Suicide is one of the leading causes of avoidable death. Gathering national data on suicidal behaviour incidence is crucial to develop evidence-based public policies. The study has two primary objectives: (1) to determine the incidence of suicide attempts in Spain and related risk factors, and (2) to analyze the efficacy of secondary prevention programmes to prevent suicide re-attempting in comparison to treatment as usual (TAU).

Materials and methodsMultisite, coordinated, cohort study with three nested randomized controlled trials. A cohort of 2000 individuals (age >=12) with suicidal behaviour will be recruited at ten sites distributed across Spain. Assessments will be conducted within 10 days of the suicide attempt (V0-baseline visit) and after 12 months (V4-last visit) and will include clinician reported and participant reported outcomes (PROs). Between V0 and V4, PROs will be collected remotely every three months (V1, V2 and V3). Optatively, cohort participants will participate in three nested randomized-controlled-trials (RCTs) evaluating different secondary prevention interventions: Participants aged 18 years and older will be randomly allocated to: Telephone-based Management+TAU vs. TAU or iFightDepression-Survive+TAU vs. TAU. Participants aged between 12 and 18 years will be allocated to a specific intervention for youths: Self Awareness of Mental Health+TAU vs. TAU.

ResultsThis study will provide interesting data to estimate suicide attempt incidence in Spain. and will provide evidence on three.

ConclusionsEvidence on three potentially efficacious interventions for individuals at high risk of suicide will be obtained, and this could improve the treatment given to these individuals.

Trial registrationNCT04343703

Suicide is one of the leading causes of avoidable death worldwide.1 In Spain, rates of suicide attempts are estimated in 99.1 for every 100000 inhabitants.2 The Spanish Statistical Office reported that suicide is the principal cause of avoidable mortality in our country, with 3679 individual's death by suicide in 2017 (2718 males and 961 females). Suicide is also one of the main causes of death among young people (both genders).1 The number of adolescent's deaths that result from suicide has been increasing dramatically, with evidence suggesting that suicide accounts for 7.3% of all deaths in the 15–19 years age group globally.3 The negative impact of suicide for societies is unquestionable, and therefore, its prevention is an emerging priority for public health systems.4

A review of the literature suggests that an increased risk for suicide in both adults and young people, might be attributable to neurobiological factors,5–7 stressful events8 (e.g., psychological trauma),9–11 aberrant cognitive processes,12 personality traits,13,14 and mental health disorders.15,16 Among the latter, a recent meta-analysis found an estimated mean prevalence of any mental disorder of 80.8% among individuals who made a suicide attempt.16 Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the diagnosis most commonly associated with suicide. In parallel, evidence strongly suggests that an increased risk of re-attempting suicide is directly related with a previous history of suicidal behaviour.17 In a recent cohort study conducted in the United States, it was shown that 19.7% of those who had engaged in suicidal behaviour showed another suicide attempt within the year after the first one.17 A large proportion of individuals who commit suicide had been in contact with a healthcare provider in previous days.18 Therefore, the lack of care continuity has been pointed out as a risk factor for suicide attempt repetition, and therefore suicide leading to death.19

Altogether, as summarized by Zalsman et al.,20 this evidence has been crucial to develop and implement secondary prevention strategies that include a wide range of follow-up actions, such as sending letters to suicide attempters, regular telephone follow-up or via SMS, follow-up visits prioritizing specialized healthcare, and 24/7 hotlines. In Spain, several actions have been taken across different regions to develop and improve primary and secondary suicide prevention strategies, but no global nation plan for this purpose has been so far implemented.21,22 Previous research suggested that a telephone-based programme for patients discharged from the emergency room following attempted suicide had a positive effect to prevent reattempts after one-year follow up.23–25 E-health interventions have emerged as promising tools to reach individuals at risk, who might otherwise be missed in traditional face-to-face treatments. Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for depression might be effective for decreasing suicidal ideation and MDD symptoms.26 Given the relevance of care continuity after a suicide attempt, e-health programmes might constitute an effective tool to provide care to a wider group of individuals. Lastly, but not least, data shows that youth represent a high risk-population, not only for the large incidence of suicidal behaviour in this age-group, but because a large proportion of psychiatric symptoms have their onset during childhood and adolescence.27 Some therapeutic approaches, tested in relatively small samples, have shown promising results for preventing suicide behaviour among adolescents, mainly programmes based on CBT28 or Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT).29 The SEYLE project is an example of a large and successful RCT, but that intervention was focused on primary rather than secondary prevention,30 Therefore, implementing and evaluating tailored interventions for youth at high risk of suicide is still needed.

The SURVIVE study is a multisite cohort study, with three nested randomized, controlled trials and a primary endpoint of suicide repetition after 12 months of the initial assessment. The study has two primary objectives:

- 1.

To estimate the incidence of suicide attempts in Spain and its relevant risk factors.

- 2.

To investigate the efficacy of three secondary prevention programmes (i.e., telephone-based management [TBM], iFightDepression-Survive [iFD-Survive] and Self-awareness of Mental Health [SAM] to prevent suicide attempt repetition.

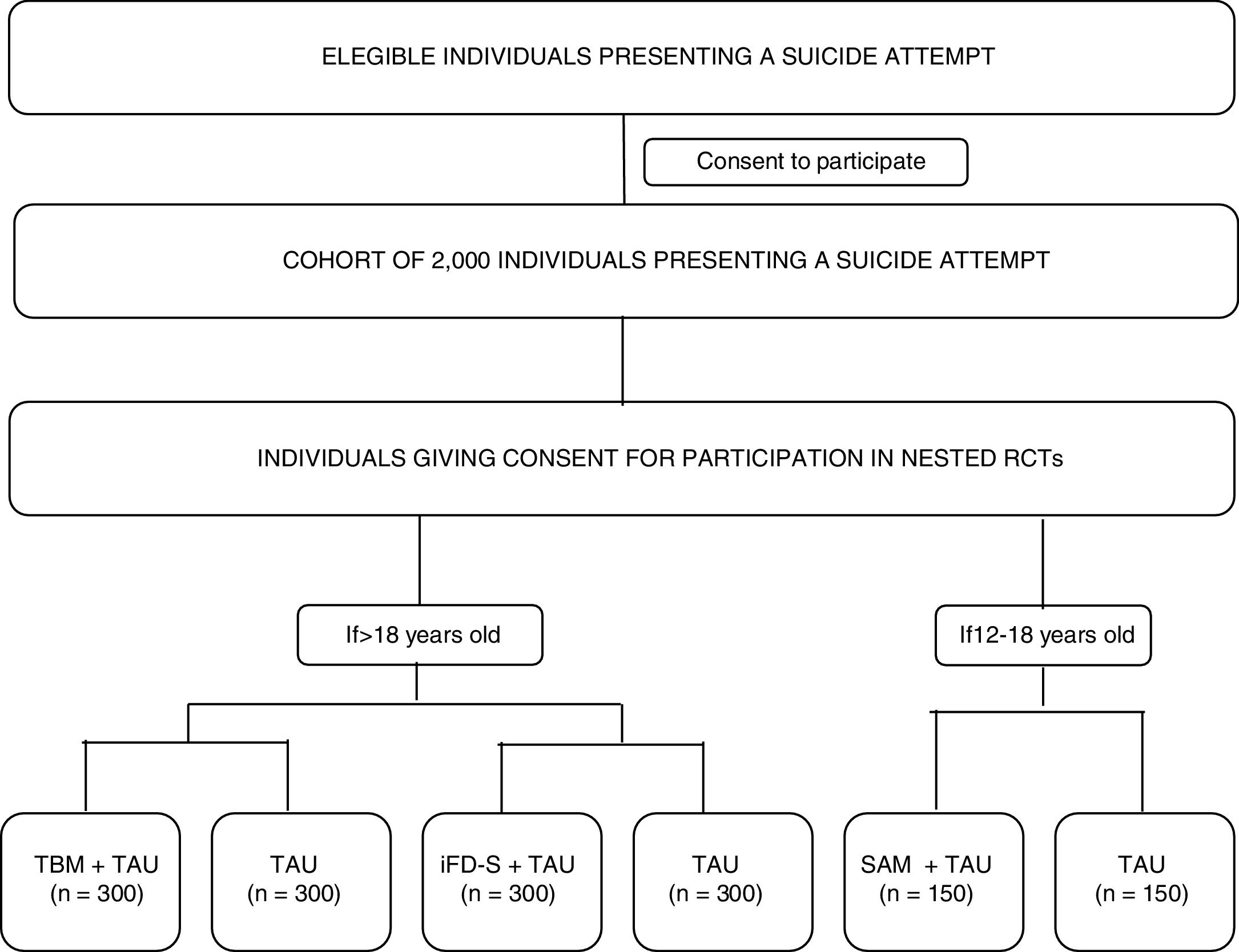

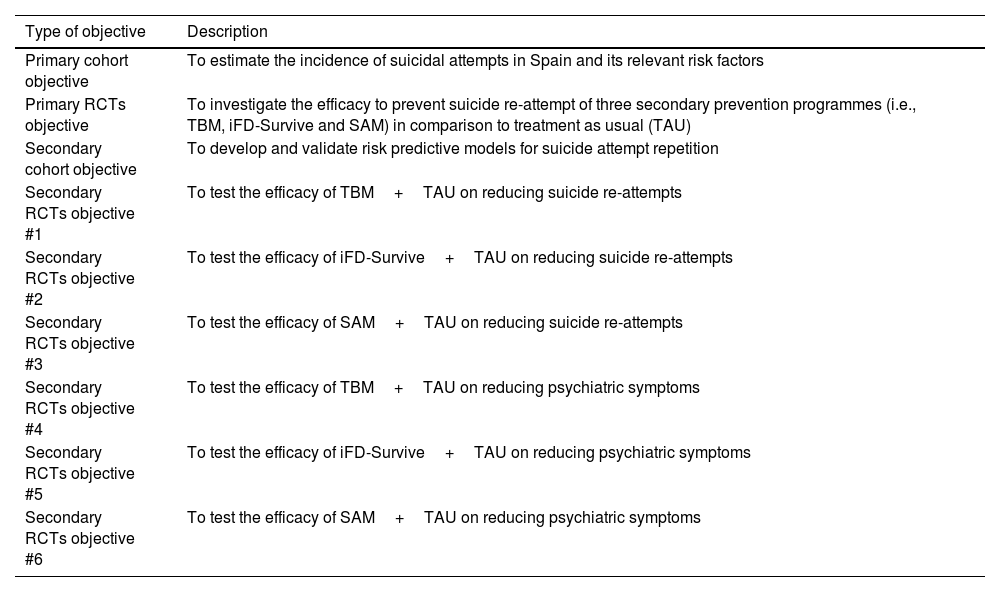

The study's primary and specific objectives are listed in Table 1. Fig. 1 shows a study outline.

Objectives of the SURVIVE study.

| Type of objective | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary cohort objective | To estimate the incidence of suicidal attempts in Spain and its relevant risk factors |

| Primary RCTs objective | To investigate the efficacy to prevent suicide re-attempt of three secondary prevention programmes (i.e., TBM, iFD-Survive and SAM) in comparison to treatment as usual (TAU) |

| Secondary cohort objective | To develop and validate risk predictive models for suicide attempt repetition |

| Secondary RCTs objective #1 | To test the efficacy of TBM+TAU on reducing suicide re-attempts |

| Secondary RCTs objective #2 | To test the efficacy of iFD-Survive+TAU on reducing suicide re-attempts |

| Secondary RCTs objective #3 | To test the efficacy of SAM+TAU on reducing suicide re-attempts |

| Secondary RCTs objective #4 | To test the efficacy of TBM+TAU on reducing psychiatric symptoms |

| Secondary RCTs objective #5 | To test the efficacy of iFD-Survive+TAU on reducing psychiatric symptoms |

| Secondary RCTs objective #6 | To test the efficacy of SAM+TAU on reducing psychiatric symptoms |

Note. RCT=Randomized Controlled Trial. TBM=Telephone-Based Management. iFD-Survive=iFightDepression-Survive. SAM=Self Awareness of Mental Health.

To estimate the incidence of suicidal behaviour in Spain participating sites will be distributed across five Spanish regions. Participants aged 18 years and older will be recruited at the psychiatric emergency ward of public, general, university hospitals in Catalonia (Hospital Clínic; Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí; Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau; Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol; Parc de Salut Mar); Madrid (Hospital Clínico San Carlos; Hospital Universitario La Paz); Basque Country (Hospital Universitario Araba-Santiago); Andalusia (Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocio); and Asturias (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias). Youth participants (aged between 12 and 18 years) will be recruited at all sites, except two hospitals in Catalonia that lack children mental health services (i.e., Parc de Salut Mar and Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau). The catchment area of the participating sites comprises between 350,000 and 600,000 inhabitants, which is considered large enough to reflect the incidence of suicidal behaviour in each area. The location of all sites is urban and patients of smaller rural areas are referred to them. Study-related coordination activities for adult participants will be performed by the team at Parc de Salut Mar, while study-related coordination activities for adolescent participants will be managed from Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias.

ParticipantsEligibility criteriaPatients (and legal guardians in case of minors) must provide written, informed consent before any study procedure.

General inclusion criteriaPatients eligible for the cohort study must comply with all of the following:

- 1.

Female and males, age >=12 years

- 2.

Having presented suicidal behaviour within the last 10 days

- 3.

Willing and able to comply with study procedures and to give written informed consent.

- 1.

Incapacity to give informed consent

- 2.

Lack of fluency in Spanish

- 3.

Currently taking part in another clinical study which, in the opinion of the investigator, is likely to interfere with the objectives of the SURVIVE study.

Patients must comply with additional inclusion criteria to participate in the RCTs: Participation in the telephone-based management programme (TBM) and iFightDepression – Survive (iFD-Survive) is restricted to participants over 18 years.

Specific inclusion criteria for participation in iFD-Survive consist of:

- 1.

Minimum digital literacy and availability of an internet device (tablet, computer, smartphone)

- 2.

Depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 scores above five)

Participants between 12 and 18 years of age will be invited to participate in the Self Awareness of Mental Health (SAM) intervention.

Recruitment and follow upEach site will screen potential participants until the sample size requirement being achieved (N=2000). Participants will be followed during 12 months upon confirmation of selection criteria. Participants will be provided with a brief overview of the study and consent to be contacted by phone to arrange a pre-screening visit will be verbally obtained. This pre-screening visit will be scheduled for those patients who will be willing to participate in the study. Individuals will not receive any type of compensation for their participation.

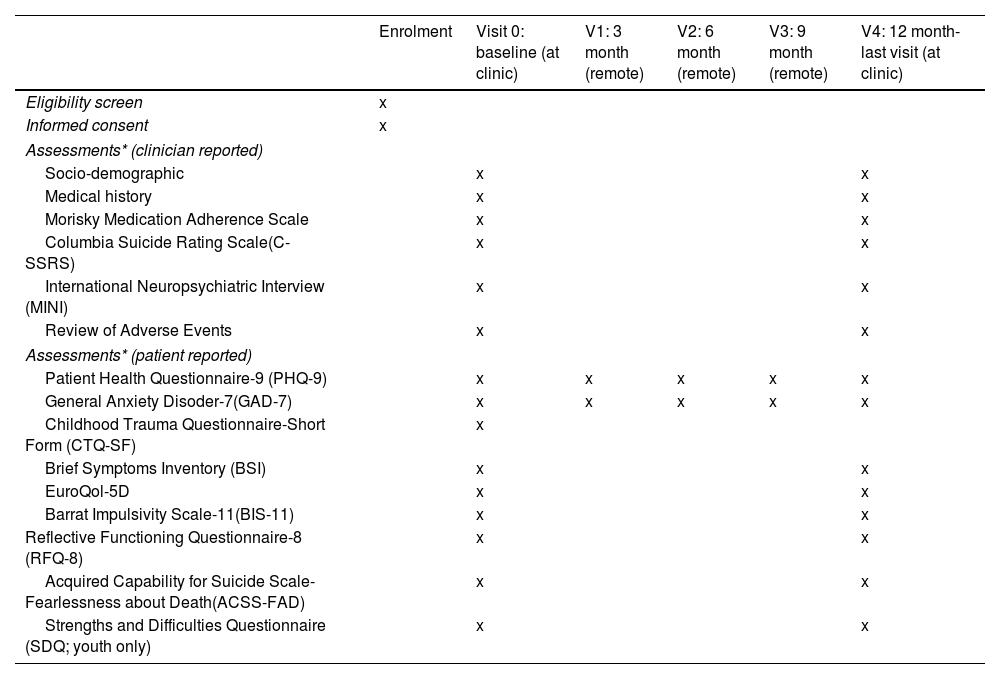

Study proceduresEligible participants will be asked for consent to participate in the cohort study. Participation in the nested RCTs will be presented as optional procedures (meaning that a given participant can decide to participate in the cohort study, but not in the RCTs). Those that give consent to participate in the optional procedures will be randomized to the RCT branches, depending on the inclusion/exclusion criteria listed above (see Participants section). The whole cohort will be assessed at the clinic using a full battery of clinical interviews, and participant-reported outcomes (PROs) at two time-points: baseline (V0-within 10 days of the suicide attempt) and month 12- (V4-last visit). A 10-day window will be available to conduct these assessments. In addition, intermediate assessments will be conducted remotely at month 3 (V1), month 6 (V2), and month 9 (V3) of the baseline visit. Participants will receive a study email every time that an assessment is available to be completed. PROs will be available online to be completed at the aforementioned time points, with a 7-day window. All the assessments will be performed through an electronic, patient-reported outcomes system (ePRO) which will randomize participants to RCT arms and allow the monitoring of participant compliance. Table 2 describes the time and events of the study.

SPIRIT diagram: Time and events table SURVIVE study.

| Enrolment | Visit 0: baseline (at clinic) | V1: 3 month (remote) | V2: 6 month (remote) | V3: 9 month (remote) | V4: 12 month-last visit (at clinic) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility screen | x | |||||

| Informed consent | x | |||||

| Assessments* (clinician reported) | ||||||

| Socio-demographic | x | x | ||||

| Medical history | x | x | ||||

| Morisky Medication Adherence Scale | x | x | ||||

| Columbia Suicide Rating Scale(C-SSRS) | x | x | ||||

| International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) | x | x | ||||

| Review of Adverse Events | x | x | ||||

| Assessments* (patient reported) | ||||||

| Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) | x | x | x | x | x | |

| General Anxiety Disoder-7(GAD-7) | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF) | x | |||||

| Brief Symptoms Inventory (BSI) | x | x | ||||

| EuroQol-5D | x | x | ||||

| Barrat Impulsivity Scale-11(BIS-11) | x | x | ||||

| Reflective Functioning Questionnaire-8 (RFQ-8) | x | x | ||||

| Acquired Capability for Suicide Scale-Fearlessness about Death(ACSS-FAD) | x | x | ||||

| Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; youth only) | x | x | ||||

Note. *Young versions of each assessment instrument will be used when appropriate.

The SURVIVE trial involves two interventions designed to participants over 18 years: TBM and iFD-Survive. Participants aged 12–18 years will receive a tailored intervention (SAM). Specifications for each one of them are as follows:

- (1)

Telephone-based management (TBM) involves three procedures. The first, is a 15–20min “making contact” call at one week of enrollment in the study. In this call, the case manager introduces him/herself, and assesses the current suicide risk. Thereafter, there is a “follow-up” phase that involves 5–10min follow up calls at 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. Information regarding the current treatment, adherence to mental health services and current life stressors is collected at each one of these calls. Lastly, and if suicide risk is detected, a “crisis intervention” procedure is initiated. The “crisis intervention” involves a 15–45min call tailored to the participant's characteristics and context. If deemed necessary, an emergency appointment at the clinic is scheduled. A detailed description of the intervention can be found elsewhere.23,24

- (2)

The iFightDepression-Survive (iFD-Survive) is an extension of the iFightDepression programme (iFD; www.ifightdepression.com), a cognitive-behavioural, internet-based self-management tool,31 developed by the European Alliance Against Depression (EAAD). In its original format, the iFD is intended to address mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms by focusing on different treatment-targets for depression: behavioural activation, cognitive restructuring, sleep regulation, mood monitoring, and healthy lifestyle habits. The content of each module is intended to be followed over 1 week and consists of written information, home-tasks and worksheets. For the present study, an additional module (iFD-Survive) was developed. A panel of mental health experts in suicide and cognitive-behavioural interventions, together with the collaboration of patient's associations, was consulted to guide the development of its content. The iFD-Survive includes a safety plan, and is based on enhancing skills to effectively self-manage behaviours and emotions during times of crisis. The telephone guidance (2h per participant) that is provided in the original iFD programme, will be tailored for participants in the iFD-Survive.

- (3)

The Self Awareness of Mental Health (SAM) is an adaptation of the Youth Awareness of Mental Health programme, originally developed for the Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe (SEYLE) study.30,32 The SAM has been specifically developed to: raise mental health awareness about risk and protective factors associated with suicide, provide knowledge about depression and anxiety, and enhance the skills needed to deal with adverse life events, stress, and suicidal behaviours. The intervention will consist of five, face-to-face sessions of 45–60min that will be held at each clinic.

- (4)

Treatment as Usual (TAU) will vary across sites, however it generally implies a combination of case management strategies (including telephone and specialized mental health follow up) and pharmacotherapy. For this study, any nonspecific intervention to address suicidal behaviour or to prevent suicide will be considered as treatment as usual, so TAU will consist of any routine procedures applied at each participating site. All participants will receive TAU, independently of their participation in the aforementioned specific interventions.

TBM will be delivered by study-nurses, iFD-survive telephone-guidance will be delivered either by nurses or psychologists, and the SAM programme will be delivered by clinical psychologists. In any case, all health professionals who will be delivering the study interventions will receive specific training. TBM will require a 5-hour training, the iFD-Survive phone guidance will require assistance to an 8-h workshop, while the SAM programme will require attendance to a 16-h workshop.

Outcome measuresPrimary outcomeThe primary outcome is probability of presenting a subsequent suicidal attempt captured across assessment points. In addition to the participant's study assessments, medical records will be consulted to complement and confirm the information provided at the different assessment points.

Secondary outcomesClinician reported outcomesSocio-demographic and clinical data including level of education, marital and employment status, income and concomitant medications, will be collected using an ad-hoc clinical interview. Suicidal ideation and behaviour will be also assessed with the Columbia Suicide Rating Scale (C-SSRS).33 The C-SSRS is a clinician-administered suicidal ideation and behaviour rating scale that assesses severity and intensity of suicidal ideation, types of suicidal behaviour, and lethality of suicide attempts at time points and over time points. The C-SSRS has a baseline version to be used at the first assessment point and a “since last visit” version that captures suicidal ideation and behaviour since the most recent previous assessment. Adherence to the pharmacological treatment (if applicable) will be assessed using the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS),34 and mental health diagnosis will be explored using the International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI).35

Participant reported outcomesThe following measures will be used to explore secondary outcomes.

- 1.

The Brief Symptoms Inventory (BSI)36 covers different symptom dimensions: somatization, obsession-compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation and psychoticism; and three global indices of distress: global severity index, positive symptom distress index, and positive symptom total.

- 2.

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)37 that rates the frequency of the depressive symptoms during the last 2 weeks using a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) will be used.

- 3.

The General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)38 will be used to assess worry and anxiety symptoms. Each item is scored on a four-point Likert scale (0–3) with total scores ranging from 0 to 21 with higher scores reflecting greater anxiety severity.

- 4.

The Barrat Impulsivity Scale (BIS-11)39 is a 30-item questionnaire that measures three aspects of impulsivity: (1) motor impulsiveness, (2) attentional impulsiveness, and (3) non-planned impulsiveness.

- 5.

The EuroQoL-5D40 is an instrument to assess health-related quality of life. It consists of two parts: a self-reported description of health problems into five dimensions and a Visual Analogue Scale corresponding to the current state of the subject's health. The lowest extreme (0) corresponds to the worst imaginable health state, and the highest extreme (100) represents the best imaginable health state.

- 6.

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-SF),41 will be used to collect childhood traumatic experiences retrospectively and across five subscales: sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect and emotional neglect.

- 7.

The Acquired Capability for Suicide Scale-Fearlessness about Death (ACSS-FAD)42 will be used to assess levels of the acquired capability for suicide. It is a seven-item self-report measure which uses a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all like me) to 4 (very much like me).

- 8.

The Reflective Functioning Questionnaire43 8-item version, will be used to measure reflective functioning, an expression of mentalizing processes. The instrument separately addresses the levels of both certainty and uncertainty about one's own mental processes.

- 9.

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)44 will be collected for participants under 18 years old. It comprises 5 scales of 5 items each evaluating: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationships problem and prosocial behaviour.

Spanish validated adult or young-versions of each scale would be used as appropriate. Safety endpoints: all adverse events will be collected up to the study final visit (month 12). A summary of the outcome measures and their timing is provided in Table 2.

Sample sizeA priori sample size estimation to study outcomes was conducted. First, the minimum requirement is over 500 participants within the cohort, under a structural equation modelling approach.45 More specifically, an optimal ratio cases/parameter to be estimated should be ensured (i.e., a ratio of 20:1) to visualize an effect size of at least, ω2=.03 and alpha=.05, to preserve acceptable levels accuracy of fit indexes. Sample size demands on survival models (e.g., Cox regression) are much more flexible (especially when a linear relationship can be depicted within predictors (e.g., depressive symptoms and suicide ideation).

In terms of RCT sample size, an estimation under simpler statistical approaches (linear models, such as analysis of variance) was also conducted. A medium effect size was considered to uncover differences between groups across follow-up. A confidence level of α=.05 and power of 1−β=.80 were kept. A between-wave correlation of .30 was assumed. The sample size was estimated for visualizing a time*group effect (e.g., the treatment delivery leads to changes in markers over follow-up), taking into consideration that we have three intervention groups within a model of repeated-measure analysis of covariance. Moreover, it expects to introduce up to three covariates. As a result, calculations stated that the sample should be made up of 158 participants. When considering a drop-out rate of over 37%, a sample of 218 participants is needed. The RCT with adolescents will comprise a number of participants (lower than those enrolled in the adults’ RCT) in accordance with the a priori sample size estimation and considering the low proportion of adolescents who visit an emergency department due to suicide attempt.45,46

RandomizationStratified randomization algorithms will be used to assign participants to the treatment arms, considering digital literacy, participant age and depression symptoms (PHQ-9 scores). First, adult participants will be matched in terms of depression scores (i.e., approximately the same proportion of individuals with depression and without depression would comprise each study group). Also, a 2-1-1 algorithm will be implemented (participants having twice the chance to be assigned into a control group than the other conditions).

Adolescent participants will be assigned to either the SAM or the control condition (TAU), under a 1-1 algorithm. All the participants will be randomized using ePRO which is an online, randomization service. Allocation concealment will be ensured, as the service will not release the randomization code until the patient has been recruited into the trial, which takes place after all baseline measurements have been completed.

Assessments regarding clinical improvement will be conducted by a researcher blinded to treatment allocation. Due to the nature of the interventions neither participants or staff can be blinded to allocation.

Statistical analysis planMixed-effects Cox regression models will be used to study the cumulative incidence of suicide reattempting and time between attempts during follow-up among study participants, considering relevant covariates (e.g., sex, age, history of mental disorders). The baseline profile of re-attempters will be studied by means of latent class analysis. The course of symptoms will be modelled by means of latent growth curve analysis to uncover overall trends over the follow-up. Latent class mixed modelling will be used to examine the hidden person-specific trajectories of symptoms that lead to suicide re-attempts. Influence of the identified trajectories on suicidal reattempting and time between attempts will be examined by means of mixed-effects Cox regression, considering the effects of relevant covariates.

Intention to treat (ITT) analyses with multiple imputation of missing cases will be conducted. Initially, basal characteristics of the individuals in each treatment arm will be investigated in order to identify possible baseline-differences to control in ulterior analyses. Cox regression will be used to study longitudinal trends in suicide re-attempting and time between re-attempts, between RCT groups. Hierarchical mixed-effect logistic regression will be used to study the profiles of individuals (in terms of sociodemographic and clinical features) who re-attempt and those who do not. Multigroup latent curve analysis will be used to study the trajectory of psychiatric symptoms between treatments across the RCT.

EthicsThis protocol and the informed consent forms have been reviewed and approved by the sponsor and the institutional review boards (IRBs) and ethical committees (ECs) at each participating site with respect to compliance with applicable research and human subjects’ regulations. The investigator will make progress reports to the IRBs/ECs.

Any modifications to the protocol which might impact on the conduct of the study will require a formal amendment to the protocol and will require approval by the ECs/IRBs prior to implementation. A delegated member of the research team will introduce the study to the patient, will give information sheets to discuss the study with the participants and their legal guardians (in the case of participants under 18 years old). Children and teenagers will receive information suitable for their ages. Consent will be obtained independently for participation in the cohort study and optional procedures (RCTs).

Dissemination plansThe Publications Committee will review all publications and will report to the Steering Committee. Study results will be written for publication following completion of study data collection and data analyses.

DiscussionSuicide prevention is a priority for public health services. Nevertheless, a comprehensive approach and understanding of suicide is still lacking. The SURVIVE study described here will evaluate, for the first time, the incidence of suicide and its most prevalent risk factors in a large cohort of Spanish participants. If successful, the trial will provide an exhaustive population-based register of suicidal behaviour and will allow the development and validation of risk predictive models, which are fundamental steps towards efficient public policies in regards to suicide prevention. The SURVIVE trial also includes three- nested RCTs that will allow us to test different secondary prevention programmes against TAU. This comparison will shed light on the specific effects of each intervention programme (i.e., TBM, iFD-Survive and SAM) and will allow us to investigate if different participant's profiles are associated with better treatment-response. Currently, specific and tailored actions to provide follow-up care of individuals at high risk is uneven across the territory. To mitigate the risk associated to differences between TAU across participant sites, analysis will be controlled for this variable. In addition, pre-treatment differences between groups will be explored, and controlled if necessary.

Our study aims to further advance on the fight against suicide with the full support of large public health providers.

Trial statusRecruitment for the cohort is expected to start in mid 2020. Recruitment for the iFD-Survive and SAM intervention is expected upon finalizing materials.

Trial registrationProtocol versionV3.0 Dated 06 April 2020.

SponsorInstituto Mar de Investigaciones Médicas (IMIM-PSMar).

ContributorsVP conceived of the idea and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. ME, and AT prepared the first complete draft of the manuscript. ADLTL prepared the statistical analysis plan. JB, CLS, MDM, IG, MPLP, BRV, and MRV helped to conceive the idea and aided in the interpretation of results. The SURVIVE group has contributed to the design of the study and will assist in recruitment activities. All authors approved the final article.

FundingThis work was supported by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISC-III)-FEDER: Hospital del Mar (PI19/00236), Universidad de Oviedo. ISPA. SESPA. CIBERSAM (PI19/01027), Hospital Clínico San Carlos (PI19/01256), Hospital Universitario Araba-Santiago. Universidad del País Vasco. CIBERSAM (PI19/00569), La Paz Institute for Health Research (IdiPAZ) (PI19/00941), Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí de Sabadell (PI19/01484), Hospital Clínic, IDIBAPS (PI19/000954). Hospital Virgen del Rocío de Sevilla (PI19/00685).

Conflict of interestsThe rest of the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The following are members of SURVIVE: José Luis Ayuso-Mateos, Teresa Bobes-Bascarán, María-Fe Bravo-Ortiz, Manuel Canal Rivero, José Luis Carrasco, Patricia Diaz-Carracedo, Jessica Fernández-Sevillano, Elena Garcia-Ligero, Marina Garriga, Itxaso González-Ortega, Ana González-Pinto, Eduardo Jiménez-Sola, Luis Jiménez-Treviño, Elvira Lara, Manuel Jesus Martínez Lopez, Roberto Mediavilla, Blanca Mellor-Marsá, Igor Merodio Ruiz, Diego Palao, Andrés Pemau, Adrián Perez-Aranda, Dolors Puigdemont, Estela Salagre, Marta Sanchez Batanero, Elisa Seijo-Zazo, Eduard Vieta, Antonia Villarrasa Millán.

JB wants to thank financial support from the Government of the Principality of Asturias PCTI-2018-2022 IDI/2018/235, the CIBERSAM and Fondos Europeos de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER). ME has a Juan de la Cierva research contract awarded by the ISCIII (FJCI-2017-31738). VP, ME, and AT want to thank unrestricted research funding from “Secretaria d′Universitats i Recerca del Departament d′Economia i Coneixement (2017 SGR 134 to “Mental Health Research Group”), Generalitat de Catalunya (Government of Catalonia). IG has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following identities: Angelini, AstraZeneca, CasenRecordati, Ferrer, Janssen Cilag, and Lundbeck, Lundbeck-Otsuka, SEI Healtcare, FEDER, Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement (2017SGR1365), CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya, Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI16/00187, PI19/00954).