Viral hepatitis is an endemic and epidemic disease of relevance in public health. This study estimated the frequency of viral hepatitis by occupational and non-occupational infections and analyzed the factors associated with case notifications in Brazil from 2007 to 2014.

Material and methodsThis was an exploratory epidemiological study using the Notifiable Diseases Information System database. Descriptive and multivariate analyses were performed.

ResultsThe frequency of viral hepatitis by occupational infections was 0.7%, of which 1.3% were due to hepatitis A virus (HAV), 45.1% hepatitis B virus (HBV), and 45.3% hepatitis C virus (HCV). There was a significant association of the disease with female sex [AOR=1.31; P=0.048], schooling [AOR=1.71; P<0.001], occupation [AOR=2.74; P<0.001], previous contact with an HBV or HCV-infected patient [AOR=5.77; P<0.001], exposure to accidents with biological materials [AOR=99.82; P<0.001], and hepatitis B vaccination [AOR=0.73; P=0.033].

ConclusionWhile there was a low frequency of viral hepatitis by occupational infections in Brazil from 2007 to 2014, these findings might be underreported and have been associated with individual and occupational characteristics. This reinforces the need for the adoption of prevention strategies in the workplace and for completeness of case notifications.

Viral hepatitis is an endemic disease affecting the population worldwide, with a heterogeneous distribution, especially the occurrence of hepatitis B. The global prevalence of hepatitis B in 2015 was 3.5%, with 257 million people living with hepatitis B virus (HBV). As for hepatitis C, there was a prevalence of 23.7 cases per 100 thousand inhabitants, with 71 million people affected by the virus. Alarmingly, hepatitis mortality worldwide increased by 22% between 2000 and 2015 [1]. In Taiwan, HBV is endemic with approximately 15–20% of the population testing positive for HBsAg and 2.5% for hepatitis C virus (HCV) [2]. In Turkey, hepatitis is moderately endemic [3]. In Brazil, hepatitis is also an endemic condition, with a heterogeneous distribution nationwide, especially hepatitis B [4].

Each year, three million health workers are subject to occupational exposure to hepatitis virus resulting in 70,000 HBV infections and 15,000 HCV infections [5]. Viral hepatitis by occupational infections are mostly investigated among health workers [2,6–8] and less investigated among those working as wastepickers [9], health students [10], and the military/police [3,11]. In addition, individuals working in nursing homes, garbage collection, manicure (foot care and finger nails), hairdressing, general services, and civil construction, among others, should also be considered to be at a higher exposure risk, as they can acquire various types of hepatitis virus and develop complications such as cirrhosis, esophageal varices [12], hepatic steatosis [13], among others.

In Brazil, both viral hepatitis infections and work accidents are mandatory reportable issues, given the magnitude of these events to the population's health, including their potential damage to one's physical and mental integrity. Case notification is extremely important from an epidemiological perspective to help develop prevention and control strategies. All cases are registered in the Notifiable Diseases Information System (SINAN in Brazil) through the completion of an investigation form [4,14].

Considering that notification indicators and the factors associated with viral hepatitis by occupational infection remain unknown in Brazil, this study aimed to estimate the frequency of viral hepatitis by occupational and non-occupational infections and to analyze the factors associated with case notifications in Brazil from 2007 to 2014. The findings reported herein may provide the basis for clinical and epidemiological surveillance, as well as for immunization and occupational health strategies.

2Material and methodsThis was an exploratory epidemiological study using individual data from mandatory notifications of viral hepatitis cases in Brazil from 2007 to 2014. Brazil is composed of 26 states and one Federal District, subdivided into five regions (North, Northeast, Midwest, Southeast, and South), with an estimated population of 208,494,900 residents in 2018 [15].

The notification data were collected using a case investigation form from SINAN information system, which consists of 52 variables grouped in blocks (general and individual information, epidemiological history, laboratory exams, and case summary) as well as information about the investigator in charge of the case notification [16].

In our study, we used the SINAN database on viral hepatitis cases from the Health Surveillance Secretariat of the Ministry of Health. This information system is used to register all mandatory reportable diseases in the country whose management is under responsibility of the federal government (Ministry of Health). Municipalities and states are only responsible for typing as well as data updating and routing to the headquarters. Regarding data quality, the municipalities that enter the data should timely check for duplication, case follow-up and closure.

All cases in which the source of infection had not been filled out in the notification form, were excluded from analysis. The dependent variable was the source of hepatitis infection (occupational or non-occupational). Occupational infection refers to the contamination by an infectious agent through work accidents during the act of working, while non-occupational infections have other sources of contamination such as sexual, injecting drug use, transfusional, among others. The independent (exploratory) variables in this study were sociodemographic characteristics, exposure and preventive factors, and clinical diagnostic aspects.

Data analysis was performed using the SPSS statistics for Windows version 17.0, Chicago, 2008. The data were described using absolute and relative frequencies, and the chi-square test was used to compare the proportions. Crude Odds Ratio (COR) was estimated to verify an association between the independent variables and the source of infection (occupational or non-occupational). The data were stratified by the most frequent types of hepatitis and similarities (A and B/C) to determine possible associations of the disease with protection and exposure factors. A P-value <0.05 (two-tailed) with a 95% confidence interval was considered statistically significant. A multivariate analysis was performed using logistic regression by the backward block method. The variables were inputted in the model at P<0.25 (X²) and by biological plausibility, and outputted by the likelihood ratio. Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) was estimated in the models. Two regression models were obtained, one for hepatitis A and one for hepatitis B and C, the separation was due to the transmission of the virus in the working environment. The diagnostics of the final models were obtained by the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test.

This study was approved by the institutional research ethics committee under protocol 1.249.977/2015. All researchers signed an informed consent form to have access to the database and to take full responsibility for data confidentiality.

3ResultsA total of 472,842 confirmed cases of viral hepatitis were reported to SINAN in Brazil from 2007 to 2014. Among them, only 45.8% (216,776) of the cases included information on the source of infection, which were considered in this study. The frequency of viral hepatitis by occupational infections, considering the total number of cases, was 0.7% (1493). Of these, 45.3%, 45.1% and 1.3% of the cases corresponded to HCV, HBV, and HAV infections, respectively; 2.4% were coinfections, 1.3% ignored; and 4.6% were lost/null/not applicable.

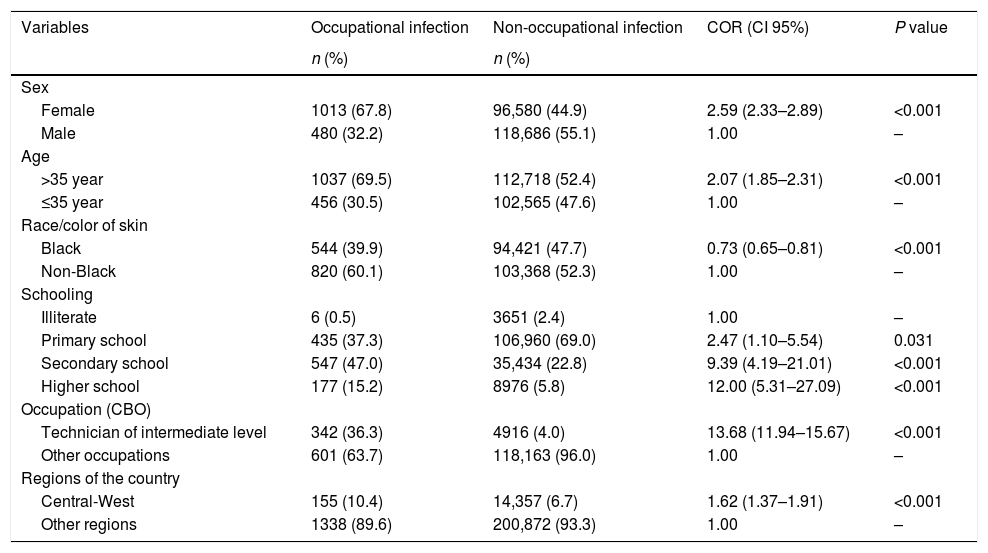

As shown in Table 1, there was a significant association between occupational hepatitis and sociodemographic variables (P<0.001), with a larger difference observed between technicians with secondary schooling and other professionals (COR=13.68). The data also revealed that individuals with higher educational levels are at a greater the risk of acquiring hepatitis from occupational infections (P<0.001).

Sociodemographic characteristics and the occurrence of viral hepatitis by occupational and non-occupational infections. Brazil, 2007 to 2014.

| Variables | Occupational infection | Non-occupational infection | COR (CI 95%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1013 (67.8) | 96,580 (44.9) | 2.59 (2.33–2.89) | <0.001 |

| Male | 480 (32.2) | 118,686 (55.1) | 1.00 | – |

| Age | ||||

| >35 year | 1037 (69.5) | 112,718 (52.4) | 2.07 (1.85–2.31) | <0.001 |

| ≤35 year | 456 (30.5) | 102,565 (47.6) | 1.00 | – |

| Race/color of skin | ||||

| Black | 544 (39.9) | 94,421 (47.7) | 0.73 (0.65–0.81) | <0.001 |

| Non-Black | 820 (60.1) | 103,368 (52.3) | 1.00 | – |

| Schooling | ||||

| Illiterate | 6 (0.5) | 3651 (2.4) | 1.00 | – |

| Primary school | 435 (37.3) | 106,960 (69.0) | 2.47 (1.10–5.54) | 0.031 |

| Secondary school | 547 (47.0) | 35,434 (22.8) | 9.39 (4.19–21.01) | <0.001 |

| Higher school | 177 (15.2) | 8976 (5.8) | 12.00 (5.31–27.09) | <0.001 |

| Occupation (CBO) | ||||

| Technician of intermediate level | 342 (36.3) | 4916 (4.0) | 13.68 (11.94–15.67) | <0.001 |

| Other occupations | 601 (63.7) | 118,163 (96.0) | 1.00 | – |

| Regions of the country | ||||

| Central-West | 155 (10.4) | 14,357 (6.7) | 1.62 (1.37–1.91) | <0.001 |

| Other regions | 1338 (89.6) | 200,872 (93.3) | 1.00 | – |

COR: Crude Odds Ratio; CBO: Brazilian Classification of Occupations.

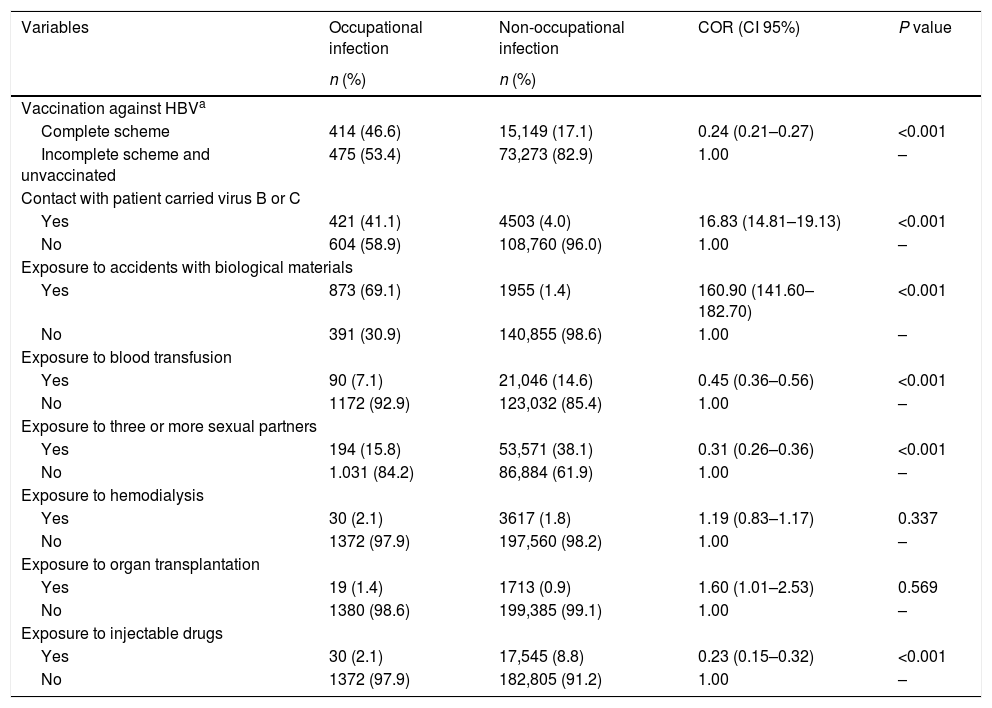

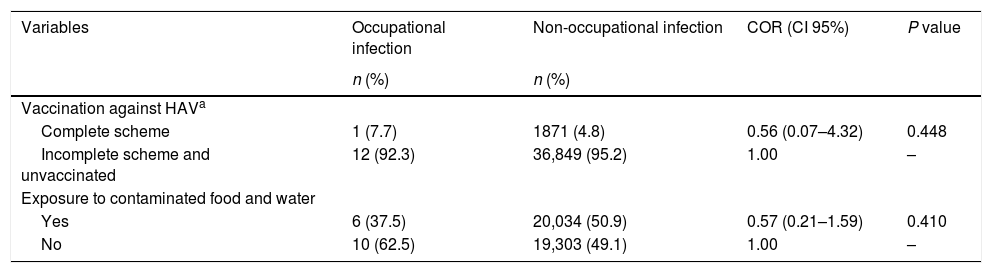

Exposure and protective factors were associated with cases of occupational hepatitis B and C (P<0.001), with larger differences observed for exposure to accidents with biological materials (COR=160.90) and contact with an HBV or HCV-infected patient (COR=16.83). Complete vaccination was negatively associated with the disease, therefore being considered as a protective factor (COR=0.24) (Table 2). No association these variables with hepatitis A cases were observed, as shown in Table 3.

Factors of protection and exposure and the occurrence of hepatitis B and C by occupational and non-occupational infections. Brazil, 2007 to 2014.

| Variables | Occupational infection | Non-occupational infection | COR (CI 95%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Vaccination against HBVa | ||||

| Complete scheme | 414 (46.6) | 15,149 (17.1) | 0.24 (0.21–0.27) | <0.001 |

| Incomplete scheme and unvaccinated | 475 (53.4) | 73,273 (82.9) | 1.00 | – |

| Contact with patient carried virus B or C | ||||

| Yes | 421 (41.1) | 4503 (4.0) | 16.83 (14.81–19.13) | <0.001 |

| No | 604 (58.9) | 108,760 (96.0) | 1.00 | – |

| Exposure to accidents with biological materials | ||||

| Yes | 873 (69.1) | 1955 (1.4) | 160.90 (141.60–182.70) | <0.001 |

| No | 391 (30.9) | 140,855 (98.6) | 1.00 | – |

| Exposure to blood transfusion | ||||

| Yes | 90 (7.1) | 21,046 (14.6) | 0.45 (0.36–0.56) | <0.001 |

| No | 1172 (92.9) | 123,032 (85.4) | 1.00 | – |

| Exposure to three or more sexual partners | ||||

| Yes | 194 (15.8) | 53,571 (38.1) | 0.31 (0.26–0.36) | <0.001 |

| No | 1.031 (84.2) | 86,884 (61.9) | 1.00 | – |

| Exposure to hemodialysis | ||||

| Yes | 30 (2.1) | 3617 (1.8) | 1.19 (0.83–1.17) | 0.337 |

| No | 1372 (97.9) | 197,560 (98.2) | 1.00 | – |

| Exposure to organ transplantation | ||||

| Yes | 19 (1.4) | 1713 (0.9) | 1.60 (1.01–2.53) | 0.569 |

| No | 1380 (98.6) | 199,385 (99.1) | 1.00 | – |

| Exposure to injectable drugs | ||||

| Yes | 30 (2.1) | 17,545 (8.8) | 0.23 (0.15–0.32) | <0.001 |

| No | 1372 (97.9) | 182,805 (91.2) | 1.00 | – |

COR: Crude Odds Ratio; HAV: hepatitis A virus.

Factors of protection and exposure and the occurrence of hepatitis A by occupational and non-occupational infections. Brazil, 2007 to 2014.

| Variables | Occupational infection | Non-occupational infection | COR (CI 95%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Vaccination against HAVa | ||||

| Complete scheme | 1 (7.7) | 1871 (4.8) | 0.56 (0.07–4.32) | 0.448 |

| Incomplete scheme and unvaccinated | 12 (92.3) | 36,849 (95.2) | 1.00 | – |

| Exposure to contaminated food and water | ||||

| Yes | 6 (37.5) | 20,034 (50.9) | 0.57 (0.21–1.59) | 0.410 |

| No | 10 (62.5) | 19,303 (49.1) | 1.00 | – |

COR: Crude Odds Ratio; HAV: hepatitis A virus.

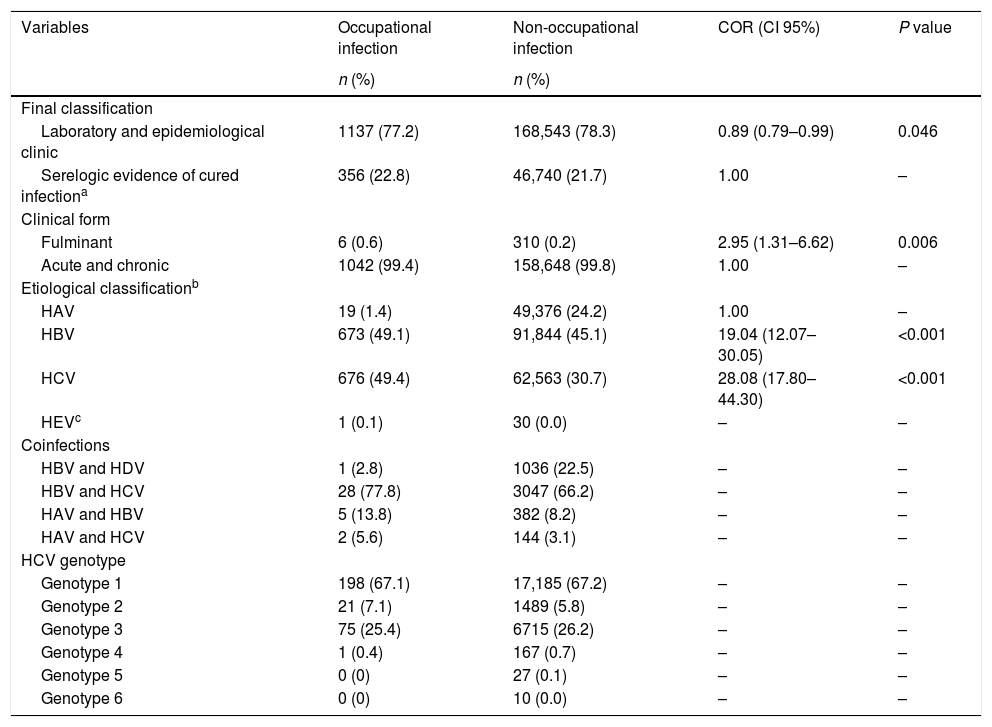

The clinical and diagnostic aspects are described in Table 4. There was an association with the fulminant clinical form of the disease (P<0.001). In addition, the etiological classification for HBV and HCV was associated with cases of viral hepatitis due to occupational infections. The most frequent coinfection occurrence was between HBV and HCV in 77.8% of the cases of occupational infection, with a higher frequency of HCV genotypes 1 and 3.

Clinical aspects and the occurrence of viral hepatitis by occupational and non-occupational infections. Brazil, 2007 to 2014.

| Variables | Occupational infection | Non-occupational infection | COR (CI 95%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Final classification | ||||

| Laboratory and epidemiological clinic | 1137 (77.2) | 168,543 (78.3) | 0.89 (0.79–0.99) | 0.046 |

| Serelogic evidence of cured infectiona | 356 (22.8) | 46,740 (21.7) | 1.00 | – |

| Clinical form | ||||

| Fulminant | 6 (0.6) | 310 (0.2) | 2.95 (1.31–6.62) | 0.006 |

| Acute and chronic | 1042 (99.4) | 158,648 (99.8) | 1.00 | – |

| Etiological classificationb | ||||

| HAV | 19 (1.4) | 49,376 (24.2) | 1.00 | – |

| HBV | 673 (49.1) | 91,844 (45.1) | 19.04 (12.07–30.05) | <0.001 |

| HCV | 676 (49.4) | 62,563 (30.7) | 28.08 (17.80–44.30) | <0.001 |

| HEVc | 1 (0.1) | 30 (0.0) | – | – |

| Coinfections | ||||

| HBV and HDV | 1 (2.8) | 1036 (22.5) | – | – |

| HBV and HCV | 28 (77.8) | 3047 (66.2) | – | – |

| HAV and HBV | 5 (13.8) | 382 (8.2) | – | – |

| HAV and HCV | 2 (5.6) | 144 (3.1) | – | – |

| HCV genotype | ||||

| Genotype 1 | 198 (67.1) | 17,185 (67.2) | – | – |

| Genotype 2 | 21 (7.1) | 1489 (5.8) | – | – |

| Genotype 3 | 75 (25.4) | 6715 (26.2) | – | – |

| Genotype 4 | 1 (0.4) | 167 (0.7) | – | – |

| Genotype 5 | 0 (0) | 27 (0.1) | – | – |

| Genotype 6 | 0 (0) | 10 (0.0) | – | – |

COR: Crude Odds Ratio.

Serologic evidence of cured infection refers to serological markers of past infection as Anti-HBs and Anti-HBc IgG.31 This information is made present, since the notification must be closed and the final classification field filled in within 180 days after registration suspected or confirmed case.

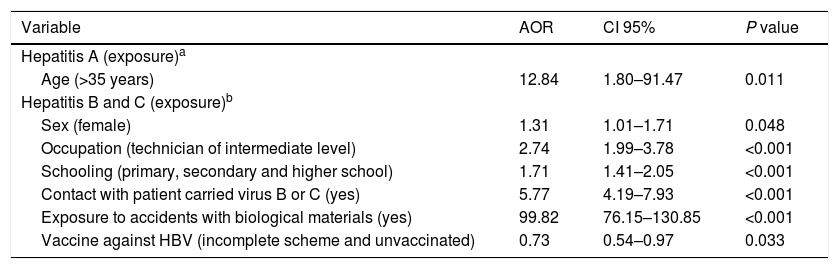

The multivariate analysis indicated that among the hepatitis A cases only the age [AOR=12.84 (95% CI: 1.80–91.47, P=0.011)] remained associated with occupational infections adjusted for exposure to contaminated food and water and to HAV vaccination. Among the cases of hepatitis B and C, the female sex [AOR=1.31; P=0.048], occupation [AOR=2.74; P<0.001], schooling [AOR=1.71; P<0.001], contact with HBV or HCV-infected patients [AOR=5.77 P<0.001)], exposure to accidents with biological materials [AOR=99.82; P<0.001] and HBV vaccination [AOR=0.73; P=0.033) were associated with occupational infections adjusted for age and race/skin color. The final model presented a good fit, P=0.700 (Table 5).

Results of the multivariate analysis for the occurrence of hepatitis A and hepatitis B and C by occupational and non-occupational infections. Brazil, 2007 to 2014.

| Variable | AOR | CI 95% | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis A (exposure)a | |||

| Age (>35 years) | 12.84 | 1.80–91.47 | 0.011 |

| Hepatitis B and C (exposure)b | |||

| Sex (female) | 1.31 | 1.01–1.71 | 0.048 |

| Occupation (technician of intermediate level) | 2.74 | 1.99–3.78 | <0.001 |

| Schooling (primary, secondary and higher school) | 1.71 | 1.41–2.05 | <0.001 |

| Contact with patient carried virus B or C (yes) | 5.77 | 4.19–7.93 | <0.001 |

| Exposure to accidents with biological materials (yes) | 99.82 | 76.15–130.85 | <0.001 |

| Vaccine against HBV (incomplete scheme and unvaccinated) | 0.73 | 0.54–0.97 | 0.033 |

AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio.

While the frequency of viral hepatitis by occupational infections was low (<1% in this study), these findings may be underestimated due to the lack of notifications of several cases diagnosed across the country. In addition, in less than half of the cases the field “source of infection” was not filled out; it is an essential but not mandatory requirement. The results presented herein are relevant as the occurrence of viral hepatitis can be prevented in occupational environments, where there is a higher frequency of HCV and HBV infections.

Previous studies in the literature have also reported similar estimates of viral hepatitis among garbage collectors (1.6% for HCV) [9]; individuals who had occupational accidents in Bahia state (0.2% for HBV and 0.1% for HCV) [17]; seafarers who presented risks of acquiring HAV and HBV in Denmark [18]; and among hospital workers – where 33.0% of the viral infections were due to HCV, HBV, and hepatitis G virus (HGV) [19].

The health workers’ risk of acquiring HBV and HCV is estimated to be 1168 and 1263 per year, respectively, in Taiwan [2] estimation based on a total of inpatient-days per year, as well as 8617 and 24,000 per year, respectively, in Egypt [20] estimation using Kane's model. As for Brazil, distinct realities can be observed. Although the estimates and most of the studies are related to HBV and HCV infection in health workers, other non-health-related workers are likewise at risk of acquiring these and other types of hepatitis viruses.

The female sex presented a higher risk for viral hepatitis B and C by occupational infections [6,7,17,21–23]. This may be explained by the fact that the majority of affected individuals were female health professionals with a mid-level technician occupation. Individuals with higher educational levels are at a greater the risk of acquiring hepatitis from occupational infections, since schooling determines the complexity of labor activities with greater exposure.

The age was a determinant factor for hepatitis A, with a greater risk among individuals older than 35 years, adjusted by ingestion of contaminated food and water and non-vaccination, which shows the predisposition among non-vaccinated. Furthermore, as age advances the individual experiences a longer work time, resulting in high confidence and negligent attitudes that may put their health at risk.

The contact with an HBV or HCV-infected patient increased the risk of developing hepatitis B and C by occupational infections. In Turkey, this was considered a risk factor for hepatitis B in the military [3]; in a hospital in Brazil, 0.66% of the patients were seroconverted to HCV [24]. In Bahia, a state of Northeast from Brazil, of 1.0% of the cases with a positive source for HBV and 0.6% for HCV, 0.2% were tested positive for HBV and 0.1% for HCV [17]. In addition, one case with a positive source for HCV presented seroconversion in nine days [25]. The establishment of the serology of the individual source is relevant for prophylaxis and for the evaluation of the clinical condition of the infected person [21].

Exposure to accidents with biological materials may potentially lead to greater risk of acquiring hepatitis B and C. This risk factor is related to needle mishandling, movement of the patient when medications are administered, regular waste bags containing sharp objects, and dirty clothes, which may result in contact with blood and contaminated fluids [2,7–9,11,19,20,23–26]. The risk of infections due to needle injuries is the most commonly reported mode of transmission in the literature, which ranges between 40.0% for HBV and 3–10% for HCV [27].

The findings reported in our study indicate the risk factors associated with occupations that expose workers to biological risks, especially in health-related jobs. However, non-health-related occupations were also reported. Therefore, preventing occupational accidents in work environments is of utmost relevance, in a way that workers should be instructed to use individual and collective protective equipment, and programs that support the development of safe work activities should be implemented. The impacts caused by viral hepatitis affect the workers’ biopsychosocial wellness, not to mention that the costs of prevention of hepatitis are substantially lower than those of treatment.

While HBV and HAV vaccines are the best preventive strategy, evidenced as a protective factor for viral hepatitis, the overall workers’ vaccination status remains poor [28], even with the HBV vaccine made available in public health services in Brazil. After completing the vaccination scheme for HBV, checking for immunity through anti-HBs serology is highly recommended [29] for health care workers or other high risk populations, as the three doses of the vaccine may not guarantee protection. The complete adult vaccination card and other specific vaccines according to the inherent risks of each occupation should be the mandatory passport for admission to work, given that taking such a vaccine is not a mandatory requirement for any professional category currently in Brazil.

A study carried out with students and health workers attending a federal university revealed that 95.7% of the participants who were proven to have complete vaccination were anti-HBs positive and 4.3% of them were anti-HBs negative. In the group with unproven vaccination, 18.9% of the participants were found to be susceptible to HBV. Health workers were more susceptible to HBV than were students, with a prevalence of 12.5% of susceptibility. Such a prevalence was higher among those with unproven vaccination (31.6%) [30]. These results reinforce the need for vaccination and immunity screening.

For those workers who presented HCV, the HCV-RNA was realized to verify the virus genotype which assists in the treatment. The genotypes are classified into six types further containing subdivisions, those with greater spread in the world are 1, 2 and 3 [31]. In the present study, the highest proportion was 1 and 3 in agreement with the distribution in Brazil, in populations of different regions type 1 presented 64.9% and type 3, 30.2% [32].

This study has some limitations, which include: (i) the analysis of big data, which may result in spurious associations, although the literature and biological plausibility were used to include the variables; (ii) the scarcity of similar population-based studies (with general work categories) with the same outcome to compare the findings – thus alike studies addressing hepatitis and work accidents were discussed here; (iii) viral hepatitis cases by occupational infections are underreported due to the difficulty of establishing the epidemiological technical nexus, failure to report by health professionals, and/or those responsible for public and private institutions and the completeness of the variables contained in the notification form, especially regarding the source of infection; (iv) cases of viral hepatitis due to non-occupational infection with age groups different from those who had occupational infection. The source of infection was not completed in 54.2% of the notifications, which indicated a poor completeness of this information. This is the first study evaluating the notifications of viral hepatitis by occupational infections in Brazil. It is expected to determine relevant aspects that may subsidize the clinical practice and health surveillance by means of health promotion and disease prevention strategies as well as to facilitate the early diagnosis of communicable diseases during work activities.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated a low frequency of viral hepatitis by occupational infections in Brazil from 2007 to 2014; however, of note, these data may be underreported. The risk factors for HBV and HCV from occupational infections were female sex, schooling, occupation, contact with an HBV or HCV-infected patient, and exposure to accidents with biological materials. As expected, vaccination was found to be a protection factor. The age (>35 years old) was considered a risk factor for HAV infection. Further studies should analyze these parameters according to professional occupation and regions or states in Brazil. Ultimately, these results can be used to implement a mandatory vaccination policy for Brazilian workers.AbbreviationsHAV hepatitis A virus hepatitis B virus hepatitis C virus hepatitis D virus hepatitis G virus Notifiable Diseases Information System HBV surface antigen antibodies against HBsAg antibodies against HCV

Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – CAPES) – funding code 001.

National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq) – financial support.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors thank the Health Surveillance Secretariat of the Ministry of Health in Brazil for providing access to the databases used in this study.