The aim of this study is to analyze how certain voice features of radio spokespersons and background music influence the advertising effectiveness of a radio spot from the cognitive, affective and conative perspectives. We used a 2×2×2×2 experimental design in 16 different radio programs in which an ad hoc radio spot was inserted during advertising block. This ad changed according to combinations of spokesperson's gender (male–female), vocal pitch (low–high) and accent (local–standard). In addition to these independent factors, the effect of background music in advertisements was also tested and compared with those that only had words. 987 regular radio listeners comprised the sample that was exposed to the radio program we created. Based on the differences in the levels of effectiveness in the tested voice features, our results suggest that the choice of the voice in radio advertising is one of the most important decisions an advertiser faces. Furthermore, the findings show that the inclusion of music does not always imply greater effectiveness.

The importance of radio as a means of communication is reflected in the upward trend in audience and the increasing number of radio listeners registered in 2012 by AIMC-EGM (Spanish Association of Communication Media Research-Study on Media Audiences). The number of listeners of bigger stations increased in over a million compared to the previous year (AIMC-EGM, 2012), reaching a historical maximum in Spain. However, this fact is not reflected in advertiser's media planning. In Spain, despite the radio being the second media with higher penetration, it still ranks number four in terms of advertising investment with 453.5 million Euros and 9.8% of investment earmarked for conventional media in 2012 (Infoadex, 2013). Its qualities as an advertising mean are well documented (Arens, 2008; Kelley and Jugenheimer, 2004; Belch and Belch, 2001), and the following are worth highlighting: (1) its high penetration (61.9%) (AIMC-EGM, 2012), which despite being a highly fragmented media allows high levels of coverage for different target audiences and has a great capability to segment audiences through several radio station convergence; (2) its ability to generate mental images in the audience (Soto Sanfiel, 2008; Bolls and Muehling, 2007) and to personalize the message, which in turn leads to greater effectiveness in terms of persuasion and action (Ingram and Barber, 2005); and (3) its high credibility as a means of information, which according to Metroscopia's latest study (Toharia, 2011) situates it among the top 10 institutions trusted by Spaniards, and this trust is transferred to its advertising messages (Muela Molina, 2010). However, this great communicative potential is underused by the agents involved in advertising communication and its high levels of audience and credibility are not reflected in advertising investment, particularly when everything seems to be limited to the online world. This situation requires studies that provide advertisers with the key to guarantee effectiveness in a media whose inherent qualities seem stable, unlike other means like television, or even the Internet, where changes in the environment affect the process of advertising planning making it more and more difficult to achieve the communication's targets.

Radio advertising effectiveness depends on several factors related to its macro and micro-structure (Rodero, 2011). On a micro-structural level, “phonoaesthetic function” has aroused great interest in the literature, as the effect of a message depends not only on the strict meaning of its words, but also on the way it is transmitted. Therefore, some studies focus on the role of phonoaesthetic function in the effectiveness of messages and analyze the oral expression transmitted through acoustic features, which can reveal information such as the shape, size, texture, movement of what is described as the spokespersons’ physical appearance, mood and personality. Thus, by manipulating the features of phonoaesthetic function (vocal pitch, timbre, intensity, etc.) one can complete, alter or change the meaning of the same semantic content.

Apart from music, sound effect and silence, the spokesperson's voice is one of the main elements of advertising language used to transmit the sense and affective dimension of messages (Rodero, 2007). In advertising, where there is no visual component, the voice becomes crucial, as it is the only tool to evoke additional information (Krauss et al., 2002). Therefore, the voice's nonverbal features have to be taken into account when the communication is persuasive, as established in a report from the Radio Advertising Bureau (RAB) (2013) that considers that the briefing should include the type of voice intended to use. In this line, Whipple and McManamon (2002) highlight that choosing a spokesperson is one of the most important decisions faced by an advertiser, where it is of utmost interest to identify the voice characteristics that can enhance advertising effectiveness.

The literature on advertising has dealt with both the importance of the voice and its characteristics through content analysis (Rodero, 2011; Muela Molina, 2010; Perona Páez, 2007), but the same has not been done with the analysis of its advertising effectiveness. That is why the aim of this paper is to identify and analyze the factors regarding the vocal element in radio spots that have an influence on their effectiveness in the cognitive, affective and conative levels.

More specifically, we intend to (1) evaluate how certain voice features affect the evaluation of a spokespersons and their voice, and (2) analyze how these features affect radio advertising effectiveness using cognitive (unaided recall, aided recall and recognition), affective (liking, attitude toward the ad and attitude toward the brand) and conative measures (intention to act). Via an experimental design, we analyzed the micro-structural qualities of the voice regarding the phonoaesthetic function, namely vocal pitch, gender and accent of the spokesperson. In addition, given the importance of music in the advertising industry as a generator of emotions and thus as a factor which can positively influence effectiveness, this paper also deals with the influence of music on effectiveness.

Background and hypothesesThere are two closely linked lines of investigation in the literature aimed at identifying the qualities of the radio as a means of advertising. The line which has drawn more attention analyzes the ability of a sound message to stimulate the creation of mental images in the listener, as opposed to audiovisual media, where the inclusion of an image limits the possibility of activating the receiver's imagination (Bolls and Lang, 2003; Bolls and Muehling, 2007; Potter and Callison, 2009; Potter and Choi, 2006). The second line focuses on the factors affecting their effectiveness, not only on a macro-level, mainly through the study of serial position (the position of the spot within the advertising block) analyzed by Rodero (2011), advertising density and the effects of primacy and recency contrasted by Riebe and Dawes (2006) and then analyzed by Potter et al. (2008) but also on a micro-structural level, where this paper is framed and further developed. Generally, when dealing with advertising effectiveness people refer to the ability of the advert to achieve its advertising goals and it is measured within the framework of a model on response to advertising. There is no single universally accepted model of advertising effectiveness, but rather a number of different models which deal with the same process from different perspectives and which take into account the influence of a great number of variables in the process (Beerli and Martín, 1999). These models contemplate a multi-stage advertising response process with an underlying sequence of cognitive, affective and conative stages. These stages are directly related to the three functions of advertising: inform, create attitudes or feelings toward the advertised object, and trigger a behavior or action in individuals. Following Martín-Santana and Beerli-Palacio (2013) there are multiple techniques for measuring advertising effectiveness and they are closely linked to the sequence of effects of advertising response models. According to these authors, the measures can be classified according to the three levels of individual response to advertising:

- –

Cognitive techniques. These evaluate the ability of the advert to attract the individual's attention and the individual's knowledge and understanding of the advert. They also assess the advertisement's ability to be memorized and transmit the message. Among these techniques are measures of notoriety and measures based on memory.

- –

Affective techniques. These measure the type of attitude that an advert generates in individuals. The most relevant are liking, attitude toward the advert and attitude toward the brand.

- –

Conative techniques. These techniques determine if the response behavior of individuals is in the desired direction. The most widely used is intention to act.

On a micro-structural level, the main elements of radio advertising language deal on the one hand with factors related to the characteristics of advertising formats such as information density and narrative structure, and on the other with the resources used in the components of the message, restricted mainly to word and music. Regarding the word, the voice as a phonoaesthetic resource and its pragmalinguistic strategies have been the aim of multiple content analyses in radio messages, whilst less studies focus on their advertising effectiveness. In terms of prosodic features of the voice, the main acoustic qualities that differentiate them in radio advertising are mainly the timbre, vocal pitch, intensity (volume), accent and duration. Spokespersons can use these qualities for instance by varying their pitch, increasing the intensity or lengthening the syllables to achieve different communicative aims on their target audience.

In order to further develop the theory on micro-structural resources and its use, the hypotheses of this study revolve around two basic components of radio advertising messages, namely the use of the voice through vocal pitch, accent and gender, and the use of music.

Vocal pitchVocal pitch is produced by a series of openings and closings of the vocal chords in a unit of time, emitting a continuous sound also known as fundamental frequency. Depending on the characteristics of the vocal muscles, their tension and the flow of air among other factors, the vocal pitch will be higher or lower. The greater the tension in the vocal chords, less thickness and higher the opening and closing of them, the higher the vocal pitch will be.

On the contrary, the thicker the vocal chords, less tension, and lower frequency of opening and closing, thus the lower the vocal pitch (Ashby and Maidment, 2005; Rodero, 2001). Vocal pitch is measured in Hertz (Hz), this being the equivalent to a complete opening and closing cycle in one second. According to some authors, the male fundamental frequency ranges from 80 to 200Hz and the female one from 150 to 300Hz (Soto Sanfiel, 2008; Ashby and Maidment, 2005). More specifically, Soto Sanfiel (2008) defines the range of female voice between 189 and 225Hz for a high-pitched voice and between 115 and 151Hz for a low-pitched one; whereas male high-pitched voices range between 152 and 178Hz and low-pitched one between 98 and 125Hz.

Research on vocal pitch suggests that low-pitched voices are perceived as more pleasant, as they are associated with credibility, truthfulness, safety, tranquility, naturalness, persuasion, power, closeness, attractiveness and trust; on the other hand high-pitched voices tend to be associated with childhood, weakness, coldness, boredom, nervousness, informality, immaturity, and are perceived as less safe, less truthful, less credible and less persuasive (Chattopadhyay et al., 2003; Cohler, 1985). That is why authors recommend low vocal pitch in audiovisual messages, regardless of spokesperson's gender, particularly in informative messages where credibility is one of the most valued qualities (Rodero, 2007). Based on these results, this investigation proposes the following two hypotheses to understand the extent to which vocal pitch is a key element in shaping the listener's attitude toward the spokesperson, as a person and professional, and toward the voice of the spokesperson as a communicative resource. In other words, we will analyze the extent to which the use of low pitch versus high vocal pitch generates a more favorable attitude in the listener toward the spokesperson in terms of credibility, trust, safety, friendliness and honesty, among other aspects, as well as a more favorable attitude toward the spokesperson in terms of liking, persuasion and credibility.H1 The use of low-pitched voices in radio spots generates a more favorable attitude toward the spokesperson than high-pitched voices. The use of low-pitched voices in radio spots generates a more favorable attitude toward the voice of the spokesperson than high-pitched voices.

On the other hand, some studies have shown that the listener's evaluation of a low-pitched voice versus a high-pitched one depends on the gender of the spokesperson because, as Rodero (2001) shows, a low vocal pitch is a determining factor in male voices for it to be rated as more pleasant, whereas it is only a considerable factor in female spokespersons.

Research in psychology and linguistics has already suggested that for male speakers, low-pitched voices were perceived as more pleasant, attractive and persuasive (Collins, 2000; Zuckerman and Miyake, 1993). In this line Knapp (1980) concludes that a low-pitched voice, mostly male, gives a radio message more authority, as it is more persuasive and convincing because it is associated with physical and emotional power; female voices on the other hand are linked to social abilities. Based on the above we propose the following hypotheses:H3 The effect of low-pitched voices on the attitude toward the spokesperson changes depending on the gender of the spokesperson. The effect of low-pitched voices on the attitude toward the voice of the spokesperson changes depending on the gender of the spokesperson.

According to Chattopadhyay et al. (2003) the voice plays a decisive role in the recipient's response to advertising messages, as it can attract the listeners’ attention and facilitate the generation of favorable attitudes toward the messages. In fact, their study reveals that low-pitched voices exhibited more favorable cognitive responses and more positive ad and brand attitudes. Similarly, Rodero et al. (2010) show that low-pitched voices are seen as more attractive and generate more credibility on their audience, influencing advertising effectiveness. Based on these studies we formulate the following hypotheses:H5a The use of low-pitched voices in radio spots has a greater advertising effectiveness on a cognitive level than high-pitched ones. The use of low-pitched voices in radio spots has a greater advertising effectiveness on an affective level than high-pitched ones. The use of low-pitched voices in radio spots has a greater advertising effectiveness on a conative level than high-pitched ones.

The study of spokesperson's accent – in this context accent being the phonetic characteristics of a speaker – is framed within the analysis of one of the five roles of the voice: idiographic, affective, symptomatic, framing, and emphatic (Rodríguez Bravo, 2002). Our study is included in the framing role, when the sound shape of the voice transmits information about the different social, cultural and geographic groups in which the spokesperson can be framed. This role is linked to the combination of different phonetic traits in a speaker that allow identifying them with a specific social group or locating the geographic origin of the speaker. The latter is what this study understands by local accent.

Research on the influence of accent on advertising effectiveness is scarce, despite several studies having shown that a spokesperson's voice characteristics are determining (Lalwani et al., 2005). Previous studies (Lwin and Wee, 1999; Bradac and Wisegarver, 1984) had shown that accent affects source credibility. Based on these studies, Lalwani et al. (2005) compared the influence of two types of English accents, Standard English accent and local Singaporean accent, Singlish, in different measures of effectiveness. Their results show that Standard English accent scored higher over Singlish in spokesperson's credibility, attitude toward the ad and brand, and purchase intention. However, Singlish generated greater attention toward the ad. In this line, Deshields and Ali (2011) have shown that local accent has a greater influence on advertising effectiveness among individuals who are exposed to this accent. Nevertheless, Edwards (1999) and Morales et al. (2012) point out that standard accents tend to be perceived as more correct and prestigious than local accents. Based on the above we establish the following hypotheses in order to show how the use of accent influences effectiveness:H6a The use of standard accent in radio spots has a greater advertising effectiveness on a cognitive level than local accent. The use of standard accent in radio spots has a greater advertising effectiveness on an affective level than local accent. The use of standard accent in radio spots has a greater advertising effectiveness on a conative level than local accent.

The importance of spokesperson's gender as a variable in studies on radio advertising is mentioned in Chattopadhyay et al. (2003) and Wolin (2003). They state the need to explore the existence of different results in consumer response toward the ad due to spokesperson's gender. This is because although most studies reveal that low-pitched male voices generate higher advertising effectiveness, this is not so evident in the case of female voices. This need is also highlighted in Piñeiro's work (2010), which stated that positive connotations linked to low-pitched voices have been exclusively transferred to male voices. In addition, Rodero et al. (2010) highlight that few studies prove or reject the hypothesis of greater effectiveness of male voices over female ones, despite the prevalence of male over female voices in radio communication. Most of these studies analyze the effectiveness of a voice based on their acoustic qualities, regardless of their gender.

Taking the above into account, a further aim of this study is to contribute by determining whether the prevalence of male features in radio spots observed by Perona and Barbeito (2008) and Rodero et al. (2010) is justified or not, which could open a necessary debate. However, this predominance could be due to the influence of product category and targeted market segment (Perona and Barbeito, 2008) or to the existence of gender stereotypes in terms of voice characteristics that limit the presence of female voices (Rodero et al., 2010). Rodero et al. (2010) shows there are no significant differences in the way listeners process a message whether the voice is male or female. In fact, a greater effectiveness of male voices has not been confirmed, even when the product is linked to a male field or when the person evaluating is a man or a woman. However, Whipple and McManamon's study (2002) showed that, although spokesperson's gender did not affect neutral products (non-gender imaged) or male spokespersons affected products aimed at men, female spokespersons did have a significant influence on the rating of the ad.

According to Wolin (2003), these discrepancies could be caused by the fact that firstly, many of the empirical studies did not report reliability assessments of the dependent measures, calling the reliabilities into question, and secondly, most empirical studies used students as subjects.

Taking all of the above into consideration as well as the belief in the sector that male voices are more effective than female ones, we propose the following hypotheses in order to determine whether the prevalence of male voices in radio advertising is justified or not:H7a The use of male voices in radio spots has a greater advertising effectiveness on a cognitive level than female ones. The use of male voices in radio spots has a greater advertising effectiveness on an affective level than female ones. The use of male voices in radio spots has a greater advertising effectiveness on a conative level than female ones.

In the Spanish market music is, along with the word, the most used radio language component in advertising. More than 80% of the adverts feature this element, although its function is mainly ornamental (Perona and Barbeito, 2008). The widespread use of music in advertising derives from the belief among advertisers that music confers a significant commercial advantage. So, music has also aroused interest among researchers trying to determine its potential to add value and enhance advertising effectiveness. There are numerous studies in the literature highlighting the advantages of using music in advertising, such as attracting attention and enhancing recall (Kellaris and Cox, 1989; Stewart et al., 1990; Brooker and Wheatley, 1994; Olsen, 1995; Allan, 2006)), improving attitude toward the ad or brand (Brooker and Wheatley, 1994; Morris and Boone, 1998; Zander, 2006; Hung, 2000; Gorn, 1982), as well as changing behavior (Kellaris and Cox, 1989; Brooker and Wheatley, 1994; Morris and Boone, 1998). Similarly, Olsen (1995) proved the effectiveness of music cuts in radio advertising, concluding that compared with the use of background music or background silence throughout, cutting music to silence before presenting the crucial information increased listener attention and retention of ad information. Having said this, Dilman Carpentier (2010), Galan (2009), Oakes (2007), Alpert et al. (2005) state that the effect of music on cognitive, affective and conative terms takes place when there is congruence between the music and the message. However, Lavack et al. (2008) highlight that the effect on attitude toward the ad and the brand only takes place when the message requires a high level of cognitive processing by the listener.

Returning to the investigation on the processing of advertising messages that stimulate the creation of images, Potter and Choi (2006) and Bolls and Lang (2003) reinforce these conclusions when comparing high and low structural complexity in radio messages based on micro-structural resources such as music. So, including sound resources such as music enables an almost automatic processing which requires few resources to codify the message but increases resources for processes such as saving and recovering the information in one's memory.

Despite the positive effect of music in advertising effectiveness, results on its influence on the cognitive, affective and conative levels have been contradictory (Sharma, 2011). As Sharma (2011) points out, this contradiction could be due to the existence of non-controlled variables and the methodology used in the experimentation. Thus, based on most of the papers on the influence of music in radio advertising we propose the following hypotheses:H8a The format which combines the use of word and music has a greater advertising effectiveness on a cognitive level than the one using only words. The format which combines the use of word and music has a greater advertising effectiveness on an affective level than the one using only words. The format which combines the use of word and music has a greater advertising effectiveness on a conative level than the one using only words.

In order to avoid the bias detected by Smith (1994) in the reactions of men and women depending on whether the product was targeted at a sex more than the other, the chosen product for the radio spot was blood donation, as it can be considered a neutral product in terms of gender. This is also justified by the homogenous distribution of male (54%) and female (46%) donors, according to the data provided in a report of the Spanish Federation of Blood Donors (Federación Española de Donantes de Sangre, 2012). Every autonomous community has a regional blood transfusion center with a sphere of activity of at least over a million inhabitants. Given that the aim of this paper requires conducting the experiment at least in two regions and that the spot was not modified according to the region, the brand used for the spot was the National Institute of Blood Donation (Instituto Nacional de Donación de Sangre).

Design of the stimuliThe advertising format used was a 20s radio spot, as it is the most common format and duration in this media, as indicated by the Radio Observer (Asociación Española de Anunciantes, 2012). Similarly, following Perona Páez's classification (2007) the chosen advertising style was informative, avoiding a dramatic tone, whereas the narrative style was argumentative following Calsamiglia and Tusón (1999). Our choice is based on the fact that it is the most used style in radio (Perona Páez, 2007) and reflects the relevance of information and argumentation as guarantees of credibility.

As the spokesperson's diction and correct articulation affect recall (Rodero, 2011), four professional radio announcers from Radio Canarias-Las Palmas participated in the recording of the radio spots. Two were male (low pitch and high pitch) and two were female (low pitch and high pitch). In addition, the radio spots only featured one voice to isolate the effect of the spokesperson's voice on effectiveness.

Taking all of these prior requirements into account, the Canarian Institute of Blood Donation and Blood Products (Instituto Canario de Hemodonación y Hemoterapia, ICHH) provided the following copy of a radio spot broadcast several years ago, aimed at both male and female targets aged 18–55. In addition, given that one of our aims is to analyze the effect of accent on effectiveness, the copy text was slightly altered to include essential phonetic elements that distinguish both accents (standard accent and local accent) according to RAE (Real Academia Española (2011)). These differences are included in Fig. 1 and after the phonetic alterations the resulting copy text of the study was as follows: “Voluntary, responsible and altruistic donation improves the quality and efficiency of our health system. Blood and any of its components have an expiration date, so our aim is constant donations. This is a message from the National Institute of Blood Donation. Donate blood.”

On the other hand, given the current relevance of the analysis of music in advertising effectiveness, we decided to design two types of radio spots in terms of radio language: (1) one version only using words and (2) another version using words accompanied by incidental music, i.e. an original music piece without lyrics. The music was created by Gabriel González Pérez, BA in Music Composition, who collaborated in this project. The aim of the music was to support the brand image, it played a secondary though essential role and it had the same duration as the spot.

MethodTo conduct the study we designed a simulated radio space in which we inserted an advertising block comprised of four radio spots. The first spot was the one we intended to test so that the position of the spot would not affect the levels of recall given the primacy effect shown by Potter et al. (2008) and Riebe and Dawes (2006). At the beginning of the experiment, the respondents were told that they were going to listen to a 5-min recording of a radio station; their task was to evaluate the program afterwards and they were not informed of the existence of an advertising block. The recording comprised three radio blocks broadcasted in 2009 so as to avoid the effect of recall: (1) an extract of an interview broadcast in a magazine program in the fourth commercial radio station with highest audience in the evening. We selected a radio announcer that was not one of the most popular so that the respondents would not identify the voice; (2) in the same radio station we replicated an advertising block broadcasted in prime-time (from 06:00 to 12:00) which included a spot with a social purpose that was replaced by the spot we intended to test; we also strategically selected another three ads of the field of the original ads: the food industry, insurance and tourism; the duration was the same as that of the tested spot, thus maintaining the original conditions in which the spot with a social purpose was broadcasted and (3) the last block was selected from two radio stations with the highest audience; it comprised an extract of the news which did not give away the date of the broadcast, the weather forecast and a timeless music hit from the 1980s presented by a radio disk jockey. We decided to insert the radio spot in a block formed by different radio programs to avoid the influence of program type on advertising effectiveness, as some studies have shown (Sullivan, 1990). The audio was made with Adobe Audition CS6 using a multitrack session and fade in and out so the cuts between the selected programs would not be perceived.

In order to test the hypotheses we used a 2 (low pitch and high pitch)×2 (male and female)×2 (Canarian accent and standard accent)×2 (only words and words-music) experimental factorial design. This implied recording 16 versions of the radio spot we intended to test.

Variables in the studyExperiment variablesSpokesperson's vocal pitch: low vs. highThe four radio announcers in charge of recording the different versions of the radio spot were selected by measuring the fundamental frequency of several announcers of the collaborating radio station using the PRAAT program (Boersma and Weenink, 2013), which allows us to analyze, edit and manipulate audio with phonetic purposes. The spokespersons were asked to speak naturally for about a minute, so that we could then measure all the acoustic data to obtain the fundamental frequency of each one of them and classify their voices as high or low pitched. Following the Soto Sanfiel (2008) criteria, the four selected spokespersons showed contrastive voices (male-low pitch: 107Hz, male-high pitch: 160Hz; female-low pitch: 151Hz, female-high pitch: 206Hz). The difference between high and low pitched spokespersons ranged between 50 and 60Hz, a distance that allows distinguishing tones clearly without confusing high and low vocal pitch. For the recordings of the spot in the two accents we intended to test (Canarian accent and standard accent) we used the same spokesperson so as not to alter the timbre and consequently the results. For the recording of the two varieties of Spanish accent we created a transcription of the text including the sounds represented by graphemes, as well as the necessary pauses so that all spots, regardless of the spokesperson, would have the same rhythm and the same duration.

Spokesperson's accent: local vs. standardThe analyzed accents were LA (Canarian accent) vs. SA (Standard Accent), which is the neutral accent in all regions in Spain. The choice of Canarian accent is due to the fact that in the Canary Islands the use of LA in the media is not frequent, SA being the most widely used, especially in advertising (Hernández, 2009). This was also the result of a previous study in which over a weekly period we analyzed 5h of prime time radio in the two radio stations with highest audience levels.

The use of Canarian accent vs. SA in radio advertising had never been analyzed up to now. This implied ignoring the commercial importance of the local variety. This LA tends not to be used, among other reasons, because Canarian accent is usually considered less correct than SA by its own speakers, as Trujillo (2001) shows.

In order to avoid melodic differences between radio announcers, the transcription of the spot also featured the prosodic notation of the phonemes so as to clearly indicate the melodic inflexions of the text. By doing so, the free interpretation of the different spokespersons is avoided and the melody is controlled. This process was supervised by an expert in Phonetics and Phonology to guarantee the correct pronunciation of the phonetic features of every accent according to RAE (Real Academia Española, (2011)).

Radio Spot style: word vs. word and musicTwo versions of the spot were recorded: (1) one using only words and (2) another one using words and music without sound effects and with a purely ornamental function.

Spokesperson's gender: male vs. femaleTaking all of the previous experimental variables into account, every version of the spot was recorded by a male and a female voice.

Dependent variablesAttitude toward the spokespersonThe radio studies conducted by Soto Sanfiel (2008), Lalwani et al. (2005) and Megehee et al. (2003) served as a basis to evaluate the spokespersons in our experiment. These studies used wide scales to evaluate spokesperson's credibility and attitude toward the spokesperson, two very important characteristics in a good communicator. Hence, we designed a scale that encompasses the different dimensions from these studies to obtain a construct with high nomological or content validity. This 5-point Likert scale was then refined and finally comprised 22 items (see Table 1). Before evaluating the spokesperson, the respondents were exposed to the spot again so they could evaluate it after listening to it.

Definitive items of the scales to evaluate spokesperson and spokesperson's voice.

| Attitude toward the spokesperson | |||

| V47 | It is the appropriate person to transmit the message | V74 | The person is competent |

| V48 | The person transmits credibility | V75 | It is an expert |

| V49 | The person is trustworthy | V76 | The person transmits professionalism |

| V50 | The person transmits safety | V78 | The person is nice |

| V52 | The person is reliable | V79 | The person is sociable |

| V55 | The person is irritating | V80 | It is a good natured person |

| V57 | The person is effective | V81 | The person is honest |

| V61 | The person is slow | V82 | The person is sincere |

| V63 | The person is likeable | V83 | It is a warm person |

| V68 | The person is boring | V85 | The person is responsible |

| V72 | The person is qualified | V89 | The person transmits weakness |

| Attitude toward the spokesperson's voice | |||

| V91 | The voice is nice | ||

| V94 | The voice is persuasive | ||

| V95 | The voice is credible | ||

Based on the studies of Rodero et al. (2010) and Whipple and McManamon (2002) we designed a 5-point Likert scale with five items to evaluate the spokesperson's voice in terms of how pleasant, clear, correct, persuasive and credible it was, which was finally reduced to three items (see Table 1). In this case the respondents were also exposed to the spot one more time before evaluating the spokesperson.

Measures of advertising effectivenessThe measures of effectiveness used include the three levels of an individual's response to advertising toward a specific stimulus – namely cognitive, affective and conative. These are the measures commonly used in scientific research. Thus, to quantify the cognitive component we used unaided and aided recall for product category, brand and characteristics of the spot (Mantel and Kellaris, 2003; Beerli and Martín, 1999), as well as an audio recognition YES/NO test of the spots (Potter, 2006), reinforced with a security question. For the affective level the measures were liking, attitude toward the ad and attitude toward the brand, designed based on the previously validated scales. In order to evaluate the affective measures, the respondents were exposed to the radio spot before completing their evaluation. Lastly, to evaluate the conative level we used intention to donate following the pattern in the scales of purchase intention shown in Beerli and Martín (1999). These are the measures of effectiveness used as dependent variables and their definitive items (see Table 2):

- –

Intensity of unaided recall measured in a 5-point scale, from lower to higher level of recall depending on the quality of the recall of product category, brand and characteristics of the spot. The levels of unaided recall of product category, brand and some characteristic(s) of the spot were 43.5%, 5.1% and 29.4% respectively.

- –

Intensity of aided recall measured in a 4-point scale, from lower to higher level of recall depending on the quality of the recall of brand and characteristics of the spot. The levels of aided recall of the brand and some characteristic(s) of the spot when the respondents were suggested blood donation were 16.9% and 64.1% respectively.

- –

The level of recognition was measured using a 4-point scale based on the YES/NO recognition test of the product category and the YES/NO audio recognition of the different versions of the spot. We also used a 1 item, 5-point Likert scale to measure the security in response of the audio recognition. The level of verbal YES/NO recognition of the existence of a spot on blood donation was 89.8%, and the level of YES/NO audio recognition of the spot was 94.1%. In the case of audio recognition, the percentage of respondents who declared recognizing the spot with a high or very high level of security was 82.7%.

- –

Liking was measured using a 1 item, 5-point Likert scale, to indicate the intensity of liking toward the spot (Beerli and Martín, 1999):

- –

Attitude toward the ad was measured using a 20 item, 5-point Likert scale. The content validity of the scale is guaranteed, as the items were taken from the studies of Lavack et al. (2008), Bolls and Muehling (2007), Potter and Choi (2006), Miller and Marks (1992) and Sullivan (1990), all of whom have focused on radio advertising. The design has taken both components of attitude toward the ad into account: the evaluative and the affective component.

- –

Attitude toward the brand was measured using a 6 item, 5-point Likert scale. These items guarantee the validity of the construct, as they were developed based on the works on radio of Miller and Marks (1992) and Bolls and Muehling (2007).

- –

The results of the intended behavior were measured using a 1 item, 5-point Likert scale which showed the degree of willingness to donate blood after listening to the spot.

Definite items of the scales on measures of effectiveness.

| Measures of cognitive effectiveness | |||

| Intensity of unaided recall | |||

| 0 | Cannot recall anything | ||

| 1 | Can only recall product category (blood donation) | ||

| 2 | Can recall product category and one of the characteristics of the radio spot | ||

| 3 | Can recall product category and brand or several characteristics of the radio spot | ||

| 4 | Can recall product category and brand and one or several characteristics of the radio spot | ||

| Intensity of aided recall | |||

| 0 | Cannot recall anything on blood donation spot when mentioned | ||

| 1 | Can recall one of the characteristics of the spot when mentioning blood donation | ||

| 2 | Can recall the brand or several characteristics of the spot when mentioning blood donation | ||

| 3 | Can recall the brand and one or several characteristics of the spot when mentioning blood donation | ||

| Intensity of recognition | |||

| 0 | Does not recall having heard a spot on blood donation and does not recognize it when played again | ||

| 1 | Recalls having heard a spot on blood donation when mentioned, but does not recognize it when played again or does not recall having heard a spot on blood donation when mentioned but recognizes it when played again | ||

| 2 | Recall having heard a spot on blood donation when mentioned and then recognizes having heard it with no or little certainty | ||

| 3 | Recalls having heard a spot on blood donation when mentioned and then recognizes having heard it with some or great certainty | ||

| Measures of affective effectiveness | |||

| Attitude toward the ad | |||

| V20 | The ad is credible | V28 | The ad is dynamic |

| V21 | The ad is attractive | V29 | The ad is fun |

| V23 | The ad is informative | V32 | The ad is convincing |

| V25 | The ad is easy to understand | V34 | The ad is useful |

| V27 | The ad is nice | ||

| Attitude toward the brand | |||

| V40 | It is bad-It is good | V43 | The quality is bad–The quality is good |

| V41 | I do not like it at all-I really like it | V45 | It is not necessary–It is necessary |

We determined the population based on the target audience of the radio spot, namely both male and female aged 18–55, who are frequent radio listeners. By doing so, and according to the latest data of the EGM (AIMC-EGM, 2012) this target represents approximately 68% of the total radio audience in Spain. More specifically, the profile of this audience shows a slight difference in terms of gender (52.1% male vs. 47.9% female) and most are above 24 (11.5% aged 18–24; 28.7% aged 25–34; 31.9% aged 35–44; 28.0% aged 45–55). However, the final distribution of the obtained sample is very similar to the population (see Table 3).

Sample distribution.

| Characteristics | Theoretical sample | Real sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N | % | N | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 52.1 | 521 | 49.1 | 485 |

| Female | 47.9 | 479 | 50.7 | 500 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–24 | 11.5 | 115 | 17.6 | 174 |

| 25–34 | 28.7 | 287 | 28.6 | 282 |

| 35–44 | 31.9 | 319 | 24.6 | 243 |

| 45–55 | 28.0 | 280 | 29.1 | 287 |

| Education | ||||

| No studies | – | – | 0.9 | 9 |

| Primary education | – | – | 22.1 | 218 |

| Secondary education | – | – | 39.7 | 392 |

| Intermediate university degree | – | – | 14.9 | 147 |

| Higher university degree | – | – | 22.0 | 217 |

| Social class | ||||

| Lower | – | – | 7.4 | 73 |

| Lower-Middle | – | – | 25.5 | 252 |

| Middle | – | – | 31.9 | 315 |

| Upper-Middle | – | – | 24.1 | 238 |

| Upper | – | – | 6.7 | 66 |

| Total | 100 | 1000 | 100 | 987 |

The characteristics of our methodological process are (1) the use of a personal self-administered survey as an instrument to gather information; (2) a sample comprising 987 frequent radio listeners in the Canary Islands and the Community of Madrid, which means assuming a percentage error of ±3.18% for a confidence interval of 95.5%; (3) both the experiment and the filling of the questionnaire were conducted by a group of trained survey-takers, which had to select individuals among their own network of relationships, and (4) individuals were selected through non-probabilistic convenience sampling with a proportional affixation quota of gender and age (see Table 3) which were estimated theoretically based on the distribution of radio audience according to data from (EGM) and (5) the survey-respondents were exposed to the stimuli and had to fill in the questionnaire at their houses, so as to guarantee favorable listening conditions and the willingness to fill in the questionnaire.

As relevant data it is worth mentioning that 38.7% of the sample lived in the Canary Islands and 61.0% in Madrid. Out of the total sample only 21.2% were current donors and from the rest only 26.6% had previously donated blood. The profile of the real sample (see Table 1) shows a homogenous distribution between genders, a predominance of respondents aged 24 and above (82.3%), middle class citizens (81.5%) with no university studies (61.8%).

Before the individuals were exposed to the extract of programs we intended to test, the survey taker explained the hidden aim of the study. After that, the individuals listened to the 5min recording for a first time, in which we had inserted the spot we intended to test. Once heard, individuals were then asked to answer the questions on the questionnaire regarding unaided and aided recall. Then, the respondents were exposed exclusively to the spot of our study so as to answer the two questions on spot recognition included in the questionnaire. After answering these questions, the survey taker exposed the individuals to the spot one more time so they could give a suitable evaluation and answer the questions on affective and conative measures of effectiveness. Then, the survey takers played the recording one more time, emphasizing to the respondents that they had to pay special attention to the voice of the spokesperson. After that the respondents could answer the two questions on the evaluation of the spokesperson and their voice. Lastly, half of the sample who had been exposed to the versions with music then listened to the spot one more time. They were told that they had to pay special attention to the background music so they could evaluate on a scale the level of congruence between the music and the other stimuli in the spot. The experiment concluded by asking the respondents questions about their experience as donors and their sociodemographic data.

The distribution of the respondents of the different versions of the spot was homogenous, as shown in Fig. 2. The size of the sample exposed to each of the versions of the experimental variables was similar: spokesperson's gender (492–49.8% to male voices and 495–50.2% to female voices), spokesperson's vocal pitch (507–51.4% to low pitch and 480–48.6% to high pitch), spokesperson's accent (486–49.2% to local accent and 501–50.8% to standard accent) and style (458–46.4% to spots only with words and 529–53.6% to spots with words and background music).

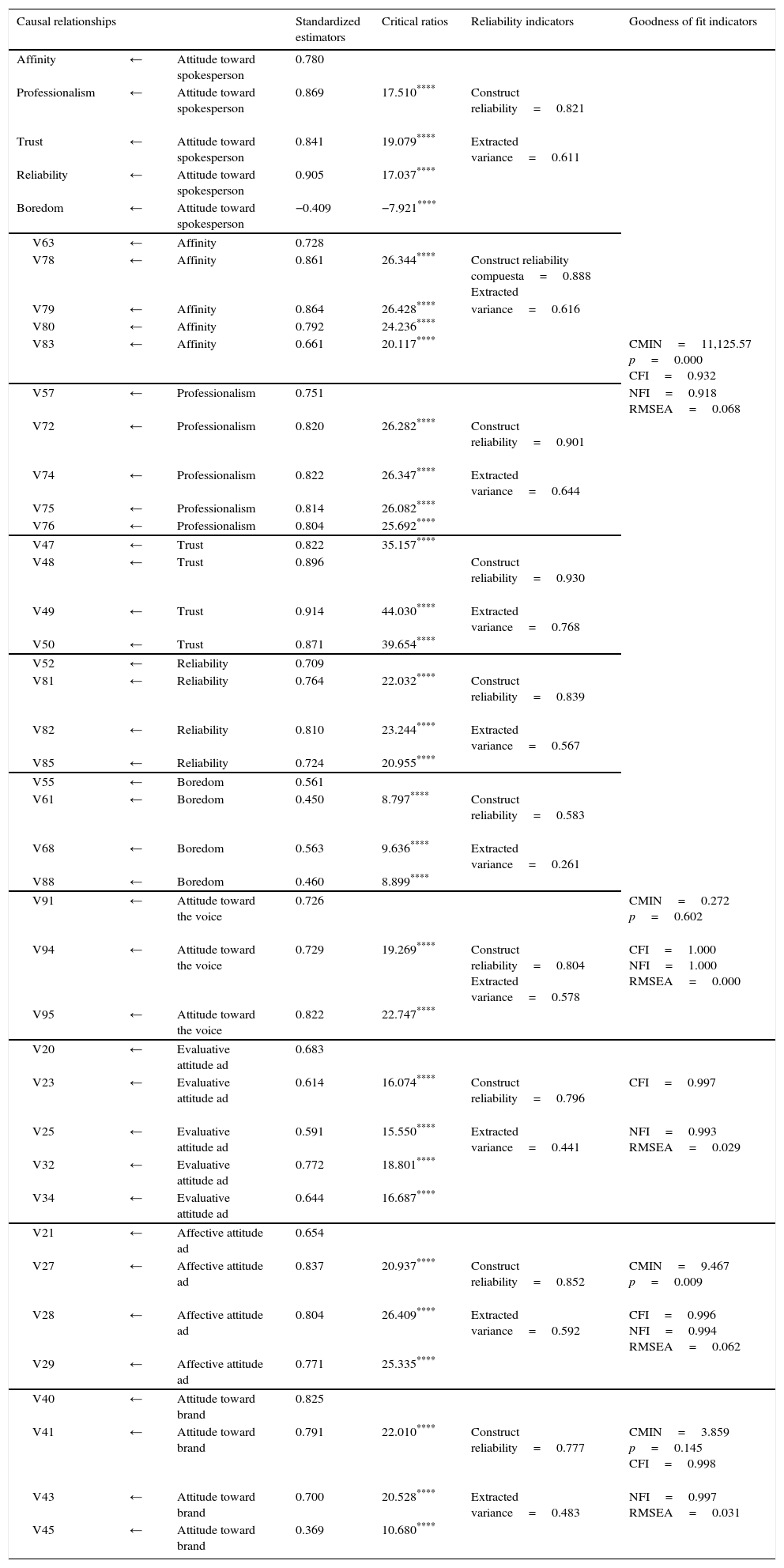

Analysis of the validity of measurement scalesBefore proceeding to contrast the hypotheses, the measurement scales of multiple items were analyzed for validity and reliability: attitude toward the spokesperson, attitude toward the spokesperson's voice, attitude toward the ad and attitude toward the brand. With this aim we first conducted an exploratory factor analysis to refine and determine the dimensional character of the scales; secondly, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to confirm the results, using linear structural equations, and lastly we analyzed the compound reliability coefficient and extracted variance to evaluate its reliability. Table 4 shows the results of the confirmatory factor analysis and the reliability measures, showing that the goodness of fit indicators are acceptable since all measures of fit, absolute, incremental and parsimony are within the limits of the recommended values in the literature, all the standardized regression weights show significant critical ratios above the recommended value of ±1.96 and that the reliability indicators are acceptable.

Results of the measure models.

| Causal relationships | Standardized estimators | Critical ratios | Reliability indicators | Goodness of fit indicators | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity | ← | Attitude toward spokesperson | 0.780 | |||

| Professionalism | ← | Attitude toward spokesperson | 0.869 | 17.510**** | Construct reliability=0.821 | |

| Trust | ← | Attitude toward spokesperson | 0.841 | 19.079**** | Extracted variance=0.611 | |

| Reliability | ← | Attitude toward spokesperson | 0.905 | 17.037**** | ||

| Boredom | ← | Attitude toward spokesperson | −0.409 | −7.921**** | ||

| V63 | ← | Affinity | 0.728 | |||

| V78 | ← | Affinity | 0.861 | 26.344**** | Construct reliability compuesta=0.888 Extracted | |

| V79 | ← | Affinity | 0.864 | 26.428**** | variance=0.616 | |

| V80 | ← | Affinity | 0.792 | 24.236**** | ||

| V83 | ← | Affinity | 0.661 | 20.117**** | CMIN=11,125.57 p=0.000 CFI=0.932 | |

| V57 | ← | Professionalism | 0.751 | NFI=0.918 RMSEA=0.068 | ||

| V72 | ← | Professionalism | 0.820 | 26.282**** | Construct reliability=0.901 | |

| V74 | ← | Professionalism | 0.822 | 26.347**** | Extracted variance=0.644 | |

| V75 | ← | Professionalism | 0.814 | 26.082**** | ||

| V76 | ← | Professionalism | 0.804 | 25.692**** | ||

| V47 | ← | Trust | 0.822 | 35.157**** | ||

| V48 | ← | Trust | 0.896 | Construct reliability=0.930 | ||

| V49 | ← | Trust | 0.914 | 44.030**** | Extracted variance=0.768 | |

| V50 | ← | Trust | 0.871 | 39.654**** | ||

| V52 | ← | Reliability | 0.709 | |||

| V81 | ← | Reliability | 0.764 | 22.032**** | Construct reliability=0.839 | |

| V82 | ← | Reliability | 0.810 | 23.244**** | Extracted variance=0.567 | |

| V85 | ← | Reliability | 0.724 | 20.955**** | ||

| V55 | ← | Boredom | 0.561 | |||

| V61 | ← | Boredom | 0.450 | 8.797**** | Construct reliability=0.583 | |

| V68 | ← | Boredom | 0.563 | 9.636**** | Extracted variance=0.261 | |

| V88 | ← | Boredom | 0.460 | 8.899**** | ||

| V91 | ← | Attitude toward the voice | 0.726 | CMIN=0.272 p=0.602 | ||

| V94 | ← | Attitude toward the voice | 0.729 | 19.269**** | Construct reliability=0.804 Extracted variance=0.578 | CFI=1.000 NFI=1.000 RMSEA=0.000 |

| V95 | ← | Attitude toward the voice | 0.822 | 22.747**** | ||

| V20 | ← | Evaluative attitude ad | 0.683 | |||

| V23 | ← | Evaluative attitude ad | 0.614 | 16.074**** | Construct reliability=0.796 | CFI=0.997 |

| V25 | ← | Evaluative attitude ad | 0.591 | 15.550**** | Extracted variance=0.441 | NFI=0.993 RMSEA=0.029 |

| V32 | ← | Evaluative attitude ad | 0.772 | 18.801**** | ||

| V34 | ← | Evaluative attitude ad | 0.644 | 16.687**** | ||

| V21 | ← | Affective attitude ad | 0.654 | |||

| V27 | ← | Affective attitude ad | 0.837 | 20.937**** | Construct reliability=0.852 | CMIN=9.467 p=0.009 |

| V28 | ← | Affective attitude ad | 0.804 | 26.409**** | Extracted variance=0.592 | CFI=0.996 NFI=0.994 RMSEA=0.062 |

| V29 | ← | Affective attitude ad | 0.771 | 25.335**** | ||

| V40 | ← | Attitude toward brand | 0.825 | |||

| V41 | ← | Attitude toward brand | 0.791 | 22.010**** | Construct reliability=0.777 | CMIN=3.859 p=0.145 CFI=0.998 |

| V43 | ← | Attitude toward brand | 0.700 | 20.528**** | Extracted variance=0.483 | NFI=0.997 RMSEA=0.031 |

| V45 | ← | Attitude toward brand | 0.369 | 10.680**** | ||

*p<0.10

**p<0.05

***p<0.01

As for the scale on attitude toward the spokesperson, given the high number of initial items, we decided to confirm each of the factors obtained in the exploratory factor analysis separately, using a confirmatory factor analysis. We obtained five dimensions that were labeled as affinity, professionalism, trust, reliability and boredom. The first three correspond to the dimensions of credibility obtained by Lalwani et al. (2005), and our dimension reliability includes some of the items Lalwani et al. include under the dimension trust. The last dimension, boredom, was included as it represents certain attributes that a spokesperson should never have. Once the five dimensions had been confirmed separately, we proceeded to confirm the construct attitude toward spokesperson using a second order model. The results, shown in Table 4, indicate that this model shows an acceptable goodness of fit, except the significance level of chi-square, as this statistic is sensitive to sample size and number of indicators (Hair et al., 1999).

Regarding the remaining constructs, namely attitude toward the spokesperson's voice, evaluative attitude toward the ad, affective attitude toward the ad and attitude toward the brand, the results show that they are one-dimensional constructs and that the scales are valid and reliable.

ResultsAnalysis on the influence of spokesperson's vocal pitch and gender on attitude toward spokesperson and attitude toward their voiceIn order to contrast hypotheses H1 and H2 regarding the effect of spokesperson's vocal pitch on attitude toward spokesperson and their voice, we conducted statistical tests on mean differences. Our aim was to check whether these differences existed between low pitch and high pitch voices both in the different dimensions of the construct attitude toward spokesperson and in the global construct, as well as in attitude toward their voice. The results (see Table 5), which allow us to accept H1 and H2, show what we expected: low pitch voices generate a more positive attitude toward the spokesperson and their voice. Similarly, these results show that the differences in attitude toward the spokesperson are associated with the dimensions regarding professionalism, trust and the reliability the spokesperson transmits.

Influence of spokesperson's vocal pitch and gender on attitude toward spokesperson and attitude toward spokesperson's voice.

| Dimensions and/or constructs | Total | Male | Female | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | t | Low | High | t | Low | High | t | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Affinity | 2.965 (0.896) | 2.948 (0.826) | 0.304 | 2.719 (0.937) | 2.993 (0.777) | 3.525**** | 3.195 (0.791) | 2.899 (0.875) | 3.914**** |

| Professionalism | 3.511 (0.869) | 3.212 (0.901) | 5.293**** | 3.373 (0.879) | 3.195 (0.851) | 2.274** | 3.640 (0.841) | 3.229 (0.955) | 5.048**** |

| Trust | 3.482 (1.024) | 3.210 (1.086) | 4.038**** | 3.260 (1.066) | 3.302 (1.047) | 0.438 | 3.688 (0.941) | 3.111 (1.120) | 6.207**** |

| Reliability | 3.388 (0.746) | 3.151 (0.793) | 4.812**** | 3.293 (0.743) | 3.101 (0.786) | 2.784*** | 3.476 (0.739) | 3.206 (0.798) | 3.876**** |

| Boredom | 2.526 (0.833) | 2.509 (0.809) | 0.328 | 2.787 (0.840) | 2.410 (0.747) | 5.249**** | 2.283 (0.749) | 2.615 (0.861) | 4.572**** |

| Attitude toward spokesperson | 3.450 (0.901) | 3.217 (0.927) | 3.943**** | 3.221 (0.906) | 3.253 (0.853) | 0.392 | 3.668 (0.843) | 3.179 (1.001) | 5.785**** |

| Attitude toward the voice | 3.273 (1.006) | 3.069 (1.036) | 3.123*** | 3.023 (1.021) | 3.149 (1.022) | 1.362 | 3.501 (0.938) | 2.983 (1.046) | 5.794**** |

On the other hand, given that the spokesperson's gender can determine the effect of voice pitch on these two attitudinal variables, as indicated in H3 and H4, we conducted the same analysis as before but distinguishing between male and female spokespersons. The results in Table 5 reveal that (1) among male spokespersons there are no differences in attitude toward the spokesperson or their voice, although we do observe that low pitched voices transmit more professionalism and reliability and (2) among female spokespersons there are differences both in attitude toward the spokesperson and also toward their voice; the female spokesperson with the lowest pitch obtained the highest ratings in all dimensions and constructs analyzed. In addition, to analyze the interaction effect of spokesperson's vocal pitch and gender we conducted a variance analysis with two factors; the interaction was significant for affinity (F=27.619; p≤0.001), professionalism (F=4.275; p≤0.039), trust (F=21.593; p≤0.001), boredom (F=48.173; p≤0.001), attitude toward spokesperson (F=19.994; p≤0.001) and attitude toward their voice (F=25.007; p≤0.001). These results allow us to accept both hypotheses.

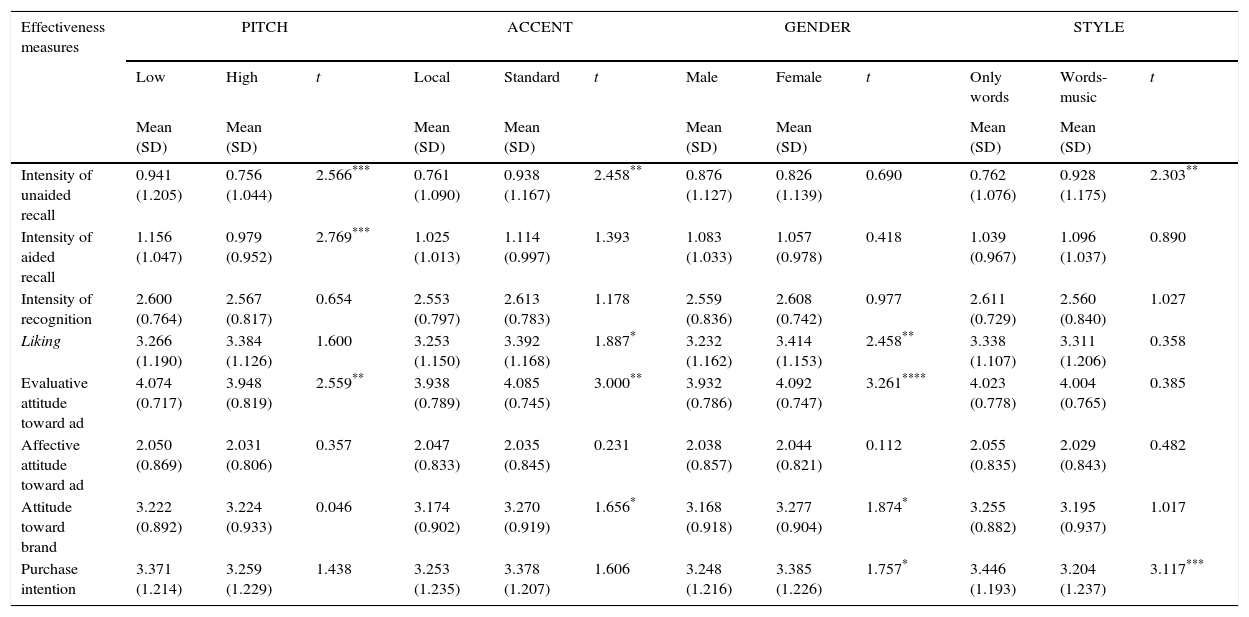

Analysis of the effect of vocal pitch on advertising effectivenessThe three hypotheses H5a, H5b and H5c intend to evaluate the influence of spokesperson's voice pitch on the different measures of advertising effectiveness used in this study, which have been grouped into three large categories: cognitive, affective and conative. To contrast these hypotheses we conducted an analysis on mean differences to check whether there were significant differences when the voice pitch was low or high on levels of unaided and aided recall, recognition, liking, on both components of attitude toward the ad, on attitude toward the brand and on intention to donate blood. The results (see Table 6) show that (1) the intensity of unaided and aided recall is higher when the voice pitch is low and there are no differences in the intensity of recognition, although the intensity is higher with low pitch. These results partially support H5a; (2) among the affective measures of effectiveness, there is only a significant difference in the evaluative component of the ad; thus results do not allow totally supporting H5b and, (3) intention to donate is not greater or smaller in the spots with low pitch, thus we reject H5c. These results allow us to state that voice pitch affects spot effectiveness as low-pitched voices generate better results.

Influence of spokesperson's vocal pitch, accent, gender and style on advertising effectiveness.

| Effectiveness measures | PITCH | ACCENT | GENDER | STYLE | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | t | Local | Standard | t | Male | Female | t | Only words | Words-music | t | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||||

| Intensity of unaided recall | 0.941 (1.205) | 0.756 (1.044) | 2.566*** | 0.761 (1.090) | 0.938 (1.167) | 2.458** | 0.876 (1.127) | 0.826 (1.139) | 0.690 | 0.762 (1.076) | 0.928 (1.175) | 2.303** |

| Intensity of aided recall | 1.156 (1.047) | 0.979 (0.952) | 2.769*** | 1.025 (1.013) | 1.114 (0.997) | 1.393 | 1.083 (1.033) | 1.057 (0.978) | 0.418 | 1.039 (0.967) | 1.096 (1.037) | 0.890 |

| Intensity of recognition | 2.600 (0.764) | 2.567 (0.817) | 0.654 | 2.553 (0.797) | 2.613 (0.783) | 1.178 | 2.559 (0.836) | 2.608 (0.742) | 0.977 | 2.611 (0.729) | 2.560 (0.840) | 1.027 |

| Liking | 3.266 (1.190) | 3.384 (1.126) | 1.600 | 3.253 (1.150) | 3.392 (1.168) | 1.887* | 3.232 (1.162) | 3.414 (1.153) | 2.458** | 3.338 (1.107) | 3.311 (1.206) | 0.358 |

| Evaluative attitude toward ad | 4.074 (0.717) | 3.948 (0.819) | 2.559** | 3.938 (0.789) | 4.085 (0.745) | 3.000** | 3.932 (0.786) | 4.092 (0.747) | 3.261**** | 4.023 (0.778) | 4.004 (0.765) | 0.385 |

| Affective attitude toward ad | 2.050 (0.869) | 2.031 (0.806) | 0.357 | 2.047 (0.833) | 2.035 (0.845) | 0.231 | 2.038 (0.857) | 2.044 (0.821) | 0.112 | 2.055 (0.835) | 2.029 (0.843) | 0.482 |

| Attitude toward brand | 3.222 (0.892) | 3.224 (0.933) | 0.046 | 3.174 (0.902) | 3.270 (0.919) | 1.656* | 3.168 (0.918) | 3.277 (0.904) | 1.874* | 3.255 (0.882) | 3.195 (0.937) | 1.017 |

| Purchase intention | 3.371 (1.214) | 3.259 (1.229) | 1.438 | 3.253 (1.235) | 3.378 (1.207) | 1.606 | 3.248 (1.216) | 3.385 (1.226) | 1.757* | 3.446 (1.193) | 3.204 (1.237) | 3.117*** |

Hypotheses H6a, H6b and H6c were contrasted with an analysis on mean differences. Our aim was to check whether there were significant differences in the various measures of effectiveness when the accent was local (Canarian accent) or when the accent was standard. The results (see Table 6) indicate that (1) spots using standard accent have higher levels of recall and recognition, although there are only significant differences in the first measure of cognitive effectiveness, thus we partially accept H6a; (2) there are significant differences in liking, in the evaluative attitude toward the ad and the brand, although in attitude toward the brand the significance level is 9.8%, and spots with standard accent are better rated. These results allow partially accepting H6b, and (3) accent does not generate more or less intention to donate, thus rejecting H6c. These results allow us to state that accent has an influence on effectiveness.

Analysis of the influence of spokesperson's gender on advertising effectivenessTo contrast the three hypotheses H7a, H7b and H7c we conducted the same analysis as previously. The results (see Table 6) indicate that (1) the gender of the spokesperson does not have an effect on the cognitive effectiveness of radio spots, thus rejecting H7a, as male voices do not generate greater cognitive effectiveness; (2) in spots featuring a female spokesperson, affective effectiveness is greater in three out of the four measures used; thus we must reject H7b that suggested male voices were more effective on an affective level and (3) female spokespersons can generate greater intention than men when it comes to donating blood, thus we must reject H7c. These results regarding the variable gender show the opposite of what we expected.

Analysis of the influence of music on advertising effectivenessTable 6 shows the results of the tests on mean differences to check whether music affects advertising effectiveness on its three levels. The conclusion is (1) the format combining word and music is the most effective on a cognitive level only in terms of unaided recall, thus we partially accept H8a; (2) including background music has no influence on effectiveness on an affective level, thus rejecting H8b, and (3) the format without music generates a greater intention to donate blood, thus we also reject H8c. Therefore, taking these results into account we conclude that the use of music is not always more effective. These results are probably due to the lack of congruence between the music and blood donation. In fact, the respondents exposed to the spot with music scored on a scale from 1 to 5 that music was not appropriate for the message, it did not fit the message, it was not relevant to the topic of the spot, it did not fit with blood donation and it was incongruent.

ConclusionsThe underuse of the radio's communicative potential in its commercial perspective and the scarce academic investigation on its effectiveness, excluding some laboratory studies on inappropriate populations, is what has led us to conduct this study. The main aim was to analyze the advertising effectiveness of the voice of spokespersons as one of the main resources of radio language. The study has connected the evaluation of the spokesperson and their voice with its influence on the cognitive, affective and conative levels on the audience with a non-gender imaged product.

In the present study we have designed an investigation procedure that allows integrating variables that have otherwise been studied separately in academic research. Our experiments combined the use of male voices vs. female voices, low vocal pitch vs. high vocal pitch, local accent vs. standard accent and the use of only word vs. the use of word and background music.

Based on the results, selecting a spokesperson for a radio spot is one of the most important decisions faced by an advertiser in this media, given the content and the importance of the dimensions identified to evaluate a spokesperson and the differences identified in the levels of effectiveness depending on the use of the features of the voice we analyzed.

We have reached the conclusion that attitude toward the radio spokesperson is multidimensional and in those dimensions regarding professionalism, trust and reliability low-pitched voices show significant differences compared to high pitched ones. Similarly, the moderating role of gender is very significant in female voices, where low pitched voices have been the best rated in all dimensions as well as the voice itself, regarded as that with greatest affinity, professionalism, trust and reliability and the least boring. On the contrary, for male spokespersons low-pitched voices only stand out in their ratings of professionalism and trust, with no significant differences in the two global constructs of attitude toward the spokesperson and their voice.

Regarding the influence of vocal pitch on cognitive effectiveness, the results show that low pitched voices generate higher levels of unaided and aided recall. In terms of affective effectiveness, we only observed a better attitude in listeners in the evaluative component of attitude toward the ad in low-pitched voices. This result is in line with those studies showing that low-pitched voices generate a better evaluative attitude due to their ability to generate greater credibility and persuasion, mainly in informative-descriptive message as the one in our study.

The variable gender is probably the most widely studied resource of the voice in terms of is acoustic qualities, although its advertising effectiveness does not receive as much attention and some results are contradictory. Our results further strengthen that the prevalence of the male gender is by no means justified. As other previous studies have shown, although spokesperson's gender has no influence on advertising recall with non-gender imaged products, we observe a significant influence of gender on achieving the advertising aims related to the evaluation of the ad, attitude toward the brand and behavior when the spokesperson is female. In other words, the effectiveness of female voices is greater than male ones when the advertising aims to have an emotional link on a brand and the ad and when the advertiser's desired response is to modify or trigger a particular behavior.

As for the influence of local accent, the lack of academic literature was precisely one of the reasons for including this variable in our study. The results provide empirical evidence on the better rating of standard accent over local accent (Canarian) in cognitive and affective measures, in terms of liking, in the evaluative attitude toward the ad, and less significantly in the attitude toward the brand. The spot with standard accent was better rated, although the sample comprised individuals from the Canary Islands and Madrid. A possible explanation could be that the Canarian audience is used to standard accent in advertising (even for local brands), whereas as listeners from Madrid are not used to Canarian accent. In addition, the negative evaluations reflect a negative attitude toward this accent regarded as different, perhaps due to prejudices and cultural evaluations, as a high percentage of listeners from Madrid identified the Canarian spokespersons as Latin American. Similarly, the concept of diglossia would explain that the radio spots with Canarian accent were judged as less appropriate, credible or serious. This situation also occurs in the place of origin of this accent, so in the Canary Islands there is also a tendency to use standard accent. These perceptions can have an influence on advertising effectiveness, as the results on a cognitive level are consistent with the worse evaluation of the local accent (Canarian accent). The sample that listened to the spot with Canarian accent showed lower levels of unaided and aided recall of the message and the brand. However, on a conative level we observe that accent has no effect on intention to donate. As previously seen on the effect of vocal pitch on a conative level, the low percentage of donors in the sample (21.2%) and the principles of advertising planning perhaps justify the lack of influence of accent on a conative level, as achieving the intended behavior requires a greater frequency of contacts and not just being exposed to an ad once, as was the case in this study.

The high presence of music in radio spots led us to analyze and contribute evidence on its effectiveness that justify the advertiser's use of music. Although the use of music has shown no significant differences in most measures of effectiveness, the positive influence of music on unaided recall and its opposite influence on a conative level, made us consider the need to plan this creative element strategically, more than simply to avoid silence. Although the best results on unaided recall show the ability of this resource to gain or to increase the attention of the listeners, as suggested by Lavack et al. (2008), it seems that it is not useful to add evaluative or emotional meaning to the ad, and above all it can have a negative effect on intention.

Managerial implicationsThis study provides recommendations for the creative execution of radio advertising campaigns. The main practical implication focuses on selecting spokespersons with the characteristics that will improve their evaluation and the advertising effectiveness on specific audiences. Similarly, one should consider the ability of these resources in achieving the advertising aims related to the stages in the lifecycle of a product.

One of the reasons why the effectiveness of spokesperson's gender has been studied is the confirmed prevalence of male announcers in radio advertising, regardless of the gender image of the advertised product. However, the results of our study show that the underuse of female voices is limiting the optimization of this resource. Female voices are particularly useful for advertisers who compete in product categories with a non-gender imaged product and in mature markets, where it is vital to strengthen and generate selective audiences that understand the differential attributes between brands, since female voices have a greater ability to act on evaluative attitude toward the ad and the brand as well as on behavior.

From a methodological perspective, we have used measures of unaided and aided recall of product, brand and characteristics of the ad to quantify the cognitive component. Several studies highlight the need to use unaided and aided recall simultaneously to measure the cognitive effect of advertising (Moorman et al., 2007), because as De Pelsmacker et al. (2005) suggest, unaided recall is a stronger measure of memory and thus more difficult to obtain than aided recall. Given the characteristics of unaided recall, we can infer the special ability of low-pitched voices and the absence of local accent to act on a more complex component of recall, and how useful this can be for advertisers with new brand and product categories and/or for those for whom notoriety is the main aim of their advertising campaigns.

On the other hand, an added value in this line of investigation is understanding the relationship between cognitive, affective and conative effectiveness in the same sample and using the same stimuli. Our results show, for instance, the inverse relationship between cognitive and conative effectiveness based on the use of music in a radio spot. So, although the presence of music generates higher levels of unaided recall, this generates less intention than a spot using only words.

Our methodological design aimed to overcome the limitations identified in the literature. On the one hand, we studied a wide sample of microstructural characteristics in radio advertising, trying to identify the possible links between them, as is the case of spokesperson's gender and vocal pitch. On the other hand, we explored our aims using a wide sample representative of the real radio audience, in terms of gender and age, as opposed to samples of students commonly used in investigations. Thus we provide empirical evidence that allows an advertiser to make the main decisions on this resource in a more reliable manner. In addition, the stimuli were designed so as to avoid the bias identified in the literature regarding its duration, content, style, spokesperson's diction and articulation and professionalism. We also isolated certain effects such as the effect of spokesperson's voice on effectiveness, the relationship between the type of product and the target audience, their gender image or how appropriate the background music is for the product and message.

LimitationsBased on the information provided using the methodological criteria mentioned above, we have detected the existence of some limitations. Firstly, given that we only used one spot as our advertising stimulus the results of this study may only be extrapolated to radio spots with similar characteristics to the one we used, such as informative spots advertising non-gender imaged products and featuring only one voice. Secondly, the use of only one musical piece could also condition the results, since aspects such as musical style and the congruency of music with the product and the message could play a moderating role on how music influences the effectiveness of the radio spot. In fact, Dilman Carpentier (2010) verified that music congruency is a relevant factor that should be taken into account when studying effectiveness. Therefore, our results could be conditioned by the low evaluations given by the sample expressing the inappropriateness of the music we used for the product of blood donation. Once again, based on this result we must highlight the strategic and delicate nature of this decision given its high levels of subjectivity and the need to pretest how relevant and appropriate the music is for the product and the message.

Future investigationBased on the potential of the mentioned limitations and given that in certain variables cognitive effectiveness has been shown to work differently to conative effectiveness, one should further analyze the origin of these results for each level of response. The results presented in our paper have multiple implications that need a more specific analysis that exceed the general aim of our study. In the short run, future lines of investigation will be more precise considering other variables listed in the wide database created such as the individual's implication and experience with donation, donation inhibitors, certain classification variables like age, gender or geographical original of the individual in the sample. We have also highlighted that one of the variables less developed in academic research is spokesperson's accent. An example of an immediate line of investigation is analyzing the results obtained and corroborating the level of cognitive effectiveness distinguishing the listener's community of origin and the local accent tested in this sample. Maybe by doing so we can better observe the influence of accent and if there are direct prejudices toward the studied accent. On the other hand, the limitations of this study also give rise to new lines of investigation that overcome the methodological determining that would allow to corroborate these results with other types of spot and different characteristics of musical pieces.