Rapid tests for diagnosing Chlamydia trachomatis infection can facilitate patient treatment and reduce transmission, as patients can receive treatment during the same visit. This study aims to evaluate the performance of the rapid test compared to the PCR test for diagnosing C. trachomatis infection to assess its clinical applicability.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was conducted on participants aged >18 years with symptoms of genital discharge. The performance of the rapid test was evaluated using the PCR test as the gold-standard.

ResultsA total of 196 eligible patients were selected for the study. Females accounted for 68.4%, and those aged over 25 years represented 73.0% of the total. The prevalence of C. trachomatis infection was 14.3%. The overall return rate was 41.8%. The Chlamydia rapid test demonstrated a sensitivity of 53.6% (95% CI: 46.6–60.5%), specificity of 86.3% (95% CI: 81.5–91.1%), positive-predictive value of 39.5% (95% CI: 32.6–46.3%), and negative-predictive value of 91.8% (95% CI: 87.9–95.6%). The sensitivity of the rapid test was significantly higher in females, ≥25 years, those with past STIs, and symptoms including pruritus, dysuria, and purulent discharge than their counterparts (p<.05).

ConclusionWhile the Chlamydia rapid test is less sensitive than the PCR test, it is easy to implement, cost-effective, provides quick results, and allows more patients to receive treatment during the same visit compared to the PCR test. The rapid test still holds value in managing C. trachomatis infection in resource-limited settings, particularly with a low return rate.

Las pruebas rápidas para diagnosticar la infección por Chlamydia trachomatis pueden facilitar el tratamiento del paciente y reducir la transmisión, ya que los pacientes pueden recibir tratamiento durante la misma visita. Este estudio tiene como objetivo evaluar el rendimiento de la prueba rápida en comparación con la prueba de PCR para diagnosticar la infección por C. trachomatis y evaluar su aplicabilidad clínica.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio transversal en participantes mayores de 18 años con síntomas de secreción genital. El rendimiento de la prueba rápida se evaluó utilizando la prueba de PCR como estándar de oro.

ResultadosSe seleccionaron un total de 196 pacientes elegibles para el estudio. Las mujeres representaron el 68.4%, y aquellos mayores de 25 años representaron el 73.0% del total. La prevalencia de la infección por C. trachomatis fue del 14.3%. La tasa general de retorno fue del 41.8%. La prueba rápida de Chlamydia demostró una sensibilidad del 53.6% (IC del 95%: 46.6–60.5%), especificidad del 86.3% (IC del 95%: 81.5–91.1%), valor predictivo positivo del 39.5% (IC del 95%: 32.6–46.3%) y valor predictivo negativo del 91.8% (IC del 95%: 87.9–95.6%). La sensibilidad de la prueba rápida fue significativamente mayor en mujeres, ≥25 años, aquellos con ITS anteriores y síntomas que incluían prurito, disuria y secreción purulenta que en sus contrapartes (p < 0.05).

ConclusiónAunque la prueba rápida de Chlamydia es menos sensible que la prueba de PCR, es fácil de implementar, rentable, proporciona resultados rápidos y permite que más pacientes reciban tratamiento durante la misma visita en comparación con la prueba de PCR. La prueba rápida aún tiene valor en el manejo de la infección por C. trachomatis en entornos con recursos limitados, especialmente con una baja tasa de retorno.

Chlamydia trachomatis (C. trachomatis) infection is among the most common sexually transmitted diseases.1–3 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates 127.2 million new cases of C. trachomatis infection in 2019.4C. trachomatis imposes a significant burden on morbidity and the economy worldwide.1 It predominantly affects sexually active young individuals, notably those under the age of 25.1,2,4,5C. trachomatis causes cervical infection in females and urethral infection in males, as well as extra-genital infections including rectal and throat infections.1,6,7C. trachomatis infection often presents without symptoms, with approximately 70% of females and 50% of males.1,5–7 Untreated C. trachomatis infection can lead to serious complications, primarily in females, including pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, and infertility.1,6–8 In pregnant women, C. trachomatis infection can lead to severe consequences in newborns such as stillbirth, pre-term birth, low birth weight, conjunctivitis, and pneumonia.1,6,7 In males, the consequences may include epididymitis, which can lead to infertility.6,7 Furthermore, C. trachomatis infection increases the risk of contracting other sexually transmitted diseases and facilitates disease transmission to sexual partners.6,7 Therefore, accurate and effective diagnosis of C. trachomatis infection plays a crucial role in managing the disease and controlling its transmission within the community.4

Diagnosing C. trachomatis infection using nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) is currently considered the reference test.1,9,10 However, NAATs require well-trained personnel, specific equipment, a long turnaround time for results, and are expensive. Therefore, NAATs may not be suitable for facilities with limited resources.4,11 WHO has proposed an appropriate and effective test approach for identifying sexually transmitted infections, including C. trachomatis.12 Point-of-care (POC) tests are recommended to meet the ASSURED criteria (Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and Robust, Equipment-free, Delivered to end-users).12 Currently, rapid diagnostic tests for C. trachomatis fall into 2 categories: those based on NAAT (NAAT-based POC tests) and on antigen (AG-based POC tests).13 NAAT-based POC tests provide quick results with high sensitivity and specificity but still require sophisticated equipment, and well-trained staff, and are costly. Therefore, their utility is limited in resource-constrained settings.13,14 Antigen-based POC tests offer the advantage of simplicity, ease of use, visual result interpretation, and low costs, meeting the ASSURED criteria for point-of-care diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).15 Antigen-based POC tests are limited by their lower sensitivity.16 Nonetheless, they are still useful in settings with low return rates, as the number of cases treated increases when compared to highly sensitive tests with longer turnaround times.17

In Vietnam, rapid tests for diagnosing C. trachomatis infection have been used for a long time. However, the assessment of the performance of rapid tests is limited and often relies on manufacturer's evaluations. This has affected the management of the disease, potentially leading to missed cases or unnecessary treatments. This study aims to determine the performance of antigen-based rapid tests compared to polymerase chain reaction test (PCR test) in diagnosing C. trachomatis infection, with the goal of assessing the applicability of Chlamydia rapid test in the management of C. trachomatis infection.

Materials and methodsStudy designThe cross-sectional study was conducted on patients who attended the outpatient department at the HCMC Hospital of Dermato-Venereology from October 2022 to April 2023.

Study participantsInclusion criteria: (1) aged over 18; (2) presenting with vaginal or urethral discharge symptoms; (3) consenting to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria: (1) recent antibiotic treatment within 21 days; (2) pregnant women, those currently menstruating or using vaginal medication or douches or vaginal hygiene products within 48 h; (3) patients with severe underlying conditions that may jeopardize their safety during study participation.

Sampling techniqueThe sample size was estimated based on a predicted sensitivity of 73.6%, a specificity of 81.8%, and an estimated prevalence of 40%, according to Nilasari's study.18 The calculated sample size was 190. Participants were selected using systematic random sampling. The estimated average number of patients attending the clinic during the study period was 600, resulting in a sampling interval (k) of 3 (k=600/190). This means that every third patient attending the clinic would be screened and selected for the study.

Data collectionParticipants' demographic data including age, gender, occupation, residence, education, marital status; data related to sexual behavior; and clinical data were collected on data form. Participants were advised not to urinate for 1 h before sample collection. Each participant had 2 samples collected (urethral swab for males and cervical swab for females). The first sample was used for rapid test, and the second sample was used for PCR test. Rapid test samples were stored at room temperature and tested immediately. PCR test samples were stored at 2–8 °C at the collection site and transported to the laboratory, where they were stored at −20 °C. The PCR test was used as the standard test to assess the performance of the rapid test.

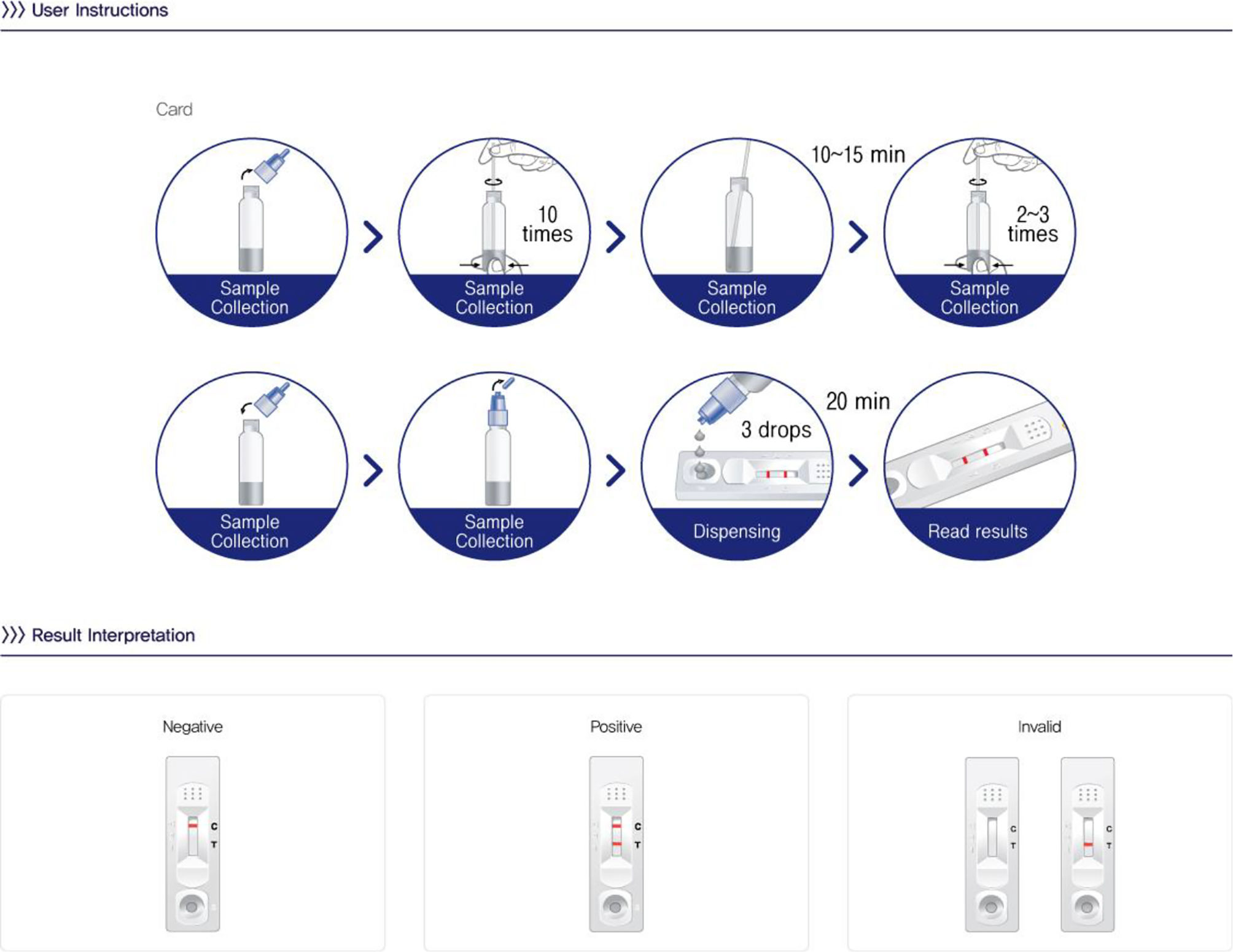

Chlamydia rapid testThe Chlamydia test card (One Step Chlamydia, Humasis, Korea) utilized an immunochromatographic principle to detect lipopolysaccharides (LPS) antigens of C. trachomatis. The test was performed following the manufacturer's instructions (as depicted in Fig. 1). The results were visually assessed 20 min after adding the sample extract to the sample well. A positive result was confirmed by the presence of 2 purple lines (C line and T line) in the result window. A negative result was indicated if only the C line appeared in the result window. Results were considered invalid if only the T line appeared without the C line. The Chlamydia rapid test results were provided to the patient within 45 min. The cost of one rapid test is about 4 USD (equivalent to 1/7 of the cost of a PCR test).

PCR testThe PCR test was conducted in 2 stages, DNA extraction and real-time PCR reaction. The DNA extraction process was carried out using the PANAMAX™ 48 automated extraction device (Pangene, Korea) with the PANAMAXTM Viral DNA/RNA Extraction Kit. The real-time PCR reaction was performed using the real-time PCR QuantStudio 5 Dx machine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, American) with the PANA RealTyper TM test kit (Pangene, Korea). The procedures were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The results were yielded between 3 and 4 h, and the PCR test results were delivered to the patients within 1–3 days. The cost of one PCR test is about 29.5 USD.

Ethical considerationsAll participants were provided with information about the study and signed informed consent before participating in the study. Participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences. Patient information was encoded and kept confidential. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Biomedical Research of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City under reference number 772/HĐĐĐ-ĐHYD, dated October 24, 2022.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using STATA version 15.1. Categorical variables will be presented as percentages (%). Proportions will be compared using the chi-square test. The value of the rapid test compared to the PCR test will be assessed in terms of sensitivity, specificity, positive-predictive value, negative-predictive value with 95% confidence interval (CI), and the Youden index. A p-value <.05 will be considered statistically significant.

ResultsA total of 196 cases meeting the study criteria were included in the study. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the study population and compares the characteristics between the C. trachomatis-infected and non-infected groups. The female-to-male ratio was 2:1. The proportion of individuals over 25 years old was much higher than that of those under 25 (73.0% vs 27.0%). Urban residence was predominant (67.9%), the most common occupation in the study population is self-employed, followed by office staff, with farmers being the least common. More than half of the study population had an educational level beyond high school (55.6%). Nearly half of the study population was married. About 41.3% of cases had a sexually transmitted infection in the past 12 months. The proportion of cases regularly using condoms was twice as high as that of cases who had not used condoms in the past 12 months.

Baseline characteristics of participants and comparison of characteristics according to C. trachomatis infection status.

| Variables | Overall | C. trachomatis infection | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=28) | No (n=168) | |||

| (n, %) | (n, %) | (n, %) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 62 (31.6) | 13 (46.4) | 49 (29.2) | .069a |

| Female | 134 (68.4) | 15 (53.6) | 119 (70.8) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Under 25 | 53 (27.0) | 7 (25.0) | 46 (27.4) | .793a |

| Over 25 | 143 (73.0) | 21 (75.0) | 122 (72.6) | |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 133 (67.9) | 17 (60.7) | 116 (69.0) | .382a |

| Rural | 63 (32.1) | 11 (39.3) | 52 (31.0) | |

| Occupation | ||||

| Farmer | 6 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.6) | .342b |

| Worker | 22 (11.2) | 5 (17.9) | 17 (10.1) | |

| Office staff | 48 (24.5) | 10 (35.7) | 38 (22.6) | |

| Seller | 34 (17.3) | 3 (10.7) | 31 (18.5) | |

| Student | 24 (12.2) | 4 (14.3) | 20 (11.9) | |

| Self-employed | 62 (31.6) | 6 (21.4) | 56 (33.3) | |

| Education | ||||

| Primary school | 39 (19.9) | 6 (21.4) | 33 (19.6) | .678a |

| Secondary, high school | 48 (24.5) | 5 (17.9) | 43 (25.6) | |

| College and above | 109 (55.6) | 17 (60.7) | 92 (54.8) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 106 (54.1) | 19 (67.9) | 87 (51.8) | .114a |

| Married | 90 (45.9) | 9 (32.1) | 81 (48.2) | |

| STIs in the past 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 81 (41.3) | 15 (53.6) | 66 (39.3) | .155a |

| No | 115 (59.7) | 13 (46.4) | 102 (60.7) | |

| Condom use | ||||

| Yes | 130 (66.3) | 18 (64.3) | 112 (66.7) | .805a |

| No | 66 (33.7) | 10 (35.7) | 56 (33.3) | |

| Urogenital symptoms | ||||

| Pruritus | 126 (64.3) | 19 (67.9) | 107 (63.7) | .670a |

| Dysuria | 69 (35.2) | 21 (75.0) | 48 (28.6) | .001a |

| Purulent discharge | 115 (58.7) | 23 (82.1) | 92 (54.8) | .006a |

| Erythema | 38 (19.4) | 10 (35.7) | 28 (16.7) | .018a |

| Return rate within 7 days (Yes) | 82 (41.8) | 14 (50.0) | 68 (40.5) | .344a |

The prevalence of C. trachomatis infection confirmed by PCR test was 14.3% (28/196). There was no statistically significant difference in the infection rate between genders, age groups, places of residence, educational level, occupation, marital status (p>.05). Similarly, the prevalence of C. trachomatis infection did not differ significantly between the group with a history of sexually transmitted infections and the group without such a history, as well as between the group that regularly used condoms and the group that did not use condoms regularly in the past 12 months (p>.05).

Regarding the patient's symptoms, pruritus was the most common symptom (64.3%), followed by purulent discharge (58.7%), and the least common was vaginal or urethral erythema (19.4%). There was no significant difference in the rate of pruritus between the C. trachomatis-infected group and the C. trachomatis-uninfected group (p>.05), but there was a significant difference in the rates of dysuria, purulent discharge, and vaginal or urethral erythema between the two groups with and without C. trachomatis infection (p<.05).

The return rate for a follow-up within 1 week was 41.8%, with a return rate of 50% in the C. trachomatis-infected group. Only 14 patients out of the total 28 patients infected with C. trachomatis confirmed by PCR test returned and received treatment.

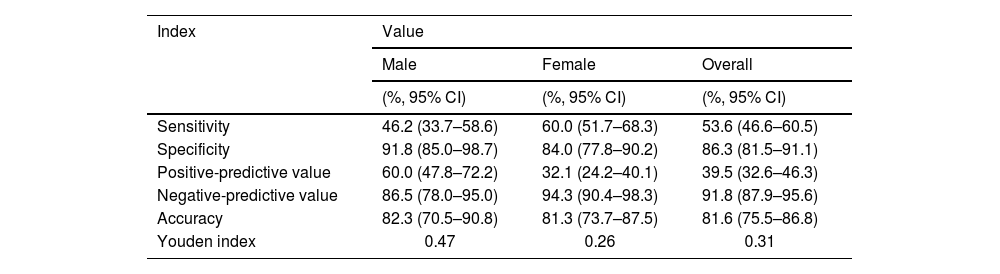

The performance of the Chlamydia rapid test compared to PCR is presented in Table 2. The sensitivity of the rapid test was moderate at 53.6% (95% CI: 46.6–60.5), with a relatively high specificity of 86.3% (95% CI: 81.5–91.1). The negative predictive value was high at 91.8% (95% CI, 87.9–95.6), and the Youden index was under 0.5. The concordant rate between the Chlamydia rapid test and PCR was 81.6% (Fig. 2).

Performance of Chlamydia rapid test versus polymerase chain reaction test.

| Index | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Overall | |

| (%, 95% CI) | (%, 95% CI) | (%, 95% CI) | |

| Sensitivity | 46.2 (33.7–58.6) | 60.0 (51.7–68.3) | 53.6 (46.6–60.5) |

| Specificity | 91.8 (85.0–98.7) | 84.0 (77.8–90.2) | 86.3 (81.5–91.1) |

| Positive-predictive value | 60.0 (47.8–72.2) | 32.1 (24.2–40.1) | 39.5 (32.6–46.3) |

| Negative-predictive value | 86.5 (78.0–95.0) | 94.3 (90.4–98.3) | 91.8 (87.9–95.6) |

| Accuracy | 82.3 (70.5–90.8) | 81.3 (73.7–87.5) | 81.6 (75.5–86.8) |

| Youden index | 0.47 | 0.26 | 0.31 |

The sensitivity of the Chlamydia rapid test varied with age, gender, history of past STIs, and clinical symptoms. Females, participants over 25 years old, those with a history of past STIs, and participants with symptoms such as pruritus, dysuria, and purulent discharge had significantly higher sensitivity in the Chlamydia rapid test compared to their counterparts (60.0% vs 46.2%; 57.1% vs 42.9%; 61.5% vs 46.7%; 63.2% vs 33.3%; 71.4% vs 47.6%; 80.0 vs 47.8%, respectively, p<.05) (Table 3).

Performance of Chlamydia rapid test according to age, gender, and clinical symptoms.

| Sensitivity (%, 95% CI) | Specificity (%, 95% CI) | PPV (%, 95% CI) | NPV (%, 95% CI) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 46.2 (33.7–58.6) | 91.8 (85.0–98.7) | 60.0 (47.8–72.2) | 86.5 (78.0–95.0) | .001 |

| Female | 60.0 (51.7–68.3) | 84.0 (77.8–90.2) | 32.1 (24.2–40.1) | 94.3 (90.4–98.3) | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Under 25 | 42.9 (29.5–56.2) | 89.1 (80.8–97.5) | 37.5 (24.5–50.5) | 91.1 (83.5–98.8) | .046 |

| Over 25 | 57.1 (49.0–65.3) | 85.3 (79.4–91.1) | 40.0 (32.0–48.0) | 92.0 (87.6–96.5) | |

| Past STIs | |||||

| Yes | 61.5 (52.7–70.4) | 87.3 (81.2–93.4) | 38.1 (29.2–47.0) | 94.7 (90.6–98.8) | .024 |

| No | 46.7 (35.8–57.5) | 84.9 (77.0–92.7) | 41.2 (30.5–51.9) | 87.5 (80.3–94.7) | |

| Condom use | |||||

| Yes | 55.6 (47.0–64.1) | 84.8 (78.7–91.0) | 37.0 (28.7–45.3) | 92.2 (87.6–96.8) | .493 |

| No | 50.0 (37.9–62.1) | 89.3 (81.8–96.8) | 45.5 (33.4–57.5) | 90.9 (84.0–97.8) | |

| Urogenital symptoms | |||||

| Pruritus | |||||

| Yes | 63.2 (54.7–71.6) | 88.8 (83.3–94.3) | 50.0 (41.3–58.7) | 93.1 (88.7–97.6) | <.001 |

| No | 33.3 (22.3–44.4) | 82.0 (73.0–91.0) | 21.4 (11.8–31.0) | 89.3 (82.0–96.5) | |

| Dysuria | |||||

| Yes | 71.4 (63.6–79.3) | 90.0 (84.8–95.2) | 29.4 (21.5–37.3) | 98.2 (95.9–99.9) | <.001 |

| No | 47.6 (35.8–59.4) | 77.1 (67.2–87.0) | 47.6 (35.8–59.4) | 77.1 (67.2–87.0) | |

| Discharge | |||||

| Purulent | 80.0 (71.3–88.7) | 82.1 (86.2–98.0) | 40.0 (29.3–50.7) | 98.6 (96.0–99.9) | <.001 |

| Mucus | 47.8 (38.7–57.0) | 81.5 (74.4–88.6) | 39.3 (30.4–48.2) | 86.2 (79.9–92.5) | |

| Erythema | |||||

| Yes | 55.6 (47.8–63.3) | 85.7 (80.3–91.2) | 33.3 (26.0–40.7) | 93.8 (90.0–97.5) | .494 |

| No | 50.0 (34.1–65.9) | 89.3 (79.5–99.1) | 62.5 (47.1–77.9) | 83.3 (71.5–95.2) | |

The cross-sectional study was conducted on patients presenting with symptoms of vaginal or urethral discharge to evaluate the performance of the antigen-based rapid test for C. trachomatis in comparison to the standard PCR test, with the goal of assessing the applicability of the rapid test in clinical practice.

The study results showed a prevalence of C. trachomatis infection at 14.3%. This rate is significantly higher than the figures in the general population in many previous studies.1,2,4,19–22 It is also higher than the C. trachomatis infection rates in the Southeast Asia region reported by Huai et al.3 However, this rate is lower than the rates found in high-risk populations in the studies conducted by Nilasari et al (46.3%)18 and by Saison et al (17.9%–32.0%).23 These differences can be explained by the population in our study, which included individuals with symptoms of genitourinary infection but not belonging to the high-risk groups. Given the high prevalence of C. trachomatis in this study, C. trachomatis infection is a health issue that needs to be addressed in Vietnam.

This study observed that symptoms such as dysuria, purulent discharge, and vaginal or urethral erythema were significantly higher in cases of C. trachomatis infection (p<,05). These symptoms have also commonly been described in the literature regarding C. trachomatis infection.1,4,6,7 Furthermore, this study noted the return rate in the study population at 42%, with C. trachomatis-infected patients having a return rate of 50.0%. This rate is higher than the study by Sabido et al24 (38%) but still lower than the 65% level. This level was noted in the study by Gift et al. They reported that more cases of infection identified by rapid test were treated compared to cases identified by PCR test if the return rate is less than 65%.17

The study results showed that there was a concordance rate of 81.6% between the Chlamydia rapid test and PCR test, with the sensitivity and specificity of the rapid test compared to PCR being 53.6% and 86.3%, respectively. These findings are consistent with other studies23,25,26 and reviews on the performance of antigen-based rapid tests for diagnosing C. trachomatis.11,14,16,27–31 These studies demonstrated that the sensitivity of antigen-based rapid tests was moderate. Although some studies have shown a higher sensitivity of antigen-based rapid tests, such as Nilasari et al. with a sensitivity of 73.6%,18 and Mahilum-Tapay et al. with a sensitivity of 83.5%,32 overall, the sensitivity of antigen-based rapid tests is lower than the WHO's target for the minimal clinical sensitivity of POC tests for C. trachomatis, which is 90%.15 The reason for the low sensitivity of antigen-based rapid tests is that C. trachomatis is an intracellular pathogen that can inhibit the host cell's defense functions to enter and survive within neutrophil and macrophage cells. As a result, antigen-based rapid tests cannot fully expose all antigens of the pathogen, leading to limited sensitivity in antigen-based rapid tests.29

In this study, variations in the sensitivity of the rapid test were also observed in different subgroups. Cases involving females, participants over 25 years of age, with a history of past STIs, and with symptoms such as pruritus, dysuria, and purulent discharge showed significantly higher sensitivity in the rapid tests compared to the control subgroups (p<.05). This can be explained by the fact that the sensitivity of rapid tests depends on the bacterial load, and patients with these characteristics often have a higher bacterial load, which increases the sensitivity of the rapid test.9,29,32 This finding suggests that the cases with these characteristics should be recommended to undergo rapid tests for the diagnosis of C. trachomatis in clinical practice.

Due to the low sensitivity of antigen-based rapid tests, NAAT (Nucleic Acid Amplification Test) is considered the standard test for diagnosing and screening C. trachomatis infection.1,10,33 However, performing NAATs requires complex equipment, trained personnel, high costs, and long turnaround times.11,29 Meanwhile, antigen-based rapid tests are easy to perform, provide results that can be read visually, have a quick turnaround time, and are cost-effective. Antigen-based rapid tests meet the ASSURED criteria, except for their relatively low sensitivity. Additionally, given that rapid tests have a short turnaround time, the patients get their results during the same clinic visit and receive treatment immediately if the test results are positive. This will increase the number of patients receiving treatment if the rate of patients returning for follow-up is low, thereby reducing the risk of complications of the infection and onward transmission.4

Several studies have shown that the effectiveness of rapid tests for C. trachomatis in clinical practice has been affected by various factors beyond the sensitivity of the rapid test. Vickerman et al. used a mathematical model and found that the sensitivity of rapid tests for C. trachomatis doesn't need to be high if there is significant transmission during the delay in treatment for test results determined by NAAT and /or low return rate for treatment.34 For instance, the sensitivity of the rapid test for C. trachomatis only needs to be 50% if either the return rate is 55% and there is no infection transmission to others, or if the return rate is 80% and 50% of infected cases transmit the infection to their partner during the delay in treatment. Furthermore, Ronn et al employed mathematical modeling analysis to demonstrate that with a point-of-care test sensitivity of 90%, reductions in the disease burden only occur when the rate of screened individuals receive immediate treatment over 60%, and the loss to follow-up is 20%.35 Similarly, Gift et al. used a decision analysis of the test for C. trachomatis and found that when the return rate for follow-up is under 65% and the sensitivity of the rapid test is 63%, the number of treated cases detected through the rapid test is greater than with the PCR test alone.17

Similarly, the effectiveness of tests for C. trachomatis also depends on the time it takes to receive test results and the willingness of patients to wait for the test results. For instance, Lea et al. reported that 61% of patients were willing to wait for 20 min to get test results, but only 26% were willing to wait for 40 min for test results if they received treatment before leaving the clinic.36 Harding-Esch et al found that non-NAAT POC test results were available for all patients before leaving the clinic, while only 21.4% of patients received CT/NG GeneXpert NAAT results prior to leaving the clinic because they were not willing to wait for over 2 h to receive their test results.37 Mahilum-Tapay et al noted that with the Chlamydia rapid test, results available within 30 min would allow all cases with positive test results to receive treatment during the same clinic visit.32 Huang et al showed that sensitivity, cost, and the willingness of patients to wait for results are the key factors in determining the cost-effectiveness of rapid tests.38 Similarly, Yu-Hsiang et al reported that the important characteristics of rapid tests for clinical practice are sensitivity, cost, and turnaround time.39

Our study observed that the overall return rate within 7 days was low, around 42%. For C. trachomatis infected patients confirmed by PCR test, the return rate within 7 days was at 50%. Only 14 cases of C. trachomatis infection identified by PCR received treatment within 1 week. Despite receiving treatment, these cases still pose a risk of transmitting the infection to their sexual partners. On the other hand, with the rapid test, even though it has lower sensitivity, there would be 15 cases receiving immediate treatment during the same clinic visit, consequently reducing the risk of onward transmission. Through a cost-effective analysis of the rapid tests, as previously presented, even though the sensitivity of the rapid test in this study is around 53%, the Chlamydia rapid test is still valuable in clinical practice due to low cost (equivalent to 1/7 cost of a PCR test), ease of implementation, and short turnaround time (20 min), and especially in the context of low return rate of 42%. Given these aforementioned characteristics, the Chlamydia rapid test has contributed to treating more patients, reducing complications and disease-related consequences, and lowering the risk of onward transmission.4 The Chlamydia rapid test will be even more valuable in resource-limited settings like Vietnam.

This study has some limitations, including that it was only conducted on participants with symptoms of genitourinary infection, some participants may have been reluctant to provide complete information about risky sexual behaviors, and gene sequencing tests were not performed to validate the PCR test results. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies in Vietnam to assess the performance and applicability of Chlamydia rapid tests in clinical practice.

ConclusionsIn summary, this study demonstrates that the Chlamydia rapid test, despite having lower sensitivity compared to NAAT, remains a valuable application in clinical practice particularly in resource-limited settings, thanks to its cost-effectiveness, ease of implementation, and short turnaround time. This is especially true when the return rate for follow-up is low.

FundingNot applicable.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Biomedical Research of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City under reference number 772/HĐĐĐ-ĐHYD, dated 24/10/2022.

All participants volunteered to take part in the study and provided written informed consent before being recruited. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal upon request.

Credit authorship contribution statementThi Luyen Pham, Tuan Anh Nguyen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Viet Tung Le: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Manh Tuan Ha: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

We highly appreciate the support from the University Medical Center Ho Chi Minh City and HCMC Hospital of Dermato-Venereology.