In a hypercompetitive world, the affirmation of virtuosity has faced considerable resistance. However, ethics and morality, voices rise up in defense of a virtuous leadership, capable to give significantly positive contributions to organizations and their employees. Starting from this premise, this research aims to analyze, based on perceptions of the followers, the impact of virtuous leadership in organizational commitment, as well as the contribution of the latter on individual performance. Sustained on a quantitative methodology, we inquired, in a first phase, 113 employees from organizations located in the Portuguese territory, in order to ascertain which virtues are most valued in a leader. The data for hypothesis testing were collected using a battery of tests with 351 employees. The results suggest that the employees’ perceptions, around three dimensions of leadership virtuosity (values-based leadership, perseverance and maturity), contribute to organizational commitment, especially in its affective and normative dimensions, and the latter, in turn, is able to positively influence individual performance.

Profuse literature has demonstrated that leadership is one of the most important factors for the performance of an organization, influencing, dynamically, on individual and organizational interaction (Obiwuru, Okwu, Akpa, & Nwankwere, 2011), so that any reflection around the phenomenon of leadership can provide a capital contribution to any organization.

Concomitantly, the organizational manifestations of virtuosity and its consequences remain underdeveloped theoretically and empirically (Rego & Cunha, 2010). In today's hypercompetitive world, the virtuosity easily falls for the latest plan on the scale of organizational priorities, rarely acknowledging, “the enormous value of the practice of the virtues for the effective exercise of leadership” (Rego & Cunha, 2011, p. 23). However, management practices devoid of virtues can generate traumatic effects on the reputation and performance of leaders, led and organization as a whole (Rego & Cunha, 2011).

Finally, given the competitive advantage of commitment, this study may represent a relevant contribution to scientific knowledge, relating this phenomenon to leadership.

Based on the framework described, which supports the relevance of this study, we seek to meet two basic objectives: (1) understand the extent to which an established leadership virtues may favor the organizational commitment; (2) analyze the impact of organizational commitment; on the performance of employees.

2The virtuosity in leadershipThe word virtue derived from the Latin virtus meaning “virtue” or “excellence” (Rego, Victória, Magalhães, Ribeiro, & Cunha, 2013). The virtue or virtues (as there are many and varied) are rules of moral character that motivate and guide behavior toward the end of an ethical order.

At the organizational level, and according to Cameron, Bright and Caza (2004) a virtuous organization enables and supports virtuous activities – good habits, desires and actions – from its members. It incorporates the actions of individuals, collective activities, cultural attributes and other processes that allow the dissemination and perpetuation of virtuousness of the organization. These organizations not only promote virtuous relationships among its members, but also instigate it in people's management: when defining its strategy, worry about being good and doing good; when they develop a process of downsizing, they do it with care and compassion; when facing crises, they do it with maturity, wisdom and tolerance; and even facing difficulties, they can flourish (Cameron & Caza, 2002).

Rego and Cunha (2010), anchoring in several studies (Cameron, 2003; Cameron et al., 2004; Wilson, Dejoy, Vandenberg, Richardson, & McGrath, 2004), highlight that virtuosity contributes to organizational health, manifested in intentional, systematic and collaborative efforts that maximize productivity and well-being of employees, in a supportive organizational environment, where there are accessible and equitable opportunities for progression and where easily identify the meaning of work.

Concerning the relationship between virtuousness and organizational effectiveness, Cameron et al. (2004) conducted a survey involving 18 organizations and showed that organizational virtuousness – analyzed at the level of trust, integrity, forgiveness, compassion and optimism – relates positively and significantly to organizational performance, particularly in terms of innovation, customer retention, turnover, quality and profitability. The authors based the explanation of these results in those they consider to be the key attributes of virtuosity: amplifying effects – that can instigate an escalation of positivity – and buffering effects – capable of protecting the organization from negative intrusions.

Rego and Cunha (2011) argue that the leader can fully contribute to the success of the teams and organizations “since endowed with virtues and psychological forces such as courage, humility, perseverance, integrity, prudence, curiosity, vitality, confidence and passion” (p. 29). Although the existence of these virtues is not by itself sufficient for business success, these increases, in the medium and long term, the odds of being effective leaders and achieve better results. At the same time that increases the performance of organizations, the virtuous leaders can be happier, elevate the happiness of the led, the progress of the organization and society. On the other hand, the exercise of leadership lacking virtues can generate traumatic effects on leaders, followers and organization as a whole.

3The organizational commitmentAllen and Meyer (1996) define organizational commitment as the psychological bond that characterizes the connection between the individual and the organization, reducing the chances of his departure.

Although initially the organizational commitment has been approached as a one-dimensional construct (Mowday et al., 1982, cited in Nascimento, Lopes, & Salgueiro, 2008), several other studies point to its multidimensionality, including the most widespread (Allen & Meyer, 1990, 2000; Meyer, 1997; Meyer & Allen, 1991), which covers three dimensions: affective, normative and instrumental. The affective dimension refers to the identification, involvement and emotional attachment of the individual to the organization; the normative relates with the sense of obligation or moral duty of staying in the organization; and the instrumental with the maintenance of the connection of the employee to the organizations considering costs associated with leaving the company. Common to the three dimensions – affective, normative and instrumental – it is the fact that all connect the individual to the organization; divergent is the nature of each of these connections. When affectively committed, the employee remains in the organization because he wants to, when normatively committed, remains because he has to, and when committed instrumentally, remains because he needs (Allen & Meyer, 1990).

Rego and Souto (2004) reported that among the antecedents that contribute to reinforce the normative commitment and, especially, the emotional, we can highlight: the affective ties, the transformational leadership, the support of the company, leader and colleagues, the performance feedback, the receptivity of management to suggestions from employees, the challenge inherent to the role, the perceptions of justice and the perception that the organization is guided by humanist and visionary values, that it is fair and socially responsible.

Regarding the impacts of commitment, although all three forms of commitment relate negatively to turnover intentions, these manifest themselves differently in other relevant conduct in the employment context, such as assiduity, performance and organizational citizenship behaviors. More specifically, it is expected to observe a stronger positive relationship between these behaviors and affective commitment, followed by normative commitment; in contrast, it is expected instrumental commitment to be independent, or negatively related with these desirable work behaviors (Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, 2002). Of the three types of commitment, affective commitment entails the biggest advantage for the organization, insofar as the emotional connection to the organization will result, most likely, in a more powerful contribution toward organizational objectives, in a lower turnover, lower absenteeism, higher performance and major incidence of organizational citizenship behaviors. The normative commitment also powers positive contributions to the organization, however, the underlay of feelings of obligation, does not instigate the same enthusiasm and commitment as the affective commitment type. Finally, the instrumental involvement leads to performances that tend not to exceed the minimum requirements (Rego & Souto, 2004). Research shows that it is between affective commitment and a positive impact on attendance, punctuality, citizenship behaviors and performance that registers higher correlation results. It is more likely to record intensely vigorous efforts when there is an emotional involvement of employees in the organization than when they feel obliged or simply need to remain in it (Cunha, Rego, Cunha, & Cabral-Cardoso, 2007). Engaged and committed employees, willing to adopt spontaneous, innovative and citizenship behaviors represent an asset for organizational success. Ultimately, the performance of the organization correlates with the level of involvement of its employees and their teams (Sezões, 2012). Committed employees “are more satisfied and motivated and are thus more productive and loyal” (Palma, Lopes, & Bancaleiro 2011, pp. 44–45). It is assumed, therefore, that a greater commitment of employees results in a greater chance of remaining in the organization and engages in the performance of their duties and the pursuit of organizational objectives (Cunha et al., 2007).

Our principal question has “To what extent the virtuous leadership contributes to the enhancement of organizational commitment, and this, in turn, affects individual performance?” With this research we intend therefore reach out to two fundamental objectives: (1) To understand the extent to which leadership based on virtues can promote organizational commitment and (2) analyze the impact of organizational commitment in the performance of subordinates. To this end, we are dedicated to test the following theoretical hypotheses:H1

It is expected that the virtues of the leaders can predict a higher organizational commitment. More specifically it is expected that the higher the virtuous leadership, the higher rates of the organizational commitment.

H2It is expected that the organizational commitment be positively related to a better performance. That is, the greater the organizational commitment level the better the performance of workers.

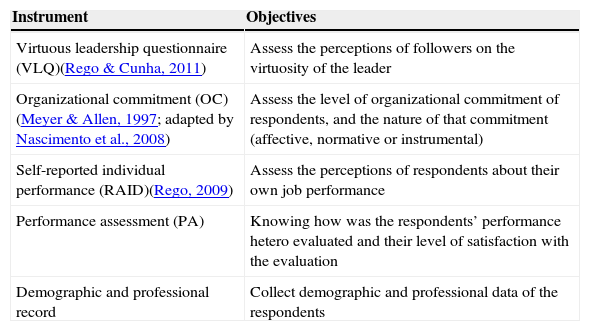

4Methodological optionsA convenience sample of 351 subordinated workers was inquired in various companies operating in Portugal. The distribution of the instrument was conducted by email. The administration of the instrument was direct (through Survey Gizmo platform) and the responses were received electronically (Table 1).

List of instruments used in the study, authors and objectives.

| Instrument | Objectives |

|---|---|

| Virtuous leadership questionnaire (VLQ)(Rego & Cunha, 2011) | Assess the perceptions of followers on the virtuosity of the leader |

| Organizational commitment (OC)(Meyer & Allen, 1997; adapted by Nascimento et al., 2008) | Assess the level of organizational commitment of respondents, and the nature of that commitment (affective, normative or instrumental) |

| Self-reported individual performance (RAID)(Rego, 2009) | Assess the perceptions of respondents about their own job performance |

| Performance assessment (PA) | Knowing how was the respondents’ performance hetero evaluated and their level of satisfaction with the evaluation |

| Demographic and professional record | Collect demographic and professional data of the respondents |

Regarding the fidelity of the global scale (QLV_Total), the value found for internal consistency is high (Cronbach's alpha=.89). The Centered Leadership Values and Perseverance subscales have high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=.97 and .85, respectively), and the Maturity subscale has a reasonable internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=.63). The subscales of affective organizational commitment and organizational commitment normative had a good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=.86 and .87, respectively), while the organizational commitment Instrumental subscale has a reasonable internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=.73). The fidelity of the values (Total DIAR), if we consider this measure as one-dimensional, is good (Cronbach's alpha=.77). The subscales of the instrument also showed good internal consistency (DIAR_I Cronbach's alpha=.768; and DIAR_E: Cronbach's alpha=.891).

We conclude, therefore, that these instruments retain its psychometric properties in the sample studied here, can be used with confidence in hypothesis testing.

The sample comprised 67.1% of females and 32.9% of males. The majority (66.1%) of participants had up to 39 years of age and 78.8% of respondents had higher education. The most represented sectors of activity were health (20.6%) and education (14.5%). The majority of (51.9%) participants held positions at private institutions, 45.5% of which are over 250 workers. The seniority in the organization of the majority of respondents (57.6%) is less than 10 years. The same applies to seniority in the function, in most of the cases also lower than 10 years (65.3%) (Table 2).

Demographic characteristics of total sample (N=351).

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 103 | 32.9 |

| Female | 210 | 67.1 |

| Age (years) | ||

| <20 | 0 | 0 |

| 20–29 | 67 | 21.4 |

| 30–39 | 140 | 44.7 |

| 40–49 | 67 | 21.4 |

| 50–59 | 36 | 11.5 |

| ≥60 | 3 | 1.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 90 | 28.8 |

| Married/union | 204 | 65.2 |

| Divorced/separate | 18 | 5.8 |

| Widower | 1 | .3 |

| Education | ||

| 4th grade | 1 | .3 |

| 6th grade | 1 | .3 |

| Junior High School | 8 | 2.6 |

| High school | 56 | 17.9 |

| Bachelor | 11 | 3.5 |

| Grade | 171 | 54.6 |

| Master | 57 | 18.2 |

| PhD | 7 | 2.2 |

| PosDOC | 1 | .3 |

In line with our first goal, our Theoretical Hypothesis 1 predicted that the virtuous leadership was a significant predictor of organizational commitment. A correlational study demonstrated that virtuous leadership correlates significantly and positively with organizational commitment, particularly creating a strong relationship between all dimensions of virtuous leadership and organizational commitment total, affective and normative. The relationship between the dimensions of the virtuous leadership and organizational commitment instrumental exists, but is less expressive. Between the dimension Maturity and Instrumental organizational commitment it does not appear to be any significant correlation (Table 3).

Results of Pearson correlation coefficients between VL and OC (N=351).

| Organizational commitmentTotal | Organizational commitmentAffective | Organizational commitmentNormative | Organizational commitmentInstrumental | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtuous leadership total | .512** | .538** | .506** | .167** |

| Centered on values | .497** | .520** | .493** | .163** |

| Perseverance | .434** | .457** | .415** | .142* |

| Maturity | .278** | .302** | .272** | .085 |

Level of significance * for p<.05 / ** for p<.01.

Predictive analytics corroborates the correlational study, showing that the virtuous leadership is associated with an increased organizational commitment. Effectively, in this sample, when leaders are perceived as virtuous, professionals manifest more commitment. So we can conclude that the perceptions of virtuousness in leadership predict the organizational commitment, especially the affective and normative, having little or no (in the case of Maturity) influence on the instrumental (Table 4).

Simple linear regression of QLV in OC total (N=320).

| Variable | β | t | g.l. | p | F | r | r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtuous leadership total | .512 | 11.972 | 318 | .000** | 113.257 | .512 | .263 |

| Centered on values | .497 | 10.207 | 318 | .000** | 104.178 | .497 | .247 |

| Perseverance | .434 | 8.599 | 318 | .000** | 73.942 | .434 | .189 |

| Maturity | .278 | 5.162 | 318 | .000** | 26.643 | .278 | .077 |

Level of significance * for p<.05 / ** for p<.01.

The results of simple linear regression as the dependent variable in the total organizational commitment are shown in Table 4. We can say that all the variables of virtuous leadership contribute significantly to predict the total organizational commitment. Leadership virtuous total explains 26.3% of the variance; centered on values explains 24.7% of variance; Perseverance explains 18.9% of the variance; and Maturity explains 7.7% of the variance. ANOVA results are highly significant for all predictor variables: virtuous leadership total [F (1,318)=113,257, p<.001]; centered on values [F (1,318)=104,178, p<.001]; Perseverance [F (1,318)=73,942, p<.001]; Maturity [F (1,318)= 26,643, p<.001].

Analyzing the individual contribution of each variable of virtuous leadership for organizational commitment Affective, we found that virtuous leadership total explains 29% of the variance – ANOVA result is highly significant [F (1,319)=130.235, p<.001]. Centered on values variable explains 27% of the variance. ANOVA results also highly significant [F (1,319)=118,225, p<.001]. The Perseverance explains 20.9% the variance. ANOVA results is highly significant [F (1,319)=84,137, p<.001]. The Maturity explains 9.1% and the variance – ANOVA is significant [F (1,319)=31.920, p<.001] (Table 5).

Simple linear regression of QLV in OC affective (n=321).

| Variable | β | t | g.l. | p | F | r | r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtuous leadership total | .538 | 11.412 | 319 | .000** | 130.235 | .538 | .290 |

| Centered on values | .520 | 10.873 | 319 | .000** | 118.225 | .520 | .270 |

| Perseverance | .457 | 9.173 | 319 | .000** | 84.137 | .457 | .209 |

| Maturity | .302 | 5.650 | 319 | .000** | 31.920 | .302 | .091 |

Level of significance * for p<.05 / ** for p<.01.

Regarding the contribution of each variable to the explained variance of the dependent variable, the virtuous leadership total contributes 25.6%, the values-centered leadership with 24.3%, Perseverance with 17.3% and maturity with 7.4%. The ANOVA results are highly significant: virtuous leadership total [F (1,319)=110 009, p<.001]; values centered leadership [F (1,319)=102,620, p<.001]; Perseverance [F (1,319)= 66 557, p<.001]; Maturity [F (1,319)=25.483, p<.001] (Table 6).

Simple linear regression of QLV in OC normative (N=321).

| Variable | β | t | g.l. | p | F | r | r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtuous leadership total | .506 | 10.489 | 319 | .000** | 110.009 | .506 | .256 |

| Centered on values | .493 | 10.130 | 319 | .000** | 102.620 | .493 | .243 |

| Perseverance | .415 | 8.158 | 319 | .000** | 66.557 | .415 | .173 |

| Maturity | .272 | 5.048 | 319 | .000** | 25.483 | .272 | .074 |

Level of significance * for p<.05 / ** for p<.01.

Finally, a simple linear regression taking as dependent variable the organizational commitment instrumental, it was established that the variables total virtuous leadership, values and leadership focused on Perseverance positively predict the dependent variable in the analysis (Table 7). Although this model, the predictor contribution is smaller than the above explored. The results continue to show statistical significance that enables confirmation of their predictability. Whilst the percentages of explained variance does not exceed 2.8%, the ANOVA results remain significant, particularly in the virtuous leadership total [F (1,318)=9.150, p<.01] and focused on leadership values concerns [F (1,318)=8.661, p<.01].

Simple linear regression of VL in OC instrumental (n=320).

| Variable | β | t | g.l. | p | F | r | r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtuous leadership total | .167 | 3.025 | 318 | .003** | 9.150 | .167 | .028 |

| Centered on values | .163 | 2.943 | 318 | .003** | 8.661 | .163 | .027 |

| Perseverance | .142 | 2.561 | 318 | .011* | 6.559 | .142 | .020 |

Level of significance * for p<.05 / ** for p<.01.

Another relationship under analysis in this study is the relationship between organizational commitment and individual performance. For this, we have built Theoretical Hypothesis 2, which predicted that the organizational commitment would positively relate to a better performance and more positive results in terms of their assessment. The correlational study showed that the organizational commitment total predicts significantly and positively the self-reported individual performance (DIAR) total and self-reported individual performance intra-organizational.

Meaning that the more committed the professionals are – on global, affective and normatively terms – the more positive will be their assessment of their own performance (PA), whether it is considered in global terms or exclusively on internal context. Simultaneously, the stronger is organizational commitment (total, affective and normative), the higher is the grade of agreement with the Rating Obtained Last Performance Assessment (Table 8).

Results of Pearson correlation coefficients between OC, DIAR and PA (N=318).

| Variable | DIAR_Total | DIAR_Intra_organizational | DIAR_Extra_organizational | Last Assesment AD | Degree of agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO_ Total | .171** | .279** | −.012 | −.018 | .191** |

| CO_Affective | .198** | .314** | −.004 | −.014 | .198** |

| CO_Normative | .132* | .228** | −.023 | .042 | .245** |

| CO_Instrumental | .077 | .123 | −.002 | −.082 | .007 |

Level of significance * for p<.05 / ** for p<.01.

The results obtained confirm that the more committed the individual is with his organization (especially if this commitment results from the establishment of emotional bonds, but also if derives from a sense of duty and loyalty), the better is his performance level (Tables 9–11). The organizational commitment total and its dimensions affective and normative positively predict the dependent variable. The organizational commitment total explains 2.9% of the observed variance; the organizational commitment affective explains 3.9% and organizational commitment normative explained 1.8%.

Simple linear regression of OC in degree of compliance with the classification obtained last performance evaluation (n=228).

| Variable | β | t | g.l. | p | F | r | r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO_Total | .191 | 2.933 | 228 | .004** | 8.602 | .191 | .036 |

| CO_Affective | .198 | 3.057 | 228 | .003** | 9.345 | .198 | .039 |

| CO_Normative | .245 | 3.816 | 228 | .000** | 14.562 | .245 | .060 |

Level of significance * for p<.05 / ** for p<.01.

The results presented in Table 10 indicate that 7.8% of the variance explained by the total organizational commitment is 9.8% of the variance for affective organizational commitment; and 5.2% by normative organizational commitment. All results are highly significant in the ANOVA: total to organizational commitment [F (1,316)=26,773, p<.001]; for organizational commitment affective [F (1,316)=34,478 p<.001]; and for organizational commitment normative [F (1,316)=17.361, p<.001].

Finally, and as can be seen in Table 11, the results of simple linear regression considering the Degree of Compliance with the Classification Obtained Last Performance Evaluation, reveal that the variables organizational commitment total, organizational commitment affective and organizational commitment normative are significant predictors of this dependent variable. The organizational commitment total explains 3.6% of the variance; organizational commitment affective explained 3.9% and organizational commitment normative explained 6%. The results of the ANOVA test are revealed to be significant in all dimensions: organizational commitment total [F (1,228)=8.602, p<.01]; organizational commitment affective [F (1,228)=9,345, p<.01] and organizational commitment normative [F (1,228)=14,562, p<.000].

A greater commitment translates into a stronger effort to remain in the organization, with a heavier commitment, involvement and effort to the exercise of its functions and the pursuit of organizational goals.

6Discussion and conclusionsWith this study we seek to strengthen appeal to the practice of virtues in organizational context, particularly in leadership positions, showing the impact of VL in organizational commitment and, consequently, on individual performance. The empirical research conducted using a quantitative methodology allowed us to conclude that a more virtuous leadership predicts a higher organizational commitment – mainly in their affective and normative aspects – and that a higher organizational commitment – except for the instrumental – predicts a better performance. Perceptions of organizational virtuousness could influence affective commitment. It is likely that individuals who perceived their organizations as virtuous develop a stronger sense of perceived organizational support (Rego, Ribeiro, & Cunha, 2010).

Gouldner (1960) presents the norm of reciprocity as a trigger for a stronger emotional response. Perceptions of organizational virtuosity and corresponding perceptions of being valued and considered by the organization can also encourage the incorporation of organizational membership in the self-identity of the employee (Lilius et al., 2008). The recognition of organizational virtuosity can create a sense of obligation to repay through normative commitment (Allen & Meyer, 1996).

Thun and Kelloway, a study published in 2011, concluded that a leader's virtues like humanity, wisdom and temperance, provoked a set of consequences with potential positive impacts on organizational performance, including, for the case highlight the enhancement of affective commitment. Thus, in line with the literature, we can conclude the confirmation of our Theoretical Hypothesis 1. The virtuous leadership predicts organizational commitment, as the leader's virtuosity manifested in values (such as justice, integrity or honesty), enhances a positive environment, welfare, trust and cooperation can strengthen the emotional ties the individual to the organization (affective organizational commitment); their loyalty and sense of duty to act accordingly – trying to give as much as you receive – (organizational commitment normative). Commitment that stems from the fact that possibly another organization may not benefit from the same “benefits” trying hard to avoid the costs that a hypothetical exit could lead them (instrumental organizational commitment).

The correlational study provided the clues to test Hypothesis 2, indicating the existence of statistically significant relationships between organizational commitment, performance assessment, and the degree of agreement with performance assessment. The predictive study clarified the nature of the relationships suggested by the correlational study, confirming that, as we predicted when elaborating Hypothesis 2, the organizational commitment positively influences the individual performance. Indeed, it was proven that organizational commitment predicts significantly and positively individual performance. The more committed they are professionals – in global, affective and normative terms – will be more positive in their assessment of their own performance, whether considered in global terms or exclusively on internal context. Simultaneously, the stronger the organizational commitment (total, affective and normative) more pronounced the Degree of Compliance with the Classification Obtained Last Performance Evaluation.

The absence of any relationship between organizational commitment and individual performance (Extra_organizational), as well as compliance with the Classification Obtained Last Performance Assessment may be related: (1) in the case of perceptions on performance, with the difficulty that respondents in comparing oneself with professionals from other organizations for not knowing the parameters of their performance; (2) in the case of classification obtained in the last performance assessment, with the fact that about half of the population surveyed work in public organizations where the performance evaluation system is constrained by the quota system.

Apart from the contribution that these findings pose for deeper understanding of the concept of virtuous leadership and its direct impact on organizational commitment and indirect in the professional performance, of the relations evidenced here, necessarily emerge a set of recommendations for Human Resource Management (HRM). In first place, it is recommended that organizations are particularly cautious in recruitment and selection of their leaders, ensuring that the values and principles of the potential leader are grounded in respect for a set of virtues such as social intelligence, honesty, humility, justice and perseverance. Also in performance management, leadership virtuosity can be enhanced if included in the content of leadership training and/or development of leadership skills using coaching programs.

Performance assessment is another of Human Resources Management practices that may represent a valuable resource in promoting virtuous leadership if the virtues of the leader, as reflected in their attitudes and behaviors, integrate the set of evaluation criteria. Simultaneously, considering that effective leadership is not exclusive of the leader, but it is also affected for the followers and the context, the virtuosity is promoted also by replication of these practices among led and through the organizational culture, which should be a culture of sharing, giving and receiving feedback, of attention to the needs of employees. The communication of ethical values of the organization should not be neglected as well as the prevention of unvirtuous conduct, acting to avoid their reoccurrence or perpetuation. HRM must also ensure knowledge of either the levels of virtuosity in leadership and organization as a whole, whether the levels of organizational commitment, considering the results of these studies in the internal definition of the Strategic Plan for Human Resources (People Plan).

Due to the positive impact of the virtuous leadership in organizational commitment and individual performance, and in turn, on the organizational performance, it is desirable that the theme of this research is continuously explored by other research. These will have to face the challenge of seeking to overcome the limitations of this research: to deepen the understanding of the relationships explored here, extending the application of the study to a larger sample size, making possible the generalization of results; to enrich the understanding of the object of study with the consideration of the perspective of the leaders themselves; and, to improve the assessment of the instrument of the leader's virtuosity (VLQ) in order to achieve a factorial structure in line with what we sought to achieve when designing the instrument based on the most relevant virtues in a leader considered ideal (information obtained through the instrument Leadership – Prioritization of the virtues of the leader according to its perceived importance, applied in an exploratory phase). It also would be relevant to explore the direct relationship between virtuous leadership and individual performance and deepen it, through a parallel study with a larger number of followers, the knowledge about the virtues they value most in a leader using the instrument we developed in this research exploratory forays (Leadership – Prioritization of the virtues of the leader according to its perceived importance).