We address the influence of directors who represent institutional investors in three aspects of board compensation policies: level of compensation, composition, and performance sensitivity. We differentiate pressure-sensitive directors (i.e., with business links) and pressure-resistant directors (i.e., without business links). Our results show that pressure-resistant directors decrease total board compensation and its fixed proportion, whereas they increase the variable proportion of total remuneration and the pay-for-performance sensitivity. By contrast, pressure-sensitive directors offer the opposite results. These findings are consistent with the view that institutional investors are not a homogeneous group and that pressure-resistant directors fulfill a more thorough monitoring role.

Corporate compensation schemes have been a high priority issue in the agenda of corporate governance reforms. In an attempt to improve corporate governance in public firms and to mitigate potential conflicts of interest, the European Commission recently issued several recommendations (2009/384/EC; 2009/385/EC) to enhance appropriate compensation policies, more detailed disclosure requirements, and a higher level of control for independent directors and shareholders within the pay setting process.

In this debate regarding appropriate compensation policies, 90% of institutional investors believe that corporate executives are overpaid (Brandes et al., 2008). This perception has led some institutional investors to give up their traditional passive role and become actively engaged in the compensation decisions at their portfolio firms (Bushman and Smith, 2001; Hartzell and Starks, 2003). As institutional investors have emerged as a significant group of shareholders with the incentives and the capabilities to check managerial power, these investors also exercise their influence on the compensation schemes of their invested firms (Parrino et al., 2003).

The literature has found that institutional investors influence both the level and the structure of CEO pay in accordance with shareholder interests, which may be in conflict with the interests of CEOs (David et al., 1998; Hartzell and Starks, 2003). But, although prior research provides significant insights on the relationship between institutional investors’ ownership and compensation, it has not yet addressed the effect of these shareholders as directors and the impact of their different nature on compensation policies.

With the notable exceptions of Hempel and Fay (1994), Boyd (1996) and Cordeiro et al. (2000), most previous literature focuses on CEO and executive compensation, so little is known about the determinants of the pay of other senior personnel. However, rapid growth in director compensation has caused a big controversy, since directors serving on the compensation committee can determine the level and mix of their own compensation packages (Cordeiro et al., 2000). This fact has led to potential conflicts of interests, different to the conflicts with managers, who do not set their own salaries. Indeed, according to Dalton and Daily (2001) the stock based compensation for directors is even more contentious than similar practices for officers.

The presence of directors appointed by institutional investors on the board is rising across countries and, accordingly, these institutions are becoming more influential in the corporate governance. Heidrick and Struggles (2011) find that, although directors appointed by institutional investors only account for 2% of British firms directorships, they account for 40% of directorship in Spain, 35% in Belgium, and 22% in France. Moreover, due to an alleged lack of efficiency of independent directors in European countries, some authors highlight that the supervising role in these environments is actually played by directors appointed by institutional investors (Sánchez Ballesta and García Meca, 2007). Given the widespread importance of institutional investors, a better understanding how their presence on boards affects their own compensation schemes is clearly needed, especially in civil-law countries where these directors are taking up an increasingly active role in their firms’ corporate governance.

We study the impact of institutional directors on two aspects of remuneration policy: composition and sensitivity. We also check whether institutional directors have a significant moderating effect on the relation between performance and board remuneration. The literature shows that institutional investors do not act as a monolithic group in firm governance (Almazán et al., 2005; Cornett et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2007; Choi et al., 2012). Accordingly, we propose that the type of business relation between firms and institutional investors is the key to describing the role of institutional directors. We therefore study the relation between remunerations and institutional directors, making a distinction between the institutional investors who keep business relations with the firm on whose board they sit and the institutional investors whose business activity is not related to the company in which they hold a directorship.

We use a sample of Spanish listed firms between 2004 and 2010. Spain is likely the best paradigm to study the effectiveness of institutional directors for two main reasons. First, Spain is the European country with the highest presence of institutional investors on the boards of large firms (Bona et al., 2011; Crespí and Pascual, 2012). Second, the Spanish financial system is bank oriented. Banks play an outstanding role both as creditors and blockholders. Banks also appoint a significant proportion of directors to the boards of their client firms.

Our results suggest that maintaining business ties between firms and institutional investors affects the role of the institutional investors. Directors appointed by pressure-resistant investors serve a monitoring role that mitigates the agency problem between shareholders and manager. Coherent with their disciplinary role, pressure-resistant directors increase the relative weight of the variable compensation, decrease the proportion of fixed compensation, and induce compensation packages sensitive to performance. These findings are consistent with the view that differences exist between these two types of directors and that pressure-resistant directors fulfill a more thorough monitoring role.

We make several contributions to the literature. First, we provide new evidence on the effects of directors appointed by institutional investors on remuneration policy in a way that is difficult to capture in the US or UK context, where this kind of director is less prevalent. Existing studies on the effects of institutional investors are commonly based in the framework of the conventional US/UK model of corporate control and therefore, in general, focus on institutional investors solely as shareholders. Second, we provide new evidence on the effect of board composition on director remuneration. Although managerial compensation has been often analyzed, directors’ pay has only recently sparked an intense debate in Europe. The wave of corporate scandals has renewed concerns about the effectiveness of board monitoring and the high compensations that directors’ receive. Finally, our examination of whether institutional investors’ presence on boards of different types of institutions, such as banks or investment funds, leads to observable differences in remuneration policy can provide new insights on the heterogeneity in monitoring costs across institutional investors, which, in turn, has important implications for the debate over the proper degree of institutional involvement in corporate governance.

Theoretical foundations and hypotheses developmentTheoretical backgroundAlthough small shareholders can vote with their feet if they do not agree with the performance or actions of managers, institutional investors find it difficult to offload their substantial investments without negatively impacting stock prices. Given the cost and difficulty of selling their shareholdings, institutions are motivated to pressure management into taking actions that benefit outside shareholders. Institutional investors then provide a strong incentive to promote company activities that increase the firm's value and thus the value of their own investments (Jensen and Warner, 1988). Two such actions may moderate excessive pay and encourage pay-for-performance reward systems. Hartzell and Starks (2003) report that institutional ownership concentration is positively related to the pay-for-performance sensitivity of executive compensation and negatively related to the level of compensation, even after controlling for firm size, industry, investment opportunities, and performance.

The concentrated ownership structure of European countries, as Spain, may lead result in other conflicts of interests such as o the so-called principal–principal agency conflicts (Hartzell and Starks, 2003; Huddart, 1993; Shleifer and Vishny, 1986; Young et al., 2008). According to this self-serving perspective, institutional investors, acting either as directors or in collusion with managers, may engage in tunneling activities and in the expropriation of wealth from minority shareholders (Johnson et al., 2000; Renders and Gaeremynck, 2012; Shan, 2013). Thus, instead of imposing an efficient control on managerial discretion, institutional shareholders may abuse their position of dominant control at the expense of the other stakeholders to expropriate rents from the noncontrolling shareholders (Harris and Raviv, 1988; Shleifer and Vishny, 1997).

From the agency theory perspective, the board of directors can work as an information system for external stakeholders to monitor insiders behavior. In this context, directors compensation is then an important incentive mechanisms that shape director behavior. According to Davis and Stobaugh (1995) director compensation should fulfill several goals: (a) motivate them to align their interests with shareholders; (b) cover responsibility and liability risk; (c) be consistent with transparency in director compensation setting. A key issue therefore is whether directors are being compensated in a way that motivates them to put effort and make decisions that maximize the return of the shareholders they represent to (Cordeiro et al., 2000). Then, although nonexecutive directors and, specifically, those appointed by institutional investors are charged with looking after the interests of shareholders, there are reasons to question their effectiveness. Conflicts of interests appear where directors serving on the compensation committee determine the level and mix of their own compensation packages (Cordeiro et al., 2000). In exchange for excessive compensation, directors may be more lax in discharging their assigned monitoring and oversight functions leading them to expropriation activities. According to Chen et al. (2013), these potential conflicts of interest and related outcomes may ultimately serve to erode any anticipated benefits of director compensation.

When analyzing the consequences of directors appointed by institutional investors, we must not consider them as a homogeneous group. The differences across institutional investors are not only legal or regulatory but also vary in terms of investment strategy and the incentives and resources to gather information and to engage in corporate governance (Bennett et al., 2003). Almazán et al. (2005), Borokhovich et al. (2006), Bushee (1998), Ferreira and Matos (2008) and Ramalingegowda and Yu (2012) have shown that certain types of, but not all, institutional investors have an asymmetric influence on corporate issues such as antitakeover amendments, R&D investment decisions, profitability, and earnings conservatism.

Along this line, two main groups of institutional directors can be differentiated: pressure-sensitive institutional investors who maintain business with the firm in which they invest – basically, banks and insurance companies – and pressure-resistant institutional investors with no potential business links – basically, investment funds and pension funds. According to Almazán et al. (2005), the costs of monitoring differ across both groups, with the potentially active group (i.e., the pressure-resistant investors) having lower costs. Consistent with this classification, we differentiate between pressure-sensitive directors (i.e., representing pressure-sensitive institutional investors) and pressure-resistant directors (appointed by pressure-resistant institutional investors).

Hypotheses developmentBanks and insurance companies face different regulatory, legal, and competitive environments than investment funds. David et al., 1998, Almazán et al., 2005 and Shin and Seo (2011) suggest that institutional investors’ fiduciary responsibilities, conflicts of interest, and asymmetric information interact with each other to determine jointly the influence of institutional investors on remuneration. They argue that pressure-resistant institutional investors are less likely to suffer from conflicts of interest arising from business relationships and, thus, more likely to engage actively in monitoring. Consequently, directors who represent institutions without business relations can use their vote power to oppose preferences for more generous compensation. Nevertheless, since compensation schemes are usually viewed as an incentive mechanism, one could assume that more generous compensation packages could appeal more talented directors. As a consequence, the question about the relation between the different types of institutional directors and the compensation level arises. We address this issue in an exploratory approach and run preliminary analyses to check whether pressure-resistant or sensitive directors are related to higher or lower director compensation.

Critics have voiced concerns that directors’ compensation packages have not been closely tied to firm performance (Bebchuk and Fried, 2004). As an example, Bebchuk and Grinstein (2005) argue that executive pay has increased far beyond levels that can be explained by the growth in firm size and the performance observed over the 1993–2003 period. Joining compensation to performance helps align board interests with shareholder interests. Explicit ties between directors’ wealth and the firm's stock price provide directors with a strong incentive to increase firm value. Consequently, directors’ remuneration should be positively related to firm performance. However, due to the conflicts of interests, we posit that directors appointed by pressure-resistant institutional investors will be more motivated to strengthen the relation between performance and board payments than directors appointed by pressure-sensitive institutional investors. The higher costs of monitoring of pressure-sensitive directors, related to differences in their legal, regulatory and competitive environments as well as the likelihood of current or future business dealing with the firms they own, may weaken the relationship between firm performance and board compensation.

This intuition is consistent with Almazán et al. (2005), who find that the link between performance and managerial compensation increases with the concentration of active institutions’ ownership (pressure resistant) but is not significantly related to the concentration of passive institutions’ ownership (pressure sensitive). Accordingly, we hypothesize that a similar relation should hold for institutional directorships:H1 Pressure resistant (pressure-sensitive) institutional directors positively (negatively) moderate the relationship between firm performance and board remunerations.

Given this discussion, pressure-resistant directors should be able to counteract managerial dominance and to align compensation schemes with shareholders’ preferences. Directors’ remuneration packages have several components and vary widely across firms. Some companies reimburse directors’ expenses for attending meetings but provide no additional compensation. Other companies pay a uniform annual cash retainer plus per-meeting fees. Besides cash compensation, firms may provide restricted stocks or stock options to committee members.

We consider short-term incentives including base salary and long-term incentives including stock options, long-term incentive plans, and additional benefits. A number of good reasons exist to explain why long-term incentives are an effective pay component (Bryan et al., 2000; Goergen and Renneboog, 2011). First, they provide the most direct link between firm performance and pay. Therefore, they may incentivize directors to work hard and to make shareholder-oriented decisions. Second, long-term incentives may enable the firm to bring valuable human capital to the board and to ensure the loyalty of the incumbent directors. However, according to the European Commission variable pay schemes have become increasingly complex and have led to excessive remuneration and manipulation (EUCGF, 2009). This finding suggests that board-incentive pay is a two-edged sword: on the one hand, it can align the interests of controlling and minority shareholders; on the other hand, it can induce undesirable behavior and overly generous board pay (Shin and Seo, 2011).

We posit that the incentives of institutional directors to monitor composition board pay depend on the conflicts of interest that the institutional directors face. These conflicts are more pronounced when institutional investors have business ties with the firm. Due to the lower conflicts of interests and their interest in aligning board interests with shareholder interests, we posit that directors appointed by pressure-resistant institutional investors will prefer long-term incentive plans than directors appointed by pressure-sensitive ones. A large stock-based component that ties board pay to firm performance is believed to increase board pay risk and help align the directors’ interest with those of shareholders. Accordingly, we hypothesize that pressure-sensitive directors will prefer to retain control over their pay by receiving a higher proportion of fixed compensation and a lower proportion of variable compensation. The higher conflicts of interests, their risk aversion as lenders and their incentives to minimize the probability of default may explain these expectations. Consequently, our second hypothesis is stated as follows:H2 Directors representing pressure-resistant institutional investors are negatively related to board’ fixed salary (short-term compensation) and positively related with their variable compensation (long-term incentives), compared to directors representing pressure-sensitive investors.

One of the most often used mechanisms to tie the incentives of insiders to shareholders’ interests is pay-for-performance schemes (Jensen and Murphy, 1990). Although there are not any evidence in this context regarding board remuneration as a whole, David et al. (1998) and Almazán et al. (2005) find that pressure-resistant institutional investors are more likely than pressure-sensitive institutional investors to influence CEO pay in accordance with shareholder preferences. More specifically, the stake of these institutional investors is negatively associated with the level of CEO pay but positively associated with pay-for-performance sensitivity.

We suggest that directors appointed by banks and insurance companies will have more pronounced conflicts, leading them to compromise their role in monitoring director pay. Thus, pressure-sensitive directors will be less interested in tying directors’ pay to firm performance. Conversely, pressure-resistant directors have more ability to use their position to discipline other directors preferences and will therefore be more prone to link the compensation packages to the firm's performance.H3 Directors representing pressure-resistant institutional investors will increase board remuneration sensitivity more than directors representing pressure-sensitive investors.

Our sample is drawn from the population of Spanish nonfinancial firms listed on the Spanish Stock Exchange during 2004–2010. We exclude financial companies both because they are under special scrutiny by financial authorities that constrain the role of their board of directors and because of their special accounting practices. We obtain our data from two databases. Financial information and firms’ market value come from the Amadeus database.1 Corporate governance information is collected from the annual corporate governance reports that all listed companies must publish since 2003. These corporate governance reports do not provide individualized information about the compensation of each director but do provide the total aggregate compensation of the board members and its distribution among the different components.

We build an unbalanced panel of 627 firm-year observations from 162 firms. Roughly, our sample accounts for more than 95% of the capitalization of Spanish nonfinancial firms. The panel is unbalanced because during this period some firms become public and other firms delist as a consequence of mergers and acquisitions. Nevertheless, the estimations based on unbalanced panels are as reliable as those based on balanced panels (Arellano, 2003).

VariablesWe define four dependent variables that are consistent with each one of our hypotheses. RETRIB is the average annual compensation of each director, defined as the total compensation of the whole board of directors divided by the number of directors. FIXCOMP is the fixed proportion of the compensation, defined as the quotient between the total fixed compensation and the total compensation of the whole board of directors. VARCOMP is the variable component of the compensation, defined as the ratio of total variable compensation to the total compensation of all the board members.2 SENSITIVITY is the sensitivity of the average compensation of the directors to changes in firm performance, which is operationalized as the variation in the compensation of the board relative to the variation of return on assets (ROA) between the previous and the current year.

We define three main independent variables related to the presence of institutional investors in the board of directors. To begin, we define INSTIT as the proportion of directors appointed by institutional investors. We then make the distinction between pressure-sensitive and pressure-resistant directors. Thus, we define SENSIT as the proportion of board members who represent pressure-sensitive institutional investors (i.e., banks and insurance companies) and RESIST as the proportion of the board members who represent pressure-resistant institutional investors (primarily mutual funds and pension funds). We also interact INSTIT, SENSIT, and RESIST with the previous year's ROA to compute INSTITROA, SENSITROA, and RESISTROA, respectively. These three variables introduce the moderating effect of the board composition conditional on the performance of the firm.

We control for a number of factors that can potentially affect retributions and that make our research comparable to previous studies (Almazán et al., 2005; David et al., 1998; Doucouliagos et al., 2007; Fernández Méndez et al., 2012; Sánchez Marín et al., 2013). SIZE is the log of total assets and is a measure of firm size. LEV is the financial leverage variable, measured as the ratio of book value of debt to total assets. MTB is the equity market-to-book value, which proxies both growth opportunities and market expectations about the firm. We also control for ROA. Appendix provides a summary of all the variables.

Empirical methodWe first report a descriptive analysis to show the main characteristics of our sample. This step provides preliminary evidence about the possible effect of institutional directors on the compensation of the directors and about possible differences between the types of institutional directors. Next, we perform an explanatory analysis to test our hypotheses. We run the following baseline model:

where COMPENSAT represents the variables of directors compensation as previously defined; BOARDit represents the variables of institutional directorships; BOARDROAit represents the interaction between ROA and the variables of institutional directorships; ηi represents the individual effect; ηi represents the time effect; and ¿it represents the stochastic error. The time effect includes the macroeconomic factors that affect all the firms in the same period.Our database combines time-series with cross-sectional data, allowing for the formation of panel data, which we estimate with the appropriate panel data methodology (Arellano, 2003). In the estimation of our model, two problems can arise: constant and unobservable heterogeneity and endogeneity. Constant and unobservable heterogeneity refers to specific characteristics of each firm that remain constant over time as represented by the fixed-effects term ηi. Because they are unobservable, they become part of the random component in the estimated model. Panel data methodology enhances the control of this constant and unobservable heterogeneity introduced by the fixed-effects term.

The endogeneity problem may appear because lagged directors’ compensation can affect the structure of the board of directors (Demsetz and Villalonga, 2001; Hermalin and Weisbach, 1998; Villalonga and Amit, 2006). To address this problem, Blundell and Bond (1998) and Bond (2002) suggest the use of the panel data system estimator. This procedure is an improved version of the generalized method of moments, given the possibility that weak instruments can induce poor asymptotic precision (Alonso-Borrego and Arellano, 1999). This method provides efficient estimates whose consistency depends critically on the absence of second-order serial autocorrelation in the residuals and on the validity of the instruments (Arellano and Bond, 1991). Accordingly, we report the m2 test. To test the validity of the instruments, we use the Hansen test of overidentifying restrictions, which allows us to test the absence of a correlation between the instruments and the error term and, therefore, to check the validity of the selected instruments.

As an alternative way to address the endogeneity issues and to check the consistency of our results, we also estimate our model using the instrumental variables method. More specifically, we implement the two-stages least squares method to instrument the corporate governance variables.

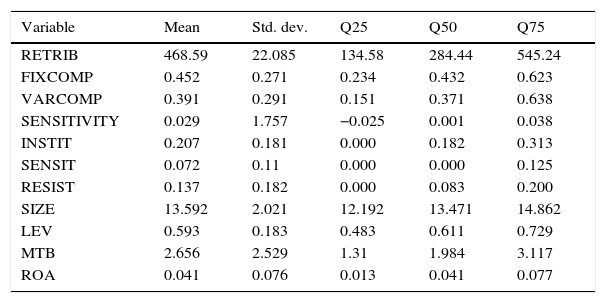

ResultsDescriptive statisticsTable 1 presents the mean value, the standard error, and the quartiles of the main variables. The representatives of institutional investors account for around 21% of directorships, with pressure-resistant directors twice as important as pressure-sensitive directors. Consistent with the international trend to increase the importance of institutional investors (Li et al., 2006), the proportion of directors appointed by institutional investors in our sample increases from 19.6% in 2004 to 21.7% in 2010.

Main descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Mean | Std. dev. | Q25 | Q50 | Q75 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RETRIB | 468.59 | 22.085 | 134.58 | 284.44 | 545.24 |

| FIXCOMP | 0.452 | 0.271 | 0.234 | 0.432 | 0.623 |

| VARCOMP | 0.391 | 0.291 | 0.151 | 0.371 | 0.638 |

| SENSITIVITY | 0.029 | 1.757 | −0.025 | 0.001 | 0.038 |

| INSTIT | 0.207 | 0.181 | 0.000 | 0.182 | 0.313 |

| SENSIT | 0.072 | 0.11 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.125 |

| RESIST | 0.137 | 0.182 | 0.000 | 0.083 | 0.200 |

| SIZE | 13.592 | 2.021 | 12.192 | 13.471 | 14.862 |

| LEV | 0.593 | 0.183 | 0.483 | 0.611 | 0.729 |

| MTB | 2.656 | 2.529 | 1.31 | 1.984 | 3.117 |

| ROA | 0.041 | 0.076 | 0.013 | 0.041 | 0.077 |

This table provides the mean, standard deviation, and quartiles of the main variables. See Appendix for variable definitions.

Table 2 reports the correlation matrix among the variables. With the exception of some relations among the variables of corporate governance, all of them present low correlation coefficients, so that multicollinearity should not be a concern. In addition, the possibility of multicollinearity can be ruled out on the basis of two facts. First, our model is a parsimonious one, so the variables of corporate governance (INSTIT, SENSIT, and RESIST) are not simultaneously included in the model. Second, we also provide a variance inflation factor (VIF). Our VIF scores are below 3, and thus we confirm that multicollinearity does not skew our results (Belsley et al., 2004; Kutner et al., 2005).

Correlation matrix.

| RETRIB | FIXCOMP | VARCOMP | SENSITIVITY | INSTIT | SENSIT | RESIST | SIZE | LEV | MTB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIXCOMP | −0.248 | |||||||||

| VARCOMP | 0.228 | −0.739 | ||||||||

| SENSITIVITY | −0.106 | −0.013 | −0.013 | |||||||

| INSTIT | −0.058 | 0.126 | −0.114 | −0.063 | ||||||

| SENSIT | 0.036 | 0.135 | −0.184 | −0.066 | 0.394 | |||||

| RESIST | −0.081 | 0.048 | −0.004 | −0.025 | 0.811 | −0.218 | ||||

| SIZE | 0.554 | −0.160 | 0.187 | −0.052 | 0.060 | 0.229 | −0.082 | |||

| LEV | 0.178 | −0.048 | 0.009 | −0.073 | 0.171 | 0.068 | 0.138 | 0.434 | ||

| MTB | 0.050 | −0.054 | 0.077 | −0.030 | −0.094 | −0.069 | −0.055 | 0.095 | 0.082 | |

| ROA | 0.158 | −0.055 | 0.200 | −0.054 | −0.180 | −0.077 | −0.142 | 0.132 | −0.335 | 0.353 |

| VIF | 1.560 | 1.470 | 1.430 | 1.360 | 1.260 | 1.130 |

This table presents the Pearson's correlation matrix. See Appendix for variable definitions.

For an exploratory analysis, we divide the sample into two groups depending on the proportion of institutional investors (pressure-sensitive investors and pressure-resistant investors) in the boardroom: the group of firms with the proportion of institutional directors over the INSTIT median value and the group of firms with the proportion of institutional directors under the INSTIT median value. The same pattern applies to SENSIT and RESIST variables. Then, we conduct a test of means comparison to explore whether compensation schemes are different between both groups. Table 3 reports the results. Although not conclusive, the findings suggest that gray directors appointed by institutional investors are related to differences in directors’ compensation. Whereas the proportion of institutional directors does not seem to induce significant differences, pressure-sensitive directors have asymmetric effects, compared to pressure-resistant directors. More specifically, directors representing pressure-resistant institutional investors are positively related to the variable component and negatively related to the fixed part of the compensation. Conversely, pressure-sensitive directors are related to a higher fixed part and to a lower variable component of directors’ compensation.

Test of means comparison.

| RETRIB | FIXCOMP | VARCOMP | SENSITIVITY | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High level | Low level | p-Value | High level | Low level | p-Value | High level | Low level | p-Value | High level | Low level | p-Value | |

| INSTIT | 498.02 | 439.83 | 0.97 | 0.443 | 0.461 | 0.49 | 0.410 | 0.373 | 0.19 | 0.132 | 0.065 | 0.27 |

| SENSIT | 381.50 | 563.08 | 0.00 | 0.481 | 0.433 | 0.06 | 0.320 | 0.438 | 0.00 | 0.087 | 0.057 | 0.43 |

| RESIST | 429.71 | 493.17 | 0.39 | 0. 429 | 0. 474 | 0.08 | 0.415 | 0. 368 | 0.09 | 0.104 | 0.038 | 0.43 |

This table provides the median value of board fixed compensation (RETRIB), fixed component (FIXCOMP), variable component of total compensation (VARCOMP) and sensitivity conditional on the high or low level of institutional directors (INSTIT), pressure-sensitive (SENSIT) and pressure-resistant directors (RESIST). p-Value is the significance level to accept the null hypothesis of equality of means between groups.

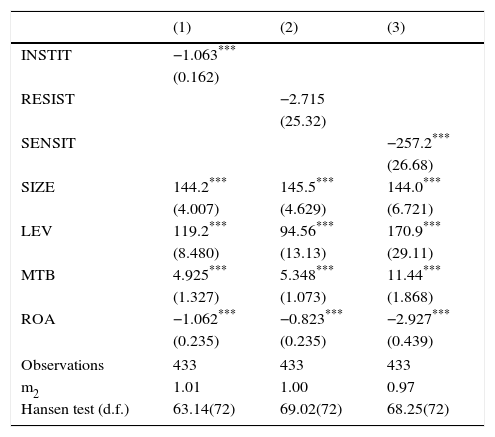

Table 4 provides the estimates related to total compensation. We test the effects of all institutional directors, pressure-sensitive institutional directors, and pressure-resistant institutional directors on the average compensation of directors (RETRIB). Column (1) shows that all institutional directors (INSTIT) have a direct negative relation on RETRIB. This result is in line with some other studies that focus on Anglo-Saxon countries in which institutional ownership make some appreciable differences in the level of policy pay (Cosh and Hughes, 2007).

Generalized method of moments estimates of the baseline model (total compensation).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| INSTIT | −1.063*** | ||

| (0.162) | |||

| RESIST | −2.715 | ||

| (25.32) | |||

| SENSIT | −257.2*** | ||

| (26.68) | |||

| SIZE | 144.2*** | 145.5*** | 144.0*** |

| (4.007) | (4.629) | (6.721) | |

| LEV | 119.2*** | 94.56*** | 170.9*** |

| (8.480) | (13.13) | (29.11) | |

| MTB | 4.925*** | 5.348*** | 11.44*** |

| (1.327) | (1.073) | (1.868) | |

| ROA | −1.062*** | −0.823*** | −2.927*** |

| (0.235) | (0.235) | (0.439) | |

| Observations | 433 | 433 | 433 |

| m2 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.97 |

| Hansen test (d.f.) | 63.14(72) | 69.02(72) | 68.25(72) |

This table provides the estimated coefficients (t-stats) through the generalized method of moments. The dependent variable is RETRIB. See Appendix for variable definitions. m2 is a test of second order serial autocorrelation. Hansen test is a test of overidentifying restrictions, which distributes as χ2 (degrees of freedom).

More interesting, columns (2) and (3) show that RESIST does not have a significant impact on the total compensation of each director, whereas SENSIT has a significant negative effect. These results do suggest that the only type of institutional directors effectively affecting the whole board compensation is the pressure-sensitive one. These results can be understood at the light of the different incentives that pressure-resistant and pressure-sensitive directors face. Since pressure-resistant ones are supposed to provide a more independent managerial oversight, the higher compensation of boards with pressure-resistant directors can be due to the compensation package working as an incentive for better corporate performance when directors are interested in providing such oversight.

Consistent with Almazán et al. (2005), Khan et al. (2005) and Shin and Seo (2011), the estimates of our control variables show that directors of the larger firms (SIZE) receive higher fixed compensation. Directors of larger companies are expected to be paid more than directors of small firms due to the higher degree of complexity of tasks, the potentially greater value placed on directors’ decisions, and, hence, the greater reward from making them (Doucouliagos et al., 2007). In the same vein, directors of more leveraged firms and firms with more growth opportunities have a higher compensation.

We now test hypothesis H1 and the way in which ROA affects directors’ compensation depending on the type of institutional investors (Table 5). In Column 1 we report the broad effect of institutional directorship: while, consistent with Table 4, INSTIT have a negative effect on directors compensation, the interaction with ROA has a positive and significant effect. It means that, although the representation of institutional investors in the board of directors can reduce the average total compensation, it also ties it to the performance of the firm or the board. Furthermore, when splitting this effect into the influence of both kinds of institutional investors, we find asymmetric effects. On the one hand, the positive coefficient of RESIST·ROA implies that pressure resistant directors tie the board compensation to the performance of the board. On the other hand, the non-significant coefficient of SENSIT·ROA suggests a less disciplinary role for this kind of investors since the compensation and incentives of the board are not so closely tied to its performance. The results of this empirical analysis are consistent with the implications of our model that pressure-resistant directors can provide more intense monitoring of corporate management.

Generalized method of moments estimates of the baseline model (total compensation).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| INSTIT | −1.316*** | ||

| (0.147) | |||

| INSTIT·ROA | 0.201*** | ||

| (0.0133) | |||

| RESIST | 13.96 | ||

| (26.82) | |||

| RESIST·ROA | 4.019** | ||

| (1.592) | |||

| SENSIT | −267.8*** | ||

| (57.69) | |||

| SENSIT·ROA | −0.0443 | ||

| (5.115) | |||

| SIZE | 150.2*** | 146.8*** | 149.3*** |

| (5.347) | (5.099) | (7.582) | |

| LEV | 219.2*** | 119.3*** | 167.0*** |

| (16.93) | (20.20) | (34.90) | |

| MTB | 2.990*** | 4.598*** | 10.89*** |

| (0.863) | (1.137) | (1.954) | |

| ROA | −2.777*** | −1.205*** | −3.011*** |

| (0.362) | (0.358) | (0.448) | |

| Observations | 433 | 433 | 433 |

| m2 | 1.01 | 0.97 | 0.94 |

| Hansen test (d.f.) | 67.67(72) | 66.39(72) | 63.55(72) |

This table provides the estimated coefficients (t-stats) through the generalized method of moments. The dependent variable is RETRIB. See Appendix for variable definitions. m2 is a test of second order serial autocorrelation. Hansen test is a test of overidentifying restrictions, which distributes as χ2 (degrees of freedom).

We now address the question about whether the composition of the compensation package depends on the type of directors representing institutional investors (H2). Table 6 reports the results of the estimations in which FIXCOMP (the fixed proportion) is the dependent variable. Column (1) shows that the broad effect of all institutional directors (INSTIT) is a lower base salary.

Generalized method of moments estimates of the baseline model (proportion of fixed compensation).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| INSTIT | −0.132*** | ||

| (0.0245) | |||

| RESIST | −19.04*** | ||

| (3.456) | |||

| SENSIT | 22.96*** | ||

| (4.342) | |||

| SIZE | −5.152*** | −5.283*** | −5.441*** |

| (0.406) | (0.419) | (0.393) | |

| LEV | 32.93*** | 33.08*** | 17.17*** |

| (2.053) | (2.197) | (3.994) | |

| MTB | −3.237*** | −3.220*** | −2.214*** |

| (0.142) | (0.143) | (0.214) | |

| ROA | 0.258*** | 0.350*** | 0.214*** |

| (0.0756) | (0.0615) | (0.0536) | |

| Observations | 434 | 434 | 434 |

| m2 | −0.32 | −0.27 | 0.22 |

| Hansen test | 70.88(72) | 69.97(72) | 69.42(72) |

This table provides the estimated coefficients (t-stats) through the generalized method of moments. The dependent variable is FIXCOMP. See Appendix for variable definitions. m2 is a test of second order serial autocorrelation. Hansen test is a test of overidentifying restrictions, which distributes as χ2 (degrees of freedom).

Table 6 shows the results for the different types of institutional directors and different patterns for proportion of fixed compensation. The negative coefficient of RESIST in Column (2) suggests that pressure-resistant directors tend to reduce the fixed proportion of the salary. Conversely, Column (3) shows that directors representing pressure-sensitive institutional investors increase the fixed component of the compensation, which confirms H2. According to these results, the directors appointed by institutional investors have a completely different effect on the fixed component of the compensation conditional on the nature of the institutional investor. This result can be understood in terms of the ability to monitor of each group of institutional investors. Since pressure resistant investors have lower implied costs of monitoring, our results are consistent with Almazán et al. (2005), who find that directors representing active institutional investors (pressure-resistant directors) face lower costs of monitoring than the directors appointed by passive institutions (pressure-sensitive directors).

Table 7 reports consistent results when we estimate the determinants of the variable component of directors’ compensation (VARCOMP). Column (1) shows that directors representing institutional investors increase the variable component. Nevertheless, the influence of institutional directors on the variable component of the compensation is not homogeneous. Coherent with a more disciplinary role, RESIST exhibits a positive impact, so that pressure-resistant directors increase the relative weight of the variable compensation. On the contrary, consistent with the view that pressure-sensitive investors are more transient, the proportion of these directors (SENSIT) has a negative influence. Due to the lower conflicts of interests and their interest in aligning board interests with shareholder interests, we confirm that directors appointed by pressure-resistant institutional investors will prefer long-term incentive plans than directors appointed by pressure-sensitive institutional investors.

Generalized method of moments estimates of the baseline model (variable proportion of board compensation).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| INSTIT | 0.141*** | ||

| (0.0386) | |||

| RESIST | 17.79*** | ||

| (2.337) | |||

| SENSIT | −45.94*** | ||

| (7.607) | |||

| SIZE | 3.949*** | 3.669*** | 4.189*** |

| (0.391) | (0.296) | (0.391) | |

| LEV | −13.44*** | −12.72*** | −9.101** |

| (2.774) | (2.547) | (3.486) | |

| MTB | 0.632*** | 0.495*** | 0.330* |

| (0.140) | (0.146) | (0.170) | |

| ROA | 0.179*** | 0.178*** | 0.0279 |

| (0.0454) | (0.0502) | (0.0312) | |

| Observations | 414 | 414 | 414 |

| m2 | −1.61 | −1.18 | −1.25 |

| Hansen test (d.f) | 62.53(72) | 57.10(72) | 60.32(72) |

This table provides the estimated coefficients (t-stats) through the generalized method of moments. The dependent variable is VARCOMP. See Appendix for definition of variables. m2 is a test of second order serial autocorrelation. Hansen test is a test of overidentifying restrictions, which distributes as χ2 (degrees of freedom).

These results are in line with David et al. (1998) and Almazán et al. (2005), who find that pressure-resistant institutional investors are more likely than pressure-sensitive institutional investors to align pay policy to shareholder preferences.

In any case, the variable remuneration can have some effects on risk. The European Commission has found that the incentives created by variable pay schemes may have resulted in excessive risk taking and in ever-increasing levels of remuneration (EUCGF, 2009). From this point of view, our results may shed some light on the relation between institutional investors and corporate risk taking (Crespí and Pascual, 2012; Shin and Seo, 2011).

A comparison of Tables 6 and 7 provides interesting insights regarding the control variables. SIZE and MTB have a negative influence on the fixed component and a positive influence on the variable component. These findings mean that larger companies and firms with more growth opportunities tend to rely more on the variable component than on the base salary. Conversely, financial leverage shows the opposite effect: it has a positive effect on fixed compensation and a negative effect on variable compensation.

Finally, Table 8 provides the results related to H3, concerning the sensitivity of compensation to performance. Column (1) shows that institutional directors have a positive influence on pay-performance sensitivity. Nevertheless, significant differences exist between both types of institutional investors, as shown in columns (2) and (3). The coefficient of RESIST is positive in comparison to the negative coefficient of SENSIT, which suggests that the directors representing pressure-resistant investors induce compensation packages sensitive to performance whereas pressure-sensitive directors do not. Again, this result is consistent with the view that the different types of directors take on different roles and that pressure-resistant directors undertake a more thorough monitoring role. In line with John et al. (2010) and John and Qian (2003), the pay-for-performance sensitivity of board compensation decreases with the leverage ratio and increases with firm size at the 1% level.

Generalized method of moments estimates of the baseline model (sensitivity of compensation to performance).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| INSTIT | 0.00849*** | ||

| (0.00284) | |||

| RESIST | 1.095* | ||

| (0.649) | |||

| SENSIT | −1.338*** | ||

| (0.336) | |||

| SIZE | 1.402*** | −0.163 | −0.200 |

| (0.0636) | (0.146) | (0.136) | |

| LEV | −3.167*** | −3.820*** | −4.417*** |

| (0.242) | (0.384) | (0.437) | |

| MTB | 0.0141*** | −0.0353*** | −0.0314*** |

| (0.00347) | (0.00353) | (0.00378) | |

| ROA | −0.00241** | 0.0270*** | 0.0255*** |

| (0.00120) | (0.00433) | (0.00433) | |

| Observations | 401 | 401 | 401 |

| m2 | 1.02 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Hansen test | 73.49(66) | 70.69(66) | 73.43(66) |

This table provides the estimated coefficients (t-stats) through the generalized method of moments. The dependent variable is SENSITIVITY. See Appendix for definition of variables. m2 is a test of second order serial autocorrelation. Hansen test is a test of overidentifying restrictions, which distributes as χ2 (degrees of freedom).

As previously noted, we present some further analysis to check the sensitivity of our results to different estimation methods to address the endogeneity problem. We run new estimates using the two-stages least squares method. Table 9 reports the estimates for the models in which total compensation (RETRIB) is the dependent variable: in Columns (1)–(3) we explore the effect of institutional directors on the board compensation and in Columns (4)–(6) we test our first hypothesis about the differential moderating effect of each kind of directors. Table 10 reports the estimates for the models in which the fixed component of the compensation (FIXCOMP) – Columns (1)–(3) – the variable component (VARCOMP) – Columns (4)–(6) – and the pay-for-performance sensitivity – Columns (7)–(9) – are the dependent variables. Both tables corroborate the results previously reported.

Two-stage least squares estimates of the baseline models.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (6) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INSTIT | −0.921** | −4.812*** | ||||

| (0.442) | (1.243) | |||||

| INSTIT·ROA | 0.195** | |||||

| (0.0868) | ||||||

| RESIST | 16.94 | −100.4*** | ||||

| (48.59) | (36.18) | |||||

| RESIST·ROA | 58.99*** | |||||

| (22.39) | ||||||

| SENSIT | −328.2*** | −301.9*** | ||||

| (76.46) | (80.57) | |||||

| SENSIT·ROA | −12.57 | |||||

| (12.29) | ||||||

| SIZE | 88.20*** | 87.54*** | 91.56*** | 90.49*** | 82.33*** | 91.88*** |

| (5.086) | (5.103) | (5.084) | (5.499) | (7.133) | (5.088) | |

| LEV | −50.78 | −75.04 | −65.61 | 42.91 | 125.1 | −72.76 |

| (52.52) | (52.79) | (50.78) | (62.94) | (99.35) | (51.20) | |

| MTB | 2.143 | 2.725 | 2.205 | 0.753 | −0.821 | 1.872 |

| (1.986) | (1.991) | (1.943) | (2.174) | (2.959) | (1.967) | |

| ROA | 0.112 | 0.182 | −0.156 | −2.116 | −3.910* | 0.131 |

| (0.977) | (0.981) | (0.964) | (1.398) | (2.056) | (1.003) | |

| Observations | 433 | 433 | 433 | 433 | 433 | 433 |

| R-squared | 0.508 | 0.503 | 0.524 | 0.434 | 0.367 | 0.525 |

This table provides the estimated coefficients (t-stats) through the two least squares model. The dependent variable is RETRIB. See Appendix for variable definitions.

Two-stage least squares estimates.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIXCOMP | FIXCOMP | FIXCOMP | VARCOMP | VARCOMP | VARCOMP | SENSITIVITY | SENSITIVITY | SENSITIVITY | |

| INSTIT | 0.536*** | −0.205 | 0.0101 | ||||||

| (0.175) | (0.128) | (0.0219) | |||||||

| RESIST | −63.04** | 43.61** | −0.586 | ||||||

| (24.59) | (18.00) | (0.436) | |||||||

| SENSIT | 40.32*** | −56.61*** | −2.220* | ||||||

| (12.87) | (9.719) | (1.330) | |||||||

| SIZE | −3.508*** | −3.327*** | −3.401*** | 1.777*** | 1.194* | 1.212* | 0.00954 | 0.00380 | −0.00368 |

| (0.862) | (0.941) | (0.876) | (0.636) | (0.699) | (0.646) | (0.0377) | (0.0418) | (0.0477) | |

| LEV | 11.49 | 25.21** | 0.175 | 4.397 | −3.808 | 8.885 | −0.489 | −0.987* | −1.303* |

| (8.594) | (10.74) | (9.622) | (6.325) | (7.944) | (6.897) | (0.354) | (0.452) | (0.637) | |

| MTB | −0.759** | −1.079*** | −0.514 | −0.0304 | 0.190 | −0.0755 | −0.00981 | −0.00899 | −0.000906 |

| (0.327) | (0.375) | (0.348) | (0.237) | (0.273) | (0.249) | (0.0127) | (0.0161) | (0.0203) | |

| ROA | 0.00792 | −0.0193 | 0.00901 | 0.188 | 0.274* | 0.233* | −0.00271 | −0.0166* | −0.0152 |

| (0.163) | (0.179) | (0.166) | (0.129) | (0.143) | (0.132) | (0.00625) | (0.00764) | (0.00824) | |

| Observations | 428 | 428 | 428 | 428 | 428 | 428 | 416 | 416 | 416 |

| R-squared | 0.116 | 0.195 | 0.075 | 0.142 | 0.181 | 0.107 | 0.234 | 0.163 | 0.118 |

This table provides the estimated coefficients (t-stats) through the two least squares model. The dependent variables are FIXCOMP, VARCOMP and SENSITIVITY. See Appendix for variable definitions.

Director remuneration has been the focus of considerable attention from the public, media, academia, and the policymakers in recent years. The debate can be approached from various angles: as optimal pay structure for aligning pay with performance to reduce agency costs; as a regulatory issue with the objective of remedying any system flaws; and as a public policy concern.

Although prior research has provided significant insights on the relation between institutional investors and managerial compensation, little is still know about the board members compensation. It is a relevant topic since, unlike managers, directors are supposed to set their own compensation, which gives rise to new incentives and conflicts of interests. Thus, the contributions of our research are twofold: first, we study the effect of institutional investors on directors’ compensation rather than managerial compensation. Second, we focus on the effect of institutional investors as directors rather than owners. Both issues have not been addressed by previous research.

We analyze the role of institutional directors in compensation policies of Spanish listed firms during the period 2004–2010. Heidrick and Struggles (2011) find that Spain is the European country with the highest proportion of directors representing institutional investors. Thus, the Spanish case provides new insights to the international governance literature (Baixauli-Soler and Sánchez-Marín, 2011; Firth et al., 2007) and allows capturing the relation between institutional investors and compensation policies better than in a US or UK setting, where directors appointed by institutional investors are less common.

Our research corroborates the view that institutional investors are far from being a monolithic group and underline the differences among different types of directors regarding objectives, stability, scrutiny, and visibility. We make a distinction between those directors appointed by institutional investors who maintain business relations with the firm on whose board they sit (pressure-sensitive directors) and those appointed by institutional investors whose business activity is not related to the company in which they hold a directorship (pressure-resistant directors). We study the impact of institutional directors on two aspects of remuneration policy: composition and sensitivity. We also check whether institutional directors have a significant moderating effect on the relation between performance and board remuneration. Specifically, we find that only the directors appointed by pressure-resistant institutional investors, compared to pressure-sensitive institutional investors, effectively reduce the fixed component of board remuneration and increase the pay-for-performance sensitivity. Conversely, the pressure-sensitive directors decrease the total board compensation and the variable component of the compensation package.

Taken together, these results suggest that directors appointed by pressure-resistant investors serve a superior monitoring role in mitigating the agency problems inside the firm by enhancing the role of the compensation as a mechanism of corporate governance and making the board compensation more tied to the firm's performance. These results confirm that institutional investors’ fiduciary responsibilities, conflicts of interest, and information asymmetry interact with each other to determine jointly the influence of institutional investors on remuneration. Other theoretical arguments to support our results can be found in the different attitude toward risk between different types of directors.

Our research has interesting academic and policy implications for the debate over the proper degree of institutional involvement in corporate governance. When analysing the role of institutional investors, researchers must take into account investors’ participation in other mechanisms of corporate control such as the board of directors and their different agendas and incentives for corporate governance. In particular, directors appointed by institutional investors should not be considered as a homogenous group, especially in a context in which the main agency conflict stems from a divergence of interests between dominant and minority shareholders and where the role of institutional directors is highly relevant. These findings have important public policy implications and suggest that regulatory organizations could revisit their policies on large equity positions of directors appointed by institutional investors and the ability of groups of institutional investors to have more to say in compensation governance practices.

Our paper has some limitations that could be addressed in future research. First, the interaction between both ways of institutional investors influence (ownership and directorships) could be introduced jointly. It could enhance testing whether there are substitute or complementary effects between them. Another avenue for research is analyzing the presence of institutional directors in the compensation committee rather than in the whole board of directors. Third, once a longer time period was available, the attention could be paid to the effect of the financial crisis and the extent to which the allegedly new compensation design is a right answer to the new financial scenario.

| Variables | Description |

|---|---|

| RETRIB | Total compensation of the board divided by the number of directors |

| FIXCOMP | Fixed component of the total compensation of the board |

| VARCOMP | Variable component of the total compensation of the board |

| SENSITIVITY | Variation in the compensation of the board relative to the variation of return on assets (ROA) between the previous and the current year. |

| INSTIT | Proportion of directors who represent institutional investors |

| SENSIT | Proportion of the directors who represent pressure-sensitive institutional investors |

| RESIST | Proportion of the directors who represent pressure-resistant institutional investors |

| SENSITROA | Interaction of SENSIT and ROA variables |

| RESISTROA | Interaction of RESIST and ROA variables |

| INSTITROA | Interaction of INSTIT and ROA variables |

| LEV | Ratio of book debt to total assets |

| MTB | Equity market to book ratio |

| SIZE | Total assets (log) |

| ROA | Gross profit to total assets |

The authors are grateful to Alisa Larson, Mónica López-Puertas Lamy, Kurt Desender, Xosé H. Vázquez (associate editor) and two anonymous referees for their comments on previous versions of the paper, and for the financial support provided by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (ECO2011-29144-C03-01 and ECO2011-29144-C03-02). All the remaining errors are the authors’ sole responsibility.

Amadeus is a product of Bureau van Dijk Electronic Publishing and provides comparable standardized financial information for companies across Europe.

Although FIXCOMP and VARCOMP may be in opposition, these variables are not the only components to consider. Total retribution may also include meetings attendance fees, stocks, options, and other ways of compensation.