Chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) affects 170 million people worldwide1,2 and 1.8% of the population of the USA. The principal route of transmission before the 1990s was transfusion of blood and blood derivatives. At present, the prevalence of chronic infection is greater than 60% in patients with hematological dysfunctions (hemophilia, thalassemia), renal diseases requiring hemodialysis or transplantation, and indinavir-associated renal complications.1,2 However, transmission by transfusion has been substantially reduced by the implementation of laws that require all blood donors to be tested for the presence of anti-HCV antibodies. The incidence of chronic HCV infection is greater than 80% among people addicted to intravenous drugs and among people with human immunodeficiency syndrome.1,2

HCV and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection is common in patients who acquire HIV by parenteral routes. Increased survival rates in patients with HIV resulting from the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and faster development of liver cirrhosis in patients with HIV have made treatment of chronic hepatitis C a priority in patients with HIV coinfection.52,55,56,65

Treatment of HIV-HCV coinfectionThe primary objectives of treatment of patients with HCV-HIV coinfection are:

- 1.

to eliminate the HCV,

- 2.

to normalize levels of aminotransferases,

- 3.

to reduce the risk of transmission,

- 4.

to reduce necroinflammatory activity in liver tissue and stop or reduce the progression of fibrosis, which is normally fast in this group of patients,

- 5.

to reduce the probability of hepatotoxicity in patients requiring treatment with a combination of several antiretrovirals, and

- 6.

to achieve fast immune recovery in patients receiving HAART.91

Patients considered prospects for treatment should be those in whom:

- 7.

the presence of chronic HCV or decompensated liver cirrhosis (Child score = A) has been confirmed,

- 8.

viral loads of HCV are detectable,

- 9.

viral loads of HIV are undetectable or less than 10,000 IU with the proviso that those with HIV viral loads up to 50,000 IU may be considered under special circumstances,

- 10.

alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels are persistently elevated,

- 11.

fibrosis is evident from liver biopsies,

- 12.

levels of CD4+ are greater than 350 cells/mL (ideally, > 500 cells/mL),

- 13.

levels of pretreatment lactic acid are within normal levels,

- 14.

HAART-induced hepatotoxicity is absent,

- 15.

abstinence from alcohol consumption or intravenous drug use has been documented, or

- 16.

a history of adherence to HAART (if applicable) has been documented.

Although the appropriate time to initiate treatment with interferon and ribavirin is when the patient meets the foregoing criteria, the outcome of treatment is affected by whether it occurs before or after initiation of HAART. If the patient is treated for HCV before HAART, the risk of hepatotoxicity to antiretrovirals is less, immune recovery is faster, the risk of morbidity and mortality is reduced, and adherence to treatment is better.91 However, in the majority of cases, HAART will already have been initiated when they are considered for HCV treatment.65,73

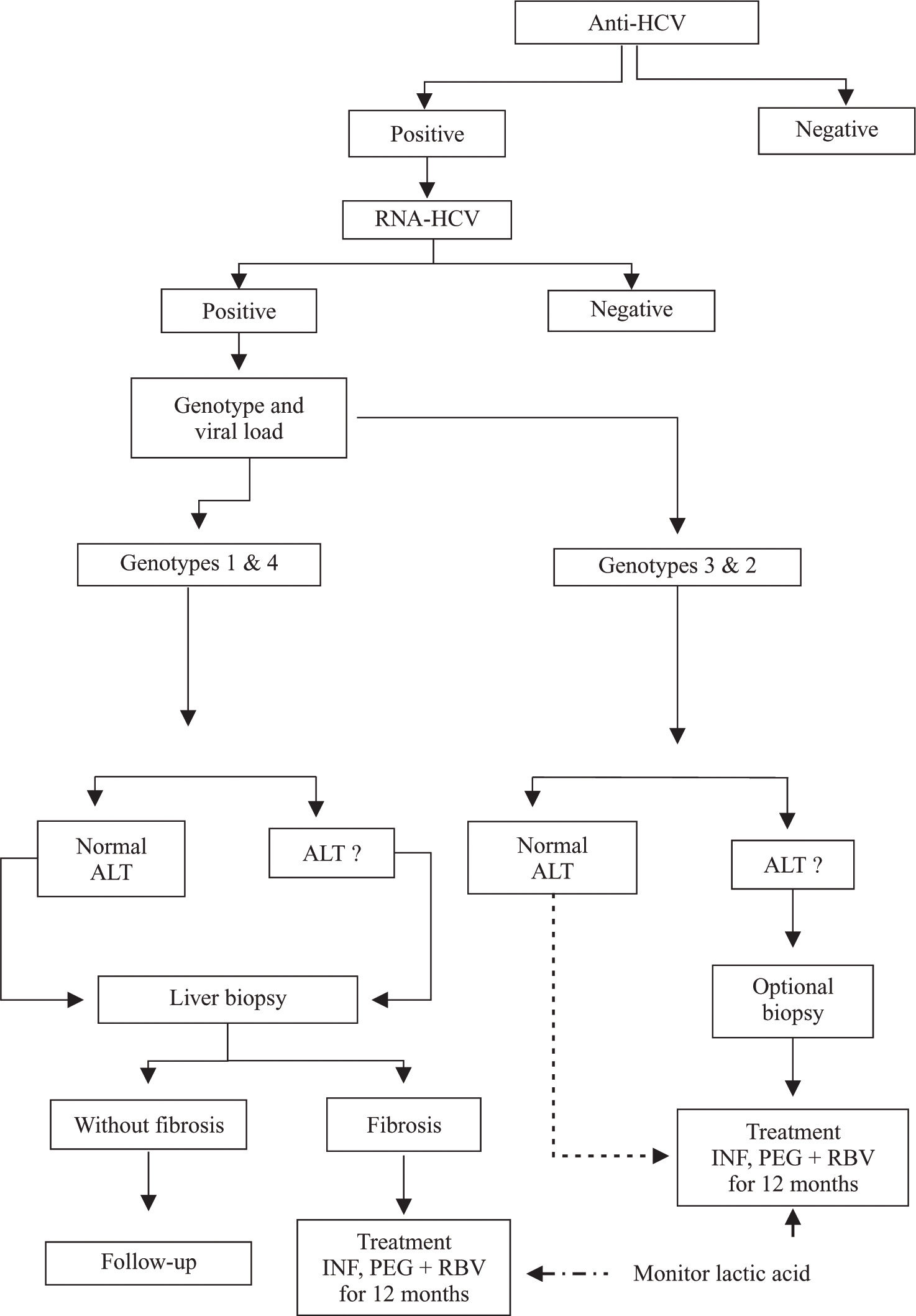

The algorithm for treatment of patients with HCV-HIV coinfection proposed by a panel of international experts differs slightly from that for patients who only have HCV infection, because patients with coinfection have faster progression to liver cirrhosis than patients with HCV alone. For patients with HCV-HIV coinfection, it is recommended that viral load and genotype should be established after serological diagnosis of infection by HCV. Patients with elevated aminotransferase levels and HCV genotypes 1 and 4 should be treated for 12 months, and patients with elevated aminotransferase levels and HCV genotypes 2 and 3 should be treated for 6 months. Both groups should be treated with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin. However, in patients with persistently normal levels of aminotransferases, it is necessary to take a liver biopsy, because those with fibrosis (F1 to F4) are prospects for treatment (Figure 1). In patients in whom fibrosis is absent, liver biopsies should be repeated after 2 to 3 years.74,76,77,91 Recently, it was recommended that treatment similar to that given to patients with HCV genotypes 2 or 3 who are HIV-negative should be given to HIV-positive patients with HCV genotypes 2 or 3 who have persistently normal aminotransferase levels and viral loads regardless of whether hepatic lesions are present. This recommendation was made because of the high levels of response in these genotypes.

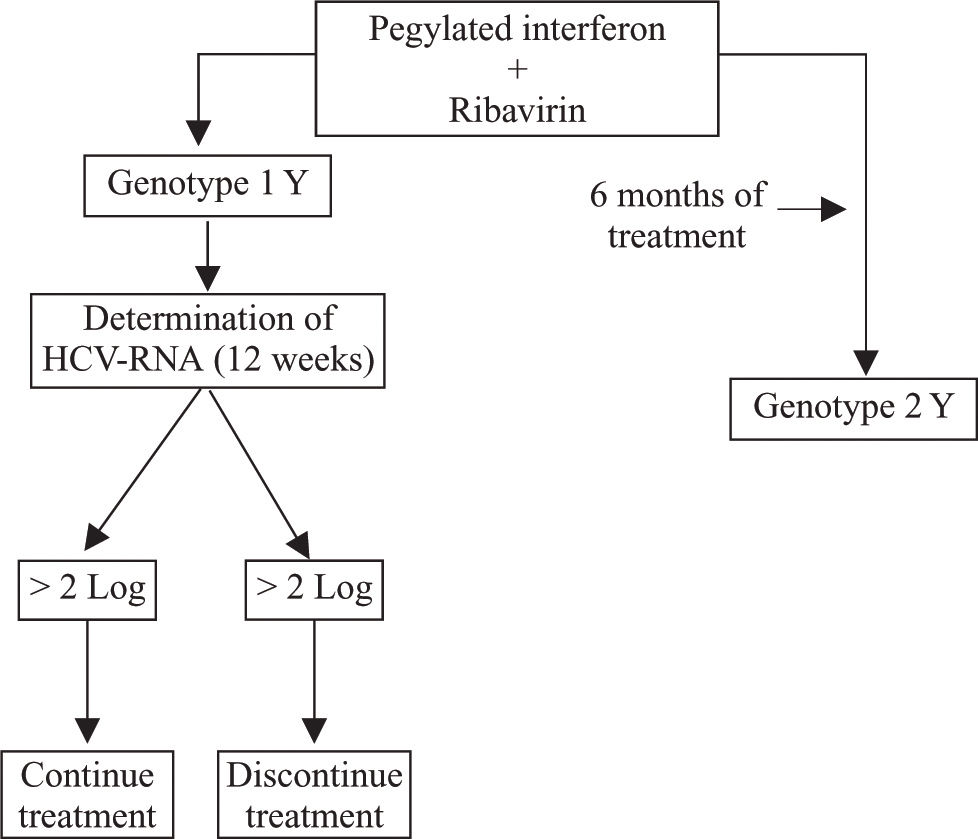

Kinetic studies of early and sustained virological responses proved that criteria for the duration of treatment of patients infected with HCV alone are applicable to those with HCV-HIV coinfection.92-96 Therefore, if a reduction of viral load greater than 2 log10 is not attained at week 12 of treatment, it is advisable to discontinue treatment in view of the low probability of success (Figure 2).

The sustained viral response to interferon monotherapy in patients with HCV-HIV coinfection is low. Therefore, the standard treatment at present is interferon alfa plus ribavirin, which results in a sustained viral response rate of 35%-40% or greater, depending on the genotype. Ribavirin is an analog of guanosine and has a broad antiviral spectrum.58 However, it does not inhibit the replication of HCV when administered alone. It reduces ALT levels and improves certain forms of liver histology. The results of five pilot studies on responses to combined therapy (standard interferon + ribavirin) in HIV-negative patients were similar (Table I). These studies included hemophiliacs and intravenous drug addicts coinfected with HIV and HCV and receiving HAART. All patients had sustained viral responses of about 40%. In the study of Zylberberg et al., 14% of nonresponders to interferon monotherapy had sustained responses to combined therapy.48 Side effects reported by coinfected patients are similar to those reported by immunocompetent patients, but the incidence of anemia was higher in patients receiving zidovudine or stavudine.47,60,64 However, in most cases, the anemia can be successfully managed by administration of erythropoietin. Plasma levels of HIV RNA did not change during treatment, but in 50% of cases, the absolute count of CD4+ cells decreased. The CD4+ cell count and CD4/CD8 cell count remained unchanged.48,64

Results of pilot studies of interferon plus ribavirin treatment of HIV–HCV coinfected patients receiving HAART.

| Author | Landau | Morsica | Dieterich | Zylberberg | Sauleda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 |

| No. patients | 20 | 12 | 20 | 21 | 20 |

| Age | 41 | 38 | 47 | 40-7 | 30-9 |

| % ADVP/TX | 90/10 | NR | NR | 81/15 | 0/100 |

| Analog pirimidin | 11 | 12 | 19 | 20 | 12 |

| CD4+ cells/mm3 % Cirrhosis | 350 ± 153 45 | 421 (314-777) NR | 430 3/20 | 330 (55-600) 57 | 490 ± 176 NR |

| % Genotype 2/3 | 25 | NR | 45 | 43 | 25 |

| Resp. end treatment | 10 (50%) | 8 (73%) | NR | 6 (24%) | 9 (45%) |

| Sustained resp. | NR | NR | 8 (40%) | 3 (14%) | 8 (40%) |

| Changed CD4 | SI | SI | SI | NO | SI |

| Changed HIV replication | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Interferon dose | 3 MU 3v x wewk/6 m 1000-1200 | 6 MU 3v x wewk/6 m 800-1200 | 3 MU 3v x wewk/6-800-1200 | 3 MU 3v x wewk/6-12 m 1000-1200 | 3 MU 3v x wewk/6-12 m 800 |

| RBV (mg) | 1000-1200 | 800-1200 | 800-1200 | 1000-1200 | 800 |

Landau AIDS 2000;14:839-44

Dieterich AASLD 1999;422

Morsica AIDS 2000;14:1656-8

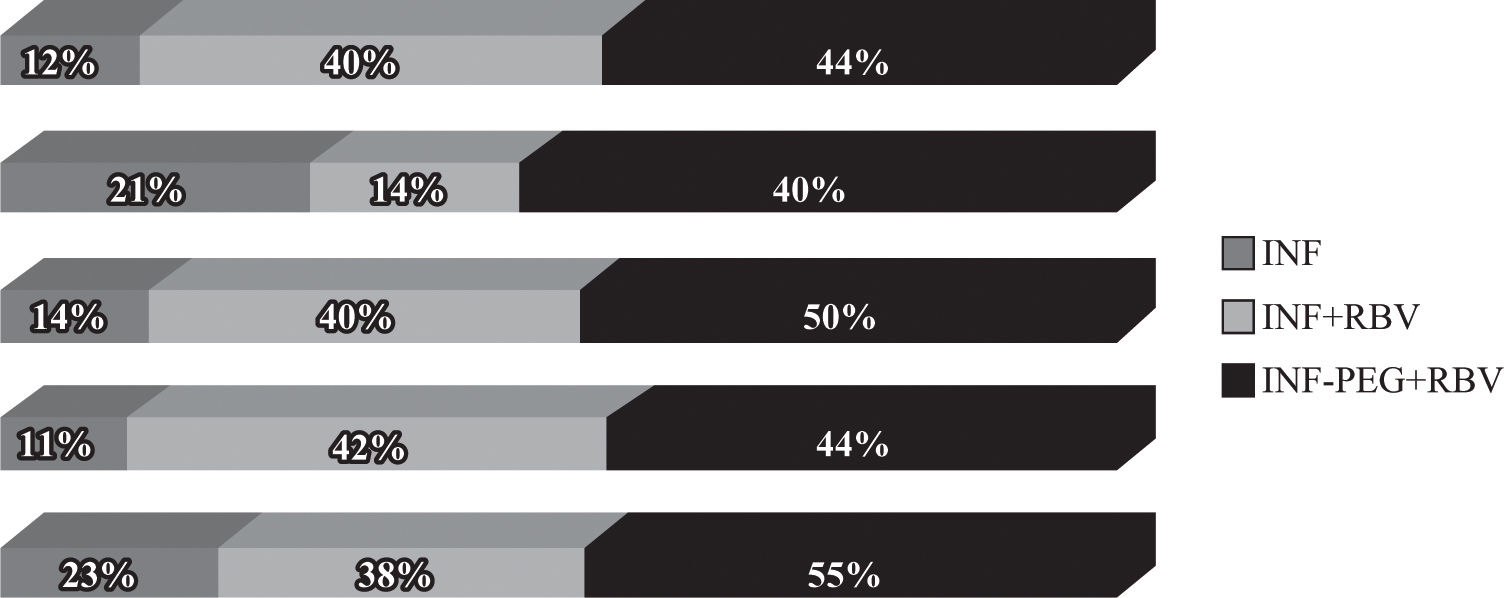

Various studies have been initiated to investigate the effect of pegylated interferon in HIV-HCV coinfected patients. The efficacy and safety for HIV-HCV coinfected patients of a combination of interferon alfa-2b (3 MIU three times per week) and ribavirin (800 mg/24 h) were compared with that of a combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2b (1.5 μg/kg body weight once per week) and ribavirin (800 mg/24 h). A preliminary report64 indicated that the side effects of these combinations are similar (decreased levels of hemoglobin, platelets, and neutrophils; decreased absolute counts of CD4; unchanged CD4 cell count and viral loads of HIV). The early virological response to treatment with pegylated interferon of HIV-HCV-coinfected patients is similar to that of HIV-negative patients.92-96 Several studies have shown that the mean for early virological response to treatment with pegylated interferon in HIV-HCV coinfected patients of all HCV genotypes is greater than 50% and that the difference between responses to treatment with interferon alfa-2b and treatment with pegylated interferon alfa-2b is greatest for carriers of HCV genotype 1 (Table II).

Percentage of HIV–HCV coinfected patients with undetectable HCV RNA at week 24 after initiation of treatment with standard interferon plus ribavirin or pegylated interferon plus ribavirin.

| Genotypes | Interferon α-2b | Pegylated interferon α2a |

|---|---|---|

| All genotypes | 13/27 (48%) | 15/26 (58%) |

| Genotypes 1 & 4 | 5/18 (28%) | 7/15 (47%) |

| Genotypes 2 & 3 | 8/9 (89%) | 8/1 (73%) |

However, the final results of these studies (Figure 3) showed that sustained responses are lower in coinfected patients than in HIV-negative patients and that coinfected patients with HCV genotype 1 have a lower response than coinfected patients with other genotypes (Table III). Sustained response rates in the RIBAVIC95 and APRICOT93 studies, which include large numbers number of patients, were 27% and 40%, respectively, which is lower than that documented for HIV-negative patients (> 50%).

Management of HIV-HCV-coinfected patients with a combination of standard interferon, ribavirin, and mantadite had no greater efficacy than therapy with standard interferon and ribavirin.97

Treatment of 15% of coinfected patients is discontinued because of side effects, which is similar to that of HIV-negative patients. The most frequent side effects are flu-like syndrome, headache, myalgias, arthralgias, hyporexia, anemia, depression, irritability, insomnia, and gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Various studies reported the occurrence of lactic acidosis, pancreatitis, myopathy, and neuropathy. These are serious side effects, especially in patients who receive didadosine, because its phosphorilation is increased by ribavirin, causing mitochondrial DNA depletion.98,99 Patients receiving HAART with nucloside reverse transcriptase inhibitors develop lactic acidosis because of mitochondrial DNA depletion, which is potentiated by ribavirin.60-64 Therefore, it is necessary to monitor levels of lactic acid before and during pegylated interferon plus ribavirin treatment of patients who receive HAART with nucleoside analogs. The great diversity of antiretroviral drugs existing allows us to change the anti-retroviral rules in these situations and to avoid as long as possible the risk of the appearance of this complication.61,64 Premedication with paracetamol increases tolerance of the side effects of treatment. It is advisable to initiate anti-depressive management promptly if patients show signs of developing depressive syndrome. In conclusion, the best treatment is a combination of pegylated interferon and ribavirin.

Recommendations of the consensus panelWhat is the ideal time to treat this group of patients?

Before they require management with antiretrovirals to stabilize HIV infection because the tolerance of and adherence to treatment is high, levels of CD4+ are high, and the hepatotoxic effect of antiretrovirals is absent.

Evidence quality: 2

What is the minimum concentration of CD4+ cells for initiating treatment against HCV?

The minimum CD4+ level for commencement of treatment against HCV is 200 cells/mL, because there is evidence that most patients with values lower than this do not have sustained virological responses. However, the ideal CD4+ level is 500 cells/mL.

Evidence quality: 2Is it advisable to conduct biopsies in this group of patients?

Liver biopsies are recommended for HCV-HIV-coinfected patients. There is sufficient evidence of accelerated progression of fibrosis in this group of patients, and therefore the development of cirrhosis is faster than that of patients without HIV infection.

Evidence quality: 2Who are the best prospects for treatment among patients using antiretrovirals?

Patients with:

- •

CD4+ levels greater than 350 cells/mL

- •

undetectable viral loads of HIV

What is the ideal treatment for these patients?

The panel of consensus recommended combined therapy with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin for 48 weeks regardless of the genotype and in addition to antiretroviral therapy if indicated. The criteria of early viral responses at the end of treatment and sustained responses should be applied as for patients without HIV.

Evidence quality: 2