The Adult Attachment Questionnaire-Revised and its psychometric properties are presented for dimensional and categorical evaluation of adult attachment style. Eight items were added to the original questionnaire (CAA; Melero and Cantero, 2008) that expanded avoidance dimension assessment and sensitivity evaluation. The exploratory factor analysis EFA led to 35 items grouped in 4 affective dimensions. (1) Anxiety: Need for approval, negative self-esteem, fear for rejection/abandonment and relationship anxiety; (2) Socioemotional competence: Emotional openness, sensitivity, and confidence; (3) Avoidance: Self-reliance and emotional discomfort with intimacy, and (4) Anger: Resentment, anger and intransigence. The cluster analysis confirmed the categorization of the 4 styles of attachment described by Bartholomew (Bartholomew and Horowitz, 1991). The questionnaire showed satisfactory levels of reliability and validity.

The increased vulnerability to pathology of individuals with insecure attachments1 has led increasing numbers of mental health professionals to evaluate attachment style in their everyday clinical practice. In his Attachment and Loss trilogy, Bowlby2,3 defined attachment as an innate biological system with a clear adaptive function that regulates feelings of discomfort caused by environmental stress. Attachment style, and most especially internal mental models2,4 are key factors in comprehending the dynamics of personal relationships, in emotion management and in stress regulation strategies. Based on the two dimensions claimed by Bowlby2 (model of self and model of others), theoretical model of Bartholomew and Horowitz,5 proposed a four-group model of adult attachment styles: dismissing, secure, preoccupied and fearful (Table 1).

Defining characteristics of adult attachment styles.

| Internal working model | Emotional regulation strategies | Intimate relationships dynamic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dismissing | |||

| Negative model of others (distrust), positive model of self5Inability to use attachment figures efficientlyHigh self-esteem derived from competences (skills) but not from a positive consideration of others27Goal oriented, need for achievement20 | Deactivated attachment system2Distancing of signals linked to attachment and threats24Organized strategies: self-sufficiency and independence5Cognition-centredRationalization | Denial and avoidance of attachment needs, emotional self-sufficiency as defensive strategies18,20, low emotional expressiveness and self-disclousureAvoidance of intimacy, discomfort with closeness.Defensively rationalizing and excluding information connected to attachment24Not seeking others' support to bear emotional stress | |

| Secure | |||

| High on self and others' confidence (positive mental models)2,3,5Use of attachment figures as the a secure baseHigh self-esteem based on the internalization of the positive consideration of others27People-oriented20 | Balanced activation of the attachment system when a threat is perceivedOrganized strategies: balanced autonomy-intimacySeeks proximity as a functional strategy for emotional regulation24 | Comfort in situations involving intimacy, commitment and affectionConstructive and assertive problem solving strategies, taking what is best for the relationship into account19 | |

| Preoccupied | |||

| Positive mental model of others and negative model of self5Inability to use attachment figures efficiently due to uncertainty about their availability and accessibilityNeed for approval, low autonomy, dependency Fear of abandonmentPeople-oriented20 | Hyperactivation of the attachment system. Hypervigilance of signals associated with attachment and threats24Organized strategies: exacerbated emotion to gain the attention and closeness of the attachment figureEmotion-centredRumiation | Desire for extreme intimacy.High levels of conflict23Jealousy, demanding behaviour, a strong need for proximity and attentionIntrusive | |

| Fearful | |||

| Negative mental models of self and others5Inability to use attachment figures efficientlyNeed for approval. Expectation and fear of being hurt or rejected5People-oriented20 | Combination of attachment system hyperactivation and deactivation strategies8,24Disorganized strategies. Desire for intimacy but mantains physical and emotional distance as a defensive strategyIncreased vulnerability to pathology1 | Desire for intimacy, but avoids proximity due to their fear of rejection and distrust of others5Low self-openness, high level of worry and rumiationLack of social skills, socially avoidant | |

Regarding the evaluation of attachment, from the work of Fraley and Waller6 and the creation of the “Experiences in Close Relationships” (ECR)7 questionnaire, measures that assess attachment in a dimensional way are recommended. Research in this area has repeatedly detected the existence of two affective dimensions: 1) a dimension that is equivalent to the “model of self”,2 the negative extreme of which is associated with anxiety, dependency, fear of rejection and abandonment, and 2) a dimension which is equivalent to the “model of others”,2 the negative extreme of which is associated with avoidance, discomfort with intimacy, and emotional self-sufficiency. The first dimension, anxiety, reflects the tendency towards hyperactivation of the attachment system with the aim of minimizing the distance of the attachment figure which is considered to be inconsistent. The second dimension, avoidance, refers to the use of deactivation strategies which aim to maximize the distance from the attachment figure, which is considered to be threatening or potentially rejecting from an emotional point of view.8,9

Nevertheless, in spite of the efficacy of the bidimensional assessment by ECR, Bäckström and Holmes10 conclude that it is important for adult attachment evaluation instruments to include assessment of the concept of security as well as the classical dimensions of avoidance and anxiety. We also consider it to be essential to differentiate attachment emotional regulation strategies between the highly avoidant groups (fearful and dismissing). While a fearful strategy avoids intimacy as a defense against the fear of possible rejection, the avoidance of dismissing stems from a consistent strategy that centres on emotional self-sufficiency. On the other hand, there is still a demand for categorical evaluation, especially within the clinical context.11 We therefore agree with Cummings12 when he points out the need to continue progressing in the creation of instruments that are able to perform both types of evaluation.

Melero and Cantero13 tried to overcome these limitations by developing the “Cuestionario de Apego Adulto” (CAA) within the Spanish context. This questionnaire evaluates a combination of 4 affective dimensions whose combination makes it possible to obtain a diagnosis of attachment style. Due to the increasingly widespread use of the CAA in the field of mental health, we believe that it would be timely to resolve some of the limitations of the original questionnaire, improving its diagnostic capacity. We therefore add 8 items to the 40 items contained in the CAA. These new items broaden the evaluation of the avoidance dimension and include the evaluation of sensitivity. This work therefore has the aim of analysing the psychometric properties of the revised version of the Cuestionario de Apego Adulto (CAA-r) and its capacity to assess the dimensions and typologies of adult attachment.

MethodSubjectsThe subjects were 921 adults of the Comunidad Valenciana: 419 men (45.5%) and 502 women (54.5%) ranging in age from 18 to 65 years old (M=28.3, DT=10.4). Regarding their educational level, 8.7% (n=79) had studied to an elementary level, 49.1% (n=443) had finished secondary school and 42.2% (n=381) had received higher education. In terms of their work status, 48.2% (n=444) were students, 29.9% (n=275) were in active employment, 4.7% (n=43) were unemployed, 1.0% (n=9) did housework and 2.2% (n=20) were retired/pensioners.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Valencia University. The subjects were informed of the objectives and procedures of the study as well as the voluntary nature of participation, using a written document, and they signed the corresponding consent form. The subjects were selected from the general population using non-probabilistic methods based on gender quotas and snowball sampling.

Instruments- •

Cuestionario de Apego Adulto (CAA)13. The CAA is an adult attachment evaluation questionnaire that was constructed and adapted to the Spanish population. It is composed of 40 items with a 6-point response scale (1: strongly disagree; 6: strongly agree). It assesses 4 affective dimensions: 1) low self-esteem, the need for approval and fear of rejection (13 items); 2) hostile conflict resolution, resentment and possessiveness (11 items); 3) emotional expression and comfort in relationships (9 items), and 4) emotional self-sufficiency and discomfort with intimacy (7 items). The reliability indices (Cronbach's α) were 0.86, 0.87, 0.77 and 0.68, respectively. Eight new items were added to the previous 40 items of the CAA to evaluate avoidance strategies (5 items) and emotional sensitivity (3 items).

- •

Cuestionario de Relación (Relationship Questionnaire) (CR)5. This questionnaire gives a categorical measurement of attachment by means of the obligatory choice of one of 4 paragraphs that describe the mental models of the four attachment styles: secure, fearful, preoccupied and dismissing. At a psychometric level studies have confirmed its validity and test-retest stability.14

- •

Experiencias en las relaciones íntimas (Experiences in Close Relationships) (ECR)7, adapted to the Spanish population by Alonso-Arbiol et al.15 (ECR-S). This self-reporting scale is composed of 36 items (1: totally disagree; 7: totally agree) and it evaluates two insecurity scales: avoidance (18 items) and anxiety (18 items). The Spanish adaptation scored 0.87 for avoidance and 0.85 for anxiety in Cronbach's alpha. This study obtained similar internal consistency scores of 0.87 and 0.86, respectively.

After checking the fit of the items, and given the ordinal nature and deviation from normalcy of some data, the decision was taken to perform an exploratory factorial analysis (EFA) of the polychoric correlation matrix using the unweighted minimum squares estimation method. Promax oblique rotation was used. Two criteria were used to determine the number of factors to be extracted: parallel analysis (PA) and the Minimum Average Partial test (MAP). The invariance of measures was analysed according to sex using multigroup confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA). Successive parameter restriction steps were followed and they were subjected to the configural invariance test (M1), metric invariance (M2), scaled invariance (M3) and residual or strict invariance (M4). The internal consistency of the scales was analysed using ordinal alpha coefficients.

K means clustering was used to obtain the typologies of adult attachment. Finally, converging validity was checked (for the ECR and CR scales) using ANOVAS and correlational analysis. Version 24.0 of the IBM SPSS, FACTOR 10.8.02 and Mplus 6.11 statistical packages were used.

ResultsExploratory factorial analysisThe measurement of sampling fit obtained using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin index (KMO=0.88) and Bartlett's sphericity test (χ2 (595)=9205.8, P<.001) showed that the data matrix used for factorial analysis was suitable. The MAP criterion and the result of PA showed that 4 components was the optimum number of factors for extraction. 13 items were eliminated as they had similar saturations in 2 or more factors (4 items), as they had a factorial loading of less than 0.40 (6 items) or because of theoretical criteria (3 items). Of the items that were eliminated, 10 belonged to the original version and 3 were items that had been added. The definitive factorial solution was composed of 35 items grouped in 4 factors, which explained 45.9% of the variance. The goodness of fit indexes supported the factorial solution obtained with a GFI score of 0.98 and a RMSR of 0.04. The first factor, denominated “Anxiety”, explained 22.99% of the variance and grouped 11 items linked to the need for approval, a negative self-image, fear of rejection and abandonment and anxiety caused by relationships. The second factor, “Socioemotional competence”, explained 10.42% of the variance and grouped 9 items linked to emotional openness, sensitivity and confidence. The third factor, “Avoidance”, explained 6.75% of the variance and included 9 items that assessed emotional self-sufficiency and discomfort with closeness. The fourth factor was denominated “Anger” and included 6 items which measured resentment, anger and intransigence, explaining 5.74% of the variance (Table 2). Factors 1, 3 and 4 are manifestations of insecurity in attachment, and factor 2 is an expression of security. The final questionnaire and standards for the general population are included in appendices 1 and 2, respectively.

Average, standard deviation and factorial saturation in the final factorial solution.

| Item | Av | SD | Factorial saturation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety: need for approval, negative self-image, fear of rejection /abandonment and anxiety about relationships | |||

| 15. I believe I don't measure up to others | 2.51 | 1.45 | 0.76 |

| 23. I am very sensitive to others' criticisms | 3.79 | 1.45 | 0.75 |

| 32. I care a lot about what other people think of me | 3.41 | 1.45 | 0.73 |

| 46. I need to make sure that I'm really important to others | 3.54 | 1.41 | 0.63 |

| 37. I would like to change lots of things about myself | 3.41 | 1.47 | 0.59 |

| 7. I feel inferior compared to others | 2.17 | 1.26 | 0.55 |

| 42. I feel I need more care and/or attention than most people do | 2.38 | 1.34 | 0.53 |

| 28. It's difficult for me to make a decision unless I know what others think about it | 2.84 | 1.41 | 0.50 |

| 19. I like having a romantic relationship but I'm afraid of being rejected | 3.16 | 1.64 | 0.51 |

| 11. When I have a problem with someone, I can't stop thinking about it | 4.37 | 1.32 | 0.48 |

| 44. I find it difficult to end a relationship because I'm scared of not being able to face it | 2.78 | 1.60 | 0.44 |

| Socioemotional competence: emotional openness, sensitivity and confidence | |||

| 48. I feel that people often trust me and value my opinions | 4.78 | 0.99 | 0.66 |

| 45. Other people think I'm an open person; it's easy to get to know me | 4.45 | 1.34 | 0.64 |

| 41. I usually grasp other people's feelings, even if they don't express them or do it subtly | 4.45 | 1.18 | 0.57 |

| 29. When I have a problem with someone, I try to talk to them to solve it | 4.85 | 1.08 | 0.54 |

| 1. It's easy for me to express my feelings and emotions | 4.52 | 1.32 | 0.46 |

| 6. I feel comfortable at parties or social gatherings | 4.77 | 1.21 | 0.49 |

| 18. I easily become aware of others' need for help or comfort | 4.64 | 1.25 | 0.54 |

| 25. I have confidence in myself | 4.63 | 1.22 | 0.47 |

| 36. When I have a problem, I tell it to someone I trust | 5.05 | 1.17 | 0.42 |

| Avoidance, emotional self-sufficiency and discomfort with intimacy | |||

| 34. I like being in a romantic relationship, but at the same time I find it a burden | 2.36 | 1.44 | 0.81 |

| 26. I wouldn't have a stable relationship because I don't want to lose my autonomy | 1.72 | 1.16 | 0.83 |

| 8. I never fully commit to my relationships | 1.85 | 1.31 | 0.77 |

| 21. I need to distance myself from someone who is dependent on me | 2.63 | 1.32 | 0.58 |

| 40. When I hug or kiss someone I care about, I'm tense and part of me feels uncomfortable | 1.66 | 1.12 | 0.60 |

| 24. I prefer it when people close to me don't know how I feel inside | 2.83 | 1.53 | 0.48 |

| 33. I prefer to be alone instead of engaging in social relationships | 2.17 | 1.37 | 0.46 |

| 12. Sometimes I feel the need to distance myself when someone important to me is sad and/or crying | 2.04 | 1.23 | 0.45 |

| 4. I would rather not share my intimate feelings or thoughts with people that are important to me | 2.45 | 1.53 | 0.47 |

| Anger: resentment, anger and intransigence | |||

| 5. I agree with the principle “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth” | 2.46 | 1.52 | 0.64 |

| 27. I'm resentful | 2.80 | 1.53 | 0.60 |

| 2. I don't accept others' opinions if I think I'm right | 3.26 | 1.50 | 0.57 |

| 31. When I'm angry at someone, I try to make them be the one to apologize | 2.75 | 1.34 | 0.48 |

| 9. If a family member or a friend contradicts me, I easily get angry | 2.78 | 1.37 | 0.49 |

| 22. I really insist on my point of view to be accepted when there are different opinions | 3.43 | 1.37 | 0.46 |

The numeration of the items corresponds to the initial version of the CAA-r with 48 items.

The hypothesis of measurement invariance depending on sex was tested. The goodness of fit scores for men (χ2=1,862.93; gl=554; χ2/gl=3.363; CFI=0.805; RMSEA=0.075 [CI 90%: 0.071-0.079]; WRMR=1.777) and for women (χ2=2362.12; gl=554; χ2/gl=4.264); CFI=0.780, RMSEA=0.080 [CI 90%: –0.077 to 0.084]; WRMR=1.986) were not fully satisfactory, with CFI values below 0.90. Nevertheless, according to Lloret et al.16, AFC is an excessively restrictive technique when it is applied to complex measurements. The length and multidimensional nature of the measurement hinder fit due to the inevitable existence of smaller crossed loadings with the other factors.16,17 The cut-off points for a good fit should therefore not be interpreted strictly, and the complexity of measurements should not be reduced at the cost of predictive validity and theoretical relevance.17

Measurement invariance was calculated by testing the configural invariance models (χy=4,217.89; gl=1,113; χy/gl=3.79; CFI=0.791; RMSEA=0.078 [CI 90%: 0.075-0.080]; WRMR=2.667), metric invariance (χy=4,199.66; gl=1,144; χy/gl=3.67; CFI=0.794; RMSEA=0.076 [CI 90%: 0.074-0.079]; WRMR=2.693), scale invariance (χy=4,425.11; gl=1,275; χy/gl=3.47; CFI=0.788; RMSEA=0.073 [CI 90%: 0.071-0.076]; WRMR=2.837) and residual invariance (χy=4,359.54; gl=1,309; χy/gl=3.33; CFI=0.795; RMSEA=0.071 [CI 90%: 0.069-0.073]; WRMR=2,882). Once the baseline model had been established (M1), the next level of restriction (M2: metric invariance) gave rise to small changes in the fit indices (ΔCFI=0.003, ΔRMSEA=0.002); the level of metric invariance was therefore satisfactory. In the following level of restriction, when M2 and M3 were compared (scale invariance) a non-significant difference was also obtained in the CFI and the RMSEA (ΔCFI=0.006, ΔRMSEA=0.003). Finally, residual or strict invariance (M4) compared with scale invariance (M3) also showed slight differences in the CFI and the RMSEA (ΔCFI=0.007, ΔRMSEA=0.002). Given that at all levels of invariance the difference in the CFI and RMSEA was less than 0.01 and 0.015, respectively, the hypothesis of measurement invariance depending on sex was accepted. I.e., the factorial structure of the CAA-r did not vary between men and women.

Reliability analysisThe ordinal alpha statistic showed a suitable degree of internal consistency of the scales, with values of 0.86 in the “Anxiety” factor, 0.79 in the “Socioemotional competence” factor, 0.85 in the “Avoidance” factor and 0.75 in the “Anger” factor.

Cluster analysisK means clustering analysis was performed to identify groups of adult attachment according to the direct scores obtained in the 4 affective dimensions (Table 3).

Average and standard deviation of the direct scores in each cluster.

| Cluster 1Dismissing (A)Av (SD) | Cluster 2Secure (B)Av (SD) | Cluster 3Preoccupied (C)Av (SD) | Cluster 4Fearful (D)Av (SD) | Cohen's d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1:Anxiety | 3.08 (0.57)(moderate to low) | 2.48 (0.62)(low to very low) | 3.60 (0.68)(high to very high) | 4.36 (0.63)(high to very high) | D>B. d=3.01D>A. d=2.13D>C. d=1.16C>B. d=1.72C>A. d=0.83A>B. d=1.01 |

| Factor 2:Socioemotional competence | 4.19 (0.58)(low to very low) | 5.05 (0.52)(high to very high) | 4.75 (0.54)(moderate to low) | 4.17 (0.76)(very low to low) | B>A. d=1.56B>D. d=1.35B>C. d=0.57C>D. d=0.88C>A. d=1.00 |

| Factor 3:Avoidance | 2.84 (0.58)(high to very high) | 1.67 (0.43)(low to very low) | 1.88 (0.44)(low to very low) | 3.54 (0.84)(high to very high) | D>B. d=2.80D>C. d=2.48D>A. d=0.97A>B. d=2.29A>C. d=1.86C>B. d=0.47 |

| Factor 4:Anger | 2.83 (0.65)(moderate to high) | 2.22 (0.61)(low to very low) | 3.56 (0.69)(high to very high) | 4.02 (0.84)(high to very high) | D>C. d=0.60D>A. d=1.58D>B. d=2.45C>A. d=1.09C>B. d=2.06A>B. d=0.97 |

| Cases | 199 (21.61%) | 368 (39.96%) | 251 (27.25%) | 103 (11.18%) |

In brackets and italics: range of expected score based on standards and the theoretical framework of reference.

Cluster 1 grouped subjects who obtained a high score for “Avoidance”, a low score for “Socioemotional competence” and moderate scores for “Anxiety” and “Anger”. This profile corresponded to the dismissing attachment profile (21.6% of the subjects). Cluster 2 identified a profile characterized by higher scores for “Socioemotional competence” and low scores for the other dimensions of insecurity, characteristic of a secure attachment profile (39.96%). Cluster 3 described a profile characterized by high scores for “Anxiety” and “Anger”, a low score for “Avoidance” and a moderate score for “Socioemotional competence”. These characteristics defined a preoccupied attachment profile (27.25%). Finally, cluster 4 grouped subjects who had very high scores for “Anxiety”, “Avoidance” and “Anger”, and very low scores for “Socioemotional competence”. This profile corresponded to the fearful attachment style (11.18%). Table 3 shows the size of the effect of the differences between groups when evaluating its magnitude.

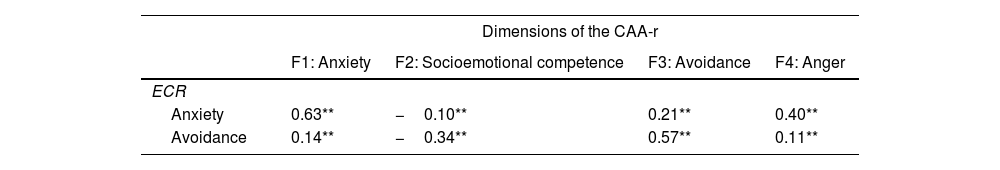

Convergent validityTo evaluate the convergent validity of the dimensional evaluation of the CAA-r, correlational analyses were carried out between the ECR scores for avoidance and anxiety and the scores for the four dimensions of the CAA-r. The ECR dimensions of anxiety and avoidance correlated significantly in a positive way with the factors of “Anxiety”, “Avoidance” and “Anger”, and they correlated negatively with “Socioemotional competence”. Additionally, 4 ANOVAS were performed using the attachment categories of the CR as the grouping variable, with the scores of the CAA-r dimensions as the dependent variable. Statistically significant differences were obtained in the 4 dimensions of the CAA-r between the CR attachment groups. Post hoc tests (Sheffé) and the effect size (Cohen's d) confirmed the expected differences between the attachment groups (Table 4).

Convergent validity of the dimensional evaluation of the CAA-r.

| Dimensions of the CAA-r | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1: Anxiety | F2: Socioemotional competence | F3: Avoidance | F4: Anger | |

| ECR | ||||

| Anxiety | 0.63** | −0.10** | 0.21** | 0.40** |

| Avoidance | 0.14** | −0.34** | 0.57** | 0.11** |

| CR | Av (SD) | Av (SD) | Av (SD) | Av (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secure (B) | 2.81 (0.84) | 4.94 (0.56) | 1.92 (0.74) | 2.65 (0.91) |

| Fearful (D) | 3.49 (0.81) | 4.2 (0.68) | 2.61 (0.89) | 3.23 (0.86) |

| Preoccupied (C) | 3.79 (0.80) | 4.74 (0.67) | 2.11 (0.68) | 2.62 (0.87) |

| Dismissing (A) | 2.91 (0.75) | 4.4 (0.68) | 2.62 (0.87) | 3.04 (0.82) |

| F test | F(3.838)=62.76*** | F(3.838)=59.37*** | F(3.838)=44.76*** | F(3.838)=24.67*** |

| Post hoc. Cohen's d | C>B***. d=1.19;C>A***. d=1.13;C>D*. d=0.37;D>B***. d=0.82;D>A***. d=0.74 | B>D***. d=1.08;B>A***. d=0.88;B>C*. d=0.33;C>D***. d=0.70;C>A***. d=0.52 | D>B***. d=0.83;D>C***. d=0.63;A>B***. d=0.8;A>C***. d=0.66 | D>B***. d=0.65;C>B***. d=0.60;A>B**. d=0.44 |

Two ANOVAS were used to study the convergent validity of the categorical assessment of the CAA-r. The results showed that there were statistically significant differences in the Anxiety and Avoidance dimensions of the ECR between the attachment groups of the CAA-r. In the post hoc tests (Sheffé), the “fearful” and “preoccupied” groups scored significantly higher in the “anxiety” dimension of the ECR, with a range of Cohen's d values from 1.41 to 0.40, as did the “dismissing” and “fearful” groups in the “avoidance” dimension, with d values ranging from 1.43 to 0.47 (Table 5).

Convergent validity of the categorical evaluation of the CAA-r.

| CAA-r categories | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECR | Secure (B)Av (SD) | Fearful (D)Av (SD) | Preoccupied (C)Av (SD) | Dismissing (A)Av (SD) | F test | Post hoc. Cohen's d |

| Anxiety | 3.38 (0.82) | 4.64 (0.97) | 4.27 (0.92) | 3.67 (0.71) | F(3.814)=82.44*** | D>B***. d=1.41;D>A***. d=1.15;D>C*. d=0.40;C>A**. d=0.73;C>B**. d=1.02;A>B*. d=0.38 |

| Avoidance | 2.43 (0.77) | 3.62 (0.89) | 2.43 (0.77) | 3.21 (0.84) | F(3.814)=84.43*** | D>B***. d=1.43;D>A*. d=0.47;D>C***. d=1.42;A>B***. d=0.97;A>C***. d=0.97 |

These data confirm the convergent validity of the dimensional and categorical evaluation of the CAA-r.

DiscussionThe CAA-r validation study confirms the existence of combinations of 4 factors or emotional dimensions that can be subjected to categorical evaluation that identifies the 4 attachment styles described by Bartholomew and Horowitz.5

Dimensional evaluation of the CAA-rThe four factors or scales of the CAA-r make it possible to undertake a dimensional assessment of adult attachment. The first dimension, “Anxiety”, evaluates preoccupation with relationships, rumiation on relational problems, low self-confidence and a negative self-image, fear of rejection, need for approval, and anxiety about relationship issues. This affective dimension of insecurity is associated with emotional regulation hyperactivation strategies. This hyperactivation stems from insecurity about the availability and accessibility of significant individuals, which together with a negative self-image, leads to an exacerbation of the emotion and approval-seeking.5,18

The second dimension of “socioemotional competence” groups items that evaluate emotional openness, constructive strategies for the resolution of interpersonal problems, appreciation of social relationships, confidence in oneself as well as in others, and the capacity for empathy and sensitivity. This dimension chiefly characterizes individuals with secure attachment, as it involves primary emotional regulation strategies. Significant others are valued as accessible, sensitive and available. Regarding sensitivity, Ainsworth underlined its importance in the development of secure attachment in infants, and it has been consistently associated with the quality of relationships in adult age.18,19 Obtaining this category would be consistent with the importance of “capturing the essence of security as originally conceived by Bowlby” (Bäckström and Holmes,10 p. 142).

The third dimension, “Avoidance”, corresponds to insecurity and covers emotional regulation strategies involving deactivation that preferentially entail physical and emotional withdrawal. It groups items that describe problems in helping others, low level of commitment, avoidance of intimacy a preference for solitude and conflict resolution strategies that are based on self-sufficiency and the absence of seeking support from others. This emotional control involves a negative concept of significant figures, who are considered to be neither effective nor useful as emotional support, giving rise to the need for self-sufficiency and/or a goal oriented attitude.5,20

Lastly, the fourth dimension of “Anger” was described by Bowlby3 as characteristic of attachments involving high anxiety, where the hyperactivation strategies used would exacerbate the expression of emotional needs, anger and hostility.21–23 This dimension of insecurity groups items which evaluate resentment, anger and intransigence. These emotions arise due to unresolved conflicts with the attachment figures,3 a high level of emotional reactivity, the need for attention and hypersensitivity to the negative opinions of others.

The results obtained in the study of the reliability and convergent validity of the four scales confirmed that the instrument has suitable psychometric properties. The affective dimensions of the CAA-r related as expected to the dimensions of avoidance and anxiety of the ECR and the attachment categories of the CR.

Categorical evaluation of the CAA-rThe evaluation of attachment style is important in clinical practice11 and in research, as it makes it possible to understand the functionality of the emotional regulation strategies used, as this is not possible by solely using dimensional evaluation. The CAA-r permits the identification of four attachment styles which correspond to the styles identified by Bartholomew and Horowitz.5

Dismissing attachment is chiefly characterized by a high level of “Avoidance” and a low level of “Socioemotional competence”. These results are consistent with those of previous studies which define this as an emotionally self-sufficient profile which is goal-oriented as opposed to personal relationships, affective coldness and discomfort with closeness.5,20,22 On the other hand, the “Avoidance” displayed by dismissing individuals is less extreme than that of those who are fearful (who struggle against feelings of dependency) because they do not need to forcibly create an emotional distance to feel safe, as their affective avoidance forms a part of a consistent and effective stress management strategy. Thus the search for support in others is excluded from their emotional regulation strategies, as instead of this they use attachment system deactivation strategies, supressing thoughts and emotions associated with it.8,24

The secure attachment style is defined by a high level of “Socioemotional competence” and low scores in the three insecurity factors. These results confirm a pattern of security which is similar to the one found in previous studies. It is characterized by a high level of self-esteem and self-confidence, a positive image of others, a low level of self-sufficiency,5 greater sensitivity in caring for others28 and constructive conflict resolution strategies.18,19 The secure style therefore has an appropriate balance between the need for ties and personal independence, activating primary attachment strategies of approach as a means of emotional regulation.24

The preoccupied attachment style is chiefly characterized by a high level of “Anxiety” combined with low “Avoidance” and high “Anger”. This attachment style involves a strong need for approval, anxiety about relationships, a negative self-image, fear of abandonment, dependency and, consistently with this, a strong seek for intimacy, attention and support. Although preoccupied attachment has been defined as sociable,5 unlike secure attachment, it seeks others due to the individual's own motivations, as they need approval and closeness, and because their self-esteem is dependent on this. According to Collins et al.,25 this focus on their own needs gives rise to an intrusive care and lack of sensitivity to others' signals. Although a preoccupied individual may be efficient at detecting the emotional state of others, they will interpret said emotions as being more negative than they really are,21 and they will be hypervigilant regarding possible threats and abandonment. Research has shown that this hyperactivation of the attachment system and the need of physical closeness gives rise to highly demanding patterns of interaction and a high level of conflict that is interpreted by the dependent individual as beneficial for the relationship.9,23 That is, the exacerbated emotion has the aim of gaining the attention and closeness of the attachment figure, although it is also the result of greater emotional reactivity and less capacity to regulate anxiety states. The preoccupied style has been associated with anxiety disorders.1,18

Lastly, the fearful attachment style is mainly characterised by high levels of “Anxiety” and “Avoidance”. I.e., it combines low self-esteem, need for approval and anxiety about relationships along with a high level of emotional avoidance and self-sufficiency as a defensive strategy. This pattern is consistent with affective disorganisation that, when faced with situations that activate the attachment system, simultaneously triggers secondary hyperactivation and deactivation strategies.24 It also appears to be characterized by a very low level of “Socioemotional competence” which indicates difficulties in expressing emotions, low sensitivity, poor social skills and a lack of confidence in self and others. In the same way as in the CAA, this profile has a high score for the “Anger” factor due to a negative concept of others, a lack of constructive problem resolution strategies and a generalized state of emotional frustration. Unlike the other attachment styles, the fearful style has disorganized emotional regulation strategies as it is unable to coherently integrate in their attachment mental model the anxiety about relationships and the need for closeness with the intense fear of potential emotional harm deriving from affective relationships. This profile has consistently been associated with increased vulnerability to physical and psychological pathologies.1 We should therefore state that scores above P90 (+2 DT) in the dimensions of anxiety and avoidance may define a disorganized attachment style. This attachment style may be considered to be an extreme form of fearful attachment26 with consequences in terms of socioemotional functioning and personal adjustments “even more destructive than might be expected from the additive effects of the two forms of insecurity” (Mikulincer and Shaver,18 p. 41).

Converging validity analysis confirmed the relationship between the attachment categories obtained in the CAA-r and the dimensions of the ECR.

ConclusionSeveral aspects of the CAA-r improved in comparison with the previous version: 1) the number of items falls to 35, making it easier to apply; 2) it shows greater sensitivity in detecting characteristics within the “Avoidance” dimension, which is fundamental in defining the dismissing and fearful styles; 3) the “Socioemotional competence” scale is reinforced with items that connect with sensitivity; 4) as Bowlby3 pointed out, the “Anger” scale appears to be a defining characteristic of fearful and preoccupied forms of attachment, and 5) the percentage of secure subjects increases in comparison with the previous versions (from 29.66% to 39.96%).

The CAA-r is a dimensional and categorical evaluation questionnaire on adult attachment, and it responds to the need to broaden bidimensional assessment (anxiety and avoidance) while including a dimension that is characteristic of secure attachment, as defined by Bäckström and Holmes.10 Following Cummings’12 recommendation, the CAA-r makes it possible to evaluate adult attachment style in a way that facilitates research and clinical practice.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.