Adverse events are a reality in health care, with particular interest in the surgical patient, so it is crucial that one knows its dimension, in order to avoid them whenever possible. The internalization of a culture of safety as a priority, by professionals, can contribute to the development of systems that lead to safer care. It can be reduced the occurrence of events and their negative impacts, especially during the hospitalization days and on the additional costs associated. Thus, we developed an exploratory study in a Local Health Unit, with the aim of understanding the culture of safety in surgical services for the year 2008, and if it was influenced by three dimensions: leadership, teamwork and communication. The obtained results show that the security culture is influenced by all of these three dimensions, observing that the existing culture on such services is at an intermediate level classified as acceptable.

It is becoming increasingly recognized that the provision of care involves a series of events arising from multiple circumstances and variables that influence health outcomes. These events, are designated as adverse since they are unintended and unwanted, have significant impacts on the health system, either for patients or for professionals, and also for the institutions.

Several studies (Leape et al., 1991; Vicent, Neale, & Woloshynowych, 2001; WHO, 2002; Wilson et al., 1995), reveal that the incidence of adverse events ranges between 3.8% and 16%, of which 48% are associated with surgery. The implications of these events are relevant in terms of increased length of hospital stay, temporary or permanent disability or even death of patients. In addition, they are associated with substantial economic costs. The concern is even greater when it turns out that about half of these events were avoidable.

Thus, for IMS (2013) and Francis (2013) patient safety in general and surgical patients in particular, needs to be reinforced in healthcare units as a priority in order to prevent the occurrence of adverse events, especially when they are avoidable. This design is possible, if there is a strong culture or a common positive safety culture (Francis, 2013) and efforts to develop the implementation of instruments and tools for monitoring and evaluate the causes of the events.

The present study aims to know the overall safety culture associated with surgical patient safety, for the particular case of the Local Health Unit (LHU) of Guarda, EPE. It is also intended identify whether there is a reporting system for adverse events and opportunities for improvement to reduce these adverse situations. In this perspective, we developed an exploratory study in a Local Health Unit, in order to know the culture of safety in existing surgical services for the year 2008, and whether it is influenced by three dimensions of safety culture: leadership, teamwork and communication. The results show that safety culture is influenced by any of these three dimensions, noting that the existing culture in these services is located at an intermediate level, classified as acceptable.

In order to achieve the proposed objectives, it begins by presenting a theoretical part which will be held in the literature review and the theme underlying the formulation of hypotheses and a second empirical part, based on analysis of data obtained through a questionnaire.

2Literature reviewHealth care is a high risk and “complex industry”, involving a large number of people and processes. Health care brings benefits for the patient, but can also cause damage (WHO, 2002). The great warning about this kind of events came in November 1999 when a report was published by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the United States, estimating that between 44 000 and 98 000 people (or more) die each year in hospitals as a result of medical errors which could be avoided or prevented (IOM, 2000).

Leape et al. (1991) in a study conducted in the United States, performed on a sample of 30 195 records identified adverse events in 3.7% of the cases that have resulted in crippling injuries caused by medical treatment. They pointed out complications with medication in 19%, wound infection in 14% and technical complications in 13%. In these cases, about 48% of all events identified are associated with surgery. But more worrying is that about half of these events were avoidable. Once errors are recognized their causes must be analysed so that preventive measures can be applied. Errors are problems that will not go away. Thus, clear definition of clinical responsibilities is needed (Alberti, 2001). It is also necessary that they are clearly identified and communicated within the organization of health care, so they can be monitored and avoided.

In this way would have been avoided suffering for patients and professionals, especially in cases where there were severe disability or death of patients, representing the latter cases, about one third of adverse events detected (Vicent et al., 2001).

In Canada in a study for the year 2000, it was found that the incidence of adverse events occurring in relation to hospital admissions stands at 7.5%. Among the adverse events it is judged that 36.9% could be avoidable and also are verified other dramatic consequences such as the death of patients in 20.8% of cases (Baker et al., 2004).

According to WHO (2002), the economic impact in the UK as a result of adverse events, is situated at a cost of about 2000 million pounds per year as a result of additional hospitalization time and were still paid about 400 million pounds in compensation processes of victims.

In order to pay attention to these concerns about patient safety, WHO initiated in 2002 a series of measures with the international community, this led to the creation of the World Alliance for Patient Safety in May 2004. The principal aim was to implement and strengthen evidence-based systems to facilitate the development of policies and practices for patient safety in all member states (WHO, 2006) and create a common taxonomy on these issues (WHO, 2007).

As a result patient safety refers to freedom from accidental or preventable injuries produced by medical care. Thus, practices or interventions that improve patient safety are those that reduce the occurrence of preventable adverse events (WHO, 2007). Regarding the adverse event it refers to an event which resulted in damage to the patient, implying damage loss of structure or function of the body and/or any deleterious effects arising therefrom (WHO, 2007).

When it relates to patient safety, the aim is to prevent unnecessary damage occurring in patients with the provision of health care, i.e., prevent the occurrence of adverse events (WHO, 2007). In any way, the risk of adverse events and medical errors cannot be completely eliminated, but the knowledge that they acquire about their occurrence, gives the care providers more opportunities to improve the quality of provision (Jonsson & Ovretveit, 2008).

However each phase of care contains a degree of uncertainty. Whether we like or not, there are risks due to side effects of drugs or drug interaction, inherent risks due to medical devices, use of defective or substandard products, human fault or latent failures in the system. The adverse events may then result in care practical problems, resulting from products or devices during the procedures or problems derived from organizational systems (WHO, 2002).

The National Steering Commitee on Patient and Safety (2002) of Canada adds that the ageing population, the resource constraints, the lack of qualified human resources, in addition to the challenges and restructuring within the health care organizations, also pose difficulties for systems, thus contributing to the increased likelihood of adverse events, sometimes with lethal consequences.

It is widely recognized that health care can improve, reducing human errors and system failures, it is necessary to understand the main causes of the problems. However the fact that information about errors in health care is not being obtained and handled routinely, makes it more difficult to find these same problems (Walton, Shaw, Barnet, & Ross, 2005).

However it is not enough to recognize that errors exist. It is also necessary a clear identification and communication within the organization and it is essential to understand its evolution, in the sense that they can be avoided. Report the event is no more than to give it visibility, and it is then necessary to encourage their communication. It is important to create an organizational culture change, based on communication, assertiveness and team training (Lembitz & Clarke, 2009).

According to Francis (2013), a shared positive safety culture requires: shared values in which the patient is the priority of everything done; zero tolerance of substandard care; empowering front-line staff with the responsibility and freedom to deliver safe care; recognizing them for their contribution; and that professional responsibility is accepted and pursued.

Organizational culture comprises the sharing of attitudes, beliefs, values and norms that underlie how the professionals perform certain tasks within the organization (Cunha, Rego, Cunha, & Cardoso, 2007). This sharing applies equally to the culture of patient safety (Sandars & Cook, 2007) that requires effective teamwork and support from organizational leaders to make safety a priority (WHO, 2008a). Vincent (2010) and Francis (2013) are agree with this approach, emphasizing that what is required is strong motivational leadership: maintaining a safety culture, indeed any kind of culture, requires leadership, ongoing work and commitment from everyone concerned.

Regarding the processes of information and communication, it is necessary to encourage participation, understanding and dissemination of information with respect to approach problems with this complexity, as is the safety of patients. This approach clearly requires solutions at various levels, involving changes in systems strategies to solve the problems at source (WHO, 2008b).

In order to assess and compare the safety culture of hospitals also the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) developed a questionnaire in 2004. It was intended to create a database with relevant information about the professionals’ opinion relating to matters of patient safety, medical errors and reporting of events in their organizations, allowing measurement of twelve areas covered by the safety culture (Sorra, Famolaro, Dyer, Dawn, & Khanna, 2008). In these twelve areas stand out open communication about safety issues, feedback and communication about error, the frequency of events reported, the management support for patient safety, non-punitive responses to error and teamwork.

There can be no question about organizations without risk or occurrence of events. What exist are organizations better prepared than others to deal internally with these events, showing greater maturity with regard to safety. As such, high-reliability organizations are not immune to adverse events. The big difference is that they developed the ability to convert these occasional setbacks in strengthening the resilience of the system (Reason, 2000).

Given the above, according to Singer et al. (2003), the organization has an adequate safety culture, when a series of components are perfectly consolidated at various levels between the various units and members thereof, particularly as regards:

- •

The commitment to safety is linked to the highest levels of the organization and translated on shared values, beliefs and behavioural norms at all levels.

- •

Are needed resources, incentives and rewards provided by the organization in order to allow the commitment to occur.

- •

Security is valued as the first priority, even at the expense of the production or efficiency; personnel who makes a mistake is rewarded by being cautious, even having done wrong.

- •

Communication between workers and between different levels of the organization is frequent and sincere.

- •

The unsafe acts are rare, despite high production levels.

- •

There is an openness regarding errors and problems being reported when they occur.

- •

Organizational learning is valued, the answer to a problem is focused on improving the performance of the system instead of individual blaming.

Furthermore, it is important to realize that all these assumptions are critical, provided they lead to actual results, to improve the care and simultaneously avoid increased costs, both from a social standpoint for patients, both from a financial standpoint for health organizations.

3Hypotheses to testThe growing concerns about patient safety have emphasized the need for monitoring, reporting and understanding not only of adverse events but also the phenomenon of “near misse” or “almost accident” (Fragata, 2006; JCAHO, 2003). Thus, organizations should develop systems for reporting adverse events to more easily deal with the data and analyse their causes, so that practitioners can learn from the mistakes and do not repeat them, with possible injury to the patient.

To Balding (2008), although traditionally health professionals pursue high levels of care, fear of legal confrontation and the hospital culture that blames human error, also contributes to the slowness of organizations to recognize and learn from mistakes depending on better care, the commitment of managers and clinicians. As barriers to reporting incidents to emphasize the responsibility of information, fear of disciplinary action, the fear of possible litigation, fear of breaches of confidentiality and fear of embarrassment, fear that “nothing would change” even if the incident were reported, the lack of familiarity with the process and the impact of a culture of blame (Jennings & Stella, 2011).

For learning from mistakes, the incident reporting systems can then be an important tool, since the incidents are actually reported and analysed. However, research shows that many incidents are not reported by health professionals (Pfeiffer, Manser, & Wehner, 2010). The main reason lies in the guilt associated with errors, it is estimated that for every 20 errors occurred, and only one will be declared and known (Fragata, 2006). Furthermore, it should be refered that the error is essentially human (Fragata, 2006; Kantelhardt, Müller, Giese, Rohde, & Kantelhardt, 2011; Reason, 1995).

The errors in medical care can be known through various mechanisms (Shekelle et al., 2013; Shojania, Duncan, McDonald, & Wachter, 2001). The recording of adverse events and incidents is one of the solutions suggested by various authors (Jansma et al., 2010; JCAHO, 2003; Shekelle et al., 2013; Shojania et al., 2001; WHO, 2005), allowing the collection of data on its occurrence. Either way, there seems to be some consensus that a good information system, which obviously includes the registration of incidents, is considered an important step towards improving patient safety, contributing to a safer care (Jansma et al., 2010).

Currently, the reporting systems for adverse events are not widely used, but these can significantly reduce medical errors, detecting problems and should be easy to use, they allow timely feedback and information analysis by experts (Leape, 2002). The lack of systematic analysis of the reported data and the lack of feedback directly to the clinical are aspects that Mahajan (2010) refers to as the greatest barriers to the commitment of clinical report incidents.

The reporting of adverse events/incidents, contributes significantly to detect errors, damage to patients, equipment malfunctions, failures in the processes or other hazards, which must be reported by health professionals (doctors, nurses, administrators and other professionals).

Although usually the communication is being done by professionals, systems must be developed to integrate communications made by patients, relatives or legal representatives, thus having a more comprehensive system (WHO, 2005).

The notion of communication system events is related “to the process and the technology involved in standardization, formatting, communication, feedback, analysis, learning, response and dissemination of lessons learned from the reporting of adverse events” (WHO, 2005: 8). The focus is to create an effective communication system (Walton et al., 2005), non-punitive (Mahajan, 2010) and that prevents the recurrence of incidents (Gupta, Naithani, Brajesh, Pathania, & Apoorva Gupta, 2009).

The information produced by the communication system of events must then be understood in order to contribute to the improvement of patient safety. If that happens then this information will be used as appropriate (WHO, 2008a). In this sense are important, according to WHO (2005) three key elements to a communication system events related to the patient safety: learning from experience arising from the event; produce a visible response and useful, justifying the resources expended and stimulating incident reporting, and use the results of data analysis and research, to formulate and disseminate recommendations for changing care systems.

That information will only be produced if the events are reported, because a communication system can provide warnings about important points and still provide some understanding of the causes (Vicent, 2007).

In fact, the communication aspects are really relevant to a safety culture. Without communication there can be no organization (Cunha et al., 2007). Thus, should be created opportunities for people to express their views freely, this opening should be transferred to the systems that enable all individuals to report and discuss adverse events with a focus on not blaming, without fear of punishment, existing in however the responsibility and accountability of their actions (Sandars & Cook, 2007).

As can be seen the existence of communication systems of events have a significant impact on the quality of patient care. Given the above set up as a first hypothesis:H1 Open communication influences the safety culture.

People can make mistakes; processes and equipment fail at times, being still evident the lack of connection between professionals, systems, procedures and devices, the capacity of practitioners to avoid the damage will be greater, if it is created a safety culture (Hellings, Schrooten, Klazinga, & Vleugels, 2007).

This safety culture is related to organizational culture, because all organizations have a culture that influences how people behave in organizations to which they belong (Sandars & Cook, 2007).

For Cunha et al. (2007: 636), organizational culture corresponds to a “set of values and practices defined and developed by the organization, which is based on a socially constituted system of beliefs, norms and expectations that shape the thinking and behaviour of individuals.” This is of multidimensional nature and can be analysed at the individual, group, organizational and national level.

The internalization of these values and standards by organizational members, through experience, participation, social interaction and exposure to organizational practices, is what makes the cultures be seized, making the learning process lead to the sharing by the collective, that set of assumptions (Cunha et al., 2007).

Can then be synthesized that organizational culture includes the shared attitudes, beliefs, values and norms that underlie how the professionals perform certain tasks within the organization. This sharing is applied equally to the culture of patient safety, as tells us Sandars and Cook (2007). That culture must be a positive safety culture or a shared positive safety culture as defend Francis (2013), i.e., which has the attributes of open communication about safety issues, an effective teamwork and support from organizational leaders to make safety a priority (WHO, 2008a).

The organizations must move towards the implementation of active programmes to improve patient safety, with error monitoring and of damage through practices that prevent the occurrence of major adverse events (Vicent, 2007). The aim is to make the system proactive in search for causative factors (National Steering Commitee on Patient and Safety, 2002).

In this process, it is essential the strong commitment by top management to lead the development of improved patient safety, as well as a clear definition of policies for this purpose. The organization must also have a comprehensive system that provides information on the hazards, which should be positive and effective that rewards people who reach the objectives in relation to patient safety and to be used by everyone. That is why that in this process the manager of the organization plays an important role and should position itself as a leader in building a culture of safety.

To Colla, Bracken, Kinney, and Weeks (2005), the climate of patient safety involves five dimensions: Leadership, Policies and Procedures, Personal, Communication and Information. These dimensions include in a generic way the various aspects that are intertwined in the success of a safety culture, requiring the participation of all involved in the process of improving the safety of patients. To encourage the improvement of patient safety in organizations is then necessary to coordinate the efforts of various members of the health team (Shekelle et al., 2013; Shojania et al., 2001). These efforts require strong leadership to encourage the registration of events and improve communication and coordination between care providers (Baker et al., 2004). It is required a strong motivational leadership, an ongoing work and commitment from everyone concerned (Francis, 2013; Vincent, 2010) to maintain a safety culture, indeed any kind of culture. Given these considerations was established as the second hypothesis:H2 The leadership influences the safety culture in the services.

The health care service has a number of risks and is why it is necessary to create an organizational culture change (Lembitz & Clarke, 2009) that facilitates their reduction. Safety culture is to Pronovost and Sexton (2005), increasingly recognized as one of these strategies to improve the generalized deficit in patient safety therefore involves a professional commitment to the entire organization for safety in which each member holds his own safety and their partners.

The Manchester Patient Safety Framework (NPSA, 2006), designed to help the team to recognize that the patient safety is important, it is a tool that relies on a complex and multidimensional concept, facilitates reflection on the culture of safety and is based on ten dimensions:

- 1.

Commitment to global continuous improvement.

- 2.

Priority given to safety.

- 3.

System errors and individual responsibility.

- 4.

Recording of incidents and good practice.

- 5.

Evaluation of incidents and good practice.

- 6.

Learning and implementing change.

- 7.

Communication on security issues.

- 8.

Personnel management and security issues.

- 9.

Education and training of professionals.

- 10.

Teamwork.

Also Sorra, Famolaro, Dyer, Dawn, and Smith (2012), to evaluate the safety culture of hospitals, emphasize openness communication about safety issues, feedback and communication about error, the frequency of events reported the management support for patient safety, the not punitive answers to error and teamwork.

In addition to communication, the safety and the quality of health care given to the patient also depends on a working environment of collaboration and teamwork (JCAHO, 2008). The way team members communicate, support or supervise each other, limits and influences individual practices and their impact on the patient. However, the team is affected by the actions of management and the decisions taken at the highest level of the organization (Vicent, Taylor-Adams, & Stanhope, 1998).

Thus, the leaders should foster good teamwork in care. They should ask teams to set challenging and measurable team objectives; facilitate better communication and coordination within and among teams; and encourage teams to regularly take time out to review their performance and how it can be improved (NAGSP, 2013).

The performance of the health care team is also affected by certain disruptive behaviours, which include ostensive actions such as verbal outbursts and physical threats or passive actions such as refusal to perform certain tasks or quietly exhibiting uncooperative attitudes. Thus organizations should approach this problem from the viewpoint of ensuring the quality and promote safety culture and develop training to all team members (JCAHO, 2008).

Besides, to Francis (2013) most service provision in an acute hospital setting is the result of teamwork and often the work of more than one team, emphasizing the team-working role as a means of multidisciplinary that offers great opportunities for effective communication, information sharing and joint learning through active participation of all members.

The training associated with the implementation of small changes in procedures, equipment, supervision, on teamwork and organization, promotes the establishment of a strong safety culture and amazing effective practices (Leape, Berwick, & Bates, 2002).

A culture of safety in healthcare organizations is multidimensional, requiring adequate communication, teamwork and effective collaboration, a sharing of values, beliefs, experiences and knowledge and a strong commitment of the leader, to whom the surgical area can not be strange. Given these considerations was established the following hypothesis:H3 The teamwork influences the safety culture.

For this study we chose to use a questionnaire which was developed, based on various questionnaires used in the United States by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Sexton et al., 2006). For the construction of the questionnaire, we used the methodology proposed by Hill and Hill (2000: 81), translate – translate back, since the original questionnaires were validated to the English language, being necessary to check in terms of language if they were appropriate to the target population.

For the validation of the questionnaire, it was conducted a pre-test with the application to 6 nurses and 4 doctors according to Fortin (2009), selected by convenience between days 01 and 03 April, 2009. After the introduction of suggested corrections it was applied the re-test to 4 doctors and 6 nurses, who were in service, between days 13 and 16 April, 2009. We went into the final implementation of the questionnaire after analysing the results of the re-test because the respondents did not have more relevant questions.

The study population consists of 196 subjects (161 nurses and 35 doctors), who directly work in the surgical area of the ULS of Guarda, to who was administered the questionnaire. Data collection took place between May 4 and June 4, 2009, having been collected 132 questionnaires filled out properly and that are the sample of this study.

The methodology used here is based on the application of multivariate statistical inference, through clusters analysis, to see how are ordered the health professionals regarding their behaviour in culture of patient safety and in order to group them according to their attitude.

The clusters analysis allows to group individuals into homogeneous groups because each observation is much more similar among its members, the more different is in relation to the observations belonging to other clusters, that is, the grouping is made from measurements of similarity or measures of dissimilarity (Marôco, 2010).

To group the individuals can be used hierarchical methods or non-hierarchical methods. The choice for this study fell on the non-hierarchical method K-means, as it relates Pérez (2001), this model affects cases to differentiated groups without relying each other. Each case belongs to a group, and one requiring that the dispersion formed within each group is as low as possible: the variance criterion.

In order to validate the assumptions regarding the population is necessary to perform certain statistical tests from the observed data. In this way the hypothesis tests allow inferring the population parameter being associated with this process a given significance level, having as objective refute a given hypothesis regarding one or more parameters of the population (Marôco, 2010). To check the hypotheses formulated we resorted to the application of multiple comparison tests of means to assess the unique characteristics of each cluster.

5ResultsTo examine the safety culture in USL of Guarda were used the results obtained by the questionnaire. The study sample represents 67.3% of the target population. In general it is mostly made up of female elements, with 71.8%, corresponding to 28.2% of male respondents.

As to the profession, is constituted by 105 nurses (80.8%) and 25 doctors (19.2%). This difference corresponds to the originally anticipated, since the more representative professional group is of nursing compared to the health care physicians group, as seen in the data of Direção Geral de Saúde (DGS, 2010), as well as in the figures in terms of inclusion of subjects in the target population. It was also found that two respondents who answered the survey did not indicate their profession.

With respect to age, the class of 31–40 is the most representative (37.1%) followed by the class of 41–50 years (33.3%). We can then see that about 70% of the respondents of this study are between 31 years and 50 years of age.

As for length of service, it appears that the ruling class is one in which the individuals have a service time exceeding 21 years, corresponding to 28.9% of total respondents. With regard to length of service in current unit where professionals play functions, it appears that is between 1 and 5 years of service that puts the most representative group with 33.9%, followed by the class 11–15 years represented by 20.5% of the individuals. Note also that 5 individuals did not indicate their service time.

One important aspect of this study is to understand the existence of a system of adverse event reporting. The results of study show that 72.9% of the individuals say there is no system of adverse event reporting and only 27.1% of respondents note the existence of this system.

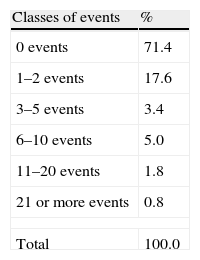

These results are in line with the responses regarding the quantification of the number of events that each subject carried out in 2008 (Table 1). It is found that 71.4% of respondents reported not having provided any event this year and only 17.6% reported 1–2 events, and other data of little significance, since none of the other classes exceeds 5%. Also note that 13 respondents did not make any mention of the number of events reported.

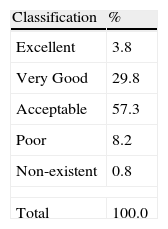

With a view to realize the classification given by each respondent to the unit where performs functions, given the general assessment of the safety of the patient was defined a rating of 5 levels, Excellent, Very Good, Acceptable, Poor and Non-existent (Table 2).

This classification had a variable distribution from 1 respondent who claims to be “None” to 5 subjects who reported being “Excellent”. To examine this issue (Table 2), it appears that the majority of respondents (57.3%) ranked their unit as “Acceptable”, followed by 29.8% who consider their unity “Very Good” with respect to patient safety. One respondent did not answer this item.

After the presentation of descriptive data, is needed to better understand the phenomenon under study, so it is followed by the hypotheses test.

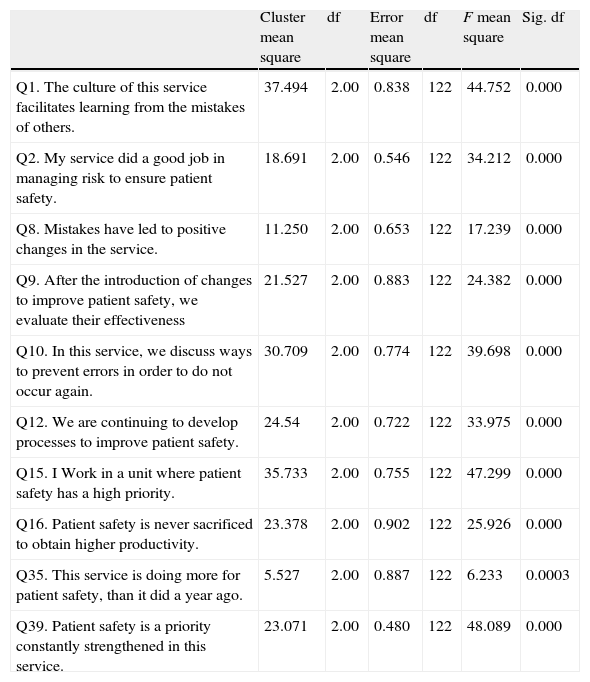

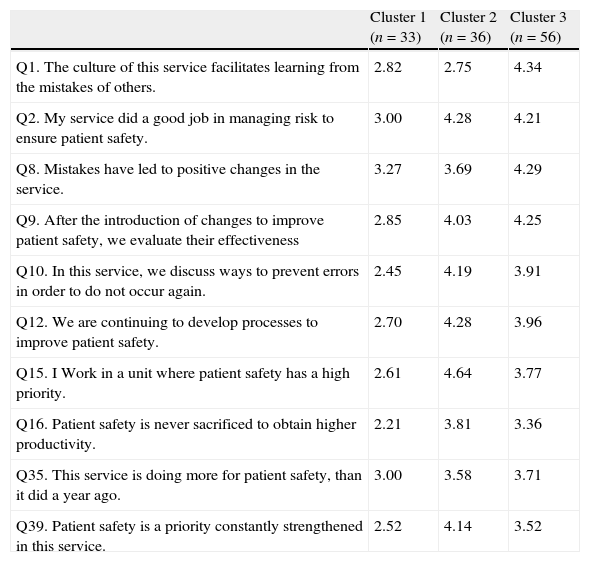

The use of the methodology described above has proved being successful, since the variables used to classify the subjects in terms of “Safety Culture”, were all significant, as can be seen by the results of the ANOVA, shown in Table 3.

ANOVA analysis for safety culture.

| Cluster mean square | df | Error mean square | df | F mean square | Sig. df | |

| Q1. The culture of this service facilitates learning from the mistakes of others. | 37.494 | 2.00 | 0.838 | 122 | 44.752 | 0.000 |

| Q2. My service did a good job in managing risk to ensure patient safety. | 18.691 | 2.00 | 0.546 | 122 | 34.212 | 0.000 |

| Q8. Mistakes have led to positive changes in the service. | 11.250 | 2.00 | 0.653 | 122 | 17.239 | 0.000 |

| Q9. After the introduction of changes to improve patient safety, we evaluate their effectiveness | 21.527 | 2.00 | 0.883 | 122 | 24.382 | 0.000 |

| Q10. In this service, we discuss ways to prevent errors in order to do not occur again. | 30.709 | 2.00 | 0.774 | 122 | 39.698 | 0.000 |

| Q12. We are continuing to develop processes to improve patient safety. | 24.54 | 2.00 | 0.722 | 122 | 33.975 | 0.000 |

| Q15. I Work in a unit where patient safety has a high priority. | 35.733 | 2.00 | 0.755 | 122 | 47.299 | 0.000 |

| Q16. Patient safety is never sacrificed to obtain higher productivity. | 23.378 | 2.00 | 0.902 | 122 | 25.926 | 0.000 |

| Q35. This service is doing more for patient safety, than it did a year ago. | 5.527 | 2.00 | 0.887 | 122 | 6.233 | 0.0003 |

| Q39. Patient safety is a priority constantly strengthened in this service. | 23.071 | 2.00 | 0.480 | 122 | 48.089 | 0.000 |

Through the analysis of ANOVA F-statistics, as described in Marôco (2010), it was found that the Question 39 is apparently which allows to better differentiate the clusters (F=48.089), while the Question 35 is the one which less differentiates them (F=6.233).

The application of Clusters analysis allowed distinguishing three clusters with different security cultures (Table 4).

Clusters’ constitution.

| Cluster 1 (n=33) | Cluster 2 (n=36) | Cluster 3 (n=56) | |

| Q1. The culture of this service facilitates learning from the mistakes of others. | 2.82 | 2.75 | 4.34 |

| Q2. My service did a good job in managing risk to ensure patient safety. | 3.00 | 4.28 | 4.21 |

| Q8. Mistakes have led to positive changes in the service. | 3.27 | 3.69 | 4.29 |

| Q9. After the introduction of changes to improve patient safety, we evaluate their effectiveness | 2.85 | 4.03 | 4.25 |

| Q10. In this service, we discuss ways to prevent errors in order to do not occur again. | 2.45 | 4.19 | 3.91 |

| Q12. We are continuing to develop processes to improve patient safety. | 2.70 | 4.28 | 3.96 |

| Q15. I Work in a unit where patient safety has a high priority. | 2.61 | 4.64 | 3.77 |

| Q16. Patient safety is never sacrificed to obtain higher productivity. | 2.21 | 3.81 | 3.36 |

| Q35. This service is doing more for patient safety, than it did a year ago. | 3.00 | 3.58 | 3.71 |

| Q39. Patient safety is a priority constantly strengthened in this service. | 2.52 | 4.14 | 3.52 |

Cluster 1 was comprised of 33 health professionals was classified as having a behaviour more “poor” in terms of safety culture, as it features the lowest values for most of the items selected to define this culture.

Cluster 2 comprised 36 professionals, is what has the best behaviour in terms of safety culture, so it was classified as having a “Very Good” culture. Cluster 3, consisting of 56 elements was classified as having a reasonable culture that corresponds to the level “Acceptable”.

It is noted that the Cluster 2 and Cluster 3 have very similar results, however it was considered that Cluster 2 shows a better performance, since in most items that constitute the culture dimension of security, this achieves better results, except in the aspect related to learning from mistakes, which features a lower score, and is due to the fact that this aspect is not properly internalized by the group.

After this initial analysis, one relies on the application of multiple average comparison tests of group to interpret how they established the relationship between the explanatory variables and the dependent variable “Safety Culture”, i.e., to test the hypotheses.

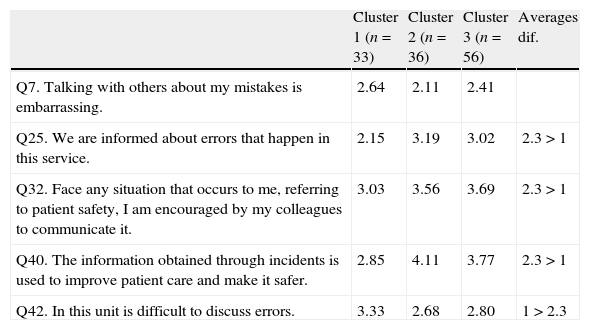

5.1Hypothesis 1H1a Open communication influences the safety culture in the services. Open communication does not influence the safety culture in the services.

Relative to the dimension “Communication”, it turns out that all variables are significant with the exception of Question 7, because it presents p=0.07 for a significance level of 0.05.

According to Table 5, it appears that the Cluster 2 stands up relative to others, especially as in what regards the use of the information on incidents and the improving of safety on patient care. For the other items, the results are relatively close, keeping however Cluster 1 with the worst results, with the exception of Issue 42, however, as they refer to reveal aspects of a less positive culture which means fewer results achieved.

Mean differences among groups – open communication.

| Cluster 1 (n=33) | Cluster 2 (n=36) | Cluster 3 (n=56) | Averages dif. | |

| Q7. Talking with others about my mistakes is embarrassing. | 2.64 | 2.11 | 2.41 | |

| Q25. We are informed about errors that happen in this service. | 2.15 | 3.19 | 3.02 | 2.3>1 |

| Q32. Face any situation that occurs to me, referring to patient safety, I am encouraged by my colleagues to communicate it. | 3.03 | 3.56 | 3.69 | 2.3>1 |

| Q40. The information obtained through incidents is used to improve patient care and make it safer. | 2.85 | 4.11 | 3.77 | 2.3>1 |

| Q42. In this unit is difficult to discuss errors. | 3.33 | 2.68 | 2.80 | 1>2.3 |

Thus, as the Cluster 1, with lower safety culture presents worse results for the dimension “Open Communication”, we reject the H1b, and since it appears that the communication affects the safety culture in the surgical services of ULS of Guarda.

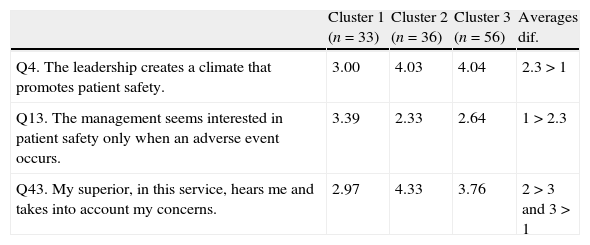

5.2Hypothesis 2H2a The leadership influences the safety culture in the services. The leadership does not influence the safety culture in the services.

From the analysis of Table 6, it can be seen that Cluster 1 having a poorer safety culture has a lower score for all the variables that constitute the dimension “Leadership.” It is noted for the fact that for question 13 of Cluster 1 has the best result, but as the question is in the negative, the best result in terms of safety culture is associated with the lowest value reached (Table 7).

Mean differences among groups – leadership.

| Cluster 1 (n=33) | Cluster 2 (n=36) | Cluster 3 (n=56) | Averages dif. | |

| Q4. The leadership creates a climate that promotes patient safety. | 3.00 | 4.03 | 4.04 | 2.3>1 |

| Q13. The management seems interested in patient safety only when an adverse event occurs. | 3.39 | 2.33 | 2.64 | 1>2.3 |

| Q43. My superior, in this service, hears me and takes into account my concerns. | 2.97 | 4.33 | 3.76 | 2>3 and 3>1 |

Mean differences among groups – teamwork.

| Cluster 1 (n=33) | Cluster 2 (n=36) | Cluster 3 (n=56) | Averages dif. | |

| Q24. The doctors and nurses work as a team well-coordinated. | 2.12 | 3.03 | 2.98 | 2.3>1 |

| Q28. I am satisfied with the quality of collaboration that I have obtained from the medical team of this service. | 2.72 | 3.34 | 3.25 | 2.3>1 |

| Q29. I am satisfied with the quality of collaboration that I have obtained from the nursing staff of this service. | 3.63 | 4.09 | 4.02 | 2.3>1 |

| Q30. This service develops a good job in training new staff. | 2.70 | 3.83 | 3.93 | 2.3>1 |

Thus we conclude that the clusters with greater safety culture are those that present best performing for the dimension “Leadership.” Thus we reject H2b, i.e., leadership influences the culture of safety in the surgical services of ULS of Guarda.

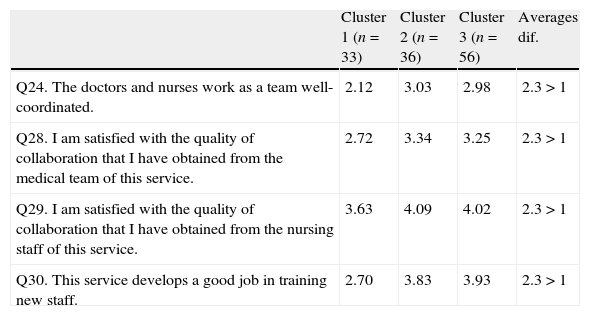

5.3Hypothesis 3H3a The teamwork influences the safety culture. The teamwork does not influence the safety culture.

Regarding the “Teamwork”, the differences between groups are more significant for coordination between nurses and doctors and the training of new staff, checking that the Cluster 2 obtains the best result for Question 24, while Cluster 3 obtains the best result for question 30.

Also for this dimension, it is found that the cluster with a poorer safety culture gets the worst results, so we consider the rejection of H3b, may infer that the teamwork influences the culture of safety in the surgical services of the ULS of Guarda.

6ConclusionsThis study was developed to understand the role of professionals, since the existing safety culture, allows the measurement of commitment that every professional has before the provision of safe care, as also refer Pronovost and Sexton (2005), by approaching the involvement of all professionals in this commitment.

According to the information supported by the literature, was developed a methodology that determined the collection of data necessary for verification of certain assumptions, the assumptions inherent in the construct, as well as instruments to ensure that the research is in agreement with the frame of reference.

From the obtained results it can be seen that the sample consists essentially of female elements and are represented more nurses than doctors, mostly aged between 31 years and 50 years. The predominant service time is above 21 years, but we note a large turnover for services, since the service time in the unit, where they perform functions, is between 1 and 5 years.

As for occupation, the existence of a larger number of nurses (105) compared to the number of doctors (25) is due to the fact that nurses are usually the professional class with more members in hospitals, as it can be seen in the numbers presented by DGS (2010).

Most professionals consider their unit as acceptable with regard to patient safety, and this fact coincides with the results obtained for the clusters, as the most representative group with 56 elements, presents an intermediate score for safety culture.

These results show that the culture of safety in surgical services in ULS of Guarda, falls short to the health services, and the fact that mostly of the respondents were located in an intermediate position, may reveal the non-existence of a positive safety culture, according to the principles set out by the WHO (2008b) and Francis (2013), properly rooted in organizational culture.

This assessment is also based on the fact that the results are substantially different from those observed by Sorra et al. (2008) as in the study conducted by the authors it was found that 48% (the majority) of respondents ranked their unit as “Very Good”.

Another aspect, that also contributes to the finding of a positive safety culture, is learning from mistakes, point made by some authors as Leape (2002), WHO (2008b), Vincent (2010) and Francis (2013) so that these might be corrected and do not recur.

These data, associated with the fact that 71.2% of respondents believe that clinical errors are not properly treated in their unit, implies a serious reflection about the path that will be needed to walk in order that the culture of safety and intrinsically the patient safety may improve their levels.

These data show that the effort for improvement falls short of desirable because as stated Vicent et al. (1998), the non-recognition of faults, provides the necessary conditions for the occurrence of unsafe acts.

It was found that the variables used for the dimensions considered for this study were all significant for a confidence interval of 95%, with the exception of one concerning the communication dimension, thereby strengthening the decision-making on the hypothesis made. It is noted also that there are differences between the three groups with respect to their averages, about the dimension of the safety culture.

Thus, it appears to validate all hypotheses, i.e. the culture of safety in the surgical services of the ULS of Guarda is influenced by leadership, teamwork and communication. It is noticed that the existing culture does not reach high levels, but nevertheless there are positive aspects such as the fact that 62.5% of respondents consider that the existing procedures and systems are good at preventing errors.

Learning from mistakes, another factor essential to the development of a high safety culture, it is not very noticeable, since 89.3% of respondents recognize that the error is a real and significant risk, but 43.1% of the individuals, does not agree that the unit to which they belong, facilitates learning from the mistakes of others.

Regarding the reporting of events, this is manifestly deficient because it does not appear that there are incentives for reporting events, since 71.4% of respondents did not report any event in 2008. Associated with this result, it is found that there is not an events communication system implemented and effective.

These results are significantly different from those referenced by Sorra et al. (2008), because they present lower values, although still significant, once in the above study, 52% of respondents did not perform any communication about the occurrence of adverse events.

However the data are consistent with Fragata (2006) and Pfeiffer et al. (2010), who described that adverse events are not reported according to their occurrence. It is estimated that the incidence of adverse events is greater than those actually communicated.

Although several authors (Armitage, Newell, & Wright, 2010; Jennings & Stella, 2011; WHO, 2008a), denote as causes for not reporting events by professionals, the fear of litigation or reprisal, fear of disciplinary action, or the fact that communication is seen as a personal attack, it is considered that in the case of the ULS of Guarda, the most important, is the fact of not being properly implemented a communication system for this purpose.

The event reporting is integrated in a more embracing process, which is organizational communication, this being one of the dimensions of safety culture, as regards Sorra et al. (2008), and so it is important to understand the relationship of the dimensions tested with culture safety.

With regard to communication, it was proved that this fact influences the culture of safety, because good communication, greater openness in the discussion of errors and better information about them, allows better care, so the culture of safety is also greater.

This is also reiterated by the NPSA (2006) and WHO (2008b), referring to communication as a key to reducing errors, facilitating learning from the experiences of others (whether good or bad), thus improving safety culture. It can be stated that a poor communication corresponds to a poor culture.

Finally, as regards to the dimensions studied, it was also proved that the teamwork influences the culture of security, since the culture groups with higher safety match higher values of this magnitude, i.e., an environment where exists the involvement of all, creates a safer surrounding, as also refers Shojania et al. (2001).

This aspect is corroborated by Vicent et al. (1998), NAGSP (2013) and Francis (2013), when they refer that for the existence of a culture of safety, it is necessary that each member of staff realizes that they are a part of a team and the way they exercise care practice is influenced by other elements through the way they communicate and support.

All these notes are important aspects of organizations in an evolutionary perspective, we want it to result in concrete improvements for the performance of professionals and systems at the same time should open new perspectives and approaches on the issue, despite certain limitations that may be evidenced.

This work was supported by UDI/IPG – Research Unit for Development of Inland, PEst-OE/EGE/UI4056/2014.