Research suggests that those suspected of sexual offending might be more willing to reveal information about their crimes if interviewers display empathic behaviour. However, the literature concerning investigative empathy is in its infancy, and so as yet is not well understood. This study explores empathy in a sample of real-life interviews conducted by police officers in England with suspected sex offenders. Using qualitative methodology, the presence and type of empathic verbal behaviours displayed was examined. Resulting categories were quantitatively analysed to investigate their occurrence overall, and across interviewer gender. We identified four distinct types of empathy, some of which were used significantly more often than others. Female interviewers displayed more empathic behaviour per se by a considerable margin.

La investigación indica que las personas sospechosas de agresión sexual podrían estar más dispuestas a revelar información sobre sus delitos si los entrevistadores muestran un comportamiento empático. No obstante, los estudios sobre la empatía en la investigación están aún en mantillas, por lo que aún no se entiende bien. Este estudio explora la empatía en una muestra de entrevistas en la vida real realizadas por agentes de policía en Inglaterra con presuntos delincuentes sexuales. Se analizó mediante metodología cualitativa la presencia y el tipo de comportamientos verbales empáticos mostrados. Las categorías obtenidas se analizaron cuantitativamente con el fin de investigar su aparición global y en función del sexo del entrevistador. Se identificaron cuatro tipos diferentes de empatía, algunos de ellos utilizados con más frecuencia que otros. Las entrevistadoras mostraron mayor comportamiento empático per se por un margen considerable.

Interviews conducted by police officers with a person suspected of wrongdoing1 are complex social interactions during which interviewers are tasked with gathering information about a suspect's involvement, or otherwise, in a criminal offence (Bull & Milne, 2004). This type of interview calls on police officers to initiate and manage conversations that include asking personal and searching questions, which suspects are often reticent to answer, while seeking to maximize the disclosure of investigation-relevant information (e.g., Shepherd, 2007; Walsh & Bull, 2012).

Information collected during interviews with suspects is valuable because it underpins the efficacy of the Criminal Justice System (CJS) from the very start of the investigative process through to bringing an offender to justice. Therefore, the manner in which interviews with suspects are managed, particularly how police officers support the disclosure of ‘difficult’ information, is of interest because effective conversation management is a significant determinant of the success of an interview (Shepherd, 2007). By success, we mean the admission of guilt by a perpetrator, or the disclosure of sufficient information to support the CJS to successfully prosecute offenders and/or protect the innocent.

The cornerstone of managing a non-coercive information-gathering interview is co-operation (Shepherd, 2007). One way of scaffolding co-operation is for interviewers to respond verbally to their environment in a sentient manner (here we refer to the combination of what the suspect says, and how s/he acts as the environment). Sentient verbal behaviour includes offering situational understanding from the suspect's perspective (Hodges & Klein, 2001), commonly referred to as empathy. Empathy ‘in the field’, that is, the use of verbal empathy when interviewing suspected sex offenders, is the focus of the current study. Specifically, we examine whether officers are able to demonstrate understanding of a suspect's perspective, communicate that understanding, and recognize and respond to empathic opportunities presented by a suspect during an interview.

The use of empathy can foster the disclosure of information, and research suggests that some offenders may be more likely to admit their crimes when interviewers display empathic, non-judgmental behaviour (e.g., Holmberg & Christianson, 2002; Kebbell, Hurren, & Mazerole, 2006; Oxburgh & Ost, 2011). While admissions of guilt and/or information disclosure are important interview outcomes per se, the unique nature of sexual offences is such that the importance of these outcomes is heightened (Farrell & Taylor, 2000; Hanson, Broom, & Stephenson, 2004). Many sexual offences take place in private settings, and so there are typically no witnesses. Hence, all too often police officers have only the account provided by a complainant to rely on when interviewing the person suspected of having committed the offence (see Gregory & Lees, 2012). Sex offenders may also be less likely to admit guilt and/or disclose information due to perceived shame, public disapproval, or sentence severity (Gudjonsson, 2006; Holmberg & Christianson, 2002; Kebbell et al., 2006). Further, the reporting of sexual offences in England and Wales (and elsewhere) is increasing (in 2012/13 in England & Wales 53,700 sexual offences were reported), yet convictions remain stubbornly low, at around 27% (Home Office, 2011). Accordingly, understanding police officers’ symbolic verbal communication with this particular type of offender, with a view to considering how to improve co-operation, is both important and timely (see also Oxburgh & Dando, 2011).

There exist numerous definitions of empathy, encompassing a broad range of emotional states, all of which are generally conceptualised in the realm of the abstract. However, it is generally agreed that an empathic interaction involves understanding the emotional states of others and communicating some recognition of their emotional state (Schwartz, 2002). The definition of empathy offered by Davis (1983) – a reaction of one individual to the observed experiences of another – was used to guide the current study because the data available for analysis were in the form of audio recordings and verbatim transcripts, and concerns what is being said, and when, rather than the way in which empathic communication is delivered.

The literature on the use of empathy by police officers is in its infancy. Some researchers have recently begun the process of investigating empathy in police interviews, and its impact on the amount of information obtained (Oxburgh, Ost, & Cherryman, 2012; Oxburgh, Ost, Morris, & Cherryman, 2015). However, their findings have been mixed, and as such investigative empathy is not well understood. Also guided by Davis’ (1983) definition, a dichotomous coding technique was employed, whereby empathy was deemed present only if officers continued conversations in which suspects seemed not to be fully expressing their underlying emotions, termed ‘empathic opportunities’. Empathy was deemed absent if officers ignored conversations in which suspects appeared to be expressing underlying emotions they were feeling. Empathy was found not to impact upon the amount of information obtained during interviews, a finding that runs counter to those of others, and to theoretical accounts of empathy and cooperation (e.g., Balconi & Bortolotti, 2013; Holmberg & Christianson, 2002; Kebbell et al., 2006; Rumble, Van Lange, & Parks, 2009).

While the aforementioned work represents an important first step towards understating empathy in an investigative context, empathy is a complex phenomenon, with both cognitive and affective components (Davis, 1983). The former concerns responding appropriately to another's mental state, the latter is the capacity to understand the mental state, or perspective of another. Given the unique characteristics of suspect interview environments, investigative empathy may require alternative dimensions in its articulation: it may be a more complex construct than merely continuing conversations of presumed emotion. As such, the manner in which empathy has previously been operationalised and coded may not have captured its heterogeneous nature, and this may account for the mixed findings.

Interviewer variables are also likely to affect empathic behaviour (e.g., Banissy, Kanai, Walsh, & Rees, 2012; Besel & Yuille, 2010). In particular, there is an abundance of literature to support the existence of gender differences. For example, females have been found to be more empathic than males (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004), with femininity being strongly and positively correlated with empathy (Karniol, Gabay, Ochion, & Harari, 1998), a finding supported by research (Gettman, Ranelli, & Reid, 1996), which suggests gender influences behaviour and responses to others. Previous interviewing research has not yet considered gender, although Oxburgh et al. (2012) did comment that suspects (who were all male) appeared to offer more ‘empathic opportunities’ to female interviewers than to male interviewers.

Despite considerable advancements in interview training for police officers in UK the last 20 years, and a move away from coercive interviewing towards information-gathering in many other countries (e.g., Intelligence Science Board, 2009), training protocols typically contain minimal reference to the use of empathy. Even in the UK, the Achieving Best Evidence document (ABE; Home Office, 2011) contains only one reference to empathy, stating that officers should develop rapport with interviewees by displaying empathy, which is defined as, “showing respect and sympathy for how the witness feels” (p. 199). However, this advice is offered in relation to witnesses only, sympathy and empathy are different concepts (Cuff, Brown, Taylor, & Howat, 2014), no definition of empathy is provided, and moreover guidance is not offered as to how officers might communicate empathy.

Understanding and labelling types of verbal empathy will support the development of a taxonomy of investigative verbal empathy, which in turn will allow researchers to more fully assess whether investigative empathy fosters disclosure of information and, if so, which types of empathy are most effective. Understanding gender effects will further advance our understanding of empathic communication by indicating the importance, or otherwise, of gender for increasing co-operation in police interviews. A taxonomy may also allow police and other agencies with an interest in encouraging the disclosure of information in non-coercive face-to-face interactions to further develop training to support interviewers to understand what empathy is, how to recognise empathic opportunities, and how to communicate empathy effectively.

The research reported here addresses two key research questions concerning police officers’ use of empathy during interviews with suspects of sexual offences against children, namely: (i) what types of empathic behaviours do police interviewers display and (ii) do male and female police interviewers differ in the types of verbal empathy they display and in the occurrence of empathy?

MethodResearch DesignEmploying a mixed methods approach. Research question one was considered using grounded theory and research question two was investigated using inferential statistical analyses to examine the occurrence and frequency of the empathy types that emerged, both overall and as a function of interviewer gender. Grounded theory was well suited for this research because it supports the derivation of analytic categories directly from the data rather than from pre-conceived hypotheses. To date, there exists no pre-existing theory to label and explain specific types of empathic behaviour displayed by police officers during interviews with sex offenders (or indeed any type of offender), and the limited amount of published research has employed a broad operational definition of empathy (see also Oxburgh & Ost, 2011; Oxburgh et al., 2012; Oxburgh et al., 2015). Given that empathy is a complex and multifaceted cognitive and social phenomenon (e.g., Jolliffe & Farrington, 2004; Larden, Melin, Holst, & Langstrom, 2006), grounded theory was employed to label types of empathy in the first instance.

Data Analysis and ProcedureA sample of 36 audio recorded interviews, which had taken place between 2005 and 2012, conducted by 36 police officers employed by two major police forces in England2 were analysed for this research. The interviews were supplied directly to the research team by the police forces following a request from the authors. The inclusion/selection criteria was broad, as follows: i) interviews should be with persons suspected of a sexual offence/sexual offences against children, ii) interviewees should be over the age of 18 years, iii) half of the sample should be conducted by females, and half by males, and iv) all interviews should be conducted under police caution. The police forces supplying the interview data were blind to the research aims and research questions, but had been provided with an overview document outlining the general nature of the research, how the data would be analysed, stored, anonymised, and reported.

Accordingly, the authors were supplied with the 36 interviews, all of which met the inclusion criteria: 18 were conducted by female police officers, 18 by male officers, all with adult males over the age of 18 years who had been arrested on suspicion of sexual offences against children. Additionally, all interviews had been conducted using the PEACE model (PEACE is a mnemonic for the stages of an investigative interview: Planning and preparation, Engage and explain, Account, Closure, and Evaluation (see Clarke, Milne, & Bull, 2011).

First, the audio data were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber (approved by both police forces involved). All transcripts were then passed to three coders who independently (and blind to the gender of the police interviewer) read each transcript one or more times. The focus then shifted to open coding, which involved coders working independently to identify empathic concepts within the text, to saturation (Charmaz, 2006), and developing categories that represented their meaning in terms of properties and dimensions (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Throughout, extensive notes were written to summarise the researchers’ understanding, interpretations, and connections. Working together, using the research notes as a guide (Corbin & Strauss, 2008), categories created in ‘open coding’ were then refined to provide more precise and selective codes for empathy types. Throughout, empathic incidents were compared for similarities, violations, and differences within and between interviews. Although there were some initial disagreements between the three coders about particular categorisations, agreement was reached through a process of critical and constructive debate between coders and the authors.

ResultsInterviewsThe mean duration of the interviews was 129minutes (SD=39minutes, range 36-209minutes). In 30 of the interviews two police officers were present; in the remaining six there was just one interviewer. In the case of joint interviewers, only the primary interviewer's behaviour was coded (the officer who asked the majority of the questions and who led the interview process). In 22 interviews, a legal representative was present throughout. In our sample, all the interviewees denied the sexual offences they were being interviewed about (rape and/or sexual assault of a person under 16 years). However, of the sample, 10 interviewees admitted lesser sexual offences (e.g., viewing pornographic images, committing indecent exposure etc.).

Qualitative Analysis - Grounded TheoryIn the Grounded Theory model, investigative empathy is represented as an overarching concept that encapsulates interviewer behaviours falling within the aforementioned broad definition of empathy provided by Davis (1983). Four distinct types of empathy emerged, which are described and labelled as follows, with representative exemplars.

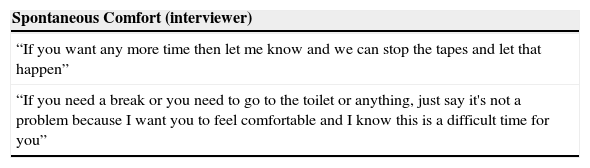

Empathy 1: Spontaneous comfort. Spontaneous comfort occurred without prompting (see Table 1 for examples), that is, it was offered directly by the interviewer without any preceding statement or description from the interviewee from which a police interviewer might infer an underlying emotion (see also Oxburgh & Ost, 2011). Spontaneous comfort was offered in addition to the formal information that is provided to interviewees at the commencement of an interview under caution3. Here, spontaneous comfort included offering the interviewee refreshment and comfort breaks, asking the interviewee if he required additional time with his legal representative and asking if there was anything that could be done to assist the interviewee to feel comfortable.

Representative Examples of Spontaneous Comfort Empathy, Comfort Empathic Opportunities and Comfort Empathic Continuers

| Spontaneous Comfort (interviewer) |

|---|

| “If you want any more time then let me know and we can stop the tapes and let that happen” |

| “If you need a break or you need to go to the toilet or anything, just say it's not a problem because I want you to feel comfortable and I know this is a difficult time for you” |

| Empathic Comfort Opportunity (interviewee) | Empathic Comfort Continuer (interviewer) |

|---|---|

| “This is really hard coz I am having trouble saying stuff” | “Do you think you are able to carry on, or would you like to take a break, just take some time out and get a drink?” |

| “I can’t do this, why should I tell you this stuff, you’re joking, yeah? I can’t” | “You know it's really important you tell me, even though it is hard for you. Would it help if you took a break, then you could talk to… and he can help you decide? Do you want a drink?” |

| “I don’t want to talk about this anymore, it is too upsetting and I have been awake all night” | “I am sorry shall we have a break so that you can compose yourself for a while, maybe get a drink or have something to eat. Things often feel better when we have eaten some food and taken a break and had some refreshment?” |

Empathy 2: Continuer comfort. Continuer comfort examples are displayed in Table 1 (including the preceding statement made by the interviewee). Continuer comfort concerned the same verbal offerings as above (comfort & refreshment breaks, time out, time with legal representative etc.). However, this type of empathy occurred only in response to empathic opportunities concerning the difficulties that the interviewee was experiencing. The interviewer's responses are referred to as empathic opportunity continuers (Oxburgh & Ost, 2011), and on this occasion the continuers concerned comfort (as above). An empathic opportunity precedes a continuer and is described as, “a statement or description from which a police interviewer might infer an underlying emotion that has not been fully expressed by the suspect”, and a continuer occurs where the interviewer “recognizes and reacts to the opportunity in a manner that facilitates the implied emotion or statement” (Oxburgh & Ost, 2011, p. 184).

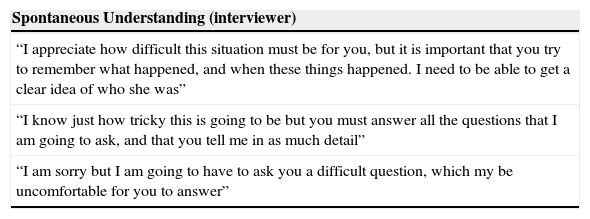

Empathy 3: Spontaneous understanding. Spontaneous understanding occurred when the interviewer spontaneously offered some understanding of the interviewee's situation. As with spontaneous comfort, this was done without any preceding statement or description from the interviewee. For example, acknowledging the difficulty of the interview situation for the interviewee and prefacing questions with empathetic statements (see Table 2).

Representative Examples of Spontaneous Understanding Empathy, Understanding Empathic Opportunities and Understanding Empathic Continuers

| Spontaneous Understanding (interviewer) |

|---|

| “I appreciate how difficult this situation must be for you, but it is important that you try to remember what happened, and when these things happened. I need to be able to get a clear idea of who she was” |

| “I know just how tricky this is going to be but you must answer all the questions that I am going to ask, and that you tell me in as much detail” |

| “I am sorry but I am going to have to ask you a difficult question, which my be uncomfortable for you to answer” |

| Empathic Understanding Opportunity (interviewee) | Empathic Understanding Continuer (interviewer) |

|---|---|

| “What do you want me to say, that I am a useless man and a really **** father and husband - what can I say?” | “I can see that you are upset, can I help you in any way, what can I do to help?” |

| “It was a very hard time, and one that is difficult to talk about” | “You are finding this really difficult aren’t you? Just take your time, we don’t have to rush. I know when I have had to answer difficult questions myself, that it is better to take some deep breaths first” |

| “I just cant answer that, it aint right,its too difficult, you know what I mean” | “I am sorry that you are finding my constant questioning tricky, but as I explained I have to ask you what happened in some detail. Please just take your time, and think for a while before you speak, this might help you to tell me more. I understand how difficult you are finding this”. |

Empathy 4: Continuer understanding. Interviewers also responded to understanding opportunities concerning the difficulties that the interviewee may be experiencing with empathic understanding continuers (see Table 2). The interviewer's responses concerned some understanding of the interviewee's situation, and the difficulties he may be experiencing (as above).

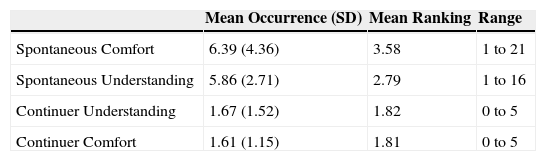

Quantitative Data Analysis - Occurrence of EmpathyFreidman analysis for the occurrence of the four types of empathy (that is, the number of times the four behaviours were displayed) revealed that interviewers (irrespective of gender) used some empathy types significantly more often than others, χ2(3, N=36)=50.11, p < .001 (see Table 3 for mean occurrence, and mean rank order

Mean Overall Occurrence and Rank Order of the Four Types of Empathic Behaviours

| Mean Occurrence (SD) | Mean Ranking | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous Comfort | 6.39 (4.36) | 3.58 | 1 to 21 |

| Spontaneous Understanding | 5.86 (2.71) | 2.79 | 1 to 16 |

| Continuer Understanding | 1.67 (1.52) | 1.82 | 0 to 5 |

| Continuer Comfort | 1.61 (1.15) | 1.81 | 0 to 5 |

Post-hoc analysis with Wilcoxon signed-rank tests revealed that spontaneous comfort occurred significantly more often than spontaneous understanding, Z=-3.44, p=.001, continuer comfort, Z=-4.97, p < .001, and continuer understanding, Z=-4.84, p < .001. Spontaneous comfort occurred significantly more often than both continuer comfort, Z=-4.56, p < .001 and continuer understanding, Z=- 4.16, p < .001. There was no significant difference for the occurrence of the latter two behaviours, p=.978.

A series of one-way analysis of variance were used to investigate the occurrence of empathic behaviours in our sample, as follows. First, we analysed the overall occurrence of empathy per se as a function of interviewer gender. Our results revealed that female interviewers displayed more empathic behaviours (Mfemaleempathy=18.89, SD=5.92), 95% CI [16.94, 21.83], than the male interviewers, (Mmaleempathy=8.17, SD=3.65), 95% CI [10.35, 9.98], F(1, 35)=42.74, p < .001, η2=.55. We then analysed the occurrence of the four types of empathy as a function of gender, again our results revealed significant differences for three of the four empathic behaviours. Female interviewers displayed considerably more spontaneous comfort (Mfemale spontaneous comfort=9.33, SD=3.85), 95% CI [1.33, 3.01], F(1, 35)=30.28, p < .001, η2=.47, spontaneous understanding, (Mfemale spontaneous understanding=4.40, SD = 2.07), 95% CI [2.09, 5.29], F(1, 35) = 9.56, p = .004, η2 = .21, and continuer understanding (Mfemale continuer understanding = 3.28, SD = 1.18), 95% CI [1.69, 2.86], F(1, 35) = 14.04, p = .001, η2 = .29, than male interviewers, (Mmale spontaneous comfort = 3.44, SD = 2.41), 95% CI [0.50, 1.61], (Mmale spontaneous understanding = 2.61, SD = 2.17), 95% CI [1.53, 3.36], and (Mmale continuer understanding = 1.08, SD = 0.72), 95% CI [0.69, 1.42]. No significant differences emerged (applying Bonferoni's correction) across gender for continuer comfort, F = 5.44, p = .029, (Mfemale continuer comfort = 2.17, SD = 1.69, Mmale continuer comfort = 1.66, SD = 1.69).

Empathic OpportunitiesSpontaneous empathy (here spontaneous comfort and spontaneous understanding) could be described as ‘standalone’ verbal behaviours, which emanate from the police interviewer in the absence of any preceding ‘trigger’ behaviours (e.g., verbal statements/behaviours and/or physical indicators). On the other hand, continuer empathy is vicarious, that is it is occurs following the actions of another, here the interviewee. Hence, it is sensible to not only measure the occurrence and frequency of interviewer continuer behaviour (as above), but also to consider the presence of continuer opportunities in the sample, which will allow us to understand whether opportunities are being missed, that is whether they have not been continued but rather ‘terminated’ by the interviewer, or whether they simply do not arise. It is entirely possible that the apparent disparity in the occurrence of spontaneous versus continuer empathy may have resulted from reduced empathic opportunities.

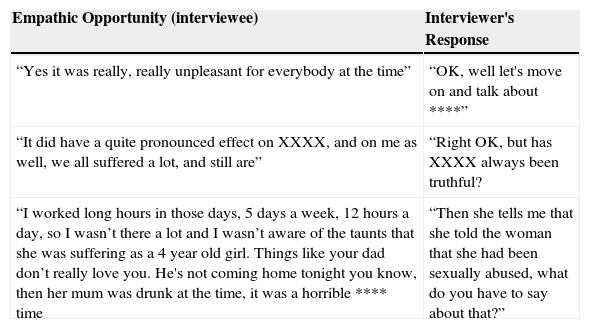

In line with previous research, an empathic opportunity is defined as when an interviewee “provides some kind of information, consciously or otherwise, in the hope that the interviewer will respond” (Oxburgh & Ost, 2011, p. 184). For the purposes of this research, we confine ourselves to verbal information, only. Overall, the mean number of empathic opportunities per interview (which we do not categorise as being either comfort or understanding) was 7.91, ranging from three to eleven (SD = 2.15). A one-way analysis of variance for the number of opportunities as a function of interviewer gender (that is the number of opportunities that occurred in the interviews being conducted by female interviewers compared to male interviewers) revealed a significant difference, F(1, 35) = 6.67, p = .014, η2 = .16 (see Table 4 for exemplars of opportunities, and the interviewer's response). The mean number of opportunities for female interviewers was higher (M = 8.28, SD = 2.02), than for male interviewers (M = 6.55, SD = 1.97).

Representative Examples of Missed Empathic Opportunities and Interviewer's Reply

| Empathic Opportunity (interviewee) | Interviewer's Response |

|---|---|

| “Yes it was really, really unpleasant for everybody at the time” | “OK, well let's move on and talk about ****” |

| “It did have a quite pronounced effect on XXXX, and on me as well, we all suffered a lot, and still are” | “Right OK, but has XXXX always been truthful? |

| “I worked long hours in those days, 5 days a week, 12hours a day, so I wasn’t there a lot and I wasn’t aware of the taunts that she was suffering as a 4 year old girl. Things like your dad don’t really love you. He's not coming home tonight you know, then her mum was drunk at the time, it was a horrible **** time | “Then she tells me that she told the woman that she had been sexually abused, what do you have to say about that?” |

This research reports an investigation of empathic communication in the field with suspected sex offenders. We considered types of empathy, whether male and female police interviewers differed in the type and occurrence of empathic behaviours displayed, and missed empathic opportunities. First, we used grounded theory to identify types of empathy – four distinct types emerged, which we have labelled as spontaneous (stand-alone, interviewer initiated verbal utterances) comfort and understanding, and continuer (utterances immediately following an empathic opportunity offered by the suspect) comfort and understanding. Overall, the spontaneous empathy behaviours occurred significantly more often (approximately 6 times during each interview) than the continuer empathies (which on average occurred less than twice in each interview). The former were used consonantly by all of the officers (irrespective of gender) in the sample despite being employed by two different police forces.

The spontaneous empathies appeared rather systematic in nature because typically they simply prefaced verbal information given to the interviewee during the ‘engage and explain’ phase of the interview where processes/procedures, and the topics/events to be discussed were explained to the interviewee. Here, interviewees did not interact verbally with the interviewer, but instead were passive receivers. Hence, it could be argued that this type of non-cognitive empathy is not pro-social, which may serve to reduce, rather than scaffold cooperation. Uninvited, automatic non-experienced empathy might be negatively interpreted and poorly received by the interviewee (e.g., Cuff et al., 2014; Maijala, Åstedt-Kurki, Paavilainen, & Väisänen, 2003; Tansey & Burke, 2013), and so may not be followed by the same behavioural responses as empathy emanating from perceived empathic opportunities (see Gerdes & Segal, 2009; Geer, Estupinan, & Manguno-Mire, 2000; Hodges & Biswas-Diener, 2007).

On the other hand, continuer empathy was less automatic, and more cognitive in nature: it was interviewee driven, and relied on the interviewer recognizing an empathic opportunity and continuing it. Effortful, more complex cognition, such as that displayed by some of the interviewers when recognizing and responding to an empathic opportunity has been found to amplify behavioural responses (Cuff et al., 2014; also see de De Vignemont & Singer, 2006; Eisenberg & Miller, 1987). While the experience that is understood by the interviewer remains that of the interviewee, this type of state empathy is associated with prosocial behaviour (e.g., Hein, Salini, Preuschoff, Basoton, & Singer, 2010; Williams, O’Driscoll, & Moore, 2014), and in clinical settings is linked to improved outcomes and levels of satisfaction (see Gleichgerrcht & Decety, 2013).

Despite an average of eight continuer empathy opportunities provided by suspects in each interview, continuer empathy occurred very infrequently. However, that officers did not continue the majority of empathic opportunities raises two possibilities. First, a lack of knowledge/training concerning the use of empathy may have meant that officers simply did not recognize this type of empathic opportunity. Second, that officers ignored, rather than missed these opportunities. However, despite a lack of empathic training, we found that some officers in our sample did exhibit continuer behaviour, which suggests that some police interviewers may be intrinsically more empathic than others.

Why might officers ignore or terminate empathic opportunities? Social constructionist accounts suggest that empathy is not an automatic or inevitable social behaviour (see Lock & Strong, 2010). Rather, it is an effortful type of sociality that supports the development of dispositions and actions amid a set of social conditions. The negative underpinnings of such effortful non-automatic empathy imply ‘choosing a side… favouring one who is more closely like one's self’ (Brown, 2012), which may provide a framework for understanding why police officers might ignore and/or terminate empathic opportunities. Continuer empathy may be inherently uncomfortable for police interviewers who have consistently reported finding interview encounters with suspected sex offenders extremely demanding (Soukara, Bull, & Vrij, 2002). As a consequence officers may choose, consciously or otherwise, not to ‘use’ this type of empathy during suspect interviews, which are unchosen relationships within which they may believe there is little room for shared feeling or emotional attunement (also see Oxburgh et al., 2015).

All interviews with suspected offenders are audio recorded in England and Wales, and so police officers are aware that their verbal behaviour may be scrutinised by, among others, their peers. Empathising, other than in an automatic, systematic manner, may be perceived as loosing and/or being seen to lose a sense of one's self, behaviour that officers may not want to display, or seen to be displaying. Future research should seek to investigate police officer's perceptions of investigative empathy, comparing more automatic spontaneous and non-automatic continuer empathy with reference to social constructionist accounts.

Turning to gender, we found that female interviewers displayed significantly more empathic behaviour per se by a considerable margin (more than double the amount). Irrespective of the unique and complex nature of suspect interviews, this finding fits well with literature pertaining to cross gender empathic behaviour (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004). However, when considering types of empathy our findings may be less positive than they first appear because this type of non-cognitive, uninvited empathy maybe less pro-social than interview driven empathy (see Brown, 2012; Hein et al., 2010). Female interviewers actually displayed significantly more spontaneous empathy than men. Given that this type of empathy may at best be ineffective and at worst counterproductive, this finding has negative proclivities. That said, females were also found to display one of the two types of continuer empathy more often than men (continuer understanding), which might be important for scaffolding cooperation. However, it should be noted that females were also ‘offered’ more empathic opportunities than male interviewers.

Future Research and LimitationsFuture research should consider investigating whether the types of empathic behaviours that have emerged from this study do affect information revelation. That said, using transcripts and recordings from real life interviews with suspects would be challenging on several counts. For example, deciding what constitutes investigation relevant information is subjective, particularly in the absence of ground truth. However, experimental laboratory investigations of the efficacy of empathic behaviour for information gain, including manipulating communication skill sets, and which draw on the paradigms employed by persuasion researchers, might prove fruitful, but could lack ecological validity.

If it transpires that continuer empathy is important for increasing information gain in suspect interviews, it may be that officers might be psychometrically assessed for empathy prior to being selected for advanced interview training (e.g., see Lietz et al., 2011). High trait empathy individuals have been found to display greater experienced empathy than low trait individuals under cognitive load, indicating that empathy may be more automatic for some (Rameson, Morelli, & Lieberman, 2012). Future research should also seek to investigate gender and empathy in suspect interviews, paying particular attention to whether/how gender might affect cooperation and information gain, in both the presence and absence of the two different types of empathy highlighted by this research. To date, this aspect of interviewing/interrogative techniques has received very little attention, particularly in Europe. However, researchers in Japan have recently reported that a relationship-focused interviewing style resulted in increased information gain and more confessions compared with an evidence-focused approach to interviewing (Wachi et al., 2014).

The limitations of this research must also be borne in mind when interpreting and considering our findings and suggestions. First, because our data was ‘real’ we were unable to control all of the variables that might have had some bearing on our results. For example, we are unaware of whether the suspects being interviewed were guilty or innocent of the offences about which they were questioned. We have not considered information gain with reference to the emergent empathic behaviours for reasons already discussed (subjectivity, no ground truth, no information regarding findings of guilt/innocence). Additionally, here we were unable to contact (due to ethical constraints) either the interviewers or the suspects to establish additional information.

To conclude, this research has gone someway toward developing a taxonomy of investigative empathy and provides a strong indication that blanket definitions of empathy are likely to have masked previous attempts to understand this type of pro-social behaviour during a suspect interview/interrogation. Additional research needs to be undertaken in this domain because there is much to suggest that interviewing might be more effective if interviewers were assisted to recognise and act upon empathic opportunities. This research topic is particularly timely, not only for the purposes of crime investigation, but also for developing effective intelligence-gathering techniques (see Dando & Tranter, 2015). Given that many countries worldwide are seeking to develop non-coercive, dynamic, intelligence/information-gathering methods, investigative empathy may support interviewers to develop an operational accord, or special ‘working’ or ‘professional’ relationship with an interviewee, a relationship that is characterised by a willingness to supply accurate information in response to an interviewer's questions.

Conflict of InterestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

From here on ‘suspects’ is used to describe people who are suspected of having committed an offence, and who are being formally investigated.

These data are unique and have not been analysed in prior published research.

Such information includes the suspect's legal right to remain silent, to have a legal advisor present, and what will happen to the video/audio recordings when the interview is finished.