Negative symptoms (NS) include asociality, avolition, anhedonia, alogia, and blunted affect and are linked to poor prognosis. It has been suggested that they reflect two different factors: diminished expression (EXP) (blunted affect and alogia) and amotivation/pleasure (MAP) (anhedonia, avolition, asociality). The aim of this article was to examine potential sex differences among first-episode schizophrenia (FES) patients and analyze sex-related predictors of two NS symptoms factors (EXP and MAP) and functional outcome.

Material and methodsTwo hundred and twenty-three FES (71 females and 152 males) were included and evaluated at baseline, six-months and one-year. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to examine the effects of time and sex on NS and a multiple linear regression backward elimination was performed to predict NS factors (MAP-EXP) and functioning.

ResultsFemales showed fewer NS (p=0.031; Cohen's d=−0.312), especially those related to EXP (p=0.024; Cohen's d=−0.326) rather than MAP (p=0.086), than males. In both male and female group, worse premorbid adjustment and higher depressive symptoms made a significant contribution to the presence of higher deficits in EXP at one-year follow-up, while positive and depressive symptoms predicted alterations in MAP. Finally, in females, lower deficits in MAP and better premorbid adjustment predicted better functioning at one-year follow-up (R2=0.494; p<0.001), while only higher deficits in MAP predicted worse functioning in males (R2=0.088; p=0.012).

ConclusionsSlightly sex differences have been found in this study. Our results lead us to consider that early interventions of NS, especially those focusing on motivation and pleasure symptoms, could improve functional outcomes.

Schizophrenia is a complex and heterogeneous disorder with sex differences in clinical, functional and cognitive manifestations. Nevertheless, the nature of the relationship between sex-specific and clinical manifestations, cognitive impairment and functional outcome still remains unclear.1 The usual course of schizophrenia is marked by psychotic episodes with positive (delusions, hallucinations) and negative symptoms (apathy, social withdrawal, avolition) as well as cognitive impairment, which may result in the individual suffering a functional disability.2 The accomplishment of symptomatic and functional remission is one of the major objectives in early-stage interventions, as it is after presenting a first-episode of schizophrenia (FES).3 Although the majority of FES patients may show an improvement in their symptomatology after antipsychotic treatment, many continue to have long-term impairments in functioning.4 It has been well-demonstrated that interventions at early stages of the illness – that is, at the onset of FES – can improve subsequent outcomes. Thus, individuals with a first-episode of psychosis constitute a key group for studying the risk factors linked to the development of schizophrenia and other related disorders and its progression in terms of clinical outcome in later stages. Therefore, the early identification of clinical, functional and sociodemographic features may be important in identifying subsets of patients with similar characteristics, facilitating personalized treatment approaches from the early stages of the disease.

Negative symptoms have long been considered a core and independent dimension, distinct from other aspects of the illness (e.g., positive, cognitive and motor symptoms).5 This symptomatology is also highly predictive of poor psychosocial functional outcomes6 and largely contributes to the burden that the disorder poses on affected people, their relatives and society,7 suggesting it should be a key treatment target. Unfortunately, both pharmacological and psychosocial interventions for negative symptoms have demonstrated limited effectiveness. To address this critical unmet therapeutic need, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) sponsored a consensus development conference to delineate research priorities for the field and stimulate treatment development.8 One of the main conclusions of this meeting was the nature of this symptomatology; instead of categorizing it into a single category, it was suggested that the negative symptoms construct is multidimensional, comprising 5 discrete domains (anhedonia, avolition, asociality, blunted affect, alogia) with at least two correlated factors creating a hierarchical structure consisting of two higher-order dimensions: diminished expression (EXP) and amotivation and pleasure (MAP), that have more basic subordinate domains (EXP=blunted affect, alogia; MAP=anhedonia, avolition, asociality). Both factors may represent separable treatment targets with distinct etiologies.9,10 In this way, identifying specific dimensions that underline negative symptoms in early stages of schizophrenia could improve the understanding and the treatment of such invalidating symptomatology and its potential impact on the psychosocial functional outcome as well as progression of the illness.6

Related to sex-outcome differences in FES patients, studies have found mixed results.11 In schizophrenia and related disorders, sex differences have been observed in several clinical features; it has been well-demonstrated that the outcome of schizophrenia is poorer in male than in female patients.11,12 Compared to women, men tend to show a higher incidence of the disorder, an earlier age of onset, poorer premorbid adjustment, worse psychosocial functioning and a more severe course of the disease.12 Specifically, although not all the studies found differences, most of them found that regarding negative symptomatology, men have shown higher propensity to present these symptoms, especially in social withdrawal and blunted or incongruent affects than female patients, who presented more affective symptoms,13 and in alogia and avolition-apathy.14

The aims of the present study were (1) to explore sex differences among first-episode schizophrenia patients through one year follow-up focusing on different outcome measures as clinical, with a special focus on negative symptom dimensions, and psychosocial functioning, and (2) to analyze clinical predictors of negative dimensions and functional outcome, that is, motivation, pleasure, and expression.

Material and methodsSampleThe sample of this study has been recruited though the “2EPs Project”. It is a multicenter, coordinated, naturalistic, and longitudinal follow-up study of three years’ duration. “2EPs” included Spanish patients who met diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder with a first psychotic episode with less than five years of evolution. All the information about the methodology of the “2EPs Project” can be found elsewhere.15

The inclusion criteria were: (1) aged between 16 and 40 years at the first evaluation; (2) met diagnostic criteria according to DSM-IV for schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder; (3) ability to speak Spanish correctly; (4) signed informed consent; (5) have presented a first episode psychosis (FEP) in the last 5 years and are currently in remission according to Andreasen's criteria.3 According to this criteria, remission is achieved when the patient's Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) score is 3 or less (“mild” or better) in 8 items, as representative of an impairment level consistent with symptomatic remission of illness. There is also a minimum period of six months in which the symptoms severity must be maintained and the patient must not have relapsed after the episode. The exclusion criteria were: (1) having experienced a brain trauma with loss of consciousness; (2) an Intelligence Quotient (IQ) lower than 70 and with significant difficulties or malfunctioning with adaptive processes; and (3) somatic pathology with mental affectation.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and adhered to Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Ethics committees of all participating centers approved the current study. Each subject agreed to participate and signed the informed consent before their inclusion.

AssessmentsAt baseline, patients performed a complete evaluation that included: structured interviews, clinical scales and premorbid adjustment scales. Clinical and functional scales were also administered every three months for three years. In case of relapse, a visit was performed and the subject's participation in the study was terminated. For the current study, baseline, 6 months and one-year follow-up data was used (because a high percentage of subjects were lost to follow-up).

Sociodemographic, clinical and substance use assessmentSex, age and age at the onset of the illness were collected along with the duration of the untreated psychosis (DUP). DUP was calculated as the number of days between the first manifestations of psychotic symptoms and the initiation of adequate treatment for psychosis. Parental socioeconomic status (SES) was determined using Hollingshead's Two-Factor Index of Social Position.16 The diagnosis was confirmed using the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (SCID-I and II)17 or the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS)18 according to DSM-IV criteria. The participants at baseline were asked to report personal and family history of psychiatric disorders, namely affective and psychotic disorders. A psychopathological assessment was carried out with the Spanish versions of the following scales: maniac and depressive symptom severities were assessed using the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)19 and the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS),20 respectively; and positive, negative, and general symptoms were assessed by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).21 On each scale, the items were summed to obtain a total score. Higher scores indicate greater severity.

Although the PANSS is one of the most widely used measures of negative symptom severity, it has been well-demonstrated that it has several limitations; for instance, it was not designed to evaluate negative symptoms exclusively. Thus, we have also used the PANSS-Marder Factor Scores22 as it has more restrictive criteria to assess positive and negative symptomatology. The sum of the following items of the PANSS were used to calculate the Positive Symptom Factor (PSF): delusions (P1), hallucinatory behavior (P3), grandiosity (P5), suspiciousness/persecution (P6), stereotyped thinking (N7), somatic concerns (G1), unusual thought content (G9) and lack of judgment and insight (G12); and for the Negative Symptom Factor (NSF): blunted affect (N1), emotional withdrawal (N2), poor rapport (N3), passive/apathetic social withdrawal (N4), lack of spontaneity and conversation flow (N6), motor retardation (G7) and active social avoidance (G16). This structure has proved to be beneficial to obtain more specific information.23

As previously commented, the literature revealed the existence of two factors: EXP (diminished expression) and MAP (amotivation and pleasure).9,24 Following a previous work which used the PANSS,24 EXP factor was calculated as the sum of the following items of the PANSS: blunted affect (N1), poor rapport (N3), lack of spontaneity and conversation flow (N6) and motor retardation (G7), and MAP factor with emotional withdrawal (N2), passive/apathetic social withdrawal (N4) and active social avoidance (G16).24

Antipsychotic mean doses were collected and converted to chlorpromazine equivalents (CPZ) based on international consensus.25 Drug abuse was assessed using the adaptation of the multidimensional assessment tool European Addiction Severity Index (EuropAsi).26

Functional assessmentThe overall functional outcome was assessed by the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST)27 and the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF).28 Higher scores of FAST indicate greater disability, while higher scores on GAF correspond to better functioning.

Premorbid adjustment and cognitive reservePremorbid adjustment, namely levels of functioning before the onset of psychosis, was assessed with The Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS).29 The scale considers different life stages: childhood, early adolescence, late adolescence, and adulthood. Only childhood and early adolescence life periods have been taken into account since they were the two time periods for which the answers of all the participants were available. Higher scores indicate worse premorbid adjustment.

To assess cognitive reserve (CR) the three most commonly proposed proxy indicators of CR have been used30: (1) The estimated premorbid IQ was calculated with the vocabulary subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III).31 (2) Education was assessed taking into account the degree of schooling attained and passed by the subject. (3) Lifetime participation in leisure, social and physical activities was assessed with the PAS scale (scholastic performance) and the FAST scale, which allows us to assess specific life-domains such as interpersonal relationships and leisure time. When patients were assessed, they had already experienced a FES. For that reason, we could only estimate premorbid variables. To summarize the information of the three main proxies of CR, a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) was performed to create a “Composite CR score” for each subject. Higher scores correspond to better performance.

Data analysisDemographic, clinical and functional sex differences were examined using unpaired t-tests and Chi-square. A repeated measures ANOVA was used to examine the effects of time and sex on negative symptoms. To explore which variables could predict MAP, EXP or functioning at one-year follow-up three steps were undertaken: (1) Candidate exploratory variables were selected carefully taking into account their possible role in the prediction of negative symptom severity (focusing on total scores and on MAP and EXP factors separately) and functioning (GAF) at one-year follow-up. The potential predictors were: age, DUP, age at psychosis onset, socioeconomic status, personal and family psychiatric history, total scores of the PAS, cognitive reserve, Marder PANSS positive factor score (PSF), depressive symptoms (MADRS), psychosocial functioning (FAST), antipsychotic medication treatment, and alcohol, cannabis and/or tobacco consumption at baseline and lifetime cannabis use (all these variables from the baseline visit); (2) General Linear Model (GLM) Univariate Analysis was performed to explore whether predictors differ between sexes (interaction term between sex and each potential predictors); and (3) To explore which of these factors could predict general negative symptom severity and functioning at follow-up, significant predictors were included in a multiple linear regression model with backward elimination.

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS v25). All statistical tests were carried out two-tailed, with an alpha level of significance set at p≤0.05.

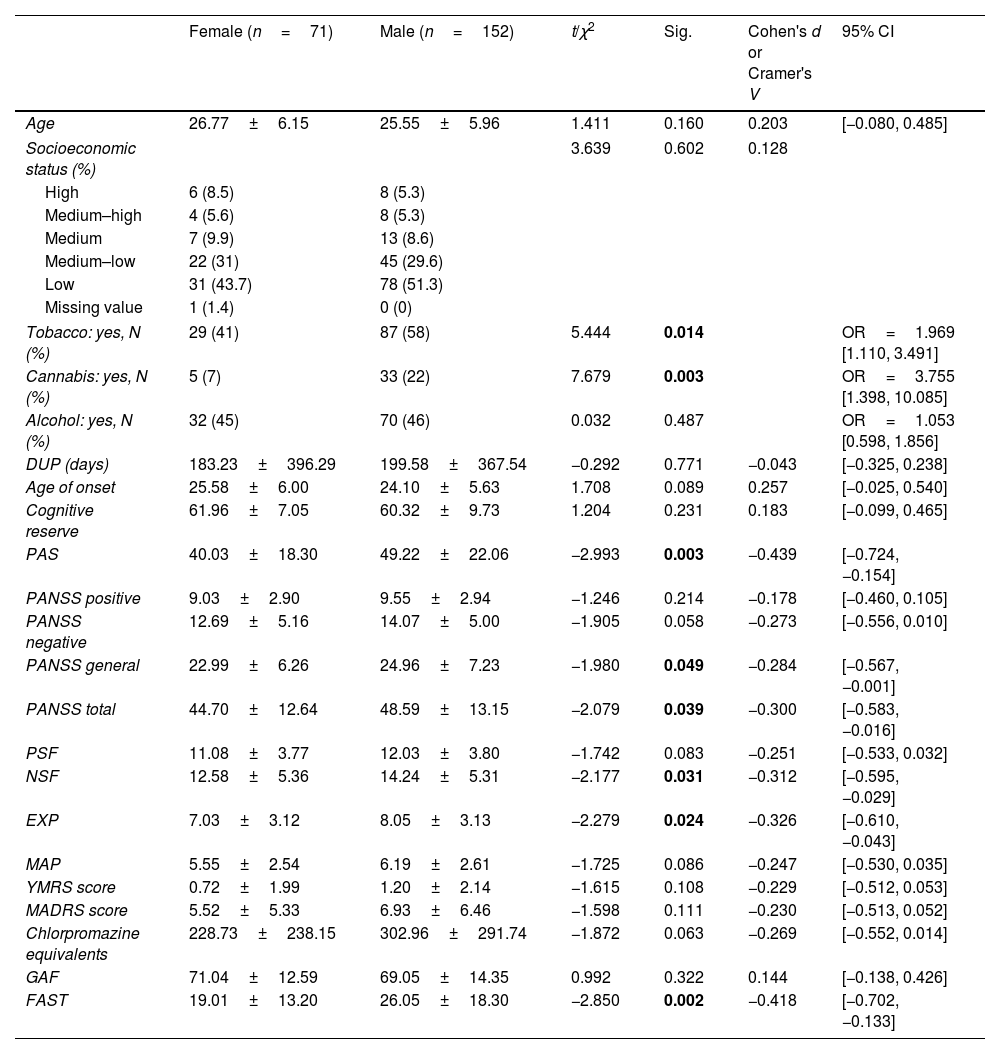

ResultsSociodemographic, clinical and functional characteristics of the sample and sex differencesOf the 223 FEP patients participating in the study, 31.8% (n=71) were females and 68.2% (n=152) were males. Mean age of onset was 26.77±6.15 years for female and 25.55±5.96 for male (p=0.160). The mean DUP time was 196.95 days (28 weeks approximately), without differences between females and males. Baseline sex differences in sociodemographic, clinical and functional characteristics are shown in Table 1. More males reported tobacco (p=0.014) and cannabis (p=0.003) use than females. Females showed a significantly lower severity of general and total symptoms according to the PANSS (p=0.049 and p=0.039), better premorbid adjustment (p=0.003) and greater functionality measured by the FAST scale (p=0.002), but not by the GAF (p=0.322). Women also showed fewer general negative symptoms than men, as measured by NSF (p=0.031, Cohen's d=−0.312; 95% CI=[−0.595, −0.029]), while there was only a tendency to signification in negative symptoms measured by the PANSS negative subscale (p=0.058). Finally, regarding dimensions specific to negative symptoms, females showed significantly less expressivity impairment (such as blunted affect or alogia) than males (p=0.024; Cohen's d=−0.326; 95% CI=[−0.610, −0.043]), without differences in motivation and pleasure disablement (e.g. anhedonia, avolition or asociality) (p=0.086). There were no differences between sex groups in terms of age, SES, age of onset, alcohol use, positive, manic and depressive symptoms, cognitive reserve and chlorpromazine equivalents.

Sex differences in sociodemographic, clinical and functional characteristics at baseline.

| Female (n=71) | Male (n=152) | t/χ2 | Sig. | Cohen's d or Cramer's V | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 26.77±6.15 | 25.55±5.96 | 1.411 | 0.160 | 0.203 | [−0.080, 0.485] |

| Socioeconomic status (%) | 3.639 | 0.602 | 0.128 | |||

| High | 6 (8.5) | 8 (5.3) | ||||

| Medium–high | 4 (5.6) | 8 (5.3) | ||||

| Medium | 7 (9.9) | 13 (8.6) | ||||

| Medium–low | 22 (31) | 45 (29.6) | ||||

| Low | 31 (43.7) | 78 (51.3) | ||||

| Missing value | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Tobacco: yes, N (%) | 29 (41) | 87 (58) | 5.444 | 0.014 | OR=1.969 [1.110, 3.491] | |

| Cannabis: yes, N (%) | 5 (7) | 33 (22) | 7.679 | 0.003 | OR=3.755 [1.398, 10.085] | |

| Alcohol: yes, N (%) | 32 (45) | 70 (46) | 0.032 | 0.487 | OR=1.053 [0.598, 1.856] | |

| DUP (days) | 183.23±396.29 | 199.58±367.54 | −0.292 | 0.771 | −0.043 | [−0.325, 0.238] |

| Age of onset | 25.58±6.00 | 24.10±5.63 | 1.708 | 0.089 | 0.257 | [−0.025, 0.540] |

| Cognitive reserve | 61.96±7.05 | 60.32±9.73 | 1.204 | 0.231 | 0.183 | [−0.099, 0.465] |

| PAS | 40.03±18.30 | 49.22±22.06 | −2.993 | 0.003 | −0.439 | [−0.724, −0.154] |

| PANSS positive | 9.03±2.90 | 9.55±2.94 | −1.246 | 0.214 | −0.178 | [−0.460, 0.105] |

| PANSS negative | 12.69±5.16 | 14.07±5.00 | −1.905 | 0.058 | −0.273 | [−0.556, 0.010] |

| PANSS general | 22.99±6.26 | 24.96±7.23 | −1.980 | 0.049 | −0.284 | [−0.567, −0.001] |

| PANSS total | 44.70±12.64 | 48.59±13.15 | −2.079 | 0.039 | −0.300 | [−0.583, −0.016] |

| PSF | 11.08±3.77 | 12.03±3.80 | −1.742 | 0.083 | −0.251 | [−0.533, 0.032] |

| NSF | 12.58±5.36 | 14.24±5.31 | −2.177 | 0.031 | −0.312 | [−0.595, −0.029] |

| EXP | 7.03±3.12 | 8.05±3.13 | −2.279 | 0.024 | −0.326 | [−0.610, −0.043] |

| MAP | 5.55±2.54 | 6.19±2.61 | −1.725 | 0.086 | −0.247 | [−0.530, 0.035] |

| YMRS score | 0.72±1.99 | 1.20±2.14 | −1.615 | 0.108 | −0.229 | [−0.512, 0.053] |

| MADRS score | 5.52±5.33 | 6.93±6.46 | −1.598 | 0.111 | −0.230 | [−0.513, 0.052] |

| Chlorpromazine equivalents | 228.73±238.15 | 302.96±291.74 | −1.872 | 0.063 | −0.269 | [−0.552, 0.014] |

| GAF | 71.04±12.59 | 69.05±14.35 | 0.992 | 0.322 | 0.144 | [−0.138, 0.426] |

| FAST | 19.01±13.20 | 26.05±18.30 | −2.850 | 0.002 | −0.418 | [−0.702, −0.133] |

Abbreviations: DUP=Duration of Untreated Psychosis; PAS=Premorbid Adjustment Scale; PANSS=Positive and Negative Symptom Scale; PSF=Positive Symptoms Factor of the PANSS; NSF=Negative Symptoms Factor of the PANSS; EXP=diminished expression; MAP=amotivation and pleasure; YMRS=Young Mania Rating Scale; MADRS=Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale; GAF=Global Assessment of Functioning; FAST=Functioning Assessment Short Test. Significant differences (p<0.05) marked in bold.

Those patients who were assessed at follow-up (n=120) were indistinguishable from those who were not (n=103) in terms of sex, sociodemographic, clinical and functional characteristics, except for positive symptoms measured by PSF (p=0.045, Cohen's d=0.275; 95% CI=[0.025, −2.064]), but not when they were measured by the PANSS positive subscale (p=0.108). For more details, see Supplementary Table 1.

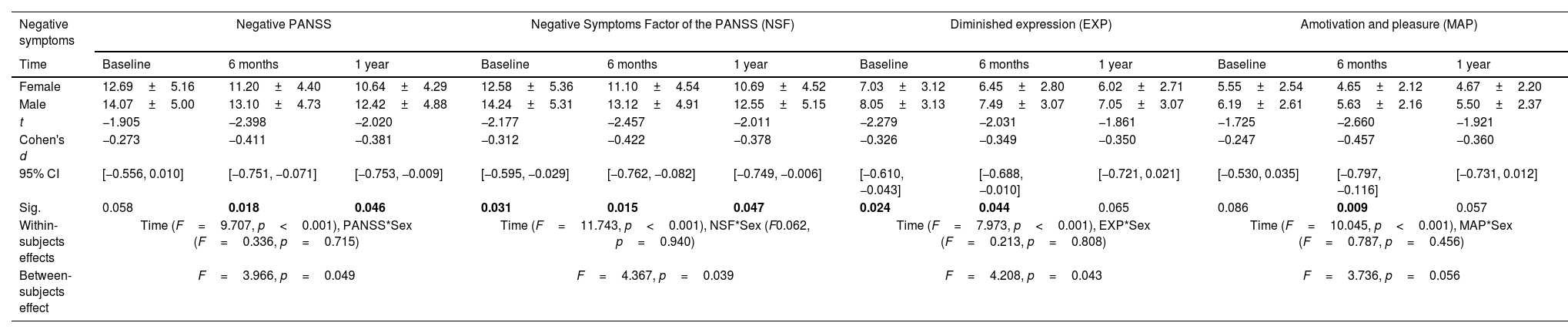

Sex differences in negative symptoms courseOf the 71 females assessed at baseline, 51 were assessed at 6 months and 45 at one-year follow-up. 152 males were assessed at baseline, 101 at 6 months and 75 at one-year follow-up. The repeated measures ANOVA results indicate that the mean scores for negative symptoms were significantly different across time points for PANSS (p<0.001, ηp2=0.118), NSF (p<0.001, ηp2=0.140), EXP (p<0.001, ηp2=0.117) and MAP (p<0.001, ηp2=0.118), with follow-up scores being significantly lower than baseline (see Table 2). However, no significant interaction of time and sex was found. Thus, there were significant time effects on all variables, indicating an improvement for both sexes, with no difference between them.

Sex differences in negative symptoms course.

| Negative symptoms | Negative PANSS | Negative Symptoms Factor of the PANSS (NSF) | Diminished expression (EXP) | Amotivation and pleasure (MAP) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Baseline | 6 months | 1 year | Baseline | 6 months | 1 year | Baseline | 6 months | 1 year | Baseline | 6 months | 1 year |

| Female | 12.69±5.16 | 11.20±4.40 | 10.64±4.29 | 12.58±5.36 | 11.10±4.54 | 10.69±4.52 | 7.03±3.12 | 6.45±2.80 | 6.02±2.71 | 5.55±2.54 | 4.65±2.12 | 4.67±2.20 |

| Male | 14.07±5.00 | 13.10±4.73 | 12.42±4.88 | 14.24±5.31 | 13.12±4.91 | 12.55±5.15 | 8.05±3.13 | 7.49±3.07 | 7.05±3.07 | 6.19±2.61 | 5.63±2.16 | 5.50±2.37 |

| t | −1.905 | −2.398 | −2.020 | −2.177 | −2.457 | −2.011 | −2.279 | −2.031 | −1.861 | −1.725 | −2.660 | −1.921 |

| Cohen's d | −0.273 | −0.411 | −0.381 | −0.312 | −0.422 | −0.378 | −0.326 | −0.349 | −0.350 | −0.247 | −0.457 | −0.360 |

| 95% CI | [−0.556, 0.010] | [−0.751, −0.071] | [−0.753, −0.009] | [−0.595, −0.029] | [−0.762, −0.082] | [−0.749, −0.006] | [−0.610, −0.043] | [−0.688, −0.010] | [−0.721, 0.021] | [−0.530, 0.035] | [−0.797, −0.116] | [−0.731, 0.012] |

| Sig. | 0.058 | 0.018 | 0.046 | 0.031 | 0.015 | 0.047 | 0.024 | 0.044 | 0.065 | 0.086 | 0.009 | 0.057 |

| Within-subjects effects | Time (F=9.707, p<0.001), PANSS*Sex (F=0.336, p=0.715) | Time (F=11.743, p<0.001), NSF*Sex (F0.062, p=0.940) | Time (F=7.973, p<0.001), EXP*Sex (F=0.213, p=0.808) | Time (F=10.045, p<0.001), MAP*Sex (F=0.787, p=0.456) | ||||||||

| Between-subjects effect | F=3.966, p=0.049 | F=4.367, p=0.039 | F=4.208, p=0.043 | F=3.736, p=0.056 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: PANSS=Positive and Negative Symptom Scale. Significant differences (p<0.05) marked in bold.

The baseline predictors of EXP at one-year follow-up with an interaction by sex were: family psychiatric history, PAS, PSF, MADRS, FAST and alcohol consumption (see Supplementary Table 2 for more details). The predictors of MAP were PSF, MADRS, FAST, tobacco use and alcohol consumption.

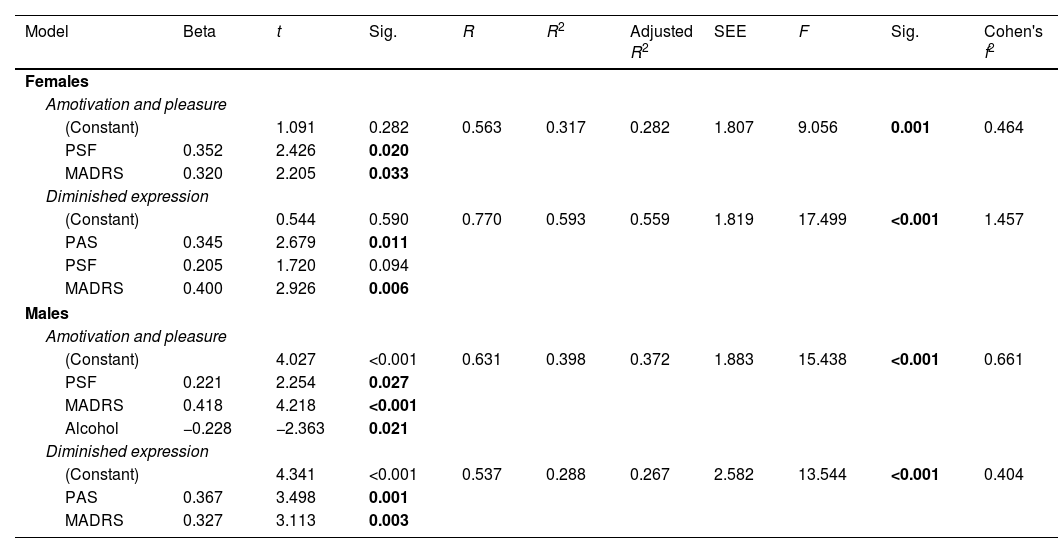

Predictors of EXP and MAP in females and males are shown in Table 3. Regarding females, premorbid adjustment (t=2.679, p=0.011), and depressive symptoms (t=2.926, p=0.006) at baseline made a significant contribution to the presence of higher deficits in expressivity at one-year follow-up (F=17.499, R2=0.593, p<0.001). Positive (t=2.426, p=0.020) and depressive (t=2.205, p=0.033) symptoms predicted deficits in motivation and pleasure at one-year follow-up (F=9.056, R2=0.317, p=0.001). In males, worse premorbid adjustment (t=3.498, p=0.001), and higher depressive symptoms (t=3.113, p=0.003) at baseline predicted higher deficits in expression at one-year follow-up (F=13.544, R2=0.288, p<0.001). Finally, positive (t=2.254, p=0.027) and depressive (t=4.218, p<0.001) symptoms and alcohol consumption (t=−2.363, p=0.021) at baseline predicted greater amotivation at one-year follow-up (F=15.438, R2=0.398, p<0.001).

Linear regression models for predictors of Motivation and Pleasure and Diminished expression at one-year follow-up in females and males.

| Model | Beta | t | Sig. | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | SEE | F | Sig. | Cohen's f2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | ||||||||||

| Amotivation and pleasure | ||||||||||

| (Constant) | 1.091 | 0.282 | 0.563 | 0.317 | 0.282 | 1.807 | 9.056 | 0.001 | 0.464 | |

| PSF | 0.352 | 2.426 | 0.020 | |||||||

| MADRS | 0.320 | 2.205 | 0.033 | |||||||

| Diminished expression | ||||||||||

| (Constant) | 0.544 | 0.590 | 0.770 | 0.593 | 0.559 | 1.819 | 17.499 | <0.001 | 1.457 | |

| PAS | 0.345 | 2.679 | 0.011 | |||||||

| PSF | 0.205 | 1.720 | 0.094 | |||||||

| MADRS | 0.400 | 2.926 | 0.006 | |||||||

| Males | ||||||||||

| Amotivation and pleasure | ||||||||||

| (Constant) | 4.027 | <0.001 | 0.631 | 0.398 | 0.372 | 1.883 | 15.438 | <0.001 | 0.661 | |

| PSF | 0.221 | 2.254 | 0.027 | |||||||

| MADRS | 0.418 | 4.218 | <0.001 | |||||||

| Alcohol | −0.228 | −2.363 | 0.021 | |||||||

| Diminished expression | ||||||||||

| (Constant) | 4.341 | <0.001 | 0.537 | 0.288 | 0.267 | 2.582 | 13.544 | <0.001 | 0.404 | |

| PAS | 0.367 | 3.498 | 0.001 | |||||||

| MADRS | 0.327 | 3.113 | 0.003 | |||||||

Abbreviations: SEE=standard errors of the estimates; PAS=Premorbid Adjustment Scale; PSF=Positive Symptoms Factor of the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale; MADRS=Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale. Significant differences (p<0.05) marked in bold.

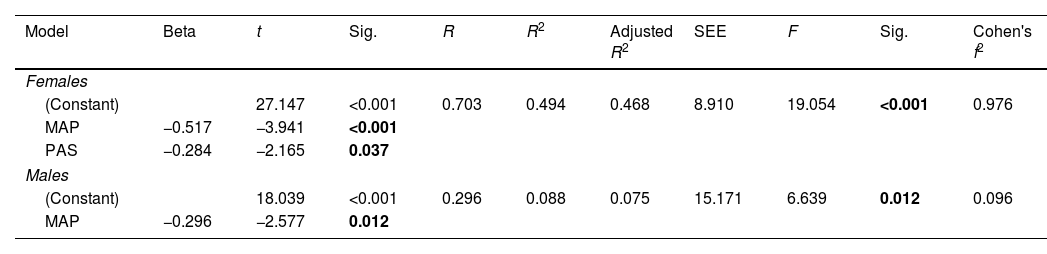

The predictors of functioning at follow-up (GAF) that differed between the sexes with interaction terms were premorbid adjustment (F=2.066, p=0.010, ηp2=0.820) and MAP (F=2.443, p=0.003, ηp2=0.303) (see Supplementary Table 3 for more details). The regression model (see Table 4) showed that lower MAP (t=−3.941, p<0.001) and better premorbid adjustment (t=−2.165, p=0.037) predicted better functioning in females at one-year follow-up (F=19.054, R2=0.494, p<0.001). Regarding males, the strongest predictor has proven to be the amotivation; higher deficits in motivation and pleasure (t=−2.577, p=0.012) predicted worse functioning (F=6.639, R2=0.088, p=0.012).

Linear regression models for predictors of functioning at one-year follow-up in females and males.

| Model | Beta | t | Sig. | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | SEE | F | Sig. | Cohen's f2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | ||||||||||

| (Constant) | 27.147 | <0.001 | 0.703 | 0.494 | 0.468 | 8.910 | 19.054 | <0.001 | 0.976 | |

| MAP | −0.517 | −3.941 | <0.001 | |||||||

| PAS | −0.284 | −2.165 | 0.037 | |||||||

| Males | ||||||||||

| (Constant) | 18.039 | <0.001 | 0.296 | 0.088 | 0.075 | 15.171 | 6.639 | 0.012 | 0.096 | |

| MAP | −0.296 | −2.577 | 0.012 | |||||||

Abbreviations: SEE=standard errors of the estimates; MAP=Amotivation and pleasure; PAS=Premorbid Adjustment Scale; MADRS=Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale. Significant differences (p<0.05) marked in bold.

Four findings emerged from the present study. Firstly, females showed lesser negative symptoms, especially those related to expressiveness rather than amotivation, a better premorbid adjustment and better psychosocial functioning than males. Secondly, there were clinically relevant improvements in negative symptoms in both groups through the first year after inclusion. Thirdly, in both male and female group, worse premorbid adjustment (PAS) and higher depressive symptoms made a significant contribution to the presence of higher deficits in expression at one-year follow-up, while positive and depressive symptoms predicted alterations in motivation and pleasure. In males, alcohol consumption also predicted deficits in motivation and pleasure at one-year follow-up. Finally, in females, lower deficits in motivation and pleasure and better premorbid adjustment predicted better functioning at one-year follow-up, while only higher deficits in motivation and pleasure predicted worse functioning in males.

Our results suggest that males showed more general negative symptoms than women measured by NSF but there was only a tendency to signification when measured by the PANSS subscale. Although PANSS is a widely used instrument for measuring symptomatology in patients with schizophrenia, it seems that Marder's factor (NSF) has several aspects of improved content validity in comparison to the original negative PANSS subscale.6,22 Factor analytic studies in PANSS found that two items (difficulty in abstract thinking (N5) and stereotyped thinking (N7)) should no longer be considered part of the negative symptom domain.32,33 In addition, females showed less expressivity impairment than males (such as flat affect), without differences in motivation and pleasure severity (i.e., anhedonia, avolition or asociality) between both groups. These results are in accordance with previous literature.34 Moreover, as expected, in the present study females showed a better premorbid adjustment and greater functionality, which is also in accordance with previous studies.12,14 Finally, although sex differences in age of onset is a replicated finding in the literature,35,36 in our study no significant differences were found in this regard. There are other studies that found no gender differences in age of onset.37 It has been hypothesized that differences in age of onset could depend on the presence or absence of family history.12,38 In addition, it should be noted that this study does not have balanced samples.

The obtained results suggest that regardless of sex, patients showed a reduction in the severity of negative symptomatology at one-year follow-up. According to our results, a meta-analysis revealed that negative symptoms decrease in almost all patients.39 Moreover, a previous study of our group found a reduction in the negative symptomatology one year after a FEP and that this change remained stable at two years.6 Thus, it seems that negative symptoms tend to be stable and persistent in the long-term, but can fluctuate in severity40 and can even improve in the early stages.

As negative symptoms are not a homogeneous construct, when comparing the predictors of MAP and EXP between males and females, we found that, regardless of sex, premorbid adjustment seems to be a good predictor of EXP, which is in accordance with previous research that has shown a strong association between premorbid adjustment and the course of negative symptoms.6,41 Moreover, in males, positive and depressive symptoms were predictors of greater amotivation.42 Regarding the predictors, in both groups premorbid adjustment and depressive symptoms at baseline made a significant contribution to the presence of higher deficits in the area of expressiveness, while positive and depressive symptoms predicted alterations in motivation and pleasure. Thus, these results could suggest that implementing early and personalized interventions at the onset of the illness, that is, after a first-episode, tailored to individual needs and paying special attention to the clinical and functional features that have been related to severe outcomes may help in their prognosis. However, further studies are required to confirm these findings. Briefly, early interventions will differ in terms of the target, independently of sex. Our results suggests that in those patients with worse premorbid adjustment and depressive symptoms, interventions should be oriented toward improving self-reflectivity, linguistic cohesion, and cognitive symptoms.43 Meanwhile, in those patients with positive and depressive symptoms, interventions oriented to increase cognitive control of positive emotions, as the Positive Emotions Programme for Schizophrenia (PEPS), could be suggested.44 The latter it is a program designed to improve pleasure and motivation in schizophrenia patients by targeting emotion regulation and cognitive skills relevant to apathy and anhedonia.44 In general, without taking sex or MAP/EXP into account, poor premorbid adjustment in the early illness stage predict negative symptom severity at follow-up.6 Thus, assessing premorbid adjustment and early interventions focused on treating negative symptoms is of paramount importance.38 Moreover, our study suggests that depressive symptoms should also be considered.

Finally, regarding psychosocial outcome prediction, in accordance with the literature, lower negative symptoms6 and premorbid adjustment predicted better functioning at one-year follow-up. It is well-known that negative symptoms account for a large part of long-term disability and poor functional outcomes. However, the study of the impact of negative symptom factors, taken as a multimodal construct, on functional outcome is of special interest. Our results showed that MAP could predict psychosocial functioning, but EXP could not, suggesting that symptoms such as anhedonia, avolition and asociality should be prioritized in assessment and focused on when developing early interventions targeting psychosocial functioning in FEP.

This study has certain limitations which must be taken into account. Firstly, no specific scale was used to assess negative symptomatology, due to constraints associated with the PANSS scale. Although it is one of the most widely used measures of negative symptom severity, we acknowledge that it has several limitations. Firstly, the PANSS scale was not designed to evaluate negative symptoms exclusively. Rather, it is a comprehensive scale for the assessment of psychopathology. Secondly, the PANSS can measure the two-correlated factor, but it was not designed for this purpose either. Thirdly, it does not evaluate the anhedonia symptom. Future studies making use of newer and improved negative symptom scales may be more appropriate for the evaluation of negative symptoms, such as anhedonia and avolition, because they capture both manifestations of the symptom, internal motivation and real world behavior. Also, due to a high percentage of patients discontinued the study before the follow-up visit (particularly due to they refused the re-evaluation), this resulted in a small sample size of women's group. Because of this, some aspects should have been considered with caution in order to extrapolate the present findings. Nevertheless, we analyzed the differences between patients who were assessed at follow-up and those who were only assessed at baseline and we found that they did not differ in terms of sex, sociodemographic, clinical and functional characteristics, except for positive symptoms measured by PSF. Finally, a limitation present in all CR studies undertaken on a psychiatric population is that as there is not yet a valid instrument to measure CR, criteria established and replicated in previous studies were followed. Finally, another potential limitation of the study is the short follow-up period and the small and unbalanced sample size. However, it is a naturalistic and multicentric study with a representative sample of FES patients in a stable clinical phase recruited from the whole Spanish territory. Furthermore, the sample is very well characterized because it includes different variables of interest.

In conclusion, clinical phenotypes in FES and its predictors can vary slightly by sex. However, our study suggests that there are no differential needs between men and women nor sex-specific personalized therapeutic strategies focused on NS. Our results lead us to consider that early interventions of negative symptoms, especially those focusing on motivation and pleasure symptoms, could improve functional outcomes. Due to the fact that the negative dimension constitutes one of the most impairing aspects of schizophrenia, and since treatments for this symptomatology have had limited success to date, it might be worthy of further investigation. A greater understanding of its impact on the functional outcome will help to change this situation, giving way to the design of longitudinal studies that focus on negative symptoms from a multidimensional approach.

Authors’ contributionsMB obtained funding for the study. GM, SA, EV, NV and MB designed the study, drafted the article, and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors have participated in the recruitment. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statementThe data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

FundingThis study received economic support from the Spanish Ministry of Economic and Competitiveness, the Carlos III Health Care Institute (Grant Numbers PI08/0208; PI11/00325; PI14/00612); the European Regional Development Fund, the European Union “Una manera de hacer Europa/A Way of Shaping Europe” and CIBERSAM; Departament de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya, en la convocatoria corresponent a l’any 2017 de concessió de subvencions del Pla Estratègic de Recerca i Innovació en Salut (PERIS) 2016–2020, modalitat Projectes de recerca orientats a l’atenció primària, amb el codi d’expedient SLT006/17/00345.

Conflicts of interestM. Bioque has been a consultant for, received grant/research support and honoraria from, and been on the speakers/advisory board of has received honoraria from talks and/or consultancy of Adamed, Angelini, Casen-Recordati, Ferrer, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Neuraxpharm, Otsuka, Pfizer and Sanofi, and grants from Spanish Ministry of Health, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI20/01066).

R. Rodriguez-Jimenez has been a consultant for, spoken in activities of, or received grants from: Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS), Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), Madrid Regional Government (S2010/BMD-2422 AGES; S2017/BMD-3740), Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Ferrer, Juste, Takeda, Exeltis, Casen-Recordati, Angelini.

A. Ibáñez has received research support from or served as speaker or advisor for Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck and Otsuka.

E. Vieta has received research support from or served as consultant, adviser or speaker for AB-Biotics, Actavis, Allergan, Angelini, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Suibb, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ferrer, Forest Research Institute, Gedeon Richter, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, Telefónica, the Brain and Behaviour Foundation, the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (CIBERSAM), the Seventh European Framework Programme (ENBREC), and the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

J.A. Ramos-Qurioga was on the speakers’ bureau and/or acted as consultant for Eli-Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, Shire, Takeda, Bial, Shionogui, Lundbeck, Almirall, Braingaze, Sincrolab, Medice and Rubió, Raffo in the last 5 years. He also received travel awards (air tickets+hotel) for taking part in psychiatric meetings from Janssen-Cilag, Rubió, Shire, Takeda, Shionogui, Bial, Medice and Eli-Lilly. The Department of Psychiatry chaired by him received unrestricted educational and research support from the following companies in the last 5 years: Eli-Lilly, Lundbeck, Janssen-Cilag, Actelion, Shire, Ferrer, Oryzon, Roche, Psious, and Rubió.

M. Bernardo has been a consultant for, received grant/research support and honoraria from, and been on the speakers/advisory board of AB-Biotics, Adamed, Angelini, Casen Recordati, Janssen-Cilag, Menarini, Rovi and Takeda.

C. De-la-Camara received financial support to attend scientific meetings from Janssen, Almirall, Lilly, Lundbeck, Rovi, Esteve, Novartis, Astrazeneca, Pfizer and Casen Recordati.

J. Saiz-Ruiz has been as speaker for and on the advisory boards of Adamed, Lundbeck, Servier, Medtronic, Casen Recordati, Neurofarmagen, Otsuka, Indivior, Lilly, Schwabe, Janssen and Pfizer, outside the submitted work.

A. Tortorella received research support and travel grants from Lundbeck and Angelini (unrelated to the present work).

G. Menculini received travel grants from Angelini and Janssen.

The rest of authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

We are extremely grateful to all participants.

This study is part of a coordinated-multicentre Project, funded by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (PI08/0208; PI11/00325; PI14/00612), Instituto de Salud Carlos III – Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional. Unión Europea. Una manera de hacer Europa, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de salud Mental, CIBERSAM, by the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya AND Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia I Coneixement (2021 SGR 01120). Departament de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya, en la convocatòria corresponent a l’any 2017 de concessió de subvencions del Pla Estratègic de Recerca i Innovació en Salut (PERIS) 2016–2020, modalitat Projectes de recerca orientats a l’atenció primària, amb el codi d’expedient SLT006/17/00345. MB is also grateful for the support of the Institut de Neurociències, Universitat de Barcelona.

S. Amoretti has been supported by Sara Borrell doctoral programme (CD20/00177) and M-AES mobility fellowship (MV22/00002), from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), and co-funded by European Social Fund “Investing in your future”.

The study has been supported by a BITRECS project conceded to N. Verdolini. BITRECS project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 754550 and from “La Caixa” Foundation.

R. Rodriguez-Jimenez thanks the support of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI19/00766; Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias/FEDER) and of Madrid Regional Government (S2017/BMD-3740).

A. Ibáñez thanks the support by the Madrid Regional Government (R&D Activities in Biomedicine and European Union Structural Funds (S2017/BMD3740: AGES-CM 2-CM) and the support by CIBERSAM.

E. Vieta thanks the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (PI18/00805; PI21/00787) integrated into the Plan Nacional de I+D+I y cofinanciado por el ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación y el Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER); CIBERSAM; and the Comissionat per a Universitats i Recerca del DIUE de la Generalitat de Catalunya to the Bipolar Disorders Group (2021 SGR 1358) and the project SLT006/17/00357, from PERIS 2016–2020 (Departament de Salut). CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya.

We also would like to thank the authors of the 2EPs group who participated in the development of this manuscript.

Maria Florencia Forte,2,3 Maria Serra-Navarro,3,4 Anna Alonso-Solís,4,11 Eva Grasa,4,11 Edurne García Corres,4,8 Jessica Fernandez Sevillano,4,8 Alba Toll,4,9 Laura Martínez-Sadurní,9 Aggie Nuñez-Doyle,4,10 Luis Sanchez-Pastor,4,10 Edith Pomarol-Clotet,4,12 Amalia Guerrero-Pedraza,4,12,18 Anna Butjosa, 4,14,19, Marta Pardo,4,14,19 Jose M. López-Ilundain,5,6 María Ribeiro,5,6 Jerónimo Saiz-Ruiz,13 Leticia León-Quismondo,13 María José Escarti,20 Fernando Contreras,4,21 Concepción De-la-Cámara,4,22 Arantzazu Zabala Rabadán,4,23 M Paz Portilla24

18 Hospital Benito Menni, Sant Boi de Llobregat, Spain.

19 Hospital Infanto-juvenil Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona, Spain.

20 Department of Psychiatry, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, Spain; Biomedical Research Institute INCLIVA, Fundación Investigación Hospital Clínico de Valencia, Valencia, Spain.

21 Psychiatry Deparment. Bellvitge Universitary Hospital. IDIBELL, Barcelona, Spain.

22 Hospital Clínico Universitario and Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria (IIS) Aragón, Zaragoza, Department of Medicine and Psychiatry. Universidad de Zaragoza, Spain.

23 University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) Vizcaya, Spain. BioCruces Health Research Institute, Spain.

24 Psychiatry Department, Medical Center of Asturias, Oviedo, Spain.