Depression usually worsens lifestyle habits, but previous evidence also suggests that an unhealthy lifestyle (UL) increases the risk of depression. Many studies have analyzed the association between lifestyle and depression in several nationally representative samples, but none have done so in the Spanish adult population. Our aim was to examine the associations between UL habits and depression in Spain.

Materials and methodsAnalysis of cross-sectional data from the latest National Health Survey published in 2018 (N=23,089). Data on depression and 4 lifestyle factors (diet, physical exercise, smoking, and alcohol consumption) were used. These factors were combined into an UL index ranging from 0 (healthiest lifestyle) to 4 (unhealthiest lifestyle). The prevalence of depression at different levels of the UL index, and the association between depression and both the cumulative UL index and the 4 UL factors was analyzed using parametric and non-parametric tests.

ResultsSedentarism was the most prevalent UL factor, followed by unhealthy diet, smoking and high-risk alcohol consumption. Having ≥1 UL factors was associated with a higher prevalence of depression compared to having 0 UL factors (2.5% vs. ≥5.2%), regardless of the cumulative number UL factors (1, 2, 3 or 4). Being physically inactive (OR=1.6) and a smoker (OR=1.3) increased the likelihood of depression. Being a high-risk wine drinker (OR=0.26) decreased the likelihood of depression. Dietary intake was not significant.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of depression changes depending on several modifiable lifestyle factors. Policy makers should therefore spare no resources in promoting strategies to encourage healthy lifestyles and prevent the acquisition of UL habits.

Depression is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide and has been associated with the most lethal and recurrent suicide attempts.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated a prevalence of 5.0% in the adult population.2 According to the European Health Interview Survey 2020, the prevalence in Spain is 5.4% being twice as high in women as in men (7.1% vs. 3.5%).3 However, the severity of depressive symptoms can change markedly in association with multiple biopsychosocial factors,4 of which lifestyle is one of the most important.5

There is growing evidence from cross-sectional and longitudinal studies that unhealthy behaviors are related to depression. Factors such as an unhealthy diet, sedentary lifestyle, smoking and high alcohol consumption have been associated with depression.6 These lifestyle factors have also been linked to physical illness. Indeed, patients with depression are more prone to diseases such as obesity and diabetes than non-depressed patients.5 This can lead to multimorbidity, which has been related to increased chronicity and mortality, as well as worse functionality and higher use of health services, posing a challenge for public care providers.7

Prior to 2020, depression was a leading cause of global health burden. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the urgency to strengthen public care providers by incorporating physical and mental health promotion strategies has increased.8,9 There is evidence that while unhealthy habits such as smoking and high alcohol consumption can increase the likelihood of illness or hinder the recovery process, a healthy lifestyle such as a balanced diet and being physically active has the potential to decrease the risk of disease or improve health.10 To date, several studies have focused on analyzing the impact of lifestyle factors separately11,12 and those examining their combined impact are scarce, especially in relation to mental disorders such as depression.6 Lifestyle factors are concomitant and interact with each other.5 Therefore, studying them in combination rather than individually can help us to approach depression from a more holistic and ecological perspective and to see the synergistic impact that the accumulation of different unhealthy habits has on it.

Recently, unhealthy lifestyle (UL) has started to be studied as a set of risk behaviors, which helps to understand their cumulative and synergic effect on health and disease. As far as we know, 8 cross-sectional studies13–20 and 8 longitudinal studies21–28 have used a combined index of at least three (un)healthy habits to analyze the relationship between lifestyle and depression. Of these, only those of the “Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra” (SUN) cohort have comprehensively and prospectively examined the relationship between lifestyle and depression in samples of Spanish individuals.25,28 However, these studies are limited to alumni (i.e., university graduates), so their results are not generalizable to other populations in Spain.

To our knowledge, no previous study has specifically examined the relationship between lifestyle and depression in a representative sample of the Spanish adult population. Therefore, the aim of this study was twofold: first, to define an index of unhealthy habits combining diet, physical exercise, tobacco use and excessive alcohol consumption; and second, to examine the association between this index of unhealthy behaviors and depression through the most recent data provided by the Spanish National Health Survey (SNHS).29 Consistent with previous research, we hypothesized: first, that the higher the number of unhealthy habits, the higher the intensity of the association with depression; and second, that an unhealthy diet, being physically inactive, being a smoker, and being a high-risk drinker will be more strongly associated with depression compared to having a healthy diet, being physically active, being a non-smoker, and being a low-risk drinker.

Material and methodsStudy designThis study is a cross-sectional data analysis of the latest SNHS published in 2018 and conducted by the Ministry of Health and the National Institute of Statistics.29 The aim of this survey is to provide health information related to the adult population in Spain. To this end, a representative sample of the Spanish adult population was assessed using a stratified sampling design between October 2016 and October 2017, ensuring that all seasons of the year were equally covered. From a total of 37,500 households distributed in 2500 census sections, one adult (≥15 years) per household was randomly selected to respond to the survey. The method of data collection was through a computer-assisted face-to-face interview conducted by trained interviewers. The final sample included 23,089 individuals.

Primary outcome measureThe primary outcome measure was depression assessed using the Spanish version of General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)30 and the following two items: “Have you had depression in the past 12 months?” and “Have you received a medical diagnosis of depression in the past 12 months?”.

The GHQ is a 12-item questionnaire used to assess psychological distress. Using the past month as a reference, participants responded whether they had experienced specific symptoms of psychological distress on a 4-point Likert scale (i.e., less than usual, no more than usual, rather more than usual, or much more than usual). Values 0-0-1-1 were assigned to each of the 4 possible responses per GHQ item, respectively, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 12. The higher the score, the higher the degree of psychological distress.31 Prioritizing the specificity of the questionnaire, we defined high levels of psychological distress as a score of ≥5.4

For the purposes of this study, depression was defined as having a score ≥5 on the GHQ and responding positively (i.e., “yes”) to the two individual items.

Lifestyle variablesWe focused on the following lifestyle factors: diet, physical activity, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption.

Diet was assessed by the type and frequency of unhealthy foods consumed regularly in a week based on the Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity Prevention Pyramid of the Spanish Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition (NPAOPP-SAFSN).32 Type of unhealthy foods included soft drinks with sugar, fast food (e.g., fried chicken, sandwiches, pizzas, hamburgers) and snacks (e.g., chips, crackers, cookies). Frequency of consumption was collected using a 6-point Likert scale (i.e., ≥1 times a day [5 points], 4–6 times a week [4 points], 3 times a week [3 points], once or twice a week [2 points], less than once a week [1 point] and never [0 points]). The higher the score, the unhealthier the diet.

Physical activity was determined by the frequency and duration of physical exercise performed in the last week assessed with The International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF)33 in its Spanish version.34 The IPAQ-SF records physical activity according to 4 levels of intensity (i.e., vigorous, moderate, walking, and sedentary) and 3 categories of activity (i.e., low/inactive, moderate, and high). Vigorous intensity refers to activities that produce a significant increase in breathing, heart rate and sweating for ≥10min. Moderate intensity refers to activities that require medium effort and cause breathing harder than normal for <10min. Category 1 (inactive) is the lowest level of activity and refers to those who do not meet the criteria for categories 2 and 3. Category 2 (moderate) is defined as ≥3 days of vigorous-intensity activity of at least 20min duration, ≥5 days of moderate-intensity activity or walking of at least 30min duration, or ≥5 days of any combination of walking, moderate-intensity, or vigorous-intensity activities, Finally, category 3 (high) is defined as ≥3 days of vigorous-intensity activity of at least 60min duration or ≥7 days of any combination of walking, moderate-intensity, or vigorous-intensity activities.

Tobacco use was measured by asking respondents whether they were smokers at the time of assessment, regardless of their smoking history.

Alcohol consumption was recorded by questions on the frequency and amount of alcohol (in glasses or standard drink units) consumed in the last week. Equivalences between alcoholic beverages and grams of alcohol can be found elsewhere.35

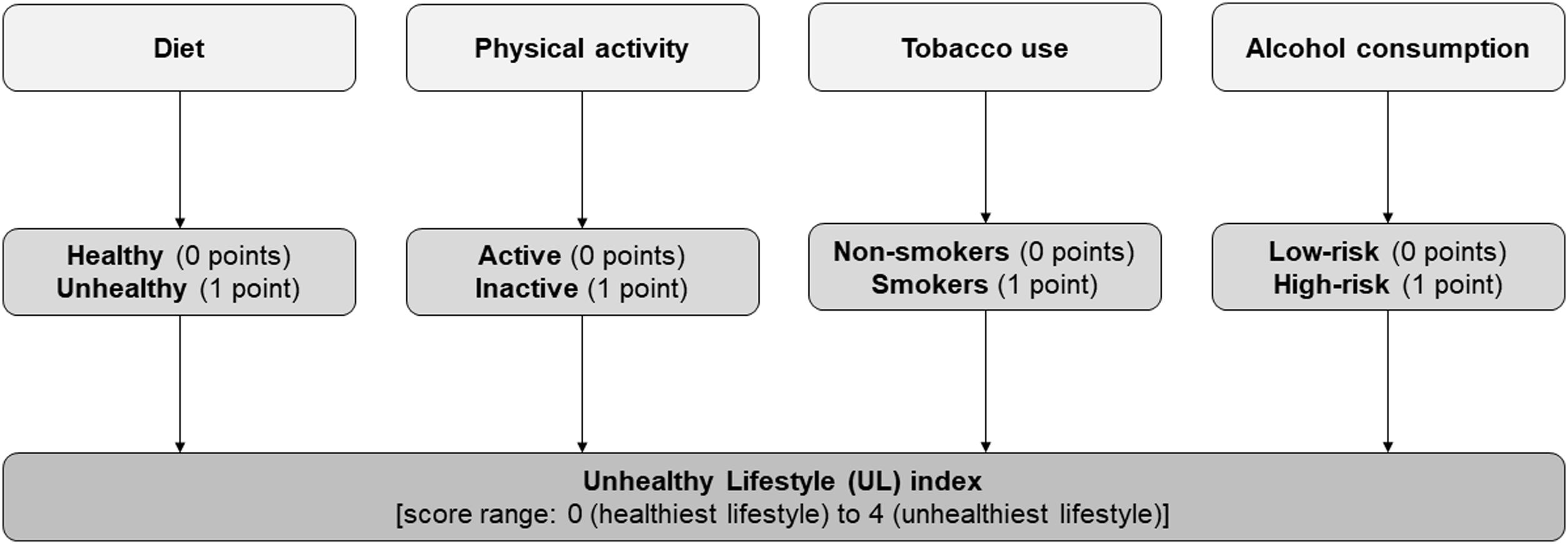

Unhealthy lifestyle indexAn own index of UL was build based on data from dietary intakes, physical activity, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption. As shown in Fig. 1, each of the 4 lifestyle factors was dichotomized into healthy (0 points) vs. unhealthy (1 point) behavior. For each UL factor, 1 point was added to the UL index up to a maximum of 4 points, so that the higher the score, the unhealthier the lifestyle.

Regarding dietary intake, the recommendations on the frequency of consumption of healthy and unhealthy foods from the NPAOPP-SAFSN were followed.32 It is advisable not to consume unhealthy foods, including soft drinks with sugar, fast food and/or snacks, more than occasionally and moderately (i.e., once or twice a week at most). Then, if participants had consumed any of these foods>3 times a week or the sum of the frequency of consumption of all of them was>6 points, they were classified as having an “unhealthy diet” (1 point). All other cases were classified as “healthy diet” (0 points).

In terms of physical activity and following WHO recommendations,36 adults should perform at least 150–300min of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, 75–150min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity, on a weekly basis. Muscle strengthening activities of moderate or higher intensity involving all major muscle groups ≥2 days per week are also recommended. Therefore, subjects in categories 2 and 3 of the IPAQ-SF, which is the moderate-high level of physical activity, were classified as a “physically active” individual (0 points), while those in category 1 were classified as a “physically inactive” individual (1 point).

The WHO does not recommend smoking at all.37 Therefore, being a “smoker” was classified as an unhealthy lifestyle (1 point) and being a “non-smoker” as a healthy lifestyle (0 points).

The Spanish Ministry of Health recommends that the maximum daily amount of low-risk alcohol consumption is ≤20g/day or 2 standard drinking units for men and ≤10g/day or 1 standard drinking unit for women.35 Then, if participants had exceeded the recommended weekly amount of alcohol (i.e., >140g/week for men or >70g/week for women) they were classified as “high-risk drinkers” (1 point). All other cases were classified as “low-risk drinkers” (0 points).

Other variablesAge, sex, level of education, marital status, perceived social support, body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), diabetes and being on antidepressant treatment were also collected. For the purposes of this study, level of education was dichotomized into “high” (>12 years) vs. “low” (≤12 years) and BMI into “obesity” (≥30 points) vs. “non-obesity” (<30 points). Finally, perceived social support was assessed with the Duke-UNC-11 Functional Social Support Scale,38 an 11-item questionnaire with a total score ranging from 11 to 55 in which higher scores indicate lower perceived social support. A cut-off point at the 15th percentile was chosen to categorize subjects as “low” (≥32 points) vs. “adequate” (<32 points) perceived social support.39

Statistical analysisAnalyses were performed using STATA v.17.0. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Descriptive data are shown as mean (standard deviation, SD) or frequency (%). To compare sociodemographic, lifestyle and health characteristics of the participants at different levels of the UL index, analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student's t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables were used. To compare the prevalence of depression at different levels of the UL index, Chi-square tests with and without Bonferroni correction were used. To examine the association between depression and the cumulative UL index (range 0–4) and between depression and the 4 UL factors (i.e., unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, smoking, and high-risk drinking), crude and adjusted logistic regression models were performed. In the adjusted models, age, sex, education, marital status, perceived social support, obesity, diabetes, and antidepressant treatment were controlled for. A subanalysis was performed differentiating each type of alcoholic beverage (i.e., beer, wine, vermouth, distilled drinks, and cider).

ResultsSample characteristicsThe mean age of the participants was 53.4 (±18.9) years, and 54.1% (n=12,494) were female, 25.8% (n=5946) had higher education, 54.1% (n=12,465) were married, 4.3% (n=984) reported low perception of social support, and 9.7% (n=1540) were taking antidepressants. The prevalence of depression was 4.5% (n=1034) and women were twice as likely to be depressed as men (6.0% vs. 2.7%). As for physical illness, 17.8% (n=3910) of participants had obesity and 9.8% (n=2266) had diabetes.

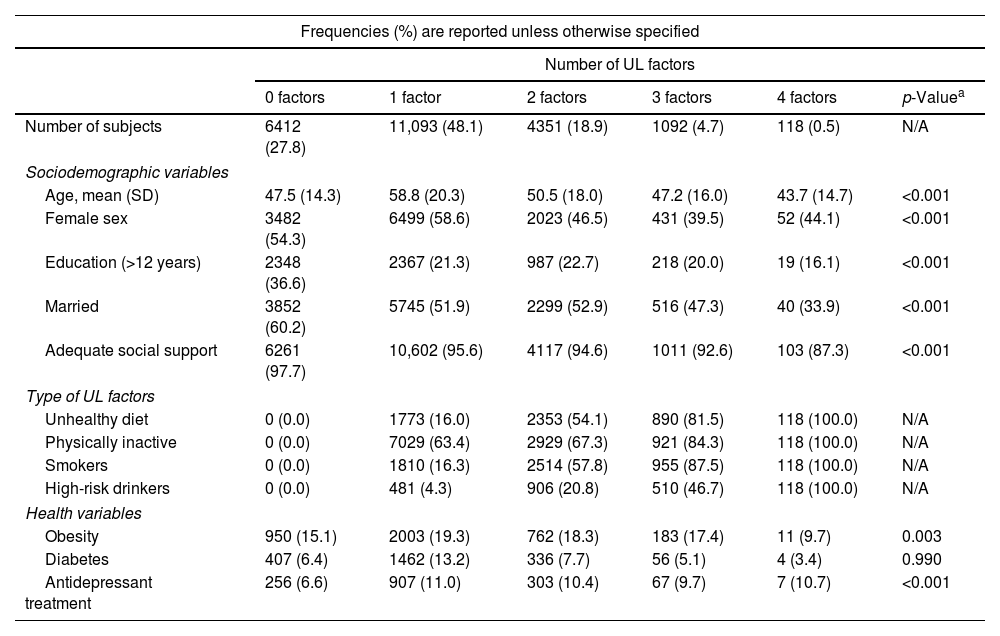

Unhealthy lifestyle dataOf the 23,089 participants included in the survey, information on the 4 lifestyle factors was available for 23,066 participants. Of these, 5134 (22.3%) had an unhealthy diet, 10,997 (47.7%) were physically inactive, 5397 (23.4%) were smokers, and 2015 (8.7%) were high-risk drinkers. The sociodemographic, lifestyle and health characteristics of the participants at the different levels of the UL index, except for the prevalence of depression, are shown in Table 1. Compared to those with 0 UL factors, participants with ≥1UL factors were older (47.5±14.3 vs. 55.7±19.9, p<0.001), less educated (>12 years: 36.6% vs. 21.6%, p<0.001), less likely to be married (60.2% vs. 51.7%, p<0.001), had a high proportion of individuals with perception of low social support (2.4% vs. 4.9%, p<0.001), were more prone to be depressed (2.5% vs. 5.2%, p<0.001), obese (15.1% vs. 18.8%, p<0.001) or diabetic (6.5% vs. 11.2%, p<0.001), and to be taking antidepressants (6.6% vs. 10.8%, p<0.001).

Characteristics of the sample at different levels of the unhealthy lifestyle (UL) index.

| Frequencies (%) are reported unless otherwise specified | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of UL factors | ||||||

| 0 factors | 1 factor | 2 factors | 3 factors | 4 factors | p-Valuea | |

| Number of subjects | 6412 (27.8) | 11,093 (48.1) | 4351 (18.9) | 1092 (4.7) | 118 (0.5) | N/A |

| Sociodemographic variables | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 47.5 (14.3) | 58.8 (20.3) | 50.5 (18.0) | 47.2 (16.0) | 43.7 (14.7) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 3482 (54.3) | 6499 (58.6) | 2023 (46.5) | 431 (39.5) | 52 (44.1) | <0.001 |

| Education (>12 years) | 2348 (36.6) | 2367 (21.3) | 987 (22.7) | 218 (20.0) | 19 (16.1) | <0.001 |

| Married | 3852 (60.2) | 5745 (51.9) | 2299 (52.9) | 516 (47.3) | 40 (33.9) | <0.001 |

| Adequate social support | 6261 (97.7) | 10,602 (95.6) | 4117 (94.6) | 1011 (92.6) | 103 (87.3) | <0.001 |

| Type of UL factors | ||||||

| Unhealthy diet | 0 (0.0) | 1773 (16.0) | 2353 (54.1) | 890 (81.5) | 118 (100.0) | N/A |

| Physically inactive | 0 (0.0) | 7029 (63.4) | 2929 (67.3) | 921 (84.3) | 118 (100.0) | N/A |

| Smokers | 0 (0.0) | 1810 (16.3) | 2514 (57.8) | 955 (87.5) | 118 (100.0) | N/A |

| High-risk drinkers | 0 (0.0) | 481 (4.3) | 906 (20.8) | 510 (46.7) | 118 (100.0) | N/A |

| Health variables | ||||||

| Obesity | 950 (15.1) | 2003 (19.3) | 762 (18.3) | 183 (17.4) | 11 (9.7) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes | 407 (6.4) | 1462 (13.2) | 336 (7.7) | 56 (5.1) | 4 (3.4) | 0.990 |

| Antidepressant treatment | 256 (6.6) | 907 (11.0) | 303 (10.4) | 67 (9.7) | 7 (10.7) | <0.001 |

SD, standard deviation; N/A, does not apply.

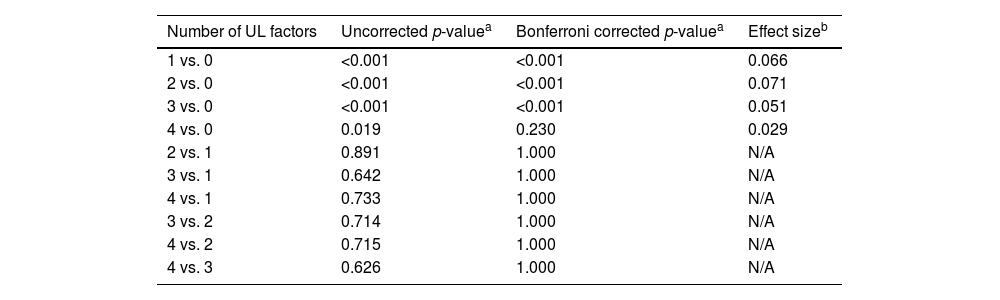

Of the 23,066 participants for whom information on the 4 lifestyle factors was available, data on depression were also available for 23,061 participants. The prevalence of depression at different levels of the UL index ranged from 2.5% (n=161/6411) of participants with 0 UL factors, 5.3% (n=585/11,092) of participants with 1 UL factor, 5.2% (n=227/4349) of participants with 2 UL factors, 5.0% (n=54/1092) of participants with 3 UL factors, and 6.0% (n=7/117) of participants with 4 UL factors (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). Table 2 shows that having 0UL factors was significantly associated with a lower prevalence of depression compared to having ≥1UL factors. No other significant differences in the prevalence of depression were found among the different levels of the UL index. These results were maintained after correcting for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method, except for the comparison between 0 and 4 UL factors. This non-significant result is probably due to differences in sample size between the groups.

Differences in the prevalence of depression among different levels of the unhealthy lifestyle (UL) index.

| Number of UL factors | Uncorrected p-valuea | Bonferroni corrected p-valuea | Effect sizeb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 vs. 0 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.066 |

| 2 vs. 0 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.071 |

| 3 vs. 0 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.051 |

| 4 vs. 0 | 0.019 | 0.230 | 0.029 |

| 2 vs. 1 | 0.891 | 1.000 | N/A |

| 3 vs. 1 | 0.642 | 1.000 | N/A |

| 4 vs. 1 | 0.733 | 1.000 | N/A |

| 3 vs. 2 | 0.714 | 1.000 | N/A |

| 4 vs. 2 | 0.715 | 1.000 | N/A |

| 4 vs. 3 | 0.626 | 1.000 | N/A |

N/A, does not apply.

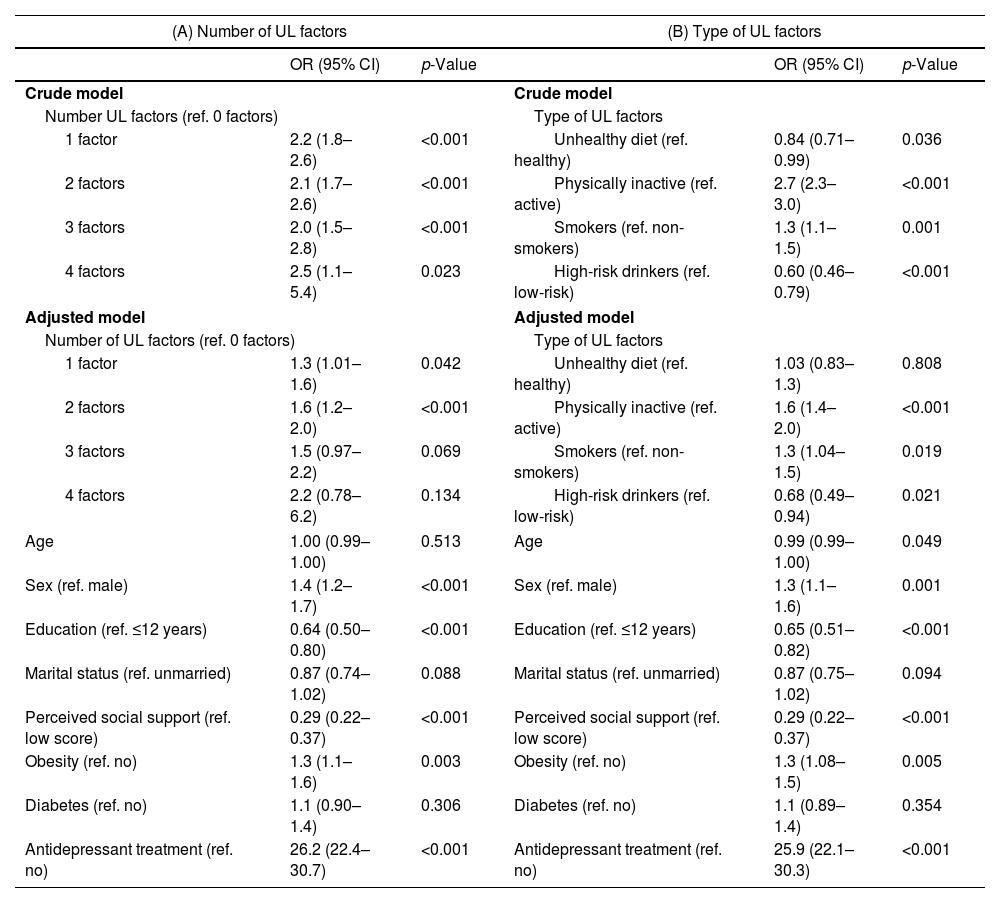

Table 3 (A) shows the crude and adjusted models for depression at different levels of the UL index. In the crude model, all participants with ≥1UL factors were more prone to be depressed compared with those in the lowest category (score of 0). After accounting for potential confounders, participants with 1 and 2UL factors were still more prone to be depressed compared with those in the lowest category, whereas participants with 3 UL factors showed a tendency to be more depressed compared with those in the lowest category. In contrast, the difference in the prevalence of depression among participants with 4 UL factors compared to participants with 0 UL factors did not reach statistical significance. As in Table 2, this non-significant result is probably due to differences in sample size between the groups.

Crude and adjusted models of the odds of depression according to the number and type of Unhealthy Lifestyle (UL) factors.

| (A) Number of UL factors | (B) Type of UL factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| Crude model | Crude model | ||||

| Number UL factors (ref. 0 factors) | Type of UL factors | ||||

| 1 factor | 2.2 (1.8–2.6) | <0.001 | Unhealthy diet (ref. healthy) | 0.84 (0.71–0.99) | 0.036 |

| 2 factors | 2.1 (1.7–2.6) | <0.001 | Physically inactive (ref. active) | 2.7 (2.3–3.0) | <0.001 |

| 3 factors | 2.0 (1.5–2.8) | <0.001 | Smokers (ref. non-smokers) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.001 |

| 4 factors | 2.5 (1.1–5.4) | 0.023 | High-risk drinkers (ref. low-risk) | 0.60 (0.46–0.79) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted model | Adjusted model | ||||

| Number of UL factors (ref. 0 factors) | Type of UL factors | ||||

| 1 factor | 1.3 (1.01–1.6) | 0.042 | Unhealthy diet (ref. healthy) | 1.03 (0.83–1.3) | 0.808 |

| 2 factors | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) | <0.001 | Physically inactive (ref. active) | 1.6 (1.4–2.0) | <0.001 |

| 3 factors | 1.5 (0.97–2.2) | 0.069 | Smokers (ref. non-smokers) | 1.3 (1.04–1.5) | 0.019 |

| 4 factors | 2.2 (0.78–6.2) | 0.134 | High-risk drinkers (ref. low-risk) | 0.68 (0.49–0.94) | 0.021 |

| Age | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.513 | Age | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.049 |

| Sex (ref. male) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | <0.001 | Sex (ref. male) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 0.001 |

| Education (ref. ≤12 years) | 0.64 (0.50–0.80) | <0.001 | Education (ref. ≤12 years) | 0.65 (0.51–0.82) | <0.001 |

| Marital status (ref. unmarried) | 0.87 (0.74–1.02) | 0.088 | Marital status (ref. unmarried) | 0.87 (0.75–1.02) | 0.094 |

| Perceived social support (ref. low score) | 0.29 (0.22–0.37) | <0.001 | Perceived social support (ref. low score) | 0.29 (0.22–0.37) | <0.001 |

| Obesity (ref. no) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 0.003 | Obesity (ref. no) | 1.3 (1.08–1.5) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes (ref. no) | 1.1 (0.90–1.4) | 0.306 | Diabetes (ref. no) | 1.1 (0.89–1.4) | 0.354 |

| Antidepressant treatment (ref. no) | 26.2 (22.4–30.7) | <0.001 | Antidepressant treatment (ref. no) | 25.9 (22.1–30.3) | <0.001 |

(A) Crude model: Pseudo R2=0.011, p<0.001; AUC=0.566 (0.551–0.581).

Adjusted model: Pseudo R2=0.312, p<0.001; AUC=0.864 (0.851–0.878).

(B) Crude model: Pseudo R2=0.029, p<0.001; AUC=0.633 (0.617–0.648).

Adjusted model: Pseudo R2=0.316, p<0.001; AUC=0.868 (0.854–0.881).

Table 3(B) shows the crude and adjusted models for depression according to the different factors of the UL index. In the crude model, physically inactive participants and smokers were more prone to be depressed compared to physically active participants and non-smokers, whereas participants with an unhealthy diet and high-risk drinkers were less prone to be depressed compared to participants with a healthy diet and low-risk drinkers. After accounting for potential confounders, physically inactive participants and smokers remained more prone to be depressed compared to physically active participants and non-smokers, high-risk drinkers remained less prone to be depressed compared to low-risk drinkers, and diet was no longer significant.

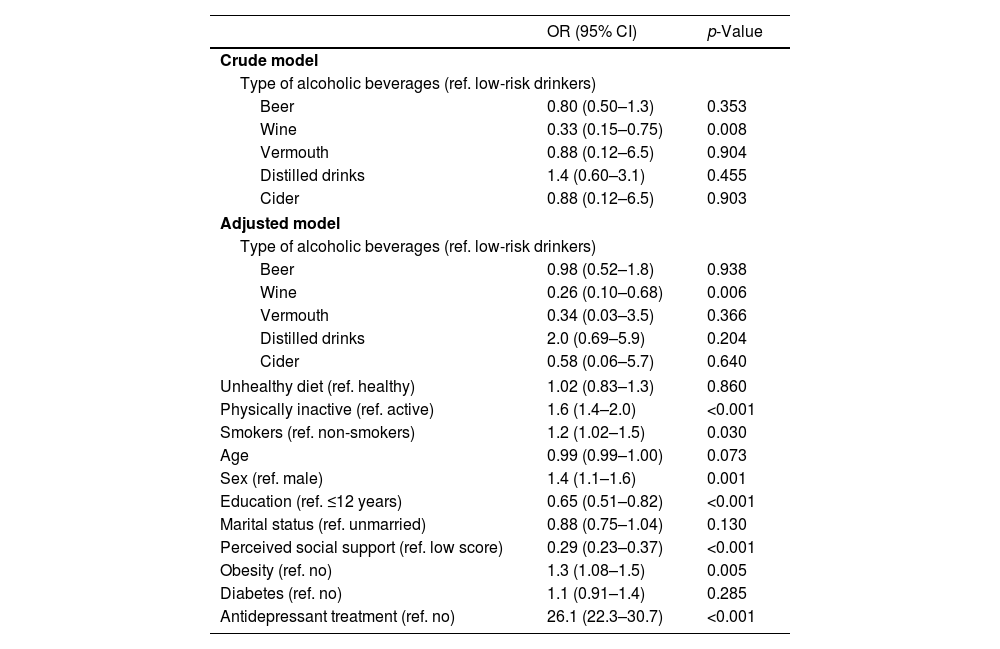

Associations between type of alcohol beverages and depressionSince high-risk drinking was significantly associated with a lower risk of depression, a subanalysis was performed differentiating each type of alcoholic beverage, including beer, wine, vermouth, distilled drinks, and cider (Table 4). In the crude model, only high-risk wine drinkers were less prone to be depressed compared with low-risk wine drinkers. This result was maintained after accounting for the other lifestyle factors (i.e., diet, physical activity, and smoking) and potential confounders. Consistent with Table 3(B), physically inactive participants and smokers remained more prone to be depressed compared to physically active participants and non-smokers, and diet was not significant.

Crude and adjusted models of the odds of depression according to type of alcoholic beverages.

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Crude model | ||

| Type of alcoholic beverages (ref. low-risk drinkers) | ||

| Beer | 0.80 (0.50–1.3) | 0.353 |

| Wine | 0.33 (0.15–0.75) | 0.008 |

| Vermouth | 0.88 (0.12–6.5) | 0.904 |

| Distilled drinks | 1.4 (0.60–3.1) | 0.455 |

| Cider | 0.88 (0.12–6.5) | 0.903 |

| Adjusted model | ||

| Type of alcoholic beverages (ref. low-risk drinkers) | ||

| Beer | 0.98 (0.52–1.8) | 0.938 |

| Wine | 0.26 (0.10–0.68) | 0.006 |

| Vermouth | 0.34 (0.03–3.5) | 0.366 |

| Distilled drinks | 2.0 (0.69–5.9) | 0.204 |

| Cider | 0.58 (0.06–5.7) | 0.640 |

| Unhealthy diet (ref. healthy) | 1.02 (0.83–1.3) | 0.860 |

| Physically inactive (ref. active) | 1.6 (1.4–2.0) | <0.001 |

| Smokers (ref. non-smokers) | 1.2 (1.02–1.5) | 0.030 |

| Age | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.073 |

| Sex (ref. male) | 1.4 (1.1–1.6) | 0.001 |

| Education (ref. ≤12 years) | 0.65 (0.51–0.82) | <0.001 |

| Marital status (ref. unmarried) | 0.88 (0.75–1.04) | 0.130 |

| Perceived social support (ref. low score) | 0.29 (0.23–0.37) | <0.001 |

| Obesity (ref. no) | 1.3 (1.08–1.5) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes (ref. no) | 1.1 (0.91–1.4) | 0.285 |

| Antidepressant treatment (ref. no) | 26.1 (22.3–30.7) | <0.001 |

Crude model: Pseudo R2=0.001, p=0.038; AUC=0.509 (0.504–0.514).

Adjusted model: Pseudo R2=0.317, p<0.001; AUC=0.871 (0.857–0.884).

Being younger, being female, having less education, having lower perceived social support, being obese, and being on antidepressant treatment were also significantly associated with depression. For more details, see Tables 3 and 4.

Finally, because of the strong association between antidepressant treatment and depression, we conducted an additional exploratory analysis in which antidepressant treatment was included in the definition of the dependent variable (depression) and not as a control variable in the logistic regression models, as has been done in previous studies.40 The results of this alternative approach complement and are consistent with the current approach and logistic regression models. Further details are provided in the supplementary material (see Fig. S2 and Tables S1–S3).

DiscussionTo our knowledge, this is the first study that has comprehensively examined the relationship between depression and a set of UL factors combining diet, physical activity, tobacco use and alcohol consumption in a representative sample of the Spanish adult population. Our results show that having ≥1UL factors appears to be associated with a higher prevalence of depression (≥5.2%) compared with having no UL factors (2.5%), regardless of the cumulative number of UL factors (1, 2, 3 or 4). While a sedentary lifestyle and being a smoker increased the likelihood of depression, being a high-risk wine drinker decreased the likelihood of depression. No significant relationship was found between dietary intake and depression.

In our study, 72.2% of participants exhibited ≥1 unhealthy behaviors. This is consistent with previous studies in other nationally representative samples13,15–17,21,23 and indicates that unhealthy habits are prevalent in the Spanish adult population as well. Half of the participants had a sedentary lifestyle, one in five had an unbalanced diet or were smokers, and one in ten consumed excessive alcohol. Compared to participants without UL factors, those with ≥1UL factors were older (mean age of 56 years), less educated (<12 years of schooling), less likely to be married, had a high proportion of individuals with perception of low social support, and were more prone to be depressed, obese, or diabetic. Therefore, individuals who meet these characteristics are the target population most likely to benefit from strategies aimed at modifying unhealthy habits. Several intervention programs have proven to be effective in modifying these behaviors.41,42 However, given that UL habits tend to be acquired at younger ages, usually during adolescence and early adulthood, it is at that time that campaigns aimed at mitigating or preventing their acquisition should be carried out.5

Consistent with our findings, a sedentary lifestyle is known to be associated with depression.43 Other studies analyzing data from different national surveys have also shown that being moderately inactive is related to depression.13,14,18–20,23,26,27 In fact, physically inactive people tend to spend less time in social and leisure activities, which may be related to less interest or pleasure in engaging in activities, which is a key symptom of depression.44 From this perspective, it could be argued that moderate- to high-intensity physical exercise may provide health benefits that may be helpful in reducing depression or promoting and maintaining remission.11,12,28,45 However, since the cross-sectional design of our study does not allow us to determine the direction of the association, research with longitudinal designs that address this question is needed. Moreover, this relationship should be further investigated, as the IPAQ-SF has some shortcomings due to its self-reported nature, such as overestimation by the participant of the amount of physical exercise performed or difficulties in distinguishing between theoretical concepts (e.g., between moderate- and vigorous-intensity physical exercise). In any case, the IPAQ-SF has good psychometric properties, has been validated in several countries and is widely used in international research studies, which gives value to our result.33

As has been shown in this and other studies analyzing data from different national surveys, being a smoker is significantly associated with depression.12–15,17,18,20,23,26,27 In fact, while smoking in the general population has decreased in recent years, among people with mental illness there has not been a marked decrease in tobacco use.46 A possible explanation is that the attempt to maintain a better mood may be a motivating factor for keep smoking among depressed individuals, which is a useful information for tailoring smoking cessation treatment programs for individuals exhibiting depressive symptoms.47 However, a recent systematic review of 148 studies that attempted to determine the causal relationship between smoking, depression and anxiety found inconsistent results as to the direction of the association, so further research is needed to draw definitive conclusions.48

Regarding alcohol consumption, we found that high-risk wine consumption, but not consumption of other types of alcoholic beverages (i.e., beer, vermouth, distilled drinks, and cider), decreased the likelihood of depression. Although the literature is controversial, there are studies showing a protective effect of moderate alcohol consumption against depression.27,49 In this regard, methodological differences in the estimation of alcohol intake between different countries and cultures could explain the reason for our result. While the WHO defines moderate alcohol consumption to be a daily intake of 41–60g in men and 21–40g in women,50 in our study we used the recommendations of the Spanish Ministry of Health,35 which, unlike those of the WHO, defines these amounts as high-risk consumption rather than moderate-risk consumption. Of particular interest is the “Prevention with Mediterranean Diet” (PREDIMED) study, which investigated the association between wine consumption and depression in 5505 Spanish people aged 55–80 years.51 The authors found that moderate wine consumption of 2–7 drinks per week was significantly associated with 32% lower risk of depression. Other studies have found that some wine components, such as polyphenols and their metabolites, could have a direct anti-inflammatory action on brain function by positively affecting pathways involved in stress-induced neuronal response,52 as well as an antidepressant-like effect,53 and that this is particularly evident in Mediterranean countries such as Spain, where moderate alcohol consumption, particularly of wine, is part of their culture.54 Finally, it should be noted that, compared to high-risk drinkers, people who drink alcohol in moderation may also have better physical health and more prosocial behaviors, both being negatively related to depression.55

Finally, similar to other studies,22,23,26 we found that dietary intake was not associated with depression. In this regard, it is worth mentioning that, although an association between diet and depression has been observed in some previous studies,14,17–21,24,25,27,28 to improve mental health it is more advisable to eat more fruits and vegetables (healthy foods) than to avoid fast food or soft drinks (unhealthy foods).56 In our study we only took into account unhealthy foods, so this methodological aspect may help explain why we did not find a relationship between dietary intake and depression. Interestingly, we did find a relationship between obesity and depression that had already been noted in previous studies.13,21 Other studies that have explored the impact of nutritional interventions in people with mood disorders point to an improvement in certain cognitive outcomes. Future studies should examine this in more detail.57

The large nationally representative sample of the Spanish adult population, the use of several measures of depression to ensure diagnostic specificity, and the design of a UL index based on previous literature give value to our results. However, our study is not without limitations. First, the results should be interpreted with caution because the survey from which we extracted the data was not specifically designed to test the objectives of this study. Second, some of the data collected were self-reported (e.g., IPAQ-SF and Duke-UNC-11 Functional Social Support Scale), so the results might change if objective measures had been used. Third, the cross-sectional design does not allow us to establish causal relationships between UL factors and depression, so more studies using different methodological approaches are needed. Fourth, tobacco use was defined very broadly compared to the other three aspects of UL, so these results should be interpreted with caution. Nicotine dependence may be a meaningful variable to consider in further studies.58–60 Finally, it is possible that variables not considered in our study, such as socioeconomic status and physical diseases other than obesity and diabetes, may be influencing the results.13,14,16,19,20,23 Future research should also take into account other lifestyle-related factors, such as hours of sleep, which previous studies have shown to be related to depression.20,24,25,27

ConclusionsIn summary, this study indicates that UL behaviors, in particular sedentary lifestyle, are highly prevalent in the Spanish adult population. Also that from a single UL factor there is already a higher prevalence of depression compared to having no UL habits, regardless of the cumulative number of UL factors. Therefore, public care providers should not spare resources in the prevention and modification of UL behaviors. Because the cross-sectional design of our study does not allow us to determine the direction of associations, future longitudinal studies are necessary to confirm our results. In any case, they may be useful to promote specific interventions aimed at modifying these behaviors in both healthy individuals and individuals with depression.

Authors’ contributionsMR and MG are the principal investigators and conceptualized the original study idea. PRS, VCS and GNV performed the statistical analysis. VCS, MGT and AC drafted the first version of the manuscript. GNV drafted the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation, critically reviewed the article for important intellectual content, approved the final version for publication, and were sufficiently involved in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate proportions of the content.

Ethical standardsThe authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Funding sourcesThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestMR received research funding from Lundbeck and Janssen not directly related to the publication of this study. The other authors have no conflicts of interest.