Background: Diabetes mellitus (DM) is recently identified risk factor for development and progression of chronic liver disease as well as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). We planned a prospective analysis to identify impact of DM in Indian patients with HCC. Methods: During last 10 years, 160 consecutive patients of HCC were evaluated. Demographic profile like age of presentation, clinical features, etiology of HCC, tumor size at presentation, management and ultimate outcome was compared diabetic with non-diabetic HCC patients. Results: During last 10 years, 160 consecutive patients of HCC were evaluated (Mean age = 59.6 ± 12.9 years, sex ratio (M: F) = 5.4: 1). Etiology for HCC were hepatitis B in 45 (28.2%), hepatitis C in 18 (11.3%), alcohol in 27 (16.8%), alcohol with hepatitis B in 12 (7.5%), alcohol with hepatitis C in 1 (0.6%), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in 4 (2.5%) and cryptogenic in 53 (33.2%) patients. Patients of HCC with DM (group-A, n =46, age = 62.6 ± 9.5 years, sex (M: F) = 6.6:1) were compared with patient of HCC without DM (group-B, n =114, age = 66.7 ± 13.7 years, sex (M: F) = 5.4:1). Duration of diabetes in group-A was 7.6 ± 3.2 years. Patients in group-A had more advanced HCC (size of lesion > 5 cm and >3 lesions of 3 cm or more diameter, portal vein thrombosis or intra-hepatic bile duct involvement) than group-B [34 (73.9%) vs 72 (54.3%)]. Mortality with in one year was significantly more in group-A compared to group-B [36 (78.2%) vs 56 (49.1%)]. Conclusion: DM is associated with more advanced lesion and poor outcome in patient with HCC.

Type-2 diabetes mellitus (DM) increases risk of development of chronic liver disease (CLD).1 Commonest CLD in DM is non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).2 Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) occurs in patients with CLD and mostly in presence of cirrhosis. Known predisposing causes of HCC are hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus (HCV), chronic alcohol abuse, hemochromatosis and, recently, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).3 Cryptogenic cirrhosis remains responsible for HCC in 15-50% cases.4,5

Although earlier studies denied the association between type-2 diabetes mellitus (DM) and HCC;6-8 in most of the recent studies, DM is shown to increase risk of HCC by 2-to 4-fold, even after adjusting for other predisposing factors.5,9-29 In presence of viral hepatitis and alcohol intake, DM increases risk for HCC by 10-fold.25 DM is a major risk factor for NAFLD,30-33 which is shown to predispose for cryptogenic cirrhosis34 and HCC.35-37 There is increased incidence of DM in HCV infection, a known risk factor for HCC. Cirrhosis itself is diabetogenic state and also a predisposition for HCC. Diabetes is a risk factor, if not actually etiologic for HCC, but temporal relationship is not yet clearly defined.9,27 Only few studies have shown DM to precede HCC.1,38 World-wide, incidence of DM as well as HCC is increasing.1 India is experiencing an epidemic of DM.39 Establishing epidemiological relation and cause-effect relationship between these two is important.

There are only few studies on impact of DM on management and outcome of HCC. None of the studies from India have shown relation of DM with HCC. This study was planned to evaluate impact of DM on management and outcome of HCC.

Materials and methodsThis case-control observational study was carried out over study period of 10 years (1997-2006) on all the consecutive patients of HCC. Diagnosis of HCC was based on hyper-vascular tumor in the liver on two imaging studies or hyper-vascular tumor on single imaging modality with serum alpha-fetoprotein level greater than 400 ng/dL.

Patients were divided into 2 groups: a) Diabetic patients with HCC and b) Non-diabetic patients with HCC. Diabetes was diagnosed according to American Diabetes Association criteria on the basis of use of oral hypoglycemic drugs; fasting plasma glucose level • •126 mg/dL; 2-hour plasma glucose • •200 mg/dL during oral glucose tolerance test; and/or random or 2-hour post-prandial plasma glucose level • •200 mg/dL.

In both groups following features were noted: age of presentation, clinical features, laboratory features, Child class (CPT score), etiology (hepatitis B, hepatitis C, alcohol, NASH or other etiologies), tumor characteristics at presentation (advanced HCC), management (resection and ablative therapy or palliative management) and survival. Advanced HCC (morphological) was diagnosed on basis of tumor size > 5 cm or > 3 tumors each measuring > 3 cm diameter or portal vein thrombosis or bile duct invasion.

Statistical analysis was performed using Chi square test and student t test.

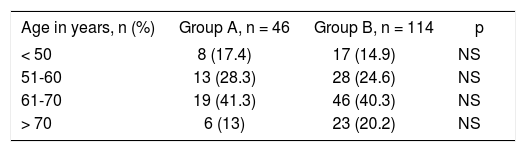

ResultsAs seen in Table I, majority of the patients in both groups were in age group 51-70 years. There was no statistically significant difference in both the study groups regarding age distribution.

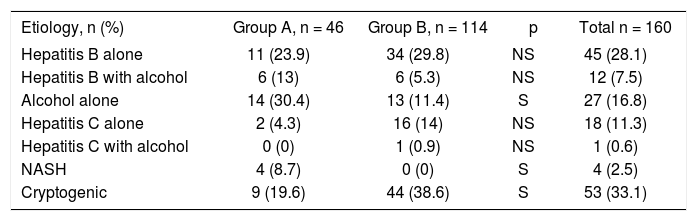

Different etiologies of HCC are tabulated in Table II. As an etiology for HCC, alcohol and NASH were significantly higher in group-A.

Different etiologies of HCC.

| Etiology, n (%) | Group A, n = 46 | Group B, n = 114 | p | Total n = 160 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis B alone | 11 (23.9) | 34 (29.8) | NS | 45 (28.1) |

| Hepatitis B with alcohol | 6 (13) | 6 (5.3) | NS | 12 (7.5) |

| Alcohol alone | 14 (30.4) | 13 (11.4) | S | 27 (16.8) |

| Hepatitis C alone | 2 (4.3) | 16 (14) | NS | 18 (11.3) |

| Hepatitis C with alcohol | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) | NS | 1 (0.6) |

| NASH | 4 (8.7) | 0 (0) | S | 4 (2.5) |

| Cryptogenic | 9 (19.6) | 44 (38.6) | S | 53 (33.1) |

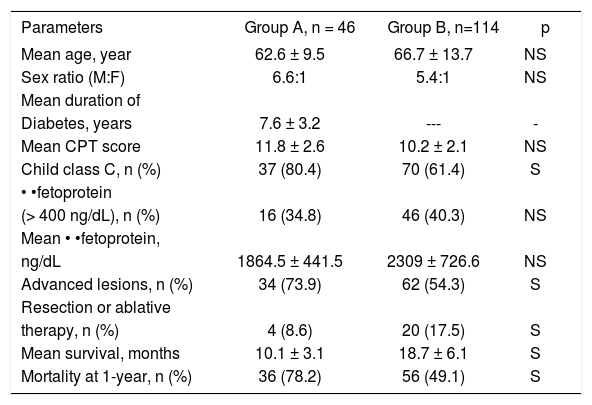

As seen in Table III, in group-A there was higher child class C patients and more advanced HCC. Also there was lower rate of curative treatment for HCC. Mortality rates at 1-year were higher in group-A.

Presenting features and outcome of both groups.

| Parameters | Group A, n = 46 | Group B, n=114 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, year | 62.6 ± 9.5 | 66.7 ± 13.7 | NS |

| Sex ratio (M:F) | 6.6:1 | 5.4:1 | NS |

| Mean duration of | |||

| Diabetes, years | 7.6 ± 3.2 | --- | - |

| Mean CPT score | 11.8 ± 2.6 | 10.2 ± 2.1 | NS |

| Child class C, n (%) | 37 (80.4) | 70 (61.4) | S |

| • •fetoprotein | |||

| (> 400 ng/dL), n (%) | 16 (34.8) | 46 (40.3) | NS |

| Mean • •fetoprotein, | |||

| ng/dL | 1864.5 ± 441.5 | 2309 ± 726.6 | NS |

| Advanced lesions, n (%) | 34 (73.9) | 62 (54.3) | S |

| Resection or ablative | |||

| therapy, n (%) | 4 (8.6) | 20 (17.5) | S |

| Mean survival, months | 10.1 ± 3.1 | 18.7 ± 6.1 | S |

| Mortality at 1-year, n (%) | 36 (78.2) | 56 (49.1) | S |

Previously, DM is shown to be a bad prognostic factor for long-term survival of cirrhotic patients and mortality mainly being related to liver failure.40

Among 7 studies done to find out impact of DM on HCC management, with few exceptions, most have shown increased post-resection complications and decreased post-resection survival, most probably due to increased risk of hepatic decompensation in DM.41-47 In our study, DM is associated with morphologically advanced lesions and with advanced liver disease regardless of etiology. This can be a deciding factor for delineating management strategies, namely surgical resection, percutaneous therapies and trans-arterial chemoembolization. Our study also shows that DM has adverse prognosis in HCC with high 1-year mortality rate.

It is still unclear whether HCC occurs because of insulin resistance, which leads to NASH, which leads to cirrhosis, or whether the stimulatory effects of insulin on hepatocyte growth lead more directly to neoplasia. Recent studies have thrown light on how DM leads to HCC. DM is a state of hyperinsulinemia. Hyperinsulinemia may directly induce HCC: 1. by the up-regulation of receptors of specific growth factors (insulin and insulinlike-growth factor-1);48,49 2. by activating mitogen activated kinase that leads to phosphorylation of insulin receptor substance-1(IRS-1) a key protein involve in cellular proliferation.50,51 Insulin resistance may play a role by increasing oxidative stress and generation of reactive oxygen species that leads to a. p53 tumor suppressor gene mutation via by-product of lipid peroxidation (4-hydroxynoneal),52,53 or b. up-regulation of proinflammatory cytokines. Thus, inflammation, cellular proliferation, apoptosis inhibition and tumor suppressor gene mutations in setting of advanced liver disease (as a result of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia) may lead to HCC formation. Hyperinsulinemia is associated with increased risk of HCC as well as it is shown to increase growth rate of HCC.54,55

In conclusion, Diabetic patients with HCC had more advanced liver failure, morphologically more advanced lesions and poorer long-term prognosis compared to non-diabetic patients with HCC.