The study of differences in cultural dimensions across cultures seeks to identify a set of characteristics (beliefs and values) that are common to certain groups and individuals that are united in feeling, thought, and action. The aim is to find patterns, profiles, and behavioral standards that demonstrate different cultural behaviors and that may help explain differences in people's behavior and attitudes to innovate, as well as the differences in performance of the territories. Thus, the aim of this study is to identify and analyze cultural standards in two towns in Portugal, Covilhã and Guarda, through the cultural dimensions developed by Hofstede. These cultural standards can help to explain the different dynamics of regional innovation. In this sense, we made up a case study using the survey developed by Hofstede. Then, we applied the questionnaire developed by Hofstede and concluded that what prevails in both cities is a reduced power distance, high individualism, femininity, high uncertainty avoidance, and short-term orientation.

1. Introduction

The term "culture" has many meanings, deriving from the Latin and referring to the tillage of the ground. In Western languages "culture" is equivalent to "civilization" or "refinement of the mind." Culture is a collective phenomenon since it is shared by people living in the same social environment.

The influence of values and cultures is seen increasingly as crucial in all areas of human life, as evidenced by the studies in all fields of science related to life in society, social behavior, consumer, personal, career, life expectancies (Santos & Reis, 2005), etc., or in personal relationships or between societies and countries. Indeed, the studies that examined conflicts between countries and that equate cultural assumptions (Rawwas et al., 1998) show that a company's strategy must consider cultural diversity to ensure efficiency (Hofstede, 1980). Other studies address behavior of consumers, the influence of some social groups in these decisions (Zhang & Gelb, 1996) and the intended communication by companies (Aaker, 2000). Even the form of society's organization is necessary to think that the evolutionary path depends on the cultural features that characterize a society (Gannon, 1994).

All learning throughout life will influence the behavior of individuals-behavior that causes these different cultural patterns, which are the result of continuous learning and which find their origin in many social environments encountered during life. Culture explains and allows understanding the behaviors of individuals and the type of development reached by each country. The patterns of national, regional, or local culture level may influence the relations, the establishment of networks of innovation and cooperation, as well as an innovation system and therefore the capacity for innovation and competitive performance, whether of companies, regions, or countries. However, within a nation, there are also cultural differences associated to regions with different social environments and even weather that translate into cultural differences (Hofstede, 1980). Thus, with regard to cultural differences between countries and regions, these can be illustrated and measured through the dimensions of culture or cultural standards.

Given these assumptions, the objective of this paper is to identify and analyze patterns of cultural behavior in terms of two territories of Portugal, through the cultural dimensions developed by Hofstede (1991), which may serve to explain the different territorial dynamics of innovation and development and to help (more later) to formulate development policies that suit the specificities of these territories. In fact the innovation may be different in different cultural contexts, and can verify a clear link between culture and innovation, as can be seen in the reports of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor1 (GEM), which support the analysis of countries as more or less enterprising/innovative. In this sense, we applied the study/questionnaire developed by Hofstede in 1994 to the cities of Guarda and Covilhã in January 2010.

This paper is structured in five points. After the introduction, there is a brief literature review. Part two discusses the concepts of culture, cultures, and cultural dimensions, and part three makes the connection between cultural patterns and innovation, seeking to enhance the ones that stimulate innovation in opposition to the attitudes that inhibit innovation. Part four includes the empirical study, presenting the methodology used and the main results. Finally, part five discusses conclusions, implications, and limitations, and suggests clues for future research.

2. Literature review: Culture, cultures and cultural dimensions — Hofstede model

For the anthropologist Tylor (1920, p. 1), culture (or civilization) "is the complex whole, which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habitats acquired by man as a member of society." In a broad sense, it can be understood as the set of values that determine the being, the feeling, and the acting, and agglutinates common ways of reaction to events by a group of individuals.

For Triandis (1995), culture usually is linked to a language, a particular time, and a place, and emerges in interaction: "As people interact, some of their ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving are transmitted to each other and become automatic ways of reacting to specific situations. The shared beliefs, attitudes, norms, roles, and behaviors are aspects of culture" (Triandis, 1995, p. 4).

According to Hofstede (1991), culture can be understood as a set of patterns, thoughts, and emotions, called "mental programs," that are shared and can be described and compared. These programs vary from individual to individual, but also have elements common to a group, which are shared and collective. It can be understood as a complex system of rules for groups, organizations, and societies (Thomas, 1988). Members of a culture share these rules they learned in the socialization process (Brück & Kainzbauer, 2002).

The study of culture, cultural differences, and intercultural interactions has as its aim, among other things, the understanding of the international organizational dynamics, sensing, interpreting and managing behavioral differences by members of different national cultures in the context of management and its business (Fink et al., 2005). Also Hofstede (1991) tried to analyze the different national cultures, reflected in the respective organizational structures, through attitudes and values related with the work in a multinational company in different countries and regions.

According to Hofstede (1991), the study of culture reveals that human groups think, feel, and act differently, but there are no scientific parameters that allow a group to be considered superior or inferior to another. Culture is the result of interaction among individuals, which is simultaneously one of the components that determine it (Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, 1998).

Culture is something collective, related to beliefs and values shared by members of a particular group, and simultaneously is something distinctive of these individuals' faces to different groups, presenting a set of common characteristics that allow them to identify themselves as belonging to this group, join in the feeling, in the thought and action, and who are called Cultural dimensions or Cultural Standards (Rebelo et al., 2009).

Cultural differences between countries and regions may well be illustrated and measured through the dimensions of culture (Hall & Hall, 1990; Hofstede, 1980, 1987, 2001; House et al., 2004; Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck, 1961; Rokeach, 1973; Schwartz, 1992; Trompenaars, 1993; Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, 1998).

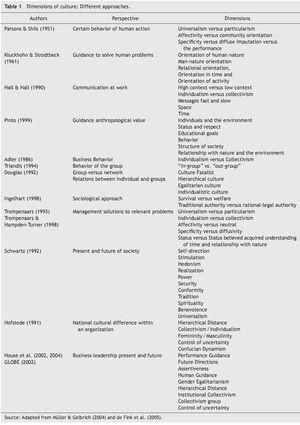

The cultural dimensions intended to measure cultural differences and based on a factor analysis' formalized attempt to measure cultural specifications. The approaches that study the differences of cultures through the cultural dimensions reflect diverse perspectives and viewpoints. Some focus on the guidelines of the values (Parsons & Shils, 1951; Strodtbecks & Kluckhohn, 1961; Hall & Hall, 1990; Pinto, 1999), others on the relationship (Douglas, 1992), others analyze the group behavior (Adler, 1986; Triandis, 1995), others deal in terms of sociological orientations (Ingelhart, 1998), of management (Trompenaars, 1993; Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, 1998; Hofstede, 1991) and future orientations of society (Schwartz, 1992; House et al., 2002, 2004). In several studies on cultural differences, it is possible to find that the authors identified different dimensions to distinguish and classify the cultures (Table 1), and characterized and reflected the different perspectives of each approach.

The study of the differences of cultures through cultural dimensions seeks to recognize/identify a set of characteristics (beliefs and values) common to certain groups of individuals united in feeling, in thought, and in action. It aims to find patterns, profiles, and behavioral standards that demonstrate different cultural behaviors. These patterns may help explain differences in behavior and attitudes of people more or less innovative, and explain differences in performance and development of territories as well.

It should be noted that cultural standards are based on approaches applied to identify relevant characteristics of the rules for cross-cultural interactions. The concept is directly related to the interactive patterns (Brück & Kainzbauer, 2002). Cultural standards combine all forms of perception, thinking, judging, and behavior that people share in a common cultural environment that assesses how normal, self-evident, typical, and obligatory they are. Thus, the cultural patterns determine how we interpret our own behavior and the behavior of others. They are considered "basic" if applied to a variety of situations and determine the majority of perceptions, thoughts, judgments, and behaviors of a group. Moreover, they are highly significant for perceiving-judging-mechanisms of behavior among individuals (Thomas, 1993).

An interesting aspect of these cultural patterns is that human actions can determine contact with people with a different culture. Moreover, the method of cultural patterns illustrates how differences in the types of perception, forms of feeling, thinking, judging, and acting are reflected in intercultural incidents or clashes (Thomas, 1996; Meierewert & Fink, 2001; Fink et al., 2005). However, it is extremely difficult to identify cultural patterns, since one cannot analyze them directly because they automatically influence our perceptions, judgments, and behaviors (Brück & Kainzbauer, 2000).

In the context of management, the measurement of national culture has triggered a renewed interest in transnational research (Gouveia et al., 2003; Bond, 2002; Bearden et al., 2006). This interest is the result of growing concern to analyze the influence of national culture on macro-level phenomena, such as access and entry into foreign markets (Makino & Neupert, 2000), in the definition of global brand strategies (Raman, 2003), in the way managers take decisions outdoors (Tse et al., 1988), and in market orientation of the company (Selnes et al., 1997). Moreover, the values of national culture have been shown to influence the micro level, such as on consumer behavior in specific international markets (Aaker & Williams, 1998), on the capabilities of advertising in several countries (Albers-Miller & Gelb, 1996) and on individual perceptions of the effect of country of origin (Gürhan-Canli & Maheswaran, 2000).

Although the concept of culture was originally conceptualized at an aggregated level, the national level, Schwartz & Ros (1995) and Blodgett et al. (2008) emphasize that the concept of culture can be applied to other more disaggregated levels of analysis, and that the national level may conceal important variations, including the regional (Laroche et al., 2005). At the level of organization, it is possible to find diverse cultures, including the specific socio-professional categories (Bilhim, 2006). Thus, as people have different cultures, so do the regions within a nation and the organizations and their departments. So, as the cultures of societies help to influence the behavior of their members, the culture of the regions also influences the behavior of its actors that is territorially relevant, and the culture of organizations influences opinion and behavior of their employees.

To identify cultural differences among individuals, several studies have used the work of Hofstede (1991) as a starting point (Bond, 2002), using the Values Survey Questionnaire 1994 (VSM 94) as an analytical tool (Bearden et al., 2006). It also noted other studies that dispute the scales used (Spector et al., 2001) and wonder how they built dimensions of national culture (Gouveia et al., 2003). Blodgett et al. (2008), for example, sought to test the validity of Hofstede's methodology, arguing that the issue is important for understanding consumer behavior in different cultural contexts: nationalities, religions, regions, and countries, concluding that it lacks validation when applied to an individual level of analysis. However, we cannot fail to recognize the essential and pioneer contributions of Hofstede in intercultural studies and in the conceptualization of national culture, so we will present some of its main conclusions.

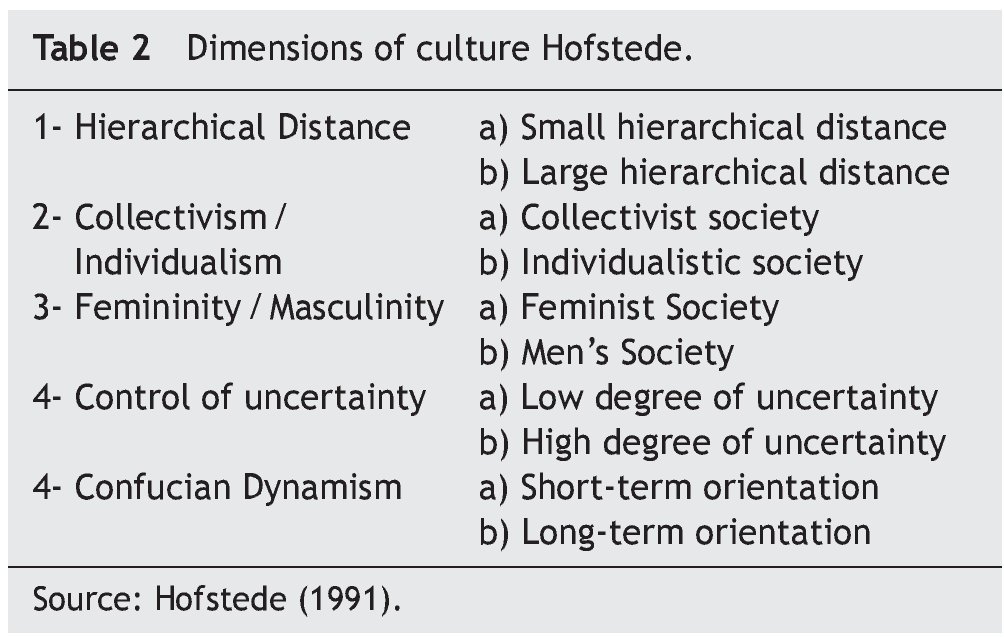

The dimensions of the different national cultures studied by Hofstede (1991) have the influence of Inkeles & Levinson (1954) and try to group the fundamental problems of humanity, which had repercussions on the functioning of societies, of groups within societies, and on individuals within the groups, and have the following designations (see the Table 2).

For Hofstede (1991), the Hierarchical Distance can be defined as the measure of the degree of acceptance by those who have less power in institutions and organizations of a country. An asymmetric and unequal distribution of power is thus a factor that shows the relationship of dependency. In countries where the hierarchical distance is lower, the dependence of subordinates on the leadership is limited, and there is more interdependence and consultative style.

As the degree of individualism or collectivism, Hofstede (1991) defined this dimension by taking into account each of the concepts. Individualism characterizes societies in which ties between individuals are not very strong, each one should take care of him/herself, and the closest family members. Collectivism, by contrast, characterizes societies in which people are integrated from birth into strong, cohesive groups that protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty.

The degree of Masculinity or Femininity meets together in a single factor, a number of issues that were systematically answered differently by men and women. Thus, Hofstede (1991), designated that in male societies where the roles are clearly differentiated, the man must be strong to impose himself and become interested in material success, while the woman should be more modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life. Feminists prefer societies in which social gender roles overlap, both men and women should be modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life.

Control of Uncertainty measures the degree of concern of individuals against the unknown or uncertain situations. This sentiment is expressed, among other forms, by stress and need for predictability: a need for written rules or not. This factor includes the tendency of individuals to think that what is different is dangerous.

For the Confucian Dynamism2 Hofstede (1991) considers that this dimension is associated with the pursuit of truth, opposing a long-term orientation in life and facing a short-term orientation. This dimension was developed by Confucius, a thinker of Chinese origin who lived in China in 500 A.C., and tried to serve many local lords in divided China in this period. The teachings of Confucius consist of lessons in ethics without religious content. They are a set of practical guidelines for everyday life that Confucius drew from Chinese history.

3. Cultural patterns and innovation

According to Hofstede (1991), the standards come from the cultural heritage of each society, as well as mental functions and behaviors associated with them, through which the individuals of these societies express themselves and rely their existence. The Learning and the knowledge of those cultural patterns facilitate the integration of the individual in society, allowing him/her to act on it, to interact with others individuals, and predict the reactions and the behaviors of others (verbal and nonverbal symbols).

Innovation, in turn, concerns the search, discovery, experimentation, development, imitation, and adoption of new products, new production processes, and new organizational structuring (Dosi et al., 1988) and can be considered as a new use of possibilities and pre-existing components, reflecting previously existing knowledge but combined in new ways (Lundvall, 1992). Indeed, for Schumpeter (1934), innovation could reside in new products, new processes, new sources of raw materials or new market structures and thinking on innovation at the industry level (in reorganization) the creative entrepreneur and pioneer (heroic), who leads a process that would follow imitators and adapters, and that is now known as the phenomenon of entrepreneurship.

Thus, with regard to innovation and the level of entrepreneurship are favored by these cultures where dominated the low hierarchical distance, under control of uncertainty, high individualism and high masculinity (Tan, 2002; Zahra & George, 2002; Hayton et al., 2002; Silva et al., 2009). According to Hayton et al. (2002) and Silva et al. (2009) the control of uncertainty and high power distance inhibit innovation, while high individualism and masculinity stimulate it. Innovation is then shaped by cultural standards, norms, values, and ethics of a society. These influence the behavior of individuals and condition the more or less innovative contexts of companies and of territories.

Cultures that valorize and promote the need for self-realization, material gains, and autonomy, typical of individualistic societies, usually have the highest propensities to innovate and simultaneously the highest rates of business creation (Silva et al., 2009). Predominantly individualistic cultures are associated with high rates of business start-up because the valuation of work ethics and attitude prevailed for them to take risks (Hayton et al., 2002) and foment innovative contexts.

Also, companies with predominantly cultural characteristics associated with the masculine type promote competitiveness and the struggle for survival and, therefore, are positively associated with a higher level of entrepreneurship and innovation, while societies with predominantly female cultural characteristics seek to provide more opportunities to help mutual and social contacts and find consensus, acting more by intuition (Hofstede, 1994).

In turn, according to Hofstede (1994) the high hierarchical distance promotes centralization, bureaucracy, becoming an obstacle to creativity, innovation, and inhibiting entrepreneurship, while low hierarchical distance is associated with decentralization and interdependence, giving consultative style preference and thus promoting the creativity of the working groups and encouraging a major level of entrepreneurship.

Also, the high control uncertainty negatively affects innovation and the entrepreneurial initiative, favors the emergence of laws, formal and informal, over-restrictive formalism and principles. Such societies are characterized by high anxiety about the unknown, which creates uncertainty and risk. In contrast, societies with low control of uncertainty have a greater capacity to perceive, identify, and capture opportunities, which is crucial to generate a larger number of innovations and simultaneously raise rates of entrepreneurship (Hofstede, 1994).

Indeed, innovation involves a fundamental element of uncertainty related to the lack of ex ante technical and economic results (Dosi et al., 1988), because there is always a greater or lesser degree of uncertainty as to the results of the activities of Research and Development (R&D), and even to overcome the barriers of a technical nature, is to consider the uncertainty regarding market acceptance of innovation, not to suggest the possibility or opportunity to introduce innovation in the market.

Thus, the combination of high hierarchical distance with a high control rate of uncertainty is identified as a strong potentiator of instability and thus represents a significant inhibitor of entrepreneurial activity (Hofstede, 1994; Silva et al., 2009) and a serious obstacle to innovation, promotion of territorial and enterprise dynamics of innovation. What an organization were to do in the future is conditioned by what it was able to do in the past, that depends on its learning process and the nature of accumulated experience, as well as its culture.

Therefore, cultural patterns, norms, values, and ethics of a society influence the innovative behavior of actors in a region and can lead to different territorial dynamics of innovation, which may explain the different regional competitiveness. The behavior in the face of uncertainty, the attitude more or less proactive and innovative in the face of unknown situations territorially relevant actors in a region, may explain the past performance of the territories in terms of innovation and competitiveness, and simultaneously can reveal trends and enhance early behavior in the development of policies and instruments properly formatted and adapted to these territorial patterns.

Given the above, the aim is then to identify and analyze patterns in two cultural areas of the interior of Portugal that could eventually help in understanding differences in territorial dynamics of innovation and development.

4. Case study: Cultural patterns in the cities of Guarda and Covilhã

4.1. Methodology and sample

The regions chosen for the realization of this study were the cities of Guarda and Covilhã, two cities in the interior of Portugal. As part of this study, a survey was conducted for individuals in these regions, with the aim of identifying behavioral patterns of individuals of these two cities in terms of culture, in the perspective of Hofstede, which may serve in the future as an instrument to explain distinct dynamics of innovation and development of these territories.

The study of cultural patterns in Guarda and Covilhã fits into the type of empirical research (Yin, 1994) as defined as a process by which the data based on reality and harvested directly or indirectly, are used to generate knowledge, this requirement implies that these data are based on reality and not on preconceived judgments, or beliefs of the researcher. In this perspective, empirical research requires a high degree of objectivity, since the ideas presented are based on the evidence submitted the real world. It is a descriptive correlational research (Yin, 1994), as it has with its primary objective the description of the two samples, one representing the city of Guarda and another representing the city of Covilhã, phenomenon or establish relationships between variables.

In any study, the researcher chooses an instrument of data collection depending on the topic in question, of objectives, of the population or sample the intended audience, the time horizon and financial resources to the realization of research. Thus, we resorted to effecting the questionnaire as self-responsive, which allows us to gather information quickly and leave freedom of choice for respondents. To analyze and compare the cultures of the cities of Guarda and Covilhã through the cultural dimensions developed by Hofstede (1991), we used the international survey questionnaire developed by the author (Values Survey 1994 - VSM 94).

VSM 94 is a 26-item questionnaire developed to compare the cultural values of two or more persons, or one or more countries or regions. Their analysis is carried out according to the five dimensions of national or regional culture, mentioned above, based on four questions per dimension (hence it requires 5 × 4 = 20 questions). The remaining six are demographic issues in relation to the respondent's gender, age, education, type of employment, place of birth/residence, and nationality. The questionnaire was administered in accordance with the methodology defined by Hofstede3 and obtained the average distribution of matter in each of the cities studied.

The process of selecting a sample, the scope of any investigation, requires certain methodological steps that make it representative of the population, in order to allow generalization of results to the universe that was removed (Ferreira & Carmo, 2008). Although the purpose of generalization is, according to some authors, especially valued in psychological assessment of evidence, in this case we chose to follow the instructions for applying the Hofstede questionnaire.4

Thus, according to the instructions and recommendations of Hofstede,5 the minimum number of participants per country or region to be used in comparison is 20 comments. Below this number, the influence of a single individual becomes too strong. The ideal number is 50. Even better is to use more than one sample of respondents by country, as men and women, or those with higher, medium and low level of education. In this case, of course, the numbers 20 and 50 apply to each sample separately.

Based on the recommendations and assumptions defined by Hofstede,6 we chose in this study a sample of 50 individuals in each city under study. The questionnaire was administered randomly through telephone interviews, conducted the weekends during the month of January 2010. The sample is then simple random or probabilistic, according to Maroco (2010).

The process of data analysis involves several steps: coding responses, data tabulation, and statistical calculations. So, after collecting the questionnaires, we proceeded to the coding of each question per-si, releasing the results in a database and used the SPSS for data analysis. The presentation of results will be made by figures and tables, where they will be highlighted the most relevant data.

4.2. Results

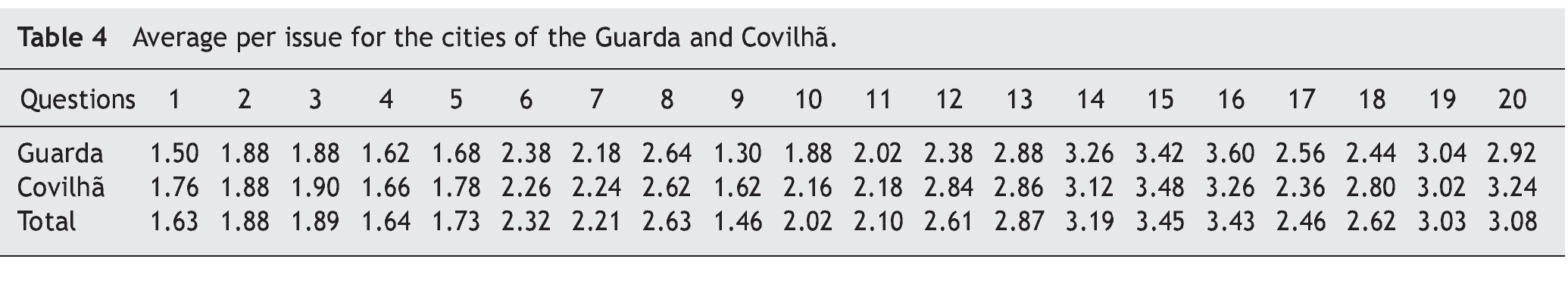

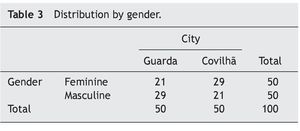

A brief analysis of the sample used in this study allows to draw the following general conclusions. With regard to gender, the sample comprised 100 individuals, 50 from the city of Guarda and 50 from the city of Covilhã, presenting a reverse distribution between the two cities as seen in Table 3. In Guarda, 29% of those respondents are male (corresponding to 29 men) and 21% are female (corresponding to 21 women). In contrast, in Covilhã, the sample consists of 29 females (29% of respondents to the survey) and 21 males (corresponding to 21% of the total sample).

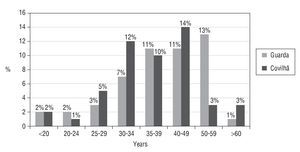

As for the age variable, the distribution is very similar between the two cities, as seen in Figure 1, and most of the sample of respondents is between 30 and 50 years.

Figure 1 Distribution of the variable age.

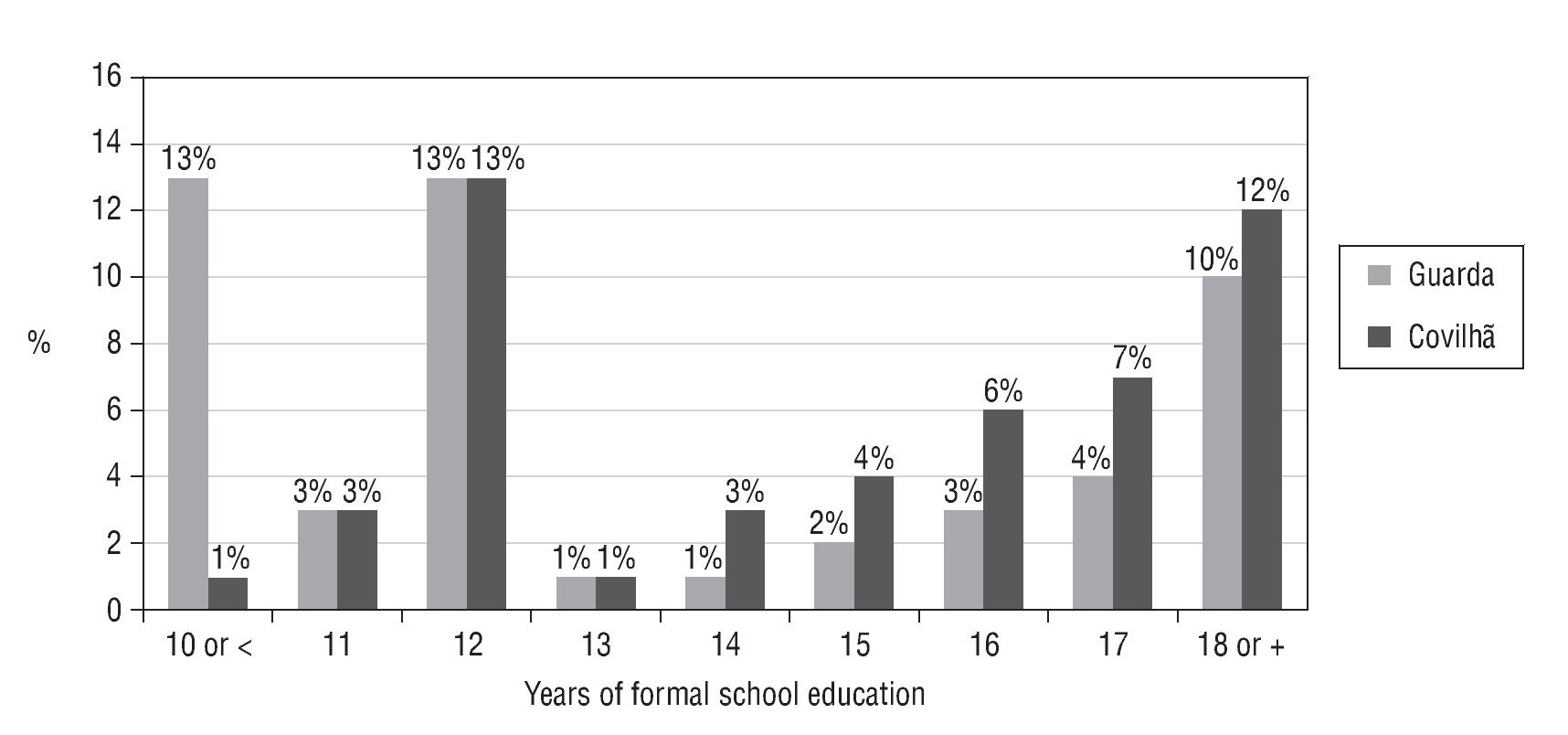

Regarding the education variable, the distribution is also very similar between the two cities, the most represented individuals have about 12 years of schooling and is more than 18 years of schooling. It should be noted that with less than 10 years of schooling stands Guarda, with the highest percentage of respondents (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Distribution of education variable.

The distribution of the sample concerning the variable occupation presents some differences between the two cities; it can be seen that 4% and 2% from the individuals of the cities of Guarda and Covilhã, respectively, have no occupation and 21% from Guarda and 17% from Covilhã work in services (work in general-office employee or secretary with general training) (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Distribution of the variable occupation.

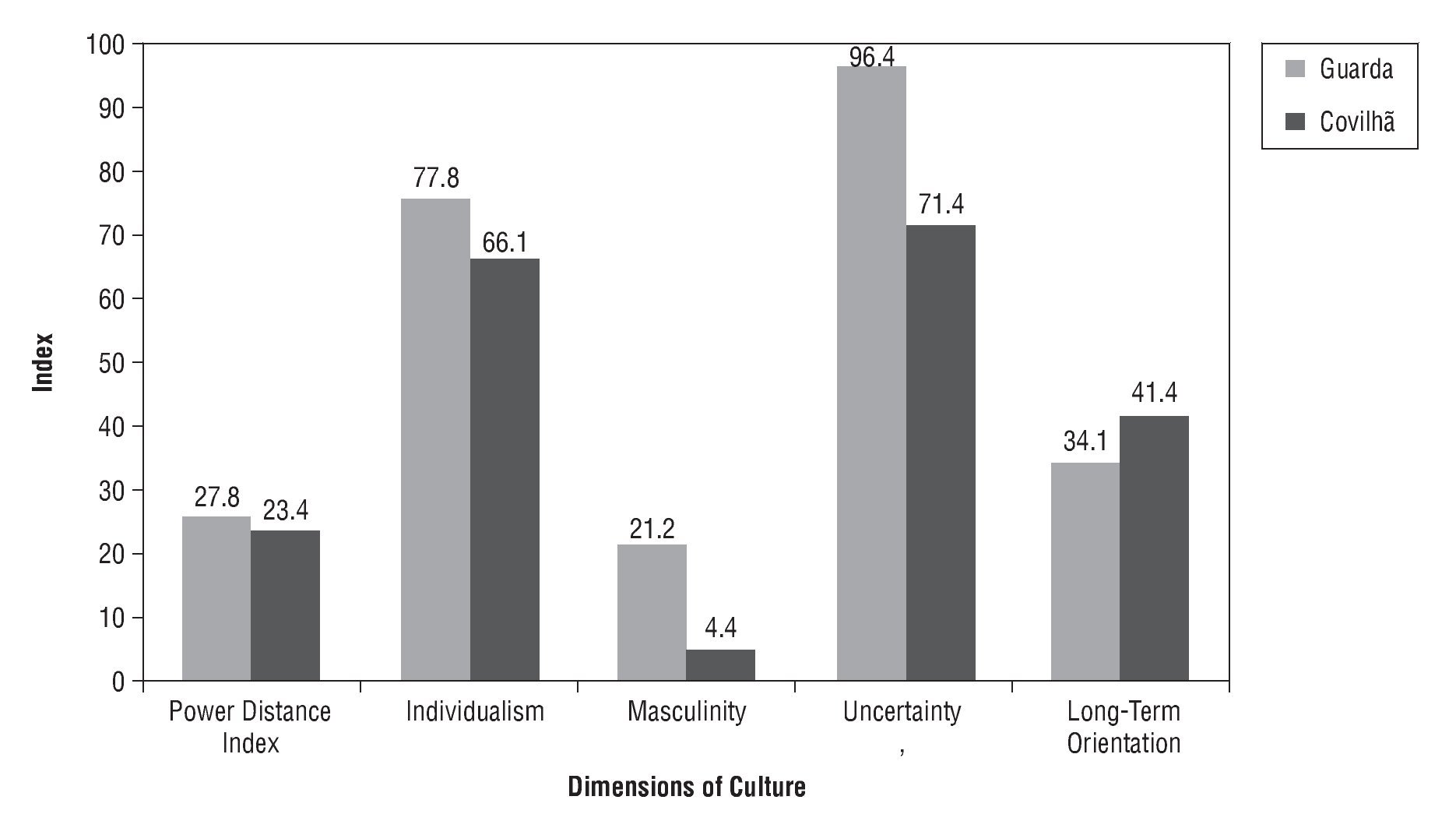

Applying the methodology mentioned above we obtained the average distribution per question in each city studied, as can be seen in Table 4 and allowed to determine the levels of power distance, individualism, masculinity, aversion/ uncertainty control and guidance for long term and thus find the five dimensions developed by Hofstede (1991) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Values calculated according to Hofstede's dimensions.

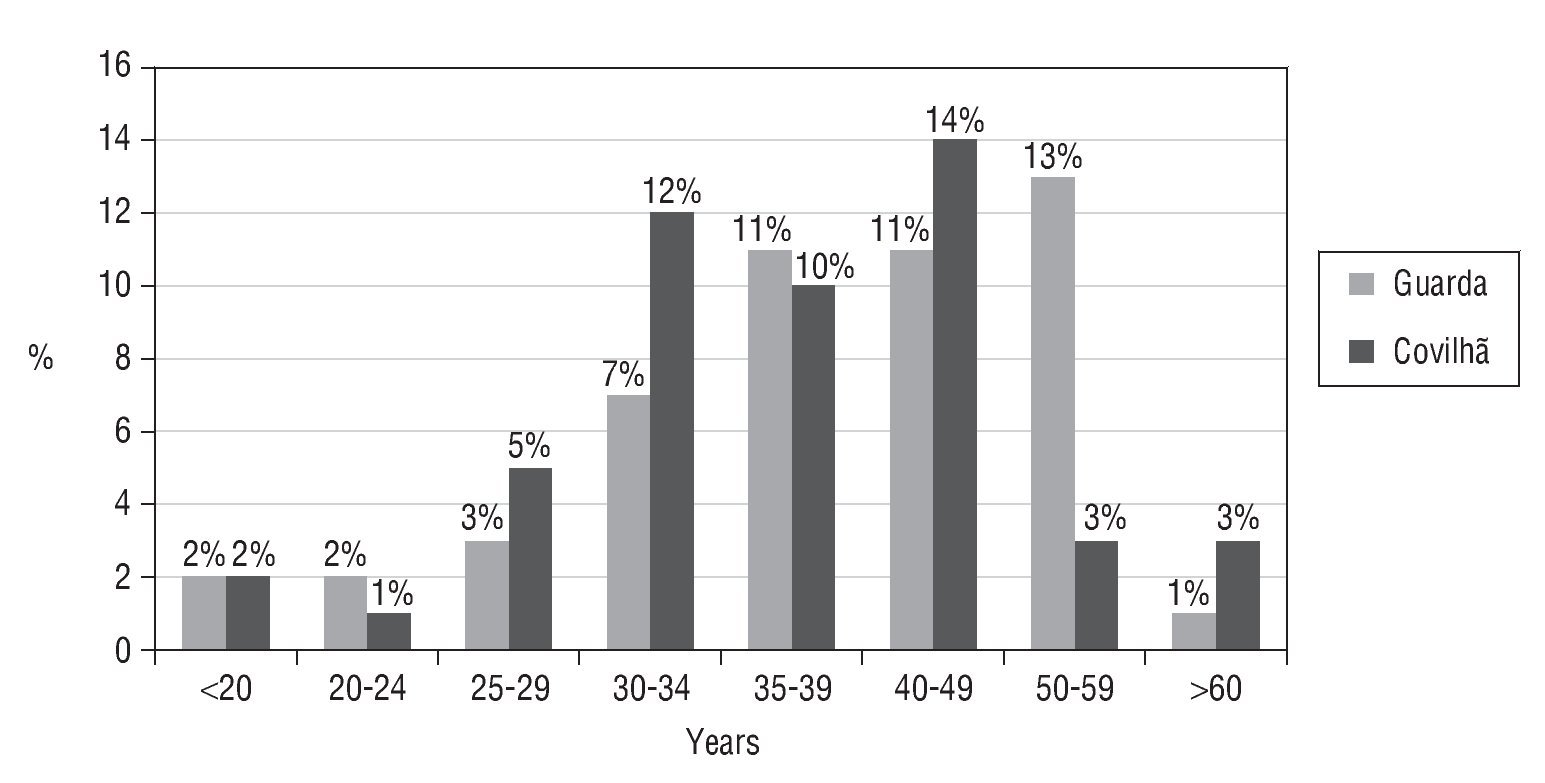

In Figure 4, we can see the results of applying the various formulas for calculating the different dimensions studied by Hofstede (1991).7 Thus, we note that in relation to the hierarchical distance,8 scale, the index normally has a value between 0 (small power distance) and 100 (large power distance). According to the results obtained for the city of Guarda this dimension assumes the value of 27.8 and the city of Covilhã 23.4.

Note that a hierarchical distance or high power distance indicates that inequalities in wealth, power and privilege within society are seen as natural and tolerance, while low power distance means that societies are more egalitarian and have a lower tolerance for inequality in this distribution (Hofstede, 1991).

Regarding the individual dimension,9 the index usually takes a value ranging from 0 (strongly collectivist) and 100 (strongly individualist). In this dimension, Guarda got a score of 77.8 and Covilhã 66.1, indicating communities tend to be individualistic with Guarda taking on a higher value than Covilhã.

It should be noted that this dimension — Individualism versus Collectivism is associated with the importance attached by members of a society to relations in groups and duty/responsibility to protect the interests of those who are around. It is related to the level of importance that society gives to individual effort and achievement as opposed to the collective achievement of individuals and the relationship between them (Smith et al., 2009). In societies with high individualism prevails individuality and individual rights of people and there are strong ties between individuals, whereas in collectivist societies individuals are integrated into groups and are encouraged to act in accordance with the interests, beliefs and values of the group. In this case, the collective interests override the individual (Hofstede, 1991).

For Hofstede (1991), Masculinity versus Femininity dimension refers to as a society tends to value the division of roles by gender and encourages and rewards as the male role of individuals versus the female role. The male index10 normally has a value between 0 (strongly feminine) and 100 (strongly masculine). In the case of our study can be seen that in both cities feminine values predominate, with relatively low index of masculinity, in the case of the Guarda (21.2) and very low in the city of Covilhã (4.8).

In societies that value the predominantly male role, the roles of man and woman are clearly differentiated there is a predominance of values like self-realization, competitive, financial and material achievement, quest for power and control. On the other hand, in societies in which there is a predominance of feminine values, there is a greater concern with quality of life, solidarity and the protection of the weakest. In societies with a predominance of the characteristics of masculinity, work is seen as an end, a way of life, while in societies with a predominance of female characteristics, this is seen as a means to reach the greater goal.

The control of uncertainty dimension is related to the degree of acceptance and preparing society to tolerate uncertainty, ie, reflects how much is or is not prepared to deal with unforeseen and unknown situations. The index normally has a value between 0 (weak Uncertainty Avoidance) and 100 (strong Uncertainty Avoidance), but values below 0 and above 100 are technically possible (as stated in the Values Survey Module 1994 Manual of Hofstede).

High levels of control of uncertainty11 indicate that society has a low tolerance for uncertain situations and unpredictable situations. Thus, are associated with a low propensity of individuals to take risks in business. For societies with low levels of control of uncertainty, risk is a value-added business. With regard to the two cities subject of this study, it appears that the city of Guarda has greater resistance to uncertainty (96.4) than Covilhã (71.4). In societies where prevailing rates of poor control of uncertainty, resistance to change is smaller and the greater the propensity of individuals to assume roles that require exposure to risk (Silva et al., 2009).

Finally, the Confucian domain, which holds orientation on long-term versus short term orientation. The index normally has a value between 0 (very short-term orientation) and 100 (very long-term orientation), but values below 0 and above 100 are technically possible (as stated in the Values Survey Module 1994 Manual Hofstede). This dimension12 is directly related to the expected time of return in terms of reward and result of a task. Societies with a predominance of long-term orientation have shown more entrepreneurial than societies with guidance in the short term. In this dimension, identified in this study, Covilhã has a greater focus on the long term (41.4) while the Guarda has a value of (34.1), ie, has a vision for the short-term.

We can conclude that the position of the two cities in this regard is the low hierarchical distance, the high degree of individualism over collectivism, low masculinity and high degree of control and avoid uncertainty. Thus, the control of high uncertainty and low degree of masculinity may be some of the cultural causes which have hindered the development of dynamic innovation and have acted as barriers to entrepreneurship and improved competitiveness in these two cities.

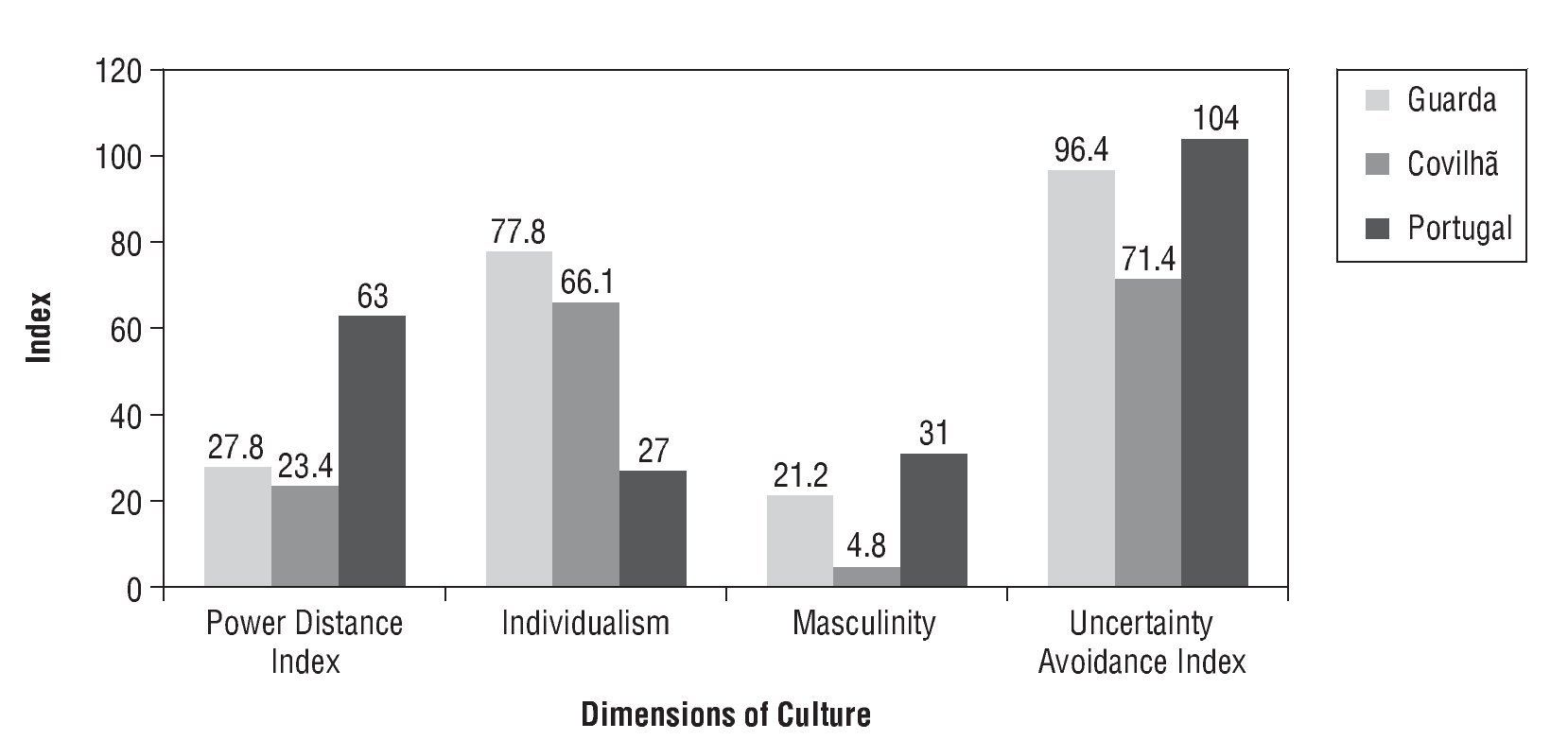

A comparative analysis of the results of the study sample and the ones calculated by Hofstede (1991) for Portugal leads to some interesting conclusions, particularly in the dimension corresponding to the hierarchical distance and individualism, as seen in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5 Comparison between the results and the national study in the city of Guarda and the Covilhã.

The female inclination of these cities will meet the results obtained in the model of Hofstede (1991), for the Portuguese culture (Figure 5): "Portugal is typically Latin, which belongs to the more feminine. However, it is recognized immediately that the Portuguese differ from other Latin countries and unlike the Spanish did not kill his bulls. The Portuguese are more friendly to people and are good negotiators." The traditional Portuguese culture has a principal orientation to femininity, showing a preference for the relationship between subject and caring for the weak.

The same goes for the control of uncertainty, where Portugal and also the cities studied have a very vertical organizational stratification and a high need for "control of uncertainty." These two figures are linked to national characteristics that are the basis of some structural problems: lack of initiative, bureaucracy, stratified and time consuming processes of decision, childish and irresponsible.

Portuguese culture reveals a strong orientation to avoid situations of uncertainty. The institutions, laws and rules are ways to increase security by acting as a protection against the unpredictable human behavior. The only problem is to make these means efficient, because the State is weak and always imagined by citizens as an abstract reality.

In Portugal, contrary to the cities studied, the power tends to be centralized and distributed unevenly. Traditionally, this situation appears to meet the psychosocial needs of protection and a possible dependence of the majority of people without power. People tend to imagine the central government as an abstract reality, distant from the needs of individuals (Hofstede, 1991). In contrast to the cities of Guarda and Covilhã, in Portugal cultural values dominates collectivism, particularly in isolated or hidden places and at regional/traditional and rural context, where is still possible to see collectivism in action, while in more urban settings individualism emerges.

5. Discussion and conclusions

Culture is a set of values, thoughts and emotions. Culture is acquired, not inherited. It comes from the social environment, not genes, should be distinguished from human nature and personality of each one. Cultural differences between countries and regions can be illustrated and measured through the dimensions of culture. The study of the differences of cultures through cultural dimensions seek to recognize/identify a set of characteristics (beliefs and values) common to certain groups of individuals unite in feeling, in thought and action.

To identify cultural differences between individuals we used the work of Hofstede (1991), seeking to identify cultural patterns of the cities of the Guarda and Covilhã in five dimensions developed by Hofstede: 1-Hierarchical Distance; 2-Collectivism/Individualism; 3-Femininity/ Masculinity; 4-Control of uncertainty; and 5-Confucian Dynamism.

An analysis of the results obtained the following conclusions:

— Both cities have reduced hierarchical distance, which indicate more egalitarian societies, and less conformed to unequal distribution of wealth, power and privilege within society and more intolerant of those privileges;

— In the culture of these cities emerged the high individualism indicating that individuality and individual rights of the people prevail in society, where individual interests override the collective and where individual achievement is valued as opposed to collective achievement;

— In the two cities dominate the values of femininity, highlighting the concern about the quality of life, solidarity and the protection of the weak;

— In their control of uncertainty, the two cities show a strong orientation to avoid the uncertainty, while also maintaining values that indicate a society with low tolerance for uncertainty and that is not prepared for unpredictable situations;

— In Confucian dynamism, we inferred that these cities have a more short-term orientation, for immediate or almost immediate return.

Thus, the high control of uncertainty and low degree of masculinity may be some of the cultural causes that have hindered the development of dynamic innovation and have acted as barriers to entrepreneurship and to the improvement of competitiveness in these two cities.

The development of this work allowed us to contribute to a better theoretical understanding of cultural differences that influence the cultures of countries, regions and can therefore also apply to cities. Allowed the identification of patterns profiles and behavioral standards that show different cultural behaviors, and may help to explain the differences in the dynamic of innovation and the performance of territories.

As limitations of the study we can pointed out the limited number of inquiries answered, which limits certain aspects that can be tested and the small number of cities and the fact that respondents are not contemplated innovation indicators to measure and compare the dynamics of innovation in both cities, although there are a number of studies on the same points that allow some conclusions.

In terms of elements of future research is considered interesting to study other cities or even other countries, or other different levels of territorial aggregation (NUTS II or III). This analysis would be more complete if specified which cities are most innovative and competitive. Finally, its points to the possibility of examining these dimensions, only the enterprise level and relate it to the intensity of innovation of firms. Another important aspect that can be worked out in the near future is to measure the innovativeness of cities, using cultural standards as a component.

1. The GEM is an international study that compares several countries, including Portugal, in a wide range of dimensions; this study aims to measure and evaluate the differences between countries in terms of entrepreneurial activity.

2. This fifth dimension of culture, Confucian dynamism, has not been analyzed in some countries such as Portugal; the first study of Hofstede developed in 1980 and written in Portuguese in 1991.

3. The questionnaire and user's manual can be found at http:// www.geerthofstede.nl/research--vsm/vsm-94.aspx

4. See: http://stuwww.uvt.nl/~csmeets/manual.html (How to use and not to use the VSM 94).

5. According to manual application of the questionnaire.

6. According to manual application of the questionnaire.

7. All indices were calculated according to the methodology defined in the Manual (VALUES SURVEY MANUAL MODULE 1994) developed by Geert Hofstede, constant: http://geerthofstede. com/media/312/Manual% 20VSM94.doc

8. Formula for calculating the PDI = -35 m (03) m + 35 (06) m + 25 (14) - 20 m (17) - 20.

9. Formula for calculating the IDV = -50 m (01) + 30 m (02) + 20 m (04) - 25 m (08) + 130.

10. Formula for calculating the MAS = 60 m (05) - 20 m (07) + 20 m (15) - 70 m (20) + 100.

11. Formula for calculating the UAI = 25 m (13) + 20 m (16) - 50 m (18) - 15 m (19) + 120.

12. Formula for calculating the LTO = 45 m (09) - 30 m (10) - 35 m (11) + 15 m (12) + 67.

Received 30 May 2011; accepted 20 January 2012

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address:

m.natario@ipg.pt (M.M. Santos Natário).

References

Aaker J., & Williams P. (1998). Empathy versus pride: the influence of emotional appeals across cultures. Journal Consumer Research, 25, 241-261.

Aaker, J. (2000). Accessibility or diagnosticity? Disentangling the Influence of Culture on Persuasion Processes and Attitudes. Journal of Consumer Research, 26 (4), 340-357.

Adler, N. (1986). International dimensions of organizational behaviour. PWS-Kent Publishing Company. Boston, MA. Albers-Miller, N. D., & Gelb, B. B. (1996). Business advertising: appeals as a mirror of cultural dimensions: a study of eleven countries. Journal of Advertising, 25, 57-70.

Bearden, W. O., Money, R. B., & Nevins, J. L. (2006). Multidimensional versus unidimensional measures in assessing national culture values: The Hofstede VSM 94 example. Journal of Business Research,59, 195-203.

Bilhim, J. A. F. (2006). Gestão estratégica de recursos humanos (2nd ed.). Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas, Lisboa.

Blodgett, J. G., Bakir, A., & Rose, G.M. (2008). A test of the validity of Hofstede's cultural framework. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 25/6, 339-349.

Bond, M. H. (2002). Reclaiming the individual from Hofstede's ecological analysis-a 20-year odyssey: comment on Oyserman et al (2002). Psychological Bulletin, 128, 73-7.

Brück, F., & Kainzbauer, A. (2000). Cultural standards Austria-Hungary. Journal of Cross-cultural Competence and Management, Vienna/Copenhagen, 2, 73-104.

Brück, F., & Kainzbauer, A. (2002). The cultural standards method; a qualitative approach in cross-cultural management research, European Management Research: Trends and challenges. Working paper. Center for International Studies, Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration.

Brück, F., & Kainzbauer, A. (2009). The contribution of autophotography for cross-cultural knowledge transfer. European Journal of Cross-Cultural Competence and Management, 1, 77-96.

Carmo, H., & Ferreira, M. M. (2008). Metodologia da investigação — Guia para a auto-aprendizagem (2nd ed.). Universidade Aberta, Lisboa.

Dosi, G., Freeman, C., Nelson, R., Silverberg, G., & Soete, L. (Eds.), (1988). Technical change and economic theory. Printer, London.

Fink, G., & Meirewert, S. (Eds.) (2001). Interkulturelles management: Österreichische perspektiven. Springer, Wien/New York.

Fink, G., Kölling, M., & Neyer, A. K. (2005). The cultural standard method. EI Working Paper, Nr. 62 January 2005.

Gannon, M. (1994). Understandingglobal cultures: Metaphorical journeys through 17 countries. Sage Publications, London.

George, G., & Zahra, S. (2002), Culture and its consequences for entrepreneurship. A review of behavioral research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26, 5-8.

Gouveia V.V., Clemente M., & Espinosa P. (2003). The horizontal and vertical attributes of individualism and collectivism in a Spanish population. Journal of Social Psychology, 143, 43- 63.

Gurhan-Canli Z., & Maheswaran D. (2000). Cultural variations in country-of-origin effects. Journal Marketing Research, 37, 309-17. Hall, E., & Hall, M. (1990). Understanding cultural differences: keys to success in West Germany, France, and the United States. Intercultural Press, Yarmouth.

Hayton, J., George, & G., Zahra, S. (2002). National culture and entrepreneurship: a review of behavioral research. Entrepreneur ship Theory and Practice, 26, 33-52.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's Consequences: International differences in work related values. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Hofstede, G. (1987). Culture and organizations: software of the mind. McGraw-Hill, United Kingdom.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Culturas e organizações, compreender a nossa programação mental. Edições Sílabo, Lda., Lisboa.

Hofstede, G. (1994). Cultural constraints in management theories. International Review of Strategic Management, 5, 27-48.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's consequences: comparing values, behaviours, institutions, and organizations across nations. Sage Publications. Thousand Oaks, California, London.

House, R., Hanges, P., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P., & Gupta, V. (Eds.) (2004). Culture, leadership and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 countries. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

House, R., Javidan, M., Hanges, P., & Dorfman, P. (2002). Understanding cultures and implicit leadership theories across the globe: an introduction to project GLOBE. Journal of World Business, 37, 3-10.

Inkeles, A., & Levinson, D. J. (1954). National Character: the study of modal personality and sociocultural systems. In Lindsey, G., & Aronson, E. (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (2nd ed.). V. 4. Addison-Wesley, Reading MA.

Internet: www.google.pt: A cultura, os seus padrões e a inovação [accessed 2010 Jan 23]; www.geert-hofstede.com [accessed from 2010 Jan 10 to 2010 Feb 8].

Kluckhohn, F. R., & Strodtbeck, F. L. (1961). Variations in value orientations. Elmsford, Row, Peterson and Company, New York. Laroche, M., Kalamas, M., & Cleveland, M. (2005). I versus 'we': how individualists and collectivists use information sources to formulate their service expectations. International Marketing Review, 22, 279-308.

Lundvall, B. Ä. (1992). National systems of innovation — Towards a theory of innovation and interactive learning. Printer Publishers, London and New York.

Makino S, & Neupert K. E. (2000). National culture, transaction costs, and the choice between joint venture and wholly owned subsidiary. Journal International Business Studies, 31, 705-13.

Müller, S., & Gelbrich, K. (2004). Interkulturelles Marketing. Vahlen, München.

Parsons, T., & Shils, E. (Eds.) (1951). Toward a general theory of action. Harper & Row, New York.

Raman, A. P. (2003). The global brand face-off. Harvard Business Review, 81, 35-46.

Rawwas, M., Patzer, G., & Vitell, S. (1998). A cross-cultural investigation of the ethical values of consumers: The potencial effect of war and civil disruption. Journal of Business Ethics, 17 (4), 435-448.

Rebelo, J., Mendes, F., Rego, C., & Magalhães, M. (2009). Imigrantes cabo-verdianos em Portugal: integração e sua percepção em relação aos portugueses. In Actas do XV Encontro da APDR. Realizado em Cabo-Verde, Julho, APDR, 3457-3482.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. Free Press, New York.

Santos, F., & Reis, E. (2005). Valores associados à globalização. Economia Global e Gestão, vol. X, Quadrimestral, Dezembro, nº 3, 9-29.

Schumpeter, J. (1934). The theory of economic development. MA Harvard, University Press, (Reproduced, New York 1961), Cambridge.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical test in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 23, 1-65.

Schwartz, S. H., & Ros, M. (1995). Values in the West: a theoretical and empirical challenge to the individualism/collectivism dimension. World Psychology, 1, 91-122.

Selnes F., Jaworski B. J., & Kohli A. K. (1997). Market orientation in U.S. and Scandinavian companies: a cross-cultural study. Report No. 97-107, Marketing Science Institute, Cambridge, MA.

Silva, M. A. O. M., Gomes, L. F. A. M., & Correia, M. F. (2009). Cultura e orientação empreendedora: uma pesquisa comparativa entre empreendedores em incubadoras no Brasil e em Portugal. Revista de Administração Contemporânea, 13 (1), Curitiba Jan./Mar. 2009. On-line version ISSN 1982-7849.

Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., & Sparks, K. (2001). An international study of the psychometric properties of the Hofstede value survey module 1994: a comparison of individual and country/ province level results. Review International of Psychol Appl, 50, 269-281.

Tan, J. (2002). Culture, nation, and entrepreneurial strategic orientations: implications for an emerging economy. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26, 95-111.

Thomas, A. (1993). Kulturvergleichende Psychologie — Eine Einführung. Hofgrefe, Göttingen.

Thomas, A. (1996). Psychologie interkulturellen Handelns. Hogrefe, Göttingen.

Thomas, A. (Hrsg.). (1988). Interkulturelles Lernen im Schüleraustausch (SSIP-Bulletin Nr. 58). Breitenbach, Saarbrücken.

Triandis, H. C. (1994). Culture and social behavior. McGraw Hill, New York.

Triandis, H. (1995). Individualism & collectivism. Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado.

Trompenaars, F. (1993). Handbuch globales Managen, Wie man kulturelle Unterschiede im Geschäftsleben versteht. Econ-Verl., Düsseldorf.

Trompenaars, F., & Hampden-Turner, C. (1998). Riding the waves of culture: understanding cultural diversity in global business. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Tse D. K., Lee K. H., Vertinsky I., & Wehrung D. A. (1988). Does culture matter? A crosscultural study of executives' choice, decisiveness, and risk adjustment in international marketing. Journal of Marketing, 52, 81-95.

Tylor, E. B. (1920). Primitive culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art, and custom (6th ed.). Forgotten Books. Free Books. www. forgottenbooks.org

Yin, R. K. (2002). Estudo de caso. Planejamento e métodos. Porto Alegre: Artmed, tradução do original de 1994, Case study research: design and method, Sage Publications.

Zhang, Y., & Gelb, B.D. (1996). Matching advertising appeals to culture: the influence of products' use condition. Journal of Advertising, 25, 29-46.