Although organizational innovativeness has been regarded as propelling the market, entrepreneurial and learning orientation, as well as innovativeness relationships, much of the evidence to date remains anecdotal and speculative. In other words, little is known empirically about how these orientations contribute to a firm innovation. This leads to reductionism in modeling and thwarts the full exploration of the potentially multifaceted relationships among these concepts and their impact on firm innovation. In this context, a systematic framework was devised which tested the postulated market, entrepreneurial and learning orientations relationships collectively, their effect on innovativeness and the subsequent effect of innovativeness on business performance. Utilizing a sample of 238 Swiss watch manufacturing firms, we empirically examine the antecedents of firm innovativeness in this context. The findings confirm the validity of the model and afford various insights on the role of innovativeness and the impact it has on business performance in the proposed relationships. Finally, implications are shown for the antecedents and consequences of organizational innovativeness.

Considerable progress has been made in identifying each avenue leading to a competitive advantage in marketing as well as the bottom-line consequences of their orientations. The next challenge is to understand how the emerging capabilities approach strategic management (Day, 1994; Hult, Ketchen, & Arrfelt, 2007; Pepe, Abratt, & Dion, 2012; Tajeddini, Ulf, & Trueman, 2013) and cultural competitiveness variables (Hult, Snow, & Kandemir, 2003) can offer a rich array of ways to design changing programs that will enhance a business performance. Henri (2006) for example, examines four of these capabilities, namely market orientation, entrepreneurship, innovativeness and organizational learning, which lead an organization to strategic choices. He argues that these variables are recognized as primary capabilities to reach competitive advantage, to match and create market change.

Notwithstanding an extensive and diverse literature, concerning these capabilities, innovativeness remains the phenomenon that is the most emphasized yet least understood by scholars in different disciplines (Tajeddini & Tajeddini, 2012). Drucker (1954) was one of the first to address the importance of innovativeness and stressed its neglect in organizational research. Researchers underline the need to explore innovativeness and its key influential factors from different perspectives. For example, Weerawardenaa and O’Cass (2004) place emphasis on the role of entrepreneurship and innovation, Deshpandé and Farley (2004) stress that some work is needed on the scales measuring innovativeness. Hurley and Hult (1998) note that the relationship among organizational innovation, learning, and market orientation should be examined in more depth and Liu, Luo, and Shi (2003) observe the relationship between market orientation, learning orientation and entrepreneurship as missing links. Woodside (2005) calls attention to a muddling of the definitions of innovativeness.

Despite the large number of studies that have examined innovativeness as a dependent variable which contributes to firm performance (Deshpandé & Farley, 1999; Deshpandé & Farley, 2002; Deshpandé & Farley, 2004; Deshpandé, Farley, & Webster, 1993), studies on the effective factors to innovativeness in the firm have produced different outcomes (Henard & Szymanski, 2001; Tajeddini, 2014). Relatively little is known about the drivers of innovativeness and how those drivers interact with each other and collectively influence innovativeness (Hult, Hurley, & Knight, 2004). While the positional advantage of firms has been suggested to be a function of market orientation, learning orientation, entrepreneurial orientation, and innovativeness, few studies have examined the links among these constructs empirically and in an integrated manner (e.g., Henri, 2006; Hult et al., 2004). As such, we do not know how these constructs interact to influence the firm performance in a world-class manufacturing industry.

Furthermore, in order to increase the level of innovativeness in firms, scholars have identified a number of antecedent conditions and constructs that are related to innovation output. For instance, Hult and his colleagues (2004) argue that among the key antecedents to innovativeness are the constructs of market orientation, learning orientation, and entrepreneurial orientation in the context of varying market turbulence. Moreover, the literature on strategic management (Calantone, Cavusgil, & Zhao, 2002; Hult et al., 2003; Hult, 2002; Hurley & Hult, 1998) suggest that certain relationships tend to hold among learning orientation, market orientation, entrepreneurship, and firm innovativeness. Past research shows that each of these four capabilities is adequate to offer strengths, but is not sufficient to develop sustained advantages (Henri, 2006). Although some remarkable studies have shown that these constructs collectively enable a firm to achieve competitive advantage (for example, Bhuian, Bulent, & Bell, 2005; Hult & Ketchen, 2001; Hult et al., 2004), more evidence in different contexts can support their effects on business performance. Replication studies of these orientations are warranted simply because if these variables are reliable and valid, they should also be applicable in different environments and organizations (Bhuian, 1998). In addition, despite voluminous discussion on each of these constructs, there has not been an empirical study that interrelates these orientations from the perspective of cultural and processes/activities, nor discusses these issues in a context of the world-class manufacturing industry (Liu et al., 2003). Thus, based on a review of relevant literature and theoretical conceptionalizations, this study investigates the influence of three key antecedents namely learning, entrepreneurial and market orientation upon innovativeness in an integrated manner. Overall, this study extends the literature by simultaneously exploring the relationships between innovativeness and other critical constructs and may answer the call for more research on the drivers of innovativeness by Hult et al. (2004). The advantages of these orientations jointly to organizations have been evidently documented in the U.S. companies (Hult et al., 2003; Hult et al., 2004; Lin, Peng, & Kao, 2008), Canadian manufacturing firms (Henri, 2006) and Chinese enterprises (Liu et al., 2003), but void in Swiss firms. In contrast to the single-organization focus of the Hult et al. studies (2003, 2004), we examine innovativeness in the Swiss watch industry to broaden the application of these orientations paradigm at a time when this industry is under increased pressure to sustain against its strong competitors (Tajeddini, 2007, 2011a,b) as well as to contribute to the development of this industry. To address these issues, in this study, we scrutinize the effect of the three key organizational cultural orientations (market orientation, learning orientation and entrepreneurship) on innovativeness in the multiple Swiss watch firms and in return the impact of innovativeness on the performance of Swiss watch manufacturing firms.

2Theoretical background and hypotheses2.1InnovativenessIt seems that there is no real consensus on the meaning of innovativeness, because it is a multi-dimensional composite variable (Nystrom, Ramamurthy, & Wilson, 2002; Tsai & Yang, 2014), composed of radicalness, relative advantage, and the number of innovations adopted. In fact, innovativeness might be conceptualized in different ways depending on which standpoint the research takes (Tajeddini & Tajeddini, 2012). Whose innovativeness is being referred to also varies. For example, Salavou (2004) observes innovativeness in terms of products rather than organization, while Roehrich (2004) examines innovativeness at three levels; (1) product, (2) organization and (3) customer. Wang and Ahmed (2004) utilize the term of organizational innovativeness equivalent with “innovative capability”. Damanpour and Evan (1984) point out: “The adoption of a new idea in an organization, regardless of the time of its adoption in the related organizational population is expected to result in an organizational change that might affect the performance of that organization” (p. 393). In other words, the adoption of innovation is generally intended to contribute to the performance or effectiveness of the firm (Damanpour, 1991; Tajeddini & Trueman, 2011). Based on previous studies, Hult et al. (2004) argue that this variation of thoughts is rooted in how environments evolve and how firms adopt innovations over time; the most important of which are those that allow the firm to achieve some sort of competitive advantage, thereby contributing to its performance. Nevertheless, it is important to understand how managers perceive innovativeness and to identify the key drivers for successful innovation (Tajeddini & Trueman, 2014; Tajeddini & Trueman, in press). Ingram and Fraenkel (2006) argue that an individual's perception can be shaped by culture and values, which in different industries may vary according to each customer as well as employee. Therefore, it is difficult to identify, interpret or measure innovation in practice.

In general, it can be argued that a firm must be innovative to gain a competitive advantage in order to survive and grow (Deshpandé & Farley, 1999; Ngo & O’Cass, 2012; Tsai & Yang, 2014) in a volatile environment (Johnson, Meyer, Berkowitz, Ethington, & Miller, 1997). Peters and Waterman (1982) discovered that excellent companies are innovative in the sense that they are continually responsive to any sort of change occurring in their environments. Deshpandé and Farley (2000, 2002) found that, for a representative sample of Shanghai firms competing in business-to-business markets, success was related to innovativeness, a high level of market orientation, and outward-oriented organizational cultures and climates. On the basis of this discussion, the following is proposed:H1

Higher levels of innovativeness associated with higher levels of business performance measured by: (a) market share; (b) percentage of new product sales to total sales; (c) ROI; (d) number of new products developed.

2.2Innovativeness and market orientationOrganizations who embrace the concept of a market orientation believe it will encourage appropriate behavior for the creation of superior customer value and thus superior business performance (Narver & Slater, 1990; Tajeddini, 2011a,b). Market orientation is considered as the central element of management philosophy (Deshpandé & Farley, 1999). A company is “market oriented” if information on the all-important customers and buying influences permeates every corporate function, so that strategic and tactical decisions are made interfunctionally and interdivisionally, and these well-coordinated decisions are executed with a sense of commitment (Shapiro, 1988). Narver and Slater (1990) offer a cultural perspective and define market orientation as “the organization culture that most effectively and efficiently creates the necessary behaviors for the creation of superior value for buyers and, thus, continuous superior performance for the business” (p. 21). They identify three behavioral components: (1) customer orientation, which involves understanding target buyers now and over time in order to create superior value for them (customers); (2) competitor orientation, which includes acquiring information on existing and potential competitors, such as their short-term strengths and weaknesses and long term capabilities; and (3) inter-functional coordination, which is the coordinated utilization of company's resources to create superior value for target customers. Continuous innovation is implicit in each of these components (Narver & Slater, 1999). Hult et al. (2003) view these dimensions as a market orientation which thus become part of an organization's cultural competitiveness. Despite the fact that substantial efforts have been made to examine the effect of market orientation on business performance in different countries and industries, the results are rather confusing. For example, while a large body of the above literature suggests there is a positive significant direct effect of market orientation on performance, some scholars (Bhuian, 1997; Caruana, Ramaseshan, & Ewing, 1999; Diamantopoulos & Hart, 1993) find no significant relation between these constructs. Matsuno, Mentzer, and Rentz (2005) stress “the definition” along with “the measurement and development” of market orientation construct have made this confusion. Moreover, previous studies such as Chelariu, Ouattarra, and Dadzie (2002), Santos and Escanciano (2002), Tajeddini (2013) state that there is a serious lack of attention at the practice side of market orientation.

In an attempt to improve existing measures of market orientation, Deng and Dart (1994) include profit orientation to this list. In addition, Porter (1980, 1985) argues that there are two basic sources of competitive advantage, firstly in differentiation that derives from customer, competitor, or innovation-oriented behaviors, and secondly a cost advantage based on the internal orientation or culture of organizations. From a strategic perspective, Olson, Slater, and Hult (2005) distinguish four behaviors in ‘customer, competitor, innovation, and internal/cost-orientations that can lead to a position of competitive advantage, if they are engaged simultaneously. A strong market orientation, when coupled with a culture that emphasizes entrepreneurship and innovativeness, promotes organizational learning (Slater & Narver, 1995). Prior work (e.g., Cooper & Kleinschmidt, 1995a,b) indicates substantially how the individual market orientation relates to innovativeness; for example, customer orientation may be central in linking other orientations to innovativeness (cf. Narver & Slater, 1990). Woodside (2005: 276) argues that “innovation projects may stimulate such team creation and interfunctional coordination; interfunctional coordination may serve as an impetus to innovativeness because increases in communications and team work are likely to generate new ideas and technology explorations”. When controlling for various organizational cultures, such as market, adhocracy, clan, and hierarchy, Deshpandé et al. (1993) found that customer orientation and innovativeness are key determinants for firm performance. Tajeddini, Trueman, and Larsen (2006) found that market orientation has a significant and positive effect on innovativeness.

Finally, Kohli and Jaworski (1990) take a behavioral perspective on market orientation, using market intelligence rather than customer focus as the central element because it is a much wider concept because it includes “consideration of exogenous market factors that affect customer needs and preferences and current as well as future needs of customers” (Kohli & Jaworski, 1990: 3). They suggest the three core themes of customer focus, coordinated marketing and profitability. Their configuration is consistent with Narver and Slater's (1990) conceptualization of a unidimensional construct with three behavioral components. In fact, most authors adopt either the definition of Kohli and Jaworski (1990) or that of Narver and Slater (1990). This research adopts the latter because it is more relevant to the focus of this study. Central to the organization's market orientation is the fundamental value it places on customer orientation. This determines how likely the organization will be to encourage and support innovativeness in the firm's culture (Han, Kim, & Srivastava, 1998; Hurley & Hult, 1998). Accordingly, organizations whose cultures emphasize innovation will tend to pay more attention to market orientation in the Swiss watch industry. Thus,H2

Higher levels of market orientation are associated with higher levels of innovativeness measured by: (a) customer orientation; (b) competition orientation; (c) inter-functional coordination.

2.3Entrepreneurship and innovativenessCorporate entrepreneurship focuses on experimentation involving innovativeness, risk-taking and proactiveness (Tajeddini & Trueman, 2008, 2012; Slater & Narver, 2000; Smart & Conant, 1994). Miller (1983) suggests that entrepreneurial firm is the “one that engages in product–market innovation, undertakes somewhat risky ventures, and is first to come up with ‘proactive’ innovations, beating competitors to the punch” (p. 780). Significant number of scholars have recognized the importance of entrepreneurial activities within existing organizations (Dess et al., 2003; Hult et al., 2003; Adonisi, 2003). In this regard, entrepreneurship refers to the ability of the firm to continually renew, innovate, and constructively take risks in its markets and areas of operation (Miller, 1983; Naman & Slevin, 1993; Tajeddini & Mueller, 2012). Entrepreneurship is identified as a critical organizational process that contributes to firm survival and performance (e.g., Barringer & Bluedorn, 1999; Hitt, Ireland, Camp, & Sexton, 2001; Miller, 1983), and as a major source of new jobs and employment growth as we embark on the twenty-first century (Soloman, 1989). Despite the fact that Schumpeter (1942) was one of the first scholars to put emphasis on the importance of innovation in the entrepreneurial process, the term entrepreneurial orientation was defined by Miller in 1983 entailing three intercorrelated dimensions: proactiveness, innovativeness and risk-taking. This concept, however, was developed further by Covin and Slevin in 1989 and refined by Lumpkin and Dess (1996). Entrepreneurial orientation can be observed as entailing aspects of new entry and especially how new entry is undertaken (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996), and combining existing resources in new ways to develop and commercialize new products, move into new markets, and/or service new customers (Hitt et al., 2001).

The traditional conception of entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial activity has traditionally been conceived as a one-time act that creates a new product or service or even an entirely new business – an act that challenges or “creatively destructs” existing products, services, and market relationships (Bygrave & Hofer, 1991; Schumpeter, 1934). Today, however, entrepreneurship is more likely to be viewed as a process, rooted in an organization's culture, rather than as an event (Hult et al., 2003). The entrepreneurial firm is generally distinguished by the creation of new businesses and the revival of existing businesses (Naman & Slevin, 1993; Slater & Narver, 1995), the ability of the firm to continually renew, initiate change, rapidly react to change flexibly and adroitly, innovate, as well as constructively take risks in its markets and areas of operation (Miller, 1983; Naman & Slevin, 1993). The process itself includes the set of activities necessary to identify an opportunity, define a business concept, assess the needed resources, acquire those resources, and manage and harvest the venture (Morris, Schindehutte, & LaForge, 2001).

Moreover, entrepreneurship interacts with other organizational factors to produce business results as opposed to driving performance independently (Hult, Ketchen, & Nichols, 2002; Hult et al., 2004). Miller and Friesen (1983) have supplied evidence that, under turbulent conditions, successful firms demonstrated more adaptability, flexibility, and higher levels of innovation and entrepreneurship than their less successful counterparts in the same industries did. Morris and Calantone (1991) found a strong perceived need among purchasing executives for more innovation and entrepreneurship within the purchasing function. Hult et al. (2003) found that among cultural competitiveness variables, entrepreneurship represents the most influential and proactive means of developing a market-based culture. However, they concluded that the role of entrepreneurship differs depending on the organizational type (i.e., large and young organizations achieve strong performance by focusing directly on entrepreneurship. In other organizational types, entrepreneurship has an indirect effect on performance). Within the framework of cultural competitiveness, this study focuses on the notion that entrepreneurship, as one of four market-based elements affects innovativeness.H3

Higher levels of entrepreneurial orientation are associated with higher levels of innovativeness.

2.4Learning orientation and innovativenessIn order for organizations to maintain a competitive edge, they must be capable of continuous learning (Senge, 1990). Huber (1991) states that learning occurs in an organization “if through its processing of information, the range of its [organization's] potential behaviors is changed” (p. 89). In an organizational perspective, while Senge (1990) defines organizational learning as “the continual expansion of the organization's capacity to create its future” (p. 89), Shrivastava (1981) observes the learning organization as “the process by which the organizational knowledge base is developed and shaped” (p. 15). Over the course of time, the concept was evolved and Dodgson (1993) defines the learning organization concept as “the way firms build, supplement, and organize knowledge and routines around their activities and within their culture and adapt and develop organizational efficiency by improving the use of the broad skill of their workforces” (p. 377), and Garvin (1993) elaborates as “the skill of creating, acquiring, and transferring knowledge, and of modifying its behavior to reflect new knowledge and insights” (p. 51).

Furthermore, there has been increasing research over the past few years that has focused on the processes and outcomes of organizational learning (Baker & Sinkula, 1999; Day, 1991; Garvin, 1993; Moorman, 1995; Sinkula, Baker, & Noordewier, 1997; Tajeddini, 2011a,b). In particular in the marketing literature, the organizational learning has received considerable attention (e.g., Hult et al., 2003; Hult et al., 2004; Hult, 2002; Kandemir & Hult, 2004; Sinkula, 1994; Slater & Narver, 1995; Tajeddini, 2010). This surge is attributed to the influence of learning orientation combined with other capabilities such as market orientation, innovativeness and entrepreneurship on the creation and maintenance of competitive advantage (e.g., Day, 1991; Henri, 2006; Hult et al., 2003; Hult et al., 2004; Hurley & Hult, 1998; Kandemir & Hult, 2004; Slater & Narver, 1995). More specifically, in the marketing science, the introductions of marketing scholars (e.g., Sinkula, 1994; Slater & Narver, 1995) of the organizational learning construct to marketing represent an important shift in this stream of research. Although it is theorized that market orientation is narrow in scope and contributes to adaptive learning (Narver & Slater, 1994), a learning orientation expands an organization's view and serves as an antecedents to innovativeness, which reflects new behaviors prescribed by the market orientation constructs (Hurley & Hult, 1998). In their empirical research, Slater and Narver (1995) find that market orientation only enhances performance when it is combined with a learning orientation. They further concluded that the “market-driven” business is well positioned to anticipate the developing needs of customers and to respond to them through the addition of innovative products and services (Slater & Narver, 1995). These scholars argue that this ability gives the market-driven business an advantage in the speed and effectiveness of its response to opportunities and threats (Slater & Narver, 1995). Thus, they conclude, “a market orientation is inherently a learning orientation” (Slater & Narver, 1995: 67). In focusing on learning orientation as a cultural construct, Huber's (1991) definition emphasizes cognition to distinguish learning orientation from innovativeness. Thus,H4

Higher levels of learning orientation are associated with higher levels of innovativeness.

2.5Swiss watch firmsIn the late 1960s, Switzerland, a country of nature and precision technologies, well-known for its watch-making excellence for over 100 years dominated the world in watch making. As a matter of fact, the Swiss who were state-of-the-art in watch design, with 90,000 employees working in 1600 firms in the Swiss watch industry (Assink, 2006; Barker, 1989; English, 1999; Lodato, 2006; Tajeddini, 2007), dominated the market for watch-making with 65% of the world market share and over 80% of the profits (Barker, 1989). Yet, this industry failed to realize the dynamics of market orientation to identify and anticipate the unexpressed and latent needs of the customers. Perhaps nobody could imagine that a battery-powered quartz watch, with digital readout and no moving parts, would be the future in watches. Despite the fact that a Swiss research organization invented the quartz technology, the Swiss watch manufacturers discarded it and believed that it could never be the watch of the future (Sabaratnam, 1996). As a consequence their market share of the world watch market significantly plummeted from 65% to 18% (Lodato, 2006), and they lost 46,000 jobs in the 1970s as consumers shifted from mechanical Swiss watches to electronic watches manufactured in the USA and Japan (Sabaratnam, 1996; Serrin, 1982; Tajeddini & Mueller, 2009). However, in the 1990s, when some firms such as Swatch reoriented the industry toward the future and introduced the highly innovative, low-priced, high-quality quartz watch (the Swatch), the Swiss once again achieved world leadership (Schlegelmilch, Diamantopoulos, & Kreuz, 2003). Equally, the introduction of the quartz watch, invented by the Swiss themselves, changed the paradigm of watches (English, 1999) and the Swatch watch based on quartz technology became the world's number-one watch producer within the shortest possible time (Assink, 2006; Paap & Katz, 2004; Tushman, 1997).

In an attempt to accommodate the numerous environmental variables that may affect innovativeness and its influential antecedents, this research investigates the Swiss watch industry because it reflects Europe's historical strength in innovation (Kim & Mauborgne, 1997) and is one of the “strategic pillars” identified by Swiss academics that improves manufacturing performance in the country, and like most industries, it faces substantial environmental turbulence from an increased international competition (Tajeddini et al., 2006). A number of scholars assert the recent success of the Swiss watch manufacturing firms is rooted in its innovativeness (e.g., Barrett, 2000; Royston, 2004; Shuster, 2005), while some others emphasize on the history and decline of this industry arguing that these firms failed to anticipate major changes and the need to innovate (e.g., Kandampully & Duddy, 1999; Ullmann, 1991). Some Swiss companies such as Swatch reoriented the industry toward the future and introduced the highly innovative, low-priced, high-quality quartz watch (the Swatch) (Kim & Mauborgne, 1997) through which the Swiss once again achieved world leadership (Tajeddini, 2009). Therefore, based on prior research, we have developed a model showing the possible links among the relevant constructs with a number of hypotheses to test them in the context of Swiss watch manufacturing firms.

3MethodologyTo examine effectively the relationships between various orientations in a cross-sectional survey, we chose a single industry setting. This approach enables us to consider different orientations and their consequence in the same competitive environment (Noble, Sinha, & Kumar, 2002). Conducting research on a single industry for competitiveness studies has been frequently used in prior research (cf. Celucha, Kasouf, & Peruvemba, 2002; Chen & Hambrick, 1995; Dertouzous, Lester, & Solow, 1989; Gopalakrishnan & Damanpour, 2000; Han et al., 1998; Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Tuominena, Rajalab, & Möller, 2004). Celucha et al. (2002) believe that single industry studies can be very valuable because they reduce the variation present when observations of many industries are made in the same study.

In order to obtain the best insight for theory development, case studies are less useful when the objective of the research is theory testing (Lukas, Tan, & Hult, 2001). Therefore, we relied on quantitative analysis of data from a relatively large sample of Swiss watch firms and their subsidiaries (n=768) registered on the list of the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry (FH). The data collection is divided into several stages: First, once a draft of the questionnaire had been designed, two pretests were conducted to assess the face and content validity of the measurement items in order to insure that members of the marketing managers could understand the measurement scales used in the study. The first questionnaire draft containing the measurement properties was given to a total of seven academics to share their comments and suggestions. Second, after completing the initial pretest, input was conducted with fifteen marketing executives, representing a selection of SBUs of the corporation to make sure that all the questions were relevant from the point of practice. English was used for all the questionnaires since the respondents agreed in our electronic contacts to receive an original version.

By using a cross-sectional survey, the revised questionnaire was mailed twice to all target firms (n=768) in two separate waves in order to improve the response rate to the marketing executives along with preaddressed postage-paid envelopes and a covering letter explaining the purpose of the study and the confidentiality of responses. It has been suggested that survey research at the strategic business units (SBUs) level is the most appropriate method to study the influence of cultural competitiveness on organizational performance (e.g., Deshpandé & Webster, 1989; Hult, Ketchen, & Reus, 2001). Strategic business units (SBUs) were targeted to develop a comprehensive understanding of a broad range of culture and strategy elements and their effect on innovativeness (Hult et al., 2004). The marketing executives were used as key informants in assessing all the constructs described above, an approach applied in numerous studies (e.g., Han et al., 1998; Moorman & Miner, 1997; Narver, Slater, & Tietje, 1998). We followed Huber and Power's (Huber & Power, 1985) guidelines on how to get quality data from single informants.

The extrapolation procedure of Armstrong and Overton (1977) was used to compare early and late responding firms on the mean values of study variables. For comparison purposes, the total sample was split into two groups; those received before the second wave of mailing and those received after the second wave. 146 responses were early (2 weeks prior to the cut-off time) and 92 were late. We then compared these groups in terms of the mean responses on each variable, the demographic profile [using chi-square tests] and the mean values of all the remaining study variables [using t-tests], between early and late respondents, we found no significant differences [at the 0.05 level], leading us to conclude that nonresponse bias was not a likely threat.

The operationalization of the explanatory constructs (market orientation, learning organization, and entrepreneurial orientation) as well as the innovativeness and business performance measures involving the development of scales is discussed. All purified measures were five-point Likert scales anchored by “strongly disagree” and “strongly agree” and drawn from previous research and carefully align with the conceptual aspects of each construct. To measure market orientation, the MKTOR scale of Narver and Slater (1990) was used because of its emphasis on behavioral components of competitor orientation, customer orientation, and interfunctional coordination. These three dimensions were individually summated and used as indicators of the latent market orientation construct (Hult et al., 2004). Despite some concerns about the appropriateness of the market orientation construct, summated scales have been used in numerous past studies (e.g., Han et al., 1998; Hult et al., 2004). Learning orientation was measured using five items derived from Baker and Sinkula (1999), Sinkula et al. (1997) and Hult (1998). These items were used because of their emphasis on the essence of reflection by the presence of values that influence the propensity of a firm to proactively pursue new knowledge and challenge the status quo. Innovativeness was quantified using the five-item scale frequently used by Hurley and Hult (1998), because of its cultural perspective and also because it incorporates management opinion about the receptivity to new ideas and innovation. The entrepreneurial orientation scale is developed using the works of Naman and Slevin (1993) as well as Covin and Slevin (1988, 1989). The scale items capture a firm's tendencies to boldness and tolerance for risk that lead to new market entry (Naman & Slevin, 1993). Business performance was measured using three measures derived from Matsuno, Mentzer, and Özsomer (2002) and one item from Trueman and Pike (2003), making four items in all. The former, self-reported or “perceptual measures”, of business performance indicators of (1) market share, (2) percentage of new product sales to total sales, (3) ROI and the latter is operational measures, and (4) number of new products developed. According to Hunt and Morgan (1996), Matsuno et al. (2002) argue that these performance variables were measured relative to those of the organization's relevant competition, because market orientation is considered to result in competitive (thus, relative) advantage. Because competitors are the standard of comparison in the performance scale, each outcome item is phrased so that respondents evaluated these aspects of business performance relative to their business unit's primary competitors’ (Conant, Mokwa, & Varadarajan, 1990). Matsuno et al. (2002) note why subjective performance measures can be used. They argue that objective relative performance measures are virtually impossible to obtain at the business unit level, and subjective measures have been shown to be correlated to objective measures of performance. In prior studies (e.g., Jaworski & Kohli, 1993; Narver & Slater, 1990; Slater & Narver, 1994, Tajeddini, 2010), subjective measures have been used.

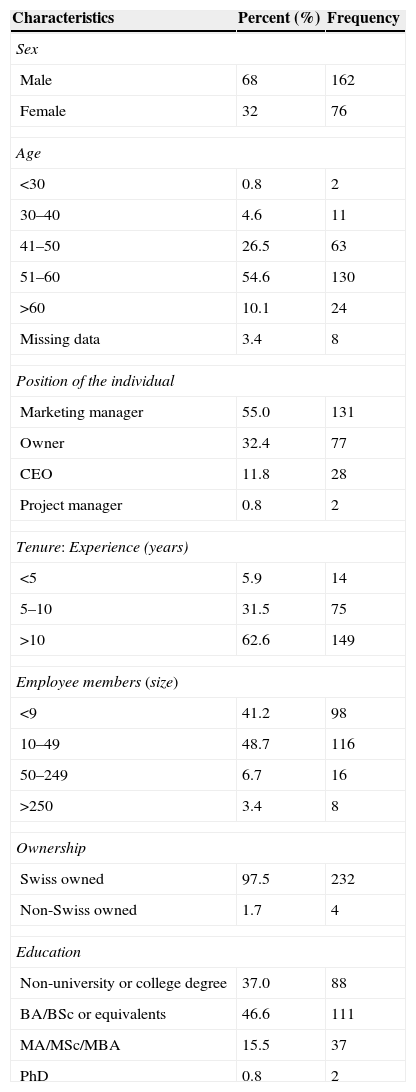

4Analysis and resultsSeven hundred and eighty six (n=786) questionnaires were distributed, 259 were returned (33.33% response rate). However, fifteen surveys were removed because respondents were excused answering the questionnaire due to the firms’ policies. Four surveys were rejected as incomplete and two respondents were not interested in the subject. Their responses, therefore, were withdrawn from the study. This procedure resulted in 238 useful responses or a 30.99% overall response rate, which is similar to the 19–32.9% range reported in similar recent studies (e.g., Auh & Menguc, 2005; Henri, 2006; Hult et al., 2004). Demographic data for the respondents are shown in Table 1. Male and female are nearly even distributed. Male respondents account for 68% (162 males) of the sample, while female respondents account for 32% (76 female).

Profile of respondents (demographic variables).

| Characteristics | Percent (%) | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 68 | 162 |

| Female | 32 | 76 |

| Age | ||

| <30 | 0.8 | 2 |

| 30–40 | 4.6 | 11 |

| 41–50 | 26.5 | 63 |

| 51–60 | 54.6 | 130 |

| >60 | 10.1 | 24 |

| Missing data | 3.4 | 8 |

| Position of the individual | ||

| Marketing manager | 55.0 | 131 |

| Owner | 32.4 | 77 |

| CEO | 11.8 | 28 |

| Project manager | 0.8 | 2 |

| Tenure: Experience (years) | ||

| <5 | 5.9 | 14 |

| 5–10 | 31.5 | 75 |

| >10 | 62.6 | 149 |

| Employee members (size) | ||

| <9 | 41.2 | 98 |

| 10–49 | 48.7 | 116 |

| 50–249 | 6.7 | 16 |

| >250 | 3.4 | 8 |

| Ownership | ||

| Swiss owned | 97.5 | 232 |

| Non-Swiss owned | 1.7 | 4 |

| Education | ||

| Non-university or college degree | 37.0 | 88 |

| BA/BSc or equivalents | 46.6 | 111 |

| MA/MSc/MBA | 15.5 | 37 |

| PhD | 0.8 | 2 |

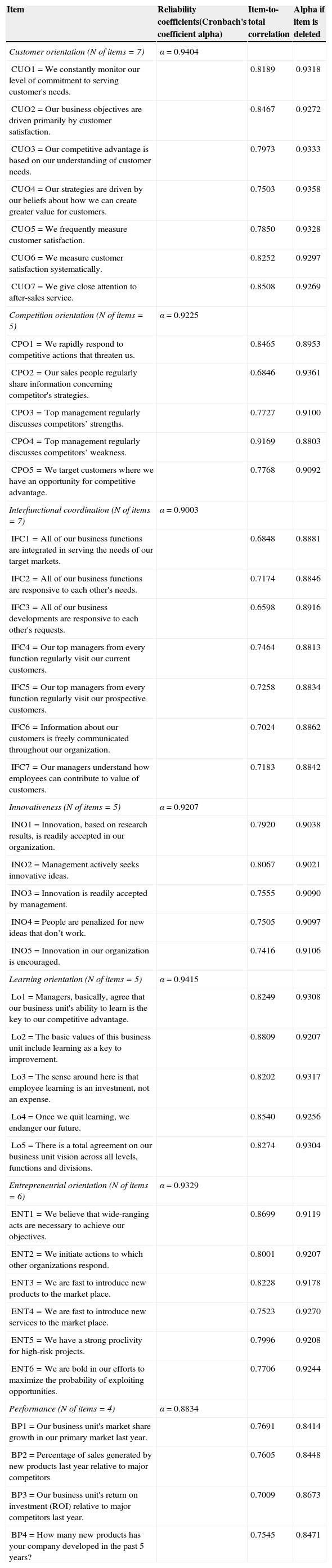

Because we relied on the respondents’ perceptions to measure the constructs of the study, the validity and reliability of these measures were assessed. The reliability analysis uses Cronbach's coefficient alpha (Churchill, 1979) representing the multi-dimensional constructs of innovativeness, customer, competition, entrepreneurial and learning orientation as well as interfunctional coordination and business performance. In Table 2, the overall Cronbach's coefficient alpha showed evidence of internal consistency score for each construct revealing a high level of reliability as, in each case, the value is greater than the suggested cut-off level of 0.7 (Nunnally, 1978). The table also shows the alpha figures on removal of each item. Owing to the small differences between individual item scores and the scale alpha for each construct, the suggestion is that alpha will not be increased by deleting any of the items. This strengthens the case for scale reliability.

Reliability analysis for multi-item scales.

| Item | Reliability coefficients(Cronbach's coefficient alpha) | Item-to-total correlation | Alpha if item is deleted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Customer orientation (N of items=7) | α=0.9404 | ||

| CUO1=We constantly monitor our level of commitment to serving customer's needs. | 0.8189 | 0.9318 | |

| CUO2=Our business objectives are driven primarily by customer satisfaction. | 0.8467 | 0.9272 | |

| CUO3=Our competitive advantage is based on our understanding of customer needs. | 0.7973 | 0.9333 | |

| CUO4=Our strategies are driven by our beliefs about how we can create greater value for customers. | 0.7503 | 0.9358 | |

| CUO5=We frequently measure customer satisfaction. | 0.7850 | 0.9328 | |

| CUO6=We measure customer satisfaction systematically. | 0.8252 | 0.9297 | |

| CUO7=We give close attention to after-sales service. | 0.8508 | 0.9269 | |

| Competition orientation (N of items=5) | α=0.9225 | ||

| CPO1=We rapidly respond to competitive actions that threaten us. | 0.8465 | 0.8953 | |

| CPO2=Our sales people regularly share information concerning competitor's strategies. | 0.6846 | 0.9361 | |

| CPO3=Top management regularly discusses competitors’ strengths. | 0.7727 | 0.9100 | |

| CPO4=Top management regularly discusses competitors’ weakness. | 0.9169 | 0.8803 | |

| CPO5=We target customers where we have an opportunity for competitive advantage. | 0.7768 | 0.9092 | |

| Interfunctional coordination (N of items=7) | α=0.9003 | ||

| IFC1=All of our business functions are integrated in serving the needs of our target markets. | 0.6848 | 0.8881 | |

| IFC2=All of our business functions are responsive to each other's needs. | 0.7174 | 0.8846 | |

| IFC3=All of our business developments are responsive to each other's requests. | 0.6598 | 0.8916 | |

| IFC4=Our top managers from every function regularly visit our current customers. | 0.7464 | 0.8813 | |

| IFC5=Our top managers from every function regularly visit our prospective customers. | 0.7258 | 0.8834 | |

| IFC6=Information about our customers is freely communicated throughout our organization. | 0.7024 | 0.8862 | |

| IFC7=Our managers understand how employees can contribute to value of customers. | 0.7183 | 0.8842 | |

| Innovativeness (N of items=5) | α=0.9207 | ||

| INO1=Innovation, based on research results, is readily accepted in our organization. | 0.7920 | 0.9038 | |

| INO2=Management actively seeks innovative ideas. | 0.8067 | 0.9021 | |

| INO3=Innovation is readily accepted by management. | 0.7555 | 0.9090 | |

| INO4=People are penalized for new ideas that don’t work. | 0.7505 | 0.9097 | |

| INO5=Innovation in our organization is encouraged. | 0.7416 | 0.9106 | |

| Learning orientation (N of items=5) | α=0.9415 | ||

| Lo1=Managers, basically, agree that our business unit's ability to learn is the key to our competitive advantage. | 0.8249 | 0.9308 | |

| Lo2=The basic values of this business unit include learning as a key to improvement. | 0.8809 | 0.9207 | |

| Lo3=The sense around here is that employee learning is an investment, not an expense. | 0.8202 | 0.9317 | |

| Lo4=Once we quit learning, we endanger our future. | 0.8540 | 0.9256 | |

| Lo5=There is a total agreement on our business unit vision across all levels, functions and divisions. | 0.8274 | 0.9304 | |

| Entrepreneurial orientation (N of items=6) | α=0.9329 | ||

| ENT1=We believe that wide-ranging acts are necessary to achieve our objectives. | 0.8699 | 0.9119 | |

| ENT2=We initiate actions to which other organizations respond. | 0.8001 | 0.9207 | |

| ENT3=We are fast to introduce new products to the market place. | 0.8228 | 0.9178 | |

| ENT4=We are fast to introduce new services to the market place. | 0.7523 | 0.9270 | |

| ENT5=We have a strong proclivity for high-risk projects. | 0.7996 | 0.9208 | |

| ENT6=We are bold in our efforts to maximize the probability of exploiting opportunities. | 0.7706 | 0.9244 | |

| Performance (N of items=4) | α=0.8834 | ||

| BP1=Our business unit's market share growth in our primary market last year. | 0.7691 | 0.8414 | |

| BP2=Percentage of sales generated by new products last year relative to major competitors | 0.7605 | 0.8448 | |

| BP3=Our business unit's return on investment (ROI) relative to major competitors last year. | 0.7009 | 0.8673 | |

| BP4=How many new products has your company developed in the past 5 years? | 0.7545 | 0.8471 |

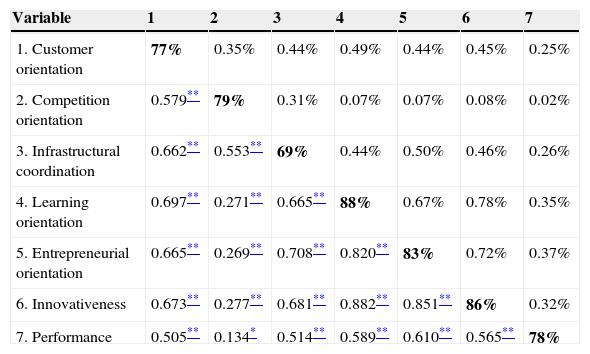

Furthermore, interviews with selected general managers helped ensure that the specified domain of the constructs of interest to the present study were reflected in the measurement scales so representing the content validity of the measures. Discriminant validity within the two-dimensional scales (i.e., customer orientation and learning orientation) was established by calculating the shared variance between the constructs, and verifying that it was lower than the average variances extracted for the individual constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). As shown at Table 3, the shared variances for the scales used in the study ranged from a low of 0.0% to a high of 49%, with the average variances extracted ranging between 69% and 88%, indicating discriminant validity between all constructs.

Intercorrelations and shared of measurers (n=238).a

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Customer orientation | 77% | 0.35% | 0.44% | 0.49% | 0.44% | 0.45% | 0.25% |

| 2. Competition orientation | 0.579** | 79% | 0.31% | 0.07% | 0.07% | 0.08% | 0.02% |

| 3. Infrastructural coordination | 0.662** | 0.553** | 69% | 0.44% | 0.50% | 0.46% | 0.26% |

| 4. Learning orientation | 0.697** | 0.271** | 0.665** | 88% | 0.67% | 0.78% | 0.35% |

| 5. Entrepreneurial orientation | 0.665** | 0.269** | 0.708** | 0.820** | 83% | 0.72% | 0.37% |

| 6. Innovativeness | 0.673** | 0.277** | 0.681** | 0.882** | 0.851** | 86% | 0.32% |

| 7. Performance | 0.505** | 0.134* | 0.514** | 0.589** | 0.610** | 0.565** | 78% |

The correlations are included in the lower triangle of the matrix. For the multiattribute variables, all correlations are significant at the p<0.01 level except the relationship between competition orientation and performance variable (p<0.05). Shared variances are included in the upper triangle of the matrix. Average variances extracted are in the middle of the matrix.

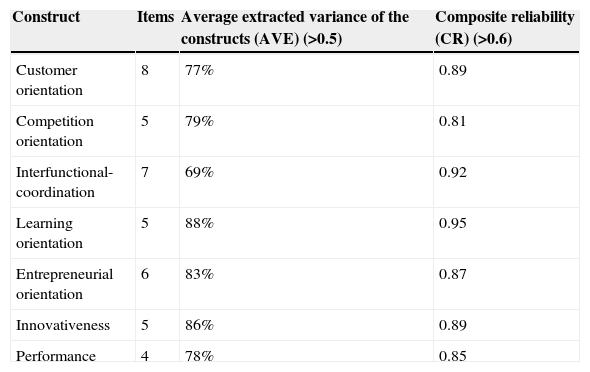

In addition, a series of techniques to test for convergent validity was employed. Composite reliability coefficients (CR) were calculated indicating well above the cut-off of 0.70 recommended by Bagozzi and Yi (1988). The average variance extracted (AVE) values were higher than 0.50 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988) (Table 4). Furthermore, validation of the three orientations leading to innovativeness was established based upon the procedure of Govindarajan (1988). The results show that positive and significant correlation coefficients at the 0.01 level between innovativeness and the three orientations including market orientation (r=0.66), entrepreneurship (r=0.628) and organizational learning (r=0.711). CFA also revealed that all factor loadings were statistically significant (t>2.0) (Gerbing & Anderson, 1988). These findings supported the convergent validity of the scales.

Assessment of reliability for constructs.

| Construct | Items | Average extracted variance of the constructs (AVE) (>0.5) | Composite reliability (CR) (>0.6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Customer orientation | 8 | 77% | 0.89 |

| Competition orientation | 5 | 79% | 0.81 |

| Interfunctional-coordination | 7 | 69% | 0.92 |

| Learning orientation | 5 | 88% | 0.95 |

| Entrepreneurial orientation | 6 | 83% | 0.87 |

| Innovativeness | 5 | 86% | 0.89 |

| Performance | 4 | 78% | 0.85 |

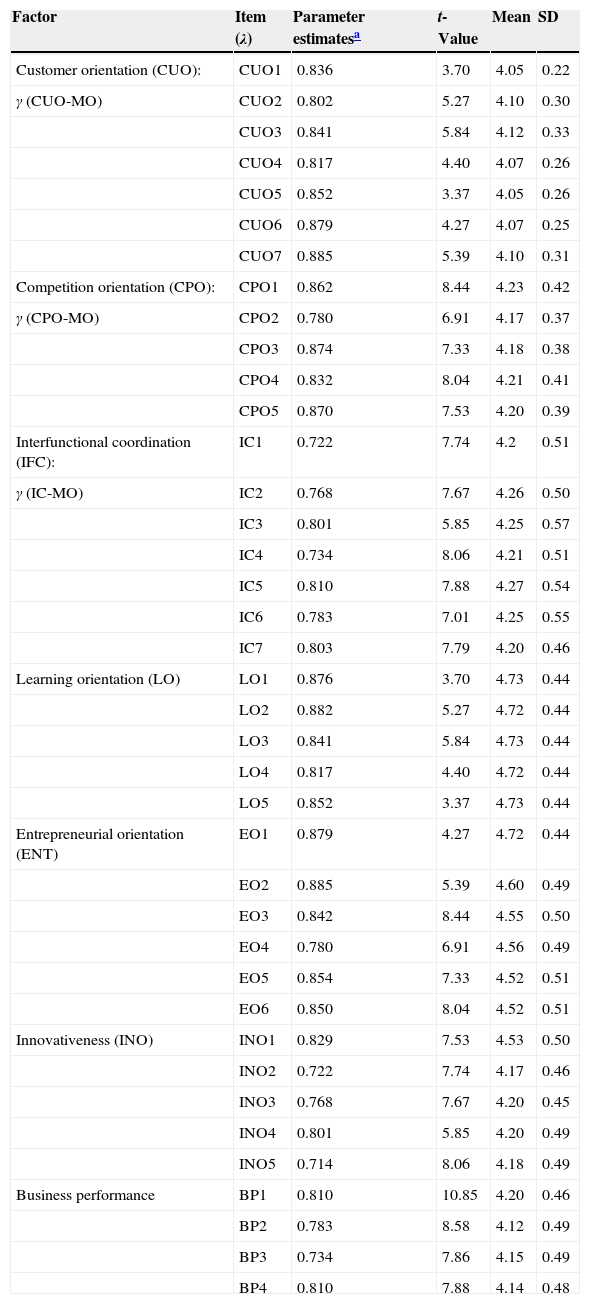

Following data collection, the psychometric properties of the multi-item constructs were evaluated by conducting a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) models using AMOS (Arbuckle & Wothke, 1999) version 5, with the correlation matrices as input into the analyses. The model fits were evaluated using the DELTA2 index (Bollen, 1989), the comparative fit index (CFI) (Bentler, 1990; McDonald & Marsh, 1990), the root mean square error of approximation index (RMSEA) (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999) and TLI (Tucker–Lewis coefficient) (Tucker & Lewis, 1973) which have been shown to be the most stable fit indices in confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling by many authors (e.g., Gerbing & Anderson, 1992; Hu & Bentler, 1999). The root mean square residual index (RMSR), noncentrality parameter (NCP), expected cross-validation index (ECVI), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) and chi-square statistic (χ2) with the corresponding degrees of freedom are included for comparison purposes. Modification index (MI) (<3.84), residual covariation (<|2.58|) and the item's error variance (<0.50) were evaluated to examine possible improvement of the model (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996). The maximum likelihood estimation was adopted. Regarding to the different individual indices, the confirmatory factor model provided a good fit to the data (Delta2=0.986; CFI=0.985; TLI=0.939; RMSEA=0.083; GFI=0.985; NFI=0.977; χ2=13.1, df=5; SRMR (RMR)=0.008; ECVI=0.249; TLI=0.939; AGFI=0.915; RMSEA=0.083) and CMIN/DF (χ2/df ratio)=2.62, supporting the proposed model (Hair, Anderson, Tathan, & Black, 1998).

As Table 5 shows, the parameter estimates (factor loadings) were all significant (t-values ranged from 3.37 to 10.85, p<0.05) and ranged from 0.802 to 0.885 for customer orientation, 0.780–0.874 for competition orientation, 0.722–0.810 for interfunctional coordination, 0.817–0.882 for learning orientation, 0.780–0.885 for entrepreneurial orientation, 0.714–0.829 for innovativeness, 0.734–0.810 for performance.

Summary results for the sample analysis (n=238).

| Factor | Item (λ) | Parameter estimatesa | t-Value | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer orientation (CUO): | CUO1 | 0.836 | 3.70 | 4.05 | 0.22 |

| γ (CUO-MO) | CUO2 | 0.802 | 5.27 | 4.10 | 0.30 |

| CUO3 | 0.841 | 5.84 | 4.12 | 0.33 | |

| CUO4 | 0.817 | 4.40 | 4.07 | 0.26 | |

| CUO5 | 0.852 | 3.37 | 4.05 | 0.26 | |

| CUO6 | 0.879 | 4.27 | 4.07 | 0.25 | |

| CUO7 | 0.885 | 5.39 | 4.10 | 0.31 | |

| Competition orientation (CPO): | CPO1 | 0.862 | 8.44 | 4.23 | 0.42 |

| γ (CPO-MO) | CPO2 | 0.780 | 6.91 | 4.17 | 0.37 |

| CPO3 | 0.874 | 7.33 | 4.18 | 0.38 | |

| CPO4 | 0.832 | 8.04 | 4.21 | 0.41 | |

| CPO5 | 0.870 | 7.53 | 4.20 | 0.39 | |

| Interfunctional coordination (IFC): | IC1 | 0.722 | 7.74 | 4.2 | 0.51 |

| γ (IC-MO) | IC2 | 0.768 | 7.67 | 4.26 | 0.50 |

| IC3 | 0.801 | 5.85 | 4.25 | 0.57 | |

| IC4 | 0.734 | 8.06 | 4.21 | 0.51 | |

| IC5 | 0.810 | 7.88 | 4.27 | 0.54 | |

| IC6 | 0.783 | 7.01 | 4.25 | 0.55 | |

| IC7 | 0.803 | 7.79 | 4.20 | 0.46 | |

| Learning orientation (LO) | LO1 | 0.876 | 3.70 | 4.73 | 0.44 |

| LO2 | 0.882 | 5.27 | 4.72 | 0.44 | |

| LO3 | 0.841 | 5.84 | 4.73 | 0.44 | |

| LO4 | 0.817 | 4.40 | 4.72 | 0.44 | |

| LO5 | 0.852 | 3.37 | 4.73 | 0.44 | |

| Entrepreneurial orientation (ENT) | EO1 | 0.879 | 4.27 | 4.72 | 0.44 |

| EO2 | 0.885 | 5.39 | 4.60 | 0.49 | |

| EO3 | 0.842 | 8.44 | 4.55 | 0.50 | |

| EO4 | 0.780 | 6.91 | 4.56 | 0.49 | |

| EO5 | 0.854 | 7.33 | 4.52 | 0.51 | |

| EO6 | 0.850 | 8.04 | 4.52 | 0.51 | |

| Innovativeness (INO) | INO1 | 0.829 | 7.53 | 4.53 | 0.50 |

| INO2 | 0.722 | 7.74 | 4.17 | 0.46 | |

| INO3 | 0.768 | 7.67 | 4.20 | 0.45 | |

| INO4 | 0.801 | 5.85 | 4.20 | 0.49 | |

| INO5 | 0.714 | 8.06 | 4.18 | 0.49 | |

| Business performance | BP1 | 0.810 | 10.85 | 4.20 | 0.46 |

| BP2 | 0.783 | 8.58 | 4.12 | 0.49 | |

| BP3 | 0.734 | 7.86 | 4.15 | 0.49 | |

| BP4 | 0.810 | 7.88 | 4.14 | 0.48 |

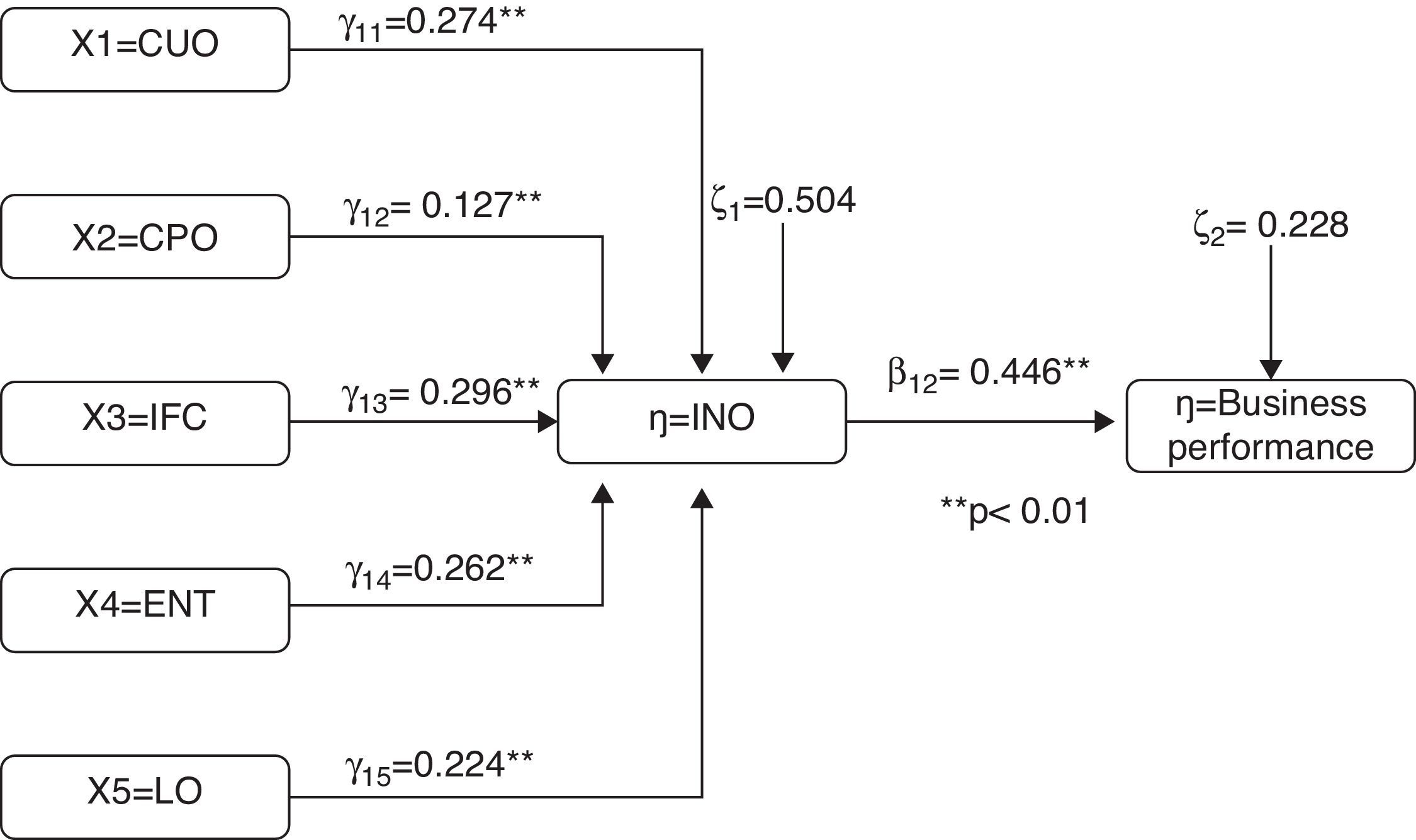

A structural equation modeling (SEM) methodology was employed to test the hypotheses, the relationships depicted in the estimated hypotheses and shown in Fig. 1, using the AMOS program. The technique chosen was maximum likelihood (robust), given the non-normality of some of the measures. Estimating the structural model produced a significant chi-square statistic (χ2=13.1, p=0.02). The structural model explains 38.0%, 12.8%, 40.0%, 19.9%, 12.9% and 44.6% respectively, as measured by the R2 value, of the variation in customer orientation, competition orientation, interfunctional coordination, learning orientation and entrepreneurial orientation providing additional support for the structural model.

The significant path coefficient among five organizational variables. INO=γ11 (CUO)+γ12 (CPO)+γ13 (IFC)+γ14 (ENT)+γ15 (LO)+ζ1. Business performance=β12 (INO)+ζ2; where INO=innovativeness; CUO=customer orientation; CPO=competition orientation; IFC=infrastructure coordination; ENT=entrepreneurial orientation; LO=learning orientation; Business performance=performance (average of the dimensions); γ and β are parameters.

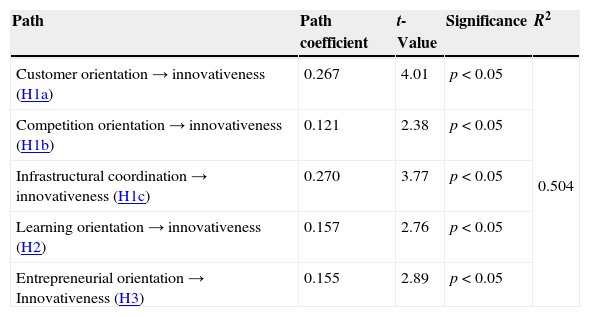

Standardized parameter estimates and t-values for the model are shown in Table 6, and the results support all hypotheses. The findings indicate that innovativeness is influenced by all three market orientation dimensions, supporting H1a, H1b and H1c. Innovative firms are more likely to satisfy the customers (path coefficient=0.2670, t-value=4.01, p<0.05), keep ahead of the competition (path coefficient=0.121, t-value=2.38, p<0.05), and coordinate the utilization of company resources in creating superior value for its customers (path coefficient=0.270, t-value=3.77, p<0.05). Results support H2, indicating higher levels of learning orientation are associated with higher levels of innovativeness (path coefficient=0.157, t-value=2.76, p<0.05). Furthermore, in support of H3, higher levels of entrepreneurial orientation is associated with higher levels of innovativeness (path coefficient=0.155, t-value=2.89, p<0.05).

Path, path coefficient, t-value, probability and r-squared.

| Path | Path coefficient | t-Value | Significance | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer orientation→innovativeness (H1a) | 0.267 | 4.01 | p<0.05 | 0.504 |

| Competition orientation→innovativeness (H1b) | 0.121 | 2.38 | p<0.05 | |

| Infrastructural coordination→innovativeness (H1c) | 0.270 | 3.77 | p<0.05 | |

| Learning orientation→innovativeness (H2) | 0.157 | 2.76 | p<0.05 | |

| Entrepreneurial orientation→Innovativeness (H3) | 0.155 | 2.89 | p<0.05 |

Fit indices: Delta2=0.986; CFI=0.985; TLI=0.939; RMSEA=0.083; GFI=0.985; NFI=0.977; χ52=13.1; RMR=0.008; ECVI=0.249; TLI=0.939; AGFI=0.915; RMSEA=0.083 (p=0.02).

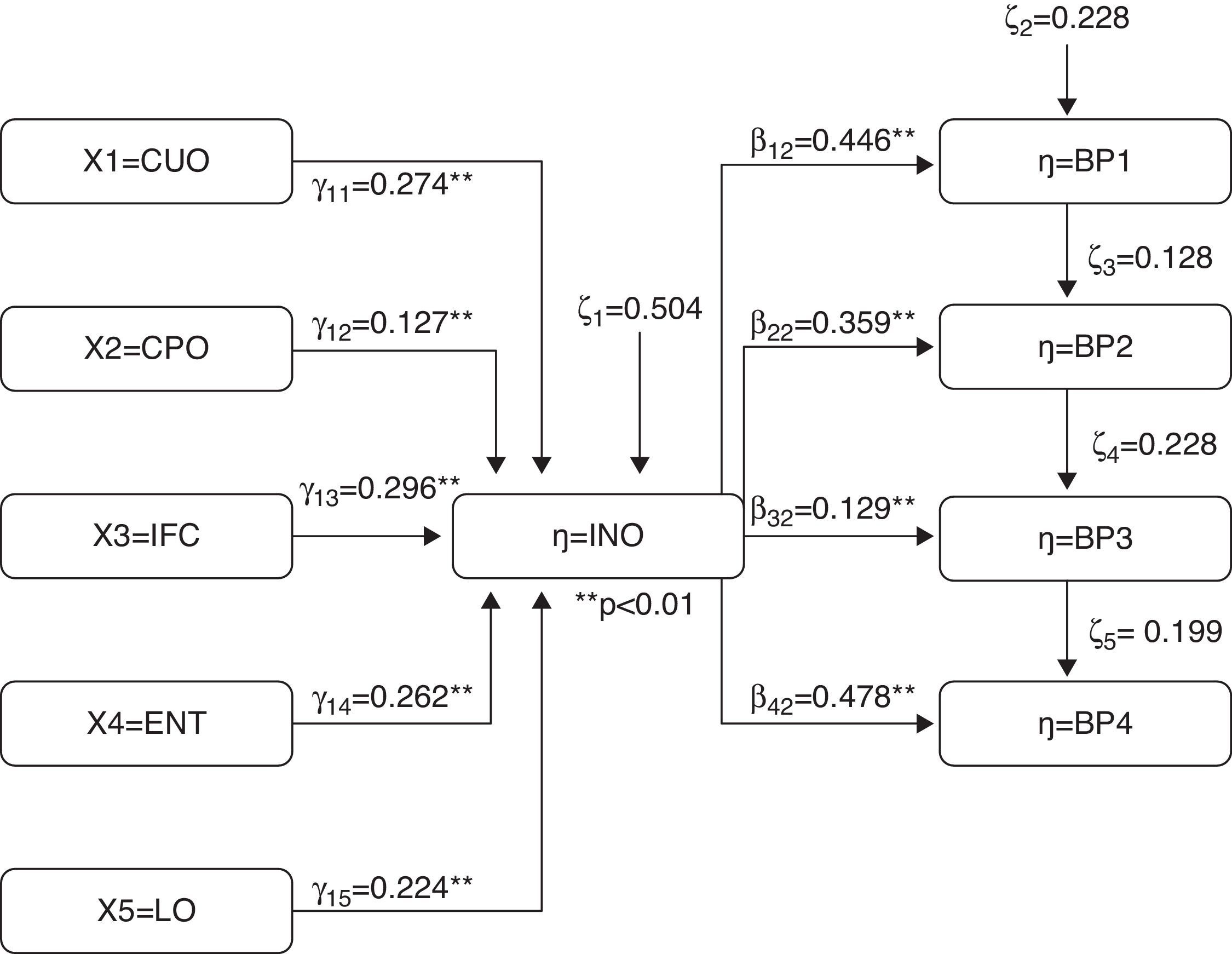

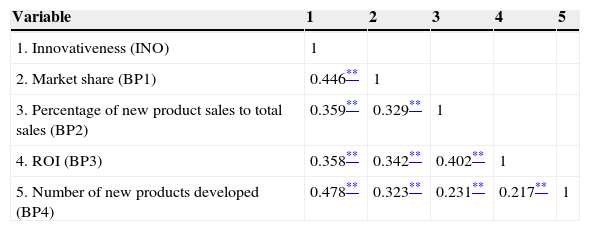

Noteworthy, innovativeness was significantly correlated with all four dimensions of business performance namely, market share (r=0.446, p<0.01), percentage of new product sales to total sales (r=0.359, p<0.01), ROI (r=0.358, p<0.01) and number of new products developed (r=0.478, p<0.01).

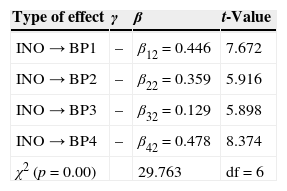

To further exploring the relationship between innovativeness and the four dimensions of business performance, Table 7 exhibits the beta, gamma, and t-value of the relationship variables. As it shows the innovativeness has a positive and significant effete on different dimensions of business performance. The fit statistics indicates a reasonable model fit (AGFI=0.880; RMR=0.014; CFI=0.881; GFI=0.952 TLI=0.801; IFI (Delta2)=0.883; RMSEA=0.129; CMIN/DF=4.960).

Correlation among variables of innovativeness and performance dimensions.

SEM results, as reported in Table 8, indicated that high innovative organizations tend to have a better market share (t=7.67, p<0.00) – supporting Hypothesis 1a, report more percentage of new product sales to total sales (t=5.91, p<0.00) – supporting Hypothesis 1b, provide higher levels of ROI (t=5.89, p<0.00) – supporting Hypothesis 1c, and achieve higher level number of new products developed (t=8.37, p<0.00) – supporting Hypothesis 1d (Fig. 2).

Beta and gamma coefficient and associated t-value.

| Type of effect | γ | β | t-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| INO→BP1 | – | β12=0.446 | 7.672 |

| INO→BP2 | – | β22=0.359 | 5.916 |

| INO→BP3 | – | β32=0.129 | 5.898 |

| INO→BP4 | – | β42=0.478 | 8.374 |

| χ2 (p=0.00) | 29.763 | df=6 |

AGFI=0.880; RMR=0.014; CFI=0.881; GFI=0.952; TLI=0.801; IFI (Delta2)=0.883; RMSEA=0.129; CMIN/DF=4.960.

The significant path coefficient among five organizational variables. INO=γ11 (CUO)+γ12 (CPO)+γ13 (IFC)+γ14 (ENT)+γ15 (LO)+ζ1. BP1=β12 (INO)+ζ2. BP2=β22 (INO)+ζ3. BP3=β32 (INO)+ζ4. BP4=β42 (INO)+ζ5; where INO=innovativeness; CUO=customer orientation; CPO=competition orientation; IFC=infrastructure coordination; ENT=entrepreneurial orientation; LO=learning orientation; BP1–4=performance; γ and β are parameters.

Overall, results find evidence supporting all four hypotheses regarding the dimensions of business performance in the current study. That is, managers in general perceived that more innovative organizations benefit from a greater level of market share, higher levels of percentage of new product sales to total sales, greater levels of ROI and finally higher levels of number of new products developed than less innovative ones. Also, it can be concluded that those more innovative organizations tend to perform better in the market than those who are not innovative.

8Discussion and conclusionThis study attempts to evaluate the intervening role of the innovativeness variable linking market, learning, and entrepreneurial orientations to business performance. The current paper addresses the impact of key antecedents to innovativeness in a comprehensive, empirically verified model and examines how three different types of organizational cultural competitiveness can lead to greater innovativeness. Understanding relationships among these variables that underlie strategic decisions is critical to understanding effective strategic implementation. Exploring cognitive relationships contributes toward understanding the “black box” that links market and learning orientation coupled with entrepreneurship and ultimately firm performance (Celucha et al., 2002). We thereby filled a significant gap in understanding innovativeness, the nature of relationships between innovativeness and key variables that drive it. We hypothesized that this relationship would be more pronounced under certain contextual and environmental conditions. Specifically, the survey data from the Swiss watch manufacturing firms were utilized to examine quantitatively the extent to which the organizations have adopted market orientation, market-based organizational learning, and corporate entrepreneurship and their impact on innovativeness and subsequent effect on performance. The findings are consistent with prior research (e.g., Henri, 2006; Hult et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2003; Sandvik & Sandvik, 2003; Tajeddini et al., 2006), but provide a new insight by exploring the impact of cultural competitiveness factors upon innovativeness in a world-class manufacturing industry in order to observe the results in a similar environmental condition. Accordingly, organizations whose cultures emphasize innovation, when resources are available, will tend to implement more innovations and develop competitive advantage (Hurley & Hult, 1998). Results reveal that current Swiss watch firms are comparatively innovative, learning-oriented, market-oriented, and with an emphasis on entrepreneurship as well. More importantly, it is found that higher levels of customer orientation, competitor orientation and inter-functional coordination lead these firms to be more innovative. Furthermore, the results provide strong support for the positive effect of the innovativeness to achieve and stimulate a higher level of organizational performance. These findings are consistent with Kara et al. (2005) (p. 105) who believe that “conventional marketing wisdom holds that a market orientation provides a company with a better understanding of its customers, competitors, and environment, which subsequently leads to superior firm performance”. Similarly, Deshpandé et al. (1993) suggest that in order to better understand the functioning of customer orientation, the concept should be related to innovativeness of an organization's culture. In addition, higher market and learning orientations and entrepreneurship relate to overlapping yet distinct capability portfolios. Consistent with extant literature, all these three orientations appear to be related positively to business performance. For instance, this study confirms prior research (e.g., Slater & Narver, 1995) that organizational learning is an important tool for organizations’ efforts to overcome challenges, enhance success, and support innovativeness in the firm's culture (Han et al., 1998; Hult et al., 2004; Hurley & Hult, 1998; Tajeddini, 2010). Further, it is consistent with Hult et al. (2004) which state that entrepreneurial orientation embodies strategies and actions that the firm may undertake in order to actualize corporate orientations and goals and it has a significant effect on innovativeness. More specifically, those firms with higher level of innovativeness tend to have more market share, higher percentage of new product sales to total sales, greater ROI and a higher number of new products developed. The results might provide an initial benchmark of organizational culture and strategy attributes apparent in conjunction with certain contingencies in an organization's operating environment. Several contributions to various research streams are noteworthy. First, the findings may highlight the degree of importance of a more integrated and compositional approach to the study of the effect of innovativeness and antecedent orientations. This approach may be more realistic than previous approaches of examining bivariate relationships between each of the constructs separately. Next, since previous studies have confirmed that there is a positive relationship between innovativeness and business performance in a turbulent environment (Hult et al., 2004), it can be argued that the empirical findings of this research can imply that innovative activities may also be generally important to the success of the industrial firm in a world-class manufacturing industry with the same environment.

9Practical implicationsThe paper provides strategic insights and practical thinking that have influenced some of the world's leading organizations. The paper has practical implications for managers involved in unifying focus for the efforts and projects of individuals as it shows the importance of an organization focusing on strategic emerging capabilities such as innovativeness, market orientation, entrepreneurial orientation and learning orientation, thereby leading to superior performance. First our managers can be advised to improve the innovativeness of their businesses in their efforts to attain superior business performance (market share, increases levels of percentage of new product sales to total sales, ROI, and number of new products developed). This research shows that it is important to source ideas from a wide base outside as well as inside the organization, so that customers, suppliers, competitors, as well as employees all have a potential role to play in terms of innovativeness. Senior managers should recognize the value of informal networks for accessing and evaluating new ideas, as well as the formal processes within the organization. Consequently, it can help contribute to achieving sustainable competitive advantage. Second, senior managers and owners are advised to put emphasis on constant commitment to learning and establishing a culture of learning in their organizations. They should also recognize the importance of learning climate and network organization as an organizational structure relying on multiparty co-operative relationships among people, flexible communications, leadership and professional involvement, as well as displaying a clear understanding of how these factors affect company performance. Third, numerous management theorists have observed that the nature of entrepreneurship as a key determinant of renewal activities enhancing a firm's ability to compete and take risks. From empirical evidence, we found that managers must foster an entrepreneurial spirit and culture if they intend to improve their innovativeness. In this regard, managers in different levels of responsibilities are advised to stimulate entrepreneurial spirit and thinking among their employees. Forth, this empirical research shows that managers and owners are encouraged to be engaged in increased customer-oriented activities (i.e., quick, respectful and committed responses) which may lead the business to satisfy customers and eventually enhance performance. This can be done through being close to ambassadors (i.e., retailers and distributors, and shops), but not to be too close to fail to develop competencies to innovate, design, and introduce new products to the market earlier than their rivals. Additionally, in order to achieve a competitive advantage, senior managers should constantly be aware of competitors’ actions to move faster. Finally, this research also indicates that managers should observe market orientation as a phenomenon that occurs between and across several functional areas of the firm, and at different levels. They are advised to continue this practice irrespective of the intensity of global competition and uncertainty in the business environment.

10Limitations and further researchAs with any research project, there are limitations which should be discussed. First, the study is limited to Swiss watch firms. Generalizing the results to other industries and countries may not be appropriate. Further research is needed on the SMEs and large firms in other countries to assess whether the structure uncovered is universal. Second, all data were collected in a cross sectional manner, and therefore, all we can conclude is that the role variables and their posited consequences are related at one point in time. Bollen (1989) stated that an acknowledged weakness of cross-sectional design is that causality is much harder to infer because of temporal priority, one pre-requisite for inferring causality is not present. Using a longitudinal study may help to identify the direction of causality between variables. Fourth, the use of control variables and environmental variables may not exclude other factors influencing the results (Tajeddini, 2013, 2015). Finally, the study is based on self-report data incurring the possibility of common method bias. However, our tests of common method variance do not find it to be a significant problem in this study. We also use multiple assessments including Cronbach alphas, composite reliability, to support the accuracy of the data and the results. Future studies might use objective measures for firm performance to strengthen the research design. Three major priorities are proposed for future research. It would be useful to replicate this study and repeat this model testing approach using a completely new sample. Interesting comparisons could then be undertaken by using an identical model for a developing country, different industries and then comparing the estimated structural parameters. Second, more antecedents’ variables could be incorporated into the model and finally using a longitudinal study, may help to identify the direction of causality between variables.