Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) indication of liver transplant (LT) has increased recently, whereas alcoholic cirrhosis remains a major indication for LT. To characterize NASH-related cases and to compare the post-transplant outcome of these two conditions represents our major objective.

Material and methodsPatients undergoing LT for NASH between 1997 and 2016 were retrieved. Those transplanted between 1997 and 2006 were compared to an “age and LT date” matched group of patients transplanted for alcoholic cirrhosis (ratio 1:2). Baseline features and medium-term outcome measures were compared.

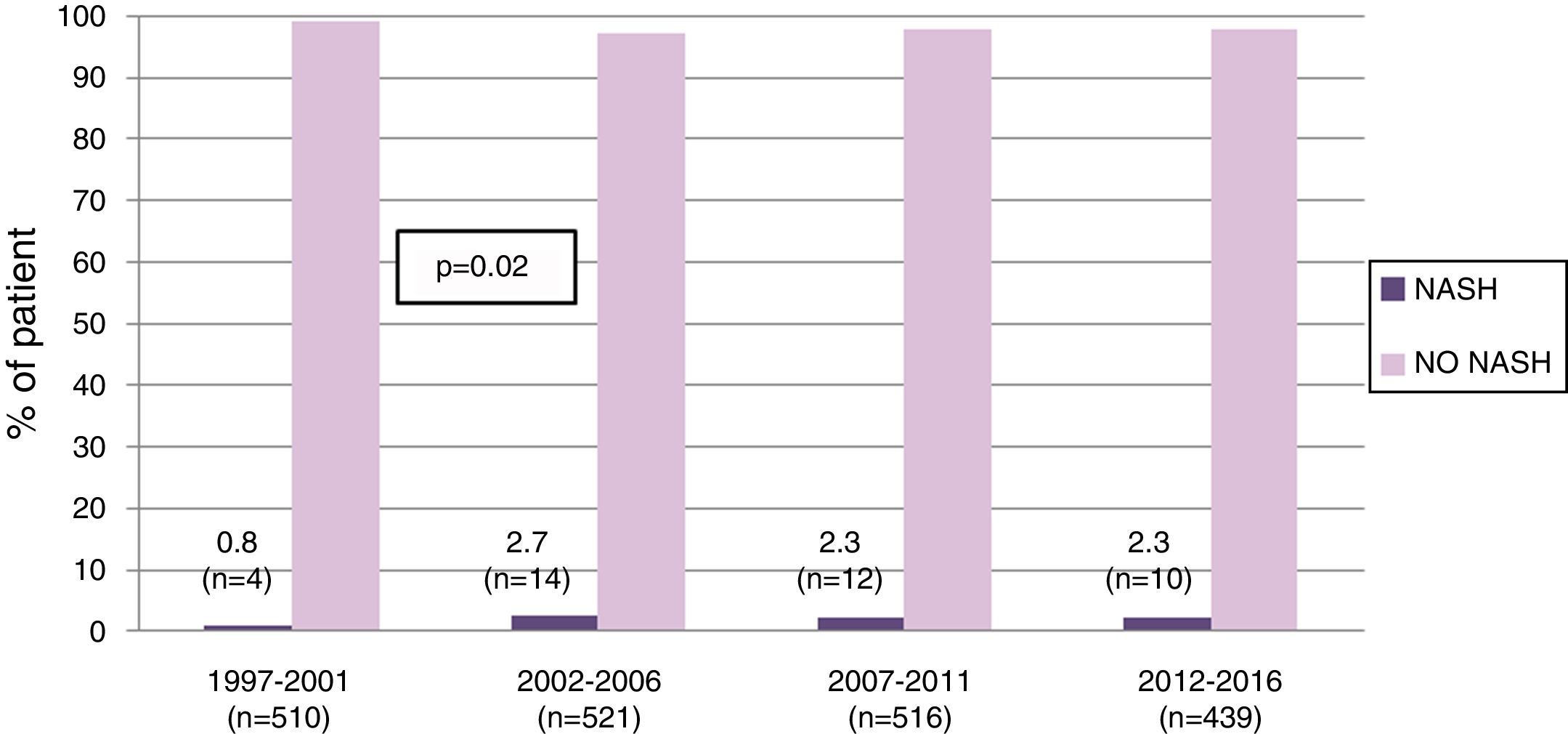

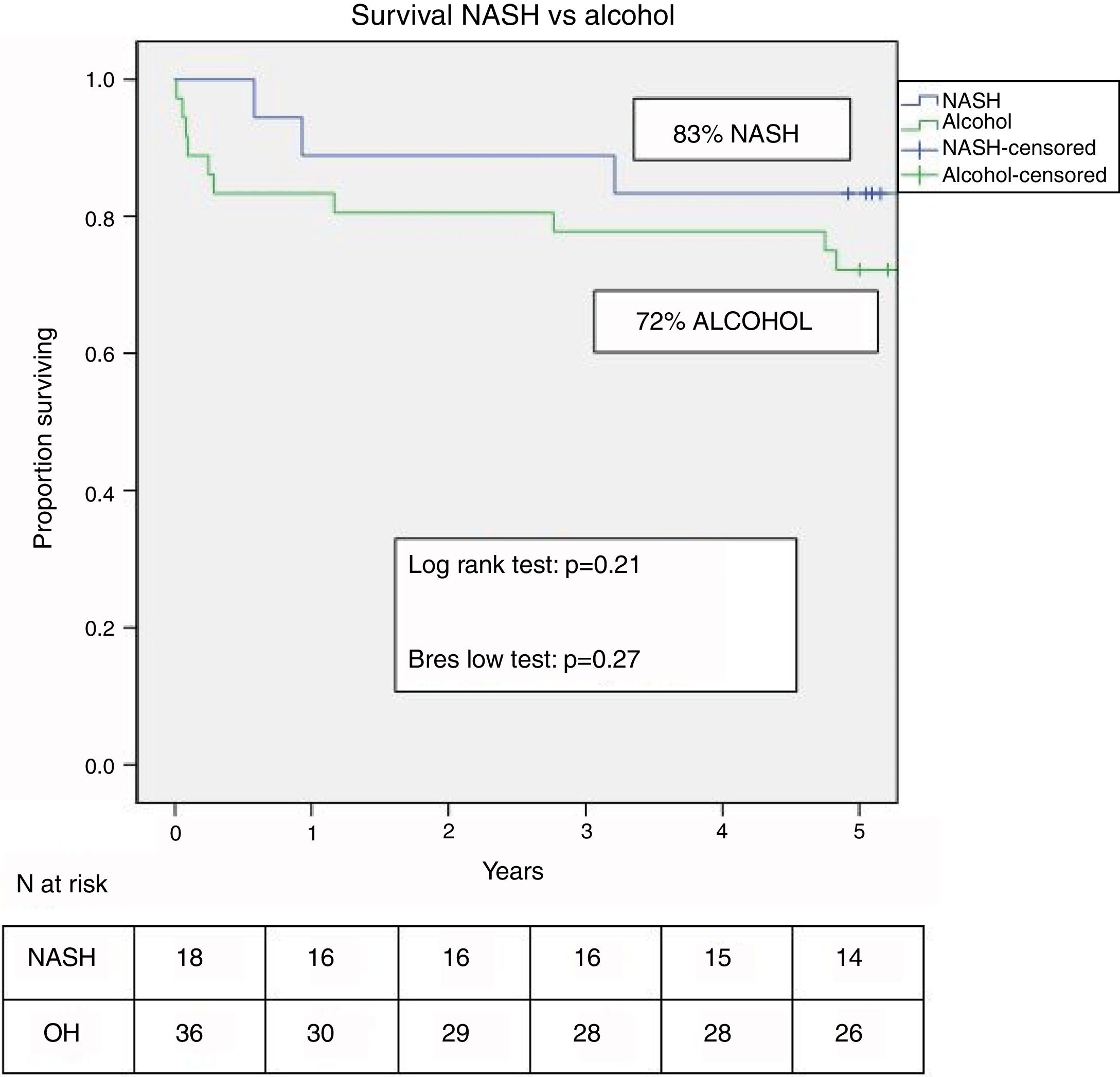

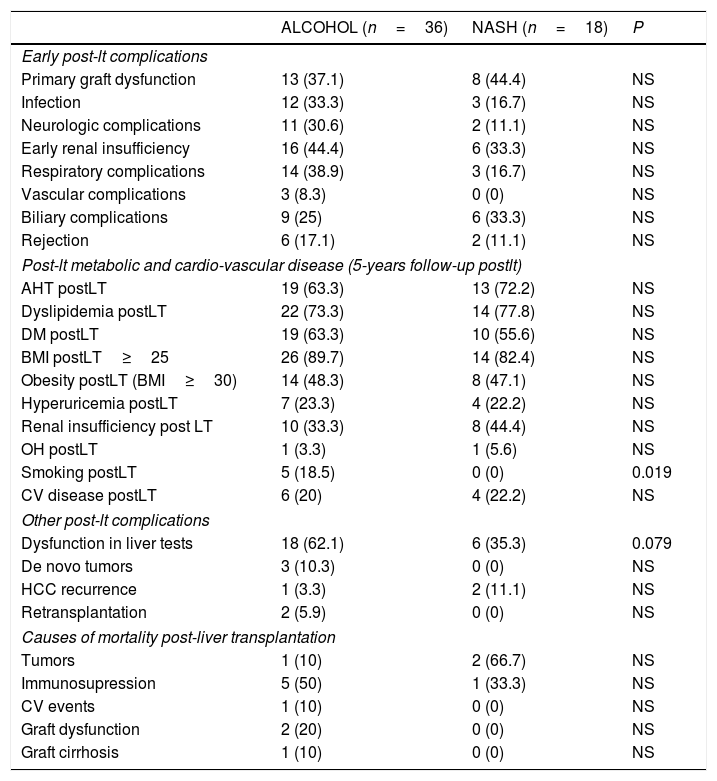

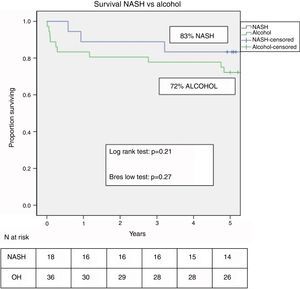

ResultsOf 1986 LT performed between 1997 and 2016, 40 (2%) were labeled as NASH-related indications. NASH-related cases increased initially (from 0.8% in 1997–2001 to 2.7% in 2002–2006) but remained stable in subsequent years (2.3%). Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) prevalence was greater in NASH-vs alcohol-related cirrhosis (40% vs 3%, p=0.001). The incidence of overweight, obesity, arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, hyperuricemia, renal insufficiency and cardiovascular (CV) disease was similar in both groups at 5 years post-LT. Five-year survival was higher in NASH but without reaching statistical significance (83% vs 72%, p=0.21). The main cause of mortality in NASH-LT patients was HCC recurrence.

ConclusionMost previously considered cryptogenic cases are actually NASH-cirrhosis. While the incidence of this indication is increasing in many countries, it has remained relatively stable in our Unit, the largest LT center in Spain. HCC is common in these patients and represents a main cause of post-transplant mortality. Metabolic complications, CV-related disease and 5-yr survival do not differ in patients transplanted for NASH vs alcohol.

A significant proportion of cryptogenic cirrhosis (CC) cases are due to undiagnosed autoimmune hepatitis or undiagnosed fatty liver disease [1–7]. Although non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)-related cirrhosis is still not the first indication of LT in western countries [1,8,9], its prevalence has substantially increased in recent years, mostly due to the high prevalence of diabetes and obesity [3,4]. Indeed, in the United States, the percentage of patients undergoing a liver transplant for NASH increased from 1.2% in 2001 to 9.7% in 2009 becoming in 2017 the second most common indication for liver transplantation (LT) in that country [10]. A correct diagnosis of NASH requires a careful exclusion of other liver diseases; daily alcohol consumption should not be higher than 20g in women or 30g in men, and hepatotoxins should be excluded. Risk factors associated with NASH include abdominal obesity, arterial hypertension (AHT), diabetes, insulin resistance and dyslipidemia [11,12]. Like many other diseases leading to LT, NASH may recur after LT. In addition, known risk factors associated with NASH are very common post-transplantation, particularly diabetes, AHT, obesity and dyslipidemia. Short and medium-term post-transplant outcome however does not differ from that of other etiologies [13–15].

On the other hand, alcoholic cirrhosis is a major indication for LT in most registries. Post-transplant outcome is similar or even better than that obtained by other indications such as hepatitis C virus (HCV) cirrhosis [16]. While recurrence of alcohol intake is common, significant graft damage is rare [17–19]. In these patients, cardiovascular (CV) risk factors including tobacco use are also common after LT and CV events appear to occur more frequently than in other indications [17,20].

Given the similarities in the physiopathology and pathology of alcohol and NASH-related liver diseases and the frequent coexistence of CV risk factors in both conditions, we decided to compare their outcome post-liver transplantation. We had two main hypotheses to test; first that, in our center, and as previously noted in other studies [10,21–23], most patients transplanted in the past for CC were in fact NASH-related cases; and second, that post-transplant survival and development of CV events are similar in these two groups. Our specific aims were: (i) to better characterize patients with CC and to identify those that could be defined as NASH-related cases; (ii) to compare the mid-long term survival of NASH cases to that obtained by those transplanted for alcoholic cirrhosis; (iii) to determine and compare the incidence of metabolic complications, CV events and de novo tumors in these two groups.

2Material and methodsThis is a prospective chart and database review of a retrospective cohort of patients who had undergone liver transplantation (from cadaveric donors) at our center between January 1997 and December 2016 for CC who fulfilled the criteria for NASH-related disease. Once this cohort was selected, we performed a case control study {ratio 1:2; taking into account age (±10 yrs) and LT date (±6 months)} comparing the outcome of the CC/NASH related cases to control patients transplanted during the period 1997–2006 for alcohol related liver disease. Criteria to define a CC as a NASH-related indication were: pre-LT presence of at least two features associated with fatty liver disease, including at least one major risk factor, being overweight and/or obese, or having diabetes, that should be present together with AHT, dyslipidemia, or >5% steatosis in a previous liver biopsy or in the explant in the absence of significant consumption of alcohol [1,3–5,7].

Clinical and laboratory variables were retrieved from the pre and post-transplant follow up until the patient death or the last outpatient visit. These variables included demographics (age and gender), recipient pre-LT variables (LT indication, type of liver decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma-HCC, Child–Pugh score, model for end-stage liver disease – MELD – score, tobacco use, body mass index – BMI, AHT, diabetes, overweight, obesity, dyslipidemia, CV events, histology activity index and steatosis on the explant), donor-related variables (age, gender, steatosis, BMI, AHT, diabetes, days in the intensive care unit) and post-LT variables (primary graft dysfunction, arterial and/or biliary complications, type of immunosuppression, rejection episodes, alcohol and tobacco use, AHT, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hyperuricemia, renal insufficiency, CV events, de novo tumors, laboratory parameters, ultrasonographic steatosis, non alcoholic fatty liver disease – NAFLD – fibrosis score, histologic findings when available). The definition of each risk factor was as follows: (i) overweight and obesity: BMI≥25 or 30kg/m2, respectively [24]; (ii) post-LT diabetes (World Health Organization – WHO – criteria): basal glycaemia>126mg/dl or>200 anytime during the day, in at least 3 consecutive measurements, and/or the need of anti-diabetic therapy [25]; (iii) post-LT AHT (WHO criteria): systolic blood pressure of ≥140mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure of ≥90mmHg in at least 3 consecutive measurements and/or the need of medication [26]; (iv) post-LT dyslipidemia: total cholesterol>250mg/dl and/or triglycerides>150mg/dl, in at least 3 consecutive measurements and/or the need of medication [27]; (v) CV event: ischemic cardiomyopathy, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease (vi) chronic renal insufficiency: creatinine levels>1.5mg/dl in at least 3 consecutive measurements for at least 30 days. This cut-off was chosen in order to be able to compare the data with that of prior published studies [28,29]; (vii) alcoholic recidivism: any post-LT alcohol intake detected by direct interview of the patient and/or his/her family; (viii) liver test (transaminases, gammaglutamyl-transpeptidase – GGT, phosphatase alkaline, bilirubin) abnormalities (above the upper limit of normality) maintained during more than 6 months; (ix) NAFLD fibrosis score: non-invasive scoring system based on several variables (diabetes, age, aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase – AST/ALT, platelet count, BMI, albumin) to estimate the amount of liver fibrosis.

Given the retrospective nature of the data collected, the ethical committee did not consider necessary to undergo a full Local Ethical Committee approval. Indeed, all patients transplanted at our center sign a consent form to use their data (anonymously and in accordance with the organic law on data protection) in future analyses to audit the results of transplantation.

2.1Statistical analysis:Qualitative variables are summarized as ratios and compared using the X2-test while quantitative variables are described as means (±SD) or median and range and compared through the T Student or Mann–Whitney test. Survival curves are depicted as Kaplan–Meier events and compared with the log-rank. A p value≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3Results3.1Patient populationFrom 1997 to 2016, 1986 LT were performed in our center in adults. Of these, 40 (2%) were labeled as NASH-related indications. While the proportion of NASH-related cases increased from 0.8% in 1997–2001 to 2.7% in those transplanted between 2002 and 2006 (p=0.02), it remained stable thereafter (Fig. 1).

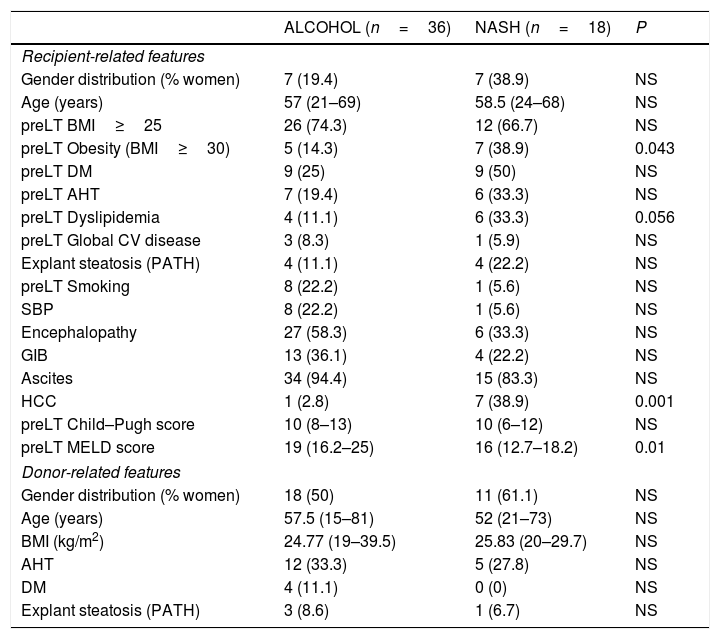

Of 1031 LT performed before 2007, 25 (2.4%) were labeled as CC. After reviewing these cases, 18 (72%) corresponded to NASH patients and were the focus of our study. The control group consisted of 36 patients transplanted for alcoholic cirrhosis matched by age and LT date. The mean follow-up was 4.1 years. Baseline features of the two groups are summarized in Table 1. Tobacco use was more common in the alcoholic cirrhotic patients; in contrast, and as expected, CV risk factors such as diabetes, AHT, obesity and dyslipidemia were more common in NASH patients. HCC was more common in NASH vs alcohol patients (39% vs 3%; p=0.001). Two cases were incidental tumors found in the explant, two were outside Milan criteria and all the remaining tumors, including that developing in one alcoholic-cirrhotic patient were within Milan criteria. The MELD score was significantly higher in the alcohol-cirrhosis group.

Comparison of NASH and alcohol-related patients: recipient and donor related features.

| ALCOHOL (n=36) | NASH (n=18) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient-related features | |||

| Gender distribution (% women) | 7 (19.4) | 7 (38.9) | NS |

| Age (years) | 57 (21–69) | 58.5 (24–68) | NS |

| preLT BMI≥25 | 26 (74.3) | 12 (66.7) | NS |

| preLT Obesity (BMI≥30) | 5 (14.3) | 7 (38.9) | 0.043 |

| preLT DM | 9 (25) | 9 (50) | NS |

| preLT AHT | 7 (19.4) | 6 (33.3) | NS |

| preLT Dyslipidemia | 4 (11.1) | 6 (33.3) | 0.056 |

| preLT Global CV disease | 3 (8.3) | 1 (5.9) | NS |

| Explant steatosis (PATH) | 4 (11.1) | 4 (22.2) | NS |

| preLT Smoking | 8 (22.2) | 1 (5.6) | NS |

| SBP | 8 (22.2) | 1 (5.6) | NS |

| Encephalopathy | 27 (58.3) | 6 (33.3) | NS |

| GIB | 13 (36.1) | 4 (22.2) | NS |

| Ascites | 34 (94.4) | 15 (83.3) | NS |

| HCC | 1 (2.8) | 7 (38.9) | 0.001 |

| preLT Child–Pugh score | 10 (8–13) | 10 (6–12) | NS |

| preLT MELD score | 19 (16.2–25) | 16 (12.7–18.2) | 0.01 |

| Donor-related features | |||

| Gender distribution (% women) | 18 (50) | 11 (61.1) | NS |

| Age (years) | 57.5 (15–81) | 52 (21–73) | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.77 (19–39.5) | 25.83 (20–29.7) | NS |

| AHT | 12 (33.3) | 5 (27.8) | NS |

| DM | 4 (11.1) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Explant steatosis (PATH) | 3 (8.6) | 1 (6.7) | NS |

Results: n (%); median (range 25–75).

NS: not significant.

AHT: arterial hypertension; BMI: body mass index; CV disease: cardiovascular disease; DM: diabetes mellitus; GIB: gastrointestinal bleeding; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; NASH: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; OH: alcohol; PATH: pathology; preLT: liver pretransplant; SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

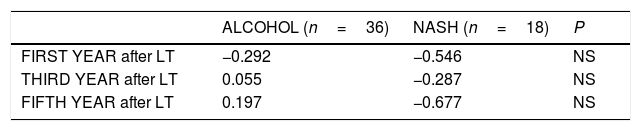

Donor related variables did not differ between the 2 groups (Table 1). In the early post-transplant period (before discharge) no significant differences were found between the 2 groups, except for early respiratory and neurologic post-LT complications which were more common in the alcoholic group but without reaching statistical significance (Table 2). There were also no significant differences between groups in relation to immunosuppression at discharge (suppl material, table A) or at end of follow up (suppl material, table B).

Post-LT complications and mortality in NASH vs alcohol related groups.

| ALCOHOL (n=36) | NASH (n=18) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early post-lt complications | |||

| Primary graft dysfunction | 13 (37.1) | 8 (44.4) | NS |

| Infection | 12 (33.3) | 3 (16.7) | NS |

| Neurologic complications | 11 (30.6) | 2 (11.1) | NS |

| Early renal insufficiency | 16 (44.4) | 6 (33.3) | NS |

| Respiratory complications | 14 (38.9) | 3 (16.7) | NS |

| Vascular complications | 3 (8.3) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Biliary complications | 9 (25) | 6 (33.3) | NS |

| Rejection | 6 (17.1) | 2 (11.1) | NS |

| Post-lt metabolic and cardio-vascular disease (5-years follow-up postlt) | |||

| AHT postLT | 19 (63.3) | 13 (72.2) | NS |

| Dyslipidemia postLT | 22 (73.3) | 14 (77.8) | NS |

| DM postLT | 19 (63.3) | 10 (55.6) | NS |

| BMI postLT≥25 | 26 (89.7) | 14 (82.4) | NS |

| Obesity postLT (BMI≥30) | 14 (48.3) | 8 (47.1) | NS |

| Hyperuricemia postLT | 7 (23.3) | 4 (22.2) | NS |

| Renal insufficiency post LT | 10 (33.3) | 8 (44.4) | NS |

| OH postLT | 1 (3.3) | 1 (5.6) | NS |

| Smoking postLT | 5 (18.5) | 0 (0) | 0.019 |

| CV disease postLT | 6 (20) | 4 (22.2) | NS |

| Other post-lt complications | |||

| Dysfunction in liver tests | 18 (62.1) | 6 (35.3) | 0.079 |

| De novo tumors | 3 (10.3) | 0 (0) | NS |

| HCC recurrence | 1 (3.3) | 2 (11.1) | NS |

| Retransplantation | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Causes of mortality post-liver transplantation | |||

| Tumors | 1 (10) | 2 (66.7) | NS |

| Immunosupression | 5 (50) | 1 (33.3) | NS |

| CV events | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Graft dysfunction | 2 (20) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Graft cirrhosis | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | NS |

Results: n (%); mean (standard deviation).

NS: not significant.

AHT: arterial hypertension; BMI: body mass index; CV disease: cardiovascular disease; CV events: cardiovascular events; DM: diabetes mellitus; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; NASH: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; OH: alcohol; post-LT: post liver transplantation.

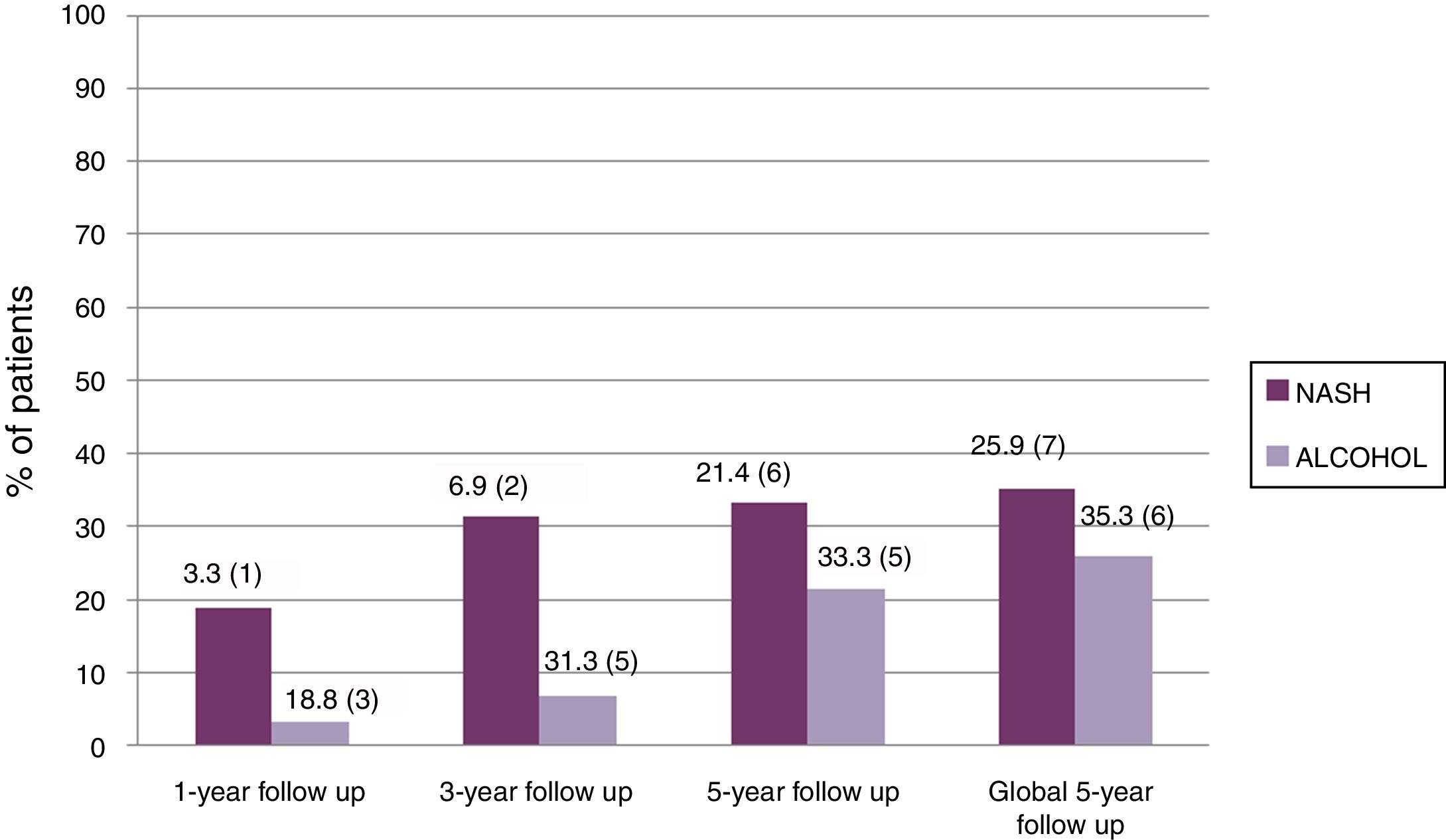

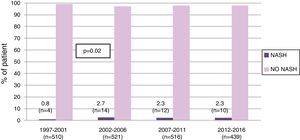

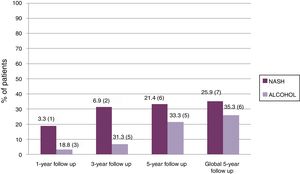

Table 2 summarizes the 5-year complications including metabolic risk factors and CV events. No differences were observed between groups except for tobacco use, which was more common in the alcoholic than in the NASH group without reaching statistical significance. Significant differences were observed regarding other post-LT complications, including de novo tumors and HCC recurrence (Table 2). More specifically, de novo tumors occurred more frequently in the alcohol group than in NASH (10.3% vs 0%; one case of lung carcinoma, one lymphoma and one basocellular skin carcinoma) but without reaching statistical differences. In terms of HCC recurrence, there were two cases in the NASH group, one of which corresponded to an outside-Milan tumor. In addition, abnormalities in liver tests more than 6 months post-LT were more commonly observed in the alcoholic group than in NASH patients (62% vs 35%; p=0.079). Interestingly, no significant differences were obtained comparing the NAFLD score at 1, 3 and 5 years post-LT in NASH (−0.546, −0.287 and −0.677, respectively) and alcohol (−0.292, 0.055, 0.197, respectively) groups (p: ns) (Table 3). Ultrasonographic steatosis was more frequent in the NASH group, particularly at 3 years post-LT, but without reaching statistical significance (Fig. 2).

NAFLD score in patients with NASH vs Alcoholic cirrhosis:.

| ALCOHOL (n=36) | NASH (n=18) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIRST YEAR after LT | −0.292 | −0.546 | NS |

| THIRD YEAR after LT | 0.055 | −0.287 | NS |

| FIFTH YEAR after LT | 0.197 | −0.677 | NS |

Results: NAFLD score.

NS: not significant.

LT: liver transplant; NASH: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

Two patients were retransplanted, both in the alcohol group due to artery thrombosis. The number of deaths during the follow-up was similar in both groups (n=10–26.3% – in the alcohol vs n=3–16.7% – in NASH; p=ns). Post-LT survival in both groups is shown in Fig. 3. One, 3 and 5 yrs survival was 83%, 78% and 72% in the alcohol group compared to 89%, 89% and 83% in the NASH group (p=0.21).

Major causes of mortality in the alcohol group were those related to immunosuppression (41%), mostly infections followed by tumor-related (23.5%), mostly de novo tumors. In turn, in those transplanted for NASH-related cirrhosis, two patients died due to HCC recurrence (67%) followed by immunosuppression-related causes, mostly infections (33%) (Table 2).

4DiscussionThe outcome of patients undergoing LT for CC/NASH related cirrhosis is still unclear. The frequent coexistence of risk factors associated with CV disease may result in impaired post-transplantation survival. However, these same factors are also frequent in other LT indications such as those with alcoholic cirrhosis. We hence analyzed our results in a group of patients referred for LT with the diagnosis of CC and compared the outcome of those who fulfilled the criteria of NASH-related cirrhosis to a matched group of patients transplanted for alcoholic cirrhosis.

We chose the alcohol group as comparator because of the similar clinical profile between these two groups in terms of CV risk and histologic similarities (steatosis combined with necroinflammation). Although the HCV group is also known to be at risk for CV disease, we did not include it as a comparator since the outcome has been mostly linked to recurrent disease in the past.

The main conclusions of our study can be summarized as follows: (i) the majority of patients referred to LT with the diagnosis of CC were, in fact, patients with fatty liver disease, data concordant with that of prior studies [10,21–23]; (ii) although the proportion of patients with diagnosis of NASH-related cirrhosis undergoing LT has increased overtime in our center, the numbers have remained fairly stable in the last 10 yrs and are clearly inferior to those reported by US centers [10,15,21,30]; (iii) pre-transplantation CV risk factors tended to be higher in the NASH group compared to the alcohol group, but the only difference that reached statistical significant was obesity; (iv) HCC was more common in the NASH group with a percentage slightly higher than that reported in other series [31–33]. This higher prevalence of HCC in patients with NASH-cirrhosis may be related to the high percentage of obesity and diabetes in these patients [33,34]. The metabolic syndrome includes a group of interrelated metabolic risk factors such as diabetes, AHT, dyslipidemia and central obesity. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia play a central role. Hyperinsulinemia causes cellular oxidative stress and increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Chronic inflammation may promote cellular mutations that could potentially lead to HCC development [35]. The overall evidence is suggestive of an increased HCC risk in obese and overweight individuals [34–40]. All these findings highlight the need for adequate screening in this population [33–35]; (v) post-transplantation outcome was similar in both groups, both in terms of 5-year survival as well as regarding the development of metabolic complications and CV disease. The main fear when transplanting patients with NASH-related cirrhosis is the potential for recurrence of the primary disease as well as increased mortality due to CV events [41,42]. In some published studies, short and medium-term survival appears to be similar to other indications [15,21,30]. The lack of differences in post-transplant CV events between the NASH and alcohol population may be due to the similar high prevalence of CV risk factors found in these patients, but also potentially, a worse post-LT control of these complications in the alcoholic group. It is not unreasonable to think that while the main concern post-LT in the alcoholic group is to avoid alcohol recidivism, physicians and also NASH-patients may be more prone to fulfill the recommendations regarding the control of risk factors of CV disease.

We calculated the NALFD score as an indirect measure of injury related to steatohepatitis but did not observe a significant increase over time nor differences between the two groups. Regarding the relatively low progression of NASH (based on NAFLD score) despite the significant increase in risk factors such as obesity, dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension and diabetes, we cannot guarantee the validity of our findings given the lack of protocol serial liver biopsies. Future studies based on these biopsies are required to better estimate disease progression. These studies will ultimately determine the degree of concordance between histological findings and NAFLD score in the liver transplant setting.

There are some limitations of this study, particularly the small sample size. In addition, protocol liver biopsies were not consistently available to better assess the recurrence of primary disease. Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that some patients from the alcohol group were in fact individuals with the so-called “alcoholic steatohepatitis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH-NASH)” diagnosis.

In summary, most CC in our center were due to fatty liver disease. Although the number of patients undergoing LT for NASH-related cirrhosis is greater today than 15 yrs ago, we have not observed a progressive increase in this indication in our center, the largest in Spain, and NASH alone continues to be a rare indication. HCC is more frequent in NASH related cirrhosis than in alcoholic patients, with recurrence of HCC being the first cause of death in the former group. Post-LT survival is similar to that achieved by those undergoing LT for alcoholic cirrhosis. CV events also occur with a similar incidence so that measures to control CV risk factors should target both NASH and alcohol-related LT recipients.

The main practical conclusions from this study are two-fold. First, the increase in NASH as an indication for LT is also a reality in our center, but with numbers still far from those reported in United States centers, a circumstance that needs to be taken into account when modeling future needs in the LT setting; Second, given the same outcome post-liver transplantation for alcohol and NASH related indications, there is a need to strictly monitor and adequately manage CV risk factors in both conditions, not only in those transplanted for NASH related liver disease.

In conclusion, NASH-cirrhosis is an acceptable indication for LT with good midterm results. Control of metabolic risk factors is essential for maintaining the good outcome in the long term, not only in NASH cases but also in other at-high-risk indications of LT, particularly in those undergoing LT for alcoholic cirrhosis.AbbreviationsAHT arterial hypertension alanine aminotransferase alcoholic steatohepatitis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis aspartate aminotransferase body mass index cryptogenic cirrhosis cardiovascular diabetes mellitus gammaglutamyl-transpeptidase gastrointestinal bleeding hepatocellular carcinoma hepatitis C virus liver transplant/liver transplantation model for end-stage liver disease non alcoholic fatty liver disease non alcoholic steatohepatitis not significant alcohol pathology spontaneous bacterial peritonitis standard deviation World Health Organization

Beatriz Castelló, Victoria Aguilera, Marina Berenguer – study concept and design; Beatriz Castelló, M. Teresa Blázquez – acquisition of data; Beatriz Castelló, Victoria Aguilera, M. Teresa Blázquez, Marina Berenguer – analysis and interpretation of data; statistical analysis; Beatriz Castelló, Victoria Aguilera, Marina Berenguer – drafting of the manuscript; Victoria Aguilera, Ángel Rubín, María García, Carmen Vinaixa, Salvador Benlloch, Fernando SanJuan, Eva Montalva, Rafael López, Marina Berenguer – critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; Marina Berenguer – study supervision.

Personal data protectionEvery patient included in the research signed an explicit informed consent form at the moment of the transplantation which clearly explained that your data could be used and published (anonymously and according to the Spanish Personal Data Protection Law) for the research of complications and specific aspects on the hepatic transplantation.

Funding sourcesVictoria Aguilera received a grant by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Research Center Carlos III (Instituto de investigación Carlos III) (grant number PI13/01770).

Marina Berenguer received a grant by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Research Center Carlos III (Instituto de investigación Carlos III) (grant number PI19/01360). This study is also supported by Networked Biomedical Research Center of Hepatic and Digestive Diseases, “Ciberehd” funded by the Research Center Carlos III (Instituto de investigación Carlos III).

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.