Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a lipid-enveloped virion particle that causes infection to the liver, and as part of its life cycle, it disrupts the host lipid metabolic machinery, particularly the cholesterol synthesis pathway. The innate immune response generated by liver resident immune cells is responsible for successful viral eradication. Unfortunately, most patients fail to eliminate HCV and progress to chronic infection. Chronic infection is associated with hepatic fat accumulation and inflammation that triggers fibrosis, cirrhosis, and eventually hepatocellular carcinoma. Despite that the current direct-acting antiviral agents have increased the cure rate of HCV infection, viral genotype and the host genetic background influence both the immune response and lipid metabolism. In this context, recent evidence has shown that cholesterol and its derivatives such as oxysterols might modulate and potentialize the hepatic innate immune response generated against HCV. The impairment of the HCV life cycle modulated by serum cholesterol could be relevant for the clinical management of HCV-infected patients before and after treatment. Alongside, cholesterol levels are modulated either by genetic variations in IL28B, ApoE, and LDLR or by dietary components. Indeed, some nutrients such as unsaturated fatty acids have demonstrated to be effective against HCV replication. Thus, cholesterol modifications may be considered as a new adjuvant strategy for HCV infection therapy by providing a biochemical tool that guides treatment decisions, an improved treatment response and favoring viral clearance. Herein, the mechanisms by which cholesterol contributes to the immune response against HCV infection and how genetic and environmental factors may affect this role are reviewed.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is one of the leading causes of chronic liver damage worldwide, at least 180 million people are infected with the virus, and it causes approximately 399,000 deaths every year.1 Eradication of HCV depends on several factors of the host and the virus that influence both the natural and pharmacologically-induced clearance of HCV in the infected patient. Among these are the host immune system and body metabolism which are continuously in communication to detect and eradicate different types of pathogens.2 A delicate balance between both systems is required to eliminate invading pathogens effectively.3 HCV is a small virus that restrings its infection to the liver, the metabolic organ by excellence.4 The hepatitis C life cycle stages such as transportation, entry, replication, translation, assembly, and release are accomplished through hepatic lipid pathways,5 and to meet the substrate and energy requirements that it demands, HCV hijacks the hepatocytes metabolic machinery.6 In consequence, patients with long-term infection develop excessive fat accumulation in the hepatocytes; in fact, steatosis is a histopathological feature typically found in patients with hepatitis C.7,8 Chronic inflammation and excess fat triggered directly by HCV are responsible for fibrosis, cirrhosis and eventually hepatocellular carcinoma.9

The first line of defense against HCV infection is orchestrated by the innate immune response,10 which is carried out by resident liver macrophages and dendritic cells that establish an interferon (IFN) antiviral state.11 During this stage, the immune response also targets lipid pathways as a strategy for successful viral eradication.12 A strong but controlled immune response allows that a small rate of patients spontaneously clear the infection.13 Nevertheless, most patients cannot evade virus replication and develop chronic disease.14 However, if they are treated with direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) regimens, patients will achieve high rates of sustained virological response (SVR).15

At current, there are several approved DAAs that have reached high efficacy in treatment against HCV infection.16–18 Nonetheless, the management of HCV infection has several caveats to defeat even with the new DDAs such as their high costs,19,20 the regional prevalence of difficult-to-treat genotypes such as genotype 1a21,22 and the emergence of antiviral-resistant mutations.23 Consequently, a high proportion of patients around the world who are treatment-naïve are at risk to develop complications of chronic infection.20 Therefore, understanding the synergic interactions between lipid pathways and innate immune response involved in the HCV life cycle may provide novel host therapeutic targets before and after treatment with DAAs. Also, host therapeutic targets could have the potential to be applied in all patients independently of viral genotype.

Gene expression studies have revealed that host immune and metabolic genes are differentially regulated during the early stages of the infection and this expression correlated with the clearance of the virus.24–26 Recent investigations have shown that cholesterol and cholesterol derivatives play a central role in the activation and orchestration of the innate immune response against HCV infection.27,28 Therefore, cholesterol modulation represents a promissory strategy for the clinical management of chronic patients before and after treatment. Also, it has been reported that cholesterol levels could be modulated either by variations of IL28B, ApoE, and LDLR host genes or by dietary components.29 Thus, cholesterol modifications may provide a plausible biochemical tool for making treatment decisions, improving treatment response and favoring viral clearance. This review summarizes the different mechanisms by which cholesterol and cholesterol derivatives modulate the innate immune response against HCV and how genetic and environmental factors affect this interaction.

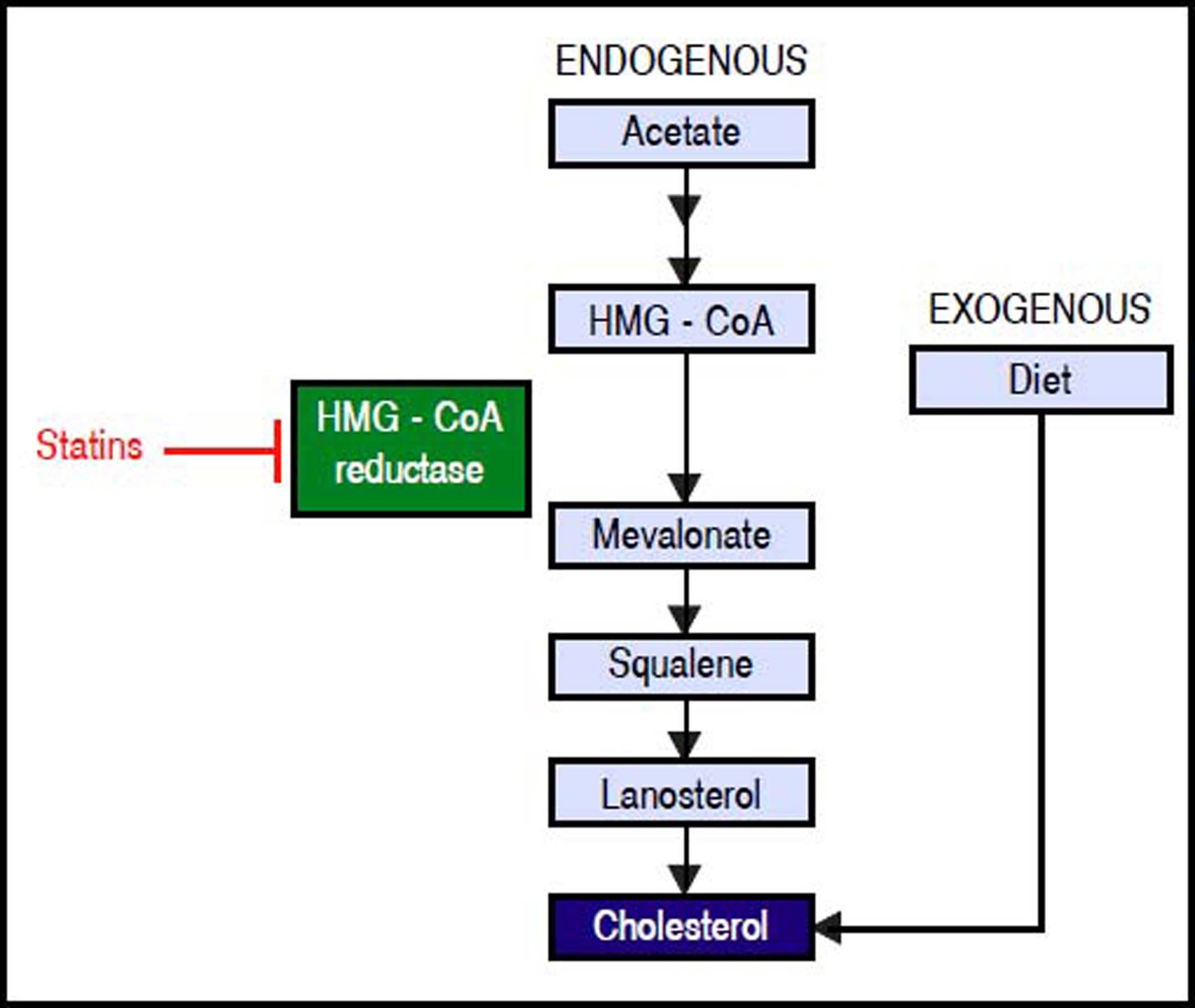

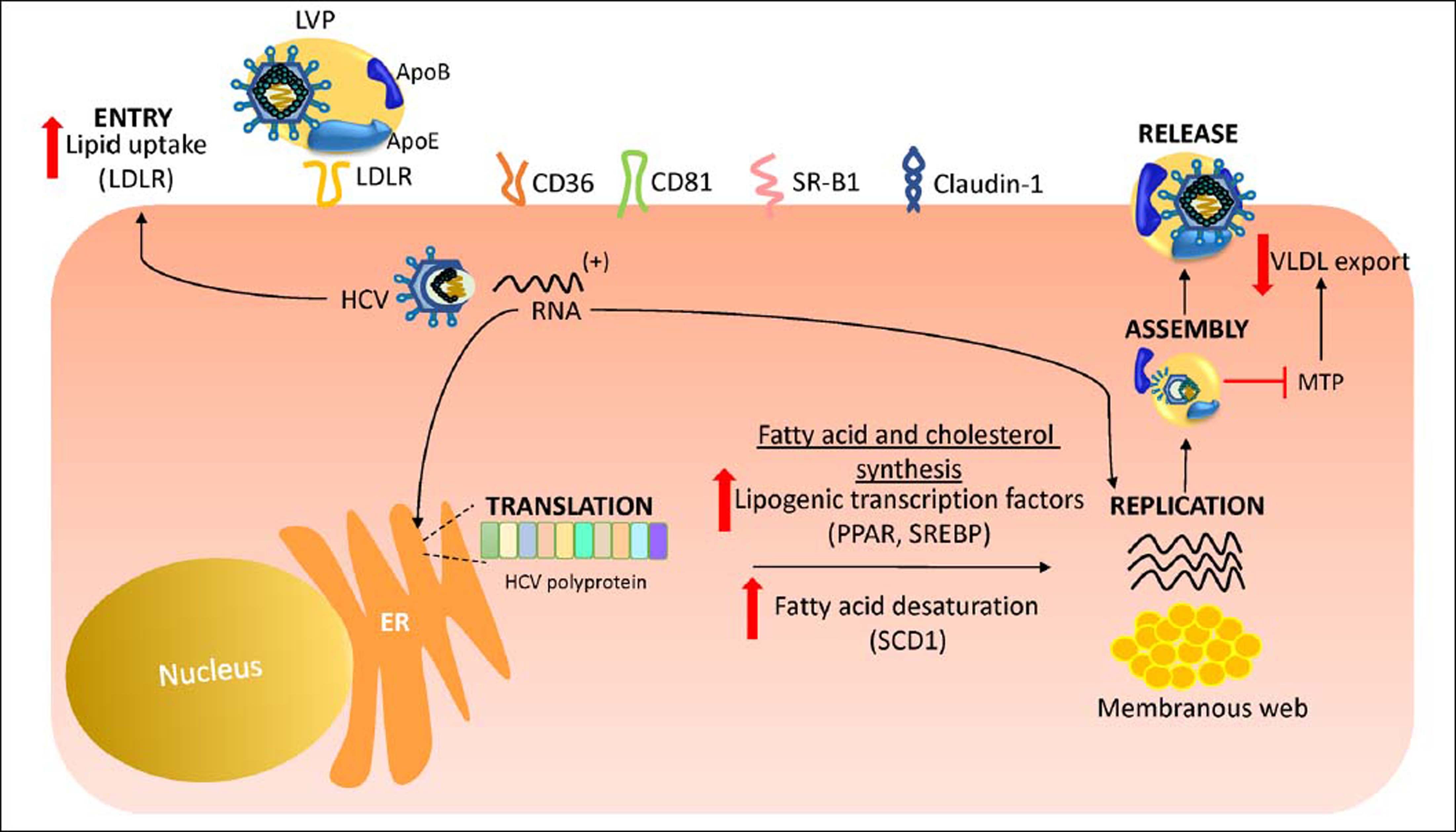

Hcv Life Cycle and up-Regulation of Cholesterol and Fatty acid BiosynthesisHCV is a lipid-enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Hepacivirus genus within the Flaviviridae family.30 HCV life cycle is mainly restricted to the liver which plays a key role in cholesterol homeostasis.3,31 Hepatocytes obtain cholesterol by endogenous synthesis via the mevalonate pathway or external sources from the diet (Figure 1).32 In the latter, cholesterol is internalized into the liver by low-density lipoprotein (LDL) ligated to the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol receptor (LDLR).33,34 After infection, HCV enters the bloodstream and binds to the lipoproteins rich in cholesterol esters which contain surface apolipoproteins E and B; this complex is termed lipoviroparticle (LVP).35 LVPs make HCV undetectable to antibodies and serum complement.36 Also, apolipoproteins of the LVP play a key role on virus attachment and entry into the hepatic cells, since they are ligands of the LDLR and other hepatic lipid-coreceptors.37,38 The intrahepatic HCV life cycle is highly dependant on hepatic cholesterol and lipogenesis pathways.39 During infection, HCV upregulates host lipid metabolism by a variety of molecular mechanisms which may eventually contribute to the development of hepatic steatosis that occurs in almost 55% of HCV-infected patients.6 In general, an intracellular environment rich in lipids including cholesterol is necessary for a successful HCV life cycle.3 As shown in figure 2, HCV uses LDLR and other lipid receptors expressed in hepatocytes surface (CD36, CD81, SR-B1, claudin-1) on entry.40,41 Once inside, HCV increases lipogenesis de novo and cholesterol biosynthesis via activation of the transcriptional factor sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) and reduces lipid export via the very-low density lipoproteins (VLDL).42,43 SREBP is an endoplasmic reticulum membrane-bound transcription factor that activates genes encoding enzymes of cholesterol and fatty acid biosynthesis.44,45 During its replication HCV induces the activity of stearoyl coenzyme A desaturase 1 (SCD1), an enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of monounsaturated fatty acids such as oleic acid.46 SCD1 is required for formation and regulation of HCV replication complex as its inhibition blocks HCV replication.47 Like other positive-sense RNA viruses, HCV life cycle needs a membrane web folding in the cytoplasm.48 This membrane web formation is dependent on the regulation of the cholesterol and unsaturated fatty acids metabolism.49 Finally, HCV also reduces lipid export by interfering VLDL excretion.43 Thus, low levelsof total cholesterol, LDL, VLDL and lipoproteins are found in the serum of chronic HCV patients.50 Hepatocellular lipid storage (steatosis) appears to be a direct consequence of HCV genotype 3. However, other genotypes have been associated with metabolic syndrome and obesity.51 Interestingly, recent reports have shown that the immune response stimulates specific metabolic pathways to decrease the rate of HCV replication,52,53 a finding that highlights the potential role of metabolism as a target for the inhibition of HCV infection.

Endogenous synthesis and exogenous acquisition of cholesterol. Schematic representation of endogenous cholesterol synthesis and exogenous cholesterol acquisition from the diet. Statins impairs cholesterol synthesis through the inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase enzyme activity. Statins indirectly impairs HCV genome replication. HMG-CoA: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutharyl-coenzyme A.

HCV life cycle and up-regulation of cholesterol and fatty acid biosynthesis. During its replicative life cycle, HCV induces the expression of transcription factors involved in cholesterol and fatty acid biosynthesis favoring an environment rich in lipids. Aso, HCV increases LDLR expression in hepatocyte surface to favor its entry. In addition, HCV blocks the excretion of VLDL through MTP down regulation. ER: endoplasmic reticule. LVP: lipoviroparticle. LDLR: lowdensity lipoprotein receptor. ApoE: apolipoprotein E. SCD1: stearoyl coenzyme A desaturase 1. SREBP: sterol regulatory element-binding protein. VLDL: verylow density lipoprotein. SR-B1: scavenger receptor class B type 1. MTP: microsoma triglyceride transfer protein.

A strong innate immune response against HCV during the acute phase is responsible for natural HCV clearance.54 Bench to bedside research has provided increasing evidence about the cross-talk between cholesterol and immunity.2,55 In the context of HCV infection, recently, cholesterol and its derivatives have emerged as immunomodulators that potentialize the innate immune response and may favor the natural or treatment-induced clearance of the virus.28,56 There is evidence that cholesterol promotes the formation of toll-like receptor (TLR) 4-MD2 and TLR4-CD14 complexes, which are responsible for recognizing lipopolysaccharides as part of the innate immune response.57 A study performed in an HCV-pro-ducing B-cell line derived from an HCV+ non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, demonstrated that activation of TLR4 by HCV infection triggers the expression of IFN-beta and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in B cells.58 Since IL-6 leads inflammatory processes and IFN induces an antiviral state in HCV infection,59,60 these findings suggest that cholesterol can play an indirect role in HCV eradication by contributing to the host’s innate immune response. Also, through Vero cells culture infected with WNVKUN strain MRM61C or WNVNY99 it was demostrated that changes in the intracellular distribution of cholesterol could disrupt lipid rafts and modulate the IFN JAK-STAT signaling pathway during Flavivirus infections.61 Similarly, it has been recently demonstrated in patients infected by genotype 1 that LDL increased interferon sensitivity.62,63 Also, high LDL levels correlate with IFN activity; this finding was demonstrated through the detection of IFN-gammainducible protein 10 (IP10), a chemokine induced by IFN and produced by T cells, monocytes and natural killer cells after HCV infection.64 Thus, it is plausible that high serum LDL levels could participate in inducing innate immune response and favoring natural clearance. Another plausible mechanism in which LDL can prevent HCV infection is by direct competition with the attachment and entry of the virus through the membrane surface liporeceptors on the hepatocyte, mainly LDLR.27 Lastly, gene polymorphisms of cholesterol metabolism could be an important factor in the variations of cholesterol and LDL levels which can also affect the immunoregulatory effect of cholesterol.65 Some of the most important polymorphisms in genes related to HCV outcome are described in the next sections.

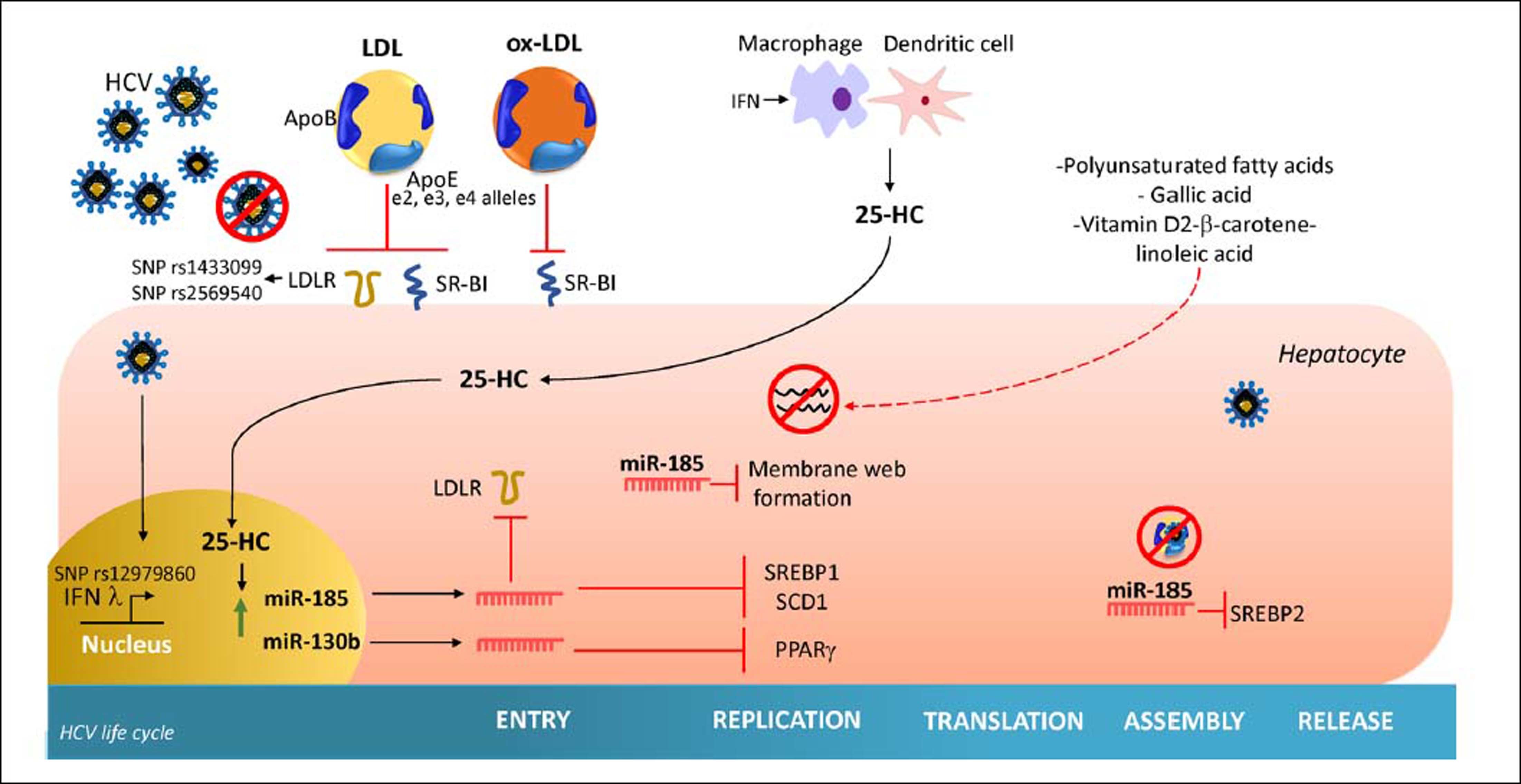

Oxidized-LDLOxidized-LDL (ox-LDL), a naturally occurring derivative of native LDL that has undergone oxidative modification, is a potent endogenous inhibitor of HCV cell entry in all genotypes.66 Ox-LDL inhibits in a non-competitive manner the binding of HCV with class B scavenger receptor I (SR-BI), an essential receptor for HCV attachment. Thus, ox-LDL can inhibit cell-to-cell spread in vitro.66 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that ox-LDL directly modifies viral particle morphology. However, the exact mechanism has not been elucidated.67 The participation of ox-LDL in HCV cycle is evident since chronic HCV-patients have higher serum levels of ox-LDL than control subjects68 and high ox-LDL before treatment has demonstrated to have an impact on increasing the SVR of treatment with peg-IFN plus Ribavirin.69 Also, it was reported that 8.85 mU/L of ox-LDL is the optimal cutoff in serum to reach adequate SVR.69

Besides, ox-LDL is engulfed by macrophages which amplify the TLR-4 signaling.70 Increased TLR-4 activity leads to the augmented production of cytokines, chemokines and inflammasome activation. Thus ox-LDL could be responsible for an increased immune response. However, it is necessary to elucidate if it can trigger liver damage. Given its potential involvement in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, ox-LDL is an unlikely indirect therapeutic component. Nonetheless, molecules that mimic its anti-HCV mechanism would be an attractive indirect therapeutic against HCV infection.

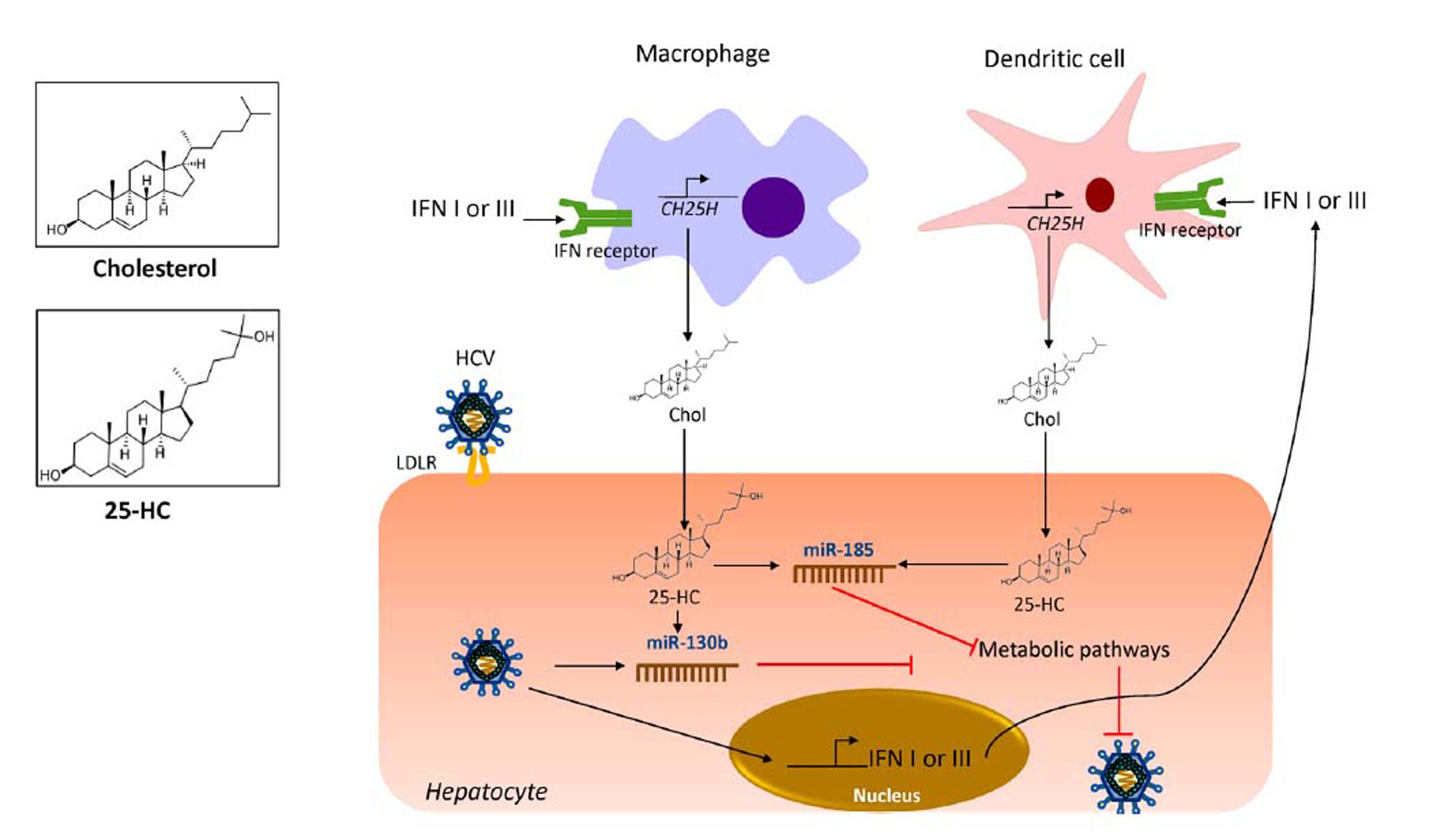

OxysterolsOxysterols are a family of metabolite derivatives of cholesterol oxidation that present remarkable diverse biological activities.28 To date, three naturally occurring oxysterols, 24-hydroxycholesterol (HC), 25-HC and 27-HC have been recognized. Of these, 25-HC plays a key role in the regulation of different cellular process such as lipid metabolism, modulation of immune response and suppression of viral pathogenesis.71 It was recently reported that 25-HC is part of the primary immune response against HCV infection since it regulates IFN response.53 As shown in figure 3, during HCV infection, IFN I or III induce the production of 25-HC by dendritic cells and macrophages residents of the liver.72 IFN induces the expression of the cholesterol 25-hydroxylase (CH25H) enzyme, which catalyzes the oxidation of cholesterol to 25-HC by the addition of a hydroxyl group on the side chain.73

25-hydroxycholesterol as part of the innate immune response against HCV. Once HCV has infected hepatocytes, the expression of IFN induces the expression of CH25H in macrophages and dendritic cells residents of the liver. The CH25H converts cholesterol into 25-HC. The 25-HC may exert an autocrine or paracrine antiviral lipid effect. 25-HC induces the expression of miR-185 and miR130b in the hepatocytes which results in inhibition of key pathways needed for HCV life cycle. CH25H: cholesterol-25-hydroxylase; HCV: hepatitis C virus. Chol: cholesterol. 25-HC: 25-hydroxycholesterol. IFN: interferon. LDLR: low density-lipoprotein receptor. miR-185: microRNA 185. miR-130b: microRNA 130b.

Once secreted, 25-HC may exert its antiviral effect in an autocrine or paracrine manner. Inside the hepatocyte, 25-HC stimulates the secretion of two hepatic microR-NAs (miRNAs), miR130b and miR-185 (Figure 3).28 miR-185 decreases mRNA expression of several lipid targets known to encode proteins critical for different stages of HCV life cycle such as, fatty acids and cholesterol biosynthesis (SREBP), lipid uptake (LDLR, SR-B1) and fatty acid desaturation (SCD1) (Figure 4).74,75 miR-185 can inhibit HCV replication through down-regulation of SCD1, entry and cell transmission through SCARB1, replication, and assembly through SREBP and entry and replication through LDLR. Likewise, miR-130b can repress the expression of LDLR, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARy).28 In addition to these antiviral effects, CH25H and 25-HC may block membrane web formation required for the successful HCV-replication through miR-185 action. Also, using human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line Huh7.5.1 and HCV-JFH1 strain (genotype 2a), it was demonstrated that CH25H inhibits non-structural 5A (NS5A) dimer formation of the HCV replication complex.76 Similarly, in Huh7.5 hepatoma cells infected with JFH-1T and full-length genomic replicon (genotype 1b) it was demonstrated that 25-HC might inhibit HCV replication in hepatocytes.28 Also, serum levels of both CH25H and 25-HC were elevated in patients infected with HCV.77 On the other hand, it has been demonstrated that HCV counteracted 25-HC antiviral effects through inhibition of miR-185 and miR130b expression.28 Collectively, this finding highlights the importance of 25-HC as a member of the immunometabolic process generated during HCV infection.

Effect of cholesterol derivatives and diet in HCV life cycle. The cholesterol and cholesterol derivatives inhibit key specific steps required by HCV entry, replication and assembly. In addition, polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin D, β-carotene and linoleic acid interaction inhibit HCV replication. HCV: hepatitis C virus. 25-HC: 25-hydroxycholesterol. LDLR: low density-lipoprotein receptor. miR-185: microRNA 185. miR-130b: microRNA 130b. ApoE: apolipoprotein E. ApoB: apolipoprotein B. ox-LDL: Oxidized-low density-lipoproten. SCD1: stearoyl coenzyme A desaturase 1. SREBP1: sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1. SREBP2: sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2. SR-B1: Scavenger receptor class B type 1.

The effect of baseline cholesterol levels on viral clearance induced by antiviral treatment based on IFN + ribavirin has been documented.78 Importantly, this effect also remains with the new IFN-free DAAs.62,79 For example, high levels of total cholesterol, LDL and body mass index (BMI) were predictors of SVR and subsequent resolution of liver damage on patients treated with peg-IFN or triple therapy for genotype 1.56,78,80,81 Also, a rapid increment of LDL in chronically-infected patients after the beginning of IFN-free treatment was reported.79 This evidence supports the concept that suppression of HCV infection would reduce the lipid droplets of infected hepatocytes and rebound of serum LDL and total cholesterol in the infected patient.

Statins were initially developed to treat patients with hypercholesterolemia and its function at the molecular level is to inhibit 3-hydroxy-3-metil-glutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase, the key regulatory enzyme of the endogenous mevalonate pathway of cholesterol synthesis (Figure 1).82,83 In this sense, HCV infected patients are at risk of cardiovascular disease and statins utilization are currently part of several guidelines to prevent cardiovascular events.82 Moreover, correlations between statins and HCV life cycle has been reported. For instance, in vitro Fluvastatin impairs HCV genome replication through the downregulation of CLDN-1 protein implicated in cell entry and in combination with IFN treatment its effect is potentialized.84 In contracts, pravastatin showed a proviral effect by upregulation the transcription of LDLR, then favoring HCV infectivity.85,86 All those findings suggest that modulation of metabolic machinery, specifically cholesterol pathways, could be a reliable strategy to attack HCV infection. In addition, this findings could be also extended to another flavivirus members as, dengue and west Nile viruses whose life cycles are also closely related with cholesterol pathway.61

Genetic Modulation of Cholesterol In HCV InfectionThe outcome of HCV infection is influenced by a complex interaction between environmental, viral and host factors.29 Marked differences in HCV infection outcome have been reported by ethnicity.87–89 Regarding genetic host factors, numerous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) confer genetic susceptibility to chronic HCV infection or clearance, worldwide (Figure 4).90 Thus, different grades of association could be found between populations. Therefore, genetic studies should be done to determine the susceptibility in each population to provide individualized medicine.91 Genetic variants involved in cholesterol homeostasis that alter the expression and function of the proteins may consequently influence HCV-infection result, some of which are described below.

IL28BInterleukin 28-B (IL28B) identified in 2003 belongs to the interferon lambda family.92 This cytokine is released by dendritic cells during HCV infection.93 The gene encoding IL28B is located at locus 19q13.13.94 Several genome-wide association studies involving populations with different ethnicities have demonstrated that SNP rs12979860C/T in the promotor region is a variant highly associated with clearance of the infection, naturally or induced by treatment.95–98 This association have been replicated in several individual studies carried out in specific populations around the world.99–101 Interestingly, Li and coworkers in 2010, reported that rs12979860CC genotype was associated with higher LDL, total cholesterol and ApoB serum levels but low ApoE and LVP of patients with chronic HCV infection.102 This association was present only in subjects with active viremia whereas patients who cleared the virus did not exhibit lipid alterations.102 Although the exact mechanism of this association remains unknown, we hypothesized that CC genotype carriers in the presence of the virus could have had lower IFN lambda activity or intrahepatic interferon signaling; this hypothesis is reinforced by a study showing that CC genotype carriers had low levels of IP10 protein, an indirect chemokine marker of IFN activity.103 However, the role that cholesterol plays in this association remains to be elucidated.

ApoEHCV in serum is found attached to lipoproteins which contain ApoE.104 HCV NS5A interacts with ApoE to bind to the LVP. Indeed, silencing ApoE expression results in a reduction of HCV infectivity, less entry and replication processes.105 As shown in electron microscopy, ApoE is abundant in the LVP surface and is the ligand of LDLR, thus permitting the entry of HCV into the hepatocyte.64,106ApoE gene is located on chromosome 19, two SNPs rs429358C/T and rs7412C/T located in exon 4 encode e2, e3, and e4 alleles.104 The expression of these alleles produces the corresponding e2, e3 and e4 isoforms which differ in an amino acid residue. The e3 isoform presents cysteine at residue 112 (rs429358) and arginine at residue 158 (rs7412), while e2 contains a cysteine at both positions, and e4 has arginine at both positions. The amino acid substitution changes the affinity of ApoE to the LDLR receptor. The isoform e2 shows lower affinity for LDLR and decreases the entrance of HCV into the hepatocyte compared to the e3 isoform that has a natural affinity, whereas e4 isoform has higher affinity for LDLR and allows a rapid entry into the hepatocyte. In addition to the different affinities, these isoforms show different immune regulation.107 Low ApoE concentration is associated with early virological response in HCV patients and it was demonstrated by the high expression of IP10.62 These findings support the hypothesis that modulation of cholesterol level could be used to limit HCV propagation. Also, ApoE isoforms are related to different profiles of serum and intrahepatic lipid levels.108 Some studies have reported the association of e3 allele with chronic HCV infection,109 while the e4 allele has been associated with protection to severe liver damage in HCV patients.110 However, variations of the ApoE alleles have been reported by ethnicity, therefore, population studies are needed to clarify its participation in HCV infection.

LDLRPolymorphisms in the LDLR gene are associated with familial hypercholesterolemia, atherosclerosis, and obesity.111,112 However, in the context of HCV infection, LDLR recognizes the E2 viral protein and allows the HCV entry to the cell.33 Two SNPs in the LDLR gene rs1433099A/G and rs2569540G/C are associated with lower viral load and lower levels of LDL and cholesterol in patients genotype 1 and 4.113 It has been reported an interaction between IL28B and LDLR.114 Since IFN induces expression of LDLR gene that could be a reason why IFN treated patients have reduced serum cholesterol levels.115 Furthermore, intracellular levels of HCV-RNA in primary hepatocytes correlate with LDLR mRNA expression, and the uptake of LDL particles.33 Since IFN can stimulate soluble form of LDLR in cell culture and that soluble LDLR can inhibit HCV infectivity, LDLR can exert an antiviral effect against HCV infection.116

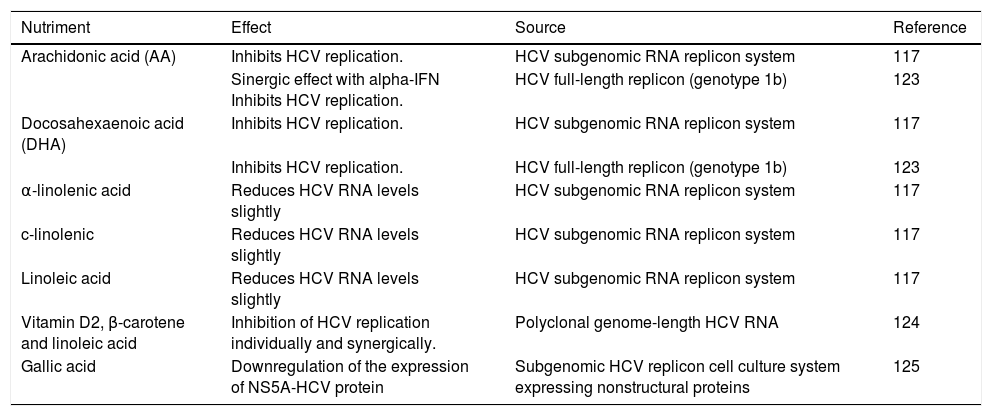

Impact of Dietary Components On HCV ReplicationThe effect of dietary components on the HCV life cycle is mostly unknown. Since diet can modify serum lipid levels, the study of their impact on HCV infection could be considered as a strategy of HCV management. HCV regulates by direct and indirect mechanisms the expression of several hepatic transcriptional factors involved in lipid metabolism.39At current, different nutrients have demonstrated to down regulate the replication of HCV in vitro, some of which are summarized in table 1 and figure 4. Most of these nutrients are unsaturated fatty acids; in contrast, high levels of saturated fatty acids have been reported to increases the rate of HCV replication in vitro.117 Also, it has been reported that oxysterols might be acquired through dietary animal fat. A recent in vitro study demonstrated that exogenous 25-HC could also trigger innate immune response.118 Thus, a diet composed of nutrients that have been related to inhibiting HCV replication could be considered as a therapeutic alternative against host factors that promote HCV infection among patients. However, more studies are needed in order to evaluate their effect in vivo.

Nutrients with anti-HCV replicative activity.

| Nutriment | Effect | Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arachidonic acid (AA) | Inhibits HCV replication. | HCV subgenomic RNA replicon system | 117 |

| Sinergic effect with alpha-IFN Inhibits HCV replication. | HCV full-length replicon (genotype 1b) | 123 | |

| Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) | Inhibits HCV replication. | HCV subgenomic RNA replicon system | 117 |

| Inhibits HCV replication. | HCV full-length replicon (genotype 1b) | 123 | |

| α-linolenic acid | Reduces HCV RNA levels slightly | HCV subgenomic RNA replicon system | 117 |

| c-linolenic | Reduces HCV RNA levels slightly | HCV subgenomic RNA replicon system | 117 |

| Linoleic acid | Reduces HCV RNA levels slightly | HCV subgenomic RNA replicon system | 117 |

| Vitamin D2, β-carotene and linoleic acid | Inhibition of HCV replication individually and synergically. | Polyclonal genome-length HCV RNA | 124 |

| Gallic acid | Downregulation of the expression of NS5A-HCV protein | Subgenomic HCV replicon cell culture system expressing nonstructural proteins | 125 |

Similarly, the importance of cholesterol diet modifications was demonstrated by a study performed in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Chronic patients received a normocaloric low cholesterol diet for 30 days. The diet restored the immune homeostasis and recovered the balance between Th17 and Treg cells, subduing the exacerbation that can induce chronic liver damage.119

As previously mentioned, high baseline levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, and BMI are associated with high rates of SVR in treatment with IFN and IFN-free regimens. Both, cholesterol alterations and BMI are related to obesity. Obesity prevalence has grown over the last decades worldwide. Obese adults are at high risk to present high cholesterol and triglycerides level and decreased high-density lipoprotein levels than normoweight subjects.120 It has been hypothesized that in countries with high rates of overweight and obesity like the United States and Mexico, metabolic alterations could contribute to the progression of the hepatitis C.29 In conjunction, dietary modifications aimed to prevent the HCV life cycle may be considered as a useful tool for HCV management. However, given the wide variations of genetic backgrounds, diet composition, and dietary habits worldwide, their impact on HCV life cycle should be studied independently by populations or regions.121,122

ConclusionsIn this review, the immunometabolic effect of cholesterol in HCV infection was approached. In conjunction with the pharmacological use of DDAs regimens, HCV clearance may be enhanced by the immunoregulatory effect of cholesterol derivatives like 25-HC in the liver resident innate immune cells. The levels of cholesterol and cholesterol derivatives may provide a potential tool for making decisions on drug treatment and improve its efficacy against HCV infection. LDL could be one of the most promising pretreatment biochemical and metabolic marker for predicting induced-SVR and natural HCV clearance. The alterations of the host metabolic pathways have the potential to define new strategies for the development of aduyvant antiviral treatments.

However, it is important to keep in mind that the genes encoding both the immune response (IL28B) and lipid metabolic (Apo E, LDLR) pathways are host factors that display adaptive structural variations (SNPs) that have a heterogenic distribution throughout the populations worldwide. On the other hand, the viral genotype also displays differences in lipid disruption, treatment response and emergence of antiviral-resistant mutations. Furthermore, the modulatory effect of environmental factors such as dietary composition on lipid abnormalities requires attention. However, the food source and the amount of food intake are parameters that may vary drastically by region. Currently, the rising incidence of nutrition-related diseases such as obesity imposes an additional risk factor that can affect the course of the infection in HCV-infected patients with weight problems. Therefore, in the implementation of the novel strategies that have been reviewed it is necessary to consider how these genetic and environmental factors modify the clinical management and the efficacy of antiviral therapy of HCV infection. Further investigation based on these factors by population is needed to achieve tailoring these strategies in an individualized manner.

Abbreviations- •

ApoE: apolipoprotein E.

- •

BMI: body mass index.

- •

CH25H: cholesterol 25-hydroxylase.

- •

DAAs: direct antiviral agents.

- •

HC: 24-hydroxycholesterol.

- •

HCV: hepatitis C virus.

- •

IFN: interferon.

- •

IP10: IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10.

- •

LDL: low-density lipoprotein.

- •

LDLR: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol receptor.

- •

LVP: lipoviroparticle.

- •

miRNAs: microRNAs.

- •

ox-LDL: oxidized-LDL.

- •

PPARy: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma.

- •

SCD1: stearoyl coenzyme A desaturase 1.

- •

SNPs: single nucleotide polymorphism(s).

- •

SREBP: sterol regulatory element-binding protein.

- •

SVR: sustained virological response.

- •

TLR: toll-like receptor.

- •

VLDL: very-low density lipoprotein.

This work was supported by PRODEP-Universidad de Guadalajara CA-478 to all authors.

Conflict Of InterestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.