The endogenous hyperinsulinemia hypoglucemic syndrome (EHHS) can be caused by an insulinoma, or less frequently, by nesidioblastosis in the pediatric population, also known as noninsulinoma pancreatic hypoglycemic syndrome (NIPHS) in adults.

The aim of this paper is to show the strategy for the surgical treatment of EHHS.

Materials and methodsA total of 19 patients with a final diagnosis of insulinoma or NIPHS who were treated surgically from January 2007 until June 2012 were included. We describe the clinical presentation and preoperative work-up. Emphasis is placed on the surgical technique, complications and long-term follow-up.

ResultsAll patients had a positive fasting plasma glucose test. Preoperative localization of the lesions was possible in 89.4% of cases. The most frequent surgery was distal pancreatectomy with spleen preservation (9 cases). Three patients with insulinoma presented with synchronous metastases, which were treated with simultaneous surgery. There was no perioperative mortality and morbidity was 52.6%. Histological analysis revealed that 13 patients (68.4%) had benign insulinoma, 3 malignant insulinoma with liver metastases and 3 with a final diagnosis of SHPNI. Median follow-up was 20 months. All patients diagnosed with benign insulinoma or NIPHS had symptom resolution.

ConclusionThe surgical treatment of EHHS achieves excellent long-term results in the control of hypoglucemic symptoms.

El síndrome hipoglucémico por hiperinsulinismo endógeno (SHHE) puede estar originado por un insulinoma o, menos frecuentemente, por la nesidioblastosis en niños, conocida en la población adulta con el nombre de síndrome hipoglucémico pancreático no insulinoma (SHPNI). El objetivo de este trabajo es mostrar la estrategia para el tratamiento quirúrgico del SHHE.

Material y métodoSe incluyó a un total de 19 pacientes con diagnóstico final de insulinoma o SHPNI que fueron tratados quirúrgicamente desde enero del 2007 hasta junio del 2012. Se describió la forma de presentación clínica y estudios preoperatorios. Se hizo hincapié en la técnica quirúrgica, las complicaciones y el seguimiento a largo plazo de los pacientes.

ResultadosTodos los pacientes en estudio tuvieron un test de ayuno positivo. Las lesiones que originaron el SHHE pudieron ser localizadas preoperatoriamente en el 89,4% de los casos. La cirugía más frecuente fue la pancreatectomía distal con preservación de bazo (9 casos). Tres pacientes con diagnóstico de insulinoma se presentaron con metástasis sincrónicas, que fueron tratadas con cirugía simultánea. No tuvimos mortalidad perioperatoria y la morbilidad fue del 52,6%. El análisis histolo¿gico revelo¿ que 13 pacientes (68,4%) presentaban insulinoma benigno, 3 insulinoma maligno con metástasis hepáticas y 3 con diagnóstico final de SHPNI. La mediana de seguimiento fue de 20 meses. Todos los pacientes con diagnóstico de insulinoma benigno o SHPNI resolvieron el síndrome de SHHE.

ConclusiónEl tratamiento quirúrgico del SHHE logra excelentes resultados a largo plazo en el control de los síntomas de hipoglucemia.

Endogenous hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia syndrome (EHHS) usually presents with neuropsychiatric symptoms, including: confusion, affected vision, trembling, palpitations, anxiety, amnesia and convulsions, which can lead to loss of consciousness and even coma.1 There are 2 pathological situations that can generate this syndrome. The most frequent is caused by pancreatic tumors, known as insulinomas; and secondly, hyperplasia of the beta cells in the pancreatic islets, commonly defined as nesidioblastosis in children and as non-insulinoma pancreatogenous hypoglycemia syndrome (NIPHS) in adults.

Insulinomas are the most frequent functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Their incidence in the general population is estimated at 1-4 per 1,000,000, annually.2 Extrapancreatic variations are extremely rare. The usual form of presentation is a small tumor (<2cm) that is hypervascularized, solitary, with a benign behavior and sporadic presentation. They are rarely associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) syndrome. Variations with multiple tumors and malignant types are uncommon (<10%).3 Preoperative localization with imaging methods is useful for planning surgical procedures. Medication can control the symptoms associated with hypoglycemia in approximately 50% of patients. However, surgery represents the treatment of choice for this type of neoplasms.

Nesidioblastosis is a congenital disorder that most commonly affects children and is characterized by hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the pancreatic islets, with early symptoms in infants. The adult form is a rare hypoglycemia syndrome characterized by diffuse hyperfunction of the beta cells of the pancreas, with clinical manifestations of postprandial neuroglycopenia and a 72-h fast test that can be either positive or negative.4 The topographic diagnosis can be carried out by means of a selective stimulation test with calcium.5

The objective of this study is to explain the strategy for the diagnosis and the surgical treatment of EHHS.

Materials and MethodsThis is a retrospective descriptive study that included a group of 19 consecutive patients operated on at the Hospital Italiano of Buenos Aires (HIBA) from January 2007 to June 2012 with a final diagnosis of insulinoma or NIPHS.

Preoperative StudiesThe clinical suspicion of EHHS originated in all cases from episodes of severe hypoglycemia. The definitive diagnosis was achieved with a fasting test, which was either partial or complete. Plasma determinations for glycemia, insulin, circulating C-peptide at baseline and contrainsular hormones (HGH, cortisol) were performed. During the study, the patients were authorized to drink non-caloric liquids. Samples were taken of peripheral blood (for dosage of glycemia, insulin and peptide C) every 4-6h or when the patient presented symptoms. The test was considered finalized when glycemia fell below 45mg/dl or there were symptoms. The presence of symptoms with the following criteria was diagnostic for EHHS: glycemia levels ≤45mg/l, insulin level >3μU/ml.

The imaging methods that were used before surgery to locate this type of tumors included: multidetector CT and angiography combined with a selective stimulation test with calcium gluconate or Doppman.6

The operative location and confirmation was performed with intraoperative ultrasound in both the open and laparoscopic approaches.

Surgical Technique and ComplicationsResection of the pancreatic parenchyma (pancreatectomy with or without spleen preservation) was carried out in those cases where enucleation could not be done safely due to risk of injury to the main pancreatic duct, lesions that were not palpable and could not be identified with intraoperative ultrasound, or when malignancy was suspected.

For cases of liver metastases, the possibility of simultaneous resection was considered if the patients presented the following criteria:

- 1.

Acceptable surgical risk

- 2.

Absence of extrahepatic disease

- 3.

Possibility to resect more than 90% of the tumor load

- 4.

Liver remnant >30%

We used the Dindo-Clavien classification to stratify the complications and postoperative mortality within the first 30 days after surgery.7

We defined pancreatic fistula and stratification in accordance with the criteria of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula.8

PathologyAll the surgical specimens were analyzed, certifying the final histopathologic diagnosis of insulinoma or NIPHS, complemented with immunohistochemistry techniques and the determination of Ki-67 (Ki-67≤2%=benign or low-grade aggressivity; Ki-67 2-20%=intermediate-grade aggressivity; Ki-67>20%=high-grade aggressivity).9 The insulinomas were classified as benign or malignant based on the World Health Organization classification for neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas.10

The final diagnosis of NIPHS was made using the major or minor criteria that were previously published.11

Follow-upThe follow-up included periodical medical controls every 3 months during the first year, which entailed the evaluation of 16-h fasting glycemia and insulinemia; multidetector CT was used in patients with liver metastasis.

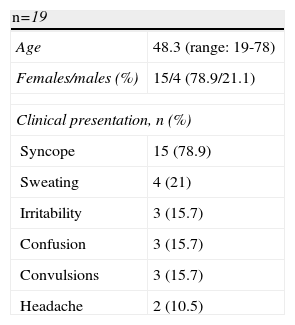

ResultsPatient Population and SymptomsNineteen patients were treated surgically with a diagnosis of EHHS at the HIBA, during the period indicated. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the patients and the symptoms at presentation: 16 patients with a diagnosis of insulinoma (84.2%) and 3 patients with a diagnosis of NIPHS (15.8%). Of the insulinomas, none presented a history of MEN-1. The average age at presentation was 48.3, with a predominance of women (79%).

Syncope (78.9%), sweating (15.7%), confusion (15.7%), irritability (16.6%) and convulsions (15.7%) were the most frequent symptoms at presentation.

The diagnosis of EHHS was based on the positivity of the 72-h fast test in 100% of patients.

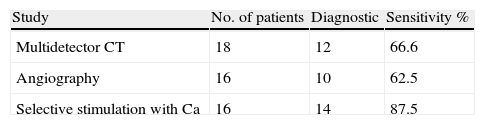

Preoperative Imaging MethodsPreoperative localization with non-invasive and invasive methods was possible in 89.4% (17/19) of cases (Table 2). The most frequently used non-invasive method was CT (94.7%), with a sensitivity of 66.6%.

Angiography alone was performed in 16 patients and showed a sensitivity for locating the tumor in 62.5%. The selective stimulation test with calcium was indicated in 16 patients (84.2%), with a sensitivity of 87.5%; it was the most sensitive study for locating or regionalizing the disease before surgery. Two patients (12.5%) were positive in more than one vascular territory (gastroduodenal artery and splenic artery), with a final pathologic diagnosis of NIPHS. Three patients did not undergo this study due to the suspicion of liver metastases.

Intraoperative Findings, Procedures and ComplicationsThe distribution of the lesions in the pancreatic parenchyma is summarized in Fig. 1. In the conventional and hand-assisted approaches, palpation detected a tumor in 92%. This maneuver was always complemented with intraoperative ultrasound (100% of the patients), with a sensitivity of 94.7% for both approaches (conventional and laparoscopic). This also enabled us to establish the relationship of the tumor with the main pancreatic duct in 92% of patients and to thus determine the type of surgery to carry out.

Conventional surgery was performed in 11 cases (57.9%). The laparoscopic approach was used in the remaining 8 (42.1%), with an effectiveness of 88.8% (only one converted patient). There was only one case in which hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery was used.

The most commonly performed surgical procedure was spleen-preserving pancreatectomy (9 cases), followed by corporocaudal splenopancreatectomy (7 cases) and 3 pancreatic enucleations. One patient had a positive fasting test, negative preoperative studies and negative intraoperative ultrasound, in whom blind distal pancreatectomy was performed (5%). Histopathology confirmed NIPHS.

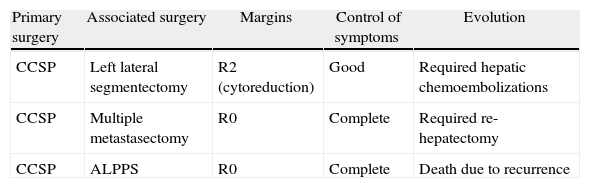

Three patients presented synchronous liver metastasis (15.7%), with selection criteria for simultaneous resections (Table 3).

Simultaneous Liver Resections.

| Primary surgery | Associated surgery | Margins | Control of symptoms | Evolution |

| CCSP | Left lateral segmentectomy | R2 (cytoreduction) | Good | Required hepatic chemoembolizations |

| CCSP | Multiple metastasectomy | R0 | Complete | Required re-hepatectomy |

| CCSP | ALPPS | R0 | Complete | Death due to recurrence |

ALPPS, Associated Liver Partition and Portal vein ligation for Staged hepatectomy; CCSP, corporocaudal splenopancreatectomy.

The operative time lasted an average of 168min (range: 120-240min). Mean hospital stay was 7 days (range: 4-80 days).

In this series, there was no perioperative mortality. In total, 10 patients presented complications (52.6%) (Table 4). The percentage of pancreatic fistula was 36%, 2 of which were grade A, 3 grade B and 2 grade C.

Complications and Treatment.

| Procedure | Complication | Treatment |

| CCSP | Pneumonia | Antibiotics |

| Pancreatectomy with spleen preservation | Fistula, grade A | Medication |

| CCSP | Hematoma bed | Medication |

| Pancreatectomy with spleen preservation | Fistula, grade A | Medication |

| Enucleation | Fistula, grade B | Medication |

| Laparoscopic pancreatectomy with spleen preservation | Fistula, grade B | Medication |

| Laparoscopic pancreatectomy with spleen preservation | Fistula, grade B | Medication |

| CCSP+ALPPS | Fistula, grade C+biliary | Percutaneous drain+CPRE |

| Laparoscopic enucleation | Fistula grade C+hemorrhage | Angiography |

| CCSP+left lateral segmentectomy lateral | Biliary fistula | Percutaneous drain |

ALPPS, Associated Liver Partition and Portal vein ligation for Staged hepatectomy; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; CCSP, corporocaudal splenopancreatectomy.

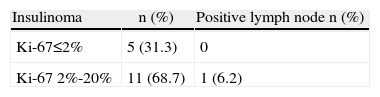

Histology analyses revealed that 13 patients (68.4%) presented benign insulinoma, and 3 (15.7%) were carriers of malignant insulinoma, with liver metastases. Table 5 provides the results of the Ki-67 analyses for insulinoma. All the patients with liver metastases presented a Ki-67>2%. Two patients presented with multiple tumors (10.5%). The final diagnosis of NIPHS was confirmed in 3 patients (15.7%). In 18 patients, the surgical margin was R0 and in only one patient it was R2.

Follow-upThe average follow-up of this study was 20 months (range: 1-70 months). All the patients with diagnosed benign insulinoma or NIPHS resolved the EHHS syndrome without presenting recurrences. As for the patients with diagnosis of malignant insulinoma, one of them died 6 months later due to recurrence of the disease. The other 2 patients were alive at the time this paper was written. One presented liver recurrence 11 months after the initial surgery. The other, who had undergone cytoreductive liver surgery, presented a good control of the hypoglycemic symptoms and received hepatic chemoembolization.

DiscussionThere are numerous articles regarding the management of EHHS. However, the majority of these reports are based on small patient populations due to the low incidence of these diseases. The recommendations for studying these patients, the most appropriate surgical technique and the prognostic factors present a low level of scientific evidence. Our study analyses a small population of patients compared with other series.12,13 Nevertheless, unlike these other experiences that took place over long periods of time, (25 years), our study encompasses a short period of time (5 years), using the same diagnostic and therapeutic protocols.

The gold-standard for the definitive diagnosis of EHHS is a positive 72-h fast test.14,15 NIPHS is a clinical challenge due to its differentiation with insulinoma, since the signs and symptoms at presentation for both diseases are usually similar.

Preoperative localization or regionalization with non-invasive and invasive methods was possible in 89.4% of the cases presented in this series. Multidetector CT provided direct correlation between the tumor and the rest of the pancreatic parenchyma. As it is a non-invasive study, it can be considered a first line approach for the morphologic characterization of this type of pathologies, with a sensitivity higher than 80%.12,13 There are other methods, such as magnetic resonance or endoscopic ultrasound, with sensitivities and specificities close to 100%.16

The selective stimulation test with calcium gluconate was the most sensitive preoperative study (87.5%) for locating or regionalizing the disease. This study is able to identify those regions of the pancreas with hyperactivity of the beta cells5 and is a guideline for the surgical resection of those regions of the pancreas that demonstrate greater activity.17 It is striking that 2 patients (12.5%) were positive in more than one vascular region (gastroduodenal artery and splenic artery), with a final diagnosis of NIPHS.

In all the patients, intraoperative ultrasound was used and was diagnostic in 94%. This method was also utilized to define surgical strategies (enucleation versus pancreatectomy) as it was able to establish the relationship between the tumor and main pancreatic duct.

A great dilemma may arise when the intraoperative location of the tumor cannot be achieved. In the series, we had one case with positive fasting test and negative preoperative studies. The intraoperative ultrasound could not define the lesion, so we performed a blind pancreatectomy. The final diagnosis confirmed NIPHS. There are reports of blind resections with a frequency of 5%.18

The conventional (open) approach was the most commonly used (58%), but in recent years, as we were acquiring more experience with the laparoscopic approach, there was a trend toward its use and only one patient had conversion in the entire series.

The literature does not clearly establish which surgery is best for this type of tumors. In the case of insulinomas, enucleation is usually the most frequently performed procedure (34%-74%).12,18,19 The percentage of the lesions that are situated in the head of the pancreas can reach 40%.20 In our series, however, only 2 patients (10%) presented this location; they were able to be enucleated, thus avoiding a pancreaticoduodenectomy.

In this series, due to the relationship of the tumor with the main pancreatic duct, pancreatectomy either with or without preservation of the spleen was the most common procedure. There were other causes that required us to carry out more radical surgery, such as the presence of liver metastases associated with the primary tumor or multiple lesions. In the case of NIPHS, the procedure of choice was distal pancreatectomy, just as in other publications,13,15 because it is a diffuse disease that is most commonly located in the distal portion of the gland.

The resolution of the EHHS symptoms was attained in 100% of the patients with benign disease (benign insulinoma or NIPHS) by means of surgical treatment.

We had 3 patients who presented synchronous liver metastases and underwent resection of the primary tumor as well as the liver metastases (simultaneous resection). In the intraoperative ultrasound evaluation, one of them presented more extensive liver disease than expected after the preoperative studies (with a liver remnant <30%). It was therefore decided to carry out a right liver partition in situ with portal ligation in order to avoid postoperative liver failure.21

There was no perioperative mortality in the entire series. General morbidity was 52%, with an incidence of pancreatic fistulas of 36.8%, out of which only 26% were grade B and C fistulas according to the classification proposed by Bassi et al.8

Immunohistochemistry studies of the insulinomas were able to better characterize these neoplasms. It was interesting to observe that those insulinomas with liver metastases had a Ki-67>2%.

The histology results to define NIPHS show the presence of pancreatic islets of different sizes, characterized by an accumulation of neuroendocrine cells within the acinar parenchyma, habitually in contact with small or large ducts (duct-islet complexes). The low incidence of this pathology requires trained pathologists who are familiarized with the study of pancreatic diseases.

Due to the morphological and functional characteristics of this type of tumors, the diagnosis, localization and treatment of these patients can often be demanding. Multidisciplinary management (surgeons, interventional radiologists and endocrinologists) is essential for the best possible results in this type of patients.

Conflict of InterestsNone of the authors received economic support for writing this paper.

Please cite this article as: de Santibañes M, Cristiano A, Mazza O, Grossenbacher L, de Santibañes E, Sánchez Clariá R, et al. Síndrome de hipoglucemia por hiperinsulinismo endógeno: tratamiento quirúrgico. Cir Esp. 2014;92:547–552.