Introduction. Liver disease is a major health issue in Mexico. Although several studies have been performed to analyze the impact of liver diseases on the Mexican population, none has compared the prevalence and impact of liver disease between states within Mexico. AIM: To analyze trends in mortality associated with liver diseases from 2000 to 2007 at the national and state levels.

Methods. Data was obtained from the Ministry of Health (number of deaths) and the National Population Council (CONAPO) (population at risk) and mortality rates were analyzed using statistical software.

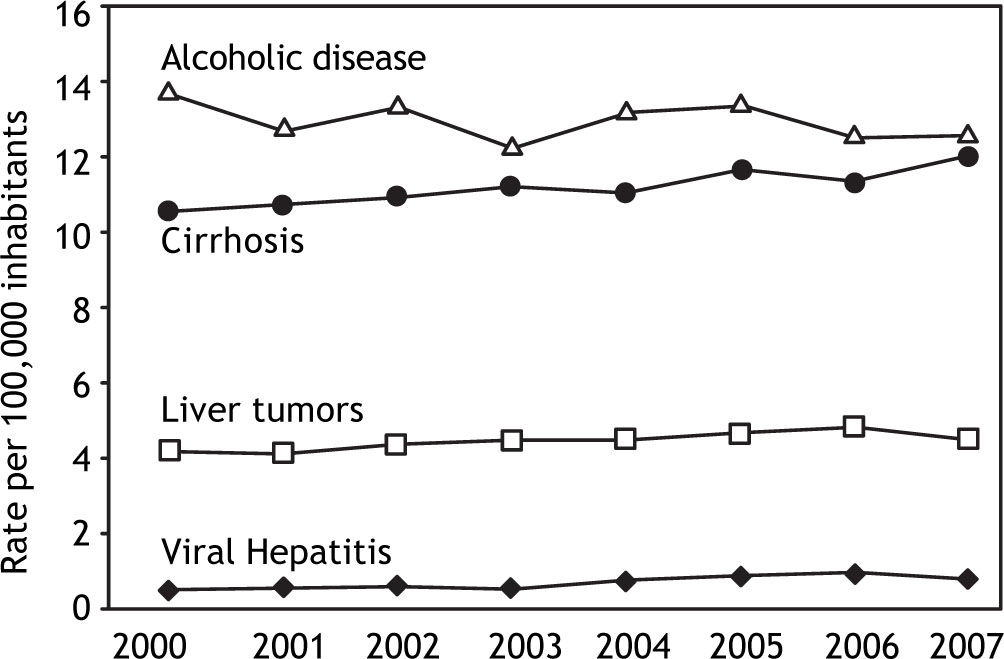

Results. Mortality due to viral hepatitis, liver tumors, and cirrhosis increased over the study period. Alcohol-related mortality decreased but was still the main cause of liver-related deaths. Viral hepatitis infection occurred predominantly in the northern states and liver tumors occurred predominantly in the central region. Alcohol-related deaths were elevated along the Pacific shoreline and deaths associated with cirrhosis occurred mainly in the central and southern states.

Conclusion. Incidence of liver-related mortality has increased and will continue to do so in the future.

Liver diseases are a major health issue worldwide and their incidence is expected to increase. In Mexico, cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases are considered among the main causes of mortality since 2000. Their incidence and prevalence have increased to the extent that they were responsible for 20,941 deaths in 2007.1 The increase in liver disease-related deaths has been confirmed and it was concluded that it will increase further in the next decade.2

Liver diseases may be secondary to several etiologies. Alcohol consumption is one of the most important risk factors for liver deterioration. It has been demonstrated that ethanol disrupts hepatic proteins and enzyme function, which promotes lipid infiltra-tion.3 Likewise, metabolic features such as obesity (especially abdominal obesity, i.e., an excessive waist circumference or waist-hip index), insulin resistance and the associated impairment of glucose metabolism, and dyslipidemia all induce liver steato-sis and fibrosis.4,5 Some infections, especially hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections, may induce a proinflammatory state conducive to liver damage and accumulation of lipids.6

Viral hepatitis infection is common in Mexico. Some of these infections are considered hepatotropic (infections with hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D, E, and F), and others are considered nonhepatotropic (infections with cytomegalovirus, herpes virus, and Eps-tein-Barr virus). Most of these agents are capable of inducing acute infections, but only hepatitis viruses B, C, D, and E cause chronic liver disease.7 An in-crease in the prevalence and incidence of these infections, especially chronic infections, has been noted. In 2008, 1,107 cases of infection with HBV and 2,226 cases of HCV infection were reported, equivalent to an incidence of 1.04 and 2.09 per 100,000 inhabitants, respectively. As with other chronic liver diseases, the number of cases of HCV and HCB infection is expected to increase in the future.8

Metabolic and infective causes of liver damage both result in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, which may cause nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Alcohol consumption may cause liver steatosis and cirrhosis. Irrespective of the pathway by which liver damage is incurred, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma are the immediate causes of death.9

It is important to note that the Mexican population is prone to metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is characterized by insulin resistance, abdominal obesity, atherogenic dyslipidemia, elevated blood pressure, and a proinflammatory pro-thrombotic state. It has recently been associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. According to the Adult Treatment Panel III diagnostic criteria, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Mexico is 26.6%, and most cases are adults.10 Nevertheless, the incidence of metabolic syndrome among the pe-diatric population is expected to increase because pediatric obesity is increasing. The prevalence of obesity among children was 27.2% in 2000,11 which corresponds with the 26% prevalence reported by the 2006 Health and Nutrition National Survey.12 The prevalence of obesity among children and adults in Mexico is now among the highest worldwide. Therefore, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and chronic liver diseases is expected to increase in the future.

Although liver disease-associated morbidity and mortality have been studied at a national level, health conditions differ widely between the 31 states of Mexico. Although several reports have been published on the demographics of these diseases in various regions, it is necessary to collate all data according to state and time to elucidate the impact of liver disease in Mexico. The aim of this study is to analyze national and regional liver-related mortality trends in Mexico.

MethodsPopulationOfficial open-access databases were used to obtain data on deaths registered by the Ministry of Health of Mexico. The causes of death were classified in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases (10th revision), and the following pathologies were analyzed: viral hepatitis (codes B16.1-B16.9, B17.0-B17.8, and B18.0-B18.9), liver malignant tumors (codes C22.0-C22.9), alcoholic liver disease (codes K70.0-K70.9), and fibrosis and cirrhosis (codes K74.0 - K74.6). To estimate mortality rates, National Population Council (CONAPO) data on the population at risk was used as denominators. Mortality rates are reported according to sex, age (0-29, 30-49, 50-69, and ≥ 70 years), and state.

Statistical analysisDatabases were compiled using Microsoft Office Excel 2007 software (Microsoft Office Enterprise 2007) and statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics v.17 software (LEAD Technologies, Chicago, IL). Rates are expressed per 100,000 inhabitants. Mortality rates between 2000 and 2007 were analyzed using linear regression to identify temporal trends.

ResultsThe national-level analysis showed an increase in liver-related mortality over the study period, which was closely related to age. Age plays an important role in the pathogenesis of liver disease because most cases occur in people older than 75 years; nevertheless, liver disease is also important for younger people because the mortality rate associated with liver disease begins to increase from the age of 30.

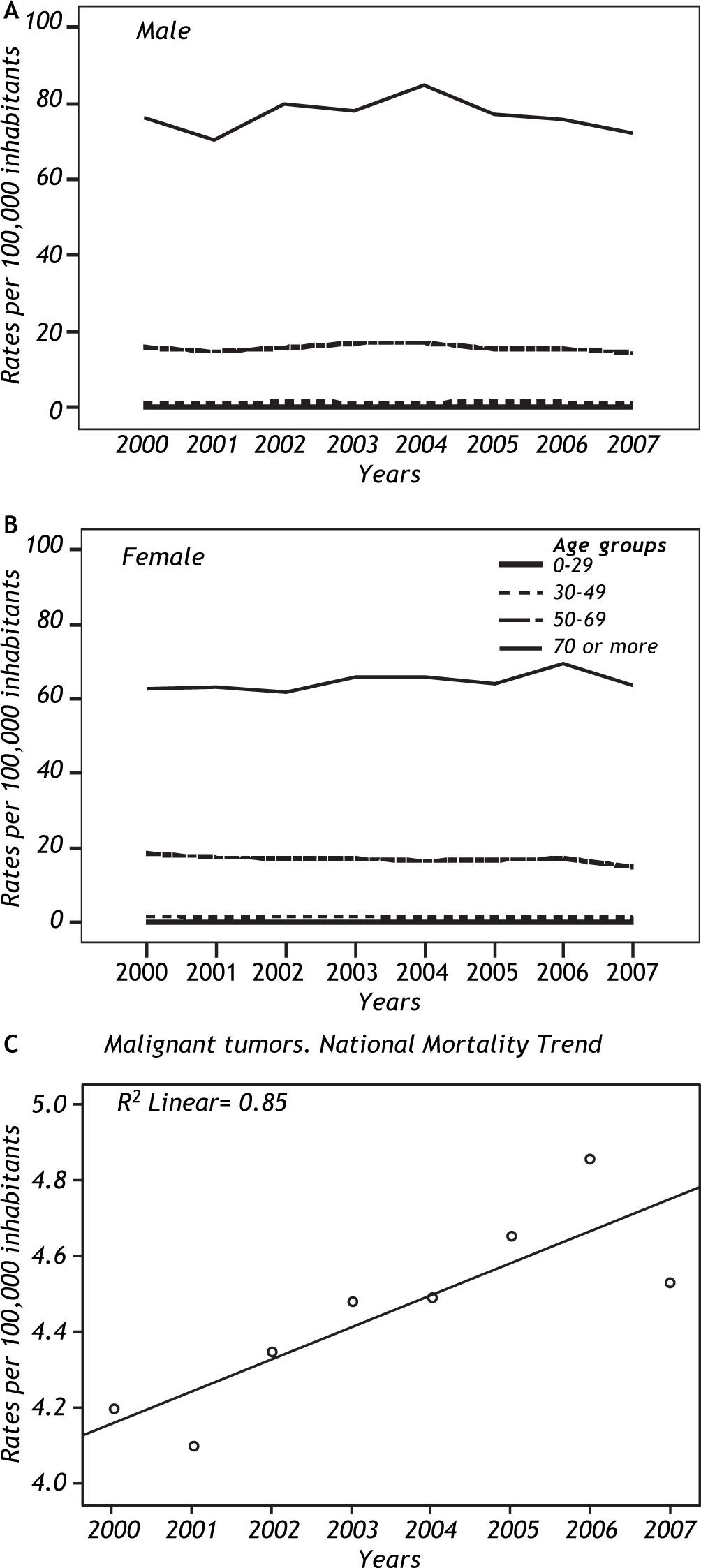

When mortality trends were compared according to the type of disease, it was found that the incidence of viral hepatitis-, tumor-, and cirrhosis-related mortality increased, whereas that of alcohol-related death decreased, even though it was still the main cause of liver-related mortality (Figure 1).

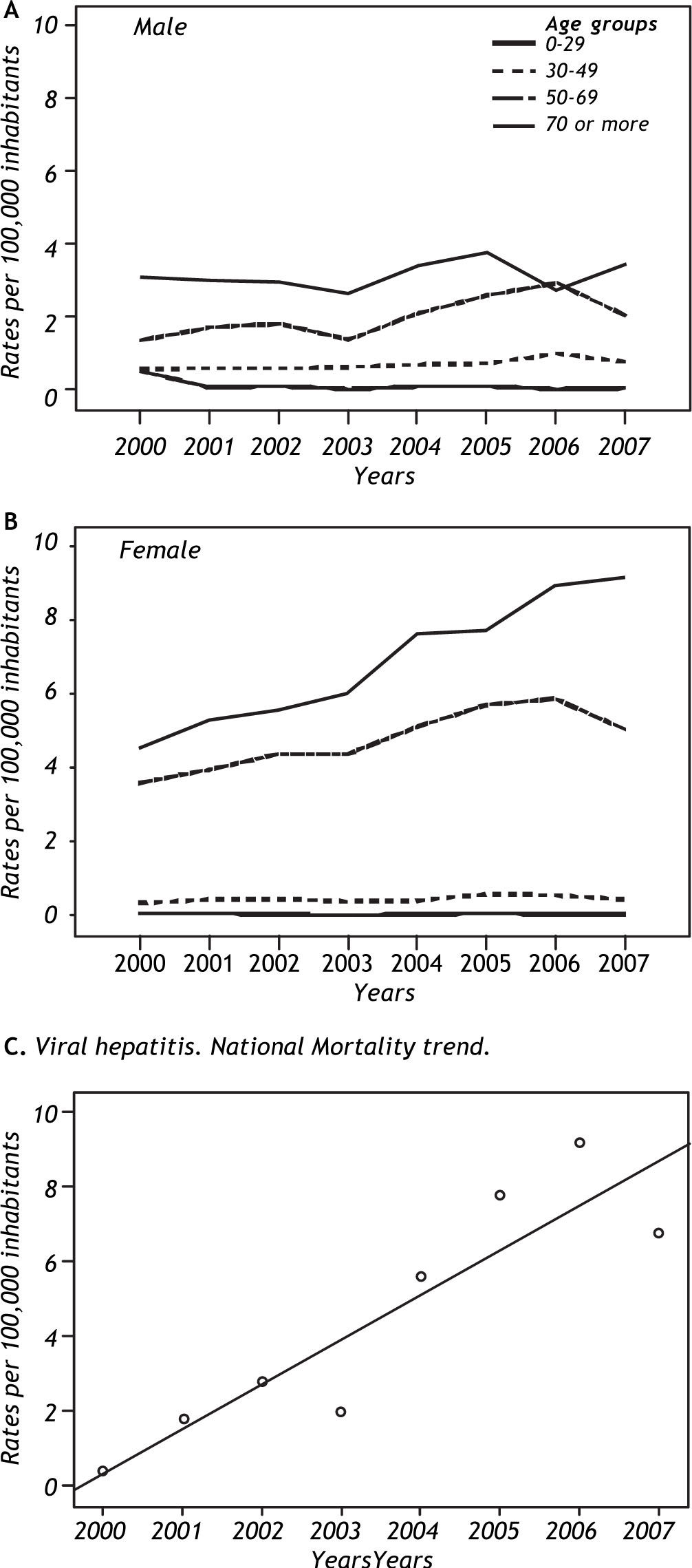

When analyzed according to sex and liver disease, mortality due to viral hepatitis (Figure 2, panel A and B) increased over the study period. The increase was much higher among women than among men.

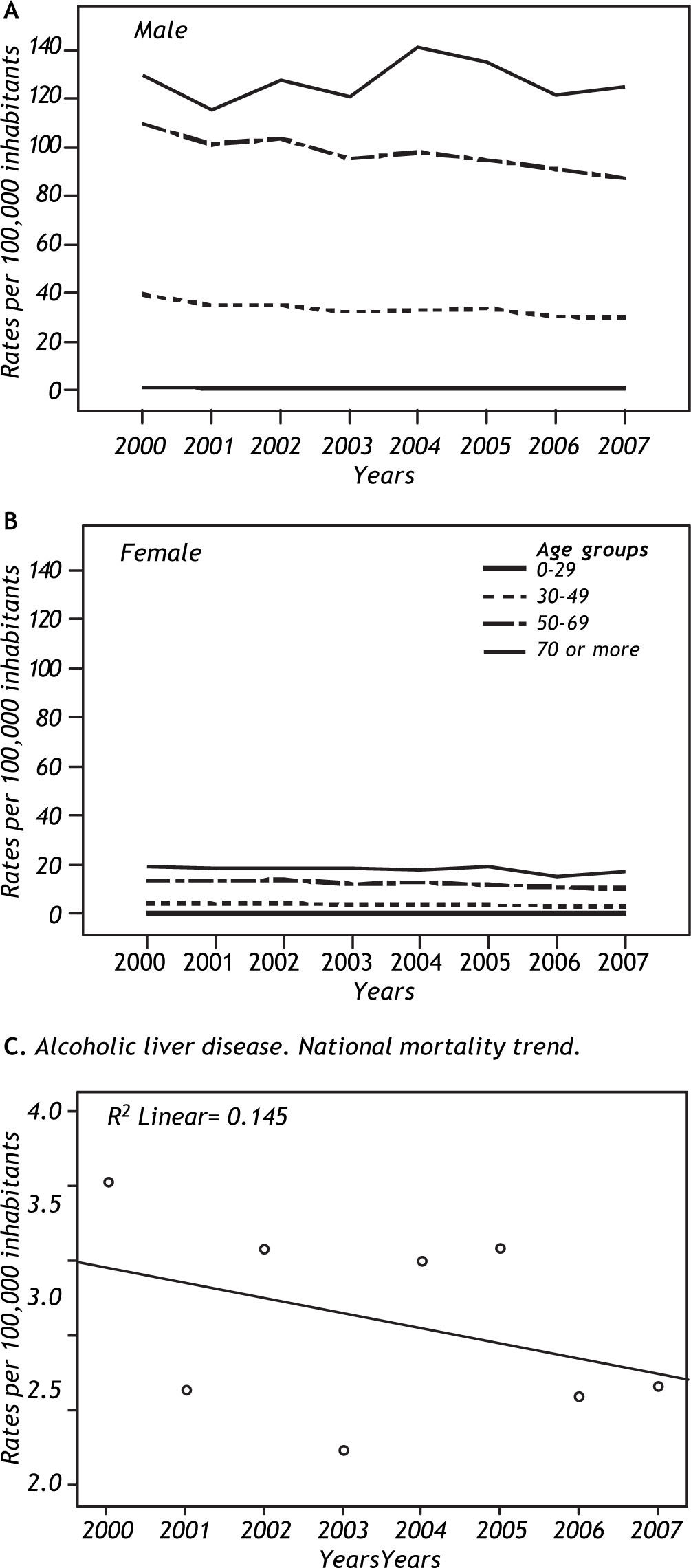

The incidence of alcohol-related liver disease (Figure 3, panel A and B) was much lower among women than men but it decreased with time among men. However, it still has a strong impact on the national mortality trend.

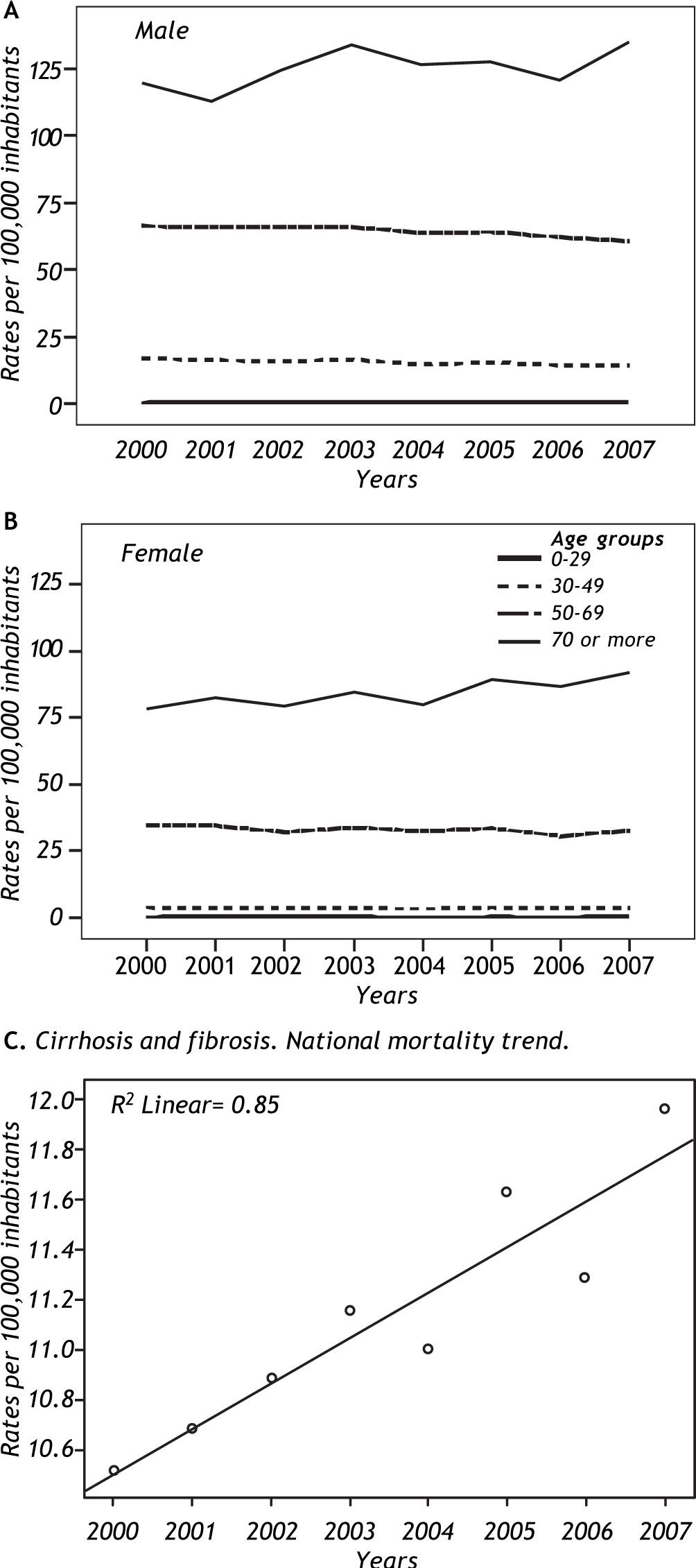

Mortality due to cirrhosis (Figure 4, panel A and B) was higher in men. Unlike alcohol-related mortality, women had a greater incidence of cirrhosis; nevertheless, cirrhosis-related deaths increased during the study period, becoming almost as great as those associated with alcohol.

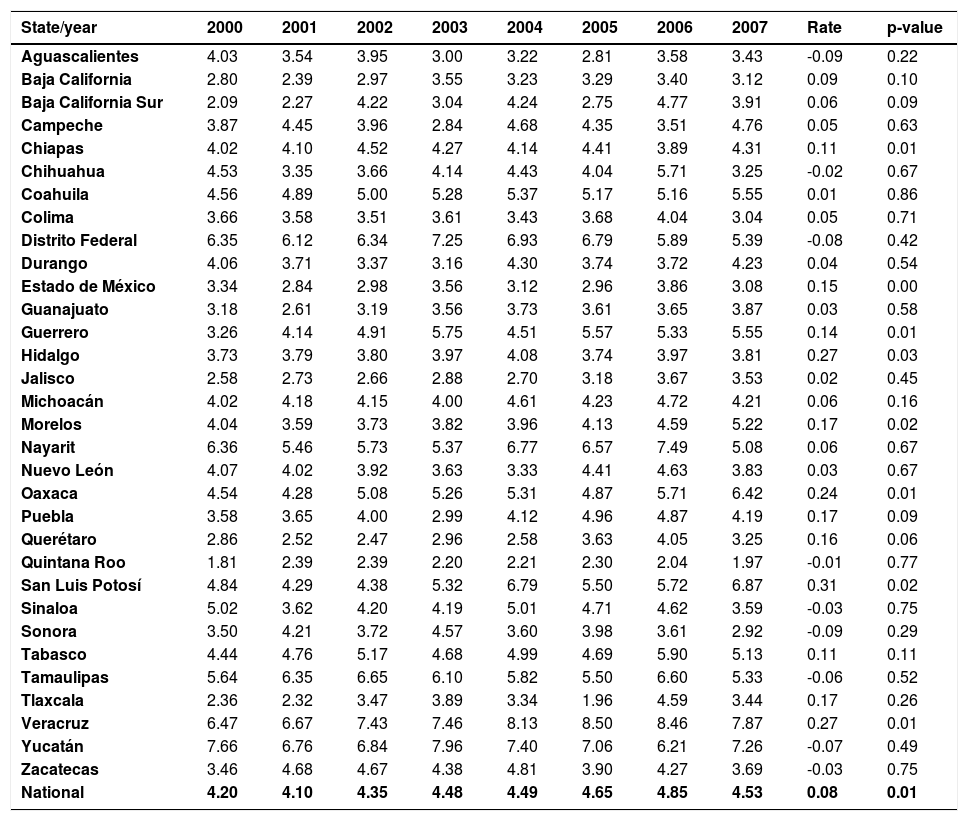

Malignant tumor-related mortality (Figure 5, panel A and B) showed a lower trend than cirrhosis or alcohol, although it tended to increase. Rates for men and women were very similar.

Panel C in each of the figures cited above shows a linear regression for each of the four groups of pathologies studied. The linear regressions confirm that the incidence of alcoholic mortality decreased over the study period and that the incidence of mortality associated with viral hepatitis, malignant tumors, and cirrhosis increased over the study period.

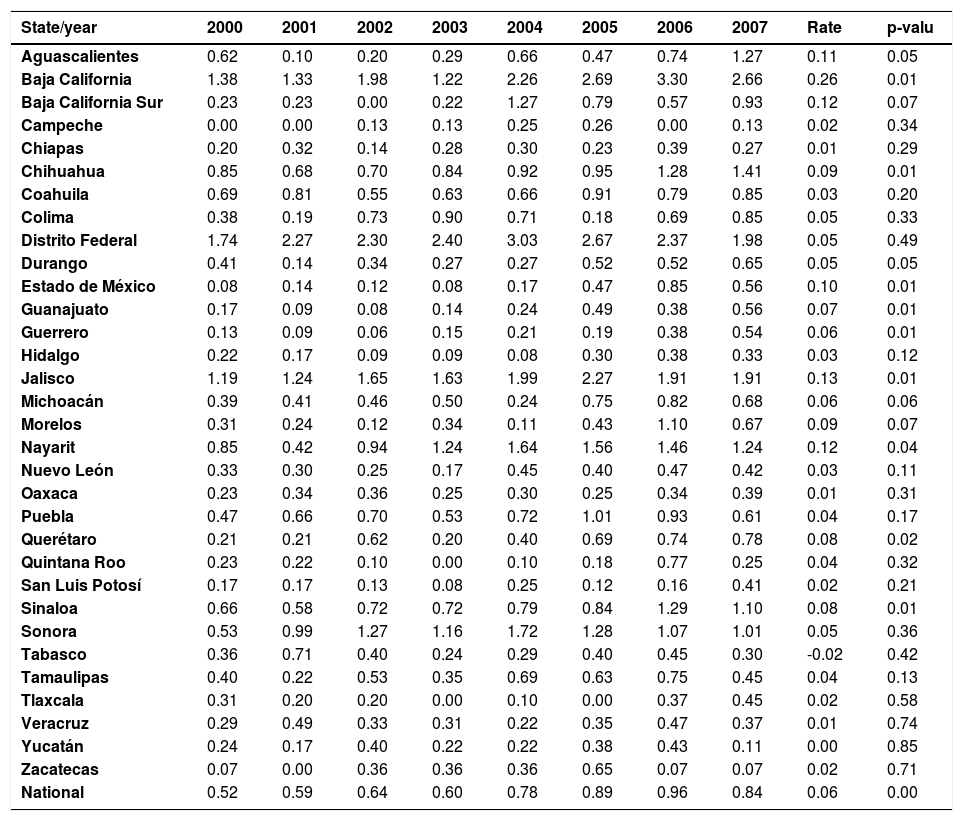

Mortality associated with viral hepatitis increased in the northern states (Baja California, Jalisco, and Nayarit), Aguascalientes, Estado de México, and Chihuahua. The highest overall mortalities were in Distrito Federal, Baja California, and Jalisco.

Although the highest incidence of hepatic tumor-related mortality occurred in Veracruz, Yucatán, and Distrito Federal, the incidence of hepatic tumor-related mortality increased in San Luis Potosí, Veracruz, Hidalgo, and Oaxaca. Hepatic tumor-related mortality appeared to decrease in some of the other states but the decrease was not statistically significant.

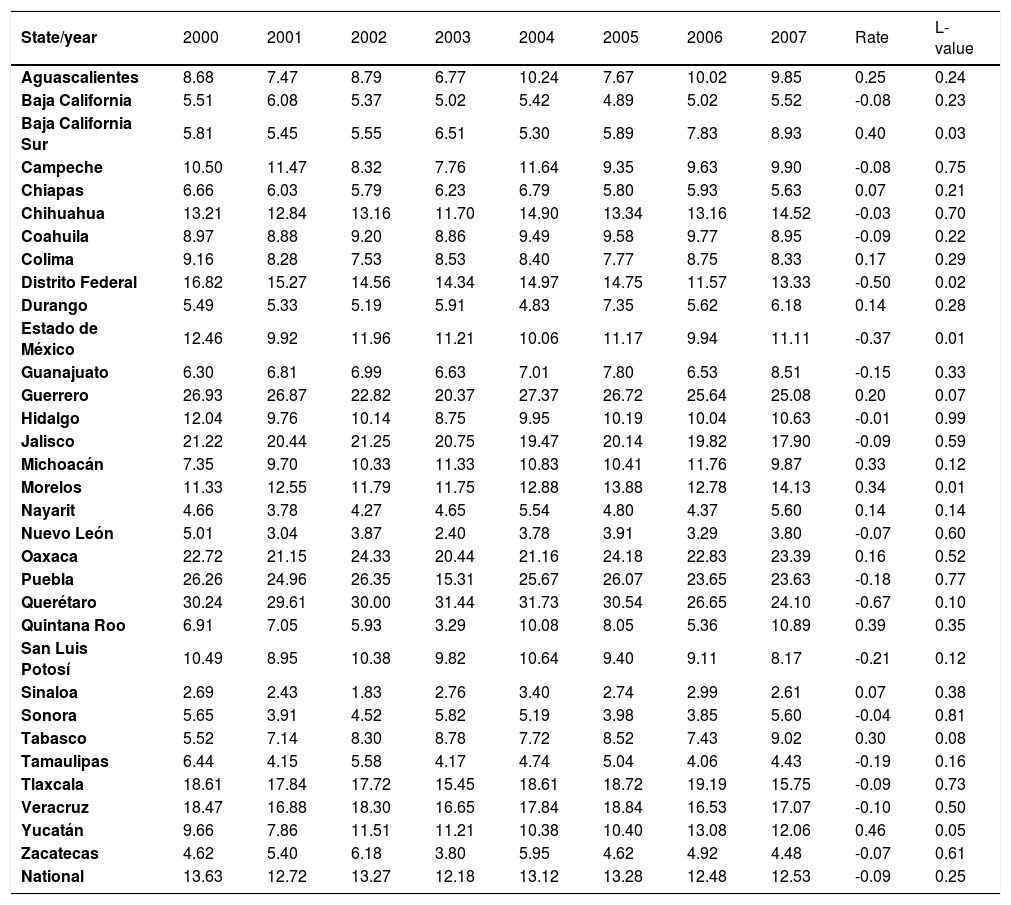

Although alcohol-related mortality decreased at the national level, trends varied between states. Querétaro, Guerrero, and Puebla had the highest rates of alcohol-related mortality, whereas Yucatán, Baja California Sur, Morelos, and Michoacán had the highest increase in alcohol-related deaths. The incidence of alcohol-related mortality decreased in Distrito Federal, Estado de México, and Querétaro.

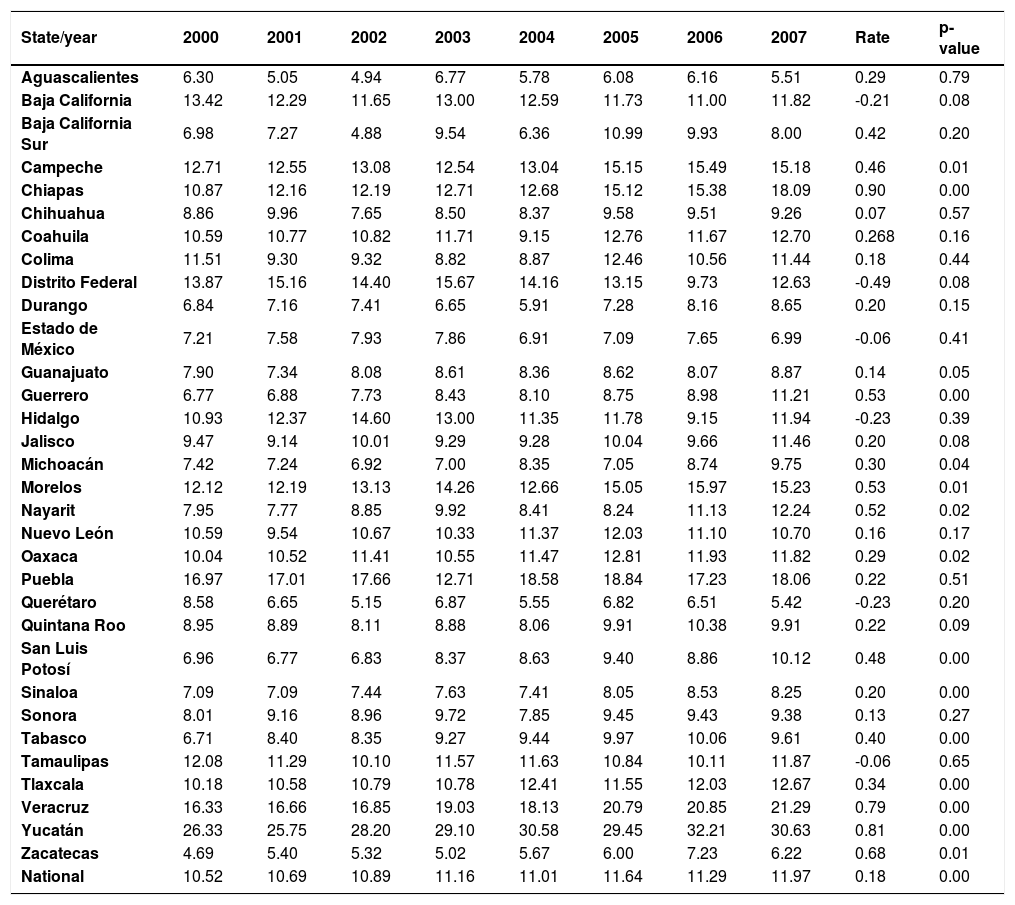

Cirrhosis-and fibrosis-related mortality increased in Chiapas, Yucatán, and Veracruz, and by 2007 it was almost as high as alcohol-related mortality. Yucatán, Veracruz, and Puebla had the highest rates, but it is important to note that rates decreased in some central states over the study period.

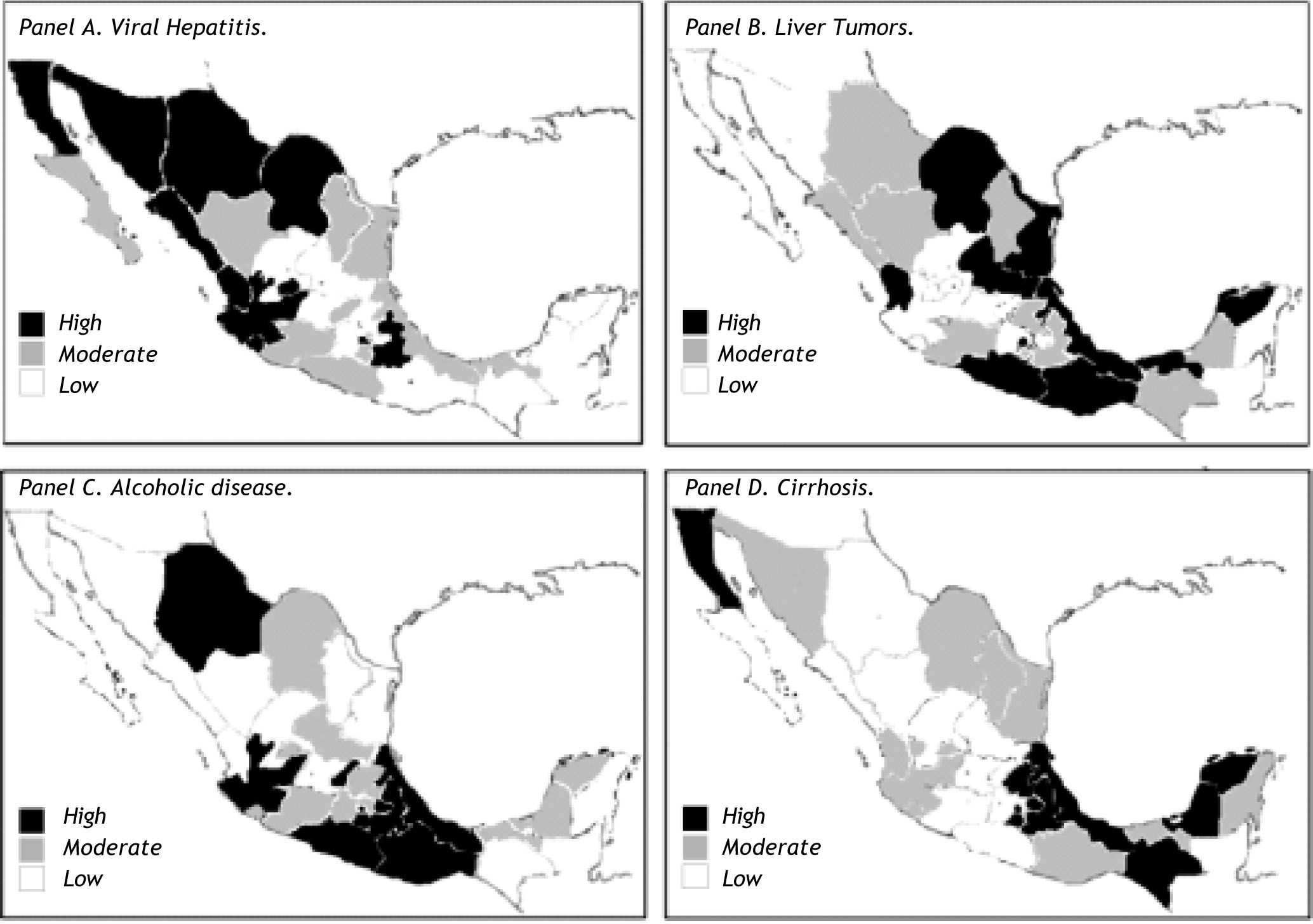

Mortality according to state and year is presented on Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4. Figure 6 shows the states with the highest mortality rates during this period according to each of the pathologies studied.

Mortality rate due to viral hepatitis for each state and for the nation for 2000-2007.

| State/year | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | Rate | p-valu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguascalientes | 0.62 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.74 | 1.27 | 0.11 | 0.05 |

| Baja California | 1.38 | 1.33 | 1.98 | 1.22 | 2.26 | 2.69 | 3.30 | 2.66 | 0.26 | 0.01 |

| Baja California Sur | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 1.27 | 0.79 | 0.57 | 0.93 | 0.12 | 0.07 |

| Campeche | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.34 |

| Chiapas | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.29 |

| Chihuahua | 0.85 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.84 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 1.28 | 1.41 | 0.09 | 0.01 |

| Coahuila | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.91 | 0.79 | 0.85 | 0.03 | 0.20 |

| Colima | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.73 | 0.90 | 0.71 | 0.18 | 0.69 | 0.85 | 0.05 | 0.33 |

| Distrito Federal | 1.74 | 2.27 | 2.30 | 2.40 | 3.03 | 2.67 | 2.37 | 1.98 | 0.05 | 0.49 |

| Durango | 0.41 | 0.14 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.65 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Estado de México | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.47 | 0.85 | 0.56 | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| Guanajuato | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.56 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| Guerrero | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Hidalgo | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| Jalisco | 1.19 | 1.24 | 1.65 | 1.63 | 1.99 | 2.27 | 1.91 | 1.91 | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| Michoacán | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.24 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Morelos | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.43 | 1.10 | 0.67 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Nayarit | 0.85 | 0.42 | 0.94 | 1.24 | 1.64 | 1.56 | 1.46 | 1.24 | 0.12 | 0.04 |

| Nuevo León | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| Oaxaca | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 0.31 |

| Puebla | 0.47 | 0.66 | 0.70 | 0.53 | 0.72 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 0.61 | 0.04 | 0.17 |

| Querétaro | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.62 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.69 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| Quintana Roo | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.77 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.32 |

| San Luis Potosí | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 0.21 |

| Sinaloa | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 1.29 | 1.10 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Sonora | 0.53 | 0.99 | 1.27 | 1.16 | 1.72 | 1.28 | 1.07 | 1.01 | 0.05 | 0.36 |

| Tabasco | 0.36 | 0.71 | 0.40 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.30 | -0.02 | 0.42 |

| Tamaulipas | 0.40 | 0.22 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 0.69 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.13 |

| Tlaxcala | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 0.58 |

| Veracruz | 0.29 | 0.49 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.74 |

| Yucatán | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.40 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.85 |

| Zacatecas | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.65 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.71 |

| National | 0.52 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

Mortality rate due to alcoholic liver disease for each state and for the nation for 2000-2007.

| State/year | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | Rate | L-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguascalientes | 8.68 | 7.47 | 8.79 | 6.77 | 10.24 | 7.67 | 10.02 | 9.85 | 0.25 | 0.24 |

| Baja California | 5.51 | 6.08 | 5.37 | 5.02 | 5.42 | 4.89 | 5.02 | 5.52 | -0.08 | 0.23 |

| Baja California Sur | 5.81 | 5.45 | 5.55 | 6.51 | 5.30 | 5.89 | 7.83 | 8.93 | 0.40 | 0.03 |

| Campeche | 10.50 | 11.47 | 8.32 | 7.76 | 11.64 | 9.35 | 9.63 | 9.90 | -0.08 | 0.75 |

| Chiapas | 6.66 | 6.03 | 5.79 | 6.23 | 6.79 | 5.80 | 5.93 | 5.63 | 0.07 | 0.21 |

| Chihuahua | 13.21 | 12.84 | 13.16 | 11.70 | 14.90 | 13.34 | 13.16 | 14.52 | -0.03 | 0.70 |

| Coahuila | 8.97 | 8.88 | 9.20 | 8.86 | 9.49 | 9.58 | 9.77 | 8.95 | -0.09 | 0.22 |

| Colima | 9.16 | 8.28 | 7.53 | 8.53 | 8.40 | 7.77 | 8.75 | 8.33 | 0.17 | 0.29 |

| Distrito Federal | 16.82 | 15.27 | 14.56 | 14.34 | 14.97 | 14.75 | 11.57 | 13.33 | -0.50 | 0.02 |

| Durango | 5.49 | 5.33 | 5.19 | 5.91 | 4.83 | 7.35 | 5.62 | 6.18 | 0.14 | 0.28 |

| Estado de México | 12.46 | 9.92 | 11.96 | 11.21 | 10.06 | 11.17 | 9.94 | 11.11 | -0.37 | 0.01 |

| Guanajuato | 6.30 | 6.81 | 6.99 | 6.63 | 7.01 | 7.80 | 6.53 | 8.51 | -0.15 | 0.33 |

| Guerrero | 26.93 | 26.87 | 22.82 | 20.37 | 27.37 | 26.72 | 25.64 | 25.08 | 0.20 | 0.07 |

| Hidalgo | 12.04 | 9.76 | 10.14 | 8.75 | 9.95 | 10.19 | 10.04 | 10.63 | -0.01 | 0.99 |

| Jalisco | 21.22 | 20.44 | 21.25 | 20.75 | 19.47 | 20.14 | 19.82 | 17.90 | -0.09 | 0.59 |

| Michoacán | 7.35 | 9.70 | 10.33 | 11.33 | 10.83 | 10.41 | 11.76 | 9.87 | 0.33 | 0.12 |

| Morelos | 11.33 | 12.55 | 11.79 | 11.75 | 12.88 | 13.88 | 12.78 | 14.13 | 0.34 | 0.01 |

| Nayarit | 4.66 | 3.78 | 4.27 | 4.65 | 5.54 | 4.80 | 4.37 | 5.60 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| Nuevo León | 5.01 | 3.04 | 3.87 | 2.40 | 3.78 | 3.91 | 3.29 | 3.80 | -0.07 | 0.60 |

| Oaxaca | 22.72 | 21.15 | 24.33 | 20.44 | 21.16 | 24.18 | 22.83 | 23.39 | 0.16 | 0.52 |

| Puebla | 26.26 | 24.96 | 26.35 | 15.31 | 25.67 | 26.07 | 23.65 | 23.63 | -0.18 | 0.77 |

| Querétaro | 30.24 | 29.61 | 30.00 | 31.44 | 31.73 | 30.54 | 26.65 | 24.10 | -0.67 | 0.10 |

| Quintana Roo | 6.91 | 7.05 | 5.93 | 3.29 | 10.08 | 8.05 | 5.36 | 10.89 | 0.39 | 0.35 |

| San Luis Potosí | 10.49 | 8.95 | 10.38 | 9.82 | 10.64 | 9.40 | 9.11 | 8.17 | -0.21 | 0.12 |

| Sinaloa | 2.69 | 2.43 | 1.83 | 2.76 | 3.40 | 2.74 | 2.99 | 2.61 | 0.07 | 0.38 |

| Sonora | 5.65 | 3.91 | 4.52 | 5.82 | 5.19 | 3.98 | 3.85 | 5.60 | -0.04 | 0.81 |

| Tabasco | 5.52 | 7.14 | 8.30 | 8.78 | 7.72 | 8.52 | 7.43 | 9.02 | 0.30 | 0.08 |

| Tamaulipas | 6.44 | 4.15 | 5.58 | 4.17 | 4.74 | 5.04 | 4.06 | 4.43 | -0.19 | 0.16 |

| Tlaxcala | 18.61 | 17.84 | 17.72 | 15.45 | 18.61 | 18.72 | 19.19 | 15.75 | -0.09 | 0.73 |

| Veracruz | 18.47 | 16.88 | 18.30 | 16.65 | 17.84 | 18.84 | 16.53 | 17.07 | -0.10 | 0.50 |

| Yucatán | 9.66 | 7.86 | 11.51 | 11.21 | 10.38 | 10.40 | 13.08 | 12.06 | 0.46 | 0.05 |

| Zacatecas | 4.62 | 5.40 | 6.18 | 3.80 | 5.95 | 4.62 | 4.92 | 4.48 | -0.07 | 0.61 |

| National | 13.63 | 12.72 | 13.27 | 12.18 | 13.12 | 13.28 | 12.48 | 12.53 | -0.09 | 0.25 |

Mortality rate due to fibrosis and cirrhosis for each state and for the nation for 2000-2007.

| State/year | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | Rate | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguascalientes | 6.30 | 5.05 | 4.94 | 6.77 | 5.78 | 6.08 | 6.16 | 5.51 | 0.29 | 0.79 |

| Baja California | 13.42 | 12.29 | 11.65 | 13.00 | 12.59 | 11.73 | 11.00 | 11.82 | -0.21 | 0.08 |

| Baja California Sur | 6.98 | 7.27 | 4.88 | 9.54 | 6.36 | 10.99 | 9.93 | 8.00 | 0.42 | 0.20 |

| Campeche | 12.71 | 12.55 | 13.08 | 12.54 | 13.04 | 15.15 | 15.49 | 15.18 | 0.46 | 0.01 |

| Chiapas | 10.87 | 12.16 | 12.19 | 12.71 | 12.68 | 15.12 | 15.38 | 18.09 | 0.90 | 0.00 |

| Chihuahua | 8.86 | 9.96 | 7.65 | 8.50 | 8.37 | 9.58 | 9.51 | 9.26 | 0.07 | 0.57 |

| Coahuila | 10.59 | 10.77 | 10.82 | 11.71 | 9.15 | 12.76 | 11.67 | 12.70 | 0.268 | 0.16 |

| Colima | 11.51 | 9.30 | 9.32 | 8.82 | 8.87 | 12.46 | 10.56 | 11.44 | 0.18 | 0.44 |

| Distrito Federal | 13.87 | 15.16 | 14.40 | 15.67 | 14.16 | 13.15 | 9.73 | 12.63 | -0.49 | 0.08 |

| Durango | 6.84 | 7.16 | 7.41 | 6.65 | 5.91 | 7.28 | 8.16 | 8.65 | 0.20 | 0.15 |

| Estado de México | 7.21 | 7.58 | 7.93 | 7.86 | 6.91 | 7.09 | 7.65 | 6.99 | -0.06 | 0.41 |

| Guanajuato | 7.90 | 7.34 | 8.08 | 8.61 | 8.36 | 8.62 | 8.07 | 8.87 | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| Guerrero | 6.77 | 6.88 | 7.73 | 8.43 | 8.10 | 8.75 | 8.98 | 11.21 | 0.53 | 0.00 |

| Hidalgo | 10.93 | 12.37 | 14.60 | 13.00 | 11.35 | 11.78 | 9.15 | 11.94 | -0.23 | 0.39 |

| Jalisco | 9.47 | 9.14 | 10.01 | 9.29 | 9.28 | 10.04 | 9.66 | 11.46 | 0.20 | 0.08 |

| Michoacán | 7.42 | 7.24 | 6.92 | 7.00 | 8.35 | 7.05 | 8.74 | 9.75 | 0.30 | 0.04 |

| Morelos | 12.12 | 12.19 | 13.13 | 14.26 | 12.66 | 15.05 | 15.97 | 15.23 | 0.53 | 0.01 |

| Nayarit | 7.95 | 7.77 | 8.85 | 9.92 | 8.41 | 8.24 | 11.13 | 12.24 | 0.52 | 0.02 |

| Nuevo León | 10.59 | 9.54 | 10.67 | 10.33 | 11.37 | 12.03 | 11.10 | 10.70 | 0.16 | 0.17 |

| Oaxaca | 10.04 | 10.52 | 11.41 | 10.55 | 11.47 | 12.81 | 11.93 | 11.82 | 0.29 | 0.02 |

| Puebla | 16.97 | 17.01 | 17.66 | 12.71 | 18.58 | 18.84 | 17.23 | 18.06 | 0.22 | 0.51 |

| Querétaro | 8.58 | 6.65 | 5.15 | 6.87 | 5.55 | 6.82 | 6.51 | 5.42 | -0.23 | 0.20 |

| Quintana Roo | 8.95 | 8.89 | 8.11 | 8.88 | 8.06 | 9.91 | 10.38 | 9.91 | 0.22 | 0.09 |

| San Luis Potosí | 6.96 | 6.77 | 6.83 | 8.37 | 8.63 | 9.40 | 8.86 | 10.12 | 0.48 | 0.00 |

| Sinaloa | 7.09 | 7.09 | 7.44 | 7.63 | 7.41 | 8.05 | 8.53 | 8.25 | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| Sonora | 8.01 | 9.16 | 8.96 | 9.72 | 7.85 | 9.45 | 9.43 | 9.38 | 0.13 | 0.27 |

| Tabasco | 6.71 | 8.40 | 8.35 | 9.27 | 9.44 | 9.97 | 10.06 | 9.61 | 0.40 | 0.00 |

| Tamaulipas | 12.08 | 11.29 | 10.10 | 11.57 | 11.63 | 10.84 | 10.11 | 11.87 | -0.06 | 0.65 |

| Tlaxcala | 10.18 | 10.58 | 10.79 | 10.78 | 12.41 | 11.55 | 12.03 | 12.67 | 0.34 | 0.00 |

| Veracruz | 16.33 | 16.66 | 16.85 | 19.03 | 18.13 | 20.79 | 20.85 | 21.29 | 0.79 | 0.00 |

| Yucatán | 26.33 | 25.75 | 28.20 | 29.10 | 30.58 | 29.45 | 32.21 | 30.63 | 0.81 | 0.00 |

| Zacatecas | 4.69 | 5.40 | 5.32 | 5.02 | 5.67 | 6.00 | 7.23 | 6.22 | 0.68 | 0.01 |

| National | 10.52 | 10.69 | 10.89 | 11.16 | 11.01 | 11.64 | 11.29 | 11.97 | 0.18 | 0.00 |

Mortality rate due to malignant tumors of the liver for each state and for the nation for 2000-2007.

| State/year | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | Rate | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguascalientes | 4.03 | 3.54 | 3.95 | 3.00 | 3.22 | 2.81 | 3.58 | 3.43 | -0.09 | 0.22 |

| Baja California | 2.80 | 2.39 | 2.97 | 3.55 | 3.23 | 3.29 | 3.40 | 3.12 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| Baja California Sur | 2.09 | 2.27 | 4.22 | 3.04 | 4.24 | 2.75 | 4.77 | 3.91 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| Campeche | 3.87 | 4.45 | 3.96 | 2.84 | 4.68 | 4.35 | 3.51 | 4.76 | 0.05 | 0.63 |

| Chiapas | 4.02 | 4.10 | 4.52 | 4.27 | 4.14 | 4.41 | 3.89 | 4.31 | 0.11 | 0.01 |

| Chihuahua | 4.53 | 3.35 | 3.66 | 4.14 | 4.43 | 4.04 | 5.71 | 3.25 | -0.02 | 0.67 |

| Coahuila | 4.56 | 4.89 | 5.00 | 5.28 | 5.37 | 5.17 | 5.16 | 5.55 | 0.01 | 0.86 |

| Colima | 3.66 | 3.58 | 3.51 | 3.61 | 3.43 | 3.68 | 4.04 | 3.04 | 0.05 | 0.71 |

| Distrito Federal | 6.35 | 6.12 | 6.34 | 7.25 | 6.93 | 6.79 | 5.89 | 5.39 | -0.08 | 0.42 |

| Durango | 4.06 | 3.71 | 3.37 | 3.16 | 4.30 | 3.74 | 3.72 | 4.23 | 0.04 | 0.54 |

| Estado de México | 3.34 | 2.84 | 2.98 | 3.56 | 3.12 | 2.96 | 3.86 | 3.08 | 0.15 | 0.00 |

| Guanajuato | 3.18 | 2.61 | 3.19 | 3.56 | 3.73 | 3.61 | 3.65 | 3.87 | 0.03 | 0.58 |

| Guerrero | 3.26 | 4.14 | 4.91 | 5.75 | 4.51 | 5.57 | 5.33 | 5.55 | 0.14 | 0.01 |

| Hidalgo | 3.73 | 3.79 | 3.80 | 3.97 | 4.08 | 3.74 | 3.97 | 3.81 | 0.27 | 0.03 |

| Jalisco | 2.58 | 2.73 | 2.66 | 2.88 | 2.70 | 3.18 | 3.67 | 3.53 | 0.02 | 0.45 |

| Michoacán | 4.02 | 4.18 | 4.15 | 4.00 | 4.61 | 4.23 | 4.72 | 4.21 | 0.06 | 0.16 |

| Morelos | 4.04 | 3.59 | 3.73 | 3.82 | 3.96 | 4.13 | 4.59 | 5.22 | 0.17 | 0.02 |

| Nayarit | 6.36 | 5.46 | 5.73 | 5.37 | 6.77 | 6.57 | 7.49 | 5.08 | 0.06 | 0.67 |

| Nuevo León | 4.07 | 4.02 | 3.92 | 3.63 | 3.33 | 4.41 | 4.63 | 3.83 | 0.03 | 0.67 |

| Oaxaca | 4.54 | 4.28 | 5.08 | 5.26 | 5.31 | 4.87 | 5.71 | 6.42 | 0.24 | 0.01 |

| Puebla | 3.58 | 3.65 | 4.00 | 2.99 | 4.12 | 4.96 | 4.87 | 4.19 | 0.17 | 0.09 |

| Querétaro | 2.86 | 2.52 | 2.47 | 2.96 | 2.58 | 3.63 | 4.05 | 3.25 | 0.16 | 0.06 |

| Quintana Roo | 1.81 | 2.39 | 2.39 | 2.20 | 2.21 | 2.30 | 2.04 | 1.97 | -0.01 | 0.77 |

| San Luis Potosí | 4.84 | 4.29 | 4.38 | 5.32 | 6.79 | 5.50 | 5.72 | 6.87 | 0.31 | 0.02 |

| Sinaloa | 5.02 | 3.62 | 4.20 | 4.19 | 5.01 | 4.71 | 4.62 | 3.59 | -0.03 | 0.75 |

| Sonora | 3.50 | 4.21 | 3.72 | 4.57 | 3.60 | 3.98 | 3.61 | 2.92 | -0.09 | 0.29 |

| Tabasco | 4.44 | 4.76 | 5.17 | 4.68 | 4.99 | 4.69 | 5.90 | 5.13 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Tamaulipas | 5.64 | 6.35 | 6.65 | 6.10 | 5.82 | 5.50 | 6.60 | 5.33 | -0.06 | 0.52 |

| Tlaxcala | 2.36 | 2.32 | 3.47 | 3.89 | 3.34 | 1.96 | 4.59 | 3.44 | 0.17 | 0.26 |

| Veracruz | 6.47 | 6.67 | 7.43 | 7.46 | 8.13 | 8.50 | 8.46 | 7.87 | 0.27 | 0.01 |

| Yucatán | 7.66 | 6.76 | 6.84 | 7.96 | 7.40 | 7.06 | 6.21 | 7.26 | -0.07 | 0.49 |

| Zacatecas | 3.46 | 4.68 | 4.67 | 4.38 | 4.81 | 3.90 | 4.27 | 3.69 | -0.03 | 0.75 |

| National | 4.20 | 4.10 | 4.35 | 4.48 | 4.49 | 4.65 | 4.85 | 4.53 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

States with major mortality trends in Mexico. Each map represents the behavior of one of the pathologies: A. Viral hepatitis. B. Liver tumors. C. alcoholic liver disease. D. cirrhosis. The black states are the 10 states with the highest overall mortality rate. The gray states are the next 10 states and the white ones are the states with the lowest rates.

Several previous studies have predicted that the incidence of liver-related diseases and mortality will increase in the future.2,13,14 Our results confirm these predictions.

It is noteworthy that alcohol-related mortality is decreasing, although alcohol intake is still high.

The 2006 National Health Survey in Mexico showed that even though dependency on alcohol has decreased, it is still a major health issue.15 Alcohol-related deaths occur in different ways: they may be related to accidents, violence, or metabolic alterations. Although the first two causes may be acute, the third type, metabolic alterations, represents a chronic progression that will eventually result in death. Alcohol intake is rarely measured; therefore, statistics are limited to data obtained from patients or physicians. Alcohol consumption is sometimes considered consuetudinary when there are no metabolic alterations or symptoms. This, and the fact that many people usually do not consult a physician until damage is well established, results in underestimation of the incidence of alcohol-related disease.16 According to the National Survey of Addictions of 2008, 27 million people consume alcohol and at least 4 million people abuse it.15 In agreement with previous reports, we found that mortality associated with alcohol consumption (and alcoholic liver disease) was high.

It is noteworthy that reported cases of alcohol abuse among women are few. It is well established that in the past women consumed less alcohol than men and were less likely to abuse alcohol, although ages at which alcohol was consumed and the years of consumption were similar for both sexes.17 However, a recent study reported that 13-33% of alcohol abusers are women and that the incidence of alco-hol abuse among women has increased worldwide.18 Therefore, we would have expected a greater incidence of mortality associated with alcohol consumption in women; the known number of female cases is probably an underestimate of the real incidence of this disease among women.

Alcohol consumption, HCV infection, and cirrhosis may co-contribute to liver disease-related mortality. Some of the cases in which cirrhosis was reported as the cause of death may have been secondary to alcohol abuse or HCV infection. Fifty percent of cirrhotic deaths are related to alcohol18 and 20% are related to HCV infection.19

The 2008 National Survey of Addictions in Mexico showed that the alcohol abuse problem is concentrated in the central states and some of the northern states. Our study revealed a similar situation. We also found that in the Yucatán peninsula, Yucatán had the greatest alcohol-related mortality rate.15 In agreement with findings of the National Survey of Addictions that the Distrito Federal and the Estado de México had low or moderate alcohol consumption, we found that these states had better mortality trends than other states. Nevertheless, the overall rate of mortality was still very high, at least in the capital. Therefore, although the rate has decreased, alcohol consumption is still a major health issue in this country and requires attention.

The prevalence of HCV in Mexico is 1.6%, meaning that about 700,000 people are infected.20 The prevalence of HBV infection is 1.4% (measured using the HBVc-Ab)21 and 0.1-0.47% if the HBVs-Ag is considered.22 Some authors have reported that 9-33% of HCV-infected people are also infected with HBV.23 Even though we observed that the mortality due to viral infections was low, it is notable that the increase in mortality was mainly due to women. The low mortality rate may be because HBV and HCV tend to produce chronic and progressive states that eventually result in cirrhosis and hepatocellu-lar carcinoma (HCC) in 1-4% of cases, which can lead to death.24

Some studies have found that the incidence of several viral infections, including HIV and Hepatitis A, B, and, C, has increased along the border between the US and Mexico, most likely because of the increase in the size of the population in that re-gion.25 For this reason, a joint surveillance program has been implemented to reinforce health conditions in that zone.26 As expected, we observed a high mortality trend in the northern region.

Liver cirrhosis is closely associated with alcohol intake and infection with HCV or HBV. Alcohol is considered the main cause of cirrhosis and 20-30% of HCV-infected patients develop cirrhosis.13 Recent statistics show that this pathological state is the third most common cause of death in Mexico.1 As the incidences of viral infection-and alcohol-related mortality have increased, it was expected that the incidence of cirrhosis would increase. Bossetti et al. analyzed worldwide cirrhosis mortality rates from 1970 to 2005 and their findings are in agreement with our findings for both men and women.27 They concluded that mortality from cirrhosis was high in

Mexico but was decreasing in 1995. Our data show that it has increased since 2000; this may be due to better diagnostic methods or better surveillance methods.

The temporal change in this entity is very important. Narro Robles and colleagues performed a study on mortality trends in Mexico by state from 1970 to 1986. In that period, most reported deaths were concentrated in the central region of the country (Distrito Federal, Hidalgo, and Tlaxcala in the 1970s and Hidalgo, Tlaxcala, and the Estado de México in the 1980s).28 However, our study detected an increa-se in mortality in the northern and southern states and a decrease in central regions such as Distrito Federal and Hidalgo.

With regard to liver tumors, it is important to note that the most common primary liver cancer is HCC. Its incidence has a great impact worldwide and it is considered the fifth most common cancer in men and the eighth most common cancer in women. It is also considered the third and sixth most common cause of cancer-related death in men and women, respectively. Its incidence and mortality are higher in developing countries than in developed countries29 and it accounts for 5.6% of all human cancers, 7.5% of cancers in men, and 3.5% of cancers in women.14 The main etiology is HBV infection (55% of cases are secondary to HBV); the remainder of cases are caused by HCV and other factors such as diet.30

A previous study performed by our group found a similar increase after analyzing trends in mortality due to liver cancer from 2000 to 2006.14 The increase was greater than in the present study, but this is secondary to the fact that in 2007 there was a decrease in mortality compared with 2006. At the time of the previous study, cirrhosis mortality was expected to continue to increase; this study confir-

ms those results and reiterates the tendency to increase.

It is important to note that the central and southern regions of the country had the greatest decease in mortality due to liver tumors. Unfortunately there are no studies in which the incidence, prevalence or mortality of liver tumors have been analyzed for each state for comparison with our results. Nevertheless, we can see that mortality due to these tumors is closely related to states with an also high mortality of cirrhosis or alcohol. It is to consider that the main cause of HCC is precisely these two entities. In addition, it is convenient to remember that both of them are related to the progression of this liver cancer in the substrates of infection with hepatitis B and C virus and diabetes.31

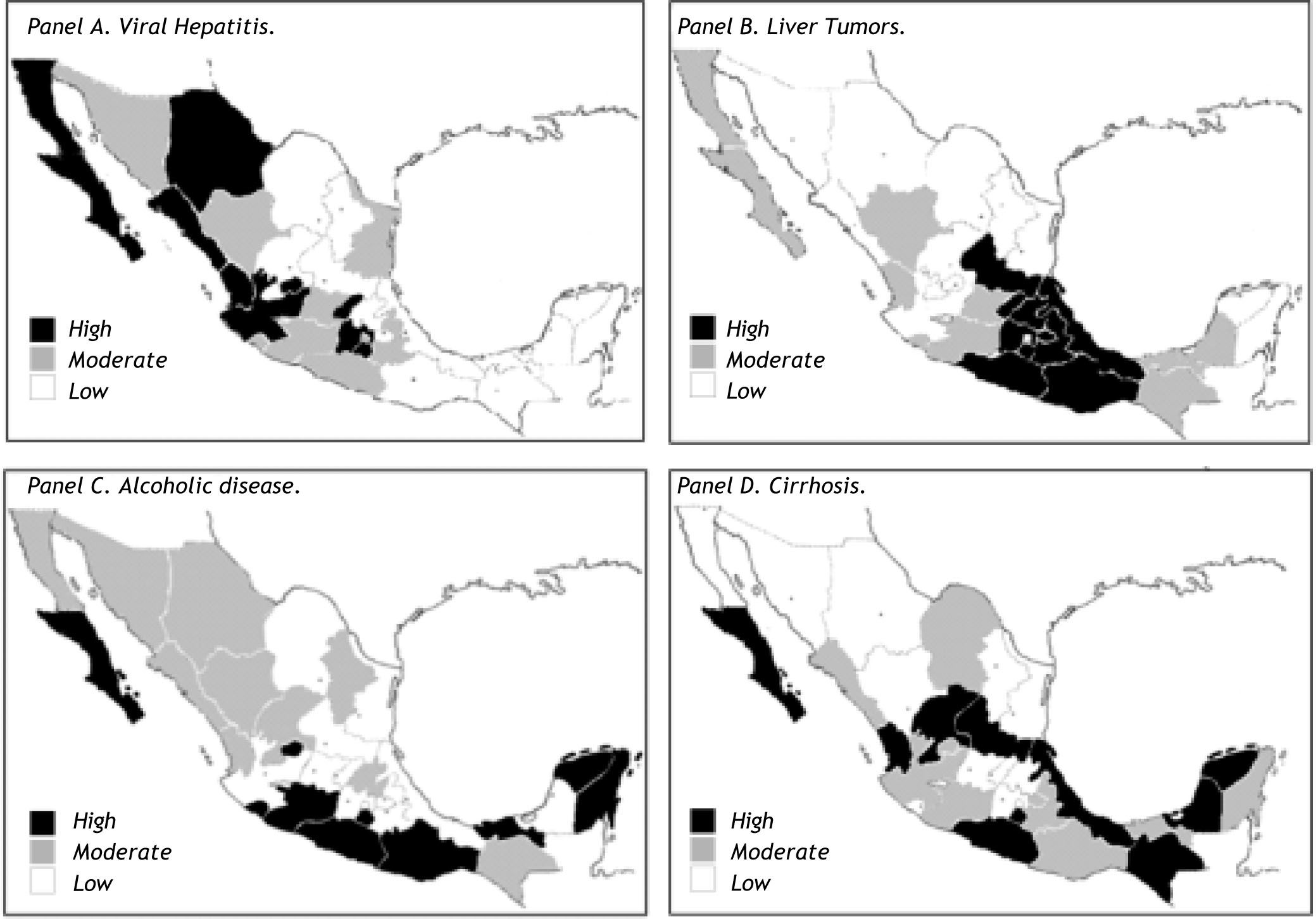

Although mortality associated with liver disease is high in Mexico and has a strong impact on public health, the main focus should be on states in which the incidence of liver disease-associated mortality has increased over time. Figure 7 shows the states with the highest increase according to pathology over the study period.

States with major increase in each pathology. Each map represents the behavior of one of the pathologies: A. Viral hepatitis. B. Liver tumors. C. Alcoholic liver disease. D. Cirrhosis. The black states have the highest increase, the gray states have a lower increase and the white states have the lowest increase. They are independent of the actual rate of overall mortality.

Even though several advances have been made in the pathophysiology and treatment of liver disease, liver-related mortality has increased significantly at the provincial and national levels and it is estimated that it will continue to increase. Most of the mortality is due to alcohol; nevertheless, the incidence of mortality due to cirrhosis, whether alcoholic or nonalcoholic, is catching up to that due to alcohol. It was previously believed that cirrhosis was a nonreversible state; however, some studies have demonstrated that not only can this entity be prevented, it can even be reverted.32 This is why we suggest preventative and opportune detection campaigns to diminish the alarming numbers of mortalities associated with liver diseases in the past decade.