In the last twenty years the relationship between Management Control Systems (MCS) and strategy has become a relevant issue to management control investigation. This study aims to understand how managers use the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) to support the processes of implementation and formulation of strategy. The research adopts an exploratory case study approach and was conducted on a business unit of a large industrial Portuguese company. Results were analyzed from the standpoint of Simons’ four control levers (1995, 2000), and demonstrate that the BSC methodology may be used under a diagnosis mode to implement deliberated strategies and, simultaneously, under an interactive mode to promote learning, support strategy revision, and provide conditions for new strategies. The research provides insights into the relationship between MCS and strategy, as it identifies the characteristics of using the BSC in the several levers of control.

Discussion about the relation between Management Control Systems (MCS) and strategy is fairly new. The variable strategy is only openly used in Management Control (MC) investigation papers in the last three decades (Langfield-Smith, 1997). Until then, MC was viewed as a set of mechanisms created for the purpose of producing information to support planning and control, favoring financial control and accounting related information. During the decade of 80, investigation starts to relate MC and strategy based on the contingency theory. However, these studies have been widely criticized on because they do not facilitate the interpretation of results within an integrated model, the identified relationships are weak and the results are fragmented (Chenhall, 2003; Chenhall & Chapman, 2006; Covaleski, Dirsmith, & Samuel, 1996; Dent, 1990; Hopper, Otley, & Scapens, 2001; Langfield-Smith, 1997; Otley, 1999; Wickramasinghe & Alawattage, 2007). Starting in the mid-decade of 90, research highlighted the active role assumed by MC on the process of strategy formulation and strategy change. Conducted research assumes that strategy influences MCS and these can influence strategy. The studies of Simons (1987, Simons, 1987, 1990, 1991, 1994, 1995, 2000) have provided important contribution for this new vision of MC. The conceptual framework of Simons highlights the way managers can use MCS to define and implement strategy and also promote strategic change (Langfield-Smith, 1997).

Along with the interest on the way that MCS influence strategy, the decade of 90 also witnessed the emergence of the concept of performance management, as well as its relationship with strategy (Ittner & Larcker, 2001). The era of performance management introduces, in academic research and corporate practice, a set of management techniques focused on value creation, where the BSC is included. Some studies on the use of performance measurement systems suggest that these type of techniques are used to support strategy implementation (Bhimani & Langfield-Smith, 2007; Chenhall, 2005; Dixon, Nannim, & Vollmann, 1992; Henri, 2006; Ittner & Larcker, 2005; Marginson, 2002; Mooraj, Oyon, & Hostettler, 1999; Tuomela, 2005), as well as to promote strategic changes (Henri, 2006; Ittner & Larcker, 2005; Jazayeri & Scapens, 2008; Kaplan & Norton, 2001; Mooraj et al., 1999; Otley, 1999; Simons, 1995; Tuomela, 2005; Vaivio, 1999, 2004).

Therefore, the research questions considered in this investigation are: how do managers within the Business Unit (BU) use the BSC, and how is the BSC implicated in the process of strategy implementation and strategic change? Our research focuses on the use of the BSC, on its diagnosis and interactive mode, and its relationship with strategy implementation and change, rather than on the BSCs technical details. A qualitative methodology and a case study method were adopted to better understand the processes and context in which the practices of management control take place.

This paper provides some contributions. This research explains, with detail, how managers, from a practical standpoint, use the BSC to implement strategy and promote new strategic initiatives, generating practical contributions to corporations. Second, this research contributes to the theorization on the methodology of the BSC, which is not abundant, leading several researchers to criticize this performance measurement system (Marr & Schiuma, 2003; Norreklit, 2000, 2003). The research on the BSC is considered insufficient and some of the premises do not foster consensus across the research community. This paper aims to secure further knowledge on the form that managers use the BSC and leverage other management processes with it.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 presents the literature review and propositions which are used to guide fieldwork and subsequent analysis. Section 3 draws the research methodology and design. Results from this investigation are described in Section 4 and Section 5 contains conclusions. Finally, in Section 6 limitations and issues for future research are displayed.

2Theoretical underpinningsSimons (1995, 2000) presented a framework that relates four types of control with implemented strategies and with emerging strategies:

- •

The diagnosis management systems result in the management tools that are capable of transforming planned strategies into implemented strategies;

- •

The interactive control systems motivate managers to seek opportunities that might result in strategic changes and, later, in implemented strategies;

- •

The belief systems inspire employees to implement planned strategies but also to look for opportunities for change, as long as they are aligned with the organizational mission;

- •

The frontier systems assure that implemented actions are coherent with defined product and market strategies.

Control and business strategies implementation imply the integration and balance of the four control levers. And the effectiveness level which is achieved in the implementation of the planned strategies and in the identification, formulation, and implementation of emerging strategies depends on the way that the four control levers are used by managers and how they complement each other. The belief and interactive control systems foster creativity and the search for new opportunities, creating an organizational environment that stimulates information sharing and the organizational learning process. The frontier system and the use of control systems for diagnosis are used to guide behaviors, imposing managers some action frontiers and focusing them on the defined objective set and reward criteria.

Literature review focused on the framework of Simons (1995, 2000) and on the studies that used the four control levers to study the relationship between management control tools and strategy.

The studies of Simons determined the course of research on the relationship between the MCS and strategy. Part of the most recent research on this theme, has proved the work hypothesis in the model of Simons (1995, 2000), especially in the use of management control in the diagnosis or interactive mode, and in the impact of different management control modes in the implementation and strategic changes (Abernethy & Brownell, 1999; Bisbe & Malagueno, 2015; Bisbe & Otley, 2004; Kober, Ng, & Paul, 2007; Marginson, 2002). Nevertheless, the results are not consensual.

Abernethy and Brownell (1999) analyzed the way the budget was used within a context of strategic change and collected evidence that the use of the budget in interactive mode responds better to the learning and adaptation needs in a context of strategic change.

Marginson (2002) sought, through a case study, to understand the relationship between management control and strategy, exploring how (and why) the model and the use of MCS may affect the autonomy of managers in the development of new ideas and initiatives. Based on the model of Simons (1995, 2000), he concluded that: the system of beliefs and values may be used as a strategic change mechanism; the tools of administrative control may be used at the various levels of the organization to assure the strategy implementation; and, the key performance indicators may be used to secure performance in the critical strategic areas. The obtained results validate the conceptual framework of Simons (1995, 2000).

The results of the study of Bisbe and Otley (2004) show that there is no positive relation between the use of management control in the interactive mode and product innovation, countering the assumptions of Simons (2000). Research suggests that the interactive management control seem only to hold any positive influence in companies with reduced innovation levels; in highly innovative companies, the interactive use of management control reduces the initiatives of product innovation.

The work developed by Kober et al. (2007) studies the interaction between management control and strategy. Moving away from the classical view that management control adapts to the strategy of the organization, Kober et al. (2007) resorted to the model of Simons (1995, 2000) and tested, on one hand, if the use of interactive management control facilitates strategic change and, on the other, if the mechanisms of management control altered as a result of a strategic change. They concluded that management control systems influence and are influenced by strategy: the mechanisms of management control used by interactive mode facilitate strategic change and, on its turn, the management control mechanisms adapt to the strategic changes that take place.

Bisbe and Malagueno (2009), analyzing a sample of medium-sized Spanish companies, conclude that the specific choice of an individual MCS for interactive use is related to the type of innovation mode that the company is dedicated to. In this sense, the authors found evidence that companies dedicated to simple and isolated forms of innovation and companies looking to create a rich portfolio of innovation usually tend to select PMS for interactive use. Bisbe and Malagueno (2015) studied how management accounting and control systems influence product innovation, and concluded that interactive control systems have a significant effect on the creativity, coordination and knowledge integration.

Chenhall, Kallunki, and Silvola (2011) contribute to the debate in the literature by examining, through a survey research in Russian companies, how the MCS are involved in the relationship between strategies of product differentiation and innovation. By doing it, the authors can find evidence that formal controls have some influence in helping companies developing innovations. Chenhall and Moers (2015) report that to be effective in management of both innovation and efficiency, the levers of control framework must have the four levers working together. The authors stated that BSC has had a significant impact in the way we think about relating MCS and strategy innovation.

Other researchers have studied the way that performance evaluation systems are used by managers (Henri, 2006; Jazayeri & Scapens, 2008; Ramos & Hidalgo, 2003; Tuomela, 2005; Widener, 2007) and what benefits have resulted of the interactive use of performance measures (Tuomela, 2005).

Ramos and Hidalgo (2003) concluded that the use of performance measurement systems might evolve from the diagnosis mode to the interactive mode.

Tuomela (2005) developed a long longitudinal case study and the results show that the performance measurement system (in the specific case the scorecard) may be used as diagnostic on interactive control systems. The use of performance measurement systems through interactive mode presents benefits when compared with the use through the diagnosis mode.

Henri (2006) found support on the resource-based theory and studied the relationship between the use of performance measurement systems and organizational capabilities inductive of strategic choices. Results are consistent with the model of Simons (2000): the management control tools not only contribute for the implementation of planned strategies but also stimulate the emergence of new strategies.

The study of Widener (2007) shows that strategic risk and strategic uncertainties determine the importance and the way management control is used. It still suggests that belief systems and the use of management control tools for diagnosis facilitate the efficient use of managers’ attention, while the interactive mode consumes managers’ attention. The belief systems and the use of management control for diagnosis promote organizational learning.

Jazayeri and Scapens (2008) have concluded that, in this case, the performance measurement system was used to allow that strategies emerged within the organization and not as an implementation tool of planned and top-down decentralized strategies.

Several researchers have focused on the way that performance measurement systems (like the BSC) and the performance measures are used in organizations. Opinions are consensual – the BSC and the performance measures are privileged mechanisms of management control used in the interactive mode (Ittner & Larcker, 2005; Kaplan & Norton, 2001; Mooraj et al., 1999; Otley, 1999; Simons, 2000; Vaivio, 1999, 2004).

In sum, a significant set of published research, since the decade of 90, focuses on the relation of performance measurement systems, highlighting non-financial metrics, and the process of strategy implementation and change. Some researchers studied if the performance measurement systems, like for example the BSC, can be used of an interactive form. Major conclusions suggest that: (1) performance measurement systems can be used as diagnosis instruments to support strategy implementation (Bhimani & Langfield-Smith, 2007; Chenhall, 2005; Dixon, Nanni, & Vollmann, 1992; Henri, 2006; Ittner & Larcker, 2005; Marginson, 2002; Mooraj et al., 1999; Tuomela, 2005); (2) performance measurement systems can be used interactively and, therefore, can lead to the emergence of strategic changes (Henri, 2006; Ittner & Larcker, 2005; Jazayeri & Scapens, 2008; Kaplan & Norton, 2001; Mooraj et al., 1999; Otley, 1999; Simons, 1995; Tuomela, 2005; Vaivio, 1999, 2004).

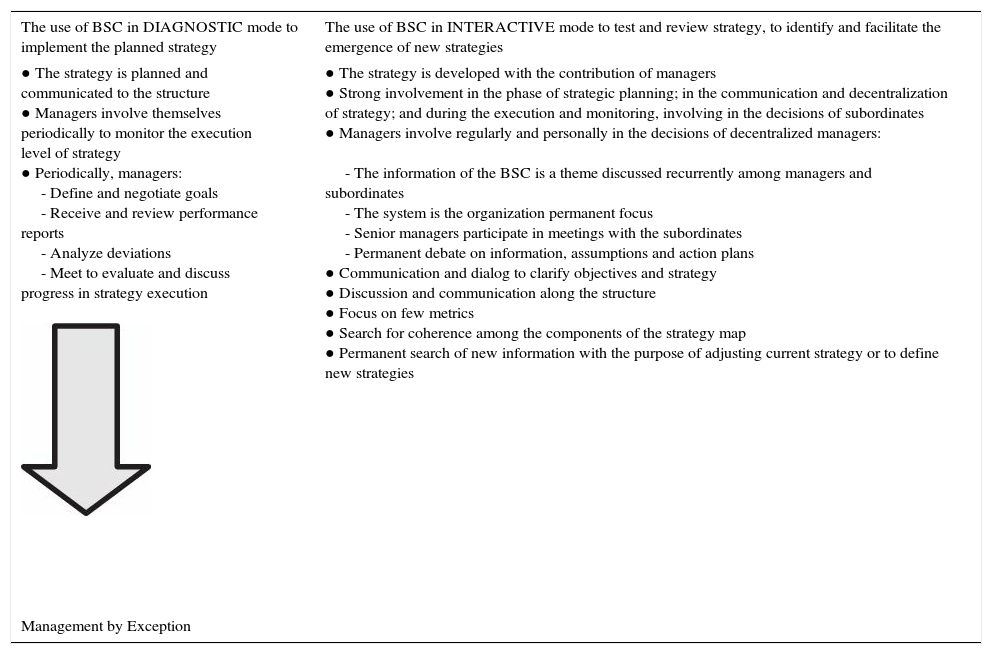

This paper investigates how managers use the BSC to support the strategy implementation and change processes. The empirical study has been realized based on the theoretical framework of the diagnostic and interactive management control of Simons (2000) whose main propositions are presented in Table 1. The literature review will help in the interpretation and discussion of the empirical study.

The use of BSC in the diagnostic and interactive mode.

| The use of BSC in DIAGNOSTIC mode to implement the planned strategy | The use of BSC in INTERACTIVE mode to test and review strategy, to identify and facilitate the emergence of new strategies |

|---|---|

| ● The strategy is planned and communicated to the structure ● Managers involve themselves periodically to monitor the execution level of strategy ● Periodically, managers: - Define and negotiate goals - Receive and review performance reports - Analyze deviations - Meet to evaluate and discuss progress in strategy execution Management by Exception | ● The strategy is developed with the contribution of managers ● Strong involvement in the phase of strategic planning; in the communication and decentralization of strategy; and during the execution and monitoring, involving in the decisions of subordinates ● Managers involve regularly and personally in the decisions of decentralized managers: - The information of the BSC is a theme discussed recurrently among managers and subordinates - The system is the organization permanent focus - Senior managers participate in meetings with the subordinates - Permanent debate on information, assumptions and action plans ● Communication and dialog to clarify objectives and strategy ● Discussion and communication along the structure ● Focus on few metrics ● Search for coherence among the components of the strategy map ● Permanent search of new information with the purpose of adjusting current strategy or to define new strategies |

Source: Researchers from compiled evidence.

This investigation adopts an exploratory qualitative case study method to understand how managers, within an organization, use the BSC to support strategy implementation and change processes. The researcher chose the case study method because it provides a better understanding and content theorization of the processes and context in which the practices of management control take place (Berry & Otley, 2004; Berry, Coad, Harris, Otley, & Stringer, 2009).

Research was conducted on two separate moments: a pilot study realized from January to June 2008; and the main study, from July 2008 to June 2009. The study was conducted in a BU of one of the largest Portuguese manufacturing groups that controls industrial and sales operations in 103 different countries. The BU wishes to remain anonymous and will be referred to as Alpha. The company has a 400-employee workforce, generating annual sales in excess of 80 million euros, with foreign markets accounting for more than 85% of total production. Alpha was selected based on its theoretical importance (Yin, 2003). First, the group uses the BSC methodology since 2003, which provided an adequate time frame to study the form of use and impact of the BSC. The adoption of the BSC aimed to assure the alignment of the objectives of management structures and the implementation and monitoring of strategy within each BU. Since then, Alpha managers use the BSC on a rather permanent and dynamic fashion. Second, Alpha has proved significant willingness and interest on the adoption of new management techniques and, particularly, of MC. Third, Alpha is included in one of the largest Portuguese manufacturing groups standing for the business units that operate within context and conditions equivalent to the object of our study (Yin, 2003). Finally, the research reports a successful case in the use of the BSC methodology. The tool was peacefully accepted and integrated into daily routines of the organization by all of the organizational players. The methodology is in use, and general organizational perception is of overall satisfaction. All these reasons led researchers to choose the realization of a unique case study providing deep and detailed descriptions and explanations (Dyer & Wilkins, 1991). Alpha also proved to offer adequate context to the study of the form in which the BSC is used by managers and by the relationship between the BSC and strategy (Keating, 1995).

For data collection, researchers used semi-structured interviews, direct observation, and document collection. Data collection was made during an 18-month period, which allowed obtaining deep knowledge on the culture and management methodologies used in Alpha. Detailed interview was the main data source of this research (Bédard & Gendron, 2004; Mason, 2002), which allowed obtaining detailed and holistic understanding on the experience, opinions, and interviewee attitudes (Mason, 2002; Horton, Macve, & Struyven, 2004; Patton, 1987). Questions were designed in accordance to key theoretical constructs (Patton, 1987; Silverman, 2005; Yin, 2003). Interview scripts were used flexibly in the sense that they were being adjusted as the researchers were proceeding with the interviews (Yin, 2003).

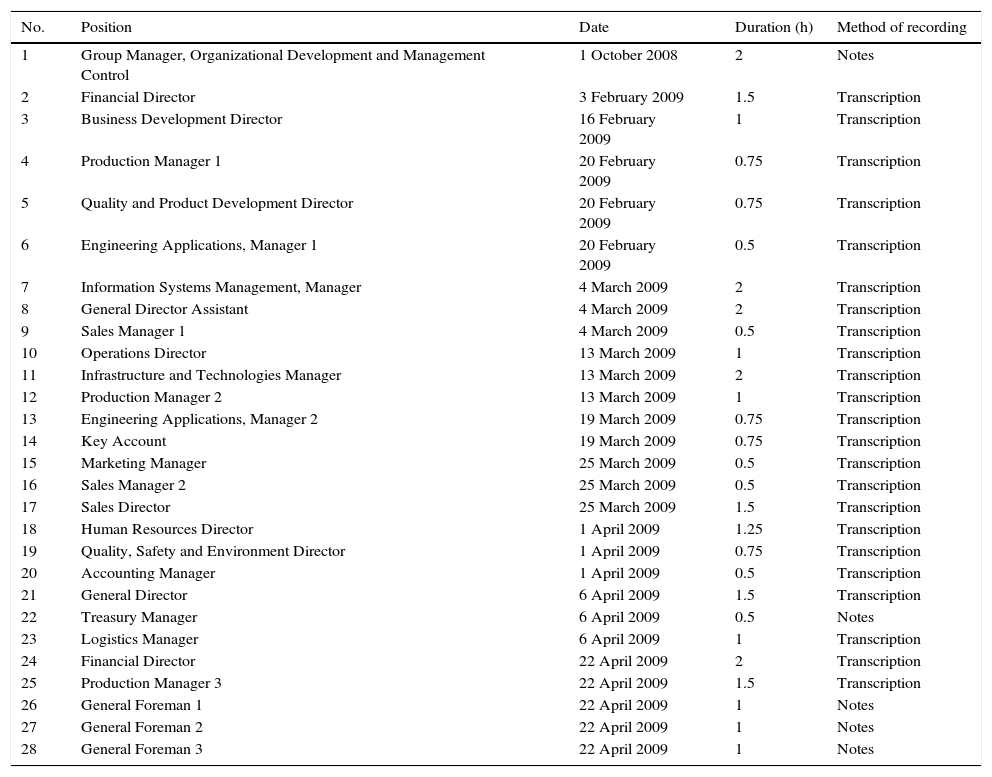

The research study included a total of 28 semi-structured interviews during 30h, representing the major part realized with senior executives. The researcher has not faced significant resistance to recording as managers are used to routine meetings being video and audio recorded. Apart from the interviews, the researcher also interacted with an additional 80 BU employees, of different hierarchical levels, by both mail and directly. Table 2 presents the schedule of interviews that were conducted.After each interview, the researcher filled contact forms where some notes such as date, local, attending people, themes discussed, interviewee's reactions, and unanticipated themes discussed to be included in the following interviews were registered (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Scapens, 2004). As soon as possible, the researchers transcribed the interviews where additional notes were registered (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Moll, Major, & Hoque, 2006; Scapens, 2004; Yin, 2003) and indexed some expressions and interviewees’ behaviors such as pauses, interruptions, tone, emphasis, concordance, and discordance among others (Mason, 2002). The realization of the contact form and the almost immediate transcription of the interviews allowed the researcher to prepare to the following interviews (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Moll et al., 2006). Besides the audio record, the researchers wrote down some notes during the interview that allowed, on the one hand, conducting the interview and, on the other, to help to elaborate the contact forms and in the indexation of interview transcriptions. In the situations in which the researcher has not been authorized to audio record, exhaustive annotations were taken. The analysis of data, resulting from the interviews, was made through the method of content analysis.In the phase of evidence collection, the researchers adopted the following procedures: first, they conducted the maximum number of interviews involving employees of the BU and corporate headquarters; second, the researchers resorted to data and method triangulation; third, they considered the importance of data and sources; fourth, the researchers then resorted to key informers to validate collected evidence and the interpretation that were formulated. Data were coded using the key theoretical constructs (Miles & Huberman, 1994) looking for patterns and exceptions. Still in the analysis phase, the researchers replicated some of the results gathered, through the collection of additional data, and discussed the results obtained with the key informers. The researchers tested the coherence of the results of this case study comparing the results obtained with the results of other investigations on the BSC and on the Simons’ framework. The results were registered in a report, in narrative format, following logic of theory construction (Yin, 2003).

Schedule of interviews.

| No. | Position | Date | Duration (h) | Method of recording |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Group Manager, Organizational Development and Management Control | 1 October 2008 | 2 | Notes |

| 2 | Financial Director | 3 February 2009 | 1.5 | Transcription |

| 3 | Business Development Director | 16 February 2009 | 1 | Transcription |

| 4 | Production Manager 1 | 20 February 2009 | 0.75 | Transcription |

| 5 | Quality and Product Development Director | 20 February 2009 | 0.75 | Transcription |

| 6 | Engineering Applications, Manager 1 | 20 February 2009 | 0.5 | Transcription |

| 7 | Information Systems Management, Manager | 4 March 2009 | 2 | Transcription |

| 8 | General Director Assistant | 4 March 2009 | 2 | Transcription |

| 9 | Sales Manager 1 | 4 March 2009 | 0.5 | Transcription |

| 10 | Operations Director | 13 March 2009 | 1 | Transcription |

| 11 | Infrastructure and Technologies Manager | 13 March 2009 | 2 | Transcription |

| 12 | Production Manager 2 | 13 March 2009 | 1 | Transcription |

| 13 | Engineering Applications, Manager 2 | 19 March 2009 | 0.75 | Transcription |

| 14 | Key Account | 19 March 2009 | 0.75 | Transcription |

| 15 | Marketing Manager | 25 March 2009 | 0.5 | Transcription |

| 16 | Sales Manager 2 | 25 March 2009 | 0.5 | Transcription |

| 17 | Sales Director | 25 March 2009 | 1.5 | Transcription |

| 18 | Human Resources Director | 1 April 2009 | 1.25 | Transcription |

| 19 | Quality, Safety and Environment Director | 1 April 2009 | 0.75 | Transcription |

| 20 | Accounting Manager | 1 April 2009 | 0.5 | Transcription |

| 21 | General Director | 6 April 2009 | 1.5 | Transcription |

| 22 | Treasury Manager | 6 April 2009 | 0.5 | Notes |

| 23 | Logistics Manager | 6 April 2009 | 1 | Transcription |

| 24 | Financial Director | 22 April 2009 | 2 | Transcription |

| 25 | Production Manager 3 | 22 April 2009 | 1.5 | Transcription |

| 26 | General Foreman 1 | 22 April 2009 | 1 | Notes |

| 27 | General Foreman 2 | 22 April 2009 | 1 | Notes |

| 28 | General Foreman 3 | 22 April 2009 | 1 | Notes |

The economic group, to which Alpha belongs, adopted the BSC in 2003. Taking into account the published studies on the adoption of the BSC, the group will have been an early adopter of the BSC in Portugal. The study by Rodrigues and Sousa (2001) concludes that, in 2000, the BSC was not yet a widespread concept in Portugal. Quesado and Rodrigues (2009) also applied a survey to the 250 largest Portuguese companies in 2004 and concluded that, although the companies reported knowing the BSC, their use was still small and recent. Saraiva and Alves (2015) concluded that the introduction of the BSC in Portugal occurred late: in 2000, only 29% of large Portuguese companies used the BSC; in 2004, 29.4%; and in 2009–2010 about 40.9% of companies reported using the BSC.

The decision to implement the BSC at Alpha BU resulted from the need to change, at the time related to the following aspects: (1) the Group's financial performance was not satisfactory; (2) the Group faced strong challenges and uncertainties in the markets in which it operated; (3) an overly traditional and conservative culture has been identified; (4) in 2003, the leadership of the Group was changed and a new governance model was implemented; (5) the form of monitoring of the BUs was considered unsatisfactory; and (6) the Group had no medium-term planning processes, with the budget being the only planning instrument.

The restructure of the Group in 2003 led to the creation of the Organizational Development and Management Control Department, whose role was instrumental in the dissemination and implementation of BSC in various BUs. In 2003, the main objectives of the adoption of the BSC were: (1) to systematize and explain the strategic challenge of the group and each of the BU; (2) operationalize the strategy of each BU; (3) develop a business planning and monitoring model; (4) adopt the same model of management and governance in all BUs; (5) to align the performance management system of managers with the BSC.

Prior to the adoption of the BSC, BUs did not have any strategic planning or evaluation tools for the non-financial performance of their business. The management control system was very budget-oriented and variance calculation. Asked about how to monitor performance in the period prior to 2003, the Financial Director stated that: “We had the budget. And so … from the point of view of structured, constant, systematic evaluation were the goals of the budget and it was based on the budget that we saw if we achieved the results (…). And so there were not many (not to say none!) non-financial metrics that were identified as critical in terms of performance appraisal. It was a more financial issue…” (Financial Director)

Regarding the reasons for the adoption of the BSC, the heads of the BU indicate, on the one hand, the holding company's initiative and, on the other hand, the need for the BU to systematize the strategic planning process and decentralize its operationalization: “The BSC arises from an initiative, by the dynamization of the group. Here is a decision taken at the holding company level, with the General Managers of the BUs, to begin with a process of strategic planning and initiate strategic planning cycles; All this arises in a forum supra BU's.” (General Director). “The motto was to organize our own strategy. It was to systematize everything that was a strategic component of the business or businesses (…) because in fact the tool compelled us to rethink the company's strategy as a team.” (Sales Director)

By appointment and under the guidance of the holding company, all BUs implemented the BSC in 2003, with the support of an external consulting firm. The BSC implementation process was carried out through training and awareness-raising sessions about the tool, its usefulness to the Group and to the BUs, and how to develop the strategic planning process supported by the BSC. The implementation was carried out in a top-down perspective with the involvement of top management bodies of both the holding company and the BUs, which contributed to a rapid involvement and acceptance by the first lines of the structure. On this topic, the General Director of Alpha comments: ”(BSC) arises in a top-down logic with the involvement, the commitment of the BU's, to do anything different in terms of strategic planning.” (General Director)

From 2003 to 2009, the structure and use of the BSC methodology at Alpha have changed. The General Director commented: “This was a long learning process. (…) I do not think I’ve ever been involved in a learning process as long as this. Maybe because it has dimensions beyond the individual; moves with the organization, moves with various levels within the organization; but in fact it is a long process.” (General Director)

The main changes and evolutions in the use of the BSC methodology in Alpha are summarized below:

(1) Synthesis effort in the number of objectives, strategic initiatives and actions

In the early years, the BU adopted a very analytical perspective in building the strategy map and the BSC. This has led to the proliferation of the strategic objectives (between 20 and 30), the strategic initiatives that took place as a breakdown of the objectives (around 80) and operational actions (around 370). This option proved to be difficult to manage and monitor.

The teams involved in the strategy map construction process have been privileging the integrating and structuring objectives of organizational performance, trying to give the strategy map an adequate level of detail. The current strategy map has between 19 and 20 strategic objectives, organized into four perspectives of performance analysis.

The great evolution occurred in the number of strategic initiatives, now seen as major projects of change (and transversal to the organization), and not as a strategic objectives, or as improvement actions, these of recurrent nature and increasingly operational.

On the synthesis effort that has been made during the last years, several Directors commented: ”(…) the whole management has been simplified as much as possible. The number of objectives, the number of strategic initiatives, the breakdown of individual objectives were reduced. All that helped to simplify and brought more clarity to the process.” (Quality and Product Development Director) “When we started this process, also to engage as many people as possible, we had 80 or 90 initiatives, goals, and then we had some difficulty on focus. (…) monitoring all those initiatives was such a great burden, that in the end we did not really follow up, we did not focus and we did not reach the objectives. So we started to focus and try to reduce the number of initiatives to the maximum. And actually, at a given time, we started working eight, nine initiatives and things are going very well right now, and people are focused and that's where they have to go.” (Operations Director) (…) what I noticed at first was that it was very dense, very dull and we apparently committed what are classic mistakes which is to have a set of innumerable initiatives … and then nobody does anything very much with them. Okay, we’ve been through that phase. We had some training on that. We felt obviously that this had no effect and therefore we have much less initiatives nowadays, but we treat things in a more rigorous way.” (Business Development Director)

(2) Population involved in the process of map construction

In 2003 and 2004, the strategic planning process involved a limited number of managers. In 2005, by decision of General Management of the BU, the process was extended to a wider population, which together discussed the strategic objectives and initiatives, and proposed the strategy map. However, the involvement of a large number of managers in the strategy discussion phase made the process inefficient. The Deputy General Manager commented: “A few years ago, (…) we put 10 or 15 people in this room and everyone started talking about the strategic map ‘I think it should be that, it should be that one’. Maybe by then it had to be! Now we think the process should not go there.” (Deputy General Manager).

At present, the process of constructing the strategy map is under the responsibility of the Executive Management, with the decentralization process being carried out by the Executive Managers and those responsible for strategic initiatives (most of them also the Executive Managers) that, together with their teams, identify the actions to execute, resources to deploy, milestones and monitoring mechanisms.

(3) Make the strategic management cycle a continuous process

In the first years of using the BSC methodology, the communication around monitoring was done discreetly and with a large time interval, thus blurring the expected effectiveness of the monitoring and feedback phase. The Sales Director in the USA commented: “The monitoring and communication of progress towards goals and performance was very poor couple of years ago. It is much better now. We look at performance vs. Objectives in the Quadrimester meetings, mid-year and then again at the end of the year. We communicate progress, or lack of progress toward objectives to the other members of the mid-year team and at the end of the 3rd quarter. The communication is much better now.” (Sales Director)

And the General Manager said: “At the outset, the process was becoming more and more difficult, and we only took it for a year and so things had long cycles, they had very long cycles.” (General Director)

Throughout these years, efforts have been made to transform the strategic management cycle into a continuous process, giving higher visibility to the communication of strategy (in the planning phase), involving and aligning the various levels of the structure through alignment sessions, reinforcing the process of “permanent” monitoring at the various levels of the structure, and promoting the creation of inputs and feedback for the next planning cycle.

(4) Conceptual distinction between strategy map and scorecard

The evolution of the use of the BSC methodology, in the BU, and the focus placed on the strategy map (during the planning phase) led to a conceptual separation between the strategy map, understood as a causal diagram containing strategic objectives and the BSC as a set of indicators of the strategic objectives and initiatives that result from the strategy map and are monitored over time. This distinction is visible in terms of internal communication and not so much in the development of the methodology. The strategy map and the BSC do not exist separately, since the BSC indicators are identified from the strategy map.

Currently, the BSC tool, understood more broadly, is used by the BU to support three macro management processes:

- -

Strategic planning, consubstantiated in the construction of the 3-year strategy map, in which the strategic challenge, guidelines, objectives and strategic initiatives are identified;

- -

Communication and decentralization of the strategic objectives and initiatives for the respective Operational Directions and structures. Identification of the actions to be carried out by each area of responsibility, goals, milestones and resources. Alignment of decentralized objectives with the strategic objectives of the BU;

- -

Monitoring of targets, milestones and resources planned for strategic and operational objectives and for strategic initiatives. Feedback for the next planning cycle.

In addition to the BSC methodology, the management control practices in use at Alpha can be summarized in the following: (1) budgeting process, its monitoring and deviation calculation; (2) use of the concepts of industrial contribution margin and commercial contribution margin, both in the budgeting and monitoring phases.

4.2Use of the BSC in diagnosis modelPrescriptive literature and also some empirical studies have stated that performance measurement systems, including the BSC, may be used to support the implementation of strategy. According to the proposition of Simons (1995, 2000), strategy is deliberate, previously planned and communicated to the organizational structure, and managers involve themselves periodically on monitoring the strategy execution level.

In Alpha BU, after formulating/revising and describing the strategy, first-line managers communicate strategy to their employees, negotiate and identify objectives and decentralized actions, and the targets. The objectives and the goals are incorporated in the Individual Objectives Contract (IOC). The monitoring of the IOCs is made through formal controls, with periodical report. Besides the formal monitoring of the IOCs, monthly meetings also take place (Executive Board meetings) with the purpose of monitoring strategic directions, and quarterly meetings to monitor BU and headquarters’ IOCs.

Regarding the IOC, the Financial Director commented: “(.) the practice currently established is, regarding the monitoring of the BU, Executive Board and Sales, people receive from Management Control a monthly status of their objectives. For other departments and remaining employees, it is a quarterly monitoring (…). They receive it by mail. There isn’t any meeting.” (Financial Director)

In addition to this formal monitoring of the IOC, there are also monthly meetings (Executive Board meetings) to monitor strategic direction, and quarterly meetings to monitor IOCs at the BU and holding levels.

This control mode corresponds to diagnosis control mode. This means that the BSC is used by the BU to support the execution of strategy, which has been previously planned and formalized into projects and plans. These results are consistent with former research that analyzed the use of the BSC to implement deliberate strategies (Ahn, 2001; Lipe & Salterio, 2002; Malina & Selto, 2001; Simons, 1995, 2000; Tuomela, 2005; Wijn & Veen-Dirks, 2002).

4.3Use of BSC in interactive modeThe study has shown that from the four strategic control levers indicated by Simons (1995, 2000) it is the interactive mode that prevails in the BU. Evidence has shown that the BSC is used, by top management and executive management team, in an interactive mode.

4.3.1Interactive use of the BSC in the BUAlpha BU adopted the methodology of the BSC in 2003, following headquarters directions. However, evidence revealed that the BSC has not been used to impose the BU a strategy that has been previously formulated by the holding company. On the contrary, the methodology has been used, during the process of strategic planning, to allow for the intervention and contribution of executive managers on the revision, definition and change of the BU strategy, and to prevent the impression that the BU strategy is imposed by the holding. Other studies have demonstrated equivalent results (Jazayeri & Scapens, 2008; Ramos & Hidalgo, 2003; Tuomela, 2005).

One of the results of this investigation is that top management and executive management team use the BSC in an interactive mode. The formulation and revision of strategy is to be made by the executive management team that, in its first stage, involves a larger population to gather contributions for the process of strategic thinking and, in the second stage, leads the revision and definition of strategy-defining objectives and strategic initiatives, setting goals, resources and milestones, identifying owners and relationships among the several components of strategy as well as validating its coherence. Evidence showed that this is a much participated process, supported by discussion and working meetings, and by clarification, brainstorming, and strategic thinking sessions. The structure and consistency of the elements that compose the strategy map helps in the definition, clarification, and description of BU strategy and, therefore, contributes to executive team consensus around strategy.

Monitoring of strategic scorecard is equally achieved with strong involvement of executive managers. Monthly, strategic topics are discussed in executive board meetings, and executive managers evaluate the progress of its objectives and strategic initiatives, discuss action plans and strategic assumptions, and propose new adjustments and new actions to correct previous decisions that are not providing expected results. Evidence also reflected that the use of non-financial indicators helps to identify the problems resulting from threats and strategic uncertainty, and facilitates dialog among managers (Otley, 1999; Simons, 1995, 2000; Tuomela, 2005; Vaivio, 1999, 2004). Board monthly meetings are formal components of control.

As referred previously, the BSC methodology has allowed for a common interpretation of strategy. This is also a facilitator factor of interaction and communication, among managers, in the daily routine. Evidence showed that informal control and strategic dialog are determinant in the form of use of the BSC in the Alpha BU. The interactive use is, many times, supported by conversations and informal discussions that lead to the emergence of new actions or initiatives.

Simons (2000) refers that one of the characteristics of interactive MC is its capacity to generate new initiatives and action plans. Managers should systematically question themselves on: what changed, why it changed, what will be done about that change. The interactive use of MC tools implies adjust the strategies or create emerging strategies, in light of what is routinely going on. In the case being studied, the researcher has verified that executive managers use the methodology of the BSC to raise, within the organization, the emergence of new action plans or strategic initiatives. On the detection and implementation of new opportunities, one of the Directors commented: “(…) there will be a time when an opportunity appears such as Caracole and one says “Look out: this is an exportable thing for the whole world. Let's see what we can do with it? And it becomes the most important!” (…) The detection of the opportunity, its transformation into a strategic initiative, because it generates value. And it generates value internally because it is a value added product; and generates value for the client. And that is clearly how I understand the opportunity of generating new strategic initiatives from our everyday life.” (Business Development Director)

The same director described past situations in which ideas and initiatives have emerged, naturally, from the detection of unexpected opportunities. About a new product, he said: “The example of Caracole is very interesting. Because Caracole is no more nor less than a bag of ordinary cement to which you add cork, you double thermic quantity twofold (…) But if you ask people, they may find they are not part of the strategy decision process but in reality they are. Because for example, Caracole is a good example - Emilia Alves who is the person responsible for the market found an opportunity, exploited the opportunity, gave it dimension and allowed the company, through the mechanisms we have, to multiply this business opportunity. That is a formulation of a strategic initiative! If you ask directly to Emilia if she thinks she participated in the strategy map, I’m not sure she would tell you so. Now, that she clearly participated she absolutely did!” (Business Development Director)

In conclusion, executive managers use the BSC interactively, contributing to the search of new opportunities and detection of threats in a way to adjust existing action plans and/or strategy to new information or realities. Strategy is initially planned keeping room for the incorporation of adjustments or corrections, or even emerging strategies that result from detecting threats or opportunities. Periodically, and according to the annual cycle of strategic management, the strategy is subject to revision. The interactive use of the BSC means that BU Alpha managers use this methodology, not only to support the implementation of the planned strategy, but also to raise, within the organization, the detection of threats and opportunities and the emergence of alerts, new ideas, initiatives, and the correction or adjustment of on-going actions. Results achieved complement research of Tuomela (2005) and Jazayeri and Scapens (2008).

These results counteract the argument of Norreklit (2000) when she defends that the BSC cannot be used interactively because it has a mechanical and hierarchical vision. This study suggests that the interactive use does not depend on the technical characteristics of the tools, in itself, but on the way that the tool is used being consistent with results of former studies (Abernethy & Brownell, 1999; Bisbe & Otley, 2004; Langfield-Smith, 1997; Ramos & Hidalgo, 2003; Tuomela, 2005).

4.3.2BU managers commitment to strategyIn a first stage, the election of executive managers as team leaders for directions, objectives and strategic initiatives seeks to assure their accountability. They lead teams composed of people from several units across different functional hierarchies. The study of De Haas and Kleingeld (1999) showed that one of the consequences of sharing responsibilities, for delivering objectives and goals, is to promote strategic dialog about performance drivers in a language that is perceptible for all managers. Researchers concluded that strategic dialog leads the organization to control strategy collectively and interactively, based on, for example, in the process of double cycle learning. For that reason, the strategic dialog is included within the interactive control mode (Simons, 1995, 2000).

Results of current research are consistent with the study of De Haas and Kleingeld (1999). Evidence suggests that the form of use of the BSC, in the BU of Alpha, promotes the interaction and strategic dialog among the managers of the BU. This is because strategy is defined with their intervention; because strategy understanding is clear and consensual; because the objectives, indicators and goals are perceptible and because managers fell accountable for the delivery of strategy.

This research still showed that the interactive use of the BSC raises the commitment of managers toward strategic goals, validating the research conclusions of Tuomela (2005) but rejects the idea that the discussion around specific metrics, by providing greater visibility on the actions of managers, creates resistance by these. On the contrary, the current research showed consistent results with those of Papalexandris, Ioannou, and Prastacos (2004). The interactive use of the BSC promotes the sharing of information on initiatives and an action carried out by each responsibility area and, often, leads to the emergence of transversal teams that assume collective responsibility to implement initiatives, actions or projects.

4.3.3Involvement of BU managers and strategic learningThe study showed that, for the managers of Alpha BU, the notion of coherence among perspectives and objectives is more relevant than cause and effect relationships. For that reason, the strategy map was successively tuned as managers and organization learned and improved their understanding of the underlying concepts and links among the several components of the tool. The objective, indicators and strategic initiatives have emerged, within the BU, as a result of the learning process. The methodology is used, in the phase of strategy revision, to facilitate discussion and interaction among executive managers, promote the launch of new ideas or strategies, and call on the knowledge on the form in which former strategies have been implemented (learning process).

But the discussion of themes relate with strategy is not limited to the executive board members. Evidence showed that executive managers involve themselves directly in communicating and decentralizing strategic objectives for their functional teams (during the planning phase), and in the follow-up of the execution of the several activities. In the initial stage of the strategic management cycle, the dialog between managers and their subordinates aims to clarify the strategy and the objectives of the BU, of the responsibility areas and people. In the execution phase, the decentralized objectives and resulting actions are themes discussed recurrently between managers and subordinates, in formal meetings or during daily routine interactions. In this phase, managers seek to validate the assumptions and action plans, evaluate the results that are being generated and identify information to adjust actions or the current strategy. First line managers involve themselves in the activities and decisions of their managers, even those that are in the most elementary lines of their hierarchical report. This permanent interaction facilitates learning among the inter relationships among objectives, between operational and strategic objectives, between actions and objectives, between initiatives and objectives. This allows validating the coherence between the various components of the BSC, to gather information for feedback, and to help in the formulation/revision of BU strategy.

Referring to his team, the Sales Director said: ”(…) The objectives are clear, after we convert the objectives into actions (…); people open their own action plans to relate results and objectives; therefore, it leads people to perform their own work plan. (…) and change it, as they evolve in the plan, any plan of action that were previously less well suited to the change that may have occurred in the market. This allows people to see with more anticipation, if what they planned is working or not; if not, I will go other way! Then go to your department head and update the plan. In fact, he is also managing, it feels managing their own risk, manage their own business. It's a bit like that”. (Sales Director)

This research suggests that the methodology of the BSC, used in an interactive mode, raises the decision making power of managers and their commitment toward strategic goals, and promotes strategic learning. These results complement the study of Henri (2006) that concludes that performance measurement systems used interactively favor market awareness, managers’ entrepreneurial mindset, innovation and organizational learning. Also Jazayeri and Scapens (2008) concluded that the performance measurement system that they studied raised the decision making power of managers as well as their accountability level.

4.3.4The role of the BSC in management control systemsAccording to Simons (2000), it is the top managers that select the instruments that management control will use in interactive mode. It is through this instrument that they focus the attention of managers for strategic uncertainties and the need to permanently seek new information in order to adjust the action plans or the current strategy, or launch new actions or strategic changes. In that sense, according to Simons, the management control instrument selected for interactive use is at the center of the MCS. This idea was confirmed by the study Jazayeri and Scapens (2008). In this case study, the selected tool for interactive use is the focus of MCS but that did not excuse the use of other tools: “(…) the BVS is at the centre of the organisation's control system, linking operational practices with strategic intent. And, in addition, it links to budgetary control systems in a productive and complementary manner. (…) the BVS does not stand alone and it seems unlikely that BAE Systems could survive just using a BVS; i.e., without the normal budgetary and reward systems” (Jazayeri & Scapens, 2008: 64).

In the BU, the BSC and information that flows from it are essential parts in the current organization management control. Managers focus on it regularly and an ongoing basis. A Director said: “If this is focus, this is what needs to be in the our daily routine agenda. I believe that it is effectively present. People cannot forget that this is important. It is in this that people need to focus. Without forgetting daily routine. But this is also part of our routine. In other words, this means we have to be focused and always thinking how to achieve this objectives.” (Operations Director)

However, evidence suggests that the budget continues to have a strong predominance while management control tool. One of the first-line managers said: “In truth, I would say that one gives more importance to the budget. However, we cannot ever forget that companies live primarily on their results. (…) the most linear approach to look at results it to check the budget–sales have been reached, results have been achieved; sales targets were not met neither did results. It will not always be like that, obviously, but I would say that, strictly speaking, the budget is always present in the mind of everybody.” (Business Development Director).

Evidence suggests that not all managers have the perception that the budget information stems from strategy and, therefore, from the goals defined in strategic and operational planning phase. Failure of integration between the BSC and the budget is pointed by the general manager itself who, on the connection between the BSC and budget, commented: “It is yet to be properly done. (…) People still do not understand the budget as an implementation plan for 12 months, a thing to three years. (…) One begins to make the process of budgeting a bit away for the rationale (…) of the strategic plan. That link is not yet achieved (…). Neither in the process nor in the people's minds. In neither of the two dimensions. (…) There is a coincidence of timings, there are pasting of information, and it seems that things are achieved, but within the process it is not like that.” (General Director)

The responsible people by the budget referred: “And what happens then is that some issues that are in the strategic map are not in the budget. And then we cannot make it very interactive”. (Information Systems Manager)

Additionally managers also referred that the BSC provides for more flexibility on adapting to context changes, while the budget undertakes higher rigidity on adapting to newer changes.

Concerning the performance management systems (were the bonus systems is included), evidence shows the existence of a strong relationship between the BSC of the business unit and managers’ OICs, at various levels of the hierarquical structure. That integration is clearly perceived by managers.

4.3.5The role of top manager, executive directors and strategy officeThis research showed that there is a strong involvement of the general director in the use of the BSC methodology. The general director uses this system frequently and intensively to communicate objectives and align organization, to promote strategic dialog to secure the ongoing management attention to new strategic initiatives to decentralize and set responsibilities, to monitor, and to promote participation of managers on defining and adjusting their action plans and the generation of ideas. Evidence showed that the engagement of the top manager determines the level of perceived utility by the structure about the use of the BSC. One of the second-line Directors commented: “In the particular case of our General Manager, I think he has a good ability to communicate, get the message through, of engaging people in the objectives.” (Production Manager 3).

And about the ability of the General Director involving the structure in the process, he added: “That cannot be done because, in fact, we produce a map. One can do that with will, involvement and gaining people to the process. And he [the management director] can secure that step. He can gain people that easy.” (Production Manager 3)

Research results show also that the involvement of the General Director contributed for the effective use of the tool. About this issue, the Financial Director referred: “This cannot be disconnected from what you actually do. Because, if beyond this schedule, there is other agenda of “issues that really matter”, then something is wrong (…). And that is the reason why the top sponsorship is key.” (Financial Director)

On the other hand, executive managers are key for the effective use of the BSC. They are key elements in the broadcast and discussion of information related with the BSC methodology, the promotion of meetings and workshops, within their teams to discuss objectives and action plans; in the demand for new opportunities or threats that lead to adjustments to initial assumptions; in the involvement of operational level structure in discussing the issues, that somehow, are strategy related.

The strategy office positions itself as a facilitator of the interactive use of the BSC, namely: to support the collection, organization and availability of information; and boosting the discussion meetings on the level of progress of objectives, initiatives and action plans. One of the concerns raised by the people of the Strategy Office is to assure that the process resulting from the BSC and the resulting information management is simple and accessible to all managers in the BU.

In summary, the evidence suggests that the involvement of top manager is one of the success factors of the use of the BSC methodology, in the BU, and leverages its interactive use. The executive managers are assumed as pivots, the tool of dissemination and proliferation for more operational level, and support the use of the methodology in the interactive form. The strategy office is a process facilitator.

5ConclusionsAlpha was, in 2003, an early adopter of the BSC. The company implemented the BSC with the purpose of aligning the structure and monitoring the strategy of the group. The use and the way Alpha has used the BSC over time has transformed the BSC into a true strategic management tool, used not only to control but also to engage managers and promote strategic feedback and learning.

This study investigated, in depth, the use of the BSC in the four control levers of Simons (2000). In Portugal, there are many studies on the BSC but none has studied the use of the BSC in the light of the Simons’ framework (2000) and in such a detailed way (Saraiva & Alves, 2015).

Our research finds that the BSC methodology may be used under a diagnosis mode to implement deliberated strategies and, simultaneously, under an interactive mode to promote learning, support strategy revision and provide conditions for new strategies. The BSC may still be used to communicate beliefs and boundaries underlying the organization strategic options. This study still showed that the interactive use of MC is not dependent on the features of the technical tools, per se, but on the form in which the tools are used.

The top manager and the executive management team use the BSC on interactive mode, to facilitate the formation of emerging strategies. This is the dominant control lever in the BU. The study has confirmed that the interactive use of the BSC supports the formulation/revision of strategy and the formation of emerging strategies. The strategy map has been tuned, over time, as managers and organization learned and better understood the concepts and links between the several components of the tool. In addition, the methodology can be used to enhance the discussion and interaction between managers, call on the knowledge on the form in which the execution of former strategies have occurred, and promote the launch of new initiatives, action plans, ideas or strategic changes. The permanent interaction boosts the learning on the inter relationships between objectives, between operational and strategic objectives, and between actions/initiatives and objectives. This allows the validation of the coherence between the various components of the BSC, gather information for feedback, and help in the formulation/revision of strategy of the organizations.

The current research confirms the results of former research (Ahn, 2001; Mooraj et al., 1999; Tuomela, 2005) on the use of the BSC to communicate the beliefs and the frontier systems. Evidence has shown that top managers use the BSC to communicate assumed commitment with the stakeholders (the beliefs), through the formalization and communication of mission, strategic challenge, values and critical skills, emphasizing the responsibility that the Organization assumes with their clients, shareholders and employees. Similarly, also the frontiers of strategic action may be communicated through the BSC, through the disclosure of strategic objectives, orientation on the markets and products to develop, and the minimum financial performance to achieve.

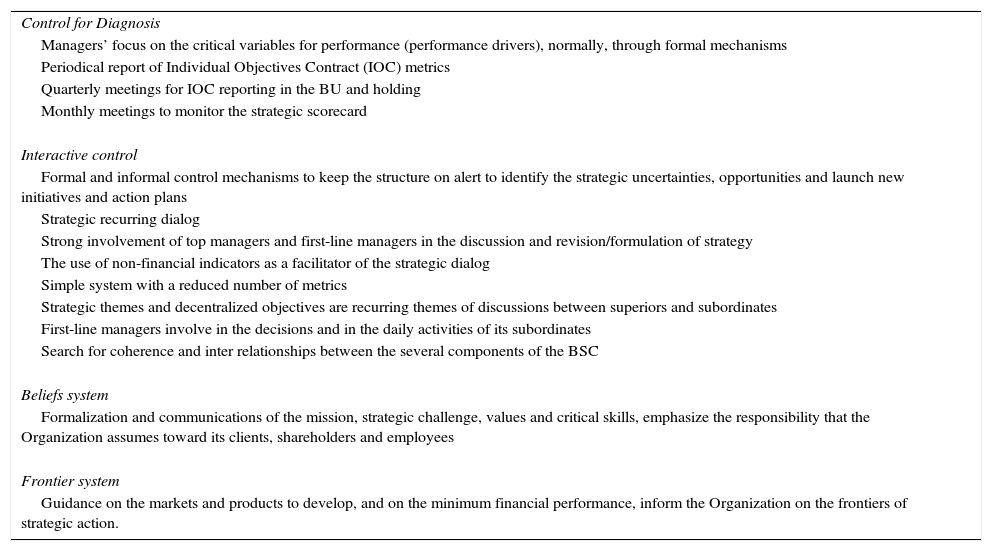

This study allowed the systematization of the characteristics associated to the use of the BSC, in one of the control levers (Table 3).

Links between the BSC and the four control levers.

| Control for Diagnosis |

| Managers’ focus on the critical variables for performance (performance drivers), normally, through formal mechanisms |

| Periodical report of Individual Objectives Contract (IOC) metrics |

| Quarterly meetings for IOC reporting in the BU and holding |

| Monthly meetings to monitor the strategic scorecard |

| Interactive control |

| Formal and informal control mechanisms to keep the structure on alert to identify the strategic uncertainties, opportunities and launch new initiatives and action plans |

| Strategic recurring dialog |

| Strong involvement of top managers and first-line managers in the discussion and revision/formulation of strategy |

| The use of non-financial indicators as a facilitator of the strategic dialog |

| Simple system with a reduced number of metrics |

| Strategic themes and decentralized objectives are recurring themes of discussions between superiors and subordinates |

| First-line managers involve in the decisions and in the daily activities of its subordinates |

| Search for coherence and inter relationships between the several components of the BSC |

| Beliefs system |

| Formalization and communications of the mission, strategic challenge, values and critical skills, emphasize the responsibility that the Organization assumes toward its clients, shareholders and employees |

| Frontier system |

| Guidance on the markets and products to develop, and on the minimum financial performance, inform the Organization on the frontiers of strategic action. |

This work contributed to improve knowledge about the relationship between the BSC and Simons’ framework (1995, 2000). The main theoretical contributions are as follows:

- a)

The interactive use of the BSC does not depend on the technical characteristics, but on the way in which it is used.

- b)

The BSC can be used on the four control levers of Simons (1995a, 2000) but its interactive use has more benefits when compared to its use for diagnostic purposes.

- c)

The study suggests that the interactive use of the BSC increases its effectiveness, measured as the benefits obtained in the processes of strategy management. The main benefits of interactive use of the BSC have been identified:

- -

Increasing managers’ commitment to strategic goals and improving the decentralization process;

- -

Greater sharing of information, knowledge and actions;

- -

Promotes the search for consistency between the components of the strategy with a favorable impact on strategic learning;

- -

Stimulates the strategic management process;

- -

Combats organizational inertia;

- -

In periods of change and/or crisis, it helps to raise the awareness of teams for internal and external difficulties, and to motivate them for decisions and actions that can reduce the impact of these difficulties;

- -

Increases proximity between top managers and the most elementary levels of the organization;

- -

Favors innovation;

- -

Places the organization on permanent alert to identify threats and opportunities;

- -

Encourages the formation of emerging strategies;

- -

It favors the process of change of management control practices.

Interactive use of the BSC has favorable impacts throughout the strategy management process, and is of particular interest to the learning process and strategy review or change. Interactive use raises the creation of emerging strategies.

- d)

This study showed that the interactive use of the BSC incorporates formal and informal control mechanisms. Informal mechanisms are used to monitor but also to promote interaction between managers and to foster the launching of new actions, initiatives or strategies.

- e)

Berry et al. (2009) point out that one of the shortcomings of the Simons’ framework (1995, 2000) is that it focuses only on the role of top managers. This work showed that top-tier managers are key to the BSC being used in an interactive way. They are assumed to be pivots, in the diffusion and proliferation of the tool to the most operational level, and support the use of the methodology in an interactive form.

- f)

Finally, the work developed allowed to identify some of the success factors of the interactive use of the BSC:

- -

Strategic dialog

- -

Informal (other than formal) control mechanisms

- -

Direct involvement of the top manager as a lever for interactive use

- -

Involvement of first-line managers to support interactive use

- -

Function of management control as a facilitator of interactive use

- -

Use of non-financial indicators to promote discussion and interactive use

- -

Ease of access to information

- -

Keep the system simple and accessible to managers.

In light of the fact that the research was supported by a case study, the results that were presented cannot be generalized. Furthermore, and as it was not possible to realize a longitudinal study, the researcher sought to rebuild the historic context and the evolution of the form of use of the BSC, through documental evidence and interviews with some of the actors in the process of adoption of the BSC methodology. So, a retrospective approach was used, asking interviewees to describe and explain former events and current situation.

One of the opportunities for future research is the extension of this research, through a longitudinal study that analyses the evolution and impact of the use of the BSC methodology in Alpha BU. It will also be opportune to replicate this study with regard to other organizations, belonging to the same industry or not, that adopted and uses the BSC. Future research might “test” and develop the results of this research. These studies should provide new contribution to characterize the interactive use of management control practices, identify its success factors, and deepen the role of top managers, management control professionals, and operational managers in the interactive use of control systems. One would suggest that future research focuses on the study of the role assumed by management control professionals and consultants in the implementation and in the form of use of management control practices. In the case presented, the management control professionals prevailed and evidence showed that these assumed a determinant role in the successful use of the BSC in the BU.