Azzalini L, Ferrer E, Ramalho LN, Moreno M, Domínguez M, Colmenero J, Peinado VI, et al. Cigarette Smoking Exacerbates Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Obese Rats. Hepatology 2010; 51: 1567-1576.

CommentIn the article we will comment today, Azzalini et al.1 provide a novel evidence suggesting that cigarette smoking (CS) causes oxidative stress and worsens the severity of non alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in an experimental model of Zucker obese rats. Smoker rats were exposed to 2 cigarettes/day, 5 days/week for 4 weeks. As expected, obese rats showed hypercholesterolemia, insulin resistance and histological features of NAFLD. Smoking did not modify the lipidic or glucidic serum profiles. Smoking increased alanine amonitrasferase (ALT) serum levels and the degree of liver injury in obese rats, whereas it only induced minor changes in control rats.

The authors explain the possible mechanism involved in the deleterious effect of CS through the increase of oxidative stress and hepatocellular apoptosis in obese rats, but not in controls and therefore this explains the increment in the histological severity of NAFLD. Smoking increased the hepatic expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 and procollagen-alpha2 in obese but not in control rats. Finally, smoking regulated extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) and AKT phosporylation. It is important to mention that the deleterious effects of CS were not observed after a short exposure, therefore longer or chronic exposures (as it happens with smokers) are necessary to induce the liver damage.

Even we need further studies to assess whether this experimental findings also occurs in humans with obesity and NAFLD, as well as better delineate the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved, this is a very interesting study that links three important public health problems: smoking, obesity and NAFLD.

Precisely, those three problems are the 21st century health challenges in many developing countries and Mexico is a good example. In this comment we will address the main features of those diseases and their association.

Cigarette smoking is an increasing public health problem in Mexico, where there is a growing group of young population beginning to smoke at early ages, even before adolescence.2 In Mexico tobacco smoking prevalence is about 20.4%, among those aged 12 to 65 (29.9% for males and 11.8% for females) which represents nearly 17 million of smokers.3

Smoking rates for adolescents are alarming high, ranging from 13% to 28% in 2006. The Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) found that between 8 to 15% of students have tried cigarettes before the age of 13.4 Estimates of premature mortality attributable to smoking show that tobacco consumption is responsible for 25,000 to 60,000 deaths each year in Mexico.5 Further, nearly 11 million Mexicans who have never smoked (25% of men and 22% of women) are exposed to secondhand smoke.3 The total healthcare expenditures associated with smoking in Mexico were estimated to be 75.2 billion pesos (US 5.7 billion) in 2008.6

Even there is misperception of the main consequences of smoking are located in the respiratory tract, most smokers die as a consequence of an increased risk of atherothrombotic clinical events such as myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular events.2

On the other hand, in our country several studies have documented a high prevalence of overweigh and obesity.7,8 Currently Mexico ranks first worldwide in childhood obesity and second in morbid obesity (70% of adults and 30% of children suffer it) for which Mexican government is spending more than 40,000 million pesos per year for health problems caused by this decease, equivalent to 33% of federal spending on direct health services. It is estimated that the figure could reach 77,919 million pesos in 2017.9

What about the third problem? Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a common clinical condition with histological features that resemble those of alcohol-induced liver injury, but occur in patients who do not abuse alcohol. This is an increasingly recognized cause of chronic liver disease (CLD), representing the leading cause of hepatology referral in some centers.10,11

NAFLD is emerging as the most common chronic liver disease in Western countries and also in other parts of the world. NAFLD encompasses a histological spectrum ranging from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis, advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. The problem of NAFLD is not confined to its potential to cause serious liver related morbidity and mortality. It frequently occurs with features of the metabolic syndrome including obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and hypertension. Moreover, it has been found to be a novel predictor to cardiovascular disease.11

The global increase in the prevalence of obesity has heralded a rise in associated NAFLD and, although high quality data is currently lacking, the condition is clearly increasing in children also. Obesity is the most important risk factor associated with nafld, which is caused by to impaired insulin activity, overflow of portal triglycerides, and production of inflammatory cytokines; all of these are deleterious to hepatocytes. These phenomena facilitate disruptions in hepatic physiology, as observed in alcoholic hepatitis; however, consumption of this substance is absent. NAFLD has had a great impact due to the fact that previously, main cases of cryptogenic cirrhosis actually were attributed to this disease. Despite advances in understanding the pathophysiologic process of the disease, there is no better treatment than weight reduction (a combination of diet and exercise.12,13

How we link the three problems? Even there is no discussion about the benefits to stop, weight gain is a likely outcome of smoking cessation.14 Although the probability and extent of weight gain may be associated with age, body composition, the number of cigarettes smok ed per day, etc, the general public tends to believe that weight gain is inevitable. As such, fear of weight gain is often reported as a strong disincentive to stop smoking and actual weight gain is often cited as a primary cause for returning to smoking after successfully quitting.15,16

When smokers quit, on average gain from 5 to 6 kg, although approximately 10% gain more than 10 kg. The importance of smoking cessation as a contributing cause of the current obesity epidemic has been little studied. In the USA, the rate of obesity attributable to smoking cessation has been estimated at approximately 6.0% and 3.2% for males and females, respectively.16 In Mexico we lack this information but many smokers show overweight, therefore a small increase could take them to higher BMI and obesity.

Another link between smoking, obesity and NAFLD is leptin. Leptin acts as a satiety signal, regulates appetite and energy expenditure. Leptin may contribute to the inverse relationship between cigarette smoking and body weight, also it may contribute to increase hunger following smoking abstinence.17 Leptin serum leves are higher in LCD like NAFLD and cholelithiasis also there have been reported different mechanisms of liver damage exerted by leptin like the induction to fibrosis associated to NAFLD.18

Although current smoking is related to a lower body mass index (BMI), it is not necessarily associated with a smaller waist circumference.19 In fact, some evidence suggests that smoking is related to visceral fat accumulation.20 Smoking cessation is associated with a substantial increase in waist circumference.21 How this affects mortality risk and whether this is independent of total adiposity is unknown. The combined relations of BMI and smoking on mortality have not been studied extensively. Both smoking and adiposity are independent predictors of mortality, but the combination of current or recent smoking with a BMI ≥ 35 or a large waist circumference is related to an especially high mortality risk.22 Besides, smokers in general tend to have a very sedentary life since the practice of physical exercise is difficult for them.

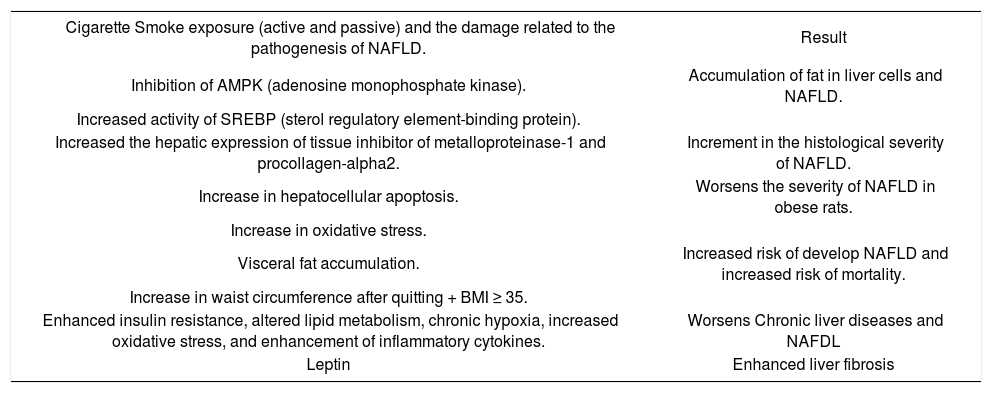

About tobacco, basic and clinical research have demonstrated that smoking alters enzymatic and inflammatory pathways in liver physiology, and is considered to be a risk factor for liver neoplasm, and affects the prognosis of chronic liver diseases (Table 1).23

Cigarette smoke damage and NAFLD.

| Cigarette Smoke exposure (active and passive) and the damage related to the pathogenesis of NAFLD. | Result |

|---|---|

| Inhibition of AMPK (adenosine monophosphate kinase). | Accumulation of fat in liver cells and NAFLD. |

| Increased activity of SREBP (sterol regulatory element-binding protein). | |

| Increased the hepatic expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 and procollagen-alpha2. | Increment in the histological severity of NAFLD. |

| Increase in hepatocellular apoptosis. | Worsens the severity of NAFLD in obese rats. |

| Increase in oxidative stress. | |

| Visceral fat accumulation. | Increased risk of develop NAFLD and increased risk of mortality. |

| Increase in waist circumference after quitting + BMI ≥ 35. | |

| Enhanced insulin resistance, altered lipid metabolism, chronic hypoxia, increased oxidative stress, and enhancement of inflammatory cytokines. | Worsens Chronic liver diseases and NAFDL |

| Leptin | Enhanced liver fibrosis |

Furthermore, mice exposed to secondhand smoke (combination of smoke exhaled by a smoker and smoke given off by the burning end of a tobacco product) during one year in the lab, showed fat accumulated in liver cells. The study focused on two key regulators of lipid metabolism that are found in many human cells as well: SREBP (sterol regulatory element-binding protein) that stimulates synthesis of fatty acids in the liver, and AMPK (adenosine monophosphate kinase) that turns SREBP on and off. It was found that secondhand smoke exposure inhibits AMPK activity, which, in turn, causes an increase in activity of SREBP. When SREBP is more active, more fatty acids get synthesized. The result is NAFLD induced by second-hand smoking.24

The mechanisms by which CS worsens chronic liver disease (CLD) include enhanced insulin resistance (IR), altered lipid metabolism, chronic hypoxia, increased oxidative stress, and enhancement of inflammatory cytokines. Because IR influences histological severity in NAFLD, CS may worsen NAFLD through its effect on IR, glucose intolerance, and diabetes development. Changes in lipid metabolism induced by CS may also aggravate NAFLD. Experimental studies have shown that CS aggravates the hepatic steatosis elicited by a high-fat diet in mice via enhanced fatty acid synthesis through inhibition of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase phosphorylation in liver tissue.25 Chronic hypoxia, a hallmark side effect of CS, induces steatosis, liver inflammation, and fibrosis in mice. CS also causes oxidative stress a recognized mechanism of injury in NAFLD. Mice on an ethanol diet develop increased hepatocellular injury when they are exposed to CS, and they have increased levels of cytochrome P450-2E1, which is known to play a role in oxidative injury in NAFLD. Finally, CS may worsen NAFLD by enhancing proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, that are known to play a key role in NAFLD8.25-27

Although two studies did not find an association between CS and the presence of NAFLD in the general population28,29 only one published clinical study has looked at the possible effect of CS in patients already identified as having NAFLD.30 In that study, CS exposure was associated with increased ALT. As Claudia Zein mentioned,27 future studies are needed to better elucidate the mechanistic aspects of the effects of CS in NAFLD and to better characterize the role of CS in human NAFLD. Nonetheless, now we have evidences that there is already ample experimental and clinical evidence consistently pointing in the same direction: CS aggravates liver injury in CLD. It is time to take the harmful effects of CS in CLD more serious

In summary, the study by Azzalini, et el.1 demonstrated that CS worsens liver injury in a rat model of obesity-related NAFLD. This results together with all the experimental and clinical information we have now, emphasizes the importance of an urgent change in the current medical approach on tobacco cessation. As in many medicine specialties, gastroenterologists and hepatologists MUST advise their smoker patients, with or without CLD, about the effect of this modifiable risk factor, encourage them to stop smoking, educate and help them to quit. There is no doubt that encouraging smoking cessation is one of the most cost-effective ways in which doctors can help to improve the health of their patients.