To analyze the incidence of wheezing in the first six years of life; the prevalence of asthma at six years of age; and the associated risk factors, in a population from Valencia, Spain.

MethodsA prospective longitudinal study was made of a cohort of 636 newborn infants, with follow-up of the clinical records and the completion of questionnaires up to the age of six years.

ResultsThe prevalence of asthma at six years of age was 12.8%. Up until that age, 63% of the study population had experienced at least one episode of wheezing, and 35% had suffered recurrent wheezing (three or more episodes). Admission due to wheezing was associated to school asthma. The following risk factors were identified: atopic dermatitis (OR: 2.1; 95%CI: 1.2-3.5), the presence of at least one episode of wheezing in the first year (OR: 1.8; 95%CI: 1.1-2.9), prematurity (OR: 2.5; 95%CI: 1.2-5.1), and a family history of asthma (OR: 2.2; 95%CI: 1.2-4.1).

ConclusionsThe prevalence of asthma at six years of age in our population is similar to that described in other longitudinal studies. An important increase is observed in the cumulative incidence of wheezing and of recurrent wheezing up to three years of age, followed by stabilization. The most relevant risk factors for developing asthma at six years were atopic dermatitis, wheezing during the first year, prematurity, and a family history of asthma. Full-term pregnancy and the minimization of respiratory infections at an early age could reduce the prevalence of asthma at six years of age in our population.

Asthma is the most common chronic disease in childhood and the most frequent cause of hospital admission and visits to the emergency department.1 According to the results of the ISAAC (International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood), the prevalence of asthma at six years of age in the city of Valencia, Spain in the year 2002 was 9.3%, whilst the global Spanish national prevalence was 9.9%.2,3 In the TCRS (Tucson Children's Respiratory Study) reference longitudinal study, the prevalence of asthma at six years of age was 9.6%.4 In turn, 33.5% of the children in that cohort had wheezing during the first three months of life, most of them due to viral respiratory infections. Of these children, 60% developed no further episodes after that age, while the remaining 40% continued to suffer episodes up to six years of age.5

Determining when recurrent wheezing in the first years of life represents the clinical expression of future asthma is a challenge that could facilitate decision making in clinical practice and allow the implementation of specific prevention measures. In this regard, the investigators of the TCRS analyzed the risk factors associated to the diagnosis of asthma at six years of age, and found atopic dermatitis, a family history of asthma, sensitization to allergens and eosinophilia to be related to an increased risk of asthma.6,7 No longitudinal studies have been carried out in this respect in the Valencian Community in Spain; as a result, no objective data are available on the incidence or possible risk factors associated to asthma in school children. Likewise, the prevalence of school asthma in our Health Area is not known.

In the year 2007, La Ribera University Hospital (Alzira, Valencia) launched the RESPIR (Registro y Análisis Epidemiológico de las Sibilancias y el Asma en una Población Infantil en La Ribera [Registry and Epidemiological Analysis of Wheezing and Asthma in a Childhood Population of La Ribera]) project, which has gone through two previous phases in which the data referred to the first three years of life were analyzed.8

The aim of the present third phase of the project was to analyze the prevalence of asthma in our population at six years of age, along with the associated risk factors, and the annual and cumulative incidence of BW (bronchial wheezing) during the first six years of life.

Material and methodsA prospective longitudinal study was carried out in La Ribera University Hospital (Alzira, Valencia), following approval from the local Research Commission and Ethics Committee, as part of the RESPIR research project.

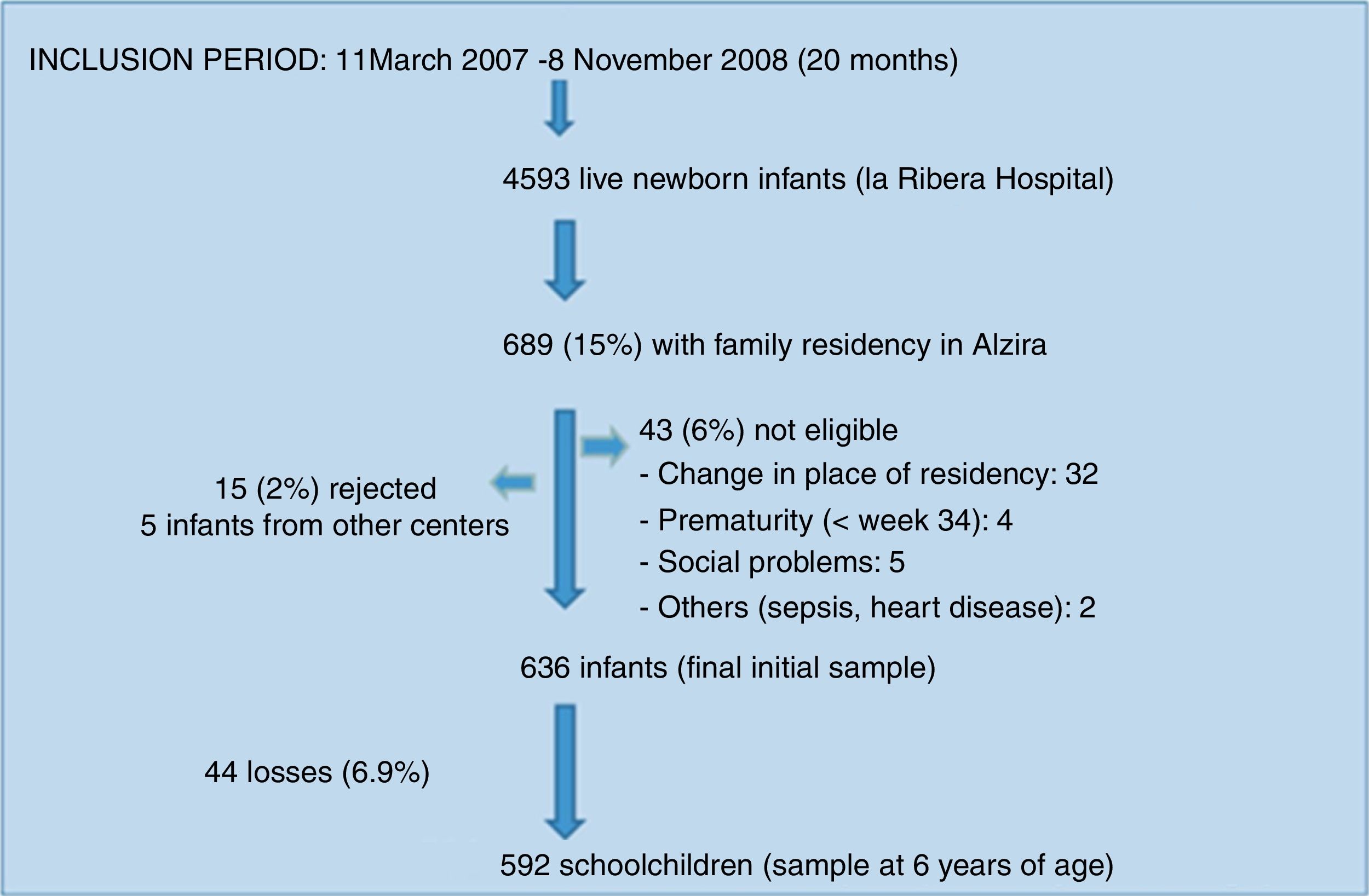

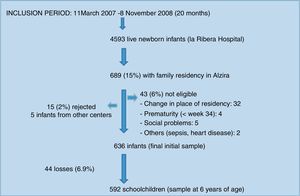

The study population consisted of a birth cohort of 636 children in the city of Alzira (Valencia), born between March 2007 and November 2008 (the period in which the required sample was compiled), and subjected to evolutive control up until six years of age. Sample size calculation and participant enrolment in the study have been described elsewhere.9

The following exclusion criteria were established: prematurity under 34 gestational weeks and/or a birth weight less than 1500g; perinatal respiratory disease requiring mechanical ventilation for more than two days; serious neurological disorders secondary to perinatal asphyxia or other causes; major malformations and/or chromosomal disorders; serious social problems; and changes in location of residency.

A review was made of the electronic primary care and hospital clinical records from birth to six years of age, and a questionnaire was sent to the family by mail at one, three and six years of age to assess previous wheezing episodes and its repercussions, as well as possible risk factors for the development of asthma (the questionnaire administered at six years of age is shown in Appendix A).

In those cases where no reply was obtained, the same questionnaire was completed by telephone. Furthermore, skin tests with conventional pneumoallergens were made in those cases where family permission was given.

Current wheezing was defined as an acute wheezing episode reported by a physician in the clinical records and/or described by the parents in the questionnaire (reference being made to “whistling sounds in the chest”). Recurrent wheezing in turn was defined as three or more wheezing episodes in the period from birth until the time of analysis. Asthma at six years of age was defined as at least one wheezing episode in the 12 months before the analysis.

Statistical analysisThe variables recorded at six years of age are indicated in Appendix B.

The descriptive data of the variables were reported as percentages, median and range. Calculation was made of the annual and cumulative incidence of wheezing during the first six years of life. A descriptive and bivariate comparative analysis was made of the study variables. Those associations found to be significant or with p < 0.2 were entered in a logistic regression analysis, with calculation of the odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95%CI) as measure of association.

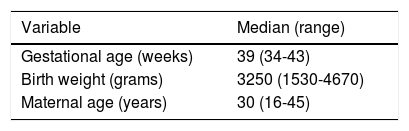

ResultsDescriptive findingsFigure 1 shows the participant enrolment process. At the time of the analysis there had been 44 losses to follow-up (6.9%). Only 24.5% of the questionnaires sent by mail were answered. The main characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants in the cohort.

| Variable | Median (range) |

|---|---|

| Gestational age (weeks) | 39 (34-43) |

| Birth weight (grams) | 3250 (1530-4670) |

| Maternal age (years) | 30 (16-45) |

| N (%) | |

| Female gender | 306 (48.1) |

| Trimester of birth | |

| January-March | 125 (19.7) |

| April-June | 157 (24.7) |

| July-September | 200 (31.4) |

| October-December | 154 (24.2) |

| Breastfeeding ≥ 3 months | 293 (47.0) |

| Twin delivery | 24 (3.8) |

| Parent educational level | |

| University | 165 (25.9) |

| Secondary | 237 (37.3) |

| Primary | 204 (32.1) |

| None | 30 (4.7) |

| Immigrant offspring | 168 (26.4) |

| Family history of asthma | |

| Total | 147 (23.2) |

| Siblings | 81 (12.7) |

| Family history of atopic disorders (rhinitis and/or atopic dermatitis) | 152 (24.0) |

| Older siblings | 286 (45.0) |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 149 (23.4) |

| Postnatal smoking exposure | |

| 0-3 years | 246 (50.3) |

| 3-6 years | 232 (45.5) |

| Domestic pets | |

| 0-3 years | 127 (25.8) |

| 3-6 years | 177 (38.1) |

| Nursing school in first 18 months | 171 (37.4) |

| Atopic dermatitis | |

| 0-3 years | 128 (21.6) |

| 3-6 years | 127 (21.5) |

| Allergy skin testing at 6 years of age | |

| Performed | 184 (31.0) |

| Positive | 50 (27.2) |

The prevalence of asthma at six years of age was 12.8% (76 cases), with a slightly greater presence in girls (13.2%) than in boys (12.3%).

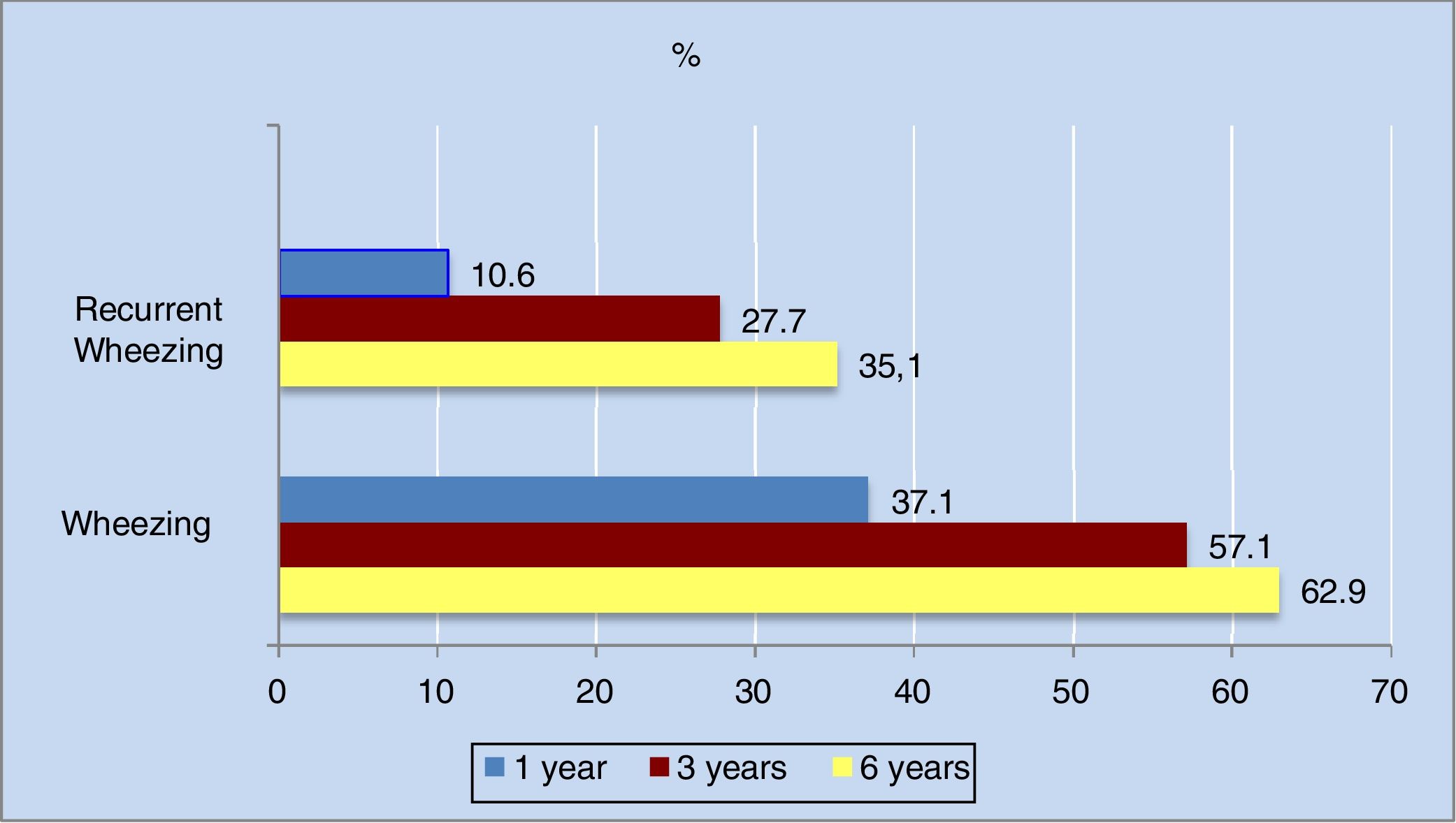

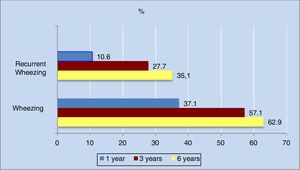

The annual incidence of wheezing decreased progressively in the different phases of the study. The decrease was most apparent in the first three years of life (from 36.3% in the first year to 16% in the third year).

As can be seen in Figure 2, the cumulative incidence of wheezing and recurrent wheezing increased considerably up until the third year of life. From three years of age onwards, the number of new cases decreased, and the cumulative incidence stabilized. Of note is the observation that 63% of the population had experienced at least one wheezing episode at six years of age, while 35% had suffered three or more episodes.

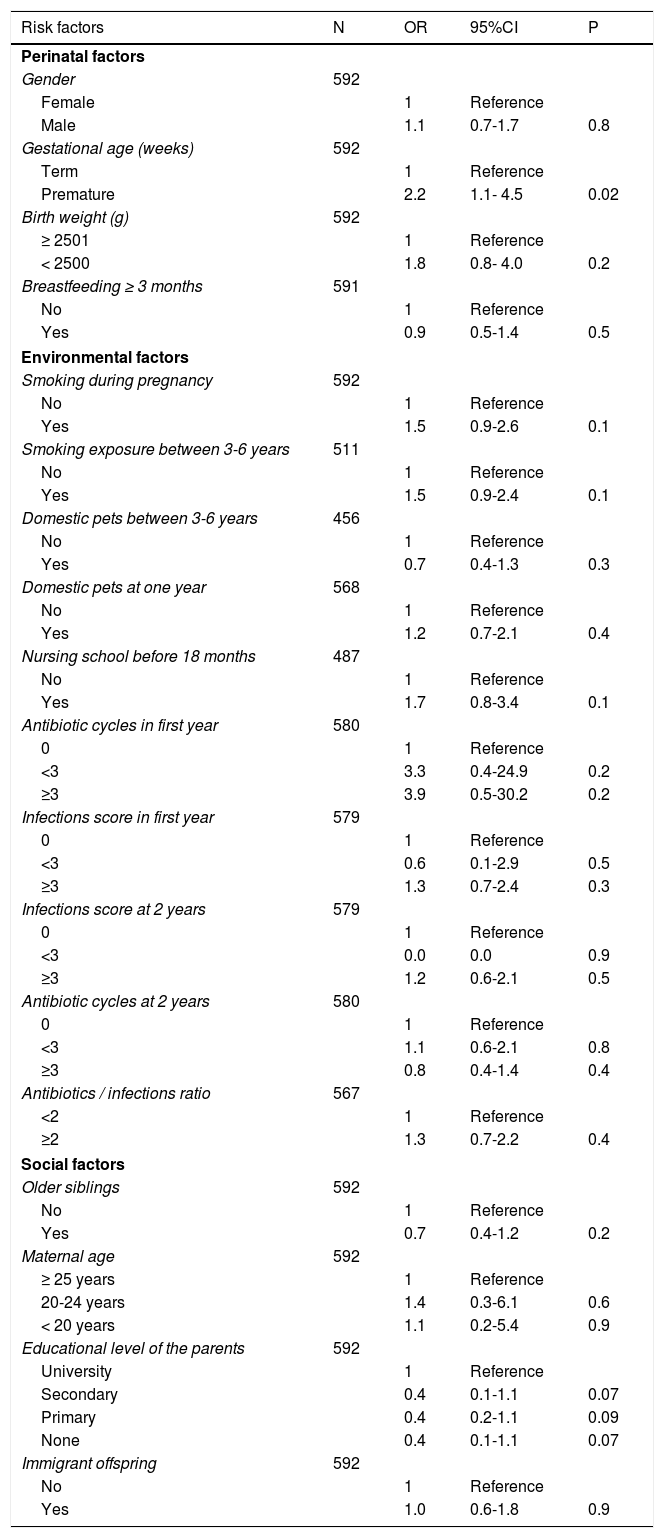

Bivariate analysisThe results of the bivariate analysis are shown in Table 2. The following variables were associated to the presence of asthma at six years of age: prematurity (OR: 2.2; 95%CI: 1.1-4.5); a family history of asthma (OR: 2.1; 95%CI: 1.1-3.8) and (separately) a history of asthma in the mother (OR: 2.1; 95%CI: 1.0-4.4); sensitization to pneumoallergens (OR: 3.3; 95%CI: 1.6-6.8); and the presence of atopic dermatitis between 3-6 years of age (OR: 2.1; 95%CI: 1.2-3.5). School asthma was also associated to the presence of at least one wheezing episode in the first year (OR: 1.8; 95%CI: 1.1-2.9), with a greater risk if the episode occurred in the first three years of life (OR: 2.9; 95%CI: 1.7-5.1). Admissions due to wheezing during the first year and third year of follow-up were associated to the development of asthma at six years of age (OR: 2.3; 95%CI: 1.0-5.3 and OR: 4.8; 95%CI: 2.4-9.9, respectively). Lastly, the presence of recurrent wheezing in the first year (Group 2), and particularly in the first three years, was associated to asthma at six years of age (OR: 2.8; 95%CI: 1.4-5.4 and OR: 5.2; 95%CI: 2.8-9.8, respectively).

Risk factors associated to the presence of asthma at 6 years of age. Bivariate analysis.

| Risk factors | N | OR | 95%CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perinatal factors | ||||

| Gender | 592 | |||

| Female | 1 | Reference | ||

| Male | 1.1 | 0.7-1.7 | 0.8 | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 592 | |||

| Term | 1 | Reference | ||

| Premature | 2.2 | 1.1- 4.5 | 0.02 | |

| Birth weight (g) | 592 | |||

| ≥ 2501 | 1 | Reference | ||

| < 2500 | 1.8 | 0.8- 4.0 | 0.2 | |

| Breastfeeding ≥ 3 months | 591 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.9 | 0.5-1.4 | 0.5 | |

| Environmental factors | ||||

| Smoking during pregnancy | 592 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.5 | 0.9-2.6 | 0.1 | |

| Smoking exposure between 3-6 years | 511 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.5 | 0.9-2.4 | 0.1 | |

| Domestic pets between 3-6 years | 456 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.7 | 0.4-1.3 | 0.3 | |

| Domestic pets at one year | 568 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.2 | 0.7-2.1 | 0.4 | |

| Nursing school before 18 months | 487 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.7 | 0.8-3.4 | 0.1 | |

| Antibiotic cycles in first year | 580 | |||

| 0 | 1 | Reference | ||

| <3 | 3.3 | 0.4-24.9 | 0.2 | |

| ≥3 | 3.9 | 0.5-30.2 | 0.2 | |

| Infections score in first year | 579 | |||

| 0 | 1 | Reference | ||

| <3 | 0.6 | 0.1-2.9 | 0.5 | |

| ≥3 | 1.3 | 0.7-2.4 | 0.3 | |

| Infections score at 2 years | 579 | |||

| 0 | 1 | Reference | ||

| <3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | |

| ≥3 | 1.2 | 0.6-2.1 | 0.5 | |

| Antibiotic cycles at 2 years | 580 | |||

| 0 | 1 | Reference | ||

| <3 | 1.1 | 0.6-2.1 | 0.8 | |

| ≥3 | 0.8 | 0.4-1.4 | 0.4 | |

| Antibiotics / infections ratio | 567 | |||

| <2 | 1 | Reference | ||

| ≥2 | 1.3 | 0.7-2.2 | 0.4 | |

| Social factors | ||||

| Older siblings | 592 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.7 | 0.4-1.2 | 0.2 | |

| Maternal age | 592 | |||

| ≥ 25 years | 1 | Reference | ||

| 20-24 years | 1.4 | 0.3-6.1 | 0.6 | |

| < 20 years | 1.1 | 0.2-5.4 | 0.9 | |

| Educational level of the parents | 592 | |||

| University | 1 | Reference | ||

| Secondary | 0.4 | 0.1-1.1 | 0.07 | |

| Primary | 0.4 | 0.2-1.1 | 0.09 | |

| None | 0.4 | 0.1-1.1 | 0.07 | |

| Immigrant offspring | 592 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.0 | 0.6-1.8 | 0.9 | |

| Risk factors | BW=bro N | OR | 95%CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family history | ||||

| Maternal asthma | 592 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.1 | 1.0-4.4 | 0.04 | |

| Siblings with asthma | 592 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.0 | 0.5-2.1 | 0.9 | |

| Paternal asthma | 592 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.8 | 0.7-4.7 | 0.2 | |

| Any relative with asthma | 592 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.1 | 1.1-3.8 | 0.02 | |

| Maternal atopic disorders | 592 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.5 | 0.8-3.1 | 0.2 | |

| Paternal atopic disorders | 592 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.4 | 0.7-2.6 | 0.3 | |

| Data on atopic disorders in child | ||||

| Sensitized (prick-test) | 183 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 3.3 | 1.6-6.8 | 0.02 | |

| Atopic dermatitis between 3-6 years | 566 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.1 | 1.2-3.5 | <0.01 | |

| Atopic dermatitis at 3 years | 584 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.5 | 0.8-2.5 | 0.2 | |

| Repercussion | ||||

| Wheezing at one year | 592 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.8 | 1.1-2.9 | <0.01 | |

| Wheezing at 3 years | 592 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.9 | 1.7-5.1 | <0.001 | |

| Group wheezing at one year | 592 | |||

| Group 0 | 1 | Reference | ||

| Group 1 | 1.4 | 0.8-2.5 | 0.2 | |

| Group 2 | 2.8 | 1.4-5.4 | <0.01 | |

| Group wheezing at 3 years | 592 | |||

| Group 0 | 1 | Reference | ||

| Group 1 | 2.1 | 1.0-4.2 | 0.04 | |

| Group 2 | 5.2 | 2.8-9.8 | <0.001 | |

| Admission at one year | 592 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.3 | 1.0-5.3 | 0.05 | |

| Admission at 3 years | 591 | |||

| No | 1 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 4.8 | 2.4-9.9 | <0.001 | |

CI: confidence interval. OR: odds ratio.

Group 0: never had wheezing.

Group1: ≤ 2 wheezing episodes.

Group 2: ≥ 3 wheezing episodes.

The number of infections and antibiotic cycles administered, and the antibiotic / infections ratio during the first two years of life were associated to the development of asthma, although in this case statistical significance was not reached (Table 2).

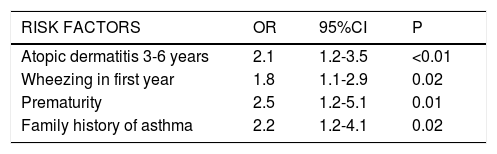

Multivariate analysisIn the final model, the following variables were significantly associated to an increased risk of asthma at six years of age: atopic dermatitis between 3-6 years of age (OR: 2.1; 95%CI: 1.2-3.5); the presence of at least one wheezing episode in the first year (OR: 1.8; 95%CI: 1.1-2.9); prematurity (OR: 2.5; 95%CI: 1.2-5.1); and a family history of asthma (OR: 2.2; 95%CI: 1.2-4.1) (Table 3).

Risk factors associated to the presence of asthma at 6 years of age. Multivariate analysis. Logistic regression model.

| RISK FACTORS | OR | 95%CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atopic dermatitis 3-6 years | 2.1 | 1.2-3.5 | <0.01 |

| Wheezing in first year | 1.8 | 1.1-2.9 | 0.02 |

| Prematurity | 2.5 | 1.2-5.1 | 0.01 |

| Family history of asthma | 2.2 | 1.2-4.1 | 0.02 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

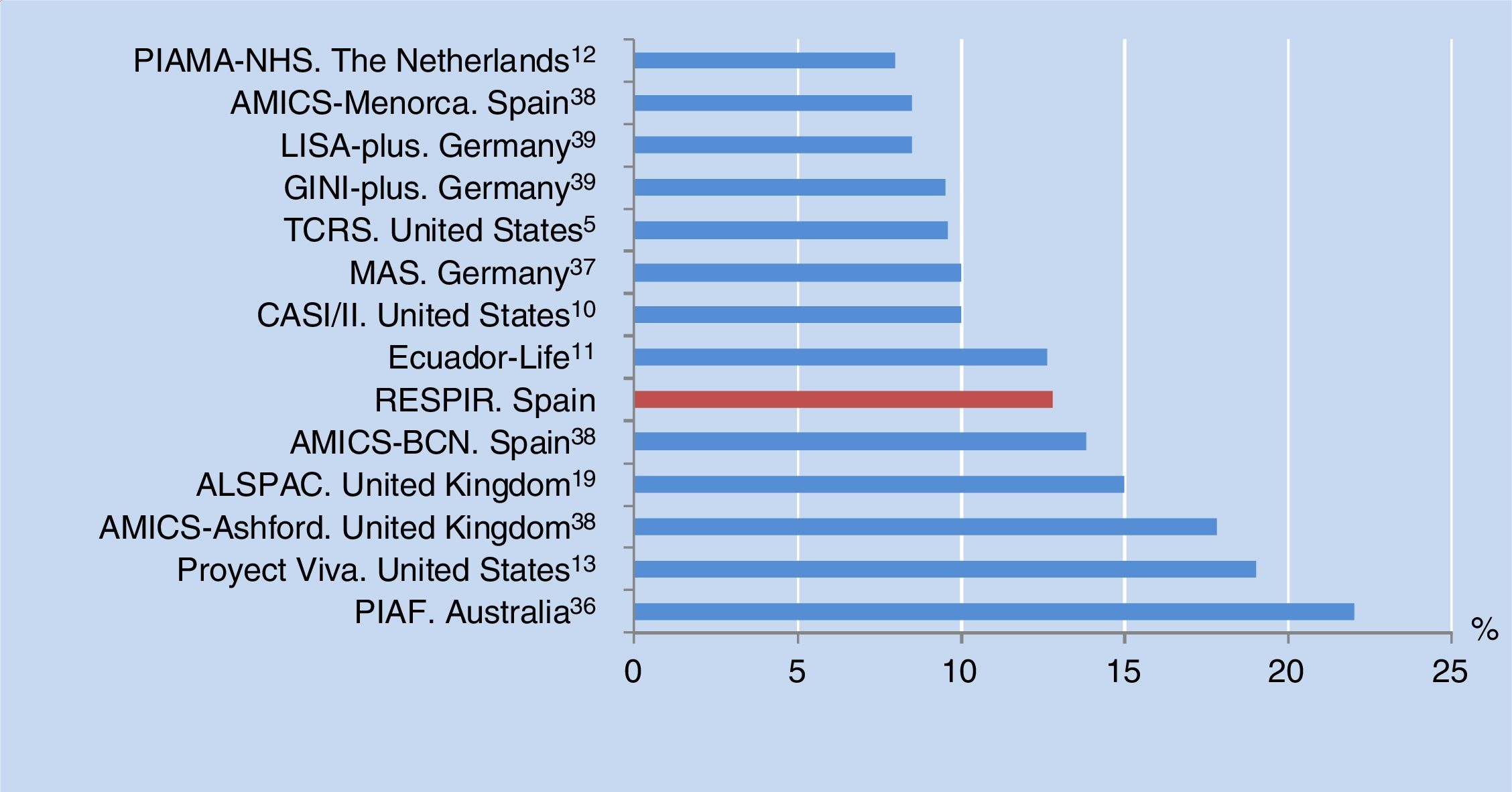

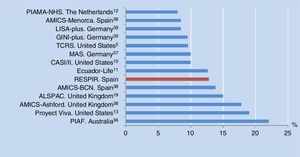

The prevalence of asthma at six years of age in the city of Alzira, Valencia, Spain is consistent with the results of other birth cohorts from different countries (median 10%, range 8-22%) (Figure 3). All of these studies used the same definition of asthma as in our own series, although in some cases adding the criterion of having been diagnosed with asthma by a physician at some time, or of having received anti-asthma medication in the previous year.10–13,38,39

The greater annual incidence of wheezing observed in the first two years reflects the large proportion of infants that experience their first episode of wheezing triggered by a viral infection in this early stage of life5. The most commonly implicated virus is respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), to which 90% of all infants under three years of age are commonly exposed. During the first infection, 25-40% of the infants suffer lower airway symptoms and wheezing.14 These patients may be more susceptible to bronchial obstruction at birth, with poorer lung function, as has been evidenced in studies of infants made before they suffer their first respiratory infection episode.15,16 From the third year onwards, with a more mature immune system and improved lung function, the number of new cases decreases considerably.5,15,17 The investigators of the AMICS-Barcelona, the British ALSPAC and the German MAS cohorts have reported the same descending trend in the annual incidence of wheezing. However, in all these studies, the incidence was lower than that observed in our population in the first year (28%, 24% and 18%, respectively).18–20

The cumulative incidence of wheezing during the six years of follow-up in our cohort was greater than that reported in other studies. In the TCRS, the percentage of cases with at least one wheezing episode during the first six years was 49%5, while that observed in the city of Valencia by the researchers of the ISAAC group was 31%.3 We have no data on the cumulative incidence of recurrent wheezing during that period in other populations with which to compare our own findings.

The greater presence of asthma seen in those children with a family history of asthma corroborates the observations of other studies5,21 and may reflect the known hereditary component of the disease, particularly in the case of atopic asthma.

In our study, physician diagnosis of atopic dermatitis was significantly correlated to an increased risk of suffering asthma at the age of six years. This is consistent with the findings of the systematic review published by Van der Hulst et al.22

Among the late preterm infants (gestational age 34-36 weeks), the likelihood of asthma was more than double that seen in infants born to term. Two retrospective cohort studies – one British and the other conducted in the United States – have corroborated this association, although its magnitude was somewhat lower than in our population (OR: 1.5; 95%CI: 1.2-1.8 and OR: 1.3; 95%CI: 1.1-1.5, respectively).23,24

It has been shown that late prematurity is characterized by an interruption in the lung development at the alveolar phase. This structural anomaly implies significantly altered lung function, with an increase in resistance and collapsibility of the airway that persists over time and increases the risk of suffering asthma in later stages of life.24–30

Due to the characteristics of our hospital center and the difficulties for posterior patient follow-up, we excluded those infants which had been born before 34 weeks of pregnancy; the risk of asthma in this group of premature infants could therefore not be determined. Other studies have found the risk of asthma in premature newborn infants to be directly proportional to the degree of prematurity.26,27

Those children that had experienced at least one wheezing episode in the first year of life showed a significantly greater risk of developing asthma at six years of age. A Swedish birth cohort recorded a greater risk of asthma among children with at least one episode of wheezing during the first two years of life than in those without wheezing (OR: 3.7; 95%CI: 2.7-5). In contrast to our study, the mentioned cohort included asthma at age eight years defined as at least four wheezing episodes in the last year, or at least one episode of wheeze during the same time period in combination with regular or occasional treatment with inhaled glucocorticosteroids.31

The bivariate analysis found the frequency of wheezing episodes in the first year to be significantly associated to the development of asthma in our population. The authors of the Swedish cohort found that those children who had experienced three or more wheezing episodes during the first two years of life presented a three-fold increase in the risk of asthma at eight years of age versus those that had suffered fewer than three episodes (OR: 3.4; 95%CI: 2.1–5.6).31 Likewise, in the TCRS cohort, the risk of school asthma among those who had suffered three or more episodes per year in the first three years of life and had a major risk factor was much greater than in those without wheezing (OR: 9.8; 95%CI: 5.6-17.2).7,32

A history of hospital admission due to wheezing during the first year and the third year of follow-up was associated to a greater presence of asthma at six years of age than in those without hospital admissions. This association would suggest that the severity of the wheezing episodes is related to their recurrence, and therefore to the presence of asthma at school age. This variable was finally not included in the multivariate analysis, due to selecting the model offering the best and most precise explanation of the associations of the variables. Most hospital admissions during the first three years are attributable to lower airway infections, mostly of a viral nature. The most widely studied viruses in this regard have been RSV and rhinovirus (RV).14,33

Other authors have also observed associations between the presence or severity of respiratory infections and the development of asthma. Sigurs et al. conducted a prospective study of 47 nursing infants requiring admission due to bronchiolitis caused by RSV during the first year of life, with the matching according to date of birth of two controls per case. The hospitalized infants were seen to have a considerably greater risk of asthma at 7.5 years of age (OR: 12.7; 95%CI: 3.4-47.1). An asthma case was defined by the presence of at least three episodes of bronchial obstruction evidenced by a physician. The difference in the definition used and the fact of selecting healthy infants as controls could explain the differences between the results of these authors and our own findings.34

A Dutch birth cohort that followed-up on 3963 children for eight years found pre-school infants under four years of age and with three or more severe infections per year to be at an increased risk of suffering asthma at 7-8 years of age (OR: 2.0; 95%CI: 1.3-3.0). The aim of the study was to establish an asthma predictive index. The authors defined an asthma case as the presence of at least one wheezing episode, a medical prescription of inhaled corticosteroids, or a physician diagnosis of asthma. Another difference with respect to our own study was that the severity of the respiratory infections was assessed from a parent survey and not from the electronic clinical records.35

It has been speculated that some individuals may be genetically susceptible to suffer more severe viral infections conferring an increased risk of asthma. In the particular case of RSV and RV, polymorphisms have been identified that would result in a deficient immune response (e.g., interferon deficit) to viral infections, with the consequent greater severity of these infections. In the early stages of life, when the immune system is still developing, the virus could damage the bronchial epithelium of genetically susceptible infants and impair its protective barrier function. Furthermore, the mucosal cells are exposed to allergens, with the facilitation of allergic sensitization by inducing immune modulator changes with atopic inflammatory activation. This in turn would result in airway alterations such as the bronchial hyperresponsiveness that characterizes persistent asthma.36,37

Our study has some limitations. Only 31% of the global cohort agreed to the allergological study; as a result, the latter was not taken into account in the multivariate analysis.

On the other hand, no lung function tests were made, due to a lack of the equipment needed to perform such tests in young children. This prevented us from evaluating the impact of lung function upon the incidence of wheezing and asthma at six years of age. Lastly, the etiology of the respiratory infections was not documented since in most cases the diagnosis of wheezing was established in the primary care setting, or was reflected in the parent questionnaires, and the study was moreover not designed for that purpose.

With regard to the strong points of the study, mention can be made of the reliability of the wheeze data source employed thanks to the easy access to the hospital and primary care electronic medical records. To the best of our knowledge, the RESPIR study is the first prospective study carried out in Spain in which the diagnosis of wheezing episodes has been contrasted against the information recorded by a physician in the patient computerized health records. On the other hand, mention must be made of the few losses recorded over the six years of follow-up (6.9%). This was again facilitated by the easy access to the patient records and insistence upon information retrieval by telephone surveys as an alternative to written questionnaires that were not completed by the parents.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of asthma at six years of age in the population of Alzira was similar to that reported in other longitudinal studies. The peak annual incidence of wheezing was recorded in the first year of life and decreased markedly thereafter. Risk factors for the development of asthma were found to be atopic dermatitis, wheezing during the first year of life, premature birth, and a family history of asthma. Full-term pregnancy and the minimization of respiratory infections at an early age could reduce the prevalence of asthma at school age in our population.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.