Dias-Logan syndrome, or intellectual developmental disorder with persistence of foetal haemoglobin (HbF), is caused by pathogenic variants of the BCL11A gene,1 and follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. To date, only 29 cases have been reported in the literature, with the great majority (28/29) being attributed to de novo mutations.2–4 The disease is characterised by psychomotor retardation and intellectual disability of variable severity; language and behavioural disorders; various types of epilepsy (tonic, myoclonic, atonic, and absence seizures; epileptic spasms); hypotonia; microcephaly; joint hypermobility; strabismus; variable craniofacial anomalies; and elevated HbF levels. Cases have also been described of non-specific malformations of the central nervous system (hypoplasia of the corpus callosum and cerebellar vermis, white matter defects, etc) and epileptic encephalopathy.5

The BCL11A gene encodes a regulatory C2H2 type zinc-finger protein, which plays an essential role in multiple tissues during human development, and particularly in γ- to β-globin switching during the transition from fetal to adult erythropoeisis. The disease is caused by loss-of-function variants of the gene; to date, nonsense and frameshift mutations, intragenic or complete deletions, and some missense variants have been described.6

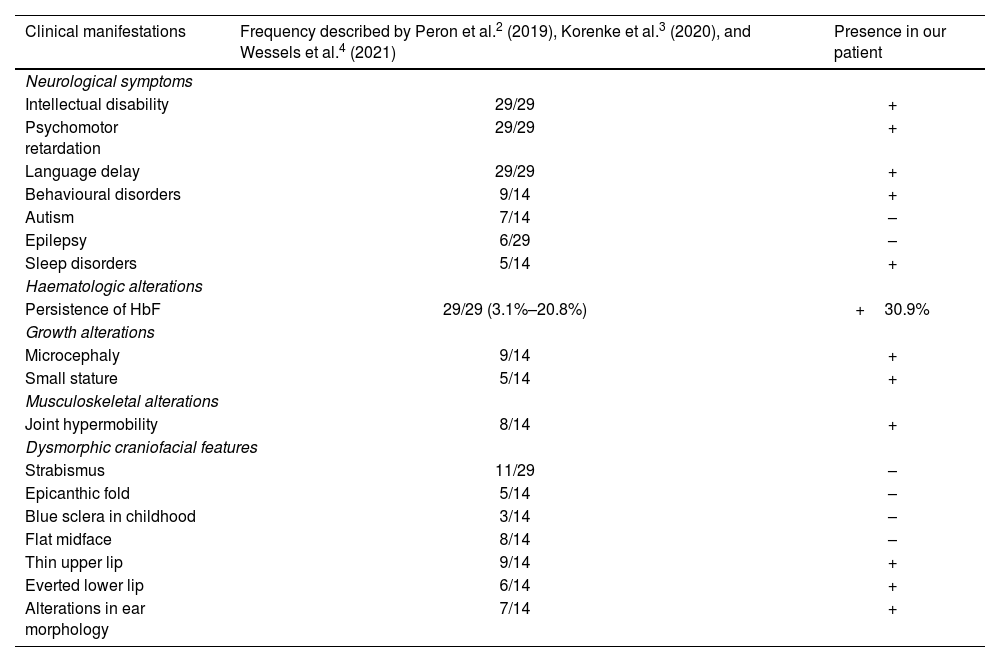

We describe the case of an 11-year-old boy who was referred by the paediatric neurology department to the genetics consultation due to mild intellectual disability, microcephaly, and dysmorphic features. He was the third child of healthy, non-consanguineous parents from Colombia. He had no relevant family history, with the exception of a 19-year-old brother who had academic difficulties, diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The patient was born after a spontaneous, uneventful pregnancy. Exposure to alcohol and other drugs was ruled out. He was delivered vaginally at full term, with a birth weight of 3270 g, with no need for resuscitation; the neonatal period was normal. The blood spot and otoacoustic emission tests yielded normal results. Regarding development, he presented no feeding difficulties, but has always presented poor growth, with height, weight, and head circumference in low percentiles. He presented global developmental delay, walking at 20 months of age and uttering his first referential words at approximately 2 years. He attended a normal school, receiving educational support, and had repeated a year. He is currently under follow-up by the mental health and paediatric neurology departments due to mild/borderline intellectual disability (IQ of 79), language disorder, and ADHD. He presented a generalised tonic-clonic seizure at the age of 8 years, after starting treatment with methylphenidate, subsequently remaining seizure-free. The patient’s family reported irregular sleep with multiple awakenings; sleep improved with administration of melatonin. Table 1 compares the patient’s clinical signs with those described in the literature.

Clinical characteristics of our patient and of the cases reported in the literature.

| Clinical manifestations | Frequency described by Peron et al.2 (2019), Korenke et al.3 (2020), and Wessels et al.4 (2021) | Presence in our patient |

|---|---|---|

| Neurological symptoms | ||

| Intellectual disability | 29/29 | + |

| Psychomotor retardation | 29/29 | + |

| Language delay | 29/29 | + |

| Behavioural disorders | 9/14 | + |

| Autism | 7/14 | – |

| Epilepsy | 6/29 | – |

| Sleep disorders | 5/14 | + |

| Haematologic alterations | ||

| Persistence of HbF | 29/29 (3.1%–20.8%) | +30.9% |

| Growth alterations | ||

| Microcephaly | 9/14 | + |

| Small stature | 5/14 | + |

| Musculoskeletal alterations | ||

| Joint hypermobility | 8/14 | + |

| Dysmorphic craniofacial features | ||

| Strabismus | 11/29 | – |

| Epicanthic fold | 5/14 | – |

| Blue sclera in childhood | 3/14 | – |

| Flat midface | 8/14 | – |

| Thin upper lip | 9/14 | + |

| Everted lower lip | 6/14 | + |

| Alterations in ear morphology | 7/14 | + |

Physical examination performed when the patient was 11 years old revealed weight of 25.2 kg (percentile 10), height of 130 cm (percentile 5), and head circumference of 50 cm (below percentile 1: –2.75 standard deviations). He also presented dysmorphic facial features (Fig. 1).

Complementary testing during follow-up by the paediatric neurology department revealed the following results: normal brain MRI and EEG findings; normal CGH array results; negative fragile X syndrome molecular genetic test results; blood and urine metabolic panel results revealing normal profiles for sialotransferrin, amino acids, organic acids, creatine/creatinine, SAICAr, sulfites (Sulfitest), acylcarnitines, lactate/pyruvate, and glycosaminoglycans. After assessment by the genetics department, we requested clinical exome sequencing, identifying four variants of uncertain significance in the CHD8, KMT2C, and ANKRD11 genes, associated with syndromes with partially overlapping phenotypes (susceptibility to autism and intellectual disability with macrocephaly, Kleefstra syndrome 2, and KBG syndrome, respectively), and a probably pathogenic BCL11A variant, associated with Dias-Logan syndrome. We requested studies of the ANKRD11 and BCL11A genes in the patient’s parents, as his clinical phenotype closely resembled those associated with KBG syndrome and Dias-Logan syndrome. The results conclusively established that heterozygous presence of a frameshift mutation (c.1076_1100del) in the BCL11A gene was due to a de novo mutation. Persistence of HbF was confirmed in the haemoglobin electrophoresis test: HbA, 67%; HbA2, 1.5%; HbF, 30.9%. We subsequently requested a study to detect the variant in the patient’s brother due to the possibility of germline mosaicism in the parents, obtaining negative results.

This case demonstrates the great value of clinical exome sequencing to identify cases of non-specific neurodevelopmental disorder with very low prevalence.

We report a novel variant of the BCL11A gene, expanding the genotype of Dias-Logan syndrome.

Our patient’s clinical signs were very similar to those described in the literature: global developmental delay with significant language involvement, intellectual disability, and persistence of HbF are described in nearly all reported cases.

Although patients with Dias-Logan syndrome do not present a distinctive facial phenotype, haemoglobin electrophoresis should be considered in patients with intellectual disability, microcephaly, and epilepsy, as the test may enable earlier diagnosis, which has consequences both for the patient and for their family.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that they have followed their center's protocols on the publication of patient data and have obtained the corresponding permissions.