This study reports Dutch local government civil servants’ intention to voluntarily leave their current position for various post-exit destinations in times of austerity. It is concluded that local government civil servants’ intention to leave to public sector destinations is determined by their superiors’ quality of leadership (with job satisfaction fully mediating this relation), perceived job security and work-life balance issues (with job satisfaction mediating these relations). For private sector destinations, leadership quality (mediated by job satisfaction) explains intention to leave.

The academic literature has since a couple of decades studied the phenomenon of turnover (or, inversely, retention) intentions and behaviours in public administration (Cho & Lewis, 2012; Lee & Jiminez, 2011; Lee & Whitford, 2007; Meier & Hicklin, 2008; Moynihan & Landuyt, 2008; Selden & Moynihan, 2000; Steijn, 2003). Many studies focus on intention to leave of relatively scarce or specialized employees such as nurses (Homburg, Van der Heijden, & Valkenburg, 2013; Van der Heijden, Dam, & Hasselhorn, 2009) or ICT professionals (Kim, 2005). This article reports on a study of general municipal civil servants’ intention to leave their current position or organization in the Netherlands. There are a number of circumstances or features that justify this particular study, and makes it different from existing studies reported in the literature.

First of all, this study does not explain an employee's more general intention to leave, but rather seeks to explain an intention to leave for specific post-exit destinations (such as other municipalities, other public sector organizations, private sector organizations including consultancy firms), with possibly various determinants accounting for various post-exit destinations.

Second, many turnover studies report on turnover intentions of relatively specialized employees in tight market conditions, resulting in labour shortages. This particular study inversely reports on civil servants’ intention to leave in a context of both austerity as well as increasing work loads. These circumstances result from the implementation of the so-called 3-D decentralization programme (Allers & Steiner, 2015), in a context in 2013 in which municipalities had to compensate for a general deficit of 2.7 billion euros, reductions in budgets resulting from decentralizing budgets of 2.9 billion euros, and miscellaneous deficit-reducing measured of 0.5 billion euros, accounting for a total budget cut of 17% of net expenditures and decentralization tasks (Allers, Steiner, Hoeben, & Geertsema, 2013; Allers & Steiner, 2015).

Third, this study addresses the issue of performance-related (merit) pay in the public sector. The academic literature, as well as policy practice talks about positive and negative consequences of performance-related pay. In this study, it is explicitly analysed whether there is a relation between preference for performance-related pay and turnover intentions to specific post-exit destinations, thus adding to the general debate.

Fourth, the focus is on explaining public sector employees that may or may not decide to leave a particular type of public sector organizations, that is, municipalities in the Netherlands. Municipalities are an important employer in the local labour market. All municipalities taken together are the largest employer in the Dutch public sector, accounting for more than 50% of all public sector employment (excluding educational institutions, defense and policing) (Allers et al., 2013).

In sum, the research question for this study is how envisaged municipal civil servants’ post-exit destinations can be explained. The article is structured as follows. In the next section, we report on a literature review on turnover intentions in the public sector and derive and formulate various hypotheses. We then report on the data used and the design of the empirical study of turnover intentions of local government employees working for middle-sized municipalities in the Netherlands, and report on the choice of measures (operationalisations) used. Subsequently, we report the empirical findings and test a model of how various determinants may influence turnover intentions to specific post-exit destinations. We end the article with conclusions and implications of the findings for research and HRM practice.

2Literature review and hypothesis2.1Management and leadershipOne of the most recurrent themes in explanatory studies of employees’ turnover intentions is the role of management and leadership. A substantive argument for this expectation is that supervisors with adequate leadership skills and management qualities provide social support for employees facing stress and uncertainties in their work (Homburg et al., 2013; Nissly, Barak, & Levin, 2008; O’Driscoll & Beehr, 1994; Van der Heijden et al., 2009), which may prevent these employees from leaving the organization. For this study, we hypothesize that employee perceptions of management and leadership qualities impact on their intention to leave the organization, and this expectation is formulated in Hypothesis I.Hypothesis I The more satisfied employees are with management and leadership quality, the less is their ‘intention to leave’.

An intuitively appealing and empirically validated determinant of intention to leave is satisfaction with pay and benefits (Cho & Lewis, 2012; Homburg et al., 2013; Lee & Jiminez, 2011; Lee & Whitford, 2007; Llorens & Stazyk, 2011; Moynihan & Landuyt, 2008; Pitts, Marvel, & Fernandez, 2011; Steijn, 2003; Van der Heijden et al., 2009). Pitts et al. (2011) note that the impact of satisfaction with pay and salaries dampens throughout the career, with young employees being very sensitive towards displaying an intention to leave as a result of dissatisfaction with pay and benefits, and more mature employees not reacting to dissatisfaction with pay and benefits by means of considering leaving the organizations. For the explanation, we hypothesize that satisfaction with pay and benefits negatively impacts on employees’ intention to leave. This relation is formulated in Hypothesis II.Hypothesis II The more satisfied employees are with pay and benefits, the less is their intention to leave.

Kellough and Osuna (1995) reported that organizations with greater room for promotion tend to display lower turnover (Homburg et al., 2013; Iverson & Pullman, 2000; Selden and Moynihan, 2000). The hypothesis that career development opportunities reduce intention to leave, has received mixed empirical support, and hence various interpretations. Curry, McCarragher, and Dellmann-Jenkins (2005) report that meeting employee expectations results in retention, whereas Ito (2003) argues that investment in development opportunities increases candidates’ employability, possibly increasing the likelihood that they will opt for extramural career opportunities (Kim, 2005).

In this article, we conceptualise career development opportunities as an employee's individual perception of chances for individual promotion and development (rather than a feature of HRM policies), and we follow the line of reasoning that an employee that faces career development opportunities is more likely to stay than an employee that does not (since the latter may be more tempted to consider leaving the organization). This line of reasoning is expressed in hypothesis III.Hypothesis III The more satisfied employees are with career development opportunities, the less is their ‘intention to leave’.

A large strand in the literature that attempts to explain turnover has to do with work-to-home interference and home-to-work interference (den Dulk & Groeneveld, 2013; Moynihan & Landuyt, 2008). We expect that the more satisfied employees are with ways in which they are able to manage work-life issues (whether or not because of specific family-friendly policies and practices), the less they will display an intention to leave. This relation is formulated in Hypothesis IV.Hypothesis IV The more satisfied employees are with work-life balance issues, the less is their ‘intention to leave’.

Performance management is one of the key ingredients of the new public management that has, since a couple of decades, invaded the public sector in the Western world and beyond (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2011; Pollitt, Van Thiel, & Homburg, 2007). Part of these management ideas and practices is ‘incentivization’ of human resources management: the basic idea that in order to motivate employees and secure both individual performance as well as organizational performance eventually, public managers must link outcomes that workers value (for instance, pay and salaries) to performance (Lee & Jiminez, 2011). One solution to achieve this is to design a contract that provides financial incentives for employees not to resort to shirking but rather to deliver the outputs that are explicitly required from them as stated in specific written or informally agreed-upon arrangements. Related to the issue of turnover and retention, empirical research has provided support for the hypothesis that higher salaries encourages employees to stay in the current workplace (Moynihan & Landuyt, 2008), with supervisory- and management-level employees being more sensitive towards performance-related incentives than lower-level employees are. Lee and Jiminez (2011) conclude that the existence of performance-based management practices, specifically performance-based rewards and – supervision, promotes ‘loyalty’.

At the moment of the research, the municipalities under study did not provide performance-related financial incentives. Given the theoretical lines of reasoning and empirical evidence provided in various studies, and given the current absence of performance-related pay practices, we hypothesize that employees who prefer, all other things being equal, performance-related pay, have a higher intention to leave than employees who do not prefer performance-related pay. This basic hypothesis is formulated as Hypothesis V.Hypothesis V The more employees prefer performance-related pay, the more is their ‘intention to leave’.

In our analysis we follow Sverke (2004) in assuming that perceived job insecurity impacts on an individual worker's intention to leave the organization, suggesting that workers may proactively anticipate on reorganizations and possibly losing their job by means of considering leaving the organization (Greenhalgh & Rosenblatt, 1984). This line of reasoning is formulated in Hypothesis VI.Hypothesis VI The more employees face job insecurity as a result of upcoming reorganizations, the higher is their ‘intention to leave’.

In our model, we assume that the hypothesized determinants mentioned above do not directly impact on the eventual dependent variable intention to leave, but rather have an effect on an individual worker's perceived job satisfaction, which is assumed to mediate the relations between the various determinants on the one hand and the dependent variable ‘intention to leave’ on the other hand (Mobley, 1977). In other words, we assume a pivotal role for job satisfaction, meaning that the determinants mentioned above have a profound effect on an individual's job satisfaction, and a diminished job satisfaction is the prime explanation of a person's intention to leave the organization. This line of reasoning is formalized with Hypothesis VII.Hypothesis VII The relations between the various determinants of ‘intention to leave’ and ‘intention to leave’ are mediated by job satisfaction.

The data source used for this research was a survey among employees of middle-sized municipalities in the Netherlands, administered during the implementation of the 3D-decentralization programme in 2013. We consulted executive managers of six specific yet relatively comparable municipalities in the same southwest region in the Netherlands (Hellevoetsluis, Goeree-Overflakkee, Maassluis, Krimpen aan den IJssel, Midden-Delfland and Druten) and asked them to distribute invitations to complete a 23-item web based questionnaire among their subordinates. This resulted in 240 completed questionnaires (a response rate of 58%, varying from 48% to 85% for the various participating municipalities) and 42 questionnaires which were entered from beyond this sample, resulting in a total response of 282 completed questionnaires. The target population was the set of employees working in functions that require a (completed) Bachelor degree (or higher) in either higher vocational education or University education. The choice to limit the data gathering to highly educated employees was informed by the fact that, according to Moynihan and Landuyt (2008), this group has a greater ability to gain alternative employment than other groups of employees, and thus are more likely to display an intention to leave. In the Dutch labour market, unemployment levels of highly educated employees (3.4% of the working population) is typically lower than unemployment levels of middle (8.8%) and lower educated employees (15.7%) (UWV, 2013).

3.2Measurement of intention to leaveThe dependent variable in this study is the ‘intention to leave’ for a specific post-exit destination. ‘Intention to leave was measured using a series of five items taken from Homburg et al. (2013), adjusted to various post-exit destinations like (1) another department in the same organization, (2) another municipality, (3) within another public sector organization, (4) outside the public sector and (5) working as a self-employed contractor. The preference for specific destinations was measured using a rating scale from 1=never to 4=various times per week. A sample item was: ‘how often do you think about leaving to another department in the same organization?’.

3.3Measurement of satisfaction with management and leadership qualitySatisfaction with management and leadership quality was measured using two scales. The first scale assessed quality of leadership using four items taken from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) developed by Kristensen (2000). Responses were made on a five-item rating scale. A sample item was: ‘to what extent would you say that your immediate superior makes sure that the individual member of staff has good development opportunities’. The second scale assessed social support from the supervisor using four items from Van der Heijden et al. (2009). A sample item was: ‘is your immediate supervisor able to appreciate the value of your work and its results?’. Responses were also made on a five-item rating scale; the first three items on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (often) and the last question on a scale from 1 (‘shows little willingness to help me’) to 5 (‘is very willing to help me’).

3.4Measurement of satisfaction with pay and benefitsSatisfaction with pay and benefits has been measured using two scales developed by Hasselhorn, Tackenberg, and Müller (2003) and Howard (1999). Three items taken from Hasselhorn et al. (2003) are related to satisfaction to pay. A sample item was: ‘how satisfied are you with your pay in relation to your need for income?’ Responses were made on a five-item rating scale. The four items taken from Howard (1999) are related to secondary benefits measured on a five-item rating scale. A sample item was: ‘how satisfied are you with your benefits package?’.

3.5Measurement of satisfaction with career development opportunitiesSatisfaction with career development opportunities was measured using three items taken from Horn (1983). Responses were made on a two-item rating scale.

A sample item was: ‘Within a few years I expect to have a higher position in this organisation’.

3.6Measurement of satisfaction with work-life balanceThe scale for assessing participants’ satisfaction with work-life balance was taken from Netemeyer, Boles, and McMurrian (1996) using two scales on work-family conflicts and family-work conflicts, resulting in ten items on a five-item rating scale. A sample item was: ‘the demands of work interfere with my home and family life’.

3.7Measurement of preference for performance-related payFor the measurement of performance-related pay eight items on a four-item rating scale were taken from Poppe (2012) specifically developed for measuring the preference for performance-related pay. As performance-related pay is not yet implemented in the public sector as it is applied in the private sector, the presence or absence of performance-related pay in relation to intention to leave could not be measured in this study. Therefore this study is limited to examining the preference of performance-related pay. A sample item was: ‘I prefer to get paid for my performance’.

3.8Measurement of job insecurityJob insecurity was measured using five items from Sverke (2004). Responses were made on a five-item rating scale. A sample item was: ‘I’m afraid I will lose my job’.

3.9Measurement of job satisfactionJob satisfaction was measured by four items from Kristensen (2000) and Allen and Meyer (1990), on a four-item rating scale. A sample item was: ‘How satisfied are you with work conditions generally?’

4Results4.1Descriptive statisticsThe mean scores, standard deviations, correlations, as well as the Cronbach's alpha values for the scales used are reported in Table 1. The general score on ‘Intention to leave’ (encompassing all possible post-exit destinations) is just below the theoretical mean of 3 on a five point Likert-scale. Here, the main effect of the municipality respondents were employed by was not significant F(5, 235)=.299, p=n.s.).

Means, standard deviations, Cronbach's α and correlations of study variables.

| Mean (SD) | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 46.9 (14.5) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Gender (1=female) | 0.42 (0.49) | −.117 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 3. Quality of leadership (1–5) | 3.17 (0.80) | 0.83 | −.072 | −.069 | 1 | |||||||||

| 4. Social support (1–5) | 3.45 (0.76) | 0.83 | −.048 | .001 | .646** | 1 | ||||||||

| 5. Satisfaction salary (1–5) | 3.32 (0.90) | 0.90 | .097 | −.041 | .369** | .232* | 1 | |||||||

| 6. Pay and benefits (1–5) | 3.35 (0.77) | 0.94 | −.036 | .005 | .264** | .215** | .392** | 1 | ||||||

| 7. Career development (1–2) | 1.86 (0.27) | 0.75 | −.230** | −.010 | −.238** | −.196** | −.067 | −.116 | 1 | |||||

| 8. Work-life balance (1–5) | 1.68 (0.57) | 0.88 | −. 015 | −.081 | −.113 | −.068 | −.169** | −.066 | .067 | 1 | ||||

| 9. Job satisfaction (1–4) | 2.94 (0.53) | 0.79 | .072 | −.032 | .456** | .368** | .283** | .220** | −.123** | −.231** | 1 | |||

| 10. Job security (1–5) | 3.51 (0.98) | 0.89 | .062 | .062 | .068 | .060 | .025 | .11* | −.133** | −.171** | .194** | 1 | ||

| 11. Merit pay preference (1–4) | 2.86 (0.59) | 0.91 | −.029 | −.163** | −.073 | .026 | −.197 | −.076 | −.045 | .070 | −.036 | .155* | 1 | |

| 12. Intention to leave (1–5) | 2.35 (1.09) | 0.78 | −.101 | .049 | −.413** | −.261** | −.202** | −.183** | .150* | .226** | −.557** | −.090 | .135* | 1 |

The dependent variable intention to leave is correlated with quality of leadership (r=−.413, p<0.01), social support (r=−.261, p<0.01), satisfaction with salary (r=−.202, p<0.01), satisfaction with pay and benefits (r=−.183, p<0.01), career development (r=.150, p<0.05), work-life balance (r=.226, p<0.01), job satisfaction (r=−.557, p<0.01), job and merit pay (p=.135, p<0.05), but not with job security (r=−.090, n.s.).

Table 2 reports the post-exit destinations of choice. Most favourite destination is another municipality (49.6% thinks about this career option once a year or more), followed by another public sector organization (not being a municipal organization, 44.7%), private sector generally (44.3%), another department in the current municipality (29.1%), with becoming self-employed contractor being the least preferred destination (25.9%) generally. As we are concerned with the intention to actually leave the organization, in the analysis we are only focusing on turnover intentions to extramural public sector destinations (other municipalities or other public sector organizations) and to extramural private sector destinations (such as private sector organizations, or becoming a self-employed contractor).

Preferred post-exit destinations.

| Post-exit destination | Never | A couple of times yearly | A couple of times monthly | A couple of times weekly | More than a couple of times yearly |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intramural | |||||

| Other department | 70.9% | 23.8% | 3.5% | 1.4% | 29.1% |

| Extramural | |||||

| Other municipality | 50.4% | 37.2% | 37.2% | 10.3% | 49.6% |

| Other public sector organization | 55.3% | 32.3% | 8.5% | 3.5% | 44.7% |

| Private sector | 55.7% | 32.6% | 8.9% | 2.8% | 44.3% |

| Self-employed contractor | 74.1% | 16.7% | 3.5% | 4.6% | 25.9% |

The general intention to leave is described by the frequency of reported thoughts on leaving the organization or position (see also Table 2). Eventually, the intention to leave-scales were recoded into binary variables (0=never, 1=at least once a year), to be able to carry out a logistic regression analysis.

4.2Hypothesis testing4.2.1Procedure and model assumptionsThe hypotheses were tested by means of logistic regression analysis. In general, logistic regression models predict the probability of an event Yi (in this case, the probability of a municipal civil servant expressing an intention to leave for a post-exit destination) by means of independent variables that are binary, categorical or continuous (Pampel, 2000). In order to test the hypothesized influence of quality of leadership social support, satisfaction with salary, satisfaction with pay and benefits, career development, work-life balance issues, job security and preference for merit pay on intention to leave with job satisfaction acting as mediator, we employed the steps put forward by Baron and Kenny (1986) for each of the envisaged post-exit destinations. For (1) public sector and (2) private sector extramural post-exit destinations, we first regressed intention to leave against the hypothesized determinants (excluding job satisfaction). Second, we regressed the determinants against job satisfaction. Third, we regressed job satisfaction and intention to leave; fourth and finally, all determinants including job satisfaction were regressed against intention to leave.

All analyses were carried out with gender (Lee & Whitford, 2007) and organizational experience (Moynihan & Landuyt, 2008) as control variables.

4.2.2Hypotheses with respect to envisaged public sector post-exit destinationsThe results of the hypothesis-testing procedures for public sector post-exit destinations are described in Tables 3–5. It can be concluded that work-life balance issues and job security are correlated with intention to leave, both in the absence as well as in the presence of job satisfaction as hypothesized determinant of intention to leave (note that in the analysis where intention to leave is regressed with various determinants, Nagelkerke's R2 increases from .263 to .314 when job satisfaction is included as predictor). Quality of leadership, on the other hand, is positively correlated in the absence of job satisfaction, but not correlated in the presence of job satisfaction. It is therefore concluded that the relation between quality of leadership and intention to leave for a position in the public sector is fully mediated by job satisfaction. The relations between work life balance and job security, respectively, are partially mediated by job satisfaction. We conclude that Hypotheses I, IV and VI are supported, with partial support for Hypothesis VII in the sense that job satisfaction fully mediates the relationship between quality of leadership and partially mediates the relation between job security and work life balance on the one hand and intention to leave on the other hand.

Logistic regression analysis for intention to leave for an envisaged public sector post-exit destination, with controls, without job satisfaction and with job destination as a predictor [Baron and Kenny (1986) steps 1 and 4].

| Model 1 B (SE) | Model 2 B (SE) | Model 3 B (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | .637 (.458) | .625 (2.020) | 2.859 (2.215) |

| Gender | .008 (.277) | .084 (.317) | .099 (.326) |

| Organizational experience | −.030 (.012)* | −.031 (.014)* | −.032 (.014)* |

| Quality of leadership | −.629 (.271)* | −.420 (.282) | |

| Social support | .040 (.258) | .121 (.265) | |

| Satisfaction with salary | −.195 (.190) | −.152 (.195) | |

| Satisfaction with pay and benefits | .195 (.216) | .244 (.222) | |

| Career development | .054 (.562) | .178 (.570) | |

| Work-life balance | 1.024 (.283)** | .898 (.293)** | |

| Job security | −.418 (.172) * | −.461 (.180)* | |

| Merit pay preference | .447 (.272) | .563 (.289) | |

| Job satisfaction | −1.162 (.380)** | ||

| Nagelkerke R2 | .038 | .263 | .314 |

Linear regression analysis for job satisfaction [Baron and Kenny (1986) step 2].

| Model 1 B (SE) | Model 2 B (SE) | |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | 2.956 (.120) | 1.789 (.416) |

| Gender | −.038 (.073) | −.038 (.065) |

| Organizational experience | .003 (.003) | .003 (.003) |

| Quality of leadership | .209 (.054)** | |

| Social support | .086 (.052) | |

| Satisfaction with salary | .049 (.039) | |

| Satisfaction with pay and benefits | .040 (.044) | |

| Career development | −.030 (.119) | |

| Work-life balance | −1.52 (.055)** | |

| Job security | .024 (.034) | |

| Merit pay preference | .050 (.056) | |

| R2 | .007 | .272 |

Logistic regression analysis for intention to leave [Baron and Kenny (1986) step 3].

Tables 6–8 describe the results for the hypothesis testing with respect to intention to leave to an envisaged private sector post-exit destination. Generally, it can be concluded that quality of leadership's relation with an intention to leave to a private sector post-exit destination is fully mediated by job satisfaction (Nagelkerke's R2 increases from .201 to .319 when job satisfaction is included as predictor, and after inclusion of job satisfaction quality of leadership does not correlate with intention to leave any more), whereas career development impacts significantly with intention to leave, both directly (negatively) as well as mediated by job satisfaction. For envisaged private sector post-exit destinations, Hypotheses I and III are supported, with partial support for Hypothesis VII with respect to quality of leadership (full mediation) and career development (partial mediation).

Logistic regression analysis for intention to leave for an envisaged private sector post-exit destination, with controls, without and with job destination as a predictor [Baron and Kenny (1986) step 1 and step 4].

| Model 1 B (SE) | Model 2 B (SE) | Model 3 B (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | .274 (.455) | −1.764 (1.996) | 1.642 (2.234) |

| Gender | −0.181 (.278) | .302 (.305) | .326 (.325) |

| Organizational experience | −.032 (.012)** | −.034 (.013) ** | −.034 (.014) ** |

| Quality of leadership | −.528 (.259) * | −.217 (.275) | |

| Social support | .308 (.249) | .472 (.266) | |

| Satisfaction with salary | −.124 (.184) | −.072 (.199) | |

| Satisfaction with pay and benefits | −.234 (.210) | −.205 (.224) | |

| Career development | 1.184 (.567) * | 1.265 (.583) * | |

| Work-life balance | .433 (.264) | .202 (288) | |

| Job security | −1.96 (.159) | −.250 (173) | |

| Merit pay preference | .502 (.262) | .666 (.290) * | |

| Job satisfaction | −1.773 (.402)** | ||

| Nagelkerke R2 | .048 | .201 | .319 |

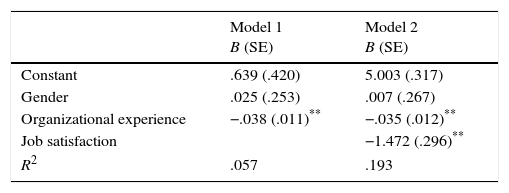

Logistic regression analysis for intention to leave [Baron and Kenny (1986) step 3].

Results hypotheses testing.

| Hypothesis (determinant) | Conclusion public sector post-exit destinations | Conclusion private sector post-exit destinations |

|---|---|---|

| The more satisfied employees are with management and leadership quality, the less is their ‘intention to leave’ | Supported | Supported |

| The more satisfied employees are with pay and benefits, the less is their intention to leave’ | Not supported | Not supported |

| The more satisfied employees are with career development opportunities, the less is their ‘intention to leave’ | Not supported | Not supported (significant and partially mediated by job satisfaction, but sign is reversed) |

| The more satisfied employees are with work-life balance, the less is their ‘intention to leave’ | Supported | Not supported |

| The more employees prefer performance-related pay, the more is their ‘intention to leave’ | Not supported | Not supported |

| The more employees face job insecurity as a result of upcoming reorganizations, the higher is their ‘intention to leave’ | Supported | Not supported |

| The relations between the various determinants of ‘intention to leave’ and ‘intention to leave’ is mediated by job satisfaction | Supported for full mediation (quality of leadership), partial mediation (work life balance, job security) | Supported for full mediation (quality of leadership) |

A better understanding of the factors underlying public sector officials’ considerations to voluntarily leave the municipal organizations in times of austerity may prove to be essential in order to meet the requirements and demands of the public sector of the future, which is momentarily being reshaped as austerity, as well as organizational demographics (i.e., an ageing workforce in the public sector) are on the agenda of public sector HRM professionals.

The conclusions add to the literature on turnover and public sector HRM in a number of ways.

First, this study documents that there is a considerable intention to leave among municipal civil servants in the Netherlands, with another department, another municipality, another public sector organization and private sector organization as almost equally popular post-exit destinations. Public sector employees both consider private sector as well as public sector destinations, with various determinants explaining the choice for either of the two destinations.

Second, based on the analyses, we can conclude that quality of management and leadership impacts job satisfaction and intention to leave for both public and private sector post exit destinations; public sector post exit destinations are furthermore explained by job security and work-life balance issues, whereas private sector destinations are also explained by career development issues (Boyle, Bott, Hansen, Woods, and Taunton, 1999; Gerstner & Day, 1997; Homburg et al., 2013). This particular result suggests that employees who perceive development opportunities prefer to exploit them in the private sector (Ito, 2003; Kim, 2005). Obviously, investments in career opportunities and prospects in order to retain valuable members of staff may turn out to be a risky venture, as investments in individuals seem to boost their employability more than their organizational loyalty and commitment.

Third, another striking finding is that there is a limited role for financial aspects in explaining an individual's intention to leave. Dissatisfaction with one's current salary and benefits, nor preference for performance related pay, explain an intention to leave the organization. Obviously, the individual members of the target population are less inclined to base their career development considerations on financial matters than could be expected (Cho & Lewis, 2012; Lee & Jiminez, 2011; Lee & Whitford, 2007; Llorens & Stazyk, 2011; Moynihan & Landuyt, 2008; Pitts et al., 2011; Steijn, 2003) and rather take into account work-life balance issues, career prospects, and job security issues. We found that respondents did express a preference for more performance-related forms of payment yet it did not explain intention to leave to either other public sector organizations, nor to private sector organizations. This can possibly be explained by the fact that performance-related pay is not yet introduced in the public sector as applied in the private sector. Also, in the Netherlands as in many other countries, secondary benefits (pensions, paid leave, etc.) in the public sector are overall more generous than comparable benefits in the private sector, which can contribute to employees’ retention in the public sector. This finding is very relevant in discussions on incentivization of public sector labour conditions, and application of performance-related pay schemes in the public sector.

The findings of this study should be interpreted in the light of several limitations. First, although measures have been taken into account to ex-ante and ex-post check for common method bias, the use of self-reported variables makes the study vulnerable to the accusation that such a bias did affect our findings. Second, the dependent variable is a perceptual measure (a choice which has been made based on practical and theoretical arguments, see introduction) whereas it might also be interesting and relevant to carry out comparative research among respondents who either change jobs quickly and frequently, and among respondents with relatively long organizational careers, enabling the testing of hypotheses concerning turnover behaviours instead of turnover intentions. Third, we are aware of the fact that our sample consists of municipal public officials from only six middle sized Dutch municipalities and generalization of findings requires a more diverse and possible international or comparative sampling. Fourth, and partly taking up on the third limitation, the population of this study consists of relatively highly educated employees, who, according to Moynihan and Landuyt (2008), are more prone to turnover intentions (and possibly turnover behaviours). Therefore, the turnover intentions reported in this study are likely to be somewhat overestimated.

Following up on the conclusions and limitations, it is possible to identify both lessons for practitioners as well as for future research endeavours.

For practitioners, it should be clear that both in the general literature, as well as in this particular study, intention to leave voluntarily is best explained by non-monetary variables like management and leadership quality and job satisfaction, rather than by satisfaction with pay and benefits and preference for merit pay. Obviously, for practitioners wishing to commit current employers in municipalities, it ‘pays’ to invest in management and leadership quality, rather than in monetary incentives. A second insight for practitioners is that committing employees by offering career development opportunities is a risky business: employees perceiving career development opportunities are more likely to pursue those opportunities elsewhere, rather than in the current organization or position.

For researchers, other opportunities can be identified.

First, a striking conclusion is that preference for performance related pay in general does not impact a person's intention to leave. However, this finding might be moderated by an employee's stage in his or her career, age, personal circumstances and/or professional background. For instance, the relation between incentives and turnover intentions might be stronger for employees having a professional background in economics (compared to employees having other professional backgrounds, such as engineering, social work, or legal professionals). Additionally, employees’ career stage could also moderates the relation between incentives and turnover intentions, reflecting a greater need for financial resources by, for instance, employees starting up families, as opposed to senior employees with less family commitments. These considerations might lead to a hypothesis like the relationship between an employee's preference for performance related pay and their intention to leave is moderated by the employees’ career stage and by the employee's professional background.

Second, this study has explained a self-reported intention to leave one's current position or organization. Although in the literature it is reported that intention to leave and actual turnover are highly correlated, it might be worth investigating actual turnover behaviours using longitudinal data sets rather than cross sectional analyses of intentions to leave. Although there are ample opportunities and difficulties in composing datasets as to enable such studies, future researchers might be willing to discover and explain actual career paths from municipal civil servants, with various determinants possibly explaining retention, and actual (vice versa) cross-over careers between public and private sector. In such a way, possibly stereotypes of municipal civil servants’ never ending loyalty, as well as private sector employees assumed ignorance of career opportunities in the public sector, could eventually either be validated or nuanced based on empirical observations rather than mere talk.