Partnerships between businesses and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have become widely adopted mechanisms for collaboration in addressing complex social issues, the aim being to take advantage of the two types of organizational rationale to generate mutual value. Many such alliances have proved to be unsuccessful, however. To assist managers improve the likelihood of success of their collaborative relationships, the authors propose a success model of business-NGO partnering processes based on Relationship Marketing Theory. They also analyse the theoretical bases of the model's hypotheses through a meta-analytical study of the existing literature.

Partnerships between businesses and nonprofit organizations (NPOs) have grown substantially in the last two decades (Bennett et al., 2008; Murphy et al., 2014). One reason is their enormous potential in addressing complex social problems, while, in turn, providing multiple benefits for the partners (Berger et al., 2006; Bennett et al., 2008; Reed and Reed, 2009; Austin and Seitanidi, 2012a,b; Stadtler, 2012; Sakarya et al., 2012; Schiller and Almog-Bar, 2013; Al-Tabbaa et al., 2014; Murphy et al., 2014). Indeed, a study by the PrC/Partnerships Resource Centre (2011) finds the world's largest firms to have, on average, 18 ongoing cross-sector collaborations, most of them with NPOs. Their objectives are to contribute to solving social problems, to strengthen their position as market leaders, or, from sharing knowledge and know-how, to develop better products.

However, despite their importance, a large proportion of these partnership processes are unsuccessful (Galaskiewicz and Colman, 2006; Gutiérrez et al., 2012). This is due mainly to the many problems involved in their management (Kolk et al., 2010), such as mistrust, misunderstandings, or power imbalances between the partners (Berger et al., 2004; Selsky and Parker, 2005; Seitanidi and Ryan, 2007). In this sense, various researchers have consequently focused their analyses on the factors favouring the success of these processes during the different stages of their development, especially during their formation and initial implementation (Jamali and Keshishian, 2009; Le Ber and Branzei, 2010; Jamali et al., 2011; Seitanidi et al., 2010; Austin and Seitanidi, 2012b; McDonald and Young, 2012). However, to date, the number of explanatory theoretical frameworks for success in partnerships, constructed from different perspectives, has been very limited (with exceptions such as Seitanidi and Crane, 2009; Clarke and Fuller, 2010; Seitanidi, 2010; Murphy and Arenas, 2010; Le Ber and Branzei, 2010; Venn, 2012; Sanzo et al., 2014; Murphy et al., 2014). This scarcity in the literature is even more evident on those success models developed under one Relationship Marketing approach (Sanzo et al., 2014), theoretical perspective which is considered well-suited to this purpose since it has been widely used in the design of models of success in strategic contexts (Hunt et al., 2002; Arenas and García, 2006; Wittmann et al., 2009).

Since its inception, research in Relationship Marketing has worked on identifying and weighing the key constructs determining success in different partnership processes. However, a narrative review of the links between these constructs has showed a diversity of results (Palmatier et al., 2006), which has markedly limited the generalizability of the obtained conclusions (Camisón et al., 2002). There is thus a need to conduct meta-analyses which, by synthesizing the results of previous studies, can improve the scientific knowledge generated up to that time (Geyskens et al., 2009). There have as yet, however, been very few meta-analytical studies in the field of Relationship Marketing. Among the existing studies, it should be highlighted the work conducted by Palmatier et al. (2006), because of the amplitude of its scope, including a large number of links between different constructs. However, this study focuses on the specific “customer-seller” context, with no reference therefore to the research context of the present work, i.e., “business-NGO” relationships.

In this sense, the specific objectives of the present study were twofold: first, to cover the gap we had identified in research by proposing a model of success for partnership processes between firms and NGOs based on Relationship Marketing Theory, and second, given the divergence of results in the literature, to conduct a meta-analytical study of the theoretical support for the model's hypotheses, which could then serve as a basis for future research. The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section ‘A relational approach to business-NGO partnerships’ analyses alliances between firms and NGOs from a relational perspective, and, following a review of the literature in the domain of Relationship Marketing, presents a success model for such partnership processes. Section ‘Meta-analytic study of the proposed model’ describes the basic notions of meta-analytical techniques, and presents the main results of their use in this study. Finally, section ‘Conclusions and implications for management’ presents the main conclusions of the study, and discusses their implications for management, the limitations of the study, and indications for future research.

A relational approach to business-NGO partnershipsConcept and evolution of Relationship MarketingBecause of its importance and differentiating features, the Relationship Marketing paradigm has received much attention in recent decades on the part of both academics and professionals.

The term “relationship marketing” first appeared in 1983 in a book chapter published by Berry (Berry, 1995). In this chapter, Berry (1983, p. 25) defined it as “attracting, maintaining, and enhancing customer relationships”. Since then, numerous authors have proposed many alternative definitions of the term, being most of them collected in different research works. Among the existing studies, it should be highlighted the exhaustive work of Harker (1999), which identified 26 different definitions of the concept published up to that time. The conclusion of his study was that the most widely accepted definition of Relationship Marketing in the literature was that of Grönroos (1994): “Relationship marketing is to identify and establish, maintain and enhance and when necessary also to terminate relationships with customers and other stakeholders, at a profit, so that the objectives of all parties are met, and that this is done by a mutual exchange and fulfilment of promises”. Also, in order to update and improve the work of Harker (1999), Agariya and Singh (2011) identified 72 definitions of Relationship Marketing in the literature, covering a 28-year period (1982–2010). According to those authors, although the definitions identified in the literature differ slightly due to different contextual scenarios in which they had been put forward, the core of all of them revolved around the acquisition, the retention, the improvement of profitability, the long-term orientation, and the presence of a win-win situation for all of a firm's stakeholders.

Thus, as can be gleaned from the various definitions of relationship marketing mentioned previously, numerous researchers have observed that the scope of relationship marketing should not be restricted to the maintenance of relationships between the firm and its customers but should also include the firm's relationships with various other stakeholders. This extension to other actors is consistent with and strongly linked to the strategic approach of Stakeholder Marketing (Bhattacharya and Korschun, 2008; Bhattacharya, 2010; Smith et al., 2010; Mish and Scammon, 2010), which “looks beyond customers as the target of marketing activities and firms as the primary intended beneficiary” (Bhattacharya and Korschun, 2008, p. 113). In consequence, firms needs to design, implement, and evaluate its marketing strategy taking all of its stakeholders into account (Bhattacharya, 2010). Relationship Marketing is no stranger to this idea. In fact, it can be found in the literature on this field several contributions recognizing its various target stakeholder groups (Frow and Payne, 2011; see Table 1), with NGOs being one of them (Morgan and Hunt, 1994).

Different approaches to describing stakeholders in Relationship Marketing.

| Author | Categories |

|---|---|

| Christopher et al. (1991) | 6 markets: a consumer market and five secondary markets. |

| Kotler (1992) | 10 actors: four actors of the immediate environment and six of the macro-environment. |

| Morgan and Hunt (1994) | 10 relationships, corresponding to four types of partnership: • Supplier partnerships: Partnerships involving relational exchanges between manufacturers and suppliers of goods or services. • Buyer partnerships: Long-term exchanges between businesses and end customers, or relational exchanges of working partnerships. • Internal partnerships: Exchanges established with functional departments between a firm and its employees, or within the firm itself with its business units. • Lateral partnerships: Strategic alliances between businesses and their competitors, businesses and NGOs, or businesses and national, state, or local governments. |

| Gummesson (1997) | 30 relationships: seventeen market relationships (three classic and fourteen special) and thirteen non-market relationships (six mega-relationships and seven nano-relationships). |

| Doyle (1995) | 4 types of network: partnerships with suppliers, partnerships with customers, internal partnerships, and external partnerships. |

| Laczniak (2006) | 6 different groups of stakeholders, divided into primary and secondary. |

Relationship Marketing Theory, unlike other approaches, stresses that success in the relational exchanges between different agents results from certain characteristics being present in the relationship. In particular, following the arguments of various authors (Hunt et al., 2002; Wittmann et al., 2009), partnerships between businesses and NGOs which exhibit different key characteristics in such exchanges to a greater intensity will be more successful than those which do not. In order therefore to determine which attributes are fundamental in exchanges between firms and NGOs, this study has carried out a review of the main theoretical models proposed for this particular type of relationship.

This analysis of the literature, although exhaustive, has uncovered only three research studies on this type of exchange: MacMillan et al. (2005); Reinhard (2012); and Sanzo et al. (2014). The key variables they have mentioned are listed in Table 2.

Key variables mentioned in the Relationship Marketing literature on exchanges between businesses and NGOs.

| Authors | Antecedents | Mediation | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| MacMillan et al. (2005) | Termination costs Communication Material benefits Shared Values Opportunistic behaviour | Commitment Trust | |

| Reinhard (2012) | Termination costs Communication Material benefits Shared values Opportunistic behaviour | Commitment Trust | |

| Sanzo et al. (2014) | Shared values Conflict Reputation damage risk Perceived benefits Communication Trust Commitment | Learning | Internal marketing Funding Technology Scale of operations Visibility Mission accomplishment |

Given this limited number of works on the specific research context of the present study, it was considered appropriate to also review the literature on relational models between businesses and other nonprofit organizations (NPO). Specifically, of the different types of NPO according to their main economic activity (see the classification of Ruíz Olabuénaga, 2000), it was just possible to include those works that had analysed relationship models between businesses and universities, because of they were the only models which had also been dealt with empirically in the Relationship Marketing literature. The works that have studied this connection are those of Plewa and Quester (2006, 2007, 2008), Navarro et al. (2009), and Frasquet et al. (2012). The key variables they have mentioned in this area are listed in Table 3.

Key variables mentioned in the Relationship Marketing literature on exchanges between businesses and other NPOs.

| Authors | Antecedents | Mediation | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plewa and Quester (2006) | Participation | Trust Commitment | Satisfaction |

| Plewa and Quester (2007) | Organizational compatibility Personal experience | Trust Commitment Integration | Satisfaction Intention to renew |

| Plewa and Quester (2008) | Participation Experience | Trust Commitment | Satisfaction |

| Navarro et al. (2009) | Satisfaction of firms | Commitment by firms Perceived Commitment by universities | Participation |

| Frasquet et al. (2012) | Communication | Trust Satisfaction Functional conflict | Commitment Collaboration |

At this point, it clearly had to be concluded that the number of papers in the Relationship Marketing literature focusing on exchanges between businesses and NGOs/NPOs is very limited. We therefore considered it necessary to explore the main factors proposed in some other type of “organization-organization” relationships. Specifically, we incorporated “business-business” relationship models given the greater number of studies in that field. In the following paragraph, we shall briefly describe those most frequently cited in the literature.

In 1987, Dwyer, Schurr and Oh proposed a framework for the management of relationships between buyers and sellers, employing concepts of Modern Contract Law. They emphasized the importance of three key variables in the development of those relationships: trust, commitment, and disengagement. Subsequently, Anderson and Narus (1990) designed a model which employed a number of key variables to explain satisfaction in the relationships between producers and distributors. These variables were cooperation, dependence, influence, conflict, functional conflict (measuring disagreements that the partners resolved amicably), communication, results of the relationship, and trust. In 1992, Anderson and Weitz proposed a model of relationships between producers and distributors in which commitment was the central concept. Later, in 1994, Morgan and Hunt set out their Commitment-Trust Theory which has served as the basis on which most subsequent work has been developed (Bordonaba and Polo, 2006; Suárez et al., 2006; Wittmann et al., 2009; among others). They proposed and validated empirically that commitment and trust, separate from power and dependence, were key concepts in achieving successful relational exchanges. These two concepts were positioned as key mediating constructs between five antecedents (relationship benefits, shared values, communication, opportunistic behaviour, and relationship termination costs) and five outcomes of the relationship (acquiescence, propensity to leave, cooperation, functional conflict, and uncertainty in decision making). However, despite the spread of this theory, other constructs have also been suggested as explaining successful relationships between businesses. Among them, there stands out the construct of “relationship quality”, comprising, in general terms, three dimensions: trust, commitment, and satisfaction (De Wulf et al., 2001; Woo and Ennew, 2004).

In view of the divergence in the literature, in 2006, Palmatier et al. conducted a meta-analysis aimed at testing empirically the relative effects on performance of commitment, trust, satisfaction, and the relationship quality. Their results indicated that the greatest influence corresponded to the constructs “relationship quality” and, to a lesser extent, “commitment”. This supported a multidimensional perspective of the relationship in which a single mediator, whether commitment, trust, or satisfaction, could not by itself capture the full essence of a relationship. More than one construct of relational mediation had therefore to be included. In order to gain further insight into the main mediating constructs of successful interfirm exchanges, in 2007, Palmatier, Dant and Grewal compared Commitment-Trust Theory with another three dominant theories at that time – Dependence Theory, Transaction Cost Theory, and Relational Norms Theory. The results of their empirical study showed that the “commitment-trust” binomial indeed played a key role in explaining successful interfirm exchanges.

Given the relative scarcity of studies based on Relationship Marketing Theory in the specific field of the present work, and the importance of Commitment-Trust Theory in all types of exchanges that have been analysed, it was considered appropriate to take the model of Morgan and Hunt (1994) as the basis on which to construct our model of relationship success. Since Morgan amd Hunt's model was initially proposed for an interfirm context, we adapted it to the present study's context by taking into account the Relationship Marketing literature and the studies on Cross-Sector Social Alliances (see Fig. 1).

A success model business-NGO partnership processes. Note: The solid arrows indicate direct positive relationships and the dashed arrow direct negative relationships between the given pair of variables.

Source: Adapted from Morgan and Hunt (1994).

As can be seen, success of business-NGO partnership processes could depend, directly or indirectly, on seven key variables. The literature on business-NGO partnership processes has enormously mentioned the importance of these variables in the success of such partnership processes:

- •

Opportunistic Behaviour (Das and Teng, 2000; Rondinelli and London, 2003; Graf and Rothlauf, 2012). According to these authors, successful collaboration processes are characterized by the absence of opportunistic behaviour, i.e., the absence of behaviours by partners seeking to maximize their own interests to the detriment of others.

- •

Shared Values (Bryson et al., 2006; Austin and Seitanidi, 2012b; Gray and Stites, 2013). Following these authors, the identification of values that are shared among the partners, for example, expressed through the initial articulation of the social problem that affects both partners, are a key for the avoidance of the appearance of conflict, and therefore to ensure the success of the partnership processes.

- •

Commitment (Rondinelli and London, 2003; Berger et al., 2004; Seitanidi, 2010; Jamali et al., 2011; Graf and Rothlauf, 2012). The partners’ full and active commitment to the objectives set out in the partnership process is a key factor for success in achieving mutual benefits and added value.

- •

Trust (Berger et al., 2004; Bryson et al., 2006; Yaziji and Doh, 2009; Wilson et al., 2010; Dahan et al., 2010; Rivera-Santos and Rufín, 2010; Jamali et al., 2011; McDonald and Young, 2012; Graf and Rothlauf, 2012; Gray and Stites, 2013). Trust between the partners is transcendental throughout the partnership process (Berger et al., 2004). According to Bryson et al. (2006), trust is like the glue holding any collaboration together, facilitating working together and sustaining the alliance over time.

- •

Learning Together (Austin, 2000; Rondinelli and London, 2003; Senge et al., 2006). These authors observe that the partners’ learning together about the partnership process (Austin, 2000), which only takes place in a climate of respect, trust, and openness (Senge et al., 2006), is fuelled by their desire to generate more value in the partnership.

- •

Cooperation (Austin, 2000; Wilson et al., 2010). According to Wilson et al. (2010), cooperation allows resources to be combined efficiently in working towards the partnership's objectives. Cooperation is thus a key enabler of the success of social alliances (Wilson et al., 2010).

- •

Functional Conflict (Seitanidi, 2010; Gray and Stites, 2013). According to these authors, in spite of the fact that in these types of collaborations, conflicts may arise due to the presence of different values among partners, their amicable management is not only a key to the success of the partnership processes, but may also lead to the partners being able to take advantage of those differences.

Therefore, the following were the main changes that were made to the initial model of Morgan and Hunt (1994):

- •

Addition of new constructs. Due to its importance in the context of the present study, it was considered advisable to incorporate the construct “relationship learning” as a result of the Commitment-Trust binomial (Selnes and Sallis, 2003; Ling-Yee, 2006). It comprises three sub-processes: exchange of information, common interpretation of the shared information, and integration of knowledge.

- •

Elimination of constructs. Firstly, due to their lack of relevance to the context of the present study, it was considered appropriate to eliminate the following constructs from consideration: relationship termination costs, acquiescence, propensity to leave, and uncertainty in decision making. And secondly, incompatibilities with the new constructs that we had included led us to consider it necessary to exclude the following two constructs: the benefits of the relationship (already considered, albeit with another nomenclature, in the “success” construct of these processes of partnership) and communication (already considered in the model as an element of “relationship learning”, specifically in one of its sub-processes – exchange of information).

At a time characterized by the expansion of scientific production in all areas of research, “literature reviews” have become the indispensable link connecting the scientific work of the past with that of the future (Sánchez-Meca, 1999). Traditionally, these literature reviews have been characterized by a lack of any systematic approach to the decision-making they involve, by the presence of errors of interpretation, or by subjectivity throughout the process of their development (García and Brás, 2008). In response to this common practice, recent years have seen meta-analyses gaining great prominence as a new methodological approach with which to endow literature reviews with the rigour, objectivity, and systematization necessary to fruitfully gather together the scientific knowledge generated up to that time (Sánchez-Meca, 1999).

Therefore, meta-analyses have become established as key methodological tools to quantitatively integrate research findings of a large number of primary studies (Geyskens et al., 2009). By combining the results of these studies into a single estimate, meta-analyses, beyond overcoming difficulties associated with such primary studies, such as sampling error or measurement error, enable an analyst to test hypotheses that were not testable in these studies (Eden, 2002), and thus arrive at more accurate conclusions (Hunter and Schmidt, 2004).

Every meta-analysis involves a necessary series of steps (Sánchez-Meca et al., 2013):

- •

Formulation of the problem. First, the object of inquiry must be clearly delimited. This is generally the magnitude of some relationship between two variables or concepts (Sánchez-Meca, 2008).

- •

Literature search. Second, the studies to include in the meta-analysis must be located. To this end, it is necessary to specify a set of search criteria that these studies have to meet, for instance, the time range during which they were carried out.

- •

Coding of studies. Third, for each study, the attributes that could affect the results of the meta-analysis need to be extracted.

- •

Choice of effect size metric. Fourth, it is necessary to define the size of the effect, by means of a quantitative metric reporting the magnitude of the relationship found in each study (Sánchez-Meca, 2008).

- •

Statistical analysis and interpretation. Fifth, techniques of statistical analysis are applied that are specifically designed to process this type of data.

- •

Publication. And sixth, the results need to be disseminated.

The set of hypotheses that appear in the proposed success model of the present work were subjected to a meta-analysis following the above series of steps.

Search process and coding of studiesThe key impetus for Relationship Marketing research was Dwyer et al. (1987) seminal article (Palmatier et al., 2006). Therefore, we performed a search for empirical articles on the relationships posited in our success model proposal spanning the time period of 1987–2012. Moreover, the search process involved several choices, which we outline below. The first choice made was to include only published journal articles, thereby excluding book chapters or unpublished work. Journal articles have been through a review process that acts as a screen for quality, allowing us to include works meeting a certain level of conceptual and methodological rigour (David and Han, 2004; Newbert, 2007). The second choice made was to use both the ABI/Inform Complete and Academic Search Complete databases as search tools. The reasons were their extensive full-text coverage of academic journals, and their multidisciplinary nature. This latter aspect allowed searches to be made in multiple fields at the same time, including the field of Marketing, the object of the present study. Our next task was to select a sample of articles from over 1 million articles compiled in these databases. The following search process was followed: the selected articles had to include the names of the variables in question1 in the title, abstract, or keywords; and the name of the theory (“relationship marketing”) in any field. In this regard, it should be highlighted, that if the number of articles retrieved from the database in question was high (>100), two additional filters would be applied: (1) since we were taking “business-business” relationship variables and analysing their links in “business-NPO” relationships, the articles had to be framed in a “business-business” or “business-NPO” context; and (2) the articles had to be empirical, since otherwise we would be unable to perform the necessary calculations for the meta-analysis.

For each relationship, the articles which passed this set of filters were then examined. This reading allowed us on the one hand to eliminate those articles which were irrelevant for the objectives of the present study (articles in which the variables in question were encompassed in other more general constructs, or were related by means of indirect links), and, on the other, by following citations-to and citations-from, incorporating new articles into the present study's database. The result was a set of 76 valid articles (Table 4). From these, it was possible to evaluate a total of 121 estimated effect sizes.2 The number of estimated effect sizes per relationship was similar to those obtained in other meta-analyses in the field of Relationship Marketing Theory (see Palmatier et al., 2006). The data of the final 76 articles were input into an Excel spreadsheet with the following settings: (1) author; (2) year; (3) publication; (4) type of relationship (“business-business” or “business-NPO”); and (5) statistical techniques used.

Articles included in the meta-analysis.

| Authors | Year | Journal | Relationship Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Afonso et al. | 2011 | Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Anderson and Narus | 1990 | Journal of Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Armstrong and Yee | 2001 | Journal of International Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Barnes et al. | 2011 | Industrial Marketing Management | “Business-business” |

| Barnes et al. | 2010 | Journal of International Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Bordonaba and Polo | 2008 | Journal of Strategic Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Bordonaba and Polo | 2008 | Journal of Marketing Channels | “Business-business” |

| Brencic et al. | 2008 | Nase Gospodarstvo | “Business-business” |

| Bühler et al. | 2007 | International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship | “Business-business” |

| Burkert et al. | 2012 | Industrial Marketing Management | “Business-business” |

| Cater and Cater | 2009 | The Service Industries Journal | “Business-business” |

| Chadwick and Thwaites | 2006 | International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship | “Business-business” |

| Chang and Gotcher | 2008 | International Journal Technology Management | “Business-business” |

| Chen et al. | 2008 | Supply Chain Management: An International Journal | “Business-business” |

| Chen et al. | 2009 | Journal of Relationship Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Chenet et al. | 2010 | Journal of Services Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Chumpitaz and Paparoidamis | 2007 | European Journal of Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Costa et al. | 2012 | International Business Review | “Business-business” |

| Coulter and Coulter | 2002 | The Journal of Services Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Doney et al. | 2007 | European Journal of Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Duarte and Davies | 2004 | Journal of Marketing Channels | “Business-business” |

| Duhan and Sandvik | 2009 | International Journal of Advertising | “Business-business” |

| Eckerd and Hill | 2012 | International Journal of Operations and Production Management | “Business-business” |

| Eng | 2006 | Industrial Marketing Management | “Business-business” |

| Eser | 2012 | International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management | “Business-business” |

| Farrelly and Quester | 2003 | European Journal of Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Frasquet et al. | 2012 | High Education | “Business-NPO” |

| Gil-Saura et al. | 2009 | Industrial Management and Data Systems | “Business-business” |

| Giunipero et al. | 2012 | Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice | “Business-business” |

| Ha | 2010 | Asian Business and Management | “Business-business” |

| Huang and Chang | 2008 | Journal of Intellectual Capital | “Business-business” |

| Jap | 1999 | Journal of Marketing Research | “Business-business” |

| Jap and Ganesan | 2000 | Journal of Marketing Research | “Business-business” |

| Jean and Sinkovics | 2010 | International Marketing Review | “Business-business” |

| Jean et al. | 2010 | Journal of International Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Jena et al. | 2011 | Journal of Indian Business Research | “Business-business” |

| Johnson et al. | 1996 | Journal of International Business Studies | “Business-business” |

| Joshi | 2012 | Journal of Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Joshi and Stump | 1999 | Academy of Marketing Science | “Business-business” |

| Kim et al. | 2009 | Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Lancastre and Lages | 2006 | Industrial Marketing Management | “Business-business” |

| Levy et al. | 2009 | International Advances in Economic Research | “Business-business” |

| Ling-Yee | 2006 | Industrial Marketing Management | “Business-business” |

| Ling-Yee | 2007 | Journal of Marketing Channels | “Business-business” |

| MacMillan et al. | 2005 | Journal of Business Research | “Business-NPO” |

| Morgan and Hunt | 1994 | Journal of Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Nicholson et al. | 2001 | Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science | “Business-business” |

| Palmatier et al. | 2007 | Journal of Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Palmatier et al. | 2007 | Journal of Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Payan | 2006 | The Marketing Management Journal | “Business-business” |

| Payan and Svensson | 2007 | Journal of Marketing Management | “Business-business” |

| Pesämaa and Franklin | 2007 | Management Decision | “Business-business” |

| Pimentel et al. | 2006 | Supply Chain Management: An International Journal | “Business-business” |

| Plewa | 2009 | Australasiam Marketing Journal | “Business-NPO” |

| Plewa and Quester | 2007 | Journal of Services Marketing | “Business-NPO” |

| Racela et al. | 2007 | International Marketing Review | “Business-business” |

| Rindfleisch | 2000 | Marketing Letters | “Business-business” |

| Ruiz and Gil | 2012 | Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, | “Business-business” |

| Ryssel et al. | 2004 | The Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Salciuviene et al. | 2011 | Baltic Journal of Management | “Business-business” |

| Sang and Hyung | 2008 | Industrial Marketing Management | “Business-business” |

| Sarkar et al. | 2001 | Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science | “Business-business” |

| Selnes and Sallis | 2003 | Journal of Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Sichtmann and Von Selasinsky | 2010 | Journal of International Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Siguaw et al. | 1998 | Journal of Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Skarmeas et al. | 2002 | Journal of International Business Studies | “Business-business” |

| Smith and Barclay | 1999 | Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management | “Business-business” |

| Theron et al. | 2008 | Journal of Marketing Management | “Business-business” |

| Ulaga and Eggert | 2006 | European Journal of Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Walter and Ritter | 2003 | The Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Wiley et al. | 2005 | Australasian Marketing Journal | “Business-business” |

| Wong et al. | 2008 | Journal of Services Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Yang and Lai | 2012 | Journal of Business Research | “Business-business” |

| Zabkar and Makovec | 2004 | International Marketing Review | “Business-business” |

| Zhao and Wang | 2011 | Journal of Strategic Marketing | “Business-business” |

| Zineldin and Jonsson | 2000 | The TQM Magazine | “Business-business” |

As the principal effect size metric, we shall use the correlation coefficient r. This is because it is the commonest metric used both in the articles analysed (>75%)3 and in previous meta-analyses in the marketing field (see Palmatier et al., 2006; Augusto and Vargas, 2008). In this sense, for the articles which did not directly provide correlation coefficients, but coefficients from regression or structural equation models, we followed the steps recommended by other authors (Peterson and Brown, 2005; Bowman, 2012).

First, Bowman (2012) recommends converting the adjusted standardized beta coefficients (which appear in structural equation models), to unadjusted standardized beta coefficients (which appear in regression models) using the following formula:

where βunadjusted is the unadjusted standardized beta coefficient, βadjusted is the adjusted standardized beta coefficient (which appears in the structural equation model), rXX is the internal reliability of the relevant independent variable, and rYY is the internal reliability of the dependent variable.Second, Peterson and Brown (2005) suggest transforming the standardized regression (beta) coefficients into correlation coefficients using the following equation:

where λ is an indicator variable that equals 1 when β is nonnegative and 0 when β is negative. The use of the proposed formula is restricted to values of β between −0.5 and +0.5.To check that the mean levels of correlation were the same for the two groups (the studies that provided correlation directly, and the studies whose correlations were obtained indirectly from their standardized regression coefficients), a t-test assuming equal variances was applied. The results confirmed that there were no significant differences between the two groups for the links in question at a significance level of 5%.

Statistical analysisThe literature on methods of meta-analysis allows the researcher various options. In the present case, we considered it appropriate to follow the procedure of Hunter and Schmidt (1990) as perfectly described by Sánchez-Meca (1999).

Firstly, we calculated the weighted mean of the empirical correlations using Eq. (3) below, and then the observed total variance of the empirical correlations using Eq. (4). Since the studies used in the meta-analysis had sampling and measurement errors, we also calculated the sampling error variance using Eq. (5) (Hunter and Schmidt, 1990).

where Ni is the sample size of the ith study, ri is the empirical correlation of the ith study, r¯ is a weighted mean of the empirical correlations, and N¯ is the mean sample size (N¯=∑Ni/k where k is the number of studies).Once having estimated the observed variance and the sampling error variance, we checked whether the empirical correlations were homogeneous (that is, if the observed variance was mainly due to the statistical artefact of the error variance, or if, on the contrary, part of the observed variance was due to the influence of moderating variable).

Hunter and Schmidt (1990) propose two statistical tests for this purpose. The first is to apply the “75% rule” whereby, if at least 75% of the observed variance corresponds to sampling error variance, then the hypothesis that there is true variance between the empirical correlations can be rejected, and one can conclude that the correlations of the studies are homogeneous. If, however, the sampling error variance fails to explain that percentage, then one must assume that there exist moderating variables that are affecting the empirical correlations, and that therefore the homogeneity hypothesis does not hold. The 75% rule is calculated with the following expression:

The second method is to apply the Q statistic using the following expression:

The Q statistic is distributed according to a Pearson's χ2 law with k−1 degrees of freedom. Thus, with α being the significance level adopted for the test, if the value given by Eq. (5) exceeds the 100(1−α) percentile of the distribution then the homogeneity hypothesis does not hold, and one should therefore proceed to seek moderating variables that explain the observed heterogeneity.

Finally, if the set of correlation coefficients are homogeneous then one can estimate the population correlation with a confidence interval given by the following expression:

The statistical analysis described above was applied for each of the links proposed in the success model both for the general case and, where possible, for the “type of relationship” aggregate. As will be discussed in the following subsection, these calculations allowed a more detailed analysis with comparisons within aggregates and in relation to the general case.

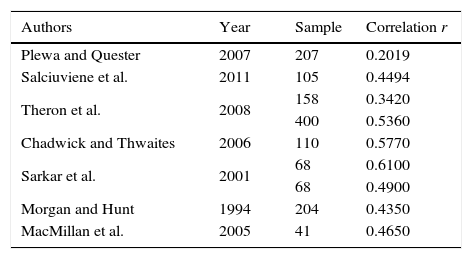

Interpretation of resultsTables 5 and 6 present details of the results for each of the links considered in the meta-analysis.

Results of the meta-analysis.

| Linka | Analysis group | k | N | r¯ | Sr2 | Se2 | 75% rule | Q statistic | χ2 | Intervals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||||||

| SV-CM | General | 9 | 1361 | 0.443 | 0.015 | 0.004 | 27.63 | 32.56 | 15.51 | 0.4 | 0.48 |

| Business-business | 7 | 1113 | 0.487 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 50 | 14 | 12.59 | 0.44 | 0.53 | |

| Business-NPO | 2 | 248 | 0.245 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 75.19 | 2.65 | 3.84 | 0.12 | 0.36 | |

| SV-TR | General | 11 | 2068 | 0.373 | 0.047 | 0.003 | 8.33 | 132.03 | 18.31 | 0.33 | 0.41 |

| OB-TR | General | 8 | 1735 | −0.472 | 0.03 | 0.002 | 9.06 | 88.29 | 14.07 | −0.43 | −0.5 |

| TR-CM | General | 25 | 5585 | 0.573 | 0.012 | 0.002 | 16.13 | 154.92 | 36.4 | 0.55 | 0.59 |

| Business-business | 22 | 4932 | 0.582 | 0.012 | 0.002 | 15.23 | 144.42 | 32.7 | 0.56 | 0.6 | |

| Business-NPO | 3 | 653 | 0.506 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 48.5 | 6.18 | 5.99 | 0.44 | 0.56 | |

| TR-CP | General | 19 | 4115 | 0.555 | 0.019 | 0.002 | 11.65 | 163 | 28.9 | 0.53 | 0.57 |

| CM-CP | General | 8 | 1452 | 0.655 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 30.7 | 26.05 | 14.07 | 0.62 | 0.68 |

| TR-RL | General | 5 | 1274 | 0.621 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 26.66 | 18.75 | 9.48 | 0.58 | 0.65 |

| CM-RL | General | 4 | 1162 | 0.513 | 0.027 | 0.001 | 6.94 | 57.61 | 7.81 | 0.47 | 0.55 |

| TR-FC | General | 1 | 204 | 0.406 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| FC-SC | General | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| RL-SC | General | 8 | 2253 | 0.538 | 0.018 | 0.001 | 9.73 | 82.17 | 14.07 | 0.5 | 0.56 |

| CP-SC | General | 9 | 1996 | 0.245 | 0.03 | 0.003 | 13.21 | 68.11 | 15.51 | 0.2 | 0.28 |

| CM-SC | General | 14 | 4171 | 0.544 | 0.048 | 0.001 | 3.44 | 406.3 | 22.36 | 0.52 | 0.56 |

| Business-business | 12 | 3840 | 0.566 | 0.046 | 0.001 | 3.1 | 386.77 | 19.67 | 0.54 | 0.58 | |

| Business-NPO | 2 | 331 | 0.294 | 0.0003 | 0.005 | 1444.46 | 0.13 | 3.84 | 0.19 | 0.39 | |

Summary of the main results.

| Link | rmin | rmax | r¯ | Degree of correlation | Evidence for moderating variables | Moderation by “type of relationship” | Evidence for mod. variables in business-NPO relationship | Justification of the hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedents/mediation variables | ||||||||

| SV-CM | 0.20 | 0.61 | 0.44* | HIGH | YES | r¯E−E=0.48* r¯E−NPO=0.24* | NO | YES |

| SV-TR | 0.14 | 0.74 | 0.37* | MEDIUM | YES | ** | ** | YES |

| OB-TR | −0.25 | −0.75 | −0.47* | HIGH | YES | ** | ** | YES |

| Mediation variables | ||||||||

| TR-CM | 0.36 | 0.79 | 0.57* | HIGH | YES | r¯E−E=0.58* r¯E−NPO=0.50* | YES | YES |

| Mediation variables/outcome variables | ||||||||

| TR-CP | 0.32 | 0.79 | 0.55* | HIGH | YES | ** | ** | YES |

| CM-CP | 0.49 | 0.74 | 0.65* | HIGH | YES | ** | ** | YES |

| TR-RL | 0.50 | 0.74 | 0.62* | HIGH | YES | ** | ** | YES |

| CM-RL | 0.32 | 0.70 | 0.51* | HIGH | YES | ** | ** | YES |

| TR-FC | – | – | – | – | – | ** | ** | Insufficient number of studies |

| Outcome variables/success variable | ||||||||

| FC-SC | – | – | – | – | – | ** | ** | Insufficient number of studies |

| RL-SC | 0.40 | 0.76 | 0.53* | HIGH | YES | ** | ** | YES |

| CP-SC | −0.05 | 0.61 | 0.24* | LOW | YES | ** | ** | YES |

| CM-SC | 0.22 | 0.79 | 0.54* | HIGH | YES | r¯E−E=0.56* r¯E−NPO=0.29* | NO | YES |

The “shared-values-commitment” link presents effect sizes (r) between 0.20 and 0.61 for a set of 9 samples, corresponding to an aggregate of 1361 persons. Eq. (3) gives a mean r value of 0.44. According to the scale established by Cohen (1988) for the social sciences, correlations with absolute values of r close to 0.5 correspond to a large effect size, and reflect the real existence of the phenomenon. The 95% confidence interval (Hunter and Schmidt, 1990) does not include zero (see Table 5, column “Intervals”), which allows one to consider that the mean correlation found is significant. Thus, one can state that, in the general case, there is a positive, significant, and moderately strong relationship for this link. In accordance with the procedures of searching for moderators (Hunter and Schmidt, 1990), the 75% threshold rule, and the Q test, the data lead to the conclusion that the observed variability is not only due to sampling error variance but that there have to be moderating variables affecting it. The next step, therefore, was to search for moderating variables. Since the present study takes the variables from the “business-business” field and analyses their linkages in the “business-NPO” field, we examined whether the level of correlation depended on the context. To this end, we selected the “type of relationship” as a moderating variable with the following two categories: “business-to-business” and “business-NPO”. The resulting mean correlation in studies focusing on “business-business” relationships (r¯=0.487) was significantly higher than that of the “business-NPO” studies (r¯=0.245), demonstrating that this variable affects the magnitude of the correlation between the two variables, even though the “shared values-commitment” correlation is significant in both cases, as shown by the corresponding confidence intervals. Regarding evidence for moderators, it is interesting that in the case of the “business-business” relationships there must be other potentially moderating variables because a percentage (in particular, 25%) of the observed variance remains to be explained. In the “business-NPO” case, there was no evidence for moderators, but with so few studies the data need to be interpreted with caution.

The “shared values-trust” link presents effect sizes (r) between 0.14 and 0.74 for a set of 11 samples, corresponding to an aggregate of 2068 persons. Eq. (3) gives a mean r value of 0.37. According to the scale established by Cohen (1988), correlations with absolute values of r close to 0.3 correspond to a moderate effect size for the real existence of the phenomenon. The 95% confidence interval (Hunter and Schmidt, 1990) does not include zero (see Table 5, column “Intervals”), which allows one to consider that the mean correlation found is significant. In accordance with the procedures of searching for moderators (Hunter and Schmidt, 1990), the data lead to the conclusion that the observed variability is not only due to sampling error variance but that there have to be moderating variables affecting it. However, since for this link we found no literature studies focusing on “business-NPO” relationships, no analysis could be made of the influence of the “type of relationship”.

The “opportunistic behaviour-trust” link presents effect sizes (r) between −0.25 and −0.75 for a set of 8 samples, corresponding to an aggregate of 1735 persons. Eq. (3) gives a mean r value of −0.47. According to the scale established by Cohen (1988), correlations with absolute values of r close to 0.5 correspond to a large effect size, and reflect the real existence of the phenomenon. The 95% confidence interval (Hunter and Schmidt, 1990) does not include zero (see Table 5, column “Intervals”), which allows one to consider that the mean correlation found is significant. In accordance with the procedures of searching for moderators (Hunter and Schmidt, 1990), the data lead to the conclusion that the observed variability is not only due to sampling error variance but that there have to be moderating variables affecting it. However, since for this link we found no literature studies focusing on “business-NPO” relationships, no analysis could be made of the influence of the “type of relationship”.

The foregoing methodological procedure, used to draw conclusions about the significance and strength of relationships between the model's antecedent and mediating variables, was applied to the rest of the relationships conforming the model's hypotheses. Table 6 presents a synthesis of the most interesting results of the meta-analytic study for all the links posited in the relational model.

As can be seen, the results confirm the existence of moderately strong correlations for all but two of the links in the model. The two exceptions were cases of there being insufficient literature to perform the calculations. Also, the presence of moderating effects was detected in all the links. In the three cases for which there were sufficient studies to make further analysis possible, we examined the possible moderating effect of the “type of relationship” variable. There were found to be considerable differences in the results reported by studies of “business-business” relationships and by those whose focus was on the “business-NPO” context. In particular, the mean correlations were weaker in this latter group of studies for all three cases, showing that the type of alliance with which a study is conducted affects the magnitude of the correlation between the variables. In future studies that include an empirical analysis of “business-NPO” relationships, the possibility needs to be borne in mind that the correlations found will be weaker than those obtained in other partnership contexts, without this having to be cause for particular concern because it appears to be a natural characteristic of this type of alliance.

Conclusions and implications for managementConclusionsThe principal objective of the present work has been to propose a model of success of business-NGO partnership processes, analysing the theoretical consistency of each of its hypotheses by means of a meta-analysis of the pertinent studies in the Relationship Marketing literature.

The meta-analytical approach taken was that of the psychometric meta-analysis of Hunter and Schmidt (1990). In this approach, especial attention is paid to the inter-study variability of the results and to controlling for statistical artefacts that could bias the results. The selection of primary studies for the meta-analysis was both broad and deep so as to cover as much as possible of the range of publications contributing knowledge on the problem.

On the one hand, based on a “generalization of validity” perspective, we were able to determine the existence of significant and important correlations between each pair of constructs under analysis. The strongest correlations were found for the links “commitment-cooperation” (r¯=0.65) and “trust-relationship learning” (r¯=0.62).

On the other hand, analysis of the differential effects led to three new findings that contribute to enriching the existing literature. First, with respect to the links between antecedent and mediating constructs, it was confirmed that the construct “shared values” has different effects on the mediating constructs included in the proposed model. In particular, consistent with the work of Palmatier et al. (2006), “shared values” have a greater impact on “commitment” (r¯=0.44) than on “trust” (r¯=0.37). Second, with respect to the links between mediating and outcome constructs, the constructs “trust” and “commitment” have different effects on the model's outcome constructs. Specifically, “trust” has a greater impact on “relationship learning” (r¯=0.62) than on “cooperation” (r¯=0.55), while “commitment” has a greater influence on “cooperation” (r¯=0.65) than on “relationship learning” (r¯=0.51). And third, the most critical construct for improving the success of the partnership processes under study is “commitment” (r¯=0.54), supporting previous evidence for its key role in achieving mutual benefits and added value (Seitanidi, 2010; Jamali et al., 2011).

This set of findings, as will be seen below, has important implications for the managers of firms and nonprofits who wish to improve their partnership processes.

Finally, it is interesting to note that, to the extent that the inter-study variability of the effect size was not explicable by errors due to statistical artefacts, the analysis has confirmed the existence of moderating effects on the links that were studied. In this regard, where possible, we examined the influence of the moderating variable “type of relationship”, since, although our proposed success model is targeted at “business-NPO” alliances exclusively, for the meta-analysis we reviewed literature in both this field and that of “business-business” alliances. Of all the links, it was possible to perform this analysis for just three – “shared-values-commitment”, “trust-commitment”, and “commitment-success”. Only in the case of “trust-commitment”, was it impossible to explain all of the sampling error variance for business-NPO partnerships, leaving the challenge for future studies in the present research context to determine what other variables might exert a moderating effect on this link.

Implications for managementThis meta-analysis may be of great interest to those managers of firms and NPOs who wish to improve the short- or long-term success of their partnership processes.

The determination of the positive or negative magnitude of the set of links under study opens up the possibility of finding instruments or means with which to improve the management of these partnership processes. In particular, this study suggests fostering behaviours that strengthen the elements of the relationship that the present model proposes. In this regard, one would draw the attention of directors and managers of both types of entity to the possibility of defining the terms of their partnership processes in consonance with the relational elements that were found to be directly or indirectly related to making those processes more successful. Indeed, since “commitment” was found to be the most important relational element in terms of improving the success of the partnership processes, we would propose that management might work specifically on this aspect of their relationship.

Moreover, since the antecedents appear to operate through different mediators which affect the results of the relationship differentially, we would propose that managers of firms and nonprofits who wish to improve any of the outcome factors included in the proposed success model, should act on those marketing strategies (antecedents) that exert most influence on those mediators. On the one hand, for instance, managers who are looking to reach a greater degree of cooperation with their partners should recognize that commitment to the relationship is the most critical mediating element for getting this outcome. Generating greater commitment will involve the creation of more and better common reference points between the partners. This is because the creation of shared values between the partners showed itself to be a key marketing strategy for improving the existing commitment to a relationship. Nevertheless, another recommendation would be to first analyse the characteristics and values of the potential partner, the aim being to initiate partnerships only with those entities that are perceived to have, in principle, a greater level of shared values. On the other hand, managers who are looking to improve the existing level of relationship learning should recognize that trust is the most critical mediating element for improving this outcome. They thus must also work to prevent opportunistic behaviour in the relationship, since such prevention is the most important of the marketing strategies considered in the present analysis for improving trust between the partners.

In short, this study has demonstrated that the success of the processes of partnerships between businesses and nonprofits can be improved by adopting a deeper Relationship Marketing approach in which the managers of the two entities seek the specific strategies with which to successfully address the weaknesses of their own partnership processes.

Limitations and principal future lines of researchMeta-analytic studies offer the researcher major advantages, but, in using them, one has to bear in mind their inherent limitations (Rosenthal and DiMatteo, 2001). First, as in other meta-analytic studies (David and Han, 2004; Newbert, 2007), the present analysis was subject to the published availability of work collected in the principal electronic bibliographic databases. It therefore does not reflect unpublished research whose inclusion could alter the significance of some of the links under study. Second, the analysis included only studies that reported Pearson correlation coefficients and adjusted or unadjusted standardized beta coefficients. It may be extended in future studies by including works which, while not reporting this information, do present sufficient data for appropriate processing. And third, the small number of articles found which included data on certain of the links, especially those corresponding to “business-NPO” relationships, limited the power of the present study to reject evidence for the absence of moderating variables. The results for this type of link should therefore be interpreted with relative caution.

However, these limitations could suggest interesting lines for future research. For example, this analysis suggests that since some of the links posited in the proposed success model, namely “trust-functional conflict” and “functional conflict-success” have not been analysed, due to an insufficient number of primary studies, future research should give priority to analysing those links rather than repeating the analysis of links which already have sufficient support in the Relationship Marketing literature.

Furthermore, future works should extend the constructs included in the proposed success model by detecting, through meta-analytic approaches, new constructs on which business and NPO managers could act to improve their partnership processes’ success. Thus, although it has been shown that commitment to the relationship and trust play critical roles, further research could include new constructs, such as the relationship quality, whose role in improving the success of different partnership processes has been clearly demonstrated in the Relationship Marketing literature.

Finally, as already noted above, the heterogeneity existing among almost all the links posited in the model, even after including the “type of relationship” as moderating variable, highlights the need for additional research to determine if there are other potential moderating effects in the model. In this respect, in line with other meta-analyses (Geyskens et al., 1998; Camisón et al., 2002; Palmatier et al., 2007; García and Brás, 2008), this study suggests a priori as potential moderating variables the activity sector in which the firm operates (hostelry, retailing, banking, etc.), the age of the relationship, and the specific dimensions of the latent variables highlighted by the literature.

The authors of articles which did not provide correlation matrices were contacted by requesting that information.

The research results presented in this paper were obtained dealing with the pre-doctoral fellowship of the first co-author of this paper, María Jesús Barroso-Méndez (DOE130 08/07/2010), who is grateful to the Regional Ministry of Economy, Trade and Innovation of the Government of Extremadura and the European Social Fund.

A list of the references of the articles used in this meta-empirical analysis is available upon request from the authors.

| Authors | Year | Sample | Correlation r |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. | 2009 | 204 | 0.5247 |

| Armstrong and Yee | 2001 | 100 | 0.2058 |

| 100 | 0.1476 | ||

| Plewa and Quester | 2007 | 207 | 0.5108 |

| Johnson et al. | 1996 | 101 | 0.2200 |

| 101 | 0.2400 | ||

| Coulter and Coulter | 2002 | 677 | 0.1600 |

| Sarkar et al. | 2001 | 68 | 0.6600 |

| 68 | 0.6400 | ||

| Nicholson et al., | 2001 | 238 | 0.7400 |

| Morgan and Hunt | 1994 | 204 | 0.5190 |

| Authors | Year | Sample | Correlation r |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barnes et al. | 2010 | 202 | 0.7000 |

| Bordonaba and Polo | 2008 | 107 | 0.3680 |

| 102 | 0.7850 | ||

| Burkert et al. | 2012 | 297 | 0.4800 |

| Chumpitaz and Paparoidamis | 2007 | 234 | 0.7071 |

| Cater and Cater | 2009 | 150 | 0.4729 |

| Doney et al. | 2007 | 202 | 0.5800 |

| Farrelly and Quester | 2003 | 92 | 0.5520 |

| Frasquet et al. | 2012 | 322 | 0.5770 |

| Gil-Saura et al. | 2009 | 276 | 0.5780 |

| Ha | 2010 | 184 | 0.5916 |

| Lancastre and Lages | 2006 | 395 | 0.7200 |

| Pesämaa and Franklin | 2007 | 99 | 0.5900 |

| Palmatier et al. | 2007 | 396 | 0.6000 |

| Plewa | 2009 | 124 | 0.4773 |

| Plewa and Quester | 2007 | 207 | 0.4152 |

| Ruiz and Gil | 2012 | 304 | 0.6110 |

| Ryssel et al. | 2004 | 61 | 0.5080 |

| Ulaga and Eggert | 2006 | 400 | 0.6800 |

| Walter and Ritter | 2003 | 247 | 0.4500 |

| Wong et al. | 2008 | 202 | 0.4500 |

| Zabkar and Makovec | 2004 | 204 | 0.7950 |

| 216 | 0.4970 | ||

| Morgan and Hunt | 1994 | 204 | 0.5490 |

| Siguaw et al. | 1998 | 358 | 0.4000 |

| Authors | Year | Sample | Correlation r |

|---|---|---|---|

| Afonso et al. | 2011 | 163 | 0.61000 |

| Barnes et al. | 2011 | 208 | 0.43670 |

| Pimentel et al. | 2006 | 67 | 0.36000 |

| Duarte and Davies | 2004 | 887 | 0.71300 |

| Duhan and Sandvik | 2009 | 135 | 0.56000 |

| Eng | 2006 | 179 | 0.32930 |

| Eser | 2012 | 87 | 0.45376 |

| Ha | 2010 | 184 | 0.65570 |

| Jap | 1999 | 275 | 0.47000 |

| 220 | 0.39000 | ||

| Joshi and Stump | 1999 | 184 | 0.42000 |

| Lancastre and Lages | 2006 | 395 | 0.64000 |

| Payan | 2006 | 363 | 0.35000 |

| Payan and Svensson | 2007 | 166 | 0.67000 |

| Pesämaa and Franklin | 2007 | 99 | 0.79000 |

| Rindfleisch | 2000 | 106 | 0.47500 |

| Smith and Barclay | 1999 | 95 | 0.62000 |

| 98 | 0.53000 | ||

| Morgan and Hunt | 1994 | 204 | 0.58600 |

| Authors | Year | Sample | Correlation r |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bordonaba and Polo | 2008 | 102 | 0.77900 |

| Brencic et al. | 2008 | 225 | 0.29520 |

| Chenet et al. | 2010 | 302 | 0.69000 |

| Eckerd and Hill | 2012 | 110 | 0.79600 |

| Joshi | 2012 | 306 | 0.37000 |

| Palmatier et al. | 2007 | 396 | 0.22500 |

| Plewa and Quester | 2007 | 207 | 0.28030 |

| Plewa | 2009 | 124 | 0.31900 |

| Salciuviene et al. | 2011 | 105 | 0.34100 |

| Sang and Hyung | 2008 | 279 | 0.50000 |

| Sichtmann and Von Selasinsky | 2010 | 142 | 0.34640 |

| Skarmeas et al. | 2002 | 216 | 0.40600 |

| Wiley et al. | 2005 | 207 | 0.42100 |

| Jap and Ganesan | 2000 | 1450 | 0.78000 |

In line with other authors who have conducted meta-analyses (Palmatier et al., 2006; Arenas and García, 2006), for some variables we included alternative names mentioned in the literature:

- •

Shared Values/Similarity/Compatibility.

- •

Cooperation/Coordination/Joint Action*.

- •

Success/Performance/Satisfaction/Attainment of goal*/Fulfillment of objective*/Outcomes.

In line with other meta-analytic studies (Geyskens, Steenkamp and Kumar, 1998; Palmatier et al., 2006), when an article provided more than one estimated effect size for the same link and the same sample, we used their mean value. When the effect sizes were independent, however (i.e., from different samples), they were included as separate data.