Hepatic encephalopathy is an alteration of the central nervous system as a result of hepatic insufficiency after the exclusion of other known causes, and occurs in patients with cirrhosis, acute hepatic failure or portacaval shunts.1 It is characterized by a range of different neuropsychiatric disturbances that can include impairment of the sleep-wake cycle, cognition, memory, consciousness, personality changes, motorsensory abnormalities, stupor and coma.1

Minimal hepatic encephalopathy (MHE) is considered to be the first stage of this clinical course. It is defined as HE without symptoms on clinical/neurological examination but with mild cognitive symptoms and attention deficits that can be characterized by response disinhibition, and with impairments to working memory and visuomotor coordination.2–4 As suggested by Bajaj, et al., these symptoms are considered to reduce the safety2 and quality of life (QOL) of patients with cirrhosis3 and are considered to be a preclinical stage of overt HE.2,3

MHE has a high prevalence of 22 to 80% in patients with liver cirrhosis.2,4 It is a diagnosis that all physicians should be aware of, but there is a fine line between normal and pathological, which can be modified by factors such as education or other comorbidities. At present, many questions remain regarding patients with MHE. Should they receive treatment? What type of treatment should they receive? How long should they receive treatment? Are there preventive measures for these patients?

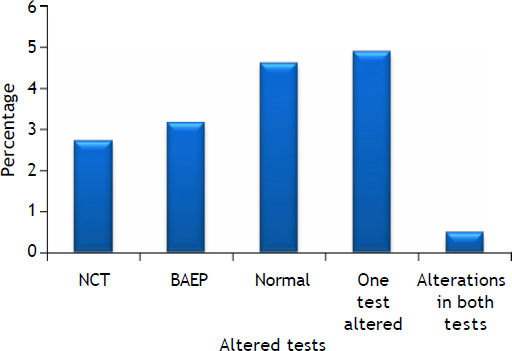

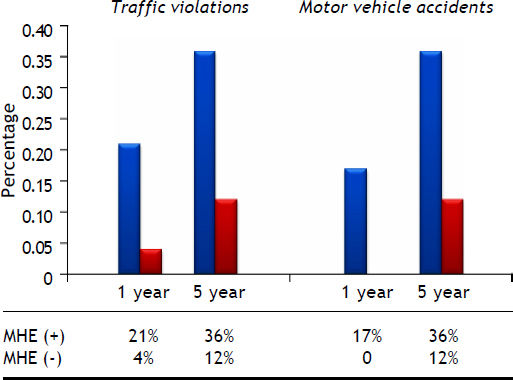

With regard to the first question, several studies have shown a positive effect of treatment on cognitive abilities (Figure 1), quality of life,5 and driving ability (Figure 2),6 but its effect on patients’ ability to work or their risk of falling remains unproven.4 A summary of reports of treatment in MHE and its impact on psychometric variables is presented in table 1, which suggests that treatment should be considered.

Altered test results present in cirrhotic patients. Modified from reference 13. A combination of neurophysiologi-cal tests was used for screening. Cirrhotic patients exhibit selective deficits in the number connection test (NCT), brainstem auditory evoked potentials (BAEP) test or both tests.

Driving history in patients with cirrhosis. Modified from reference 14. The graph shows that cirrhotic patients have a higher self-reported occurrence of violations and accidents compared with controls, so that MHE is considered a strong predictor for violations and accidents in a five years-follow up. MHE, minimal hepatic encephalopathy.

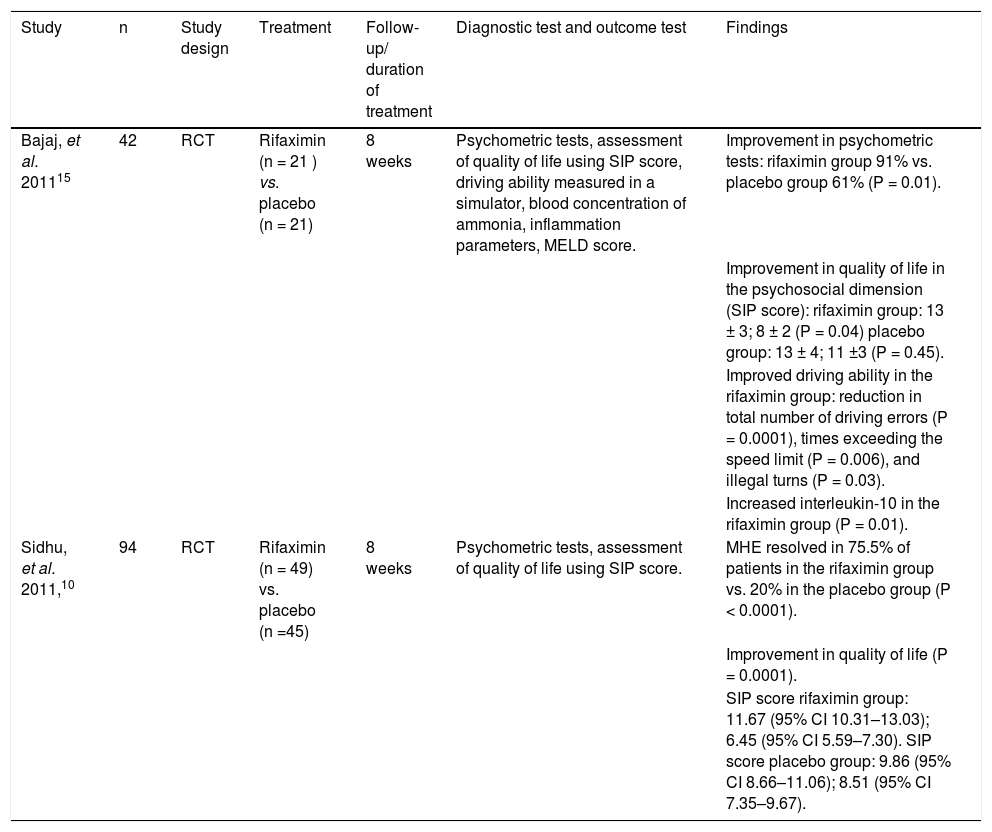

Treatment of MHE.

| Study | n | Study design | Treatment | Follow-up/ duration of treatment | Diagnostic test and outcome test | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bajaj, et al. 201115 | 42 | RCT | Rifaximin (n = 21 ) vs. placebo (n = 21) | 8 weeks | Psychometric tests, assessment of quality of life using SIP score, driving ability measured in a simulator, blood concentration of ammonia, inflammation parameters, MELD score. | Improvement in psychometric tests: rifaximin group 91% vs. placebo group 61% (P = 0.01). |

| Improvement in quality of life in the psychosocial dimension (SIP score): rifaximin group: 13 ± 3; 8 ± 2 (P = 0.04) placebo group: 13 ± 4; 11 ±3 (P = 0.45). | ||||||

| Improved driving ability in the rifaximin group: reduction in total number of driving errors (P = 0.0001), times exceeding the speed limit (P = 0.006), and illegal turns (P = 0.03). | ||||||

| Increased interleukin-10 in the rifaximin group (P = 0.01). | ||||||

| Sidhu, et al. 2011,10 | 94 | RCT | Rifaximin (n = 49) vs. placebo (n =45) | 8 weeks | Psychometric tests, assessment of quality of life using SIP score. | MHE resolved in 75.5% of patients in the rifaximin group vs. 20% in the placebo group (P < 0.0001). |

| Improvement in quality of life (P = 0.0001). | ||||||

| SIP score rifaximin group: 11.67 (95% CI 10.31–13.03); 6.45 (95% CI 5.59–7.30). SIP score placebo group: 9.86 (95% CI 8.66–11.06); 8.51 (95% CI 7.35–9.67). |

RCT: randomized controlled trial. SIP: sickness impact profile (questionnaire assessing health-related quality of life; the lower the value, the better the quality of life). MHE: minimal hepatic encephalopathy. MELD: model for end-stage liver disease. CI: confidence interval.

The next question that arises is the type of treatment that patients with MHE should receive. Many approaches have been proposed, including lactulose, rifaximin and probiotics, minimizing dietary protein, branched-chain amino acids,7 and L-ornithine L-as-partate (LOLA).5

Nonabsorbable disaccharides reduce the synthesis and uptake of ammonia by lowering the pH of the colon and also reduce the uptake of glutamine from the gut.4 Treatment of MHE with lactulose resulted in an absolute risk reduction of 21.7% and the number needed to treat was 4.6. Different studies have compared the use of lactulose with placebo or no intervention. In a study by Sharma, et al., of patients with MHE at baseline, HE developed in six patients treated with lactulose and 15 not treated with lactulose, with an absolute risk reduction of 22.9% and a number needed to treat of 4.3. Another study by Luo, et al.8 compared lactulose with placebo or no intervention. This study showed beneficial effects for patients with MHE, and there was a reduction in the risk of no improvement in neuropsychological tests [relative risk (RR): 0.52, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.44–0.62, P < 0.00001], the time required for the completion of the number connection test (weighted mean difference (WMD): −26.95, 95% CI: − 37.81 to −16.10, P < 0.00001), and the mean number of abnormal neuropsychological tests (WMD: −1.76, 95% CI: −1.96 to −1.56, P < 0.00001). The usual oral dose of lactulose is 15–30 mL twice daily to achieve a soft stool several times a day. Even though different durations of treatment have been tested in different randomized clinical trials (RCT), we consider that a course of treatment should continue for at least 3 to 6 months.

Another approach for treatment of MHE is the use of antibiotics, which aims to reduce the production of ammonia in the gut. Neomycin and macrolides have been used, but because of their toxicity new drugs are under study. Rifaximin is an antibiotic that shows minimal absorption in the gut and has been licensed in the United States of America since 2010 for the treatment of HE.4 Bass, et al.9 were able to show in a large study that long-term therapy with rifaximin plus lactulose in patients with a history of HE gave better protection against renewed episodic HE than did the placebo treatment (hazard ratio with rifaximin: 0.42; 95% CI 0.28–0.64; P < 0.001). When the effects in patients with MHE were analyzed by Sidhu, et al., more patients showed remission of MHE after treatment for 8 weeks with a dose of 1,200 mg/day of rifaximin than in the placebo group (75.5 vs. 20%; P < 0.0001).10

Probiotics have also been used in the treatment of HE. They reduce ammonia in the portal blood by decreasing bacterial urease activity in the intestinal lumen, decrease ammonia absorption by decreasing intestinal pH and improve the nutritional status of gut epithelium. Overall, these effects decrease intestinal permeability, inflammation and oxidative stress in hepatocytes, which leads to increased hepatic clearance of ammonia.5 Yogurt has been proposed as a probiotic treatment as it is a palatable food, is widely available and does not require prescription, all of which favor long-term adherence to treatment. However, the reported studies used different concentrations of probiotics. Complete reversal of MHE was achieved only in those patients who consumed yogurt (71%, P = 0.003) and was associated with an improvement in psychometric test results.5 In a random effects meta-analysis performed by Holte, et al., probiotics/synbiotics vs. placebo or lactulose improved HE (51 vs. 31%, RR = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.05–1.86; I2 = 5%, P = 0.02), so perhaps this line of treatment could have potential.11

Finally, we consider the question of prophylaxis. Lactulose has been proposed for primary prophylaxis of MHE.12 In the study by Sharma, et al. of 250 patients screened, 120 (48%) met the inclusion criteria and were randomized to lactulose (n = 60) or no lactulose (n = 60). Twenty (19%) of 105 patients followed for 12 months developed an episode of overt HE. Six (11%) of 60 in the lactulose group and 15 (28%) of 50 in the no lactulose group (P = 0.02) developed overt HE.

We conclude that in patients with MHE a course of treatment is warranted to improve their quality of life. We are conscious that more RCT and metaanalyses are needed to identify the optimal treatment, as some of the reported trials do not separate the treatment of MHE from treatment of all HE. Several treatment alternatives have been proposed (Table 2), from just a few days duration up to 3 or 6 months, and we consider that at least 6 months treatment with lactulose or probiotics should be initiated once a diagnosis has been made, and a course of lactulose as prophylaxis needs to be considered. In summary, we encourage new studies and novel approaches to this increasing pathology, though rigorous evaluation is still needed.

Treatment for hepatic encephalopathy.

| Study | n | Study design | Treatment | Duration of treatment | Outcome | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eltawil, et al. 201216 | 565 | RCT | Rifaximin (n = 184) vs. non absorbable disaccharides (n = 165). | 7 days-6 months | Effectiveness | Both groups experienced either full resolution of HE or clinical improvement (OR = 1.92, 95% CI 0.79–4.68, Ρ = 0.15). |

| Rifaximin (n = 68) vs. other antibiotics (neomycin or paromomycin n = 60). | Rifaximin had similar effectiveness to neomycin or paromomycin (OR = 2.77, 95% CI 0.35–21.83, Ρ = 0.21). | |||||

| The results of the combined analysis with both groups of patients receiving antibiotics or disaccharides showed a trend that favored the use of rifaximin (OR = 1.96, 95% CI 0.94–4.08, Ρ = 0.07). | ||||||

| Rifaximin (n = 980) vs. control group (n = 988). | Adverse events | Rifaximin gave less risk of suffering from diarrhea (OR = 0.20, 95% CI 0.04–0.92, Ρ = 0.04) although the rate of abdominal pain nausea/anorexia/weight loss was similar between the two groups (P = 0.40, Ρ = 0.06, respectively). | ||||

| Combined analysis of all the adverse events favored the use of rifaximin (fewer side effects) (OR = 0.27, 95% CI 0.12–0.59, Ρ = 0.001). | ||||||

| Rifaximin (n = 138) vs. nonadsorbable disaccharides (n = 128). | Serum ammonia level | Participants who received rifaximin had lower serum ammonia levels in comparison with patients who received nonadsorbable disaccharides although the difference did not reach significance (P = 0.30). | ||||

| Rifaximin (n = 60) vs. other oral antibiotics (n = 60) | ||||||

| Controls (n = 176) vs. rifaximin (n = 181). | Similar results were observed when comparing rifaximin vs. other oral antibiotics (P = 0.33) although the differences were not significant. When compared with all the controls, patients treated with rifaximin had an overall lower mean serum ammonia level (WMD = −10.65, 95% CI −23.46–2.17, Ρ = 0.10). | |||||

| Holte, et al. 201217 | 393 | RCT | Probiotics/synbiotics vs. placebo or lactulose (87/171 vs. 50/162). | 10 days-3 months | Improvement in HE | A random effects meta-analysis of these trials revealed that probiotics/synbiotics vs. placebo or lactulose improved HE (51% vs. 31%) RR = 1.40, 95% CI 1.05–1.86; I2 = 5%, Ρ = 0.02). |

| Six trials reported on deterioration of HE or progression from MHE to overt HE. Overall, there was no apparent effect of probiotics/synbiotics on these outcomes (5/171 [3%] vs. 12/162 [7%]; RR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.20–1.34; I2 = 0%). | ||||||

| Probiotics/synbiotics vs. placebo or lactulose (87/171 vs. 50/162). | Serum ammonia level | Probiotics decreased arterial ammonia (WMD = 15.95; 95% CI 26.72–3.28; I2 = 68%, Ρ = 0.01, three trials), but not venous ammonia (WMD = 5.23; 95% CI 21.77–11.30; I2 = 89%, Ρ = 0.54, four trials). | ||||

| Probiotics/synbiotics vs. placebo groups (4/91 vs. 12/89). | Adverse events | Overall adverse events were reported in four trials with no difference between probiotics/synbiotics and placebo groups (4/91 [4%] vs. 12/89 [13%]; RR = 0.32, 95% CI 0.04–2.57; I2 = 59%). | ||||

| Bai, et al. 201318 | 646 | RCT | LOLA (n = 160) vs. placebo/no intervention control (n = 110) (HE). | 5 days-3 months | Improvement of HE | The percent of patients with improved HE was higher in the LOLA group when both MHE and OHE patients were included (68% vs. 47%), RR = 1.49 (95% CI 1.1–2.01). |

| According to date published (before 2000 vs. after 2000). The RR values were 1.89 (95% CI 1.32–2.70, fixed-effect model) and 1.18 (95% CI 1.05–1.33, fixed-effect model). | ||||||

| LOLA was more effective than the no intervention control in both the subgroups with treatment duration of more than 10 days vs. treatment duration of less than 10 days. | ||||||

| LOLA (n = 130) vs. placebo/ no intervention control (n = 97) (OHE). | Improvement was more frequently observed in the LOLA group vs. placebo/no intervention control group (84 vs. 65%, RR 1.33, 95% CI 1.04-1.69). | |||||

| LOLA (n = 30) vs. placebo/no intervention control (n = 13) (MHE) | MHE patients in the LOLA group had higher rates of improvement of HE than those in the placebo/no-intervention groups (36 vs. 15%), RR = 2.25 (95% CI 1.33-3.82, fixed-effect model, heterogeneity test: Ρ = 0.64). In all of the subgroup analyses, LOLA was more effective than the no intervention control. | |||||

| LOLA (n = 160) vs. placebo/no intervention control (n = 110) (HE). | Adverse effects | The incidences of adverse events were 11% for both LOLA and the placebo/no intervention control (RR = 1.15, 95% CI 0.65-2.04, heterogeneity test: Ρ = 0.13). | ||||

| LOLA (n = 40) vs. lactulose (n = 40). | Improvement of HE, reduction of serum ammonia, mortality | Treatment was not significantly different in the improvement of HE, the reduction of serum ammonia or the mortality. The pooled RR of the improvement of HE was 0.88 (95% CI 0.57–1.35, 12 = 49%, heterogeneity test: Ρ = 0.16). |

RCT: randomized clinical trial. LOLA: L-ornithine-L-aspartate. HE: hepatic encephalopathy. MHE: minimal HE. OHE: overt HE. CI: confidence interval.

- •

CI: confidence interval.

- •

HE: hepatic encephalopathy.

- •

LOLA: L-ornithine L-aspartate.

- •

MHE: minimal hepatic encephalopathy.

- •

QOL: quality of life.

- •

RCT: randomized clinical trials.

- •

RR: relative risk.

- •

WMD: weighted mean difference.