Epidemiological data have shown that the prevalence of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema in children is still increasing, namely in Africa. However, there are no epidemiological studies on asthma or allergic diseases in Angolan children.

ObjectiveTo study the prevalence of asthma and other allergic diseases in Angolan children.

MethodsDescriptive, observational, cross-sectional study, using the ISAAC study methodology, in the province of Luanda, Angola in 6–7-year-old children. Forty-six (8.3%) public schools were randomly selected. Data were analysed using the SPSS Statistics version 24.0 software.

ResultsA total of 3080 children were studied. Results showed that the prevalence of asthma (wheezing in the previous 12 months) was 15.8%, that of rhinitis (sneezing, runny or blocked nose in the previous 12 months) was 19%, and that of eczema (itchy skin lesions in the previous 12 months) was 22%, without differences between sexes. Rhinitis was associated with a higher number of episodes of wheezing episodes, disturbed sleep and night cough, in children with asthma. Rhinitis, eczema, Split-type air conditioning system, antibiotic intake in the child's first year of life, frequent intake (more than once per month) of paracetamol and active maternal smoking were associated with a higher risk of having asthma, whereas electrical cooking was associated with a protective effect.

ConclusionAsthma and allergic diseases are highly prevalent in children from Luanda. A strategy for preventive and control measures should be implemented.

Asthma is associated with a relevant burden of disease worldwide, which may still be increasing.1,2 The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), part of which included two phases (Phases I and III) separated by a 5–10-year interval, was implemented in multiple centres worldwide. Although there were differences in prevalence values of asthma, rhinitis and eczema among participating countries, prevalence was increasing in children, particularly in countries with a lower prevalence in Phase I, and which mostly included developing countries.3,4

Epidemiological data regarding children from Africa are scarce but global analysis of the ISAAC study and other reports showed that the prevalence of asthma averaged around 10% for 6–7-year olds.2,5 Furthermore, prevalence values for asthma varied significantly throughout Africa: 16% in Botswana,6 13.3% in Mozambique,7 11.1% in South Africa,8 9% in Senegal,9 and 4.8% in Nigeria.3 In addition, increases in prevalence were detected between Phases I and III, as reported in Nigeria, with values increasing from 4.8% to 5.6%.3,10 Furthermore, African countries had a high proportion of children reporting symptoms of severe asthma.2,11 In Angola, asthma is one of the main causes for visits to emergency units in children. However, although we have previously studied the prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases in Angolan adolescents,12 no studies were performed in children. We therefore decided to study the prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases in 6–7-year-old children from Luanda.

MethodsPopulation sampleCross-sectional, observational study performed in the province of Luanda, Angola, between August and October 2014, and between March and May 2015, in 6–7-year-old schoolchildren. Luanda is the capital and includes seven boroughs in which 97.5% of the population is urban. In Luanda, 46 (8.3%) primary public schools were randomly selected out of a total of 552, to meet the ISAAC criterium of analysing at least 3000 children.13 Children's parents/guardians were classified, in sociodemographic terms, as low, middle or upper class, in accordance with criteria of the Angolan 2015–2016 IIMS Inquiry on Multiple and Health Indicators.

Written questionnairesWe used the Portuguese version of the ISAAC questionnaire,13,14 which has questions on symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinitis and eczema and which was filled out by children's parents/guardians. The ISAAC Phase III Environmental exposure and risk factor questionnaire was also used.15 All questions and explanations about the questionnaire were supplied in a standardised manner, in Portuguese.

Current asthma was defined as positive replies to the question “Has your child had wheezing or whistling in the chest in the past 12 months?”.13 Parents also answered questions on the number of wheezing episodes, interference of wheezing with sleep or speech, relation to physical exercise and episodes of nocturnal cough, in the previous 12 months.

Current rhinitis was defined as sneezing bouts, rhinorrhoea or nasal obstruction, in the absence of flu, in the previous 12 months, and rhinoconjunctivitis involved the presence of rhinitis and conjunctivitis symptoms.13 Parents were also asked whether nasal symptoms interfered with their child's daily activities and whether their child had ever had “hay fever”.

Eczema was considered if parents/guardians reported cutaneous lesions with pruritus, which waxed and waned, in the previous 12 months.13 Additional questions were asked regarding specific location and age of appearance of the lesions and whether the latter interfered with sleep.

The questionnaire on environmental exposure included questions on the type of fuel used for cooking, type of indoor home-cooling device, frequency of passage of trucks in front of their homes, presence of cats and dogs at home, child's passive exposure to tobacco smoke, use of antibiotics in their child's first year of life, frequency of use of paracetamol, breastfeeding and the number of siblings living in the home.

Measurement of lung function by peak flow metrePeak flow metre recordings (Mini-Wright Peak Flow Metre, Clement-Clarke, Harlow, UK) were performed in all children with reported current asthma. Children with symptoms of infectious acute respiratory illness were excluded. Readings were taken in triplicate with the child standing and the highest value was recorded only if the coefficient of variation was below 5%. Since there are no reference values for Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF) for Angolan children, we used values from Nigerian schoolchildren16 for the calculation of percentage predicted values and comparison with ranges of reference values (above 80%, 50–80% or below 50%). We defined confirmed current asthma as current asthma symptoms associated with PEF values below 80% predicted.

Height and weight measurementsThe height of each child was measured using a portable 200cm stadiometer, accurate to 0.1cm (SECA 123, Hamburg, Germany) and recorded in centimetres. Children had their backs turned to the stadiometer and their heads were positioned in the Frankfurt horizontal plane. Weight was measured using a portable, calibrated scales, with a 150kg capacity and a 0.1kg precision (SECA 780 digital scale, Hamburg, Germany) and recorded in kilograms. For both measurements, children were standing upright, and barefoot.

Calculation of body mass index (BMI)Body mass index (BMI) was calculated with the standard formula: weight (in kg)/height (in m2). Since there are no BMI reference values for Angola, children were classified as “underweight”, “normal weight”, “overweight”, and “obese”, in accordance with World Health Organisation definitions regarding BMI values.17

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Angolan Ministry of Health and the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Beira Interior, Portugal, by the Provincial Board of Education, Luanda, Angola, and by the Directors of the selected schools. All parents/guardians were informed about the study in a face-to-face session as well as via a leaflet, and those who agreed to participate signed a written consent form.

Statistical analysisData were analysed using the Software Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0®. Descriptive analysis was used for frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations. Prevalence values were estimated by dividing the number of positive responses to the questions selected for diagnosis by the number of completed questionnaires. Comparison of proportions was performed using Chi-Square Test or Fisher's Exact Test, as appropriate. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated for characterisation of possible risk factors for asthma. A logistic regression model was developed using the logit function. For categorical variables, the “normal” situation was defined as the reference category and odds were estimated for the other categories against the reference one. Quality and assumptions of the model were tested using the Omnibus and Hosmer–Lemeshow tests, as well as by analysis of residuals and outliers. A Receptor Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis of the model was also carried out. A p-value of less than 0.05 was regarded as significant with all two-tailed statistical tests.

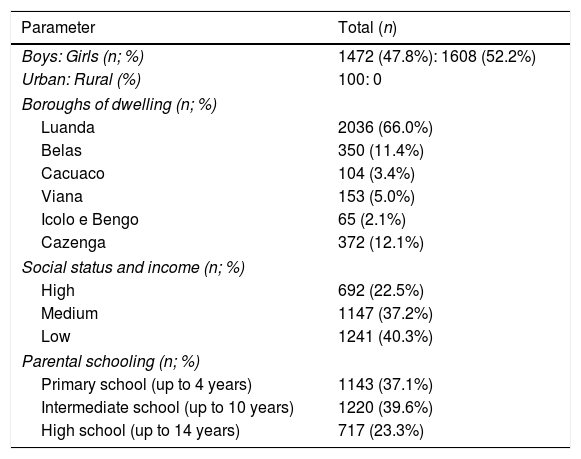

ResultsDemographicsAll directors of the 46 randomly selected schools agreed to participate in the study. The final sample included 4505 children whose parents received information and the questionnaire. From these, 83 parents did not return the questionnaire (98% reply rate), and 1342 questionnaires were excluded because they were incomplete or incorrectly filled in. Thus, we obtained 3080 valid questionnaires (68.3% reply rate). There was no concentration of non-responders or responders with invalidated questionnaires in any specific school. Of the validated 3080 questionnaires, 1608 (52.2%) were female and 1472 were male (47.7%) (Table 1). Gender and age distributions were similar to those in the non-responders or responders with invalid questionnaires. All children who participated in the study lived in an urban area. The borough of Kissama was excluded because most parents/guardians were illiterate. In socio-demographic terms, just over 40% of the children (1241) belonged to a low social class, whereas most belonged to middle or upper classes. Although only around 23% of the mothers had high school/university level schooling, significant proportions had lower secondary or primary schooling.

Sociodemographic data of study sample of 6–7-year-old children from Luanda.

| Parameter | Total (n) |

|---|---|

| Boys: Girls (n; %) | 1472 (47.8%): 1608 (52.2%) |

| Urban: Rural (%) | 100: 0 |

| Boroughs of dwelling (n; %) | |

| Luanda | 2036 (66.0%) |

| Belas | 350 (11.4%) |

| Cacuaco | 104 (3.4%) |

| Viana | 153 (5.0%) |

| Icolo e Bengo | 65 (2.1%) |

| Cazenga | 372 (12.1%) |

| Social status and income (n; %) | |

| High | 692 (22.5%) |

| Medium | 1147 (37.2%) |

| Low | 1241 (40.3%) |

| Parental schooling (n; %) | |

| Primary school (up to 4 years) | 1143 (37.1%) |

| Intermediate school (up to 10 years) | 1220 (39.6%) |

| High school (up to 14 years) | 717 (23.3%) |

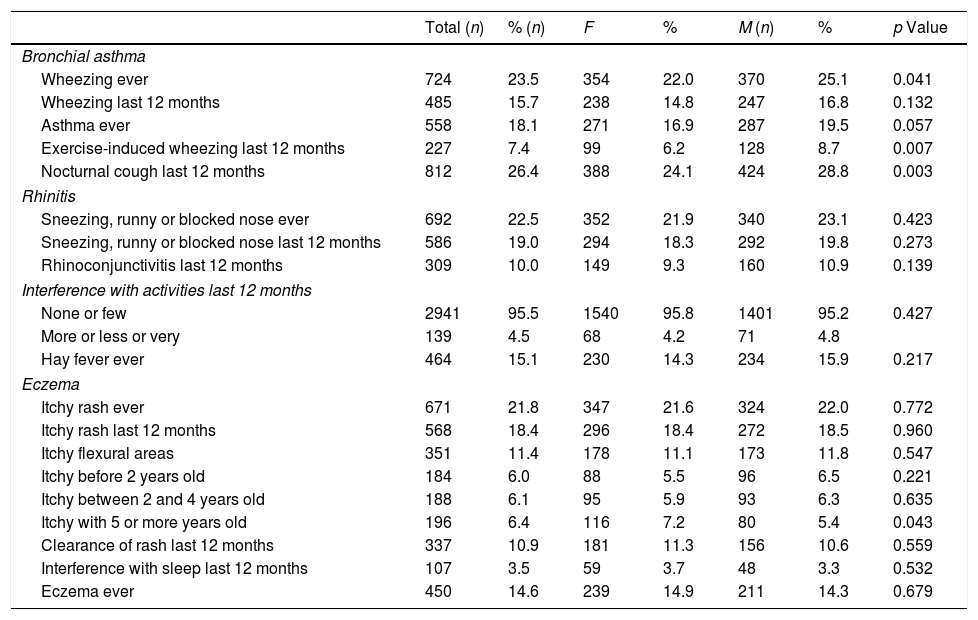

Of the 3080 children included in the study, almost 24% reported that they had already had wheezing episodes in their lives (Table 2). However, 485 children had had wheezing in the last 12 months, indicating a prevalence of current asthma of 15.8% (95% CI: 14.5–17.1%), without significant differences between boys and girls. Only around 7% of the children reported having wheezing during or after physical exercise, but 26.4% reported episodes of nocturnal dry cough, not associated with respiratory infections in the previous 12 months (Table 2).

Prevalence rates for asthma, rhinitis and eczema.

| Total (n) | % (n) | F | % | M (n) | % | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bronchial asthma | |||||||

| Wheezing ever | 724 | 23.5 | 354 | 22.0 | 370 | 25.1 | 0.041 |

| Wheezing last 12 months | 485 | 15.7 | 238 | 14.8 | 247 | 16.8 | 0.132 |

| Asthma ever | 558 | 18.1 | 271 | 16.9 | 287 | 19.5 | 0.057 |

| Exercise-induced wheezing last 12 months | 227 | 7.4 | 99 | 6.2 | 128 | 8.7 | 0.007 |

| Nocturnal cough last 12 months | 812 | 26.4 | 388 | 24.1 | 424 | 28.8 | 0.003 |

| Rhinitis | |||||||

| Sneezing, runny or blocked nose ever | 692 | 22.5 | 352 | 21.9 | 340 | 23.1 | 0.423 |

| Sneezing, runny or blocked nose last 12 months | 586 | 19.0 | 294 | 18.3 | 292 | 19.8 | 0.273 |

| Rhinoconjunctivitis last 12 months | 309 | 10.0 | 149 | 9.3 | 160 | 10.9 | 0.139 |

| Interference with activities last 12 months | |||||||

| None or few | 2941 | 95.5 | 1540 | 95.8 | 1401 | 95.2 | 0.427 |

| More or less or very | 139 | 4.5 | 68 | 4.2 | 71 | 4.8 | |

| Hay fever ever | 464 | 15.1 | 230 | 14.3 | 234 | 15.9 | 0.217 |

| Eczema | |||||||

| Itchy rash ever | 671 | 21.8 | 347 | 21.6 | 324 | 22.0 | 0.772 |

| Itchy rash last 12 months | 568 | 18.4 | 296 | 18.4 | 272 | 18.5 | 0.960 |

| Itchy flexural areas | 351 | 11.4 | 178 | 11.1 | 173 | 11.8 | 0.547 |

| Itchy before 2 years old | 184 | 6.0 | 88 | 5.5 | 96 | 6.5 | 0.221 |

| Itchy between 2 and 4 years old | 188 | 6.1 | 95 | 5.9 | 93 | 6.3 | 0.635 |

| Itchy with 5 or more years old | 196 | 6.4 | 116 | 7.2 | 80 | 5.4 | 0.043 |

| Clearance of rash last 12 months | 337 | 10.9 | 181 | 11.3 | 156 | 10.6 | 0.559 |

| Interference with sleep last 12 months | 107 | 3.5 | 59 | 3.7 | 48 | 3.3 | 0.532 |

| Eczema ever | 450 | 14.6 | 239 | 14.9 | 211 | 14.3 | 0.679 |

The prevalence of “Wheezing ever”, “Wheezing with physical exercise in the last 12 months” and “Nocturnal cough in the last 12 months” was significantly higher in girls than in boys.

Of the 485 children with current asthma, only 37 (8.6%) were regularly seen by a paediatrician due to their asthma symptoms, and 268 (55.2%) had already been seen more than once at an emergency department and occasionally prescribed a β2-agonist.

Prevalence of rhinitisThe prevalence of current rhinitis was 19% (95% CI: 17.7–20.5%; n=586), and that of current rhinoconjunctivitis was 10% (95% CI: 9.0–11.1%; n=309) (Table 2). Symptoms of rhinitis interfered with the daily activities in only 4.5% of the children. Around 15% of the children had had “Hay fever ever”. No significant differences in the prevalence of rhinitis or rhinoconjunctivitis symptoms were seen between sexes.

Prevalence of eczemaItchy rash or eczema “ever” were reported in almost 22% of the children (Table 2), and 18.4% of the children (95% CI: 17.0–19.8%; n=568) had had such lesions in the previous 12 months. The lesions affected specific areas of the body in 11.4% of the children and disappeared at least temporarily, in around 11% of the cases. Cutaneous symptoms only affected sleep in 3.5% of the children. No significant differences in the prevalence of eczema symptoms were seen between sexes.

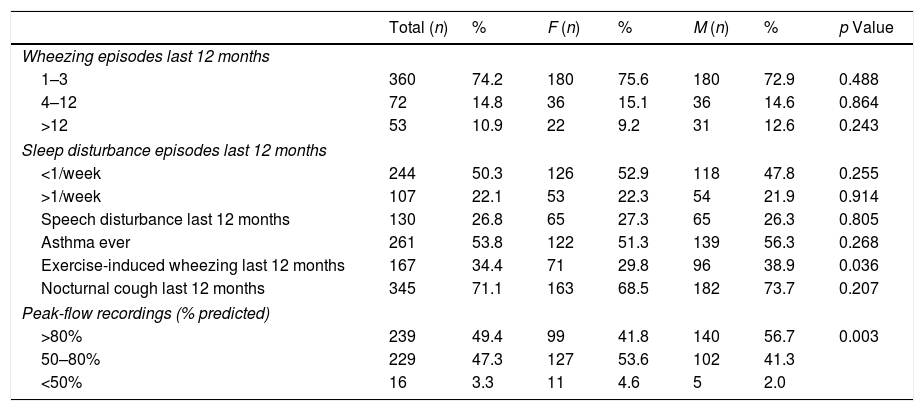

Respiratory symptoms and function in adolescents with current asthmaOf the 485 children with reported current asthma, most (74.2%) had only had one to three wheezing episodes (Table 3). However, almost 11% reported more than 12 episodes and 22.1% of the children woke up during the night, more than once weekly, because of wheezing episodes. In addition, almost 27% of the children had had episodes of wheezing that interfered with speech, 34% had had wheezing episodes during or after physical exercise, and 71% reported dry cough during the night. Finally, PEF recordings showed that a high proportion (47.3%; 229) of the children had a moderate degree of obstruction and around 3% (16 children) had severe obstruction (Table 3), confirming the presence of asthma in 50% of the children reporting symptoms in the previous 12 months, and suggesting a prevalence of confirmed current asthma of 8.0% (95% CI: 7.0–9.0%).

Clinical features of asthma in children with asthma symptoms (“Wheezing in the last 12 months”; n=485).

| Total (n) | % | F (n) | % | M (n) | % | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheezing episodes last 12 months | |||||||

| 1–3 | 360 | 74.2 | 180 | 75.6 | 180 | 72.9 | 0.488 |

| 4–12 | 72 | 14.8 | 36 | 15.1 | 36 | 14.6 | 0.864 |

| >12 | 53 | 10.9 | 22 | 9.2 | 31 | 12.6 | 0.243 |

| Sleep disturbance episodes last 12 months | |||||||

| <1/week | 244 | 50.3 | 126 | 52.9 | 118 | 47.8 | 0.255 |

| >1/week | 107 | 22.1 | 53 | 22.3 | 54 | 21.9 | 0.914 |

| Speech disturbance last 12 months | 130 | 26.8 | 65 | 27.3 | 65 | 26.3 | 0.805 |

| Asthma ever | 261 | 53.8 | 122 | 51.3 | 139 | 56.3 | 0.268 |

| Exercise-induced wheezing last 12 months | 167 | 34.4 | 71 | 29.8 | 96 | 38.9 | 0.036 |

| Nocturnal cough last 12 months | 345 | 71.1 | 163 | 68.5 | 182 | 73.7 | 0.207 |

| Peak-flow recordings (% predicted) | |||||||

| >80% | 239 | 49.4 | 99 | 41.8 | 140 | 56.7 | 0.003 |

| 50–80% | 229 | 47.3 | 127 | 53.6 | 102 | 41.3 | |

| <50% | 16 | 3.3 | 11 | 4.6 | 5 | 2.0 | |

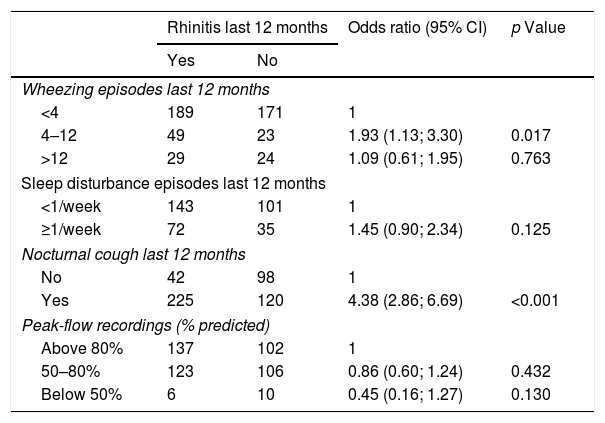

In the 485 children with current asthma, the presence of rhinitis in the last 12 months was significantly associated with a higher number of episodes of nocturnal cough (p<0.001; Table 4). In fact, having current rhinitis symptoms increased the risk of having a high number of wheezing episodes, disturbed sleep, and nocturnal episodes of dry cough about four-fold (Odds ratio).

Associations between the presence of rhinitis in the last 12 months and clinical asthma parameters in children with asthma symptoms (wheezing episodes in the last 12 months; n=485).

| Rhinitis last 12 months | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Wheezing episodes last 12 months | ||||

| <4 | 189 | 171 | 1 | |

| 4–12 | 49 | 23 | 1.93 (1.13; 3.30) | 0.017 |

| >12 | 29 | 24 | 1.09 (0.61; 1.95) | 0.763 |

| Sleep disturbance episodes last 12 months | ||||

| <1/week | 143 | 101 | 1 | |

| ≥1/week | 72 | 35 | 1.45 (0.90; 2.34) | 0.125 |

| Nocturnal cough last 12 months | ||||

| No | 42 | 98 | 1 | |

| Yes | 225 | 120 | 4.38 (2.86; 6.69) | <0.001 |

| Peak-flow recordings (% predicted) | ||||

| Above 80% | 137 | 102 | 1 | |

| 50–80% | 123 | 106 | 0.86 (0.60; 1.24) | 0.432 |

| Below 50% | 6 | 10 | 0.45 (0.16; 1.27) | 0.130 |

For each categorical variable, the “normal” situation was defined as the reference category and odds were estimated for the other categories against the reference one.

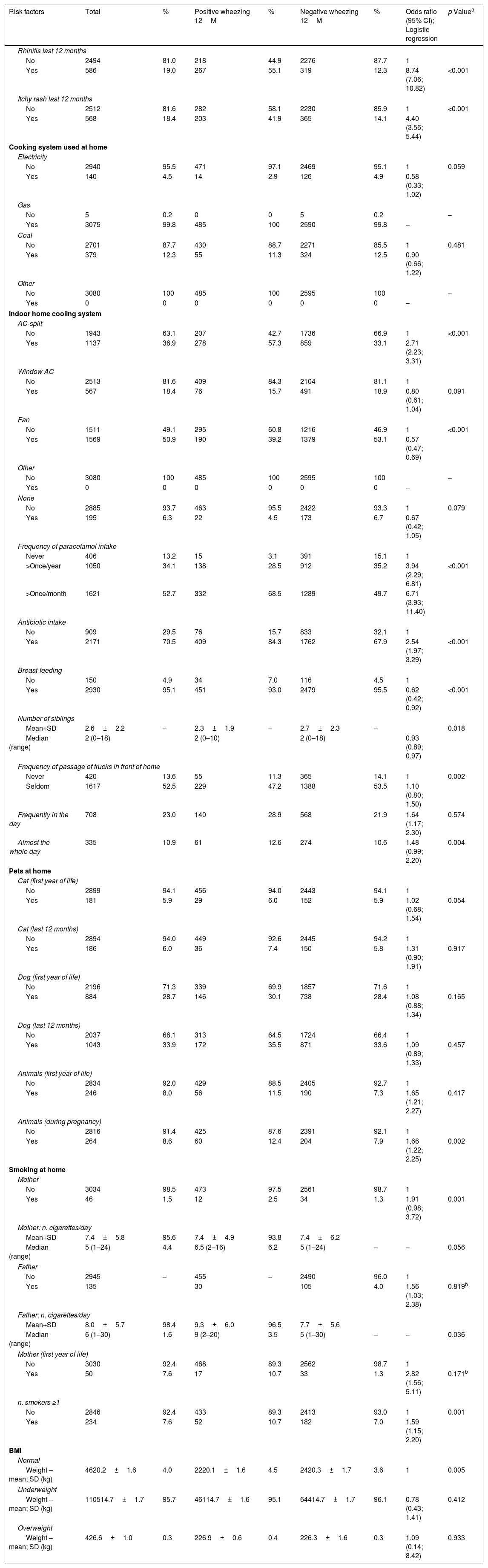

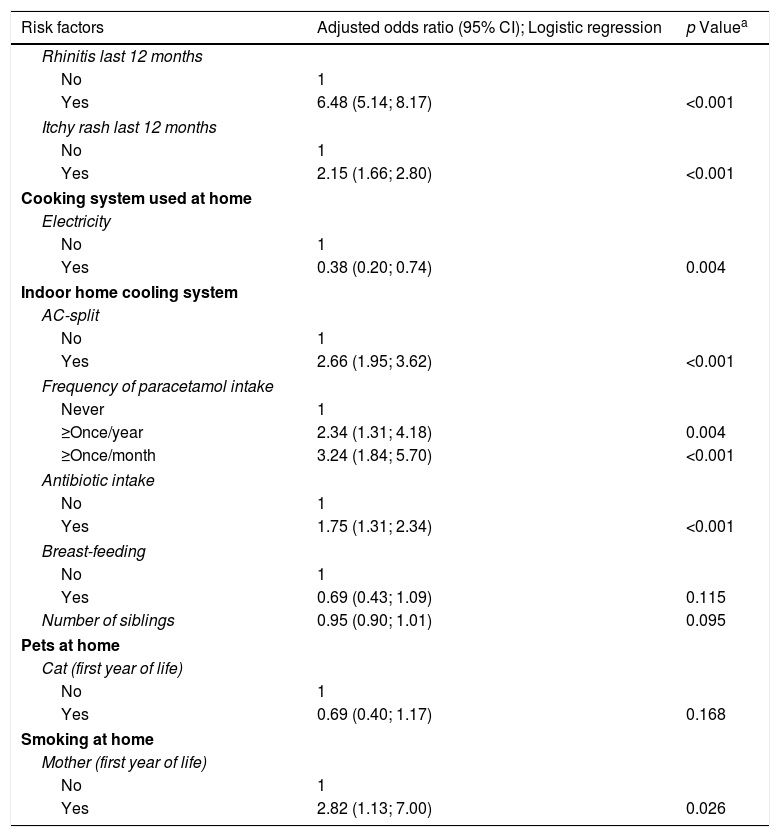

Current rhinitis or eczema, AC-split home cooling system, excessive intake of paracetamol, intake of antibiotics in the first year of life, frequent passage of trucks, the presence of animals at home during pregnancy or the child's first year of life, and active maternal smoking during the child's infancy as well as the number of smokers at home were significantly associated with asthma, using univariate analysis, whereas having a fan as a cooling system, having a higher number of siblings at home, and breastfeeding significantly reduced the risk of asthma, and using electricity for cooking was almost significantly protective (Table 5). However, in the logistic regression model, only rhinitis, eczema, AC-split type of cooling system, high intake of paracetamol, antibiotic intake and active maternal smoking during the child's first year of life were confirmed as significant risk factors, whereas electricity as cooking system was a protective factor (Table 6).

Risk factors for probable asthma (Wheezing last 12 months).

| Risk factors | Total | % | Positive wheezing 12M | % | Negative wheezing 12M | % | Odds ratio (95% CI); Logistic regression | p Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhinitis last 12 months | ||||||||

| No | 2494 | 81.0 | 218 | 44.9 | 2276 | 87.7 | 1 | |

| Yes | 586 | 19.0 | 267 | 55.1 | 319 | 12.3 | 8.74 (7.06; 10.82) | <0.001 |

| Itchy rash last 12 months | ||||||||

| No | 2512 | 81.6 | 282 | 58.1 | 2230 | 85.9 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 568 | 18.4 | 203 | 41.9 | 365 | 14.1 | 4.40 (3.56; 5.44) | |

| Cooking system used at home | ||||||||

| Electricity | ||||||||

| No | 2940 | 95.5 | 471 | 97.1 | 2469 | 95.1 | 1 | 0.059 |

| Yes | 140 | 4.5 | 14 | 2.9 | 126 | 4.9 | 0.58 (0.33; 1.02) | |

| Gas | ||||||||

| No | 5 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0.2 | – | |

| Yes | 3075 | 99.8 | 485 | 100 | 2590 | 99.8 | – | |

| Coal | ||||||||

| No | 2701 | 87.7 | 430 | 88.7 | 2271 | 85.5 | 1 | 0.481 |

| Yes | 379 | 12.3 | 55 | 11.3 | 324 | 12.5 | 0.90 (0.66; 1.22) | |

| Other | ||||||||

| No | 3080 | 100 | 485 | 100 | 2595 | 100 | – | |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | |

| Indoor home cooling system | ||||||||

| AC-split | ||||||||

| No | 1943 | 63.1 | 207 | 42.7 | 1736 | 66.9 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1137 | 36.9 | 278 | 57.3 | 859 | 33.1 | 2.71 (2.23; 3.31) | |

| Window AC | ||||||||

| No | 2513 | 81.6 | 409 | 84.3 | 2104 | 81.1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 567 | 18.4 | 76 | 15.7 | 491 | 18.9 | 0.80 (0.61; 1.04) | 0.091 |

| Fan | ||||||||

| No | 1511 | 49.1 | 295 | 60.8 | 1216 | 46.9 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1569 | 50.9 | 190 | 39.2 | 1379 | 53.1 | 0.57 (0.47; 0.69) | |

| Other | ||||||||

| No | 3080 | 100 | 485 | 100 | 2595 | 100 | – | |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | |

| None | ||||||||

| No | 2885 | 93.7 | 463 | 95.5 | 2422 | 93.3 | 1 | 0.079 |

| Yes | 195 | 6.3 | 22 | 4.5 | 173 | 6.7 | 0.67 (0.42; 1.05) | |

| Frequency of paracetamol intake | ||||||||

| Never | 406 | 13.2 | 15 | 3.1 | 391 | 15.1 | 1 | |

| >Once/year | 1050 | 34.1 | 138 | 28.5 | 912 | 35.2 | 3.94 (2.29; 6.81) | <0.001 |

| >Once/month | 1621 | 52.7 | 332 | 68.5 | 1289 | 49.7 | 6.71 (3.93; 11.40) | |

| Antibiotic intake | ||||||||

| No | 909 | 29.5 | 76 | 15.7 | 833 | 32.1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 2171 | 70.5 | 409 | 84.3 | 1762 | 67.9 | 2.54 (1.97; 3.29) | <0.001 |

| Breast-feeding | ||||||||

| No | 150 | 4.9 | 34 | 7.0 | 116 | 4.5 | 1 | |

| Yes | 2930 | 95.1 | 451 | 93.0 | 2479 | 95.5 | 0.62 (0.42; 0.92) | <0.001 |

| Number of siblings | ||||||||

| Mean+SD | 2.6±2.2 | – | 2.3±1.9 | – | 2.7±2.3 | – | 0.018 | |

| Median (range) | 2 (0–18) | 2 (0–10) | 2 (0–18) | 0.93 (0.89; 0.97) | ||||

| Frequency of passage of trucks in front of home | ||||||||

| Never | 420 | 13.6 | 55 | 11.3 | 365 | 14.1 | 1 | 0.002 |

| Seldom | 1617 | 52.5 | 229 | 47.2 | 1388 | 53.5 | 1.10 (0.80; 1.50) | |

| Frequently in the day | 708 | 23.0 | 140 | 28.9 | 568 | 21.9 | 1.64 (1.17; 2.30) | 0.574 |

| Almost the whole day | 335 | 10.9 | 61 | 12.6 | 274 | 10.6 | 1.48 (0.99; 2.20) | 0.004 |

| Pets at home | ||||||||

| Cat (first year of life) | ||||||||

| No | 2899 | 94.1 | 456 | 94.0 | 2443 | 94.1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 181 | 5.9 | 29 | 6.0 | 152 | 5.9 | 1.02 (0.68; 1.54) | 0.054 |

| Cat (last 12 months) | ||||||||

| No | 2894 | 94.0 | 449 | 92.6 | 2445 | 94.2 | 1 | |

| Yes | 186 | 6.0 | 36 | 7.4 | 150 | 5.8 | 1.31 (0.90; 1.91) | 0.917 |

| Dog (first year of life) | ||||||||

| No | 2196 | 71.3 | 339 | 69.9 | 1857 | 71.6 | 1 | |

| Yes | 884 | 28.7 | 146 | 30.1 | 738 | 28.4 | 1.08 (0.88; 1.34) | 0.165 |

| Dog (last 12 months) | ||||||||

| No | 2037 | 66.1 | 313 | 64.5 | 1724 | 66.4 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1043 | 33.9 | 172 | 35.5 | 871 | 33.6 | 1.09 (0.89; 1.33) | 0.457 |

| Animals (first year of life) | ||||||||

| No | 2834 | 92.0 | 429 | 88.5 | 2405 | 92.7 | 1 | |

| Yes | 246 | 8.0 | 56 | 11.5 | 190 | 7.3 | 1.65 (1.21; 2.27) | 0.417 |

| Animals (during pregnancy) | ||||||||

| No | 2816 | 91.4 | 425 | 87.6 | 2391 | 92.1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 264 | 8.6 | 60 | 12.4 | 204 | 7.9 | 1.66 (1.22; 2.25) | 0.002 |

| Smoking at home | ||||||||

| Mother | ||||||||

| No | 3034 | 98.5 | 473 | 97.5 | 2561 | 98.7 | 1 | |

| Yes | 46 | 1.5 | 12 | 2.5 | 34 | 1.3 | 1.91 (0.98; 3.72) | 0.001 |

| Mother: n. cigarettes/day | ||||||||

| Mean+SD | 7.4±5.8 | 95.6 | 7.4±4.9 | 93.8 | 7.4±6.2 | |||

| Median (range) | 5 (1–24) | 4.4 | 6.5 (2–16) | 6.2 | 5 (1–24) | – | – | 0.056 |

| Father | ||||||||

| No | 2945 | – | 455 | – | 2490 | 96.0 | 1 | |

| Yes | 135 | 30 | 105 | 4.0 | 1.56 (1.03; 2.38) | 0.819b | ||

| Father: n. cigarettes/day | ||||||||

| Mean+SD | 8.0±5.7 | 98.4 | 9.3±6.0 | 96.5 | 7.7±5.6 | |||

| Median (range) | 6 (1–30) | 1.6 | 9 (2–20) | 3.5 | 5 (1–30) | – | – | 0.036 |

| Mother (first year of life) | ||||||||

| No | 3030 | 92.4 | 468 | 89.3 | 2562 | 98.7 | 1 | |

| Yes | 50 | 7.6 | 17 | 10.7 | 33 | 1.3 | 2.82 (1.56; 5.11) | 0.171b |

| n. smokers ≥1 | ||||||||

| No | 2846 | 92.4 | 433 | 89.3 | 2413 | 93.0 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 234 | 7.6 | 52 | 10.7 | 182 | 7.0 | 1.59 (1.15; 2.20) | |

| BMI | ||||||||

| Normal | ||||||||

| Weight – mean; SD (kg) | 4620.2±1.6 | 4.0 | 2220.1±1.6 | 4.5 | 2420.3±1.7 | 3.6 | 1 | 0.005 |

| Underweight | ||||||||

| Weight – mean; SD (kg) | 110514.7±1.7 | 95.7 | 46114.7±1.6 | 95.1 | 64414.7±1.7 | 96.1 | 0.78 (0.43; 1.41) | 0.412 |

| Overweight | ||||||||

| Weight – mean; SD (kg) | 426.6±1.0 | 0.3 | 226.9±0.6 | 0.4 | 226.3±1.6 | 0.3 | 1.09 (0.14; 8.42) | 0.933 |

Adjusted odds ratios of risk factors for probable asthma (wheezing last 12 months).

| Risk factors | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI); Logistic regression | p Valuea |

|---|---|---|

| Rhinitis last 12 months | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 6.48 (5.14; 8.17) | <0.001 |

| Itchy rash last 12 months | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 2.15 (1.66; 2.80) | <0.001 |

| Cooking system used at home | ||

| Electricity | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.38 (0.20; 0.74) | 0.004 |

| Indoor home cooling system | ||

| AC-split | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 2.66 (1.95; 3.62) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of paracetamol intake | ||

| Never | 1 | |

| ≥Once/year | 2.34 (1.31; 4.18) | 0.004 |

| ≥Once/month | 3.24 (1.84; 5.70) | <0.001 |

| Antibiotic intake | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.75 (1.31; 2.34) | <0.001 |

| Breast-feeding | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.69 (0.43; 1.09) | 0.115 |

| Number of siblings | 0.95 (0.90; 1.01) | 0.095 |

| Pets at home | ||

| Cat (first year of life) | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.69 (0.40; 1.17) | 0.168 |

| Smoking at home | ||

| Mother (first year of life) | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 2.82 (1.13; 7.00) | 0.026 |

Wald's test; OR's adjusted for all factors in Table 5, except BMI and “n. of cigarettes/day father and mother”; Only the results are shown when p<0.2; Omnibus test: p<0.001; Hosmer–Lemeshow test: p=0.330; Nagelkerke pseudo-R2=0.303; ROC analysis: area under curve=0.809 (95%CI: (0.787; 0.831)); sensitivity=72.8%, specificity=76.1%, overall=75.6% (probability cut-off=0.148).

For each categorical variable, the “normal” situation was defined as the reference category and odds were estimated for the other categories against the reference one.

This is the first study of asthma prevalence in Angolan children, one of few studies in 6–7-year-olds in Africa, and showed a value of 15.8%, without significant differences between boys and girls, and that 8% of asthmatics had confirmed bronchial obstruction. The prevalence of rhinitis was 19%, that of eczema was 22%, again without differences between genders. Rhinitis was associated with clearly more symptomatic asthma. Rhinitis and eczema, use of AC-split home cooling system, frequent intake of paracetamol, antibiotic use and active maternal smoking in the child's first year of life were significantly associated with an increased risk of asthma, whereas cooking with electricity was protective.

We followed the ISAAC methodology in a random sample of more than 3000 children, had a high reply rate, and used “Wheezing episodes in the last 12 months” for the diagnosis of current asthma, since it has high sensitivity for this purpose.18,19 The prevalence of asthma in our study (15.8%) places Angola as the country with the 11th highest prevalence, when compared with countries that participated in ISAAC Phases I and III, and which showed Phase III values ranging between 37.6% (Costa Rica) and 4.1% (Indonesia).3 Furthermore, the prevalence value we found is higher than the mean for 6–7-year-old children in Africa (10%).11 The highest value was reported in a 2014/2015 study in Botswana (15.9%),6 which is similar to our report, although only 385 schoolchildren were included in the former study. In Mozambique, data from 2004 showed a relatively similar prevalence of asthma (13.3%).7 Prevalence was lower both in South Africa (11.1%),2,8 and in Nigeria (5.5%), in 2001/2002.3,10 Finally, a study using the ISAAC protocol, performed in rural Senegal showed a prevalence of 9.0% in 5–8-year-old schoolchildren.9 Since these studies used the same questionnaire, discrepant values mays be due to time, genetic, environmental or lifestyle differences, as was seen in Mozambique, with prevalence of cough being higher in suburban and semi-rural children.7 However, our study as well as others may have underestimated the prevalence of asthma, since some of the parents/guardians did not know the concept of “wheezing”, and symptom recognition may be poor or not well accepted.7 The prevalence of nocturnal cough in our study (26.4%) was high, but similar to that in Mozambique (27.5%),7 slightly above that seen in Botswana6 and Senegal,9 and clearly above that reported in Nigeria (6.5%).3 However, it is possible that cough was not always associated with asthma.

Although the prevalence of current rhinitis (22.5%) was high, that of current rhinoconjunctivitis was lower (10%), and places Angola at the bottom of the top third of ISAAC participating countries worldwide, above the global mean of 8.5%.3,20 In Africa, it was similar to prevalence in South Africa (10.6%)20 and Mozambique (8.9%)7 and much higher than in Nigeria (3.6%).3,20 In our study, only 15% of the parents/guardians reported that their children had “Hay fever ever”, which, again was similar to Mozambique (12%),7 and much lower than the value in Angolan (33%)12 or Mozambican adolescents.7 This suggests that either the prevalence of rhinoconjunctivitis tends to increase with age, or that adolescents more frequently overestimate the situation. Nevertheless, in non-English speaking countries, as well as in countries without a clear pollen season, as happens in Luanda, “hay fever” is a concept that is not easy to interpret.

The prevalence of current eczema in our study (18.4%) is the second highest in all ISAAC reporting countries, significantly higher than the mean world prevalence (9.3%).3,22 In Africa, it is much higher than the values reported in Mozambique (12.8%),7 South Africa (12.3%)21 and Nigeria (5%).3,21 In contrast with results in 13–14-year-old adolescents.3,10,12 the highest prevalences of eczema in the ISAAC study of 6–7-year olds came essentially from scattered centres, including the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Panama and Chile which also reported the highest asthma prevalences,10 and Angola has a similar situation. Although eczema is a significant public health problem in developing countries,21 non-eczema-related manifestations may have been reported in our study, and in others.7 Nevertheless, comparison of ISAAC Phases I and III showed that the prevalence of eczema increased in most countries, independently of their socioeconomic status.2,3,21

Since our focus was asthma, we further analysed clinical features in the 485 children who reported symptoms in the previous 12 months. Almost 11% reported more than 12 episodes of wheezing in that period and about a quarter had frequent sleep disturbance episodes. Furthermore, a high percentage (27%) had episodes of wheezing that interfered with speech, as seen in other countries,5–7 about one third had exercise-induced wheezing and a high proportion (71%) reported episodes of nocturnal cough. In addition, almost 50% had a moderate degree of bronchial obstruction. Although these findings may have been biased by manifestations misinterpreted as wheezing, by reporting of cough due to causes other than asthma or by suboptimal technical performance of peak flow by some children, it should be stressed that, in a high proportion of cases symptoms clustered together in the same children. Thus, our results show that a high percentage of children in Luanda are asthmatic and frequently have uncontrolled symptoms. This is in line with ISAAC study findings of the highest prevalence of symptoms of severe asthma among children with current wheeze being observed in low and middle-income countries.1,11 Globally, asthma should be regarded as a priority in terms of non-communicable diseases, as stated in the 2018 GAN - Global Asthma Network Report.2

We also identified risk factors for asthma. In the total sample of children, rhinitis increased almost nine-fold the risk of having asthma, as seen in other countries10,22–24 and in Angolan adolescents.12 Rhinitis is a known risk factor for asthma and may worsen asthma symptoms.10,25 In our study, in children with asthma, rhinitis was associated with significantly more wheezing episodes and nocturnal cough. We also identified eczema as another risk factor, since current eczema increased the risk of having asthma four-fold, as also seen in adolescents,12 and in reports showing a relationship between early onset of atopic eczema and subsequent respiratory disease in schoolchildren.26,27

Using AC-split air conditioning system was also a significant risk factor, as seen in other studies.12,28 This system may constitute a risk because cleaning it is difficult, which may allow accumulation of allergens,29 microorganisms and irritating substances.

We also detected drugs as risk factors for asthma. Antibiotics given to children during their first year of life increased the risk of asthma, as seen in ISAAC studies.30 A high frequency of paracetamol intake was another risk factor, which is also in agreement with ISAAC findings,30,31 was also reported in Angolan adolescents,10 and is also a risk factor for rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema.30,31 Maternal smoking during the child's first year of life also increased the risk of asthma, as reported in the ISAAC study, which also showed an increased risk of rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema.32 Furthermore, multinational, longitudinal studies performed in Europe showed that maternal smoking during pregnancy and the child's first year of life is a significant risk factor for subsequent development of wheezing in early childhood or adolescence.33,34 A small study performed in Mozambique, in asthmatic and non-asthmatic children, aged between 18 months and eight years, also showed that having at least one parent who smoked was a significant risk factor for asthma.23 Further studies are needed in African and other developing countries.

In contrast, using electricity as cooking system was a protective factor against asthma, which may be explained by the fact that children in homes that use this form of energy are less exposed to toxic fumes than those from homes where coal (open fire) is used for cooking. In fact, coal-based cooking has been shown to be a risk factor for asthma, in many studies.2,35

Our study had several limitations. It is based on self-reports by parents/guardians of the children and may, therefore, be influenced by various types of bias, although the ISAAC questionnaire makes it likely that reported symptoms significantly reflect the clinical situation.36 Some parents/guardians did not know some of the terms used in the questionnaire, as seen in other ISAAC studies. In addition, all children were from urban areas and relatively well-off families and results may not be fully extrapolated to children from poorer, rural areas. Some other potentially relevant risk factors, such as family history of asthma, were not included in our analysis, which partially impaired full comparisons with other studies. The ISAAC questionnaire on environmental exposure is validated but its level of detail may not be sufficient for some of the risk factors. Lastly, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow analysis of interrelationships between different diseases, in patterns of multimorbidity or risk factors.

ConclusionAsthma and related allergic diseases are a public health problem in children from Luanda, and a high proportion of children with asthma are frequently symptomatic and this may also apply to other developing countries. Thus, preventive and control measures should be implemented to deal with this problem.

Author contributionsMA participated in the study design, data collection and analysis, as well as in writing the manuscript; OL and FQ participated in data collection and analysis; JRP participated in the study design and writing the manuscript; JMRG carried out the statistical analyses and participated in writing the manuscript; LTB supervised the whole project and participated in study design, data analysis and writing the manuscript.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestOL, FQ, and JMRG have no conflicts of interest and have not been funded.

MA has received support to attend international congresses from MSD and from AstraZeneca Angola.

LTB has received support to attend EAACI congresses from Victoria Laboratories and Menarini and has been paid lecture fees by Novartis, AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Menarini.

JRP has received support to attend EAACI congress from Roxall.

We would like to thank all Directory Boards of all schools involved in the study, as well as all the participating children and their parents/guardians.

Questionnaire copies were supplied by AstraZeneca and MSD Angola. Peak flow metres were supplied by GlaxoSmithKline Angola. No drug company had any input in the design or implementation of the study.