We systematically reviewed the associations between allergic rhinitis or allergy and otitis media with effusion, by reference to published data.

Study designA meta-analysis of case-controlled studies.

Data sourceFive databases (Pubmed, Highwire, Medline, Wanfang, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure) were searched for relevant studies in the English language published prior to November 12, 2015.

Studies chosenStudies with clearly defined experimental and control groups, in which the experimental groups had otitis media with effusion together with allergic rhinitis or allergy, were selected.

MethodsWe performed a meta-analysis on data from the identified cross-sectional and case-controlled studies using fixed- or random-effects models (depending on heterogeneity). We used Reviewer Manager 5.3 software to this end.

ResultsSeven studies met the inclusion criteria. The prevalence of allergic rhinitis in patients with otitis media with effusion and the control groups differed significantly in three studies (P<0.00001), as did the prevalence of allergy (in six studies; P=0.003).

ConclusionAllergic rhinitis and allergy appear to be risk factors for otitis media with effusion.

Otitis media with effusion (OME) is globally common, with a prevalence of 8.7% in primary school children (152/1740).1 In children under six years of age visiting outpatient clinics, the prevalence of OME, Eustachian tube dysfunction (ETD), or tympanic membrane retraction (TMR) is 1.4%.2 The incidence of otitis media during the first two years of life does not differ between Caucasian and African American infants.3,4

The symptoms of OME are problematic, especially the decline in hearing level and the sensation of aural fullness. Children with OME suffer more than adults do.5,6 However, insertion of a pressure-equalising tube (PET) does not always cure OME.7 Identification of risk factors would be helpful to prevent OME in children. Many such risk factors have in fact been identified; these include genetic predisposition8; gastro-oesophageal reflux (in adult patients)9,10; rhinitis2; chronic rhinosinusitis2; adenoidal problems and adenoiditis11; allergic rhinitis (AR; 12, 13); asthma14; and allergies,14,15etc. The middle ear connects with the respiratory tract, and we thus presumed that AR or allergy may be mutually associated with OME.

We thus performed a meta-analysis to systematically explore whether AR or allergy correlates significantly with OME.

MethodsSearch strategyWe used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist.16,17 Two authors independently (and manually) searched for papers on OME and AR or allergy.

Five databases (Pubmed, Highwire, Medline, Wanfang, and CNKI [China National Knowledge Infrastructure]) were searched within the overall term “AR vs. OME” for all relevant papers published from March 1973 to November 12, 2015. The search subterms emphasised the possible relationship between AR and OME, and included “allergic rhinitis and otitis media with effusion;” “risk factors for otitis media with effusion;” and “allergic rhinitis comorbidity” (indicating that AR was a risk factor for OME). Within the general search term “allergy vs. OME” (indicating that allergy or atopy was a risk factor for OME), we used the subterms “allergy and otitis media with effusion” and “atopy and otitis media with effusion” to retrieve citations published from April 1956 to November 12, 2015. All related articles were retrieved. In addition, the two authors screened the reference lists of retrieved papers to further identify potentially relevant publications.

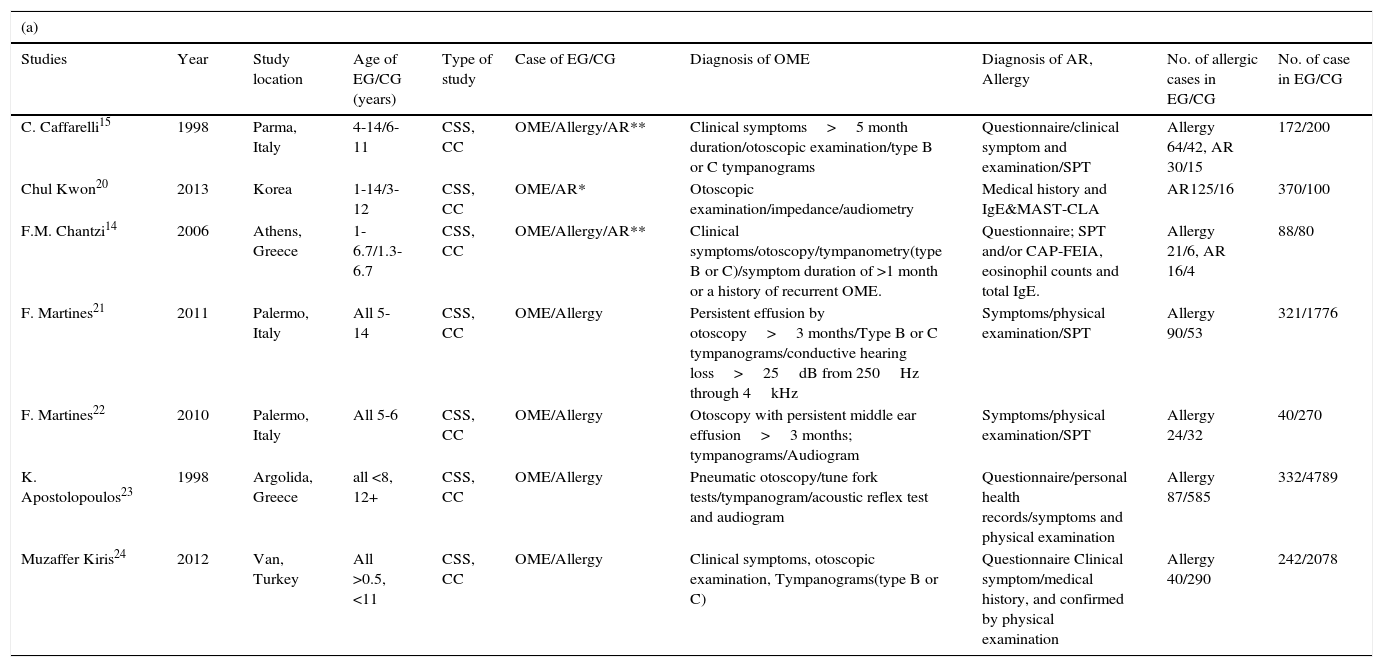

Definition and clinical criteria of OME, AR and allergyOME is characterised by the presence of mucoid effusion in the middle ear causing decreased mobility of the tympanic membrane and conductive hearing loss.1,5,6 Allergic rhinitis is defined when patients are allergic to at least one allergen resulting in nasal obstruction or congestion, rhinorrhoea, rhinocnesmus and sneezing.12,13 Allergy is defined as IgE-mediated allergic diseases.14,15 The diagnosis criteria of OME, AR and allergy were described in individual studies, which included case history, symptoms, physical examination and other examinations such as tympanogram, microscopic otoscopy or tympanostomy tube insertions, SPT or serum IgE test, etc. (Table 1).

Characteristics of the chosen studies and their participants, and quality assessments obtained using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

| (a) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | Year | Study location | Age of EG/CG (years) | Type of study | Case of EG/CG | Diagnosis of OME | Diagnosis of AR, Allergy | No. of allergic cases in EG/CG | No. of case in EG/CG |

| C. Caffarelli15 | 1998 | Parma, Italy | 4-14/6-11 | CSS, CC | OME/Allergy/AR** | Clinical symptoms>5 month duration/otoscopic examination/type B or C tympanograms | Questionnaire/clinical symptom and examination/SPT | Allergy 64/42, AR 30/15 | 172/200 |

| Chul Kwon20 | 2013 | Korea | 1-14/3-12 | CSS, CC | OME/AR* | Otoscopic examination/impedance/audiometry | Medical history and IgE&MAST-CLA | AR125/16 | 370/100 |

| F.M. Chantzi14 | 2006 | Athens, Greece | 1-6.7/1.3-6.7 | CSS, CC | OME/Allergy/AR** | Clinical symptoms/otoscopy/tympanometry(type B or C)/symptom duration of >1 month or a history of recurrent OME. | Questionnaire; SPT and/or CAP-FEIA, eosinophil counts and total IgE. | Allergy 21/6, AR 16/4 | 88/80 |

| F. Martines21 | 2011 | Palermo, Italy | All 5-14 | CSS, CC | OME/Allergy | Persistent effusion by otoscopy>3 months/Type B or C tympanograms/conductive hearing loss>25dB from 250Hz through 4kHz | Symptoms/physical examination/SPT | Allergy 90/53 | 321/1776 |

| F. Martines22 | 2010 | Palermo, Italy | All 5-6 | CSS, CC | OME/Allergy | Otoscopy with persistent middle ear effusion>3 months; tympanograms/Audiogram | Symptoms/physical examination/SPT | Allergy 24/32 | 40/270 |

| K. Apostolopoulos23 | 1998 | Argolida, Greece | all <8, 12+ | CSS, CC | OME/Allergy | Pneumatic otoscopy/tune fork tests/tympanogram/acoustic reflex test and audiogram | Questionnaire/personal health records/symptoms and physical examination | Allergy 87/585 | 332/4789 |

| Muzaffer Kiris24 | 2012 | Van, Turkey | All >0.5, <11 | CSS, CC | OME/Allergy | Clinical symptoms, otoscopic examination, Tympanograms(type B or C) | Questionnaire Clinical symptom/medical history, and confirmed by physical examination | Allergy 40/290 | 242/2078 |

| (b) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies/total stars | Selection (****) | Exposure (**) | Comparability (****) |

| C. Caffarelli15 | **** | ** | *** |

| Chul Kwon20 | *** | ** | *** |

| F. M. Chantzi14 | **** | ** | *** |

| F. Martines21 | **** | ** | *** |

| F. Martines22 | **** | ** | *** |

| K. Apostolopoulos23 | **** | ** | *** |

| Muzaffer Kiris24 | **** | ** | *** |

CSS, cross-sectional study; EG, experimental group; CG, control group; CC, case–control; SPT, skin prick test; MAST-CLA (multiple allergosorbent test-chemiluminescent assay).

A study was awarded a maximum of one star for each numbered item within the selection and exclusion categories. A maximum of two stars was awarded for comparability; a maximum of four for selection (****); a maximum of two for exposure (**).

All selected papers were carefully checked. The eligibility criteria for inclusion were: (a) case–control studies in which all experimental group (EG) members had OME; (b) the control groups (CGs) in all studies retrieved using the “AR vs. OME” and “allergy vs. OME” terms were fully or largely healthy (controls with preauricular fistulas, or [only] extremely severe sensorineural hearing loss, were acceptable); and (c) the studies were restricted to humans, published in English, and appeared in either full-text or abstract form.

We excluded studies using outpatients lacking OME as controls. All experimental groups had clearly defined OME (either unilateral or bilateral). Patients with eosinophilic otitis media, otitis media, chronic otitis media with cholesteatoma, or chronic refractory otitis media were excluded. Studies lacking adequate data, immunological or genetic analyses of associations between OME and AR, and studies on participants that had been included in prior works were excluded.

We set two further prerequisites. First, the full text clearly defined the experimental and control groups and, second, the numbers of group members and observational data were available. These allowed us to determine the odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Study quality and data analysisAll studies were case-controlled and cross-sectional in nature. In line with a suggestion of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), we used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) to assess individual study quality and the risk of bias.18 Review Manager 5.3 software was used to create Forest maps and funnel plots (these are principal summary measures). Either a fixed- or random-effects model was applied, depending on the P-value of the chi-squared statistic (a fixed-effects model when P was >0.05; a random-effects model when P was <0.05). An I2 value <25% was taken to indicate low heterogeneity and an I2 value >50% high heterogeneity.19 In the random-effects model used to analyse “allergy vs. OME,” we sought to perform a meta-regression using Stata12 software to determine the sources of heterogeneity. This was because the I2 value was >50% for the six relevant studies. However, meta-regression is not reliable if data from fewer than 10 studies are available; we thus do not present our data.

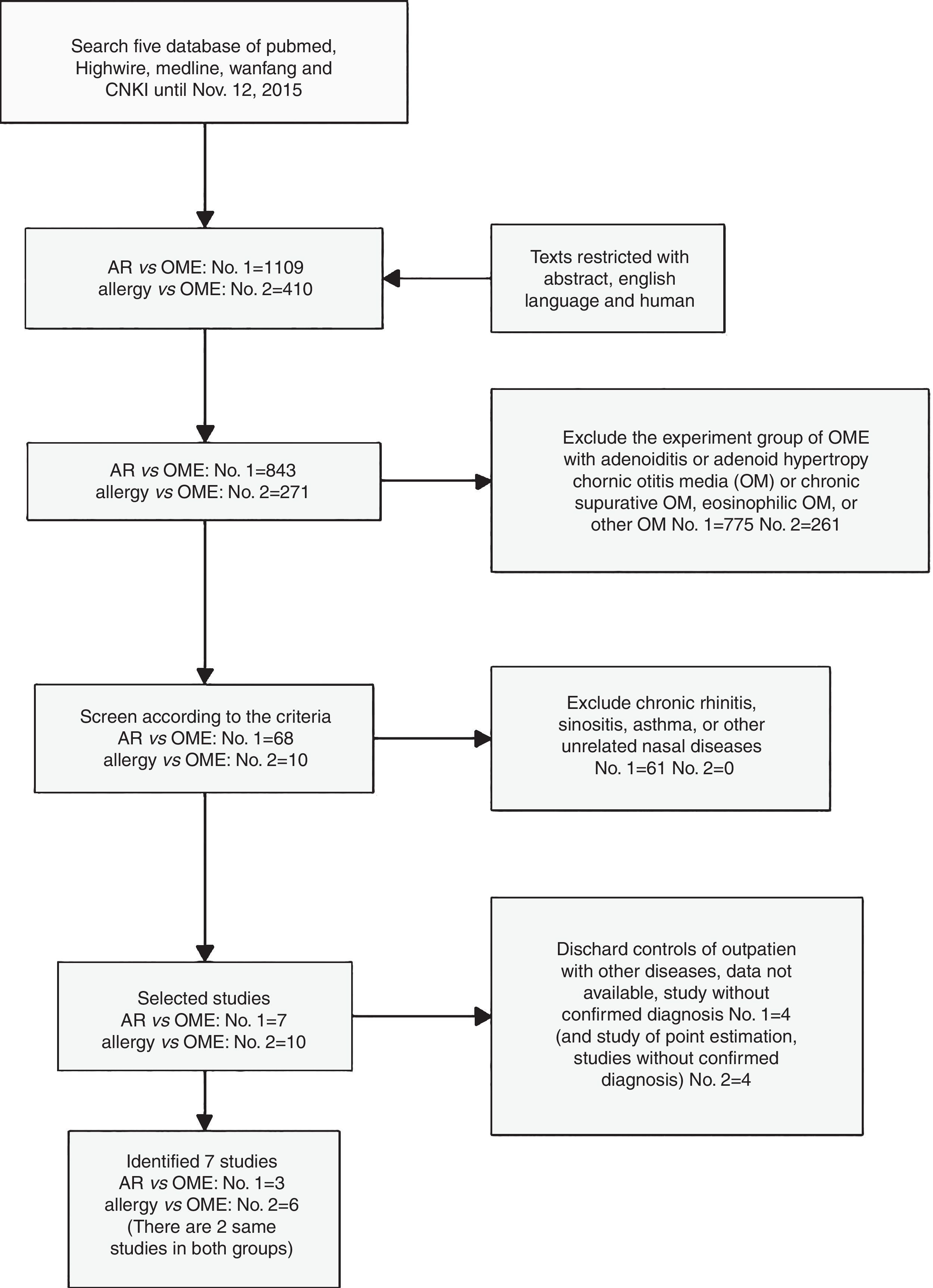

ResultsSearch resultsWe selected 68 of 843 papers retrieved using the term “AR vs. OME” and an additional 10 (of 271) papers retrieved using “allergy vs. OME.” Ultimately, seven publications met all of our inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis and our eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). Two studies were retrieved using both searches14,15; one only when searching “AR vs. OME”20; and four only when searching “allergy vs. OME”.21–24

Characteristics of the identified studiesAll studies had obtained the required ethical approval and informed consent of all patients and/or subjects. The studies compared the prevalence of AR or allergy in both OME patients and healthy populations. Table 1a summarises the characteristics of the seven studies. The participants were school-aged children aged from six months to 12+ years.

Three studies retrieved using “AR vs. OME” were small-group works, with 630 cases in the combined EGs and 380 in the CGs.14,15,20 Three studies retrieved using “allergy vs. OME” were large21,23,24 and the other three small.14,15,22 In total, 1233 patients were in the EGs and 4504 subjects in the CGs.

All OME cases were diagnosed by ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialists. The EGs of three studies14,15,20 were outpatients, and the rest, schoolchildren.21–24 AR and allergy were diagnosed in various ways in the seven studies. Five studies14,15,20–22 ran blood or skin prick tests (SPTs) in addition to medical history-taking and physical examination. The remaining studies used standardised questionnaires for diagnosis23,24 in addition to medical records, clinical symptoms and physical examination. The CGs of two studies14,20 were outpatients with or without minor illnesses (e.g., preauricular fistulas),14 and the remaining CGs were healthy schoolchildren.15,21–24

Quality assessmentWe assessed the quality of all seven studies using the NOS (Table 1b). All were cross-sectional case–control studies for which ethical approval had been obtained. Two large studies23,24 gave the numbers of excluded participants; the others did not. However, all studies used clear criteria and definitions when diagnosing OME, AR and allergy.

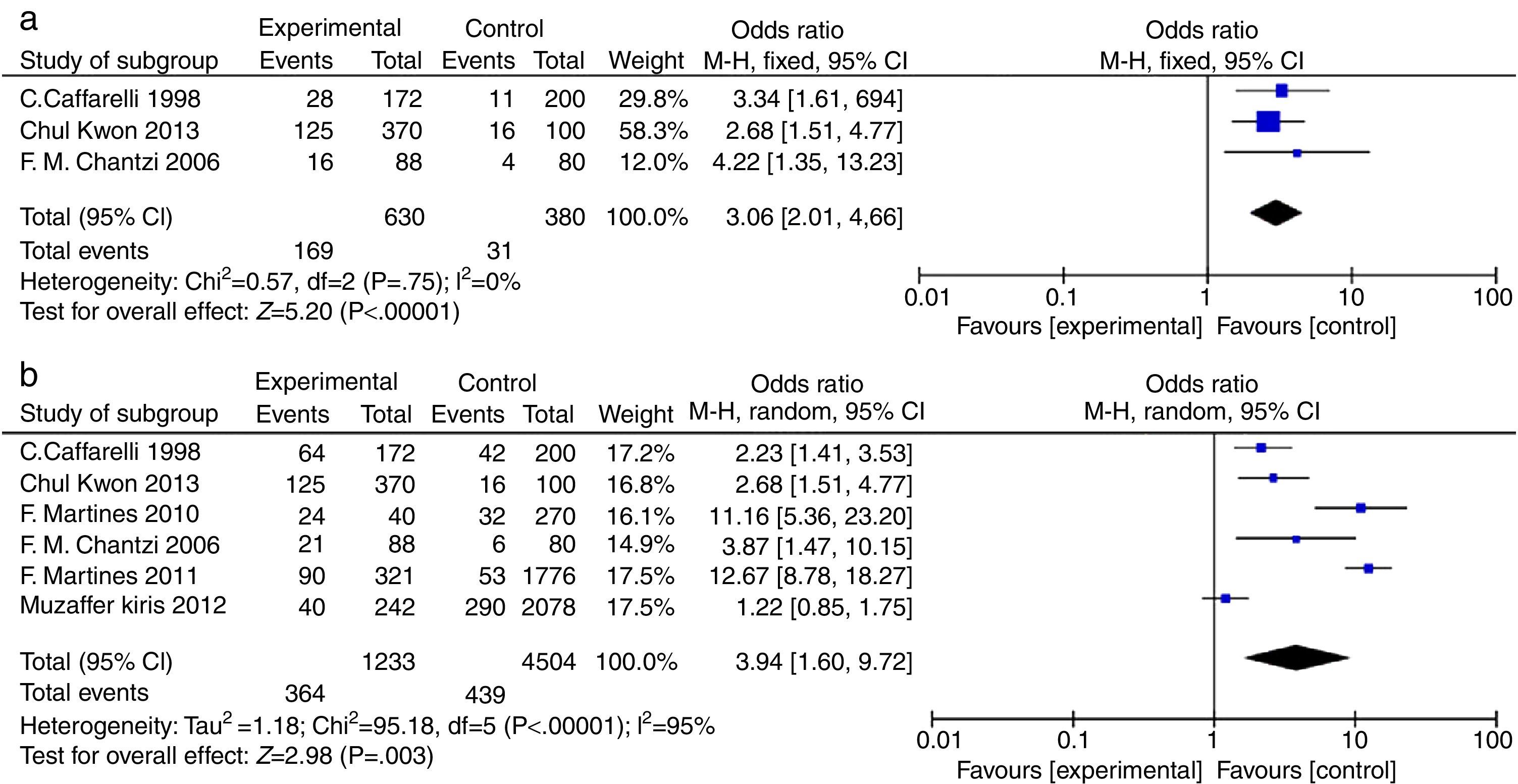

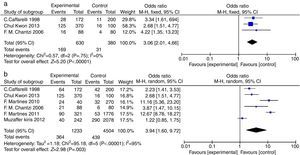

AR vs. OME analysisA total of 630 patients (in three studies) had OME, of whom 169 also had AR, whereas the 380 controls included 31 with AR (OR=3.06, 95% CIs: 2.01, 4.66; Fig. 2a). Clearly, AR was more prevalent in patients with OME; inter-study heterogeneity was essentially absent (Chi2=0.57, df=2 [P=0.75], I2=0%; Fig. 2a). The difference in AR prevalence was significant in the fixed-effects model (P<0.00001; statistical significance was set at P<0.05).

Participant data from studies included in the meta-analysis (AR vs. OME and allergy vs. OME). (a) AR vs. OME. Forest plots of the data of three studies; a fixed-effects method was used to compare AR patients in the EGs and CGs (P<0.00001). (b) Allergy vs. OME. Forest plots of the data of six studies; a random-effects method was used to compare AR patients in the EGs and CGs (P=0.003). Both P values indicate that AR and allergy are risk factors for OME. The level of statistical significance was set to P<0.05.

Six studies compared the prevalence of allergy in OME patients and healthy controls (Fig. 2b). In total, of 1233 OME patients, 364 had allergies compared to 439 of 4504 controls (OR=3.94, 95% CIs: 1.60, 9.72). However, significant inter-study heterogeneity was evident (Chi2=95.18, df=5 with P<0.00001, I2=95%; Fig. 2b). The difference in the prevalence of allergy was significant in the random-effects model (P=0.003, P<0.05).

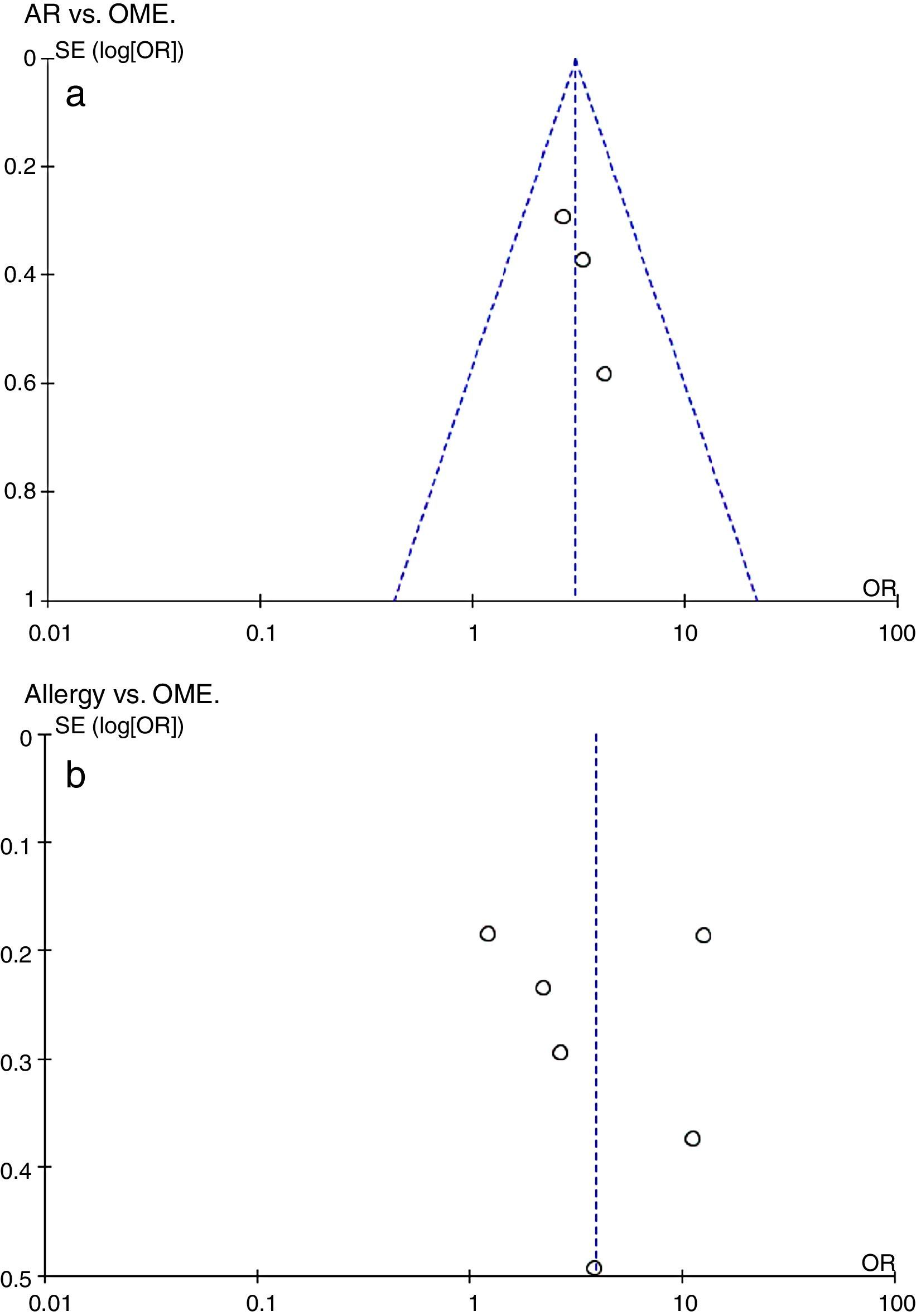

Additional analysesPotential bias was explored by constructing funnel plots (Fig. 3). Both groups were of normal intensity and relatively symmetrical, indicative of a low publication bias. Study heterogeneity of the AR vs. OME analysis was low (I2=0, I2<25%), but that of the allergy vs. OME analysis was very high (I2=95%, I2>50%). Only six studies met the allergy vs. OME criteria; thus, this was too few to identify the source(s) of heterogeneity via a meta-regression.

Evaluation of a potential publication bias. (a) AR vs. OME. Funnel plots evaluating publication bias in three studies. (b) Allergy vs. OME. Funnel plots evaluating publication bias in six studies. Both groups are of normal intensity and relatively symmetrical. SE, standard error; OR, odds ratio.

The relationship between OME and AR or allergy still requires further investigations. We sought to identify a correlation between AR and OME and analysed AR vs. OME and allergy vs. OME, as reported in short-term cross-sectional studies. Our results confirmed that both AR and allergy were significant risk factors for the development of OME, which were well supported. First, several authors have reported that allergen exposure induces OME symptoms. AR patients are predisposed to Eustachian tube obstruction (ETO) upon induction of local hypersensitivity, but normal controls are not.25 Furthermore, AR patients have high incidences of Eustachian tube dysfunction (P≤0.05).26 This could be explained by this study: exposure to allergens may disturb middle ear pressure via the induction of ETO, due to the more negative pressure upon antigen compared to control challenge.27 Second, there is also clear evidence that middle ear effusions can reflect a Th2 pattern of inflammation in both mouse model28 and OME patients.29 AR patients are susceptible to OME, and Th2 responses are evident in the middle ears of atopic patients. As is known, Th2 cells (effector T helper cells) drive inflammatory responses by eosinophils, neutrophils, and mast cells; the levels of such cells are significantly higher in atopic patients.12 The evidenced Th2 response in middle ear mucosa of OME indicates the allergic inflammation in OME. Higher proportions of Th2 cells express IL-4 (interleukin, IL) and IL-5 in atopic patients with OME than non-atopic patients.13 The mucosa of the nose and middle ear are similar, supporting the United Airway Concept (in which the middle ear is included; 30). Thus, the mucosa of the middle ear is as capable of an allergic response as is the remainder of the upper respiratory tract. In addition, AR or allergy may act on (simple) otitis media to first induce OME and, next, recurrent acute otitis media (RAOM). Allergy significantly prolongs the duration of OME, but not RAOM.30

However, the relation between OME and AR or allergy will remain controversial based on clinical evidences. A systemic review with 1880 participants demonstrated no benefit and some harm from the use of antihistamines or decongestants alone or in combination in the management of OME.31 Also, antihistamines, decongestants, or both intranasal steroids or systemic steroids for treating OME is recommended against in the guidelines of 2016 and 2004.32,33 There are also satisfactory clinical results approving their relationship. As AR may be a risk factor for OME, desensitisation would be expected to be effective since treating AR may reduce the risk of OME. Several authors have reported that nasal steroid spray is still used as an effective treatment for OME34 or OME with adenoidal hypertrophy,35 while Azelastine hydrochloride (AZ) helps cure OME symptoms in patients with both AR and OME,36 even though some still believe that allergic symptoms are not risk factors for OME.37 But upon desensitisation, 85% of AR patients with OME are cured, and another 5.5% of patients enter remission.38 It may be that allergic inflammation, but not mechanical nasal mucosal swelling, triggers OME development.39

Seven relevant case–control cross-sectional articles were retrieved, and a number of limitations of our meta-analysis warrant to be mentioned. First, the diagnosis criteria of OME and AR or allergy vary in these studies, and four included studies are small.14,15,20,24 One study clearly defined the OME with conductive hearing loss>25dB from 250Hz through 4kHz,23 and another two studies did not define their criteria of audiogram results.20,24 Serum IgE was not used for the confirmation of diagnosis of AR/allergy.15,21–24 All the identified studies were found to have a positive association with OME. But the quality of the included studies was variable, thus publication and outcome reporting biases may exist and may negatively affect the quality of data extracted for meta-analysis. Second, high-level inter-study heterogeneity was evident. We also aimed to identify the sources of heterogeneity using Stata 12 software (i.e., ethnicity and/or year of publication may have contributed to the observed heterogeneity; data not shown). However, a meta-regression cannot be reliably performed on data from fewer than 10 studies.

ConclusionOME and AR are prevalent in preschool and school-aged children. Our study suggests that AR and allergy are risk factors for OME. However, because the data is limited, of poor quality, and subject to significant risk of bias, the outcome should be treated cautiously. Further research on the relation of AR/allergy and OME need be undertaken. Our data indicates that some but not all OME cases may be associated with AR or allergy. If a child with OME has AR or an allergy, anti-allergy treatment may mitigate both the allergy and OME.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

FundingThis work was supported by the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (the 973 Program) (grant nos. 2011CB504506, NSFC 81271084 [to F.C.] and 81420108010 [to F.C.]). The work was also supported by grant no. NSFC 81371093 to Z.H and NSFC 81200738 to N. C.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

We thank all the authors of the identified studies and their co-workers: Caffarelli C, Chantzi FM, Kwon C, Martines F, Apostolopoulos K, Muzaffer K, et al.