Several factors might affect the adherence to treatment in patients with asthma and COPD. Among these factors, the effect of religious beliefs and behaviours has been less studied so far. In this study, the effect of fasting on drug use behaviours of patients with asthma and COPD were comparatively analysed.

MethodsA total of 150 adult patients with asthma and 150 adult patients with COPD were consecutively enrolled into this cross-sectional study. The patients were asked whether they fast during Ramadan and if the answer was yes, they were kindly asked to respond to further questions related to use of inhaled medications during that particular time.

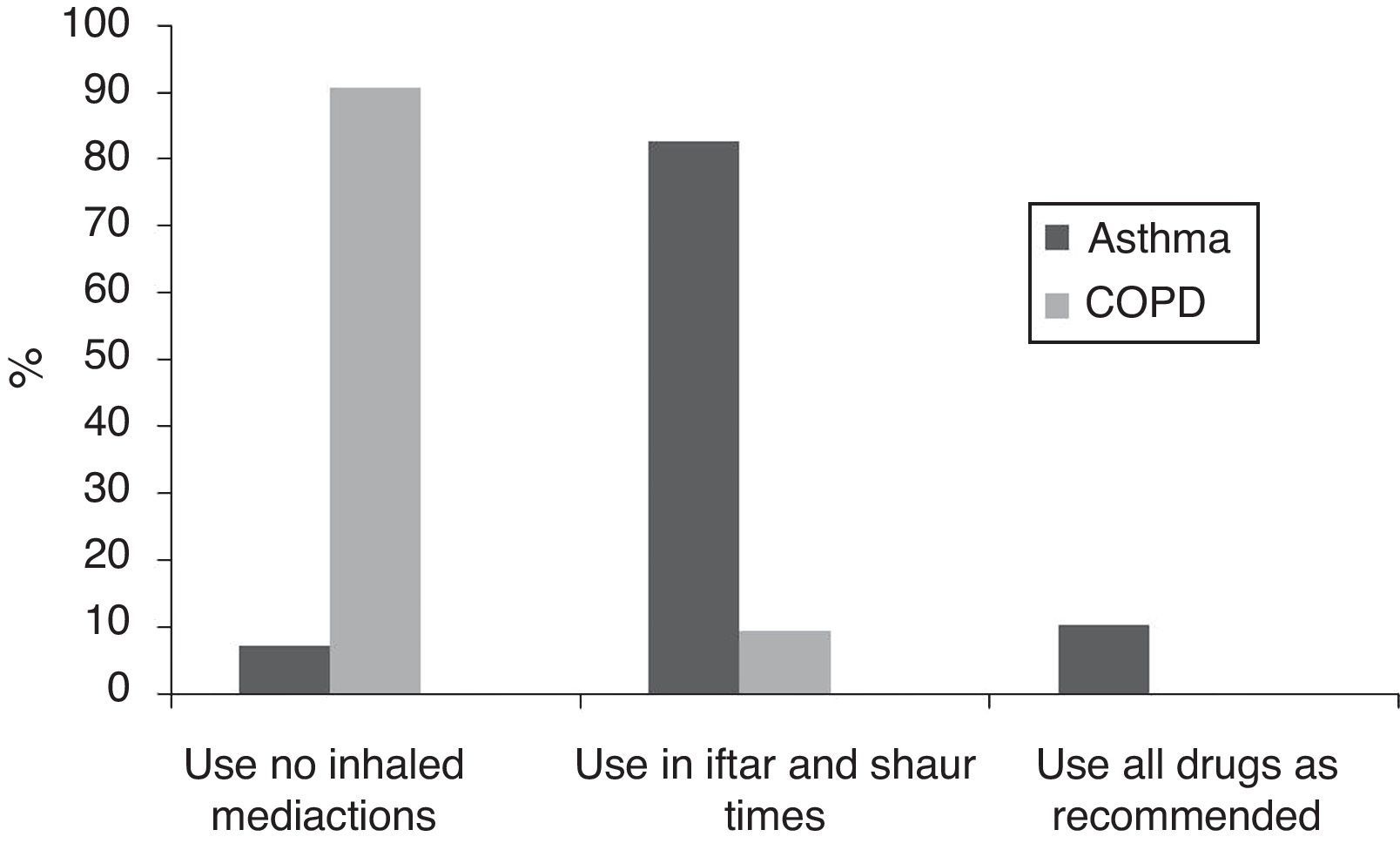

ResultsThe majority of the cases from both groups [98 (65.3%) of asthma patients and 139 (92.6%) of COPD] were fasting during Ramadan. The majority of the patients with COPD (n=126; 90.6%) reported that they quitted their regular therapy basis during Ramadan. On the other hand, the majority of asthma patients used their controller inhaled medications during Ramadan and preferred to use them on iftar and sahur times (n=81, 82.6%).

ConclusionOur results showed that in a Muslim population, the patients with asthma and COPD do not feel their diseases to be an inhibitory factor for fasting during Ramadan. However, fasting seems to be an important determining factor in medication compliance by modifying the drug use behaviours in each group in a different way. Therefore, the patients should be informed about the effects of fasting on their disease and the allowed drugs during fasting.

Chronic airway diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are among the most common respiratory diseases, affecting an estimated 300 million plus people all around the world.1,2 Asthma and COPD guidelines recommend regular use of medications for controlling symptoms, together with patient education, patient monitoring, and avoidance of risk factors.1,2 However, it has been reported that a significant number of asthma and COPD patients do not fully adhere to treatment. Drug-related factors, such as difficulties with inhaler devices, adverse effects, and cost of the treatment, are the main causes for incompliance to inhaled medications.1 Incompliance with inhaled medications may also be due to personal and social factors. Among these factors, the effect of religious beliefs and behaviours has been less studied so far in patients with obstructive pulmonary diseases.

Muslims fast at a certain time of a year, called Ramadan. During this time, healthy Muslims are expected to eat and drink nothing from sahur (before sunrise) to iftar (sunset) time. This restriction also includes medications given via oral and parenteral route. However, the drugs used via inhalation route are allowed.

Although the relation between religion and health and particularly effect of fasting on chronic diseases has been an interesting issue for physicians nearly for 25 years, this issue was only studied in a very limited number of patients with chronic airway diseases in which regular medication intake has been very important in order to gain symptom control.3 In our previous study, we demonstrated that most Muslim asthmatics did not consider asthma to be a drawback to fasting, and they continued fasting by rearranging their medication times on iftar and sahur.3 Although some overlaps might occur, asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases (COPD) differ in many aspects, patient and disease characteristics being one of them. This discrepancy might cause different disease medication use behaviours. Thus, it could be of interest to study both the infuence of fasting on drug use behaviours of patients with COPD and compare the behaviours of patients with asthma and COPD. So, in this study, we aimed to investigate the effect of fasting on drug use behaviour in patients with asthma and COPD and to see whether the patients from both diseases differ in terms of drug use during fasting.

MethodsPatient selection and the study designThe study was conducted in Allergy and Pulmonology clinics of a university hospital between 1 June 2009 and 1 June 2010. A total of 150 adult patients with asthma and 150 adult patients with COPD were consecutively enrolled into this cross-sectional study. Asthma diagnosis was based on a history of recurrent symptoms of wheezing, shortness of breath, cough, and demonstration of objective signs of reversible airway obstruction by means of at least>12% and 200ml increase in FEV1 after 15min with an inhalation of 400μg salbutamol.1 The diagnosis of COPD was defined according to the standards of GOLD guideline.2 Inclusion criteria included; 1 – A history of dyspnoea, chronic cough or sputum production, and/or a history of exposure to risk factors for the disease, especially cigarette smoking, and 2 – A FEV1/FVC ratio of less than 70%.2 Based on history, physicial findings and laboratory investigations, the cases in which asthma and COPD distinction cannot be made were not included into the study.

The investigators recorded demographics (age, gender, occupation, educational status, co-morbid diseases) and current disease activity of the patients by face-to-face interview. Current asthma activity was assessed by the Turkish version of “Asthma Control Test” (ACT).4 According to this, a score of 25 points showed completely controlled asthma, whereas 20–24 points corresponded to well-controlled asthma, with a score of less than 20 points showing uncontrolled asthma. For COPD, dyspnoea was evaluated according to the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale.5 The MRC 5-grade scale is a five-point scale based on degrees of various physical activities that precipitate dyspnoea with increasing severity from scores “0” to “5”.

The patients were then asked whether they fast during Ramadan. If the answer was “yes”, they were kindly asked to reply to further questions related to use of inhaled medications during that particular time. This questionnaire was developed by the authors on the basis of a questionnaire used in a previous study of the investigators.3 Participants were asked to give the answer which described the best of their attitude towards drug use.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of our university. All patients gave written informed consent to be included in the study.

StatisticsThe statistical analyses were performed by a computer software package (SPSS version 11.0, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics were expressed as mean±SEM and n (%). Categorical data were tested by Chi-square test. Assesment of factors associated with no inhaled medication use during Ramadan were assessed by first univariate and then multivariate logistic regression analysis. All directional p values were two-tailed and significance was assigned to values lower than 0.05.

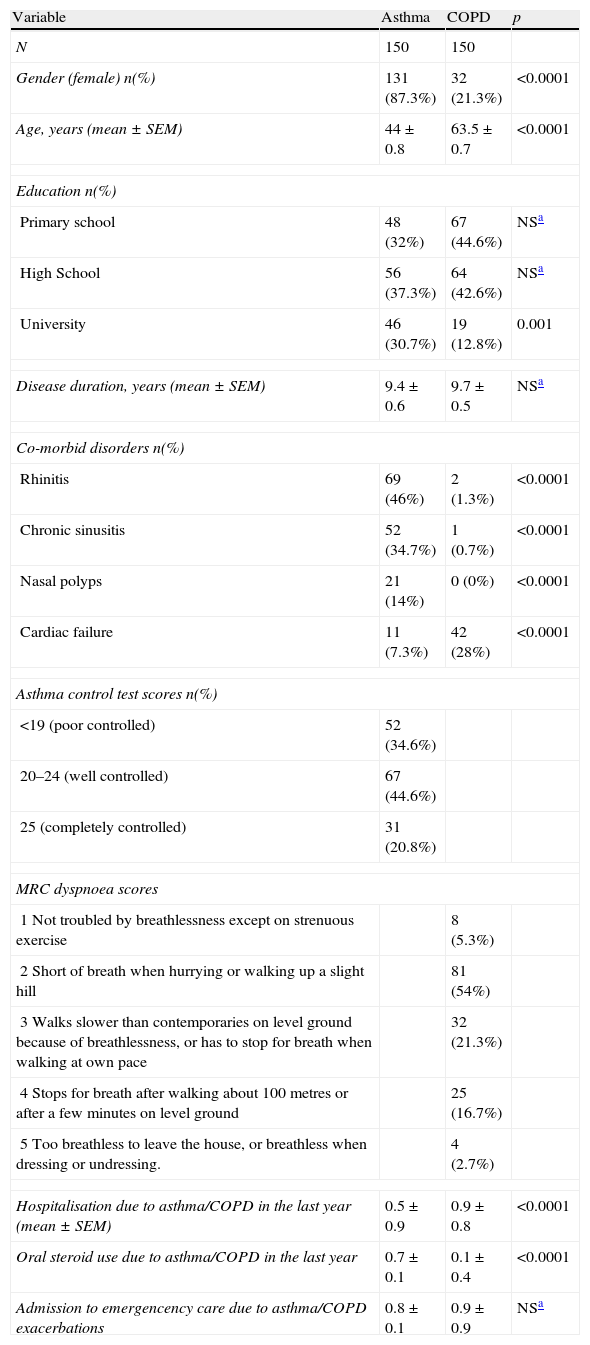

ResultsStudy groupThe study consisted of consecutively enrolled asthma (n=150) and COPD (n=150) patients. Older and male subjects dominated in COPD group in comparison to the asthma group (Table 1). In contrast, asthma patients included more female subjects with younger age. Asthma patients had a higher educational level, more rhinitis, chronic sinusitis, nasal polyps, tyroid diseases, depression, and gastric diseases as comorbid diseases (Table 1). The patients with COPD had more cardiac co-morbidities. Regarding the underlying disease activity 20.7% (n=31) of asthma patients had completely controlled asthma. The majority of the patients with COPD had a MRC score of 2 (n=81, 54.7%) (Table 1).

Demographics and disease characteristics of the study groups.

| Variable | Asthma | COPD | p |

| N | 150 | 150 | |

| Gender (female) n(%) | 131 (87.3%) | 32 (21.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Age, years (mean±SEM) | 44±0.8 | 63.5±0.7 | <0.0001 |

| Education n(%) | |||

| Primary school | 48 (32%) | 67 (44.6%) | NSa |

| High School | 56 (37.3%) | 64 (42.6%) | NSa |

| University | 46 (30.7%) | 19 (12.8%) | 0.001 |

| Disease duration, years (mean±SEM) | 9.4±0.6 | 9.7±0.5 | NSa |

| Co-morbid disorders n(%) | |||

| Rhinitis | 69 (46%) | 2 (1.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic sinusitis | 52 (34.7%) | 1 (0.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Nasal polyps | 21 (14%) | 0 (0%) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac failure | 11 (7.3%) | 42 (28%) | <0.0001 |

| Asthma control test scores n(%) | |||

| <19 (poor controlled) | 52 (34.6%) | ||

| 20–24 (well controlled) | 67 (44.6%) | ||

| 25 (completely controlled) | 31 (20.8%) | ||

| MRC dyspnoea scores | |||

| 1 Not troubled by breathlessness except on strenuous exercise | 8 (5.3%) | ||

| 2 Short of breath when hurrying or walking up a slight hill | 81 (54%) | ||

| 3 Walks slower than contemporaries on level ground because of breathlessness, or has to stop for breath when walking at own pace | 32 (21.3%) | ||

| 4 Stops for breath after walking about 100 metres or after a few minutes on level ground | 25 (16.7%) | ||

| 5 Too breathless to leave the house, or breathless when dressing or undressing. | 4 (2.7%) | ||

| Hospitalisation due to asthma/COPD in the last year (mean±SEM) | 0.5±0.9 | 0.9±0.8 | <0.0001 |

| Oral steroid use due to asthma/COPD in the last year | 0.7±0.1 | 0.1±0.4 | <0.0001 |

| Admission to emergencency care due to asthma/COPD exacerbations | 0.8±0.1 | 0.9±0.9 | NSa |

The majority of the cases from both groups [98 (65.3%) of asthma patients and 139 (92.6%) of COPD] reported that they were fasting during Ramadan. The percentage of the fasting patients was similar in each ACT or MRC category. Previous attacks or hospitalisations due to underlying asthma/COPD also did not influence the fasting rates.

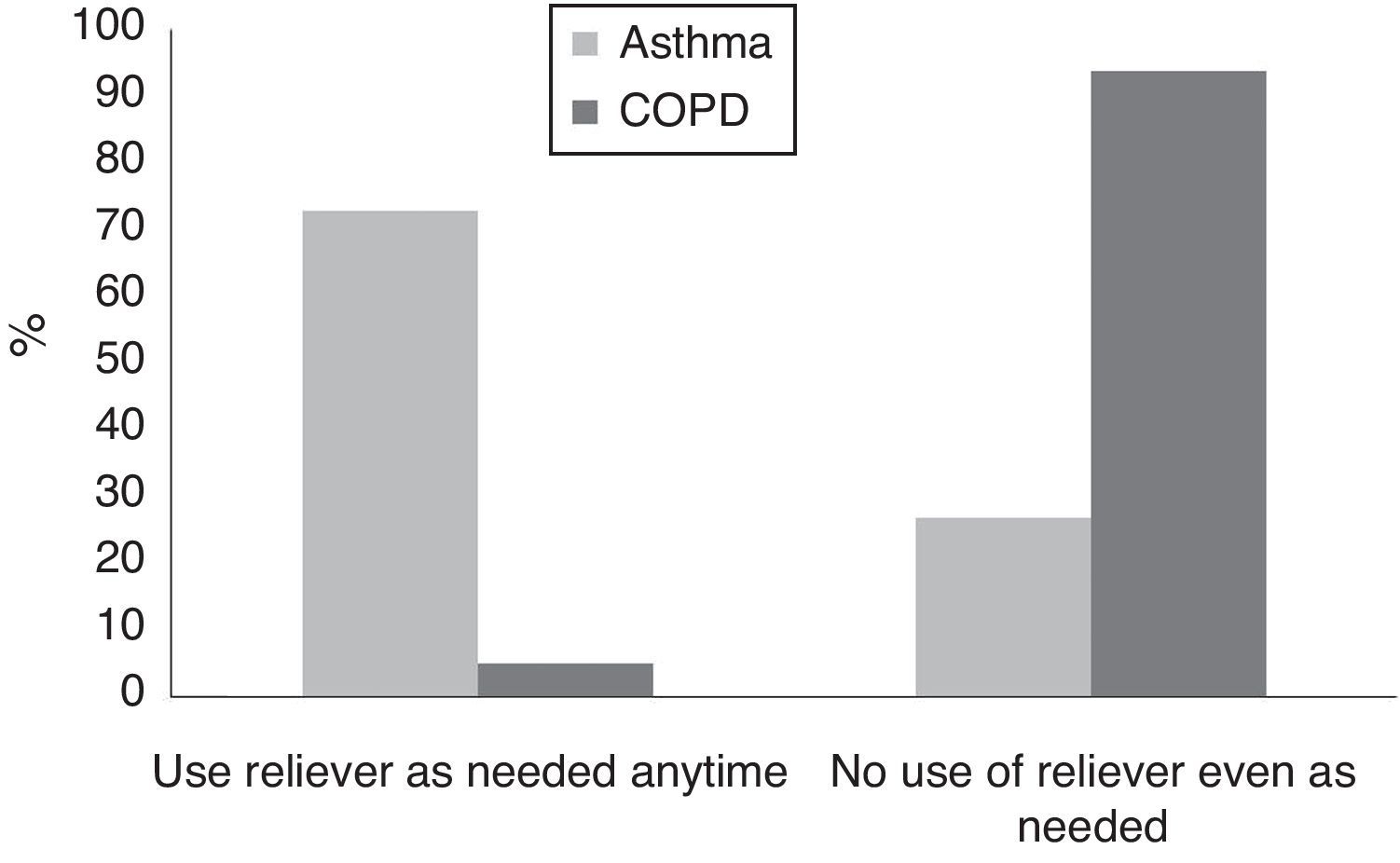

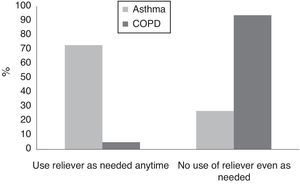

Considering their inhaled medication use during Ramadan, both groups had different attitudes. The majority of the patients with COPD (n=126; 90.6%) reported that they quitted their therapy which they were expected to use on a regular basis during Ramadan (Fig. 1). On the other hand, the majority of asthma patients used their controller inhaled medications during Ramadan and preferred to use them on iftar and sahur times (n=81, 82.6%) (Fig. 1). When the patients were asked about their attitudes towards using rescue medications if their symptoms exacerbate during Ramadan, the behaviours were again different in both groups (p<0.001) (Fig. 2). While the majority of the patients with asthma reported to use these medications (57.73%) when needed any time during Ramadan, only eight out of 141 (5.6%) patients with COPD used their symptom relievers without any modification during this particular time (Fig. 2). When compared according to ACT and MRC scores, there was no significant difference between the two groups of the patients in terms of attitudes against maintenance and reliever medication usage during fasting (p>0.05). Previous attacks, or hospitalisations also did not influence drug use during Ramadan.

DiscussionOur results showed that in a Muslim population, the patients with asthma and COPD do not feel their diseases to be an inhibitory factor for fasting during Ramadan. However, fasting seems to be an important determining factor in medication compliance by modifying the drug use behaviours in each group in a different way.

The month of Ramadan is the nineth month of the lunar calender. Fasting includes neither eating nor drinking during the day.6,7 The patients with chronic illness are allowed not to fast during Ramadan because of ongoing disease conditions. However, despite this fact, some patients fast if they feel that they can do. Suggesting this, in our group, considering the high rate of fasting patients during Ramadan, having COPD and asthma diagnosis did not inhibit the patients fasting attitude.

The oral medications, injections, ear and nose drops and suppositories are not allowed for those fasting. Use of eye drops and inhalers are accepted as a process that does not nullify the fast.8 Despite this information, a considerable proportion of patients with chronic illness change their medication regimens during fasting without asking their physician.7 In a questionnaire-based study on 80 Muslim patients, compliance to eye drop medication during fasting was assessed and the majority of the patients thought that eye drops nullify the fast. This resulted in reduced patient compliance.9 In another survey, only 42% of the patients were found to adhere to their usual treatment, while the remaining patients either stopped or changed their drug intake pattern while fasting during Ramadan.10,11 In our study group, each group exhibited a different pattern for drug use during this particular time. The majority of the patients with asthma prefered not to stop their regular maintenance drugs, instead they used them in a different way like using in sahur and iftar times. In contrast, the majority of the COPD patients quitted using these medications during Ramadan.

Adjustment of the drug doses seems to be a way of using medications for fasting patients.12,13 “Sahur” is a time just before the sunrise when people start to fast whereas “iftar” (sun down) is the time when they are allowed to eat and drink until the next “sahur” time. Therefore, the most common adjustments are taking a single daily dose and two in allowed eating times.12 In accordance with previous trials, our results suggested a change in drug use behaviours of the patients with asthma, although inhaled medications are certainly allowed during fasting. Previous studies showed that asthma patients wanted to be involved in the management of treatment actively by adjusting their controller maintanence medications depending on changes in their symptoms.14 Fasting seems to be another factor in which asthma patients are willing to be involved actively in the management of treatment as the majority of these patients adjusted to use their controller inhaled medications in “sahur” and “iftar” times during the month of Ramadan. The patients might feel more confident when they use the drugs in iftar and sahur times despite the knowledge that these drugs are allowed during fasting. This approach seems to be reasonable when compared to the hazardous alternative of quitting all the drugs. However, it is of interest whether the efficacy of the drugs differs when they are used in this way. In the traditional approach, inhaled steroids other than ciclesonid and mometasone are recommended twice daily with 12h apart. The interval between the “iftar” and “sahur” differs according to the season of Ramadan month corresponded. It is longer than 12h during summer months whereas a shorter period for fasting is available during winter months. Based on data about pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of inhaled steroids, this type of recommendations is not expected to have a change in efficacy of inhaled steroids in asthma. Other maintenance treatment options of anti-leukotriens or theophyllines are available in the form of once daily use which allows them to be used confidently in fasting. A recent study recommended to use a long acting formulation of teophylline taken once daily in order to reduce side-effects in asthmatic patients during Ramadan.12 Taken together, all inhaled asthma medications used in iftar and sahur times are not expected to decrease the efficacy of the drugs and this way seems to be acceptable for patients who do not want to use their drugs during fasting hours.

Although the reason why the majority of COPD patients quit their inhaled medications during Ramadan cannot be extracted from this data, it is certain that the patients with asthma and COPD should be particularly informed and convinced that inhaler drugs are already allowed to use during fasting. But despite this fact, it seems that the patients feel more comfortable while using their drugs in this way. We believe that the use of controller treatment in “iftar” and “sahur” times of the Ramadan month allow subjects to use their medications without any interruption of the treatment. Actually, considering the fact that quitting the medications during fasting can cause much more harmful effects on disease activity, this advice seems to be a reasonable approach for better disease control. However, evaluation of the effect of this approach on disease activity such as disease control can provide a better rationale for recommendation of this approach to the patients.

The behavioural difference between asthma and COPD patients emphasizes the necessity of a special approach to COPD patients in terms of fasting as COPD patients might be more vulnarable to exacerbations because of quitting their medications.

This study provides other important data. Underlying disease activity did not seem to affect the fasting behaviours of the patients with asthma or COPD. Although we do not have the data referring to how their asthma/COPD progressed during Ramadan month, this item is important as it indicates that subjects with asthma or COPD are willing to fast regardless of activity of the illness. Actually, the patients with COPD were more willingly to fast during Ramadan compared to asthmatics. Moreover, they had a tendency to have more strict individual rules related to drug use while fasting despite more severe underlying conditions. They preferred not to use not only the drugs recommended on a regular basis but also rescue medications. This behaviour was not so evident in patients with asthma. Discrepancy in demographic features of the groups might, at least, partly explain this. The patients in COPD were mostly male cases with advanced age. In general, older people are more prone to behave traditionally. However, it would be interesting to see the disease activity during Ramadan; this was beyond the aim of this study but requires further evaluation.

In conclusion, it is recommended for the physicians to take and document a spiritual history in the medical record of the patients.15 The physicians can use this information for helping the patients to cope with their disease. When fasting is taken into consideration as a religious issue, learning the attitudes of the patients about fasting could also be useful for physicians while treating chronic respiratory illnesses. The patients should be informed about the effects of fasting on their disease and the allowed drugs during fasting. The results of our study reinforce the importance of remembering a patient's religious beliefs as a part of medical care. We think that physicians should inform their patients how to fast without endangering their health.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human subjects and animals in researchProtection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Patients’ data protectionConfidentiality of Data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentRight to privacy and informed consent. The authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestNone of the authors have a conflict of interest and any kind of financial or editorial support.

ContributionsThe authors made the following contributions to the study:

Ömür Aydin: Study design, inclusion of asthma patients, data entrance, writing manuscript.

Gülfem Çelik: Study design, inclusion of asthma patients, statistical analysis, writing manuscript.

Zeynep Pınar Önen: Study design, inclusion of COPD patients, significant contribution to written manuscript.

İnsu Yilmaz: Study design, inclusion of asthma patients, significant contribution to written manuscript.

Seçil Kepil Özdemir: Study design, inclusion of asthma patients, significant contribution to written manuscript.

Öznur Yildiz: Study design, inclusion of COPD patients, significant contribution to written manuscript.

Dilşad Mungan: Study design, inclusion of asthma patients, significant contribution to written manuscript.

Yavuz Selim Demirel: Study design, inclusion of asthma patients, significant contribution to written manuscript.