has been published elsewhere.5,6

DALYs are the sum of two components: years of life lost due to premature mortality (YLL) and years lived with disability (YLD). The GBD calculates DALYs by multiplying the number of deaths in each age group by the respective standard life expectancy for each age group, and DALYs as the prevalence of different sequelae of disease and injury multiplied by the disability weighting for that sequela. The weights used by the GBD can be found in other publications.7 The extensive use of DALYs to understand mental health problems allows going beyond the use of mortality statistics, especially in conditions that produce a lot of disability but few direct deaths, such as depression or anxiety disorders.

To present the burden of mental illness as a whole, the classification proposed by Vigo et al.4 is followed, which has already been used in other studies.8–10 The argument of these authors is that the burden of mental illness has been underestimated because it has been separated, by medical tradition, into three conditions related to mental disorders. The first is the arbitrary separation between mental and neurological disorders, even though it is known that conditions in these two categories show both brain and affective modifications. The second is that suicide is presented dissociated from mental disorders, even though its relationship to mental illness is well established. And the third is the exclusion of chronic pain, which has been linked to mental and neurological disorders, but is usually included in musculoskeletal disorders. The authors suggest that one third of the DALYs of symptoms associated with chronic pain disorders (neck and low back pain) and one half of other musculoskeletal pain should be included in the MNSS. Finally, substance use disorders are often presented separately and are not included in the usual calculations of the burden of mental disorders. This paper uses this classification and methodology for the calculation of MNSS suggested by Vigo et al.4 to present the epidemiological picture of these disorders in Mexico, with the most recent information from the GBD (2019). Table 1 in the Appendix shows the groups of disorders selected for this study from the GBD website, with their respective International Classification of Diseases version 10 codes. The interested reader can learn about the selection of options that were used to obtain the GBD database through the following link: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool?params=gbd-api-2019-permalink/88f556bc85a7666bdbebdc1ff5ac8559.

Number and rate per 100,000 of DALYsa for MNSS and MNSS-associated somatic symptoms. Total population and by sex, Mexico, 2019.

| Cause | 2019 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both sexes | Men | Women | ||||

| Number of AVAD (II 95%) | Rate of DALYs per 100,000a (II 95%) | Number of DALYs (II 95%) | Rate of DALYs per 100,000a (II 95%) | Number of DALYs (II 95%) | Rate of DALYs per 100,000a (II 95%) | |

| Neurological disorders | 1.609.786 (687.860 - 3.094.658) | 1.333,0 (578,3 - 2.560,4) | 676.728 (328.152 - 1.237.286) | 1.190,4 (581,0 - 2.202,7) | 933.057 (351.857 - 1.876.248) | 1.468,6 (563,3 - 2.950,5) |

| Alzheimer's and other dementias | 340.093 (136.449 - 794.405) | 330,1 (132,4 - 763,4) | 152.308 (60.002 - 361.912) | 326,1 (128,0 - 779,8) | 187.784 (76.119 - 443.956) | 333,3 (135,5 - 787,0) |

| Parkinson's disease | 83.537 (72.686 - 94.786) | 77,1 (66,9 - 87,5) | 48.750 (40.775 - 56.725) | 98,5 (82,6 - 114,4) | 34.787 (29.743 - 40.497) | 59,2 (50,5 - 68,8) |

| Idiopathic epilepsy | 331.861 (238.118 - 450.011) | 266,3 (190,9 - 360,1) | 169.767 (124.054 - 224.638) | 278,7 (203,2 - 366,9) | 162.094 (112.257 - 224.843) | 254,6 (175,9 - 352,3) |

| Headache disorders | 746.430 (155.131 - 1.619.398) | 572,7 (119,4 - 1.239,8) | 245.639 (55.108 - 519.900) | 388,5 (88,1 - 820,5) | 500.792 (97.872 - 1.104.604) | 746,0 (144,7 - 1.643,4) |

| Migraine | 674.048 (102.246 - 1.529.406) | 516,8 (79,0 - 1.172,6) | 215.992 (36.496 - 482.057) | 341,0 (58,5 - 759,6) | 458.055 (65.872 - 1.060.505) | 682,1 (97,9 - 1.579,9) |

| Tension headache | 72.383 (21.922 - 251.612) | 56,0 (16,8 - 194,9) | 29.646 (7.955 - 121.313) | 47,5 (12,7 - 191,3) | 42.736 (14.026 - 135.245) | 63,8 (20,7 - 203,6) |

| Other neurological disorders | 107.864 (85.476 - 136.057) | 86,8 (68,7 - 109,6) | 60.264 (48.213 - 74.110) | 98,7 (79,1 - 121,2) | 47.601 (35.866 - 62.347) | 75,5 (56,7 - 99,0) |

| Mental disorders | 2.137.251 (1.565.124 - 2.802.651) | 1.653,5 (1.210,7 - 2.171,4) | 865.143 (636.042 - 1.131.226) | 1.388,0 (1.021,4 - 1.811,5) | 1.272.108 (936.114 - 1.667.386) | 1.901,1 (1.398,8 - 2.490,6) |

| Schizophrenia | 237.982 (172.800 - 303.573) | 181,3 (131,7 - 230,8) | 118.919 (86.539 - 151.802) | 188,5 (136,6 - 239,7) | 119.063 (87.374 - 151.614) | 174,5 (128,0 - 221,6) |

| Depressive disorders | 814.932 (568.817 - 1.108.767) | 630,6 (441,2 - 856,4) | 260.234 (181.843 - 354.395) | 422,9 (295,7 - 575,6) | 554.698 (383.227 - 761.272) | 824,9 (571,5 - 1.130,7) |

| Major depressive disorder | 702.133 (480.473 - 970.650) | 543,5 (373,6 - 750,0) | 210.393 (143.882 - 288.415) | 342,9 (234,8 - 472,0) | 491.740 (335.388 - 682.256) | 731,5 (500,9 - 1.011,7) |

| Dysthymia | 112.799 (73.961 - 166.267) | 87,0 (57,0 - 128,3) | 49.841 (32.193 - 73.596) | 80,1 (51,7 - 118,3) | 62.958 (41.312 - 92.605) | 93,4 (61,4 - 137,5) |

| Bipolar disorder | 259.160 (158.584 - 396.724) | 197,7 (121,0 - 302,7) | 114.847 (70.843 - 177.799) | 181,1 (112,1 - 278,8) | 144.313 (88.067 - 221.111) | 213,6 (129,9 - 328,4) |

| Anxiety disorders | 433.545 (304.638 - 596.434) | 335,6 (235,4 - 459,0) | 150.631 (104.671 - 207.347) | 240,2 (167,4 - 331,0) | 282.914 (198.643 - 389.644) | 425,5 (299,7 - 585,3) |

| Eating disorder | 68.279 (41.872 - 102.745) | 51,6 (31,7 - 77,6) | 18.468 (11.185 - 27.797) | 28,5 (17,3 - 43,1) | 49.811 (30.236 - 75.298) | 73,8 (44,8 - 111,8) |

| Anorexia nerviosa | 15.561 (9.060 - 25.033) | 11,8 (6,9 - 19,0) | 4.153 (2.381 - 6.597) | 6,4 (3,7 - 10,1) | 11.408 (6.713 - 18.302) | 17,1 (10,1 - 27,5) |

| Bulimia nerviosa | 52.719 (30.243 - 84.053) | 39,8 (22,8 - 63,3) | 14.315 (8.249 - 22.539) | 22,2 (12,8 - 34,8) | 38.403 (22.414 - 61.568) | 56,7 (33,2 - 90,8) |

| Autistic spectrm disorders | 70.670 (46.195 - 102.007) | 56,8 (37,1 - 82,0) | 51.801 (33.826 - 74.878) | 84,5 (55,3 - 122,2) | 18.869 (12.348 - 27.702) | 29,8 (19,5 - 43,8) |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 17.182 (9.478 - 29.206) | 13,6 (7,5 - 23,2) | 12.662 (7.017 - 21.486) | 20,1 (11,2 - 34,2) | 4.520 (2.443 - 8.057) | 7,2 (3,9 - 12,7) |

| Behavioural disorder | 90.842 (51.481 - 143.453) | 73,6 (41,5 - 116,4) | 56.719 (32.821 - 88.575) | 90,6 (52,6 - 141,4) | 34.122 (19.012 - 54.978) | 56,1 (31,2 - 90,6) |

| Intellectual disability of idiopathic development | 16.421 (4.801 - 30.586) | 13,1 (3,8 - 24,4) | 8.220 (2.197 - 15.624) | 13,3 (3,5 - 25,3) | 8.201 (2.811 - 15.027) | 12,8 (4,4 - 23,6) |

| Other mental disorders | 128.238 (82.178 - 195.484) | 99,7 (64,0 - 151,6) | 72.641 (46.882 - 110.436) | 118,1 (76,2 - 179,6) | 55.597 (35.352 - 84.239) | 82,8 (52,9 - 125,2) |

| Substance consumption disorders | 502.092 (406.374 - 617.941) | 384,2 (311,3 - 472,5) | 382.394 (311.371 - 464.988) | 610,1 (497,9 - 741,6) | 119.698 (86.859 - 155.262) | 177,2 (128,7 - 229,8) |

| Alcohol consumption disorders | 335.447 (275.840 - 416.935) | 257,6 (212,0 - 319,9) | 288.144 (237.267 - 352.138) | 463,4 (382,3 - 565,9) | 47.303 (34.511 - 63.225) | 69,8 (50,9 - 93,1) |

| Drug consumption disorders | 166.645 (123.775 - 216.838) | 126,6 (93,9 - 164,3) | 94.250 (71.572 - 120.925) | 146,7 (111,3 - 187,1) | 72.395 (51.025 - 96.501) | 107,4 (75,7 - 143,1) |

| Opiate consumption disorders | 67.284 (47.168 - 91.144) | 51,5 (36,1 - 69,5) | 33.901 (24.299 - 45.123) | 53,4 (38,4 - 70,7) | 33.383 (22.318 - 46.499) | 49,5 (33,3 - 68,9) |

| Cocaine consumption disorders | 40.028 (28.343 - 55.210) | 30,3 (21,5 - 41,8) | 26.651 (19.312 - 36.217) | 41,2 (30,0 - 55,7) | 13.377 (8.879 - 19.755) | 19,9 (13,2 - 29,5) |

| Amphetamine consumption disorders | 17.438 (10.256 - 28.109) | 13,1 (7,7 - 21,1) | 8.895 (5.684 - 13.692) | 13,7 (8,8 - 21,0) | 8.543 (4.609 - 14.470) | 12,6 (6,8 - 21,4) |

| Cannabis consumption disorders | 7.593 (4.527 - 11.753) | 5,7 (3,4 - 8,9) | 5.051 (3.070 - 7.803) | 7,8 (4,7 - 12,0) | 2.543 (1.495 - 4.002) | 3,8 (2,2 - 5,9) |

| Other drug consumption disorders | 34.303 (23.618 - 47.947) | 26,0 (17,9 - 36,2) | 19.753 (13.652 - 27.265) | 30,6 (21,2 - 42,1) | 14.550 (9.519 - 20.859) | 21,6 (14,1 - 31,0) |

| Suicide | 405.088 (345.349 - 470.578) | 307,6 (262,3 - 357,0) | 330.452 (275.832 - 395.431) | 515,2 (430,0 - 616,3) | 74.635 (60.201 - 90.673) | 111,6 (90,2 - 135,3) |

| Suicide by firearm | 42.074 (32.810 - 70.644) | 32,1 (25,1 - 53,8) | 38.785 (29.443 - 67.521) | 61,3 (46,6 - 106,1) | 3.288 (2.629 - 4.033) | 4,9 (3,9 - 6,0) |

| Suicide by other specified means | 363.014 (308.485 - 422.485) | 275,4 (234,2 - 320,3) | 291.667 (241.815 - 351.648) | 453,9 (376,4 - 547,4) | 71.347 (57.534 - 86.598) | 106,8 (86,3 - 129,4) |

| MNSS-associated somatic symptoms | 869.299 (611.075 - 1.184.893) | 678,0 (477,7 - 921,7) | 325.758 (225.048 - 450.231) | 532,9 (370,5 - 734,5) | 543.542 (382.659 - 733.989) | 811,0 (571,9 - 1091,9) |

DALYs: Disability-adjusted life years; II: Uncertainty interval; MNSS: Mental, neurological, substance use, suicide and related somatic disorders.

Health and disease are closely related to indicators of social wealth/poverty. For an internal comparison of the degree of wealth/poverty in Mexico, it is useful to use the Marginalisation Index (MI) calculated by the National Population Council (CONAPO). The MI is a multidimensional measurement that enables states to be differentiated according to four dimensions: educational deprivation, inadequate housing, insufficient monetary income and population distribution. The MI is widely used and valid in Mexico.11 Higher MI values mean a higher level of combined vulnerability of the four dimensions. In order to know the current status of the MI with the MNSS, the 2015 data are used, which are the most updated and available for Mexico. Entities with MI are classified into categories of very low, low, medium, high and very high marginalisation. Subsequently, when the purpose is to find relationships, the DALY rate is ordered from highest to lowest by the types comprising the MNSS. In order to make the estimates between MI and DALYs comparable over time, data from the 2015 GBD were used.

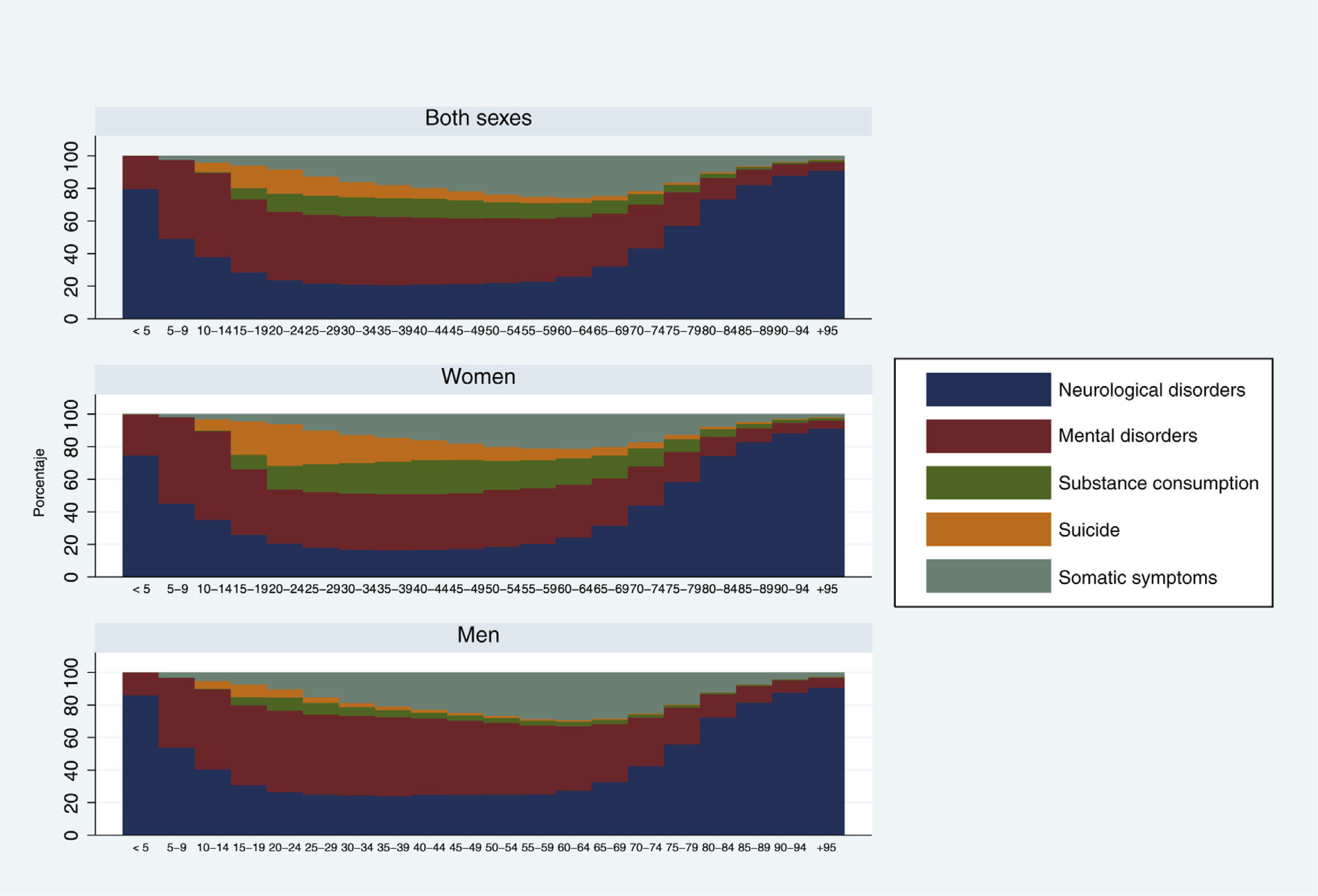

ResultsEstimates of the overall burden of disease for MNSS show that MNSS accounted for 16.3% of the total DALYs in Mexico in 2019 (Figure 1a). Of the major disease groups, MNSS are the second largest group for the total population and among women, but the third largest for men. DALYs for MNSS in women (18.8%) are higher than in men (14.1%). In 2019, in the total population, the group of mental disorders was the largest contributor to the total rate of DALYs in MNSS (38.7%), followed by neurological disorders (29.1%), MNSS-related somatic symptoms (15.7%), substance use (9.1%) and suicide (7.3%) (Fig. 1b). In women, after mental and neurological disorders, somatic symptoms are next in importance, while in men, substance use ranks third.

(a) Percentage contribution of DALYs from MNSS to all DALYs. Total population and by sex. Mexico, 2019. b) Percentage contribution of DALYs of those comprising MNSS to all DALYs of MNSS. Total population and by sex. Mexico, 2019.

DALYs: disability-adjusted life years; MNSS: mental, neurological, substance use, suicide and associated somatic disorders.

Source: Based on data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2020.

When analysing the number and rate of DALYs among the subtypes of the NSSM groups in the total population, the two highest are depressive disorders and headache disorders. Women, compared to men, have higher DALY rates in all subtypes of the disorder groups, except for substance use and suicide, where men have many more cases and a higher rate of DALYs than women (Table 1).

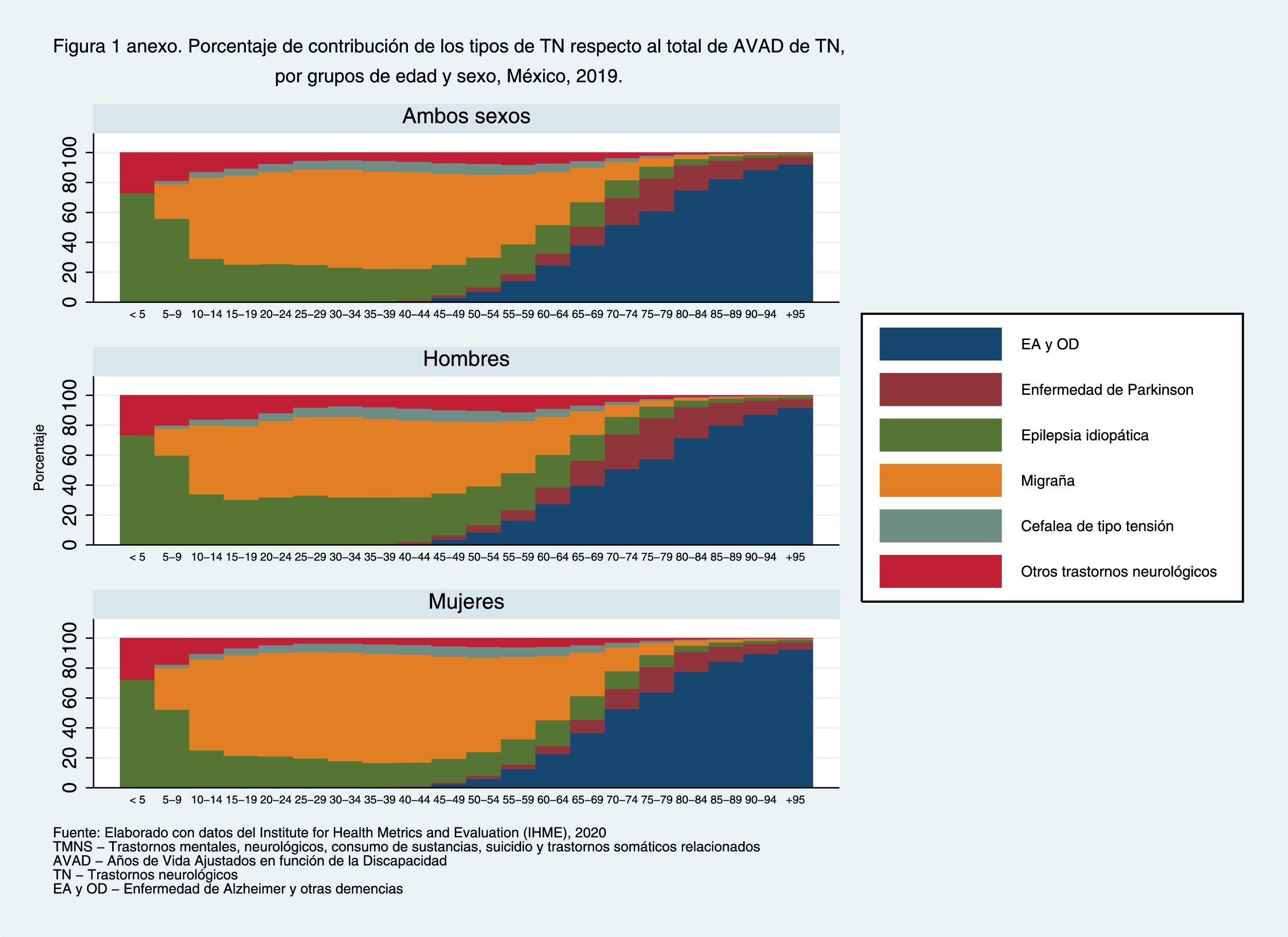

According to Figure 2, for both sexes, neurological disorders for children (0-9 years) and older adults (70 years and over) account for most of the MNSS. In children the major contribution comes from epilepsy and in older adults it is Alzheimer's disease and other dementias (Annex Figure 1). Mental disorders have a higher contribution to DALYs in the 10-64 years (Fig. 2) age group, mainly due to depressive disorders (Annex figure 2). Women have about 10% higher rate of DALYs for mental disorders compared to men in the 10-64 years age group. Next in importance are somatic symptoms associated with NSSM, which account on average for 25% of all NSSM in the 55-64 age group. Substance use disorder has a higher contribution to DALYs among 20-49 year olds with an average of 11.5% of total NSSM, mainly due to alcohol use (Annex Figure 3). In absolute terms men suffer almost three times the disease burden of substance disorders (Table 1), although in relative terms there are important differences between men and women in the type of substances most consumed, especially alcohol use in men and opiate use in women. Finally, suicides have a higher contribution to DALYs between the ages of 15 and 29, especially among men. The contribution of suicides by firearm is more common at older ages (Annex Figure 4).

Percentage contribution of MNSS types to total DALYs of MNSS, by age group and sex. Mexico, 2019.

DALYs: Disability-adjusted life years; MNSS: Mental, neurological, substance use, suicide and related somatic disorders.

Source: Based on data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2020.

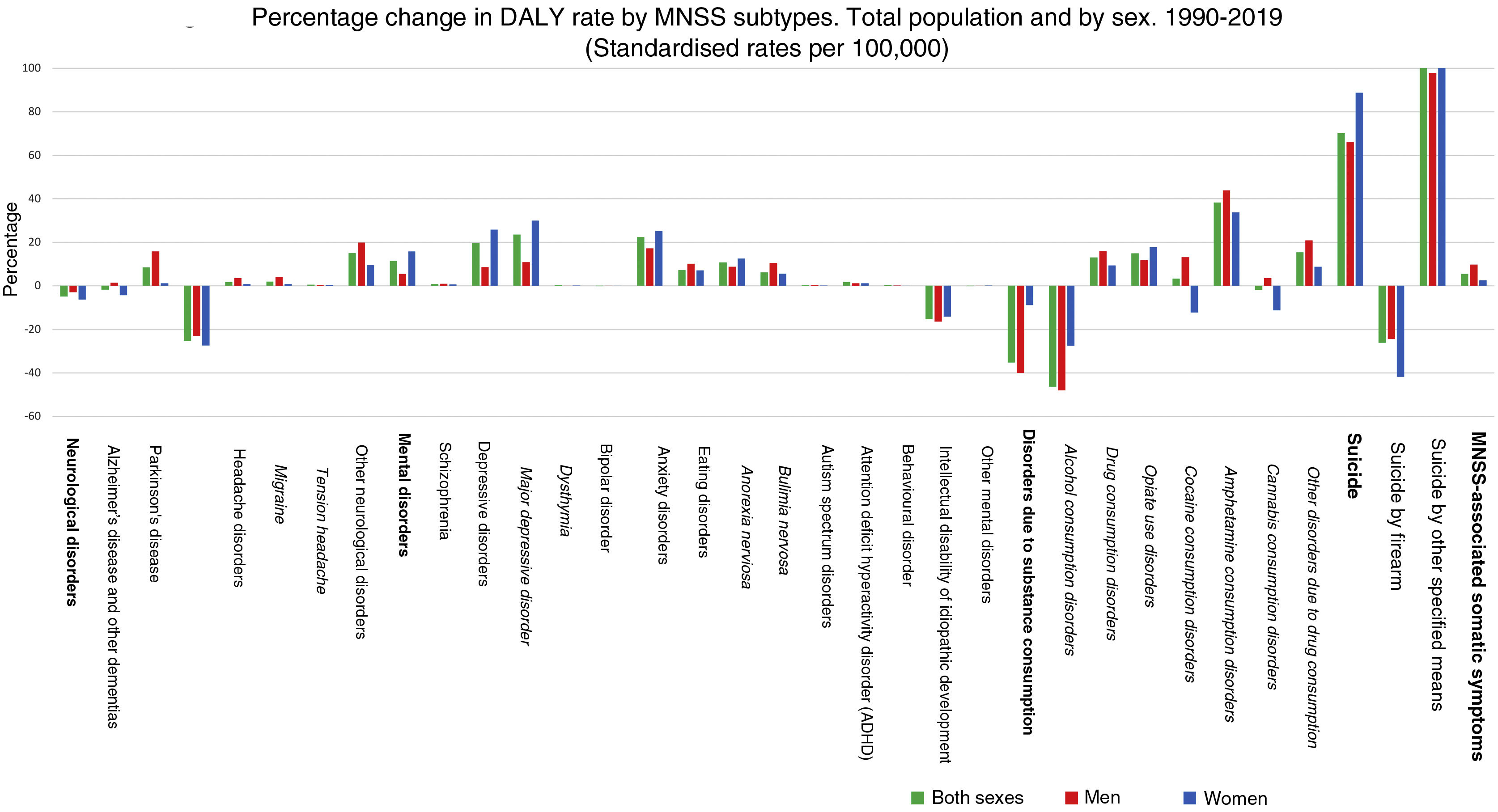

Figure 3 presents the percentage change in the rate of DALYs of MNSS between 1990 and 2019. The figure shows that, with the exception of substance use disorders (-35.2%) and neurological disorders (-4.9%), in the other three components of the NSSD there are increases for the total population. The largest increase is in the suicide group (70.2%) in both sexes, followed by mental disorders (11.4%) and somatic symptoms associated with MNSS (5.4%). It is interesting to note that the decrease in substance use disorders is almost exclusively due to decreases in alcohol use disorder, while for the other substances in general there are increases.

The highest percentage increase, by subtype, is observed for suicides by other means (100.8%) and depressive disorders (19.7%). In contrast, the largest percentage decreases were observed for alcohol use disorders (-46.4%), suicide by firearm (-26.2%) and epilepsy (-25.3%).

Overall, Alzheimer's disease and other dementias decreased (-1.8%) over the period, although it was women who showed the decrease (-4.3%), as men showed a slight increase in Alzheimer's disease (1.4%). Differences in trends, by sex, were also observed in cannabis use disorders (-1.8%) and cocaine use (3.3%), which shows a downward trend in women (-11.2% and -12.2%, respectively) while increasing in men (3.5% and 12.2%, respectively) (Fig. 3).

Percentage change in DALY rate by MNSS subtypes. Total population and by sex. 1990-2019 (Standardised rates per 100,000).

DALYs: Disability-adjusted life years; MNSS: Mental, neurological, substance use, suicide and related somatic disorders.

Source: Based on data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2020.

The country presents a mixed picture of changes in DALYs from 1990 to 2019 by state, with both increases and decreases. For the total population, the national percentage change in DALY rates over the period was only 1.3% (Figure 4). For both sexes, the state with the largest percentage increase in DALY change was Baja California Sur (8.0%), while the largest percentage decrease in DALY change was observed in Oaxaca (-8.3%). A more detailed analysis of these two states (data not shown) shows that, on the one hand, the increase in Baja California Sur was the result of an increase in mental disorders and suicide; on the other hand, a significant reduction in substance use and neurological disorders took place in Oaxaca.

National percentage change in the DALY rate in MNSS between 1990 and 2019.

The national percentage change in the DALY rate in NMSD between 1990 and 2019 for both sexes was 1.3%, for males it was -2.7% and for females it was 5.1%.

DALYs: Disability-adjusted life years; MNSS: Mental, neurological, substance use, suicide and related somatic disorders.

Source: Based on data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2020.

Two interesting differences by sex were found at the territorial level. First, the highest increase in MNSS over the period was observed for men in one state (Baja California Sur) in the north western part of the country, while women had the highest increase in three states in the southeast (Yucatan, Campeche and Quintana Roo) and one in the centre (Nayarit). Women have moderate increases in 18 Mexican states, while men only have moderate increases in four. Second, the most important decreases in the percentage change of MNSS in the period were found mainly in men for seven entities (Oaxaca, Veracruz, Tabasco, Puebla, Hidalgo, Tlaxcala and Querétaro) and only one in women (Oaxaca).

No relationship was found between the degree of marginalisation and the groups that make up the MNSS in the different states of the Mexican Republic (Figure 5). In the total population and among women, the order in the types of MNSS is the same for the first three places, regardless of the degree of marginalisation. In the male population, there is more variety in the order of MNSS within states. The exception is the state of Guerrero, which has a different behaviour from all states in the ranking of the types of MNSS. That is, among men, neurological disorders are the most important in Guerrero, followed by mental disorders, substance use, somatic symptoms associated with mental problems and finally suicide.

MNSS ordered by DALY rate per 100,000 in both sexes, males and females by marginalisation category and status. Age standardised. Mexico, 2015.

DALYs: Disability-adjusted life years; SUD: Substance use disorder; MNSS: mental, neurological, substance use and suicide disorders.

Source: Based on data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2020.

The aim of this study was to present a current and comprehensive picture of MNSS in Mexico from 1990 to 2019, using the most up-to-date data from the GBD. Among the main results, it was found that when considering mental health as a joint category measured by MNSS, MNSS show a high percentage (16.3%) of DALYs with respect to the total number of diseases and causes of death in Mexico. That is, approximately one out of every 6 years of healthy life lost in Mexico in 2019 comes from MNSS. Generally, epidemiological studies present the burden of mental illness in Mexico only from mental disorders or substance use disorders. However, if only these two categories were used, the share of mental disorders in DALYs would be only 7.5%. This new way of pooling all disorders related to mental health problems forms a better demonstration of the impact of related conditions on the overall DALYs in Mexico.

It was also found that there is a differential pattern by age in the burden of mental illness. In children under 9 years of age and in people aged 70 years and over, neurological disorders are the most relevant, while between 10 and 69 years of age, mental disorders are the most important. These findings are consistent with other research12–14 and are important for the development of public policies aimed at vulnerable groups that are more likely to suffer from some type of NSSM and less likely to have access to adequate services.

Results suggest the importance of recognising the weight of the burden of mental illness in Mexico, which as a whole is higher than what the Mexican government budgets for its care.10,15 Mental disorders increase in times of crisis. The past emergency situation of the 2017 earthquake showed that the country was not prepared to deal with the psychological aftermath of the event.16 The current COVID-19 pandemic impacts again on people's mental health and the government does not have sufficient resources to respond.17

There is a wide gap in the provision of MNSS services in Mexico, even above other Latin American countries.18 Although from 2000 to 2019 the “Seguro Popular” covered approximately 45% of the uninsured population for some MNSS (e.g. attention deficit disorder, eating disorders, addictions, depression, psychosis, epilepsy and seizures, Parkinson's disease and chronic pain)0,15,19 there is evidence that mental health services are scarce and underused by the Mexican population, especially those with low incomes.18 Studies on the use of mental health services in Mexican adults show that only 2 out of 10 people receive care,18 which is also common in the adolescent population.14 Attention deficit disorders,12 schizophrenia and depression are the most frequently requested.20 The most recent evaluation of the mental health system suggests a reduced and centralised infrastructure capacity in the country, as well as an over-concentration (80%) of the budget allocated for psychiatric hospitals and the rest for community care.21 The results show that MNSS have a very considerable weight in the burden of disease in Mexico and increased funding for MNSS-related problems is urgently needed.

LimitationsThe data used in this study have the limitations that have already been described in other GBD research on a global5,22 and national scale.23,24 Furthermore, the results presented are an approximation of the actual burden of disease. For example, the GBD does not calculate DALYs for any cause of death/morbidity according to co-morbidity,25 so the multiplied disability of MNSS when living with physical illness is unknown.26

Despite these limitations, this is the first study in Mexico to show in detail the burden of MNSS in the population over the last 30 years. Although a public policy of prevention, control and treatment of MNSS at national level is necessary, adaptations at state level are a next step. It is also clear from this presentation that specific policies need to be adapted, taking into account basic elements such as gender and age of the affected groups.

Transparency statementThe lead author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being presented, that no important aspects of the study have been omitted, and that differences from the study as originally planned have been explained.

AuthorshipJAGP originated the study, collected data, participated in data planning and analysis, wrote the initial draft and final version of the article. MLTO reviewed drafts and participated in writing the final version of the article. GB participated in data planning and analysis, made substantive contributions to the analysis and methods plan, and participated in writing the final version of the article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This research was conducted as part of the Global Burden of Disease, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD), coordinated by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. The GBD was partially funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; the sponsors had no role in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation, or report writing.