The purpose of the present study was to characterize the education that patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus receive, and to identify differences as regards the presence of insulin therapy or not.

MethodsThis crossover, multicentre and descriptive study involved 1066 Spanish physicians who completed a questionnaire on Internet.

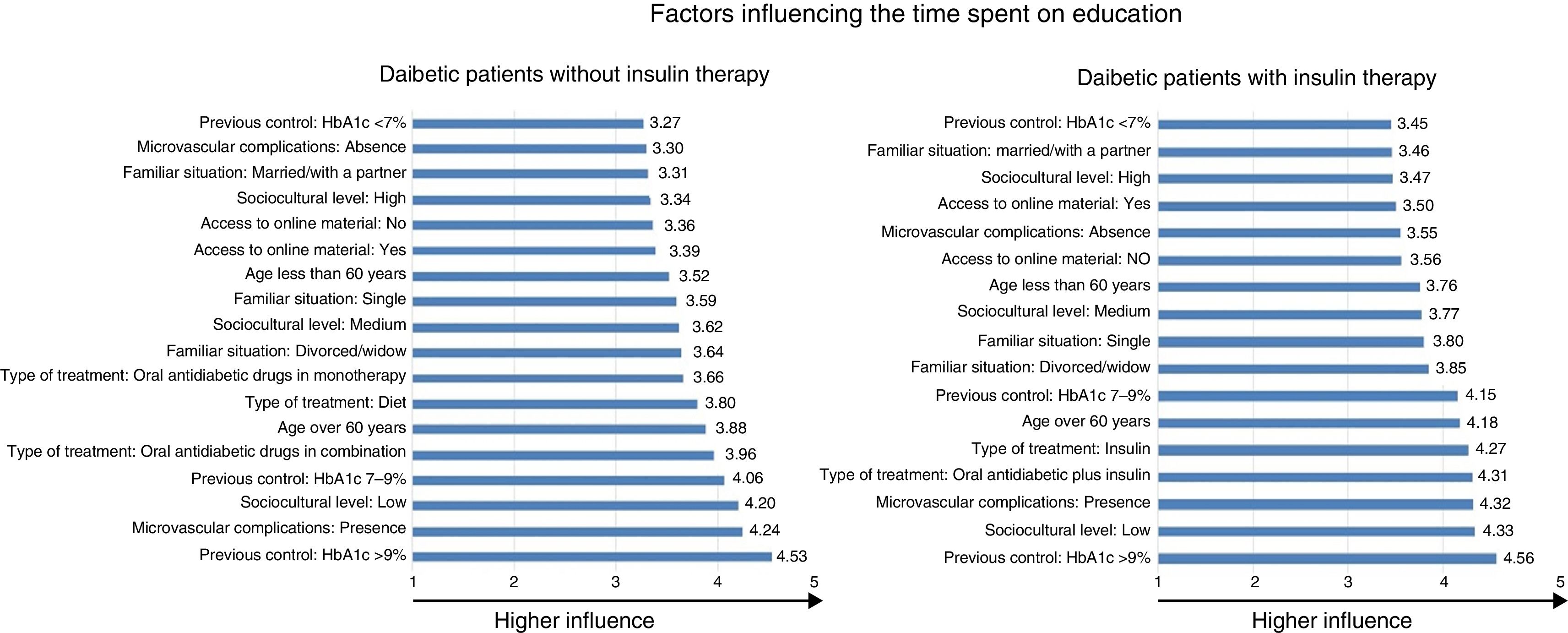

ResultsThe physicians that responded had a mean of 26.0 years of experience in healthcare, and mainly worked in a walk-in clinic in an urban area. Physicians rated the level of patient knowledge about their disease on a 5.0 point-scale. Fifty percent of them indicated that they spent between 15 and 30min in educating patients at the time of diagnosis. Previous control with HbA1c>9%, presence of microvascular complications, and a low socio-cultural level, were factors associated with spending more time in education.

ConclusionThis is the first study designed to evaluate the education provided to patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus from Spain. The time spent and the individualization of the education are important factors associated with better long-term control of the disease, and thus with the effectiveness of the clinical management.

El objetivo del presente estudio fue caracterizar la educación que reciben los pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 e identificar las diferencias existentes en función de la presencia o ausencia de terapia insulínica.

MétodosEn este estudio transversal, multicéntrico y descriptivo participaron 1.066 médicos españoles que completaron una encuesta por Internet.

ResultadosLos médicos participantes tenían una experiencia media de 26 años en atención sanitaria y principalmente trabajaban en centros de atención primaria de áreas urbanas. Los médicos determinaron el grado de conocimiento de cada paciente en relación con su enfermedad empleando una escala de 5 puntos. El 50% de los médicos indicaron que habían empleado entre 15 y 30min en educar al paciente en el momento del diagnóstico. Los niveles de HbA1c>9%, la presencia de complicaciones microvasculares y un nivel sociocultural bajo fueron los factores asociados a la necesidad de dedicar un mayor tiempo a la educación.

ConclusiónEste es el primer estudio diseñado para evaluar la educación proporcionada al paciente con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 en España. El tiempo dedicado y la individualización de la educación son factores asociados con un mejor control a largo plazo de la enfermedad y, consecuentemente, con una mayor eficacia en su manejo clínico.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is one of the most important health issues and is a burden on Healthcare National systems worldwide.1 The prevalence in Spain is approximately 13.8%, with 6.0% of cases with unknown disease.2 The annual health cost per patient is 1305€; including direct costs of treatment and complications.3 The effective management of DM requires modification of patient's lifestyle (physical activity and diet), and adherence to specific behaviors, such as medication, and medical self-care.4 The development of self-care behaviors and higher medication adherence are associated with a better glycemic control.5,6 Nevertheless, the glycemic control is not adequately achieved if the patient does not know and understand how to control glucose level in diverse situations.7,8 Patient's knowledge about their disease and treatments plays a significant role in adherence self-care, and clinical outcomes.9–11 Poor knowledge can lead to poor metabolic control and thus to the development of complications.12 Physicians and nurses are responsible for providing patient's education and improving skills required to achieve an adequate self-management.13 The communication between physician and the patient also influence the degree of adherence to treatments. A recent Spanish study (Estudio REFLEJA2), performed with 974 physicians and 1012 patients aimed to identify similarities and differences between the patient's and primary care physician's perception. This study revealed that patient's perception about the number of times physicians request information about patient's preferences and their treatment adherence is lower than perceived by physicians.14 Moreover, their perception on the role of diet and physical exercise for disease control differ significantly from physician's.15 To date, there is limited information about the quality of the education provided to patients and the tools used. The main objective of the present study was to characterize the education that T2DM patients receive and to identify differences depending on the presence of insulin therapy or not.

MethodologyThis crossover, multicenter and descriptive study involved physicians from Spain. Main criteria to participate in the study were as follows: professionally active physicians; providing health care assistance in Spain, and with a minimum experience of 2 years on patients with T2DM; and willing to participate in the study. The main objective involved the type of information that physicians provide to patients, the way that they use, and the impact on the patient. Secondary objectives were: to evaluate the type of education provided and needs regarding sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients; to identify potential differences in education regarding the presence of insulin in the treatment or not; to determine how to improve the education; to evaluate whether there are differences in the education regarding characteristics of the physician (age, primary or secondary care). Procedures were performed in accordance with guidelines established by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico Universitario San Carlos (Madrid, Spain), and the Declaration of Helsinki.

The surveyAll physicians completed a survey on Internet. The first part was related to physician's demographic information and type of practice. The second part was an attitude questionnaire composed by 5 statements. Physicians should rate every statement between 1 (totally agree) and 5 (totally disagree). The survey was in Spanish; however, in this manuscript, an English translation is provided. The third part was related to the perception of the education provided to patients, consisting in 17 questions: number of patients with diabetes not receiving insulin attending consultation per month; evaluate the degree of patient's knowledge about their pathology, rated from 1 (nothing) to 5 (much); the influence of factors (current age, age at diagnosis, sociocultural level, diabetes duration, treatment, complications, degree of control) on patient's knowledge, rated from 1 (nothing) to 5 (much); the importance of factors regarding the time spent on education (disease understanding, diet, physical exercise, adherence to treatment, side effects, complications of the disease), rated from 1 (nothing) to 5 (much); time spent on different factors, rated from 1 (much time) to 5 (less time expent). Finally, physicians have to describe how education should be (discussion with the physician during consultations, presence of a nurse, support group meetings, interaction with pharmacist, patient associations, online material, or printed material) depending on the sociodemographic characteristic of the patient.

Determination of the sample sizeTaking into account the distribution of age in physicians younger than 65 years registered in the National Board of Spain in 2014,16 and the percentage of primary care (87% from total) or secondary care physicians (13%) in the National Health System,17 the final sample size was estimated. The sample of physicians was stratified by age because the education that they provide to the patient may be influenced by their age. Therefore, the estimated sample size would allow evaluating the quality of the education provided by the physician with a precision of 3.1%, overall, and between 5.4% and 7.0%, depending on age distribution; and accepting an alpha risk of 0.05 in a bilateral contrast, in case of maximum variability. Moreover, this sample size would allow detecting differences among age groups of 14%, accepting an alpha risk of 0.05, beta of 20% in a bilateral contrast with a minimum sample of 200 individuals per group.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies (%), and continuous variables as mean and the standard deviation (SD). Comparisons of demographic characteristics of physicians (age groups) and type of care (primary or secondary) were done by using U Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests or Fisher Exact test. The statistical significance was established for P≤0.05. All statistical procedures were performed with SPSS 21.0 software.

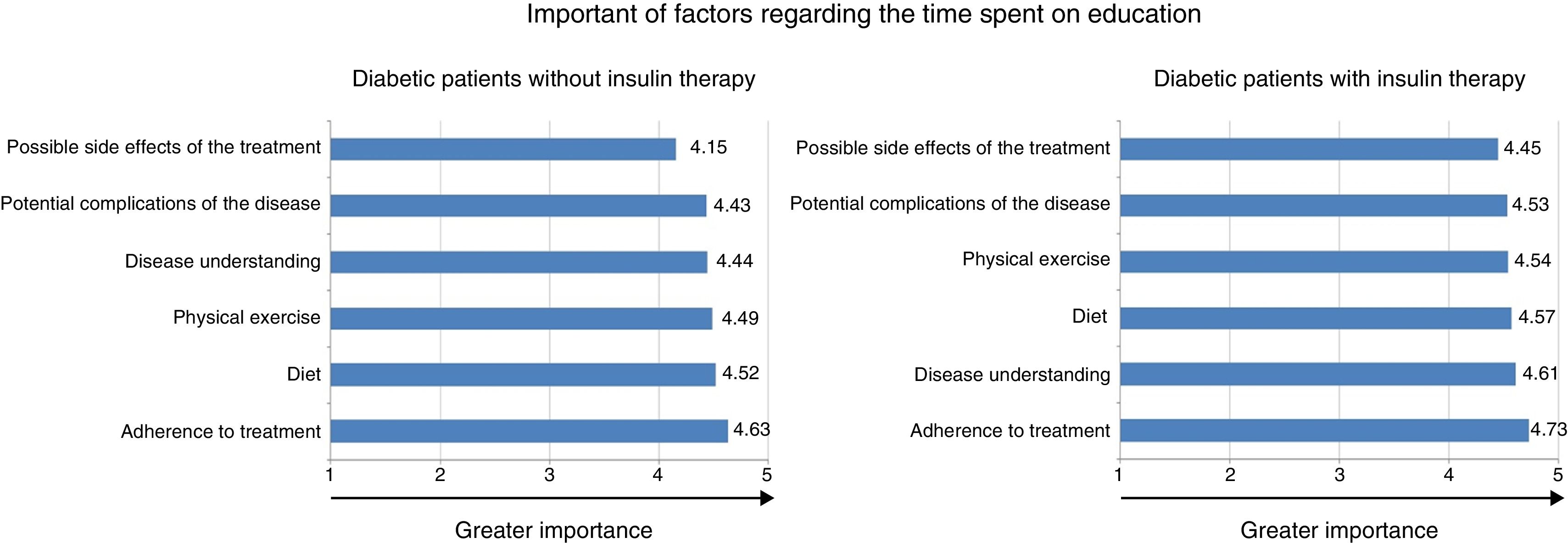

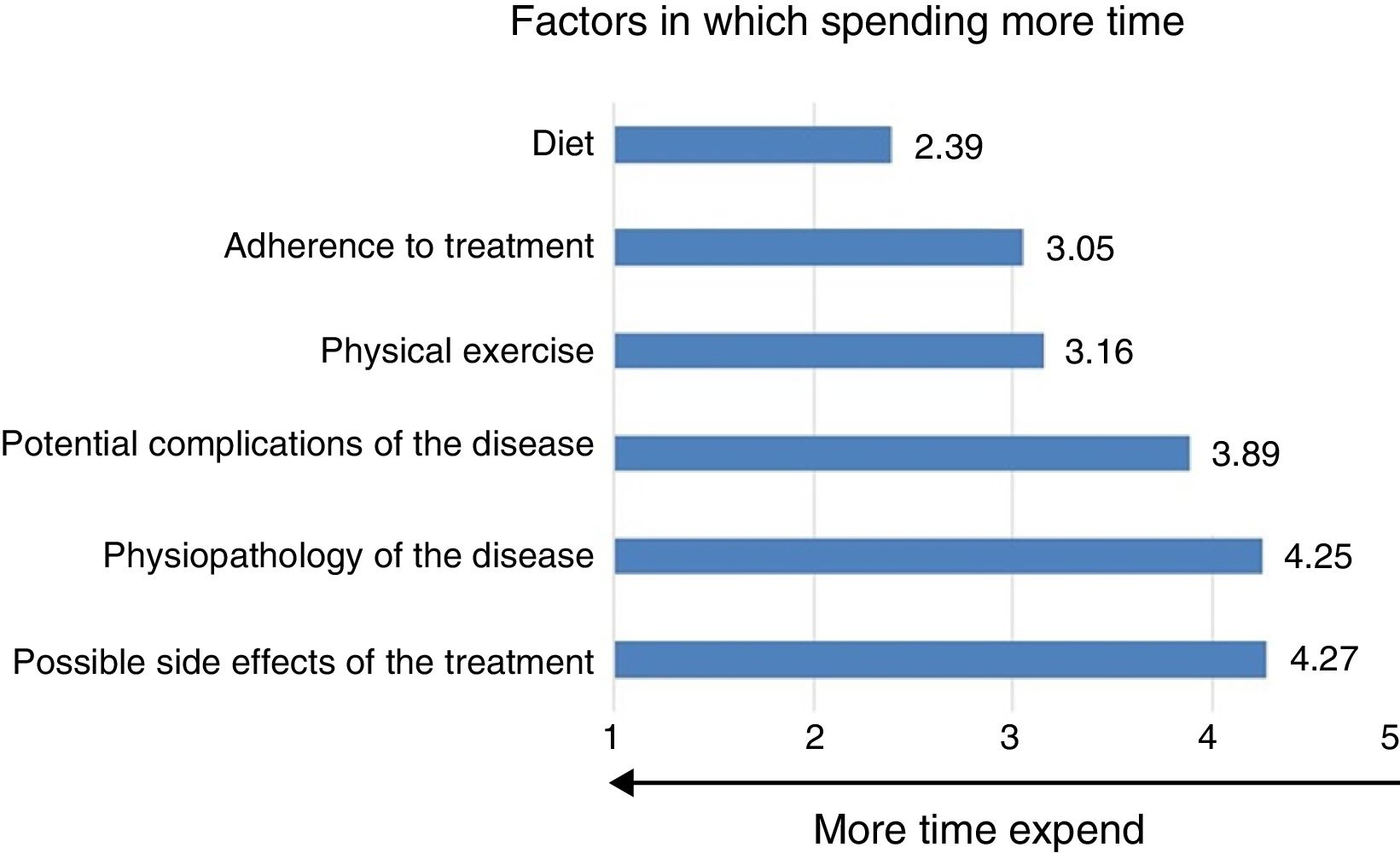

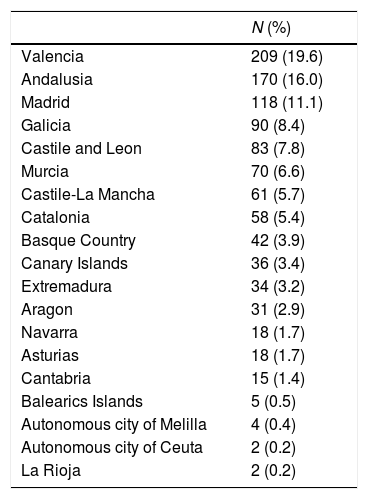

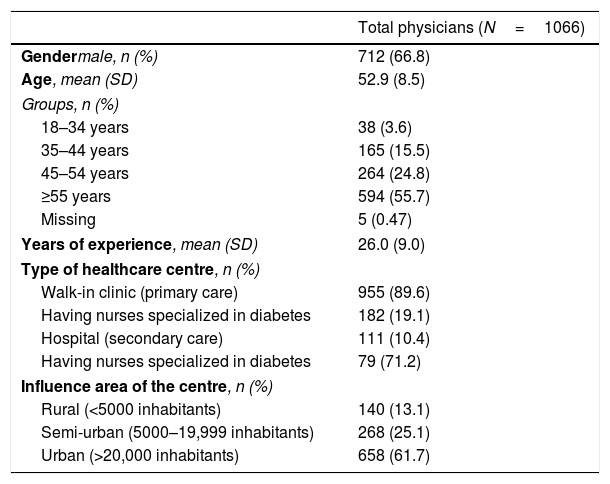

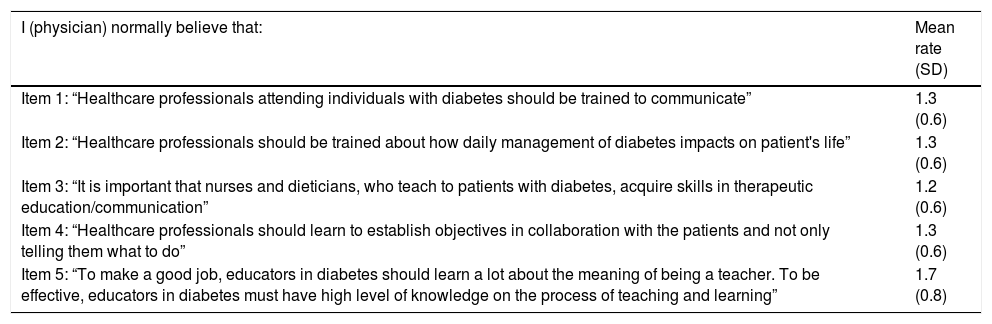

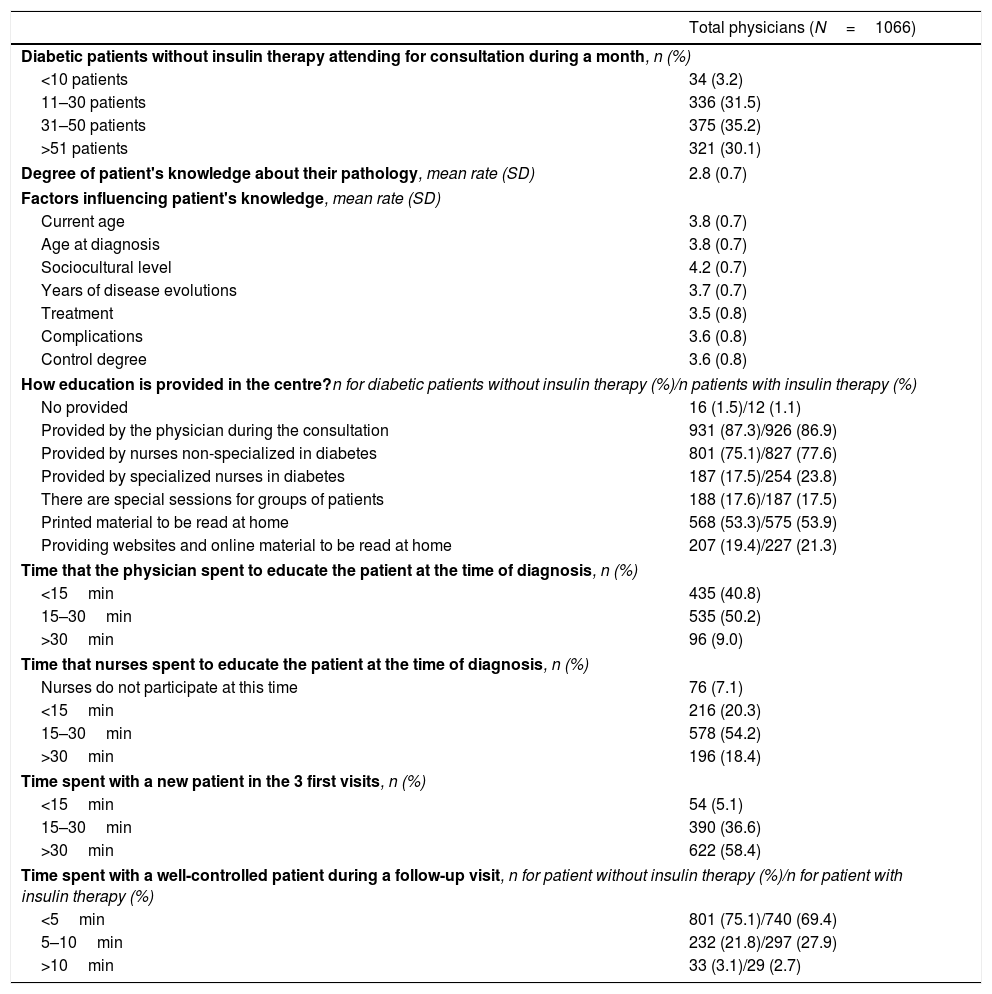

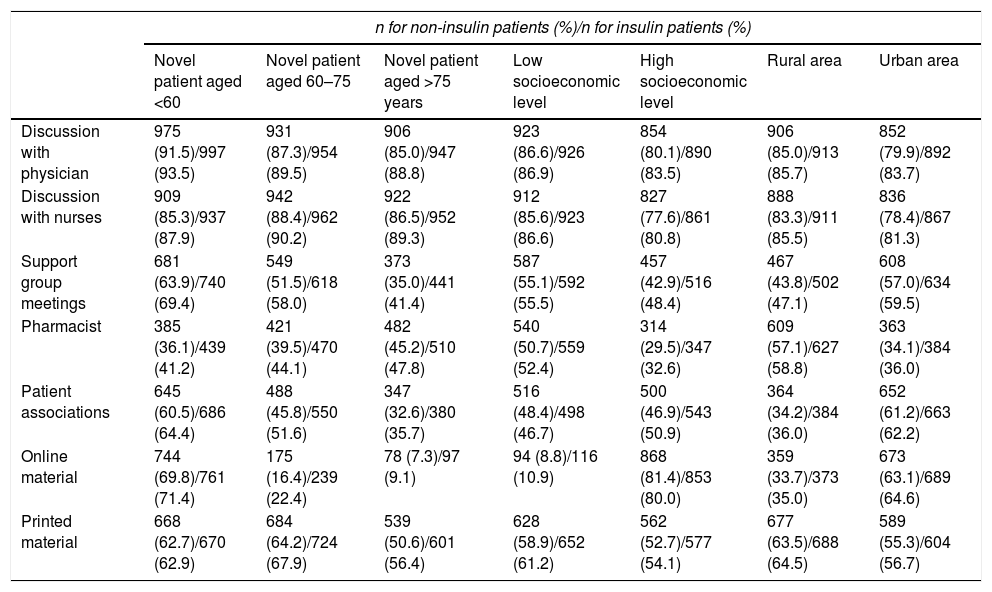

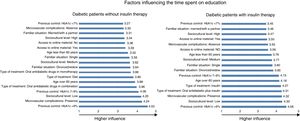

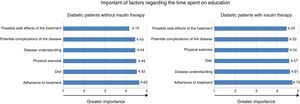

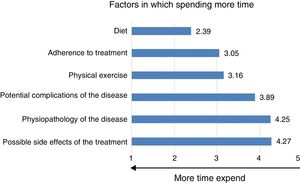

ResultsA total of 1066 physicians were included in the study. The location of the physicians in each autonomous community from Spain is shown in Table 1. Physicians were mainly male (66.8% of total), with a mean age of 52.9 years (SD 8.5), and 26 years (SD 9.0) of experience in healthcare. Demographic characteristics of physicians and healthcare centers are shown in Table 2. Physicians were mainly working in a walk-in clinic (primary care, 89.6% of total), and from an urban area (61.7%). Healthcare centers showed differences in the number of nurses specialized in diabetes (19.1% in walk-in clinic versus 71.2% in hospital). The attitude questionnaire and rates are shown in Table 3. All items were rated between 1 (totally agree) and 2 (agree). The greatest consensus was achieved by the item number 3: “It is important that nurses and dieticians, who teach to patients with diabetes, acquire skills in therapeutic education/communication”. No differences in rating were found related to primary or secondary care, or age. Physician perceptions about the education provided to patients are shown in Table 4. A total of 65% of physicians indicated that more than 30% of patients with diabetes without insulin therapy are attending consultation per month. No differences were found regarding type of care and age group. Physicians rated the degree of patient's knowledge about their pathology 2.8 on a 5.0 points scale. The most influential factor on patient's knowledge was sociocultural level. The education to patients with diabetes without insulin therapy was mainly provided by the physician during the consultation (87.3% of total; showing differences between primary care and secondary care, 89% versus 73%; respectively, P<0.001) and non-specialized nurses (75.1% of total; also showing differences between type of care, 81.2% versus 23.4%, respectively; P<0.001). The differences between primary and secondary care were related to the way education was provided (a) by nurses specialized in diabetes (13.9% versus 48.7%, respectively; P<0.001) and (b) through printed material to be read at home (54.9% versus 39.6%, respectively; P=0.003). Education was not provided by 1.5% of physicians whilst 53.3% of them indicated that it was provided via printed material to be read at home. The results were similar whether or not the patients were on insulin therapy. 50.2% of physicians indicated that they spent between 15 and 30min to educate patients at the time of diagnosis. A total of 75.1% reported to spend less than 5min in a follow-up visit of a well-controlled, patient with diabetes not treated with insulin. Physicians younger than 35 years provided significantly less time to well-controlled, patients with diabetes treated with insulin than older ones (P=0.04). Sociodemographic and clinical factors of patients influencing the time spent on education is shown in Fig. 1. Previous control with HbA1c>9% was the factor associated with spending more time in education in patients with diabetes not on insulin (mean rate 4.5, SD 0.6), or on insulin therapy (mean rate 4.6, SD 0.7). The following most influencing factor was the presence of microvascular complications (mean rate 4.2, SD 0.8), low sociocultural level (mean rate 4.2; SD 0.9), and previous control with HbA1c 7–9% (mean rate 4.1; SD 0.7), in patients without insulin therapy, and low sociocultural level (mean rate 4.3; SD 0.8), and presence of microvascular complications (mean rate 4.3, SD 0.8) in patients with diabetes on insulin therapy. Significant differences (P<0.05) were found depending on the type of care and age groups. Physicians from primary healthcare centers gave higher rates than secondary centers the following factors: age over 60, married/living with a partner, divorced/widow, microvascular complications, type of treatment, previous control with HbA1c 7–9% and >9%. Young physicians gave higher rates for the factors: age over 60, low sociocultural level, and the type of treatment (oral antidiabetic drugs in monotherapy). Physician perceptions of the importance of factors regarding the time spent on education are shown in Fig. 2. Adherence to treatment was the most important factor for spending time on education in both patients with diabetes without (mean rate 4.6, SD 0.6), or with insulin therapy (mean rate 4.7, SD 0.5). The following most important factors were diet (mean rate 4.5, SD 0.6), and physical exercise (mean rate 4.5, SD 0.7) in patients not on insulin therapy, and disease understanding (mean rate 4.6, SD 0.6), and diet (mean rate 4.6, SD 0.6), in patients with diabetes on insulin therapy. The factors that physicians have spent more time for education were: recommendations on diet (mean rate 2.4, SD 1.6), adherence to treatment (mean rate 3.1, SD 1.5), and recommendations on physical exercise (mean rate 3.2, SD 1.2; Fig. 3). Physician perceptions about the most adequate way of educating according to the patients’ demographic characteristics are shown in Table 5. Physicians indicated that discussions with physician and nurses are the main instruments of education for patients, regardless age, socioeconomic level, and area.

Location of the physicians in each autonomous community from Spain.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Valencia | 209 (19.6) |

| Andalusia | 170 (16.0) |

| Madrid | 118 (11.1) |

| Galicia | 90 (8.4) |

| Castile and Leon | 83 (7.8) |

| Murcia | 70 (6.6) |

| Castile-La Mancha | 61 (5.7) |

| Catalonia | 58 (5.4) |

| Basque Country | 42 (3.9) |

| Canary Islands | 36 (3.4) |

| Extremadura | 34 (3.2) |

| Aragon | 31 (2.9) |

| Navarra | 18 (1.7) |

| Asturias | 18 (1.7) |

| Cantabria | 15 (1.4) |

| Balearics Islands | 5 (0.5) |

| Autonomous city of Melilla | 4 (0.4) |

| Autonomous city of Ceuta | 2 (0.2) |

| La Rioja | 2 (0.2) |

Demographic characteristics of physicians and healthcare centers.

| Total physicians (N=1066) | |

|---|---|

| Gendermale, n (%) | 712 (66.8) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 52.9 (8.5) |

| Groups, n (%) | |

| 18–34 years | 38 (3.6) |

| 35–44 years | 165 (15.5) |

| 45–54 years | 264 (24.8) |

| ≥55 years | 594 (55.7) |

| Missing | 5 (0.47) |

| Years of experience, mean (SD) | 26.0 (9.0) |

| Type of healthcare centre, n (%) | |

| Walk-in clinic (primary care) | 955 (89.6) |

| Having nurses specialized in diabetes | 182 (19.1) |

| Hospital (secondary care) | 111 (10.4) |

| Having nurses specialized in diabetes | 79 (71.2) |

| Influence area of the centre, n (%) | |

| Rural (<5000 inhabitants) | 140 (13.1) |

| Semi-urban (5000–19,999 inhabitants) | 268 (25.1) |

| Urban (>20,000 inhabitants) | 658 (61.7) |

Attitude questionnaire and rates.a

| I (physician) normally believe that: | Mean rate (SD) |

|---|---|

| Item 1: “Healthcare professionals attending individuals with diabetes should be trained to communicate” | 1.3 (0.6) |

| Item 2: “Healthcare professionals should be trained about how daily management of diabetes impacts on patient's life” | 1.3 (0.6) |

| Item 3: “It is important that nurses and dieticians, who teach to patients with diabetes, acquire skills in therapeutic education/communication” | 1.2 (0.6) |

| Item 4: “Healthcare professionals should learn to establish objectives in collaboration with the patients and not only telling them what to do” | 1.3 (0.6) |

| Item 5: “To make a good job, educators in diabetes should learn a lot about the meaning of being a teacher. To be effective, educators in diabetes must have high level of knowledge on the process of teaching and learning” | 1.7 (0.8) |

Physician perceptions about the education provided to patients.

| Total physicians (N=1066) | |

|---|---|

| Diabetic patients without insulin therapy attending for consultation during a month, n (%) | |

| <10 patients | 34 (3.2) |

| 11–30 patients | 336 (31.5) |

| 31–50 patients | 375 (35.2) |

| >51 patients | 321 (30.1) |

| Degree of patient's knowledge about their pathology, mean rate (SD) | 2.8 (0.7) |

| Factors influencing patient's knowledge, mean rate (SD) | |

| Current age | 3.8 (0.7) |

| Age at diagnosis | 3.8 (0.7) |

| Sociocultural level | 4.2 (0.7) |

| Years of disease evolutions | 3.7 (0.7) |

| Treatment | 3.5 (0.8) |

| Complications | 3.6 (0.8) |

| Control degree | 3.6 (0.8) |

| How education is provided in the centre?n for diabetic patients without insulin therapy (%)/n patients with insulin therapy (%) | |

| No provided | 16 (1.5)/12 (1.1) |

| Provided by the physician during the consultation | 931 (87.3)/926 (86.9) |

| Provided by nurses non-specialized in diabetes | 801 (75.1)/827 (77.6) |

| Provided by specialized nurses in diabetes | 187 (17.5)/254 (23.8) |

| There are special sessions for groups of patients | 188 (17.6)/187 (17.5) |

| Printed material to be read at home | 568 (53.3)/575 (53.9) |

| Providing websites and online material to be read at home | 207 (19.4)/227 (21.3) |

| Time that the physician spent to educate the patient at the time of diagnosis, n (%) | |

| <15min | 435 (40.8) |

| 15–30min | 535 (50.2) |

| >30min | 96 (9.0) |

| Time that nurses spent to educate the patient at the time of diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Nurses do not participate at this time | 76 (7.1) |

| <15min | 216 (20.3) |

| 15–30min | 578 (54.2) |

| >30min | 196 (18.4) |

| Time spent with a new patient in the 3 first visits, n (%) | |

| <15min | 54 (5.1) |

| 15–30min | 390 (36.6) |

| >30min | 622 (58.4) |

| Time spent with a well-controlled patient during a follow-up visit, n for patient without insulin therapy (%)/n for patient with insulin therapy (%) | |

| <5min | 801 (75.1)/740 (69.4) |

| 5–10min | 232 (21.8)/297 (27.9) |

| >10min | 33 (3.1)/29 (2.7) |

Physician perceptions about the most adequate way of education regarding demographic characteristics of patients.

| n for non-insulin patients (%)/n for insulin patients (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novel patient aged <60 | Novel patient aged 60–75 | Novel patient aged >75 years | Low socioeconomic level | High socioeconomic level | Rural area | Urban area | |

| Discussion with physician | 975 (91.5)/997 (93.5) | 931 (87.3)/954 (89.5) | 906 (85.0)/947 (88.8) | 923 (86.6)/926 (86.9) | 854 (80.1)/890 (83.5) | 906 (85.0)/913 (85.7) | 852 (79.9)/892 (83.7) |

| Discussion with nurses | 909 (85.3)/937 (87.9) | 942 (88.4)/962 (90.2) | 922 (86.5)/952 (89.3) | 912 (85.6)/923 (86.6) | 827 (77.6)/861 (80.8) | 888 (83.3)/911 (85.5) | 836 (78.4)/867 (81.3) |

| Support group meetings | 681 (63.9)/740 (69.4) | 549 (51.5)/618 (58.0) | 373 (35.0)/441 (41.4) | 587 (55.1)/592 (55.5) | 457 (42.9)/516 (48.4) | 467 (43.8)/502 (47.1) | 608 (57.0)/634 (59.5) |

| Pharmacist | 385 (36.1)/439 (41.2) | 421 (39.5)/470 (44.1) | 482 (45.2)/510 (47.8) | 540 (50.7)/559 (52.4) | 314 (29.5)/347 (32.6) | 609 (57.1)/627 (58.8) | 363 (34.1)/384 (36.0) |

| Patient associations | 645 (60.5)/686 (64.4) | 488 (45.8)/550 (51.6) | 347 (32.6)/380 (35.7) | 516 (48.4)/498 (46.7) | 500 (46.9)/543 (50.9) | 364 (34.2)/384 (36.0) | 652 (61.2)/663 (62.2) |

| Online material | 744 (69.8)/761 (71.4) | 175 (16.4)/239 (22.4) | 78 (7.3)/97 (9.1) | 94 (8.8)/116 (10.9) | 868 (81.4)/853 (80.0) | 359 (33.7)/373 (35.0) | 673 (63.1)/689 (64.6) |

| Printed material | 668 (62.7)/670 (62.9) | 684 (64.2)/724 (67.9) | 539 (50.6)/601 (56.4) | 628 (58.9)/652 (61.2) | 562 (52.7)/577 (54.1) | 677 (63.5)/688 (64.5) | 589 (55.3)/604 (56.7) |

For an effective management of DM, patients need to be involved in their care, make decisions about their lifestyle (physical exercise, diet) and medical self-care (medication adherence and blood glucose self-monitoring).18,19 The education of the patient is key factor for improving the therapeutic compliance and meeting physician's recommendations on diet and exercise. To date, there is limited information about the quality of the education provided to patients and the tools used. On our knowledge this is the first study specifically designed to evaluate the education provided to patients with DM from Spain. The recent IMAGINE study, involving 302 family physicians, internists and endocrinologists and aimed to analyze the care and comorbidity of patients with DM in the Spanish National Health System, indicated that diabetes education is shared between both physicians (mainly for anti-tobacco counseling and glycemic self-analysis reviews) and nurses (for insulin techniques, physical activity, diet planning and foot examinations).20 The mean time spent when providing dietetic information was <10min, and <5min when recommending aerobic exercise. In concordance with literature,13 our data indicate that physicians and nurses are the main responsible of the education for patients. Moreover, they are responsible regardless the age, socioeconomic level, and rural or urban origin of the patient. Our physicians also indicated that the time spent with a well-controlled patient during a follow-up visit was less than 5min; however, physicians (50.2%) and nurses (54.2%) spent at the time of diagnosis between 15 and 30min in education, mainly through discussion. There are studies that have demonstrated the positive correlation between diabetes knowledge and glycemic control.21,22 In our study, physicians spent more time when in the previous control, HbA1c was >9 in both patients with or without insulin therapy. The presence of microvascular complications and a low sociocultural level were also the most important factors for spending more time in education. Moreover, adherence was the factor that physicians considered with highest importance for educating. Diabetes knowledge has also been observed to influence medication adherence.23 In a cross-sectional study involving 540 adult patients with DM, the authors demonstrated that knowledge and better adherence were significantly associated. Indeed, they also showed that higher knowledge, adherence and receiving monotherapy were significant predictors of good glycemic control. In our study, the diet was also an important factor for spending more time in education. One limitation of the study is that the quality of the education that patients receive has been evaluated from the physician's perspective. Although conclusions from this study would have been stronger if patient's perspective were also collected, in our opinion the results from the present study are interesting because illustrating what happens in daily clinical practice. Another limitation was that the number of participating physicians in each autonomous community was not homogeneous, due to the limited availability of physicians willing to participate in the study and fulfilling the inclusion criteria in each autonomous community. Although a similar number could reduce potential bias in the opinion of the physicians associated with their geographic location; in our opinion, the representation of physicians from all Spanish autonomous communities allows extrapolating, cautiously, the conclusions to a national level.

Practice implicationsKnowing what patients know and understand about their disease and treatments is critical for an effective management of DM. According to the information collected from this survey, the time spent on education during each visit should be carefully taken into account by the physician. Physicians and nurses share responsibilities with respect to patient's education. Indeed, there is a consensus among them that 15 and 30min at the time of the diagnosis is an appropriate time for education. However, during follow-up visits, the time on education should be, at least, more than 5min.

ConclusionThis is the first study specifically designed to evaluate the education provided to patients with T2DM from Spain, and it demonstrates that the time spent and the individualization of the education are important factors associated with long-term control of the disease and thus with effectiveness of the management.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors would like to thank to Ana López Fernández (Forma2 study assistant) and Dr. Mariona Lería (Pharmacovigilance Manager, Mylan). Authors would also like to thank Pablo Vivanco (PhD, Meisys) for assisting in the preparation of the manuscript. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.