Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection may cause gastric ulcers or extra-gastroduodenal disorders, including iron deficiency anemia. This study aimed to determine the relationship between H. pylori infection and iron deficiency anemia (IDA).

MethodsA case–control study was conducted on participants aged ≥18 with an indication for gastric endoscopy. The cases were identified by positive rapid urease tests with biopsy specimens obtained during gastric endoscopy. The controls were negative rapid urease tests. Blood samples from the participants were taken for hematological indices and other iron-related parameters.

ResultsA total of 230 participants including 115 cases and 115 controls were eligible for the study. H. pylori positive group had significantly a lower mean value of hemoglobin (P<.001), mean corpuscular volume (MCV) (P<.001), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) (P<.001), serum iron (P<.001), and transferrin saturation (TSAT) (p<.001) compared to the counterparts; meanwhile, ferritin levels showed an insignificant difference between 2 groups (P>.05). The rate of iron deficiency anemia was significantly higher in the cases than in the controls (χ2=16.05; P<.001). A significant association was found between H. pylori infection and anemia, iron deficiency with age and sex-adjusted ORs of 7.59 (95% CI=3.83–15.05, P<.001) and 2.12 (95% CI=1.05–4.25, P=.035), respectively.

ConclusionsOur study found a significant association between H. pylori infection and anemia, and iron deficiency. The relationship between H. pylori infection and iron deficiency anemia has not been conclusively established. H. pylori-infected individuals should be screened for IDA.

La infección por Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) puede causar úlceras gástricas o trastornos extra-gastroduodenales, incluida la anemia por deficiencia de hierro. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo determinar la relación entre la infección por H. pylori y la anemia por deficiencia de hierro (IDA).

MétodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio de casos y controles en participantes mayores de 18 años con indicación de endoscopia gástrica. Los casos fueron identificados por pruebas rápidas de ureasa positivas con muestras de biopsia obtenidas durante la endoscopia gástrica. Los controles tenían pruebas rápidas de ureasa negativas. Se tomaron muestras de sangre de los participantes para obtener índices hematológicos y otros parámetros relacionados con el hierro.

ResultadosUn total de 230 participantes, incluidos 115 casos y 115 controles, fueron elegibles para el estudio. El grupo positivo para H. pylori tuvo significativamente un valor medio más bajo de hemoglobina (p<0.001), volumen corpuscular medio (MCV) (p<0.001), concentración de hemoglobina corpuscular media (MCHC) (p<0.001), hierro sérico (p<0.001) y saturación de transferrina (TSAT) (p<0.001) en comparación con los contrapartes; mientras tanto, los niveles de ferritina mostraron una diferencia no significativa entre los dos grupos (p>0.05). La tasa de anemia por deficiencia de hierro fue significativamente mayor en los casos que en los controles (χ2=16.05; p<0.001). Se encontró una asociación significativa entre la infección por H. pylori y la anemia, con OR ajustadas por edad y sexo de 7.59 (IC del 95% = 3.83-15.05, p<0.001) y 2.12 (IC del 95% = 1.05-4.25, p=0.035), respectivamente.

ConclusiónNuestro estudio encontró una asociación significativa entre la infección por H. pylori y la anemia, así como la deficiencia de hierro. La relación entre la infección por H. pylori y la anemia por deficiencia de hierro no se ha establecido de manera concluyente. Las personas infectadas con H. pylori deben ser evaluadas para detectar la IDA.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is one of the most common and persistent bacterial infections worldwide, with a wide variation of prevalence from 22% to 87%, especially in developing countries.1,2 The manifestations of H. pylori infection vary from asymptomatic to symptomatic. Disorders commonly caused by H. pylori infection are gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, gastric ulcers, and gastric cancer.3 In addition to gastroduodenal diseases, numerous studies have shown that H. pylori infection can cause disorders outside the gastrointestinal tract.4 Iron deficiency anemia is one of the most concerning disorders among extra-gastroduodenal disorders.4,5

Increasing evidence has reported an association between H. pylori infection and iron deficiency anemia (IDA).6–12 Many studies also found that eradication of H. pylori leads to improvement in iron deficiency anemia.6,12–14 This evidence indirectly supports the association between H. pylori infection and iron deficiency anemia. Given the association between H. pylori infection and iron deficiency anemia, several studies and guidelines suggest that H. pylori infection should be screened for and treated if detected in adults with unexplained iron deficiency anemia.6,14,15 The mechanism of H. pylori infection producing iron deficiency anemia has still been hypothesized. Blood loss due to bleeding from peptic ulcers, and hemorrhagic gastritis caused by H. pylori infection; inadequate iron absorption due to decreased levels of ascorbic acid and stomach acidity resulting from H. pylori chronic gastritis; and increased utilization of iron by H. pylori for their growth have been considered as mechanisms of iron deficiency anemia caused by H. pylori infection.4,5,16,17

However, some studies have reported that the association between H. pylori infection and iron deficiency anemia was not significant.18–20 Tseng et al even found no association between iron deficiency anemia and H. pylori infection and no improvement in iron deficiency anemia after H. pylori treatment.21 These findings suggest that the association between H. pylori infection and iron deficiency anemia is still conflicting due to differences in sampling method, the iron deficiency anemia criteria, and the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the study population among the studies.22 Iron deficiency anemia in individuals with H. pylori infection has not received much attention in Vietnam, although the prevalence of H. pylori infection in Vietnam is quite high at 70.3%1 and the proportion of anemia associated with iron deficiency among adults in Vietnam is high at 35.2%.23 This study aimed to determine the association between H. pylori infection and iron deficiency anemia to propose an approach to individuals infected with H. pylori.

Material and methodsStudy design and settingA case–control study was conducted on participants who came for medical examinations and health check-ups at Branch 2 of the University Medical Center Ho Chi Minh City from December 2020 to June 2021. The University Medical Center is a hospital affiliated with the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City. It is one of the largest hospitals in Vietnam, located in Ho Chi Minh City; an average of 1000 outpatient visits, 70 upper gastrointestinal endoscopy cases, and 4000 tests per day are served at Branch 2.

Study participants and samplingParticipants over 18 years old who were examined, evaluated, and indicated for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy were included in the study. All participants signed written informed consent forms before participating in the study. Participants were asked to fast for a minimum of 4 h before the endoscopy. The case group included those whose biopsy samples taken by endoscopy were positive with rapid urease tests. The control group included those whose biopsy samples were negative with the rapid urease tests. The ratio of the case: control was 1:1 with matching sex and age. A consecutive sampling was performed to collect data. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the participants who took antibiotics for H. pylori in the 4 weeks before endoscopy or took proton pump inhibitors in the 2 weeks before endoscopy; (2) the participants who were taking non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs; (3) those who had diseases that cause anemia or affect hematopoiesis such as malignancies, hematological diseases, and chronic diseases; (4) those who were pregnant, menstruating, and breastfeeding women; (5) those who showed signs of active bleeding (melena, hematemesis, hematuria, epistaxis).

Laboratory measurementsBlood collecting was performed before the endoscopy. Each participant had 5 ml of venous blood drawn in the morning after fasting for at least 8 h. 2.5 ml of blood was collected into an EDTA tube for analysis of hematological parameters including hemoglobin (Hb) level, hematocrit (Hct), red blood cell (RBC) count, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), and red cell distribution width (RDW). Blood samples were analyzed using the Alnity analyzer (Abbott Diagnostics, Ireland). Reference range values for MCV, MCH, MCHC, and RDW are 80–100 fL, 28–35 pg, 32–36 g/dL, and 11%–15%, respectively.16 The remaining 2.5 ml of blood was collected into a serum tube for measurement of iron-related parameters including serum iron, ferritin, transferrin, total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), and transferrin saturation (TSAT). The iron, ferritin, and transferrin indices were measured with an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Beckman Coulter AU680 Chemistry Analyzer, USA). The reference range values for serum iron, ferritin, and transferrin were 50–160 μg/dL, 30–400 ng/mL, and 2.0–3.6 g/L, respectively.16 Total iron binding capacity (TIBC) was calculated by the formula: TIBC (μg/dL)=Transferrin (mg/dL)×1.25.24 The reference range value for TIBC was 255–450 μg/dL. Transferrin saturation (TSAT - Transferrin saturation) was calculated by the formula: TSAT=(Serum iron/TIBC)×100%. The reference range value for TSAT was 20%–50%.16

Determination of H. pylori infectionBiopsy specimens taken from performing endoscopy were analyzed for H. pylori determination using a rapid urease test (CLO test, Kimberley-Clark, USA). The specimens were processed according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the results were read within 30 min. A change of gel color from yellow to magenta (purple-red) was considered a positive for H. pylori.

Definition of anemia, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemiaAnemia was defined according to the criteria established by the World Health Organization, with hemoglobin levels below 13 g/dL in men and 12 g/dL in women.25 Iron deficiency was defined as serum ferritin <30 ng/mL. Iron deficiency anemia was defined as anemia associated with: (1) Serum ferritin level <30 ng/mL; (2) TSAT <20 %; (3) MCH <28 pg.26,27 Microcytic hypochromic anemia was defined as anemia with MCV <80 fL and MCH <28 pg; normocytic normochromic anemia was defined as anemia with 80 fL≤MCV≤100 fL and 28 pg≤MCH≤35 pg; normocytic hypochromic anemia was defined as anemia with MCV <80 fL and 28 pg≤MCH≤35 pg.

Ethical considerationAll participants were voluntary to participate in the study and signed written informed consent before being recruited in the study. All participants can withdraw from the study without any consequences and at any time. The data forms were coded and anonymous. All participants’ data were confidential. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City under Decision No. 838/HĐĐĐ-ĐHYD issued on November 9, 2020.

Statistical analysesStatistical analyses were performed using STATA version 15.1. Baseline characteristics for categorical variables were presented as frequencies and proportions, while means and standard deviations, or medians and interquartile ranges, were used for continuous variables. Student's t-test was employed for normally distributed continuous variables, and the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed continuous variables to compare differences between the two groups. The χ2 test was employed to compare differences for categorical data. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) with dependent variables including anemia, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia. The multivariate logistic regression models were adjusted for sex and age. A two-sided P-value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsBaseline characteristics of participantsThis study included 115 subjects in the H. pylori-positive group and 115 subjects in the H. pylori-negative group. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study population. The mean age of the study population was 44.5±12.3 years, males accounted for 44.4% of the total population. Two-thirds of the cohort lived in urban areas, most of the participants were employed (92.6%), and Kinh ethnicity accounted for 76.5% of the total. There were no significant differences in age, sex, occupational status, residency, and ethnicity between the cases and controls.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Variables | Overall | H. pylori (+) | H. pylori (–) | P values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=230 | n=115 | n=115 | ||

| Age (mean±SD) | 44.5±12.3 | 43.2±13.2 | 45.9±11.2 | .096b |

| Age groups (%) | ||||

| ≤30 | 30 (13.1) | 21 (18.3) | 9 (7.8) | .052a |

| 31–40 | 47 (20.5) | 21 (18.3) | 26 (22.6) | |

| 41–50 | 82 (35.6) | 41 (35.6) | 41 (35.6) | |

| 51–60 | 50 (21.7) | 19 (16.5) | 31 (27.0) | |

| >61 | 21 (9.1) | 13 (11.3) | 8 (7.0) | |

| Sex (%) | ||||

| Male | 102 (44.4) | 53 (46.1) | 49 (42.6) | .595a |

| Female | 128 (55.6) | 62 (53.9) | 66 (57.4) | |

| Occupation (%) | ||||

| Employed | 213 (92.6) | 107 (93.0) | 106 (92.3) | .801a |

| Unemployed | 17 (7.4) | 8 (7.0) | 9 (7.8) | |

| Residency (%) | ||||

| Urban | 152 (66.1) | 72 (62.6) | 80 (69.6) | .365a |

| Rural | 78 (33.9) | 43 (37.4) | 35 (40.4) | |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| Kinh | 176 (76.5) | 84 (73.0) | 92 (80.0) | .213a |

| Others | 54 (23.5) | 31 (27.0) | 23 (20.0) | |

Table 2 shows the hematological indices and iron-related parameters between the 2 groups. The mean serum iron of the H. pylori-positive group was 59.4±42.1 μg/dL which was significantly lower than that of the H. pylori-negative group (88.1±32.5 μg/dL) (P<.001) (Table 2, Fig. 1A). Similarly, the mean TSAT value was significantly lower in the H. pylori-positive group compared to the counterparts (18.6±13.8% vs. 25.9±9.7%; P<.001) (Table 2, Fig 1D). Otherwise, there was no significant difference in serum ferritin, transferrin, and TIBC levels between the 2 groups (P>.05) (Table 2, Fig. 1B). The mean hemoglobin (Hb) concentration of the H. pylori-positive group was significantly lower than that of the H. pylori-negative group (12.6±2.2 g/dL vs. 13.9±1.4 g/dL, P<.001) (Table 2, Fig. 1C). Other hematological parameters, such as Hct (39.0±6.5% vs. 42.2±4.0%, P<.001), MCV (81.0±10.6 fL vs. 88.5±6.0 fL, P<.001), MCH (27.3±4.0 pg vs. 29.1±2.1 pg, P<.001), and MCHC (32.6 [31.2–33.6] vs. 32.9 [32.3–33.6], P=.03) also had the same difference as Hb between the case group and control group. However, RDW values were significantly higher in the H. pylori-infected individuals compared to their counterparts (14.1±1.6% vs. 12.9±0.9%, P<.001). Mean RDW values in the H. pylori-infected group having microcytic hypochromic anemia were 14.6±0.9% (data not shown in Table 2). Mean RBC counts were not significantly different between the 2 groups (P=.278).

Comparison of hematological and iron-related indices according to Helicobacter pylori infection status.

| Variables | Overall | H. pylori (+) | H. pylori (–) | P values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=230 | n=115 | n=115 | ||

| Serum iron (μg/dL)a | 73.8±40.2 | 59.4±42.1 | 88.1±32.5 | <.001c |

| Serum transferrin (g/L)a | 2.5±0.5 | 2.4±0.6 | 2.4±0.4 | .865c |

| Serum ferritin (ng/mL)b | 122.7 [42.4–208.3] | 103.5 [30.4–389.5] | 133.1 [56.6–224.1] | .623d |

| Serum TIBC (μg/dL)a | 346.8±77.4 | 346.3±92.3 | 347.3±59.2 | .922c |

| TSAT (%)a | 22.3±12.4 | 18.6±13.8 | 25.9±9.7 | <.001c |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL)a | 13.2±2.0 | 12.6±2.2 | 13.9±1.4 | <.001c |

| RBC (×1012/L)a | 4.7±0.8 | 4.7±0.9 | 4.8±0.6 | .278c |

| Hct (%)a | 40.6±5.6 | 39.0±6.5 | 42.2±4.0 | <.001c |

| MCV (fL)a | 84.8±9.4 | 81.0±10.6 | 88.5±6.0 | <.001c |

| MCH (pg)a | 28.2±3.3 | 27.3±4.0 | 29.1±2.1 | <.001c |

| MCHC (g/dL)b | 32.8 [31.9–33.6] | 32.6 [31.2–33.6] | 32.9 [32.3–33.6] | .030d |

| RDW (%)a | 13.5±1.4 | 14.1±1.6 | 12.9±0.9 | <.001c |

TIBC: total iron binding capacity; TSAT: transferrin saturation; RBC: red blood cell; Hct: hematocrit; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC: mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration. RDW: red cell distribution width.

The rate of anemia, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia in the H. pylori-positive group was significantly higher than that in the H. pylori-negative group (χ2=38.57; χ2=4.83; and χ2=16.05; P<.001, respectively) (Table 3). The rate of microcytic hypochromic anemia accounted for 52.5% of total cases of anemia in H. pylori-infected individuals (31/59) (Table 3). The rate of microcytic hypochromic anemia is significantly higher in the case group than in the control group (χ2=35.83, P<.001). In contrast, there was no significant difference in other types of anemia between the cases and the controls (P>.05) (Table 3).

Comparison of anemia, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia between the H. pylori-positive group and H. pylori-negative group.

| Variables | Overall | H. pylori (+) | H. pylori (–) | χ2 value | P values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=230 | n=115 | n=115 | |||

| Anemia | |||||

| Yes | 74 (32.2) | 59 (51.3) | 15 (13.0) | 38.57 (OR=7.02) | <.001a |

| No | 156 (67.8) | 56 (48.7) | 100 (87.0) | ||

| Microcytic hypochromic anemia | |||||

| Yes | 31 (13.5) | 31 (27.0) | 0 (0.0) | 35.83 | <.001b |

| No | 199 (86.5) | 84 (73.0) | 100 (100.0) | ||

| Normocytic normochromic anemia | |||||

| Yes | 25 (10.9) | 12 (10.4) | 13 (11.3) | 0.05 (OR=0.91) | .832a |

| No | 205 (89.1) | 103 (89.6) | 102 (88.7) | ||

| Normocytic hypochromic anemia | |||||

| Yes | 6 (2.6) | 4 (3.5) | 2 (1.7) | 0.68 (OR=2.04) | .683b |

| No | 224 (97.4) | 111 (96.5) | 113 (98.3) | ||

| Iron deficiency | |||||

| Yes | 43 (18.7) | 28 (24.4) | 15 (13.0) | 4.83 (OR=2.15) | .028a |

| No | 187 (81.3) | 87 (75.6) | 100 (87.0) | ||

| Iron deficiency anemia | |||||

| Yes | 15 (6.5) | 15 (13.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16.05 | <.001b |

| No | 215 (93.5) | 100 (87.0) | 115 (100.0) | ||

OR: odds ratio.

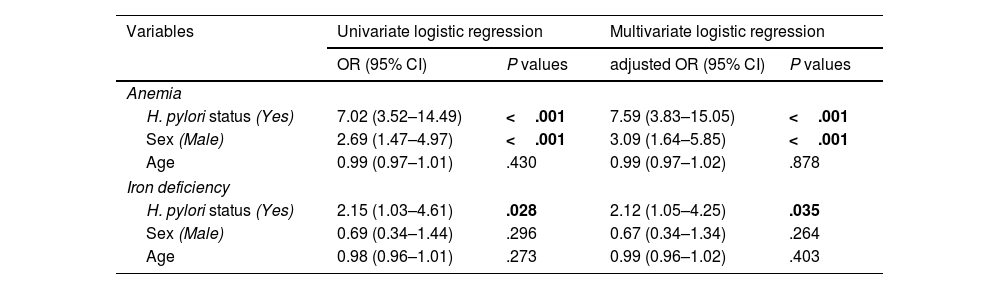

The association between H. pylori infection and anemia, and iron deficiency is shown in Table 4. In the univariate logistic regression analysis, anemia was found to be associated with H. pylori infection (OR=7.02; 95% CI=3.52–14.49) and male sex (OR=2.69; 95% CI=1.47–4.97). Iron deficiency was only associated with H. pylori infection (OR=2.15; 95% CI=1.03–4.61), but insignificantly related to age and male sex (P>.05). In the multivariate logistic regression analyses, a significant association was found between H. pylori infection and anemia, and iron deficiency with an age and sex-adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 7.59 (95% CI=3.83–15.05, P<.001) and 2.12 (95% CI=1.05–4.25, P=.035), respectively (Table 4).

Association between anemia, iron deficiency, and Helicobacter pylori infection in the study population using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis.

| Variables | Univariate logistic regression | Multivariate logistic regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P values | adjusted OR (95% CI) | P values | |

| Anemia | ||||

| H. pylori status (Yes) | 7.02 (3.52–14.49) | <.001 | 7.59 (3.83–15.05) | <.001 |

| Sex (Male) | 2.69 (1.47–4.97) | <.001 | 3.09 (1.64–5.85) | <.001 |

| Age | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | .430 | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | .878 |

| Iron deficiency | ||||

| H. pylori status (Yes) | 2.15 (1.03–4.61) | .028 | 2.12 (1.05–4.25) | .035 |

| Sex (Male) | 0.69 (0.34–1.44) | .296 | 0.67 (0.34–1.34) | .264 |

| Age | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | .273 | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | .403 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval. Adjusted OR: adjusted for age, and sex.

This study aimed to determine the association between H. pylori infection and iron deficiency anemia. The study results showed that there was a significant association between H. pylori infection and anemia, and iron deficiency, and the rate of iron deficiency anemia in H. pylori-infected individuals was significantly higher than that in the H. pylori-uninfected individuals.

There was a significant relationship between H. pylori infection and iron deficiency in this study (aOR=2.12, 95% CI=1.05–4.25, P=.035). This finding is consistent with many previous studies.9,10,14,18,28–30 However, this present study found a discrepancy between changes in serum iron levels and serum ferritin levels in H. pylori-infected individuals. Both the serum iron and ferritin levels should be lower in the H. pylori-infected individuals compared to the H. pylori-uninfected ones due to iron deficiency related to H. pylori infection. However, only serum iron levels in H. pylori-positive individuals were significantly lower than those in H. pylori-negative individuals (59.4±42.1 μg/dL vs. 88.1±32.5 μg/dL, P<.001). In contrast, the median serum ferritin levels in the case group did not show significantly lower compared to the control group (103.5 [30.4–389.5] vs. 133.1 [56.6–224.1] (ng/mL), P=.623) in this study. This discrepancy was also reported in some studies.18,19,29,31 Hou et al. also noted no difference in serum ferritin levels between the H. pylori-infected group and the H. pylori-uninfected group (165.5 [109.80–272.75] vs. 186.10 [107.30–273.60], P=.903).20 Kishore et al. even noted that the serum ferritin level was higher in the H. pylori-infected group than in the H. pylori-uninfected group (536.82±117.0 ng/dL vs. 391.31±101.54 ng/dL, P<.001).32 This can be explained by the role of ferritin in the body which is a biomarker reflecting both the body's iron storage status and an inflammatory response. H. pylori infection causes a chronic inflammatory condition that increases ferritin levels, it consequently contributes to the normal or elevated serum ferritin levels despite iron deficiency arising from H. pylori infection.5,16,26,33

This study also found that the mean TSAT levels were less than 20% and the median ferritin levels were ≥100 ng/mL in H. pylori-infected individuals. High serum ferritin with low TSAT levels may imply dysutilization of iron for erythropoiesis.34 This condition can be caused by H. pylori infection which activates an inflammatory response mediated by Interleukin 6 leading to an increase in hepcidin. This substance binds ferroportin, a transmembrane protein found mainly in macrophages and enterocytes. This binding leads to cellular ferroportin internalization and degradation, subsequently decreasing iron availability for erythropoiesis. This is also a mechanism that contributes to the pathogenesis of anemia due to H. pylori infection.5

The association between H. pylori infection and anemia was also recorded in this study with aOR=7.59, 95% CI=3.83–15.05 (P<.001). This result is in line with previous studies.11,20,35–37 In addition, this study found that the cases of microcytic hypochromic anemia which occurred predominantly in H. pylori-infected individuals had mean RDW values of more than 14%. These findings indicate that iron deficiency is likely to be a cause of anemia in H. pylori-infected people.16,33,38 The predominance of microcytic hypochromic anemia in the case group is not in agreement with some studies.13,20 These studies reported normocytic normochromic anemia arising from H. pylori-infected individuals. This could be explained that iron deficiency anemia is detected in an early stage in these studies, thus MCV and MCH indices are not much affected.16,26 In addition, coexisting vitamin B12 deficiency which is caused by gastritis due to H. pylori infection can result in anemia without microcytosis despite existing iron deficiency.13,26

There was no case of iron deficiency anemia found in the control group, so our study only compared the rate of iron deficiency anemia between the 2 groups with a chi-square test instead of using multivariate regression analysis to identify the association between them. This study noted that the rate of iron deficiency anemia in H. pylori-infected people was significantly higher than that in H. pylori-uninfected people (13% vs. 0%, χ2=16.05, P<.001). Furthermore, H. pylori infection significantly associated with iron deficiency and anemia were found in the present study as described above. Microcytic hypochromic anemia, a type of anemia caused by iron deficiency, predominated in the cases of anemia occurring in H. pylori-infected individuals as well. These findings suggest a potential relationship between H. pylori infection and iron deficiency anemia. The association between H. pylori infection and iron-deficiency anemia has also been demonstrated in previous studies.6,7,9,12 However, in this study, the ferritin levels did not show a significant difference between the H. pylori-infected group and the H. pylori-uninfected group, and the IQR of median ferritin levels in the case group was wider than that in the control group. Therefore, iron deficiency as the primary cause of anemia in H. pylori-infected patients has not been conclusively established. The anemia in individuals infected with H. pylori may be caused by iron deficiency, chronic H. pylori infection, or a combination of both in the present study. Further studies are needed to ascertain whether iron deficiency is the primary cause of anemia in H. pylori-infected individuals or not.

The exact mechanism of iron deficiency anemia in patients with H. pylori infection remains unclear. However, there are several mechanisms through which H. pylori infection results in iron deficiency anemia that have been investigated. First, gastritis caused by H. pylori infection leads to decreased levels of ascorbic acid and stomach acidity. These in turn contribute to decreased absorption of dietary iron and thus the pathogenesis of iron deficiency anemia.4,5,12 The CagA-positive H. pylori strains were presumed to have a relationship with reduced levels of ascorbic acid in the stomach.12 Second, H. pylori require iron for their growth, so bacteria will increase iron acquisition directly from the stomach’s contents, consequently reducing the iron amount available to the host.4,5,12H. pylori can directly acquire iron by sequestering lactoferrin from the gastric mucosa of the host through a receptor for lactoferrin in its membrane.5 Third, bleeding from peptic ulcers and hemorrhagic gastritis caused by H. pylori are other possible mechanisms that can cause or contribute to iron deficiency.4,5,12 Finally, the role of hepcidin as presented earlier which contributes to the dysutilization of iron for erythropoiesis is a possible explanation of iron deficiency anemia due to H. pylori infection.5 The mechanisms of H. pylori infection leading to iron deficiency anemia mentioned above also imply that iron deficiency anemia can occur in both symptomatic and asymptomatic H. pylori infections.5,12 This may be meaningful in clinical practice, the screening for iron deficiency anemia should be performed in persons infected with H. pylori regardless of their clinical manifestations.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify the association between iron deficiency anemia and H. pylori infection in the Vietnamese population. However, this study had some limitations. Firstly, the sample size was relatively small as compared to previous studies, which may have affected the significance of the results. However, a sample size of 115 cases and 115 controls is still sufficient to yield meaningful results. Furthermore, the study was conducted using rigorous methods, with accurate data collection and appropriate statistical analysis. It was conducted at the University Medical Center, so the results can be considered valid for the study population. Secondly, the study did not test fecal occult blood for upper gastrointestinal bleeding to rule out cases of anemia due to blood loss, and measurement of sTfR (soluble transferrin receptor) has not yet been performed to distinguish between anemia caused by iron deficiency and anemia caused by chronic disease or inflammation. Finally, the study results just show the significant association between H. pylori infection and anemia; the cohort study is needed to identify whether H. pylori infection is a cause of iron deficiency anemia.

ConclusionsThis study has shown a significant association between H. pylori infection and anemia, and iron deficiency. The relationship between H. pylori and iron deficiency anemia remains inconclusive and needs further studies. However, these results remain meaningful in the context that the prevalence of H. pylori infection is still high, and iron deficiency anemia is a health problem in Vietnam as well. The study results suggest that tests for iron deficiency anemia should be performed routinely in the management of individuals infected with H. pylori.

Financial support and sponsorshipNone.

We highly appreciate the support from the University Medical Center Ho Chi Minh City - Branch 2.