Suicide is one of the most largely preventable causes of death worldwide. The aim of the STRONG study is to assess the effectiveness of a specific intervention (an extended Safety Planning Intervention) called iFightDepression-SURVIVE (iFD-S) in suicidal attempters by changes in psychosocial functioning. As secondary outcomes, quality of life, cognitive performance, clinical state and neuroimaging correlates will be considered.

ObjectiveTo describe the rationale and design of the STRONG study, an extension of the SURVIVE study, a national multicenter cohort about on prevention in suicidal attempters.

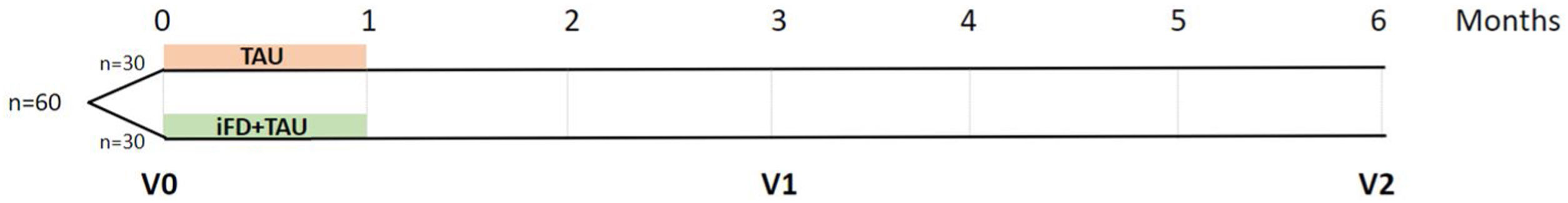

MethodsThe STRONG study is a two-year clinical trial. A total sample of 60 patients will be randomly allocated to two arms: a group will receive a iFD-S and treatment as usual (TAU) (n=30 treatment group), while another group will exclusively receive TAU (n=30 control group). There will be three study points: baseline; 3-month; and 6-month follow-up assessments, all of which will include rater-blinded evaluation of psychosocial functioning, quality of life, clinical state, cognitive performance and neuroimaging acquisition.

ResultsIt is expected to obtain data on the efficacy of iFD-S in patients who have committed a suicide attempt.

ConclusionResults will provide insight into the effectiveness of IFD-S in suicidal attempters with respect to improvements in psychosocial functioning, quality of life, cognition, and neuroimaging correlates.

Clinical trials IDNCT05655390.

Suicide is a global public health issue. It is one of the most largely preventable causes of death worldwide and concerns all health professionals. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 703,000 suicides are committed per year, while approximately 20 more people attempt suicide per consummated suicide.1 This complex phenomenon is transdiagnostic, and to prevent suicide it is crucial to understand the natural course of suicidal ideation and behavior, as well as the dynamical influence of both protective and risk factors. Improving our knowledge of these factors is essential for developing effective interventions to prevent the transition from suicidal ideation to attempted and completed suicide. The prevalence and characteristics of subjects with suicidal ideation, suicidal attempts and death by suicide essentially differ.2–4 Having committed a suicidal attempt is the strongest predictor of suicide consummation.

Factors that trigger a suicide attempt may be attributable to genetic and neurobiological correlates,5–7 mental illness,8 personality traits,9 stressful events10 and cognitive deficits.11 According to neurobiological factors, it is always difficult to discern the extent to which these alterations are particular of suicidal behavior or are commonly shared with depression or any other mental disorder. Regarding the latter, mental health disorders are tightly related to suicide. The prevalence of any mental disorder among individuals who have made a suicide attempt is currently established as being 80.8%.8 On comparing general population with people diagnosed with mood disorders, the latter present a 7-fold higher risk of attempting suicide. Personality, anxiety and impulsive-aggressive traits have been the most robustly associated with higher rates of suicide attempts within the context of borderline personality disorder, oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorders. Stressful events, especially in particular early-life events, are strongly associated with suicidal behavior through expression of epigenetic mechanisms.

Neurocognitive deficits, especially those in executive functions, have also been linked to the transition from suicidal ideation to suicide attempt. Previous research has consistently placed decision-making, inhibition, and attention as the primary axis of neurocognitive deficits in suicide attempters.12 Specifically, alterations in decision-making have commonly been described and often more pronounced in this population at risk. Suicidal individuals may reflect difficulties in labeling emotional signs, such as differentiating risky versus safe choices. Therefore, suicidal individuals may be prone to more risky choices, such as attempting suicide, which may alleviate punctual emotional suffering, but may have a more severe impact in the long term.11 In addition, several studies have shown that decision-making is impaired in subjects with a history of suicide attempts but not with suicidal ideation in adults.13,14 Deficits in attention have also been described in patients who have attempted suicide. Deficits in selective attention may therefore make suicidal individuals more prone to persistent thoughts related to a sense of hopelessness.15 Altogether, these cognitive deficits may impair psychosocial functioning of suicide attempters as well as their quality of life.

Studies on neuroimaging have been performed to identify the neural correlation of decision-making. Jollant et al. performed functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) in patients who had attempted suicide compared to patients without a history of attempted suicide and detected that orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) activation was decreased during risky choices compared to safe choices.16 Olié et al. described a deactivation in the dorsal prefrontal cortex (DPFC) during risky compared to safe choices.17 These results are in line with the assumption that the role of the OFC is to assess the level of risk according to a reward value, while the DPFC is involved in the cognitive control of actions.18 Cognitive control is highly associated with cognitive inhibition and ultimately to cognitive flexibility and a reduction in impulsivity as it enables one's behavior to adapt to external demands that may be challenging and unpredictable. Richard-Devantoy et al. described an elevated number of commission errors in suicide attempters with depression in comparison to depressed patients and healthy controls.19 In summary, to date, the most robust findings have described the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC), the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and the anterior cingulate gyrus as the main and most replicated areas, associated with suicidal behavior.

During the last few years, specific psychosocial interventions have been focused on the treatment of suicidal urge in addition to the treatment of possible underlying psychiatric comorbidities. Although long-term psychosocial interventions, irrespective of type, have been shown to reduce suicide attempts,20 the limited resources of the National Health System, as well as the reluctance of most people who become suicidal to receive treatment have promoted brief psychosocial interventions.21 Brief interventions are easier to implement, inexpensive and require limited staff resources since they are delivered in a few sessions. Moreover, this format does not always require face-to-face interventions. Commonly, this type of intervention is offered to patients who have attended an emergency department for a suicidal attempt. One of the brief psychosocial interventions that has demonstrated a reduction in the risk of suicide attempts is the Safety Planning Intervention (SPI).22 The iFightDepression-SURVIVE (iFD-S) consists of a SPI and three modules based on dialectical-behavioral skills training: distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and mindfulness has been assessed to determine the effectivity of reducing reattempts among suicidal.4 The aim of this specific therapy is to help individuals to acquire strategies to regulate emotions and learn to tolerate discomfort and thereby prevent the imminent risk of suicidal behavior. However, the possible effects of iFD-S on psychosocial functional, cognitive performance and quality of life and its possible neuroimaging correlates in suicide attempters have barely been studied. To our knowledge, there is only one previous preliminary study describing an improvement in executive attention in high-suicide risk outpatients regardless of changes in suicidal ideation or depression.23

ObjectiveThe main objective of this project is to assess the effectiveness of iFD-S intervention in suicide attempters by improving psychosocial functioning and thereby enhancing their ability to perform daily life activities. Moreover, we aim to describe whether the implementation of this intervention improves cognitive performance (particularly in decision-making, inhibition and attention), clinically and the quality of life of suicide attempters. Finally, we will also estimate possible neuroimaging correlations on the prefrontal cortex, specifically in the vlPFC, dmPFC, dlPFC and the anterior cingulate gyrus.

MethodsDesignSTRONG is a randomized, single-center, experimental clinical trial including suicide attempters undergoing an iFD-S intervention and 3- and 6-month follow-ups. This study will be carried out in the Bipolar and Depressive Disorders Unit of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. It will be rater-blinded and will include two parallel arms (1:1) to assess the efficacy of iFD-S compared with treatment as usual (Fig. 1).

Sample size calculationTo achieve a statistical power of 0.80, an alpha error of 0.05 and an effect size of 0.6 on the main outcome assessed by the Functional Assessment Short Test (FAST) a sample size of 45 was estimated. Considering an expected drop-out rate set of around 15%, 15 patients per arm were added. Therefore, the sample of the total suicide attempters was determined to be n=120.

ParticipantsThe study will include 60 suicide attempters recruited from the Psychiatric Emergency Department, the Adult Mental Health Outpatients Unit of the Eixample Esquerre (CSMA-EE), the Day Care Hospitalization Unit, the Day Home Hospitalization Unit and the Liaison Psychiatric Program. The whole sample will be randomized into two groups: the experimental arm (n=30) will receive iFD-S and treatment as usual (TAU); and the control arm, or non-interventional group will receive TAU (n=30). All participants must meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) age over 18 years; (2) at least one suicide attempt within 10 days after medical discharge; (3) diagnosis of a recent Major Depressive Episode (DSM-5-TR criteria) with a severity of HDRS >20; (4) able to provide written informed consent before any study procedure; and (5) no claustrophobia or any other hindrances to perform a fMRI. The exclusion criteria will be: (1) intelligence quotient less than 70 and impaired functioning; (2) any medical condition that could severely affect neuropsychological performance; (3) participation in any structured psychological intervention within the last six months; (4) patients who received electroconvulsive therapy within the past six months. Criteria for study discontinuation will be: (1) withdrawal of consent, (2) not completing half of the sessions, or (3) hospitalization for any type of episode or clinically meaningful relapse. Moreover, same number of patients with only a diagnosis of a recent Major Depressive Episode (DSM-5-TR criteria) with a severity of HDRS >20 (n=30) and healthy controls (n=30) will be recruited.

ProceduresAfter signing the informed consent, a complete baseline evaluation will be carried out including the acquisition of socio-demographic and clinical variables, psychosocial functioning, cognitive performance, quality of life assessment and neuroimaging determinations (V0). Thereafter, the whole sample will be randomized into two groups of 30 participants by parallel assignment. A group of 30 participants will receive iFD-S in addition to TAU (experimental group) and a group of 30 people will exclusively receive TAU (non-intervention group). Two months after finishing the 4-week intervention (or three months after baseline), suicide attempters will be reassessed by socio-demographic, clinical, psychosocial functioning, quality of life assessment as well as a brief neuropsychological evaluation (V1). The neuropsychological assessment performed at this point will be shorter to avoid learning effects. Five months after the intervention (or six months after baseline), a complete socio-demographic, clinical psychosocial functioning, quality of life assessment as well as neuropsychological and neuroimaging evaluation will be carried out (V2).

InterventionThe Psychological intervention will be conducted with the aim of identifying warning signs and providing each individual with personal and individualized coping strategies and sources of support. This intervention will be conducted weekly and individually based on an on-line platform derived from the iFightDepression-SURVIVE (iFD-S) with the support of a mental health provider. Full psychological intervention will include four sessions (over one month). Each session will last approximately 60min. The mental health provider in charge will contact the patient by phone for 15–20min after each weekly session. Most of the tasks in this population group will use pen-and-paper techniques with audiovisual support. Detailed information about the iFD-S can be found in Supplementary Materials.

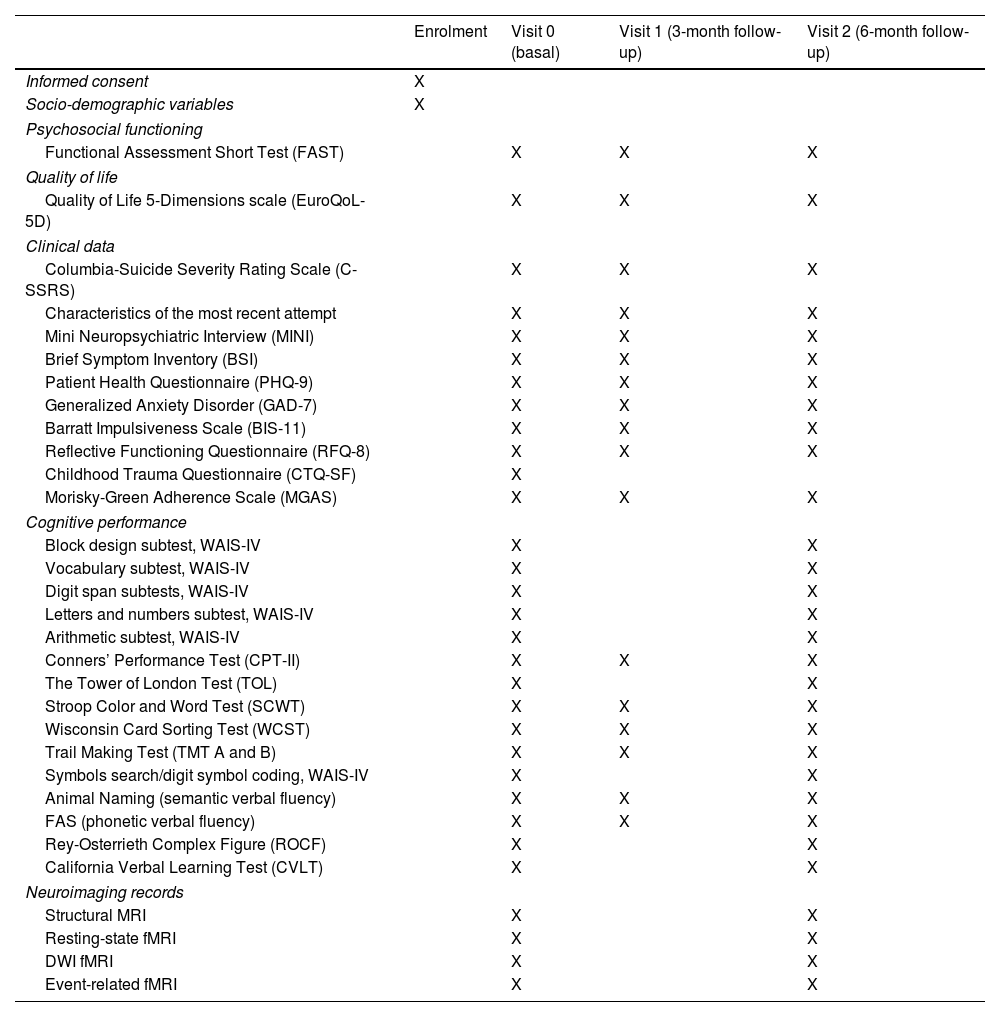

Data collectionA spirit diagram is included with all the information about the time and events to be carried out in our study (see Table 1 for more information). The type of variables to be collected and their nature can be found below together with instruments to be used.

- (a)

Socio-demographic variables: At baseline, the following information will be collected ad hoc by self-reporting at baseline in a clinical interview (V0): native language, age, gender, marital status, current type of cohabitation, number of offspring (if any), educational level, years of education, employment status, socioeconomic status, country of origin and religious preferences. Any changes in marital, employment status or similar that have taken place during the study period will be recorded at the last visit (V2).

- (b)

Clinical, psychosocial functioning, quality of life evaluation: Suicidal ideation and behavior, as well as characteristics of the most recent attempt (in terms of method, use of substances before/during the attempt, and family history of suicide), psychiatric diagnosis (if any), family history of affective and psychiatric disorders, and pharmacological treatment will be assessed in a clinically monitored interview. Other clinical symptomatology will be collected by self-reporting at baseline, including recent depressive and anxious symptoms, clinical symptomatology and possible psychopathology, impulsiveness, reflective functioning and childhood trauma. Except for childhood trauma, all clinical variables will again be assessed at three and six months after the baseline visit (V0). Clinical measures will be assessed by different scales and questionnaires that are available for consultation in Supplementary Materials.

- (c)

Neuropsychological assessment: All subjects will be assessed using the extended neuropsychological battery (at baseline and at the 6-month follow-up), and with the abbreviated version (3-month follow-up). Only attentional and executive function measures will be collected with the latter battery, which was specifically designed to avoid learning effects by only covering an exploration of the main outcomes expected for the purpose of our study. The extended neuropsychological battery will include: intelligence quotient, processing speed, attention, working memory, verbal and visual memory, and executive functions. A structured explanation including all the variables and tests can be found in Supplementary Materials. Only the Conners’ Performance Test (CPT-II), the Stroop Color and Word Test (SCWT), and the Trail Making Test (TMT) and verbal fluencies are included in the abbreviated neuropsychological battery.

- (d)

Neuroimaging records: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) will be performed at baseline, and at 6-month follow-up. Data acquisition will be performed using a full-body MRI scanner (Siemens MAGNETOM Prisma 3T) at the Magnetic Resonance Imaging Core Facility at IDIBAPS. The neuroimage protocol to be used in the present study includes a structural T1-weighted image, resting-state fMRI, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and task-based fMRI related to decision-making (Iowa gambling task).24 Neuroimaging protocol including all parameters and regions of interest are available for consultation in Supplementary Materials.

Spirit diagram: time and events table STRONG study including all measuring variables.

| Enrolment | Visit 0 (basal) | Visit 1 (3-month follow-up) | Visit 2 (6-month follow-up) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informed consent | X | |||

| Socio-demographic variables | X | |||

| Psychosocial functioning | ||||

| Functional Assessment Short Test (FAST) | X | X | X | |

| Quality of life | ||||

| Quality of Life 5-Dimensions scale (EuroQoL-5D) | X | X | X | |

| Clinical data | ||||

| Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) | X | X | X | |

| Characteristics of the most recent attempt | X | X | X | |

| Mini Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) | X | X | X | |

| Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) | X | X | X | |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) | X | X | X | |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) | X | X | X | |

| Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) | X | X | X | |

| Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (RFQ-8) | X | X | X | |

| Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-SF) | X | |||

| Morisky-Green Adherence Scale (MGAS) | X | X | X | |

| Cognitive performance | ||||

| Block design subtest, WAIS-IV | X | X | ||

| Vocabulary subtest, WAIS-IV | X | X | ||

| Digit span subtests, WAIS-IV | X | X | ||

| Letters and numbers subtest, WAIS-IV | X | X | ||

| Arithmetic subtest, WAIS-IV | X | X | ||

| Conners’ Performance Test (CPT-II) | X | X | X | |

| The Tower of London Test (TOL) | X | X | ||

| Stroop Color and Word Test (SCWT) | X | X | X | |

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) | X | X | X | |

| Trail Making Test (TMT A and B) | X | X | X | |

| Symbols search/digit symbol coding, WAIS-IV | X | X | ||

| Animal Naming (semantic verbal fluency) | X | X | X | |

| FAS (phonetic verbal fluency) | X | X | X | |

| Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure (ROCF) | X | X | ||

| California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) | X | X | ||

| Neuroimaging records | ||||

| Structural MRI | X | X | ||

| Resting-state fMRI | X | X | ||

| DWI fMRI | X | X | ||

| Event-related fMRI | X | X | ||

WAIS-IV: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; WMS-III: Wechsler Memory Scale III; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imagining; FMRI: functional MRI; DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging.

The primary outcome will be changes observed after the intervention assessed by FAST in all six domains for exploring psychosocial functioning. Other secondary outcomes will be: (i) changes in cognitive performance in the experimental group versus the control group particularly in decision-making measures, as well as in inhibition and attention related tasks; (ii) improvement in quality of life in the experimental group; and (iii) greater clinical improvement in the experimental group. All these changes are expected to last at least for five months after receiving treatment. Moreover, possible modifications in the activation, morphology, and connectivity of the orbitofrontal and prefrontal cortices will be shown in those suicidal attempters receiving psychological intervention.

Statistical analysisFirstly, to test the normality of the sample distribution and the equality of variances, Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Levene's tests will be performed. Secondly, a descriptive analysis of the sample will be carried out to explore possible baseline differences between the two groups (experimental and control). Means, standard deviations and ranges will be used to describe continuous variables and frequencies and percentages will be calculated to describe the categorical variables. Psychosocial functionality (main expected outcome) as well as quality of life, neuropsychological performance and clinical state will be explored in terms of changes in stability analyzing significant differences considering 3-time-points (V0, V1 and V2). Multilevel mixed-effect logistic regression models (categorical variables) or multilevel mixed-effect linear regression models (continuous variables) will be used. Group, time, and group×time interaction will be included in the model as fixed factors. If significant differences are detected between groups, socio-demographic, and clinical variables will also be included as fixed factors. To explore possible differences in neuroimaging records between 2-time-points (V0 and V2) with six months difference (pre- and post-intervention), chi-square or Student's t-tests or ANCOVA analysis will be applied to compare categorical and continuous variables when appropriate. For neuroimaging data, we will also conduct exploratory whole-brain analyses.

In all cases, the level of significance will be set at p<0.05. When needed, all analyses will be corrected by the Bonferroni model for multiple comparisons. The data will be analyzed using the IBM SPSS statistical package (version 23).

EthicsThe study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clinic with the registration number: HCB2022_0659. The study design and the evaluation of the results will be carried out following the CONSORT criteria. All data will be collected following the current Law of Data Protection. All participants must give written informed consent prior to inclusion. All the data collected will be confidential. All Case Report Forms will be anonymized with a code for each subject. Neither the name nor any personal data that could identify an individual will be registered in the database. Only personnel involved in the present project will have access to the data collected. The Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona will be made aware of any important changes in the protocol by a written report. This protocol was registered in Clinicaltrials.gov with ID number: NCT05655390. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice.

ResultsSTRONG study was conceived to implement specific secondary prevention strategies addressed to improve functional performance on patients who have committed a suicide attempt. STRONG study is an extension of the SURVIVE project.

SURVIVE project is a Spanish multicenter cohort study with three nested randomized controlled clinical trials (for more information about the SURVIVE study see4). In the SURVIVE study a total of 1746 individuals older than 12 years old who had attempted suicide have been recruited from different University hospitals up to 31st March 2023. Currently the follow-ups of these patients are being completed. The preliminary results of the SURVIVE study included in the Supplementary Material aim to display the feasibility of the current clinical trial.

ConclusionSuicide is still one of the most frequent causes of death worldwide despite the huge effort of the health organizations to reduce death by this non-accidental cause. In this context, the proposal of this project is aligned with different lines of the Spanish Strategy of Science, Technology and Innovation 2021–2027. Moreover, this project is also in line with the priority topic of the National Strategic Health Action (AES) 2021–2023 within the frame of Horizon Europe.

The present study is among the first studies to combine the search for findings in neuroimaging and cognition when proposing a psychological intervention for suicide attempters. Previous studies have shown that psychotherapies such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)-based interventions can reduce suicide attempts.25 For the present study, our main interventional tool is based on one of these CBTs. Moreover, the fact that it is self-administered and can be used remotely is helpful to increase patients’ engagement and provide facilities to complete all the training without the need to travel to our center for each of the stipulated interventions, or to be overstimulated and so overwhelmed by too much information at once because of previously planned sessions by a therapist. This is an extension of the SURVIVE study that adds more parameters to be measured pre- and post-intervention.

All in all, incorporating longitudinal methods into suicide intervention research is essential when working on suicidal behavior to not only prevent but also investigate and propose possible future treatments to diminish the number of suicide attempts or deaths and collateral damages resulting from these behaviors.

Authors’ contributionsNR and IG conceived the study with substantial contributions from EV. Clinical and research recommendations were given by AMA and JSM. Neuroimaging acquisition and post-processing for the purpose of the study will take place at the Magnetic Resonance Imaging Core Facility and will be supervised by the Imaging of Mood, Anxiety and Related Disorders link group (JR, JCP, EMM, CL and their unit). PB and PC collaborated by designing and adapting the neuroimaging protocol to address the needs and objectives of the study. LB, TF and MV were actively involved in patient recruitment. AT, ME and VPS provided information on the SPI protocol and guidelines on the implementation of the psychological intervention. NR and IG wrote the first draft with contributions from the whole team. All authors participated in and approved the final draft for submission to the journal. All have read and approved the manuscript. The Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS) will be responsible for the recruitment, as well as for the assessment of patients at baseline and at subsequent follow-ups. The whole group will oversee publications. Results from this study will be disseminated through international scientific meeting and will also be published in international indexed journals.

FundingAuthors would like to thank the Hospital Clínic Provincial de Barcelona (Pons-Bartran PB1-2022-FRCB_PB1_2022) and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MCIN) (PI19/00954) for their support.

Conflict of interestsMV has served as consultant for Lundbeck and Otsuka.

AMA has received funding for research projects and/or honoraria as a consultant or speaker for the following companies and institutions: Otsuka, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Siquibb, Lundbeck, Brain and Behaviour Foundation (NARSAD Independent Investigator), the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

Víctor Pérez has been a consultant to or has received honoraria or grants from AB-Biotics, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, CIBERSAM, FIS-ISCIII, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Servier, and Pfizer. MJP has received honoraria from CIBERSAM, FIS-ISCIII, Lundbeck and Janssen.

IG has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following identities: ADAMED, Angelini, Casen Recordati, Ferrer, Janssen Cilag, and Lundbeck, Lundbeck-Otsuka, Luye, SEI Healthcare outside the submitted work. The rest of authors declare no conflict of interests related.

EV has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities: AB-Biotics, AbbVie, Adamed, Angelini, Biogen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celon Pharma, Compass, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ethypharm, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, GH Research, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Janssen, Lundbeck, Medincell, Merck, Novartis, Orion Corporation, Organon, Otsuka, Roche, Rovi, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, Takeda, and Viatris, outside the submitted work.

PAS has been a consultant to and/or has received honoraria/grants from Adamed, Alter Medica, Angelini Pharma, CIBERSAM, Ethypharm Digital Therapy, European Commission, Government of the Principality of Asturias, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Plan Nacional Sobre Drogas, and Servier.

NR, MV, JR, JCP, EMM, CL, LB, TF, SMP, JSM, PS, MRV, RB, ME, PB, PB and PC declare no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

JR thanks the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PI19/00394, CPII19/00009) integrated into the Plan Nacional de I+D+I and co-financed by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII)-Subdirección General de Evaluación and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER); the ISCIII; the CIBER of Mental Health (CIBERSAM); the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement (2021 SGR 01128), the CERCA Program.

IG gives thanks for the support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MCIN) (PI19/00954) integrated into the Plan Nacional de I+D+I and co-financed by the ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación y confinanciado por la Unión Europea (FEDER, FSE, Next Generation EU/Plan de Recuperación Transformación y Resiliencia_PRTR); the Instituto de Salud Carlos III; the CIBER of Mental Health (CIBERSAM); and the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement (2021 SGR 01358), CERCA Program/Generalitat de Catalunya as well as the Fundació Clínic per la Recerca Biomèdica (Pons-Bartran 2022-FRCB_PB1_2022).

EV wishes to acknowledge the support from CIBER – Consorcio Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red – (CB07/09/0004), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PI18/00805, PI21/00787), Instituto de Salud Carlos III – Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER). Unión Europea. “Una manera de hacer Europa”, cofinanciado por la Unión Europea; the CERCA Program/Generalitat de Catalunya and Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia I Coneixement (2021 SGR 01358). Departament de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya, Pla Estratègic de Recerca i Innovació en Salut (PERIS) 2016-2020 (SLT006/17/00357). Thanks are also given for the support received from the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (EU.3.1.1. Understanding health, wellbeing and disease: grant no. 754907 and EU.3.1.3. Treating and managing disease: grant no. 945151).

ME has a Juan de la Cierva research contract awarded by the ISCIII (FJCI-2017-31738). VP, ME, and AT want to thank unrestricted research funding from “Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement” (2017 SGR 134 to “Mental Health Research Group”), Generalitat de Catalunya (Government of Catalonia).

PAS has received partial support from the Government of the Principality of Asturias PCTI-2021-2023 IDI/2021/111, the Fundación para la Investigación e Innovación Biosanitaria del Principado de Asturias (FINBA), and Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, and Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación. The funders had no role in the study design, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

We are indebted to the Magnetic Resonance Imaging Core Facility of the Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS) for the scientific and technical support in MRI acquisition and analysis. This work has been performed thanks to the 3T MRI equipment at IDIBAPS (grant IBPS15-EE-3688 co-funded by MINECO and by ERDF).