The main objective of this study was to determine whether the adoption of e-commerce in Colombia presents problems of social massification; specifically, we wanted to verify whether the socioeconomic variables and level of education have a moderating effect on the adoption of electronic commerce. An empirical study was conducted, 936 surveys were collected through a form on the Web, the data were analyzed and a prediction was made of the model using the PLS technique. The results confirm in an exploratory way this moderating effect of the socioeconomic and educational level on the relationship between the variable conditions that facilitate electronic purchasing. The main contribution to the theory of these findings empirically validates that, in countries with high levels of social inequality, the use of e-commerce is conditioned by the socioeconomic and educational characteristics of those who can access it.

The Internet has transformed the social and economic relations of the 21st century, and part of this change has been generated in commerce; the classic distribution channels are being displaced by or shared with this new virtual channel (Agudo-Peregrina, Pascual-Miguel, & Chaparro-Peláez, 2014).

Studies have confirmed that electronic commerce offers different advantages to buyers with respect to physical stores and that the purchase motives include personality traits such as feelings, beliefs, pleasures, fun, taste for new technologies and a low price search. Along with the influence of social and external factors and the characteristics of the purchasing system and the Internet (Sánchez-Torres & Arroyo-Cañada, 2016; Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, & Davis, 2003), few studies have described these dynamics in developing countries (Mesías, Sánchez-Giraldo, & Ballesteros-Díaz, 2011).

The degree of development in the adoption of electronic commerce at the global level presents differences depending on the region, especially in Latin America and the Caribbean, where there are delays in the development of the infrastructure and the adoption of Internet services, in the deployment of high-capacity transmission, in offering access to services and quality at affordable prices, and in expanding access to poorer or more remote regions and populations (Katz, 2015). All these issues contribute to the great “digital gap”, which is the measure of inequality between countries in the access to and use of new communication technologies, such as the Internet and mobile phone; it can be a great moderating element in the access to electronic commerce according to Landau (2012).

The objective of this article is to conduct an empirical study on the moderating effect of the socioeconomic conditions and educational level of electronic commerce adopters and their direct influence on the relationship between the facilitating conditions regarding the intention to use and use of e-commerce to verify whether, due to the incidence of the digital divide in poor and developing countries, electronic commerce presents barriers to access in its use and makes it more difficult for those citizens who belong to poor population groups with low educational levels to have the necessary conditions. As specific objectives, we want to check first whether, in the Colombian case, the facilitating conditions affect the intention and the electronic purchase; we then explore the moderating effect of the variables socioeconomic level and educational level of the sample on the previous relationship and verify that access to e-commerce in this country is being affected by a gap related to the socioeconomic and educational level of the population.

2Theoretical background and hypotheses2.1Technology acceptance modelSince the early 1970s, numerous models have been proposed to understand and explain the factors that determine the acceptance of information technologies. Some of them examine the relationship between the attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs of technology users and the level of use of the technology itself (Bonera, 2011). They include the following.

The theory of reasoned action (TRA) has been used to model consumer behaviour to assess the attitudes and beliefs of consumers; that is, it accounts for almost all types of human behaviour based on the beliefs and intentions of individuals (Bonera, 2011; O’Cass & Fenech, 2003). The TRA proposes that an individual's behaviour is determined by his or her intention to behave in a certain way and that this intention is influenced by attitudes and subjective norms. Although most of the support for the theory has come from the literature on social psychology, the TRA has been used successfully to identify key elements of consumer decision-making and in several marketing fields. Therefore, various researchers have refined the TRA to improve its predictive character; two of these versions are the technology acceptance model (TAM) and the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) (Keen, Wetzels, de Ruyter, & Feinberg, 2004).

The technology acceptance model (TAM) is an instrument that emerged to estimate and predict how users accepted the emerging information technologies (ITs) that had gained popularity in the early 1980s. It was used to assess the potential market for a variety of new applications in the multimedia field and for image processing as well as to target investment in development activities (Peinado, Salas, & Campos, 2011). The TAM uses the TRA as its theoretical basis for specifying the causal links between the perceived usefulness of consumers, the perceived ease of use, the attitude towards use, and the actual use of technology in particular (Davis, 1993; O’Cass & Fenech, 2003). That is, the model suggests that these variables are good indicators of the attitude and intention of potential users when choosing to use (or not to use) technology based on initial perceptions (Bonera, 2011).

The TPB is an extension of the TRA in which the perceived control variable is incorporated as an antecedent of the intention/effective behaviour to observe the degree of control that the individual has over his or her behaviour. The variables in the TPB are attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived control (Agudo-Peregrina, 2014). The TPB is one of the approaches that has most commonly been used to explain different purchasing decisions, because it has established the conceptual basis of much of the research focused on the study of consumer behaviour (Sanz Blas, Ruiz Mafé, & Pérez Pérez, 2013).

From the TPB, Taylor and Todd (1995) developed the decomposed TPB (DTPB). This model aims to explain the behaviour of users based on the relationship between beliefs, attitudes, intention, and behaviour. According to this model, attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control are the elements that help researchers to understand the reasons or factors that explain individual actions, although the intention is regarded as the best indicator of behaviour (Sahli & Legohérel, 2014).

The model of personal computer utilization (MPCU), developed by Thompson, Higgins, and Howell (1991), seeks to predict behaviour in the use of PCs (personal computers) based on Triandis (1971) theory of interpersonal behaviour (TIB), which argues that behaviour is determined by attitudes (what people would like to do), social norms (what they think they should do), habits (what they have typically done), and the expected consequences of their behaviour.

Thompson et al. (1991) redefined the Triandis (1980) model and suggested that people's behaviour in relation to the use of technology can be predicted by a combination of intended use based on attitudes, norms, and past behaviours. The MPCU takes into account how an individual uses the PC, what motivates him or her to use it, the social norms that establish the use of technology in the workplace, the habits of the person in relation to the PC, the benefits expected from the management of the computer, and the enabling conditions that make it possible to access it (Fernández Morales, Vallejo Casarín, & McAnally Salas, 2015).

The diffusion of innovations theory (DIT) was developed by Rogers (1995) and has been used to study a variety of innovations. It identifies five attributes of innovation that influence adoption and acceptance behaviour: relative advantage, complexity, compatibility, trialability, and observability. Subsequent to the empirical research of Rogers (1995), a model of the proportions of adoption of the members of a social system was obtained; these are predictable, regardless of the type of technology disseminated: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and dawdlers (Sánchez-Torres & Arroyo-Cañada, 2016).

The theory of diffusion of innovation establishes a set of principles by which a general innovation is disseminated in a society, the term diffusion as the process by which an innovation is communicated through channels on a period is used time all members of a society, being the key to the great social changes in humanity (Rogers, 1995).

According to Rogers (1995), the innovative approach called “innovativeness” is the degree to which an individual has come forward to adopt new ideas than other members of the social system, categorizing therefore adopt the attitude of these innovations: (1) innovative, (2) initial early adopters, (3) majority (4) late majority and (5) behind. Also, the degree of participation of these categories in the use of innovation, the diffusion in society, have different characteristics, being predominantly highly educated, high social status and a high degree of social interaction in users early stages of this innovation (Table 1).

Process diffusion of innovation.

| Time phases | Influential adopters | Prevailing socioeconomic characteristics according to Rogers (1995) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Launch of innovation: A new technology is created (patents, scientific, etc.). | Innovative: They are the ones who first tested the innovation, they are adventurous, do not take into account the established social order and therefore tend to break proposing innovation. | • They have high levels of education • Belong to a higher social status • Have a lot of social interaction • Innovative orientation |

| 2. Adoption experts: Usually this patent is manufactured or distributed to high prices and difficult to acquire. | Early adopters: They are more integrated with the social system, the cosmopolitan attitude allows them to have social influence, and they therefore have respect from other members of society. | |

| 3. Initial popular adoption: It is manufactured or distributed volumetrically and is freely accessible. | Early majority: They are very important because they are the passage of minorities to the social majority, usually slow to adopt innovation. | • High levels of social influence |

| 4. Overcrowding: It is offered at all levels of the population, has a relatively low access cost. | Late majority: Are those who adopt the innovation once they see it introduced in society, are a benefit or usefulness proven in other members and adopted. | • Little social influence • High levels of utilitarianism (expectations of effort/perceived usefulness) |

| 5. Technology masses: Technology is commonly used and can be readily replaced by novel substitutes. | Laggards: They are almost the entire population using innovation and are the last group to adopt the innovation (their traditions are not kept and are influenced by others). |

While the end of mass states, you will find that in general the users have mastered and have become common such innovation by presenting a group of “laggards” that in the case of e-commerce found a study that actually shows that there are people whose characteristics do not allow them to adopt the use of the internet for shopping, either by age or by learning to use, it took over in using this virtual channel to the other users (Mattila, Karjaluoto, & Pento, 2003).

According to Rogers (1995), the adoption of a technological innovation of an individual depends on the type of social system to which it belongs, being influential factors Standards and influence leader, extrinsic factors that patterns of technology adoption or call Social Influence Subjective Norm (Venkatesh et al., 2003); moreover, according to the theory proposed by Bandura (1977) learning is generated by each individual, by observing the behaviour of other members create similar behaviour called vicarious experience, which influences him to adopt or not innovation.

The social cognitive theory (SCT) assumes that individual behaviour is not only an imitation of observed behaviour but also perfected by the individual according to the experiences and results achieved. In this manner an individual's cognitive skills influence the behaviour of the use of technology, and the individual's successful experiences with technology also influence his or her cognitive perception (Agudo-Peregrina, 2014). The highlight of this theory in studies of technological appropriation is the introduction of the concept of self-efficacy, which refers to the perception that a person has about his or her ability to perform a task successfully (Fernández Morales et al., 2015). For the SCT all behaviour is defined by the interaction between the following elements: the personal factors that characterize an individual, his or her behaviour, and the environment (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

This contribution was the basis for Venkatesh et al. (2003) proposal in the unified theory of technological adoption (UTAUT) that the facilitating conditions directly influence the adoption behaviour of a technology, defending itself as the degree to which an individual believes that the organizational and technical conditions to support the use of a system exist. This model focuses on the study of the adoption of electronic commerce, being the reference for analysing all uses of the virtual platform, electronic banking, social media, electronic B2C–C2C–B2B commerce and online government, among others. For the case of the facilitating conditions, the literature contains great contributions regarding its direct influence on the intention to use and on the use of electronic purchasing.

According to the contributions of these studies, the following hypotheses are proposed (Fig. 1):H1

The facilitating conditions positively affect the intention to buy online.

H2The facilitating conditions positively affect the use of Internet purchasing.

2.2Moderating factors of the facilitating conditions and their effect on electronic purchasingThe models of the adoption of electronic purchasing have verified that there are moderating variables that increase or reduce the latency of the relations between the previous variables and the intention to use and use of e-commerce, factors such as gender, age, and obligatory use of equipment (Fernández Morales et al., 2015); however, the purchase of new products and the use of new products (Fernández Morales et al., 2015; Venkatesh, Thong James, & Xu, 2012) may also be affected by other factors, such as the socioeconomic level and educational level (Agudo-Peregrina, 2014), especially in countries where the digital divide is latent (Landau, 2012).

The socio-economic level determines the purchasing power of buyers; its importance lies in the fact that it has traditionally been estimated that innovations break into society through high socio-economic subjects (Rogers, 1995), although this may not be correct (Agudo-Peregrina, 2014; Van Dijk & Hacker, 2003). In this paper we present the results of a study of the e-commerce model.

The educational level is another traditional marketing variable, like the socioeconomic level. Studies on the adoption of electronic purchasing (Chen & Dhillon, 2003; Garin-Muñoz & Perez-Amaral, 2011; Hui, Wan, & Ho, 2007) have shown higher numbers of buyers with high levels of education (Allred, Smith, & Swinyard, 2006; Bellman, Lohse, & Johnson, 1999; Porter & Donthu, 2006; Siyal, Chowdhry, & Rajput, 2006; Soopramanien & Robertson, 2007). In this approach other have authors noted that, with a higher level of education, more information is available on buying over the Internet and therefore this may affect variables such as the facilitating conditions and their relationship with electronic purchasing (Sánchez-Torres & Arroyo-Cañada, 2016).

From the above the following hypotheses are proposed (Fig. 1):H3

The socioeconomic level generates a positive moderating effect on the relation between the facilitating conditions and the intention to purchase on the Internet.

H4The socioeconomic level generates a positive moderating effect on the relationship between the facilitating conditions and the use of the Internet for purchasing.

H5The level of education generates a positive moderating effect on the relationship between the facilitating conditions and the intention to buy online.

H6The level of education generates a positive moderating effect on the relationship between the facilitating conditions and the intention to buy online.

3MethodologyFirst this section describes how the measurement tool was constructed and how the information was collected, then it analyses the model and tests the hypotheses proposed.

3.1Measurement toolTo contrast the hypotheses of the proposed model, items extracted from the literature were used, and, to avoid problems of translation into Spanish, the adapted measurement scale was taken from the study on the general adoption of electronic commerce in Spain (Agudo-Peregrina, 2014). Likewise, a pre-test with a total of 20 people was developed to eliminate items that involved problems.

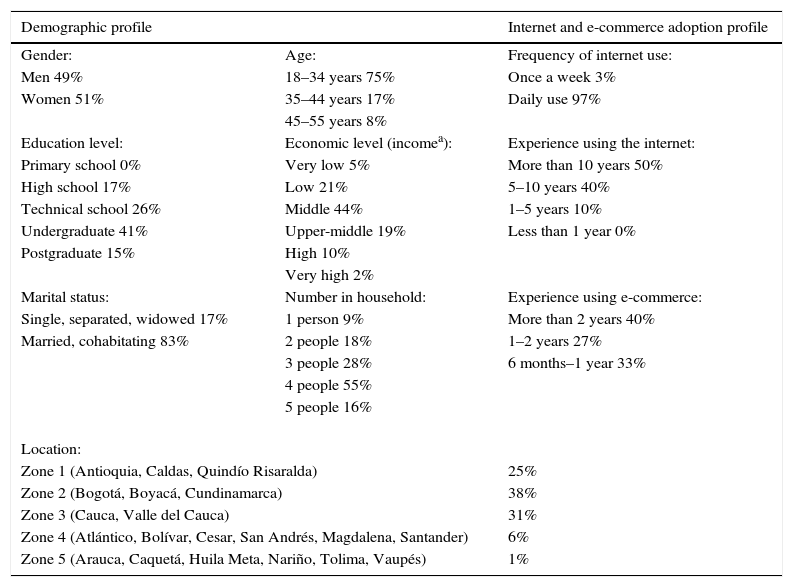

3.2Sample and collection of dataThe sample consisted of people who use the Internet for purchasing in Colombia, the sample was determined using the methodology of stratified sampling with geographic quotas, as this is deemed the most appropriate for studies of large populations that require a representative sample of all members (Hoe, 2008).

For data collection mechanism, using an electronic questionnaire that had been validated in other studies for this type of research (Escobar-Rodríguez & Carvajal-Trujillo, 2014). To facilitate the answers, the multi-item methodology was followed by constructs using Likert-type scales for the questionnaire responses, ranging from 1 (=“I strongly disagree”) to 7 (=“I strongly agree”), as well as measuring effectively variables that are not directly observable (Churchill & Iacobucci, 2005).

The data collection was carried out during the months of November 2015–May 2016. To achieve the objectives of the fieldwork, a national team was formed with coordinators in each of the central cities to manage the research. The questionnaire was also disseminated and an incentive was offered among those who volunteered to respond to the survey: a laptop computer that was given to the winner of a draw held among all the participants in June 2015 in the city of Bogotá under the audit of the Gran Colombiano Polytechnic University Institution. A total of 1245 questionnaires were collected, of which 309 presented consistency problems in the answers, leaving a final sample of 936 valid questionnaires (Table 2).

Sample characteristics.

| Demographic profile | Internet and e-commerce adoption profile | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender: | Age: | Frequency of internet use: |

| Men 49% | 18–34 years 75% | Once a week 3% |

| Women 51% | 35–44 years 17% | Daily use 97% |

| 45–55 years 8% | ||

| Education level: | Economic level (incomea): | Experience using the internet: |

| Primary school 0% | Very low 5% | More than 10 years 50% |

| High school 17% | Low 21% | 5–10 years 40% |

| Technical school 26% | Middle 44% | 1–5 years 10% |

| Undergraduate 41% | Upper-middle 19% | Less than 1 year 0% |

| Postgraduate 15% | High 10% | |

| Very high 2% | ||

| Marital status: | Number in household: | Experience using e-commerce: |

| Single, separated, widowed 17% | 1 person 9% | More than 2 years 40% |

| Married, cohabitating 83% | 2 people 18% | 1–2 years 27% |

| 3 people 28% | 6 months–1 year 33% | |

| 4 people 55% | ||

| 5 people 16% | ||

| Location: | ||

| Zone 1 (Antioquia, Caldas, Quindío Risaralda) | 25% | |

| Zone 2 (Bogotá, Boyacá, Cundinamarca) | 38% | |

| Zone 3 (Cauca, Valle del Cauca) | 31% | |

| Zone 4 (Atlántico, Bolívar, Cesar, San Andrés, Magdalena, Santander) | 6% | |

| Zone 5 (Arauca, Caquetá, Huila Meta, Nariño, Tolima, Vaupés) | 1% | |

The latent variable regression analysis method used in this study was performed with the Smart-plus 3.0 PLS programme, based on the technique of partial least squares (PLS) optimization, which is a multivariate technique to test structural models and is recommended for exploratory models; it has been used on other occasions to test the UTAUT model due to the large number of latent variables that it contains (Escobar-Rodríguez & Carvajal-Trujillo, 2014; Kiwanuka, 2015; Matute Vallejo, Redondo, & Acerete, 2015). The analysis of the data was performed in two stages: the first estimated the measurement model and the second examined the validity of the structural model.

4.1Validation of the measurement modelThe validation process of the measurement instrument was based on exploratory analysis. The first step was to establish the convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs and the reliability of each item. The convergent validity of each construct was acceptable, since they all had loads greater than 0.505 (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2014). The individual reliability of each item was measured by the correlations of the loads of each item versus each variable, as shown in Table 3. It can be verified that the loads for each indicator were significant, so they were all validated. To measure the internal consistency of all the indicators in relation to their corresponding variables, the study used the Dillon–Goldstein test, known as the composite reliability coefficient, for which all values were greater than the acceptable minimum of 0.70 (Gefen, Straub, & Boudreau, 2000). The Cronbach's alpha test was also applied, also obtaining values above the minimum value allowed for confirmatory studies (Churchill & Iacobucci, 2005). Finally, the convergent validity was again analyzed taking into account the variance; that is, there was a similar variance between the indicators and their construct, which should be greater than 0.50 of the variability explained by the indicators (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) (Table 4). The discriminant validity was verified by comparing the AVE value of each variable with the correlation of each construct of each variable squared, since the values obtained from the square root of the AVE were higher than the values of the constructs; therefore, it can be considered that each variable is related more strongly to its own items than to those of other variables (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) (Table 5).

Indicator weights.

| Indicator | Weight | t-valuea |

|---|---|---|

| PI1 | 0.857 | 41.757 |

| PI2 | 0.883 | 42.619 |

| PI3 | 0.853 | 40.061 |

| FC1 | 0.891 | 42.257 |

| FC2 | 0.920 | 46.245 |

| FC3 | 0.853 | 33.819 |

Following the structural model, resampling was performed using the bootstrapping technique, with 1000 sub-samples from the study data, and a significance test of the model parameters was performed. All of the above showed that the model fulfilled its predictive capacity by obtaining R squares greater than 0.10 (Hair et al., 2014). The hypotheses were tested as follows: hypothesis 1 was successfully validated (H1: B=0.656), which shows that the facilitating conditions have a direct and positive influence on the electronic purchase intention; hypothesis 2 was equally significant (H2, B=0.237), since the facilitating conditions have a direct and positive impact on the use of electronic purchasing. These two results were expected considering that the literature has shown that facilitating conditions are one of the main influential variables in electronic purchasing (Agudo-Peregrina, 2014; Escobar-Rodríguez & Carvajal-Trujillo, 2014; Venkatesh et al., 2012; Yee-Loong Chong, Ooi, Lin, & Tan, 2010). Hypothesis 3 was also validated (H3: B=0.045), giving significance to the moderating effect of the socioeconomic level on the incidence of the facilitating conditions in the electronic purchase intention; likewise, hypothesis 4 was significant (H4: B=0.025), also showing a positive influence on the effect of the facilitating conditions on the use of electronic purchasing. In relation to the level of education and its moderating effect on the incidence of the facilitating conditions on the electronic purchase intention, hypothesis 5 (H5: B=0.073) is valid, equally having a direct and positive effect on the facilitating conditions and its relation to the use of electronic commerce in hypothesis 6 (H6: B=0.020) (Table 6 and Fig. 2).

Summary of the structural validity of the model.

| Effect | Original sample (O) | R squared | Standard deviation (STDEV) | t Statistics (IO/STDEV) | p values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention to purchase→electronic purchase | 0.213** | Purchase use: R=0.175 Intention to purchase: R=0.426 | 0.043 | 4.945 | 0.000 |

| Economic level→facilitating conditions – intention to purchase | 0.045* | 0.026 | 1.741 | 0.082 | |

| Education level→facilitating conditions – purchase | 0.020* | 0.041 | 2.487 | 0.026 | |

| Education level→facilitating conditions – intention to purchase | 0.073* | 0.028 | 2.657 | 0.008 | |

| Facilitating conditions→electronic purchase | 0.237* | 0.047 | 2.797 | 0.025 | |

| Facilitating conditions→intention to purchase | 0.656** | 0.022 | 30.105 | 0.000 | |

| Economic level→facilitating conditions – purchase | 0.025* | 0.035 | 1.919 | 0.043 | |

| Economic level→purchase | 0.093* | 0.033 | 2.774 | 0.006 | |

| Economic level→intention to purchase | 0.022* | 0.025 | 2.083 | 0.034 | |

| Education level→purchase | 0.045* | 0.031 | 1.825 | 0.054 | |

| Education level→intention to purchase | 0.055* | 0.025 | 1.994 | 0.046 |

It is apparent that the facilitating conditions are a fundamental factor in the adoption of electronic commerce but that this relationship may be moderated by the socioeconomic level and the level of education of its adopters in a country like Colombia, so those who belong to socially high and/or higher university levels will tend to have the necessary enabling conditions for the use of electronic commerce. The results have been shown to be satisfactory in the face of all the proposed hypotheses. Therefore, this study proposes in an exploratory way first of all that for Colombia the necessary conditions for electronic purchasing are positive precedents of the use of electronic commerce; thus, users of this commercial channel consider that they have the physical and technical ability and knowledge necessary to carry out these transactions, that is, they have computer equipment (PCs, laptops, smartphones, tablets), the necessary means of payment (credit and debit cards, Internet banking, other virtual currencies like Paypal, etc.). Second, it has been validated in an exploratory way for this country that the socioeconomic level and the level of education influence the presence of these conditions, reinforcing the idea that the particular sample presents a large segment of people of high socioeconomic levels and a high level of education and that the adoption of e-commerce in Colombia is accentuated for this population group, so the situation that Landau (2012) affirmed about the digital divide existing in development, that people with fewer resources and fewer studies may not have the necessary enabling conditions to use e-commerce, may apply.

6ConclusionsThe main contribution of this study is the exploratory validation of the moderating effects of the socioeconomic level and the level of education in the adoption of electronic commerce, especially in relation to the incidence of the facilitating conditions that precede the intention to use and the use of electronic commerce. These results provide empirical evidence in the study of the adoption of electronic commerce in the case of countries with high levels of social inequality and consequently a digital divide, which may lead to the development of electronic commerce being unequal within these societies. This can generate the conditions for the diffusion of innovation at the initial level, as described by Rogers (1995), in which the social group belonging to high socioeconomic strata or a high educational level can access new technology more easily, so the adoption of electronic commerce in this type of country may be at a lower level than in other developed countries (Sánchez-Torres & Arroyo-Cañada, 2016).

At the corporate and governmental level, the results show that e-commerce in Colombia presents the necessary conditions for its use for its current adopters, taking into account that it is being adopted to a greater extent by people with high purchasing power and superior education, a fact that can be used by companies that trade on the Internet to offer products and services that focus on these segments. For governments the goal is to reduce the digital divide and its effect on the access of all socio-economic segments to electronic commerce to make this moderating effect ineffective. Finally, it is proposed as a future research line to test whether these demographic variables exert this moderating effect in other countries with similar characteristics and to perform a cross-country study with a developed country to test these results.