Introduction. It is known that patients with chronic hepatitis C have a lower health-related quality of life (HRQOL) than the general population and evidence suggests that the hepatitis C virus (HCV) could exert direct neuropathic action on HRQOL. From this perspective, the virus clearance should be accompanied by improvement in HRQOL. Thus, we sought to review systematically the evidence in the literature and perform a meta-analysis of HRQOL changes caused by sustained virologic response (SVR).

Material and Methods. The PubMed was searched using the keywords Hepatitis C, Quality of Life and Therapy. The reviewers came to a consensus on articles that were selected to full reading and those that should be included in the study and a meta-analysis was performed of mean change difference between responders and non-responders.

Results. Eleven studies were included in the systematic review and four in the metaanalysis. Of these, nine studies showed more favorable outcome for responders, and they had a better outcome even in studies that evaluated only cirrhotic patients, previous non-responders, relapsers, patients in first treatment and patients unaware of treatment response. Moreover, the meta-analysis showed that the general health and vitality domains had statistically significant mean change difference between responders and non-responders, presenting a summary effect of 6.3 (CI 95% 2.5-10.0) and 7.8 (CI 95% 3.4-12.1) respectively.

Conclusion. There is evidence indicating that SVR is accompanied by an improvement in HRQOL and patients reaching SVR have clinically relevant improvement in domains of general health and vitality.

The chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a globally widespread disease affecting approximately 3% of the world’s population.1 Although silent, chronic hepatitis C (CHC) can evolve toward liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. In most patients, the disease manifests through subjective symptoms as fatigue, malaise, musculoskeletal pain, reduced cognitive function and mental clouding2,3 and it is now clear that chronic infected individuals have lower health-related quality of life (HRQOL) scores than the general population.4–9

The source of this quality of life impairment is still not completely known, but there are many factors that exert some impairment and a multifactorial origin may be the best explanation. Some studies have proved that alanine transaminase (ALT) levels and histological damage poorly explain the HRQOL reductions, since individuals with mild or moderate liver disease and normal levels of ALT also face a HRQOL impairment.5,9,10 However, other studies have shown that host factors, such as low total household income,9 awareness of the diagnosis11 and intravenous drug use9,12 are most likely to be the largest source of impairment. It is also well established that psychiatric diseases, such as depression, are responsible for some reduction in quality of life.13

On the other hand, the evidence of viral replication in the central nervous system14,15 and the neurocognitive impairment present in these patients2,16,17 raise the possibility of direct viral action on quality of life. From this perspective, the viral clearance achieved through antiviral therapy should be accompanied by an improvement of HRQOL. Regardless of the importance of this data to elucidate the source of HRQOL reduction and the great numbers of antiviral therapy clinical trials for HCV infection, the information about the improvement on HRQOL after the achievement of the sustained virologic response (SVR) is unclear and fragmented.

In this paper, the authors aim to systematically review evidence of change in HRQOL provoked by the achievement of SVR after antiviral therapy for treatment of HCV infection. This was achieved by gathering data from prospective studies that analyze HRQOL in patients at baseline and 24 weeks after the completion of treatment.

Material and MethodsStudy designThe authors’ objective was to identify all prospective studies evaluating the change in the HRQOL at baseline and 24 weeks after the end of treatment’ dividing patients by treatment response.

The authors restricted the selected studies to only those who used the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) health survey questionnaire,18 since it is available in several languages, has demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties in a variety of populations of patients with chronic disease, including hepatitis C, and has shown good validity and reliability.6,19–21 The SF-36 is a general health assessment tool consisting of 36 items with eight independent scales being derived from answers to these items, each one ranging from 0 to 100 and representing eight domains of health: physical functioning, role limitations -physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations- emotional and mental health. Moreover, through special algorithms, the domains can be grouped into two summary scales, physical and mental. Given the heterogeneity of instruments for assessing HRQOL, it is difficult and almost impossible to make comparisons among studies using different tools.

Literature searchPubMed database was searched from 1980 to October 2012 for articles in English, French, Portuguese and Spanish evaluating prospectively the change in HRQOL, comparing the scores before and after the antiviral therapy. The keywords were Hepatitis C or HCV or Parenterally Transmitted Non A, Non B Hepatitis or Chronic Hepatitis C or CHC and Quality of Life or QOL or Health Related Quality of Life or HR-QOL or Health Status or Status, Health or Level of Health or Health Level* and Therapy or Treatment or Immunotherap* or Interferon* or IFN. An asterisk after a term means that all terms that begin with that root were included in the search.

The authors defined selection criteria before beginning the search. There were three inclusion criteria:

- •

Clinical trials or observational studies, whose patients had been diagnosed as chronic-infected HCV and treated with interferon-α.

- •

Quality of life had to be evaluated prospectively using SF-36 with at least one measure at baseline and one measure six months (24 weeks) after the end of therapy.

- •

Quality of life scores had to be divided according to treatment response.

There was only one exclusion criterion:

- •

Studies evaluating specific populations affected by other diseases (e. g. hemophilia).

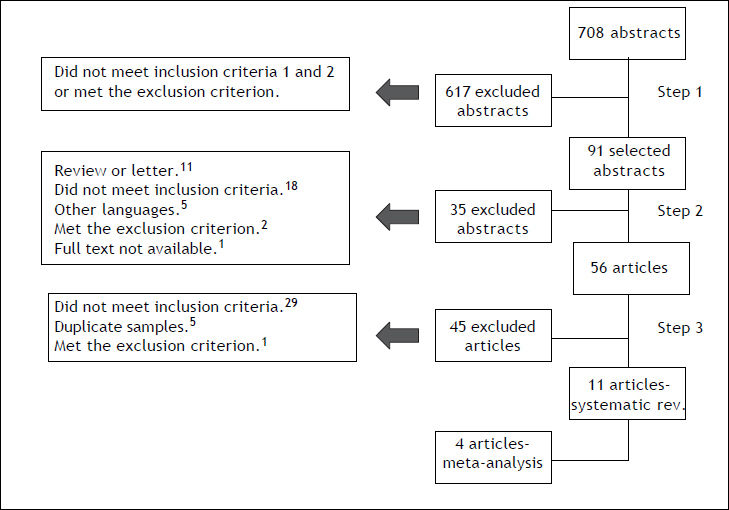

Three authors participated in the selection of articles through a three-step process:

- •

Step 1. Two authors (RDO and MMJ) selected articles, by analysis of the title and abstract. Articles were included if they met the inclusion criteria 1 and 2, and were excluded when they met the exclusion criterion. Any abstract lacking important information to fill the selection criteria was set aside for further investigation.

- •

Step 2. After independently selecting the abstracts, the authors selected, by consensus, which articles should have full text revision following the same selection criteria used in step 1. Any disagreements were resolved by a third author (LCQ).

- •

Step 3. Two authors (RDO and MMJ) independently reviewed each full text article previously selected. In this step, the articles were selected if they met all inclusion criteria (1, 2 and 3) and did not meet the exclusion criterion. If only the criterion 3 was not filled, the articles’ authors were contacted and the divided data were requested. Other authors from selected articles were also contacted and unpublished data, such as the mean and standard deviation, were solicited in order to build the meta-analysis. If these data could not be found or the articles were too different from the others, especially regarding the population studied and established treatment, they were excluded from the meta-analysis, but maintained in the systematic review. Any disagreements were resolved by a third author (LCQ).

Data was extracted by two authors independently (RDO and MMJ) using standard forms. Extracted data included sample size, features regarding the study sample (serological and virological status, previews treatment, histological stage of the disease, presence of comorbidities, ALT levels); design (randomization, awareness of treatment response before assessment of HRQOL) and outcomes (mean change of HRQOL and mean change difference between res-ponders and non-responders). Since some data were only available in graphics, the Engauge Digitalizer 4.1 software was used for data extraction.

Data analysisEight meta-analyses, one for each SF-36 domain, were conducted to estimate the difference between responders and non-responders of the mean change in scores at baseline and 24 weeks after the end of treatment, and the summary effect, p value and 95% interval confidence were obtained for each analysis using the random effects model. The Q test was used to assess statistical heterogeneity and the I2 statistic for measuring the degree of inconsistency.22 Egger’s test was used to evaluate the possibility of the occurrence of publication bias23 and, if necessary, the “Trim and Fill” method was applied to reestimate the values without bias.24 For all statistical analysis the significance was set at p < 0.05. The calculations and graphs were performed using the STATA 11.0 software.

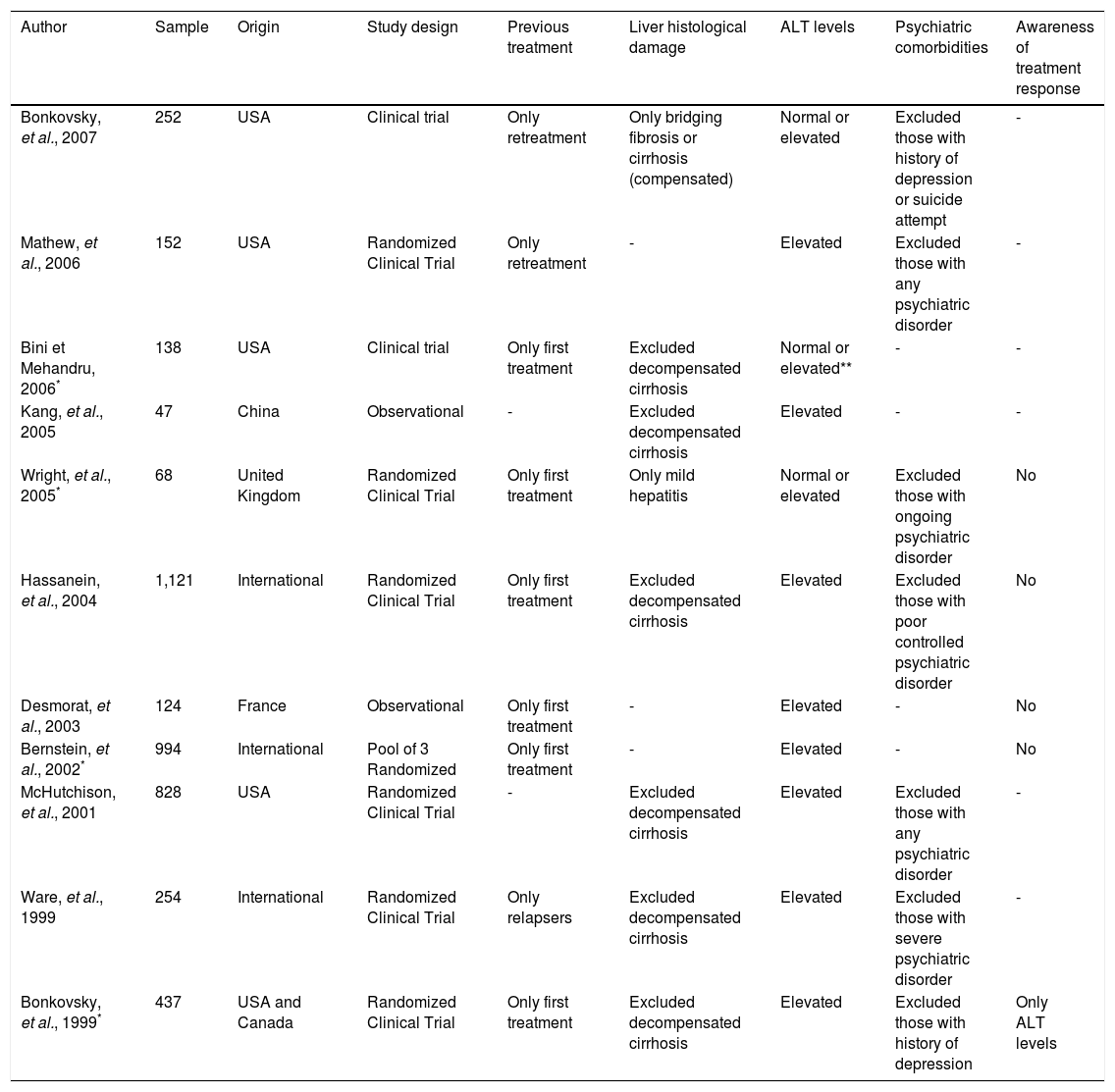

ResultsSystematic reviewA total of 708 abstracts were found searching the PubMed and the authors independently selected 91 abstracts for full text review. After comparison and discussion, 60 articles were selected for full text review. Finally, eleven articles were selected to compose the systematic review. The selection flow is presented in figure 1. Together, the selected articles evaluated 4,415 patients and the sample size ranged from 47 to 1,121 individuals. The articles were heterogeneous and their features are summarized in table 1.

Main characteristics of included studies.

| Author | Sample | Origin | Study design | Previous treatment | Liver histological damage | ALT levels | Psychiatric comorbidities | Awareness of treatment response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonkovsky, et al., 2007 | 252 | USA | Clinical trial | Only retreatment | Only bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis (compensated) | Normal or elevated | Excluded those with history of depression or suicide attempt | - |

| Mathew, et al., 2006 | 152 | USA | Randomized Clinical Trial | Only retreatment | - | Elevated | Excluded those with any psychiatric disorder | - |

| Bini et Mehandru, 2006* | 138 | USA | Clinical trial | Only first treatment | Excluded decompensated cirrhosis | Normal or elevated** | - | - |

| Kang, et al., 2005 | 47 | China | Observational | - | Excluded decompensated cirrhosis | Elevated | - | - |

| Wright, et al., 2005* | 68 | United Kingdom | Randomized Clinical Trial | Only first treatment | Only mild hepatitis | Normal or elevated | Excluded those with ongoing psychiatric disorder | No |

| Hassanein, et al., 2004 | 1,121 | International | Randomized Clinical Trial | Only first treatment | Excluded decompensated cirrhosis | Elevated | Excluded those with poor controlled psychiatric disorder | No |

| Desmorat, et al., 2003 | 124 | France | Observational | Only first treatment | - | Elevated | - | No |

| Bernstein, et al., 2002* | 994 | International | Pool of 3 Randomized | Only first treatment | - | Elevated | - | No |

| McHutchison, et al., 2001 | 828 | USA | Randomized Clinical Trial | - | Excluded decompensated cirrhosis | Elevated | Excluded those with any psychiatric disorder | - |

| Ware, et al., 1999 | 254 | International | Randomized Clinical Trial | Only relapsers | Excluded decompensated cirrhosis | Elevated | Excluded those with severe psychiatric disorder | - |

| Bonkovsky, et al., 1999* | 437 | USA and Canada | Randomized Clinical Trial | Only first treatment | Excluded decompensated cirrhosis | Elevated | Excluded those with history of depression | Only ALT levels |

In summary, nine out of eleven articles showed that patients who reached SVR to antiviral therapy had better outcomes than non-responders.6,7,20,25–30 Among the selected studies, six assessed specifically the mean change difference of HRQOL scores between responders and non-responders,20,25,27,30–32 one article did not find statistically significant difference between the two groups,32 and another found a better outcome for non-responders.31 The number of HRQOL domains presenting statistically different variations between the groups ranged from all to any domain. Physical functioning and general health were the domains that most often presented statistically different mean change variations.

Three papers evaluated only patients who had failed to respond to a previous treatment for HCV.6,25,32 Bonkovsky, et al.25 evaluated the change from baseline HRQOL in 252 patients with chronic hepatitis C and bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis and found that responders presented statistically significant improvements in four of eight HRQOL scores: role limitations -physical, general health, vitality and role limitations- emotional, while relapsers had a significant worsening in the physical functioning domain. The authors also found, by multivariate linear progression, that the major predictor of improvement in physical summary scores was achievement of SVR. Ware, et al.6 examined HRQOL changes in 254 previous relapsers retreated and found that responders presented statistically significant improvement in three of eight SF-36 domains (general health, vitality and social functioning), while non-responders only showed significant worsening in the general health domain. Mathew, et al.32 evaluated the change from baseline in 152 patients with CHC refractory to prior therapy undergoing retreatment. At 24 weeks after the end of treatment, the responders showed better scores in all domains, but none were statistically significant compared to baseline. Among non-responders, the scores at 24 weeks after the end of treatment were worse in four domains and better in the rest, but none were statistically different from baseline. There was also no statistical difference between the scores of responders compared to non-responders. Although there are few studies evaluating this population, there is evidence showing that the retreatment of CHC is followed by HRQOL improvements.

On the other hand, six studies evaluated the HRQOL changes in patients treating CHC for the first time.20,26,27,29–31 Of those, only one found a better outcome for non-responders; Wright, et al.31 evaluated the HRQOL change in 68 treatment-naïve patients with histological mild HCV infection receiving interferon-a and ribavirin. In conclusion, most of the studies that evaluated treatment-naïve patients found a better outcome for responders when compared to non-responders. Thus, in treatment naïve patients there is strong evidence showing improvements in HRQOL associated with SVR achievement.

Five articles analyzed the change in HRQOL before patients knew about their virologic status, as a measure to neutralize the effect of awareness of treatment response on the HRQOL scores.20,27,29–31 Four of these found a better outcome for responders,20,27,29,30 however Bonkovsky, et al.20 allowed the patients to know their ALT levels after treatment before the patients had the HRQOL evaluated.

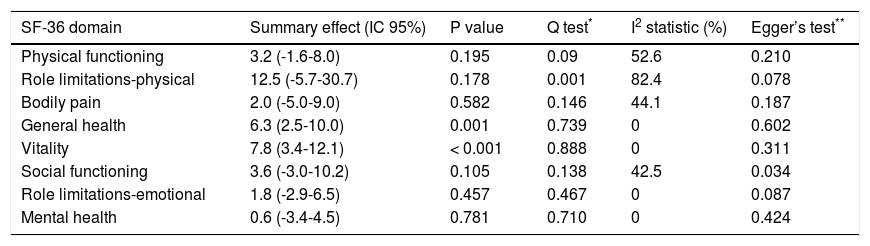

Meta-analysisAlthough eleven studies were selected in the systematic review, six did not present the mean change and the standard deviation, nor was it possible to obtain this data even when the authors were contacted.6,7,27–29,32 Also, one article was very different from the others, evaluating only patients with chronic hepatitis C and bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis who had failed to respond to a previous course of interferona.25 Thus, four studies were selected to create the meta-analysis.20,26,30,31 The summary effect, Q test, I2 statistic and Egger’s test results are presented in table 2 and the forest plots for each domain are presented in figures 2-9.

Meta-analysis results.

| SF-36 domain | Summary effect (IC 95%) | P value | Q test* | I2 statistic (%) | Egger’s test** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 3.2 (-1.6-8.0) | 0.195 | 0.09 | 52.6 | 0.210 |

| Role limitations-physical | 12.5 (-5.7-30.7) | 0.178 | 0.001 | 82.4 | 0.078 |

| Bodily pain | 2.0 (-5.0-9.0) | 0.582 | 0.146 | 44.1 | 0.187 |

| General health | 6.3 (2.5-10.0) | 0.001 | 0.739 | 0 | 0.602 |

| Vitality | 7.8 (3.4-12.1) | < 0.001 | 0.888 | 0 | 0.311 |

| Social functioning | 3.6 (-3.0-10.2) | 0.105 | 0.138 | 42.5 | 0.034 |

| Role limitations-emotional | 1.8 (-2.9-6.5) | 0.457 | 0.467 | 0 | 0.087 |

| Mental health | 0.6 (-3.4-4.5) | 0.781 | 0.710 | 0 | 0.424 |

CI 95%-95% confidence interval.

A. Forest plot for physical functioning. B. Forest plot for role limitations-physical domain. C. Forest plot for bodily pain domain. D. Forest plot for general health domain. E. Forest plot for vitality domain. F. Forest plot for social functioning domain. G. Forest plot for role limitations-emotional domain. H. Forest plot for mental health domain. Diamond represents summary mean change difference estimate; squares represent the mean change difference estimate of individual study; and horizontal lines represent 95% confidence interval.

Only one domain, role limitations -physical, showed statistically significant heterogeneity (p = 0.001) by the Q test. However, analyzing the inconsistency values as proposed by Higgins, et al.,22 four domains did not present any inconsistency (general health, vitality, role limitations, emotional and mental health)-, while three others presented moderate heterogeneity (physical functioning, bodily pain and social functioning). The only domain that showed evidence of publication bias was social functioning (p = 0.034) and the summary effect was recalculated using the Trim and Fill method.

Two domains, vitality and general health, showed statistically significant difference of mean change and are presented in figures 5 and 6. The domain general health showed mean change difference of 6.3 (CI 95% 2.5-10.0) and the domain vitality showed mean change difference of 7.8 (CI 95% 3.4-12.1). Other domains did not show significant difference of mean change.

DiscussionThe present paper shows that there is evidence indicating that the SVR is accompanied by a consistent improvement in HRQOL and is therefore not a mere incidental finding. Such evidence is present even in studies that assess only cirrhosis, previous non-responders, relapsers and patients in first treatment. Although the only work that evaluated patients with histologically mild hepatitis does not demonstrate a better outcome for responders,31 Bernstein, et al.30 evaluated separately a larger sample of patients without septal fibrosis or cirrhosis and found a more favorable outcome for responders than non-responders.

The domain vitality, for which a difference of 7.8 between responders and non-responders in mean change was estimated by meta-analysis, is derived from responses obtained in SF-36 questions that assess feelings of tiredness, exhaustion, vigor and energy. The considerable improvement shown by these individuals may be related to the end of fatigue reported by individuals chronically infected with HCV. Other studies have already shown that the SVR is related to improvement in fatigue.33 Furthermore, another systematic review has pointed to vitality as the most relevant domain for these patients and set the value of 4.2 as Minimum Clinically Important Difference (MCID), namely, the smallest change in HRQOL that may be important for these patients.34 The mean change difference for vitality, found in this study, higher than the value determined as MCID, indicates that the achievement of SVR is accompanied by clinically important changes in HRQOL for patients with CHC. It is worth noting that each SF-36 domain represents a different aspect of HRQOL and thus the number of domains which presented a statistically significant mean change does not carry too much importance, unlike the meaning each domain has for HRQOL.

Most studies showed considerable loss of individuals during follow-up, either because they discontinued antiviral therapy early or did not answer the SF-36 after treatment. These patients may represent both individuals who not obtaining an appreciable improvement in HRQOL, became frustrated and dropped out, and those who had such a satisfying response that they did not find it necessary to return.

However, this study has some limitations. The results cannot be applied to people with mental disorders, since seven studies, among those included in the systematic review, excluded from their sample patients with psychiatric disorders. Although this exclusion guarantees a higher quality to the trials, patients with psychiatric disorders may have a different change pattern in HRQOL associated with the achievement of SVR and, given the existence of psychiatric implications of CHC, whether associated with infection or antiviral treatment, there may be some distortion in the final outcome of these studies. At the same time, only five studies20,27,29–31 have some concern about how the subjective effect of knowledge of treatment response could resonate on the HRQOL of these individuals. Nevertheless, four of five studies that evaluated blindly HRQOL showed better results in responders after therapy, as opposed to non-responders.20,27,29,30

The studies included in meta-analysis showed various degrees of clinical and statistical heterogeneity, despite some characteristics that make them seemingly heterogeneous, such as degree of histological impairment of the liver, are not associated with a reduction in HRQOL in patients with hepatitis C. On the other hand, adoption of the random effects model reduces the impairment caused by high heterogeneity in some areas.

ConclusionThere is strong scientific evidence indicating that SVR is associated with an improvement in HRQOL, in different groups of CHC patients. Furthermore, most studies in which patients were unaware of the response to treatment showed that responders have a better outcome than non-responders, indicating that only the knowledge of SVR achievement could not explain the difference in HRQOL between the two groups. Through meta-analysis, the authors demonstrated that patients with SVR to antiviral therapy have a statistically significant improvement in domains of general health and vitality, after antiviral therapy, which can be considered clinically relevant.

Abbreviations- •

HCV: hepatitis C virus.

- •

HRQOL: health-related quality of life.

- •

SVR: sustained virologic response.

- •

CHC: chronic hepatitis C.

- •

ALT: alanine transaminase.

- •

HALT-C: hepatitis C antiviral long-term treatment against cirrhosis.

- •

MCID: minimum clinically important difference.

This project was supported by the National Council of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq): [474869/2010-5] - Edital Universal MCT/ CNPq 14/2010 and by the Institutional Program of Scientific Initiation Scholarship (PIBIC).

AcknowledgementsWe are grateful to Dr. Angela Miranda-Scippa and Dr. Ana Thereza Britto for their technical assistance. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.