Asthma is the most common chronic disease in childhood. Hospital admissions in the child population appear to be reducing in different populations.

MethodsWe have retrospectively analysed admissions into hospitals in our region due to asthma in a 0 to 14 years population, between the years 1995 and 2007. The age, sex, date of admission, and length of hospital stay of each patient was recorded and analysed.

ResultsA total of 9106 admissions (64% males) have been included. A gradual trend towards a reduction in admissions is observed during the period analysed. There were more admissions in 1996, with 2.91 per thousand inhabitants, gradually reducing to 1.33 per thousand in 2007. There were more admissions in May and between September and December, being less frequent in July and August. The mean stay in this period was 4.18 days, which was stable during the whole period of the study. Older children tended to have a longer hospital stay.

ConclusionsOur study shows that admissions due to childhood asthma tend to be decreasing, particularly due to younger males, with no change in the length of hospital stay. Asthma exacerbations seemed to be associated with infections and exposure to allergens.

Asthma is the most common chronic disease in childhood, with large differences in prevalence as well as in other epidemiological aspects among different populations.1

In the last few years the prevalence of the disease appears to be stabilising in the adolescent population, although it is still increasing in the child population.2

Hospital admissions take up a significant part of the health spending on the disease, in addition to the effects on the quality of life of the patients and their families, which is especially important in the childhood population.3 There seems to have been a decreasing trend in hospital admissions due to childhood asthma in the past few years, although its magnitude and time sequence differ between geographical areas.4–7

The aim of our study was to evaluate the progression of hospital admissions due to asthma over the past 13 years in the north-west of Spain.

Material and methodsWe have retrospectively analysed all admissions due to asthma in all the Galician (Spain) Public Health Service Hospitals, between the years 1995 and 2007. All patients with asthma as the primary or secondary diagnosis (provided by the Clinic Records Department, according to ICD-9 classification) were included. The age, sex, date of admission and length of hospital stay of each patient was recorded and analysed.

There were 315,825 children (51.4% males) between 0 and 14 years of age in our Autonomous Community according to the 2003 population census.8 Around 98% of these have public health service cover, leaving a small percentage excluded with private health cover.

Statistical analysisThe normality of the distributions was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For the two category comparison of continuous variables, the Student t test was used when they had a normal distribution and the Mann Whitney U test when they had a non-parametric distribution. For the comparison of continuous variables of more than two categories we used ANOVA in variables with a normal distribution and the Kruskal Wallis test when they did not show a normal distribution. The categorical variables comparison was performed using the Chi-squared test.

All the analyses were performed using the SPSS 15 statistics program.

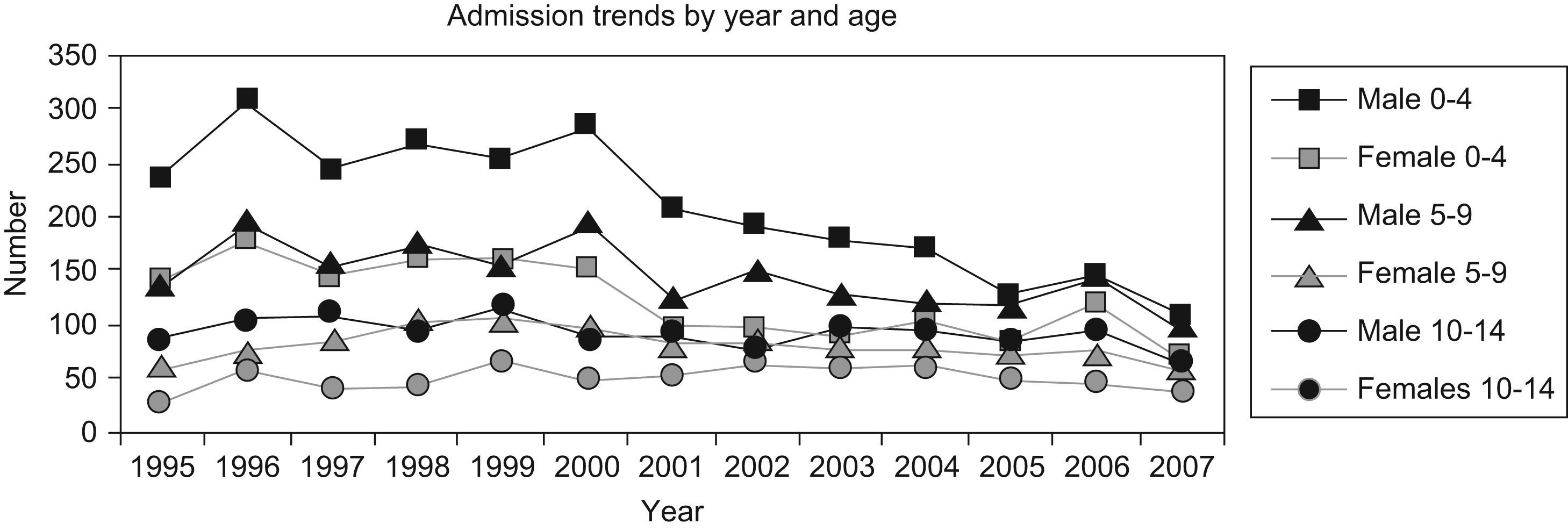

ResultsThere were 9106 hospital admissions with asthma as the primary or secondary diagnosis in the 13 years analysed; with a predominance of males (64% of the total admissions), and 47% were under 4 years (Table 1; Figure 1).

Hospital admissions and long hospital stay by sex and age group

| Admissions, number | Admissions, by age | ||||||

| Male, n (%) | Female, n (%) | p | Total N (rate) | 0–4 years old n (%) | 5–9 years old n (%) | 10–14 years old n (%) | |

| 1995 | 461 (67) | 228 (33) | 0.000 | 689 (2.18) | 375 (54) | 197 (29) | 117 (17) |

| 1996 | 606 (66) | 312 (34) | 0.000 | 918 (2.91) | 488 (53) | 268 (29) | 162 (18) |

| 1997 | 506 (65) | 269 (35) | 0.000 | 775 (2.45) | 387 (50) | 236 (30) | 152 (20) |

| 1998 | 541 (64) | 304 (36) | 0.000 | 845 (2.68) | 428 (51) | 280 (33) | 137 (16) |

| 1999 | 527 (61) | 335 (39) | 0.000 | 862 (2.73) | 411 (48) | 264 (30) | 187 (22) |

| 2000 | 570 (66) | 292 (34) | 0.000 | 862 (2.73) | 437 (51) | 287 (33) | 138 (16) |

| 2001 | 421 (65) | 230 (35) | 0.000 | 651 (2.06) | 302 (47) | 204 (31) | 145 (22) |

| 2002 | 421 (62.5) | 253 (37.5) | 0.000 | 674 (2.13) | 289 (43) | 244 (36) | 141 (21) |

| 2003 | 399 (63.5) | 229 (37.5) | 0.000 | 628 (1.99) | 271 (43) | 203 (32) | 154 (25) |

| 2004 | 384 (61) | 247 (39) | 0.000 | 631 (2.00) | 274 (43) | 200 (32) | 157 (25) |

| 2005 | 328 (62) | 203 (38) | 0.000 | 531 (1.68) | 208 (39) | 190 (36) | 133 (25) |

| 2006 | 382 (61.5) | 239 (38.5) | 0.000 | 621 (1.97) | 265 (43) | 220 (35) | 136 (22) |

| 2007 | 255 (61) | 164 (39) | 0.000 | 419 (1.33) | 170 (41) | 146 (25) | 103 (24) |

| Total admissions | 5801 (64) | 3305 (36) | 4305 (47) | 2939 (32) | 1862 (21) | ||

| Mean hospital stay | 4.09 | 4.35 | 0.086 | 4.24 | 3.89 | 4.51 | |

Mean hospital stay in days.

Difference between 5–9 years old and 10–14 years old. p=0.012

Rate: per 1000 inhabitants between 0–14 years of age.

A decreasing trend in the number of hospital admissions due to asthma was observed during the period studied, particularly in younger males (Figure 1). The highest number of admissions was seen in 1996, with 2.91 per thousand inhabitants, gradually falling to 1.33 per thousand in 2007 (Table 1).

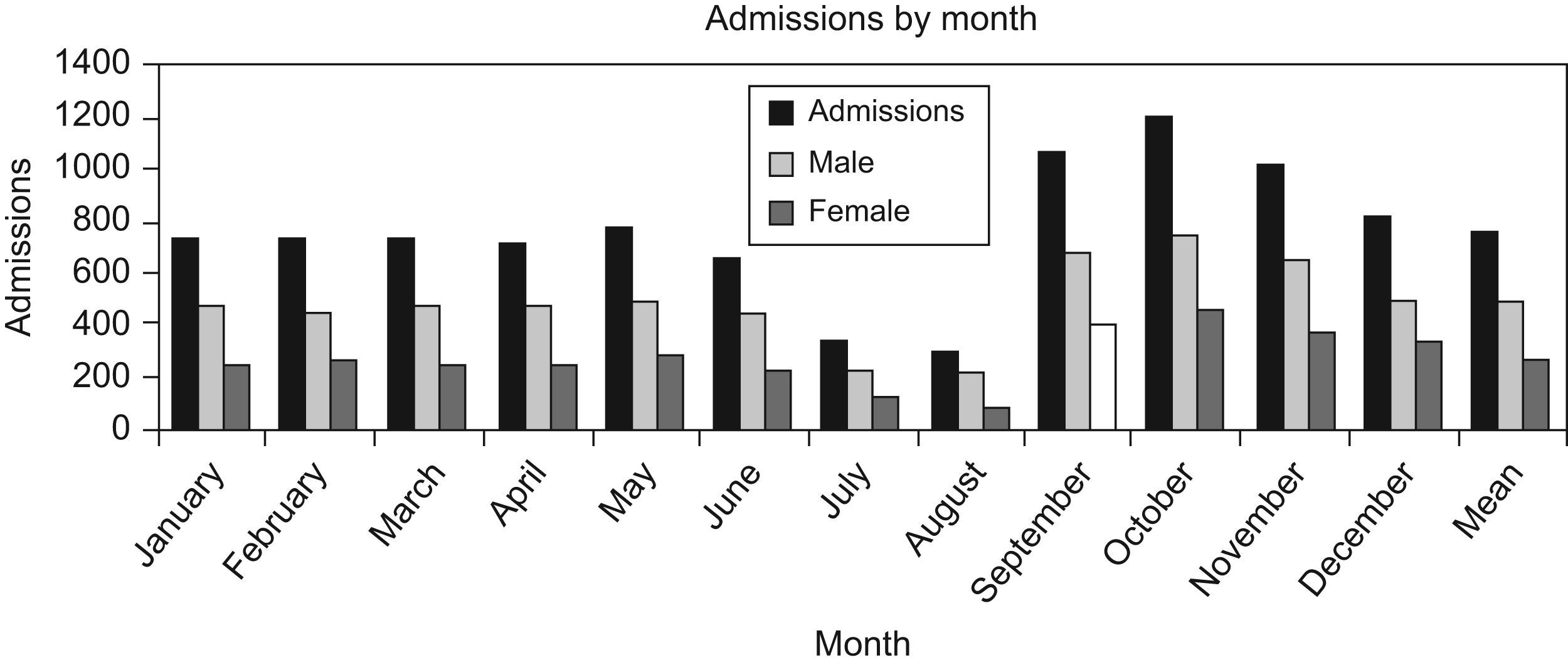

There were more admissions in May, and between September and December, with July and August having the least. The number of admissions in October was four times that of August (Figure 2).

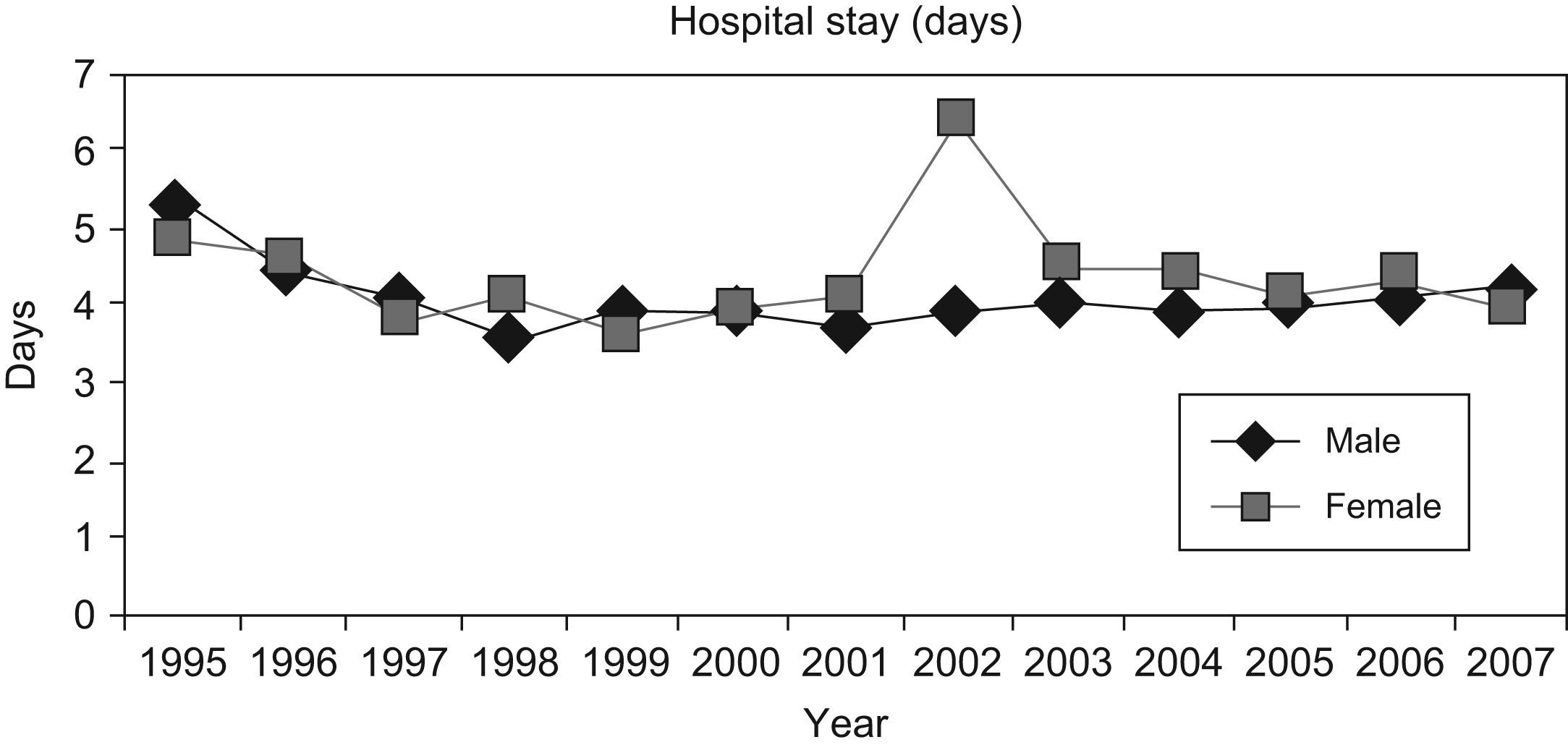

The mean stay for the period was 4.18 days and a median of 3 days, with no differences between sexes. Older boys had a longer hospital stay (4.51 days), significantly higher than that of the 5–9 year old group. There were no differences between the hospital stay in boys less than 4 years old and the other boys (Figure 3).

The mean stay remained stable throughout the whole period (Figure 3). The increase in girls in the year 2002 was due to one case with a very long hospital stay.

DiscussionThe principal finding in our study was the gradual reduction, over the period studied, in the number of hospital admissions due to asthma, especially in boys under 4 years; similar to that described in other populations.4–7

The rate of hospital admissions per inhabitant is lower than that reported for other child populations of these ages.4,5

The decrease in hospital admissions, despite the increase in prevalence of the disease in this population group,2 is probably due to the influence of various factors. On the one hand, it could be a reflection of a decrease in the incidence of infectious diseases, which are the primary cause of acute exacerbation of asthma.9,10 This fact could be based on, at least in part, the improvement of vaccination coverage among children.11 Other factors that may contribute to this reduction in hospital admissions could be better management of the diseases or better access to health care, since it is well known that better management of the diseases leads to a reduction in morbidity and costs.7,12 It has been shown that in recent years, the use of inhaled corticosteroids by asthma patients has increased by 4 or 5 times.13,14 This overall improvement in health care also appears to be deduced from the increase in the prevalence of asthma associated with a reduction in the hospital admissions rate.

The admissions peak in May could be associated with pollen levels, since it is known that pollen has an influence on asthma exacerbations9,15; and that 18% of our childhood asthma population have shown sensitivity to pollen.16 In our geographic area, the highest pollen levels are recorded in April and May, mainly related to grasses (gramineae).17

These increases in spring are observed in some populations,18,19 but not in others,20,21 which seems to reinforce the relationship with specific environmental factors of our community.

The autumn peak is more common in the literature than the spring one.19–23 Exacerbations in this period have been associated with various causes. On the one hand, it has been associated with lower therapeutic compliance at the end of the holiday period.24 On the other hand, in our country infection peaks due to viruses occur in autumn,25 helped along by virus transmission between children with the restarting of the school year.19,24 Moreover, as the weather becomes cooler the people spend more time in the home.21 Thus, this closer contact helps virus transmission19; and exposure to environmental irritants may be higher, such as the known negative effect of passive smoking on lung function in children.26

The predominance of males among the children admitted is in agreement with that found in other studies,4,5,27 and with the higher prevalence of asthma in the male child population in our community.28

The mean hospital stay was 4.2 days, and this was stable during the period analysed. This is higher than that reported in other European countries, where it is less than 3 days.4,29 The management of the disease is probably different between populations. The relationship between a lower admission rate and a longer mean hospital stay could be due to the use of more restrictive criteria to decide on hospital admission, so that less severe exacerbations in other populations are admitted to hospital.27,30

In conclusion, hospital admissions due to childhood asthma in our population are decreasing, particularly in the younger males, with no changes in the length of hospital stay. Given the time sequence, asthma exacerbations appear to be associated with infections and exposure to allergens.