Sleeve gastrectomy is a safe and effective bariatric surgery in terms of weight loss and longterm improvement or resolution of comorbidities. However, its achilles heel is the possible association with the development with the novo and/or worsening of pre-existing gastroesophageal reflux disease. The anatomical and mechanical changes that this technique induces in the esophagogastric junction, support or contradict this hypothesis. Questions such as «what is the natural history of gastroesophageal reflux in the patient undergoing gastric sleeve surgery?», «how many patients after vertical gastrectomy will develop gastroesophageal reflux?» and «how many patients will worsen their previous reflux after this technique?» are intended to be addressed in the present article.

La gastrectomía vertical es una técnica segura y eficaz que ha demostrado excelentes resultados en relación con la pérdida ponderal y la resolución o mejoría de las comorbilidades más comunes asociadas a la obesidad a largo plazo. Sin embargo, una de las mayores preocupaciones entorno a ella es su presumible condición reflujogénica, no del todo tipificada. Cuestiones como «¿cuál es la historia natural del reflujo gastroesofágico (RGE) en el paciente intervenido de un sleeve gástrico?», «¿cuántos pacientes tras una GV desarrollarán RGE?» y «¿cuántos pacientes empeoraran su reflujo previo tras la realización de esta técnica?» pretenden ser abordadas en el presente artículo. Se ha realizado una revisión sistemática siguiendo las recomendaciones PRISMA, utilizando diversas bases de datos, para intentar dar una respuesta a las anteriores preguntas.

Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) is the most commonly performed bariatric surgical procedure around the world.1–3 It has been consolidated as a primary technique due to its safety and efficacy for weight loss as well as for improving or resolving comorbidities associated with obesity in the long term.4–9 However, its Achilles’ heel is its possible association with the development of de novo gastroesophageal reflux or the worsening of persistent reflux. The modified pathophysiological and anatomical mechanisms that are a result of this technique both support and contradict this theory.

Two types of factors have been described as the main causes of the appearance of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) after SG: those originating from the anatomical modifications entailed in the surgical technique, and those caused by mechanical complications. The reduced gastric volume, complete resection of the fundus, and dissection of the fibers of the esophagogastric junction which compromise the efficiency of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) could increase exposure of the esophagus to acid.10 In addition, mechanical postoperative complications, such as stenosis or torsion of the gastric tube,11 would be linked to the appearance of reflux-related symptoms.

At the same time, obesity is one of the main independent risk factors for the development of GER. Being overweight increases pathological reflux from 1.2 to 3-fold, and its prevalence in obese patients is 37%–72%. In addition, functional studies have demonstrated that for every increase of 5 kg/m2 in body mass index (BMI), the DeMeester reflux score also increases by 3 points. This correlation between GER and obesity can be explained by certain physiological changes induced by this pathology, such as increased intra-abdominal pressure, altered morphology of the gastroesophageal junction, presence of a dysfunctional LES, increased intragastric pressure, associated esophageal motility alterations, and the higher frequency of hiatal hernia. Thus, weight loss could result in improved GER symptoms.12–14

The actual extent of the impact that SG has on the development or evolution of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is unknown. The current scarcity of properly designed homogeneous studies that include endoscopic and functional evaluations (manometry, 24-h esophageal pH monitoring, impedance test, or gastric emptying scintigraphy) and correlate the findings of these tests with patient symptoms before and after surgery do not allow solid conclusions to be drawn and may even lead to contradictory results.

The intention of this article is to address certain questions, such as: What is the natural history of gastroesophageal reflux in patients treated with sleeve gastrectomy?, How many patients will develop gastroesophageal reflux after sleeve gastrectomy? and How many patients will experience worse reflux after undergoing this technique?

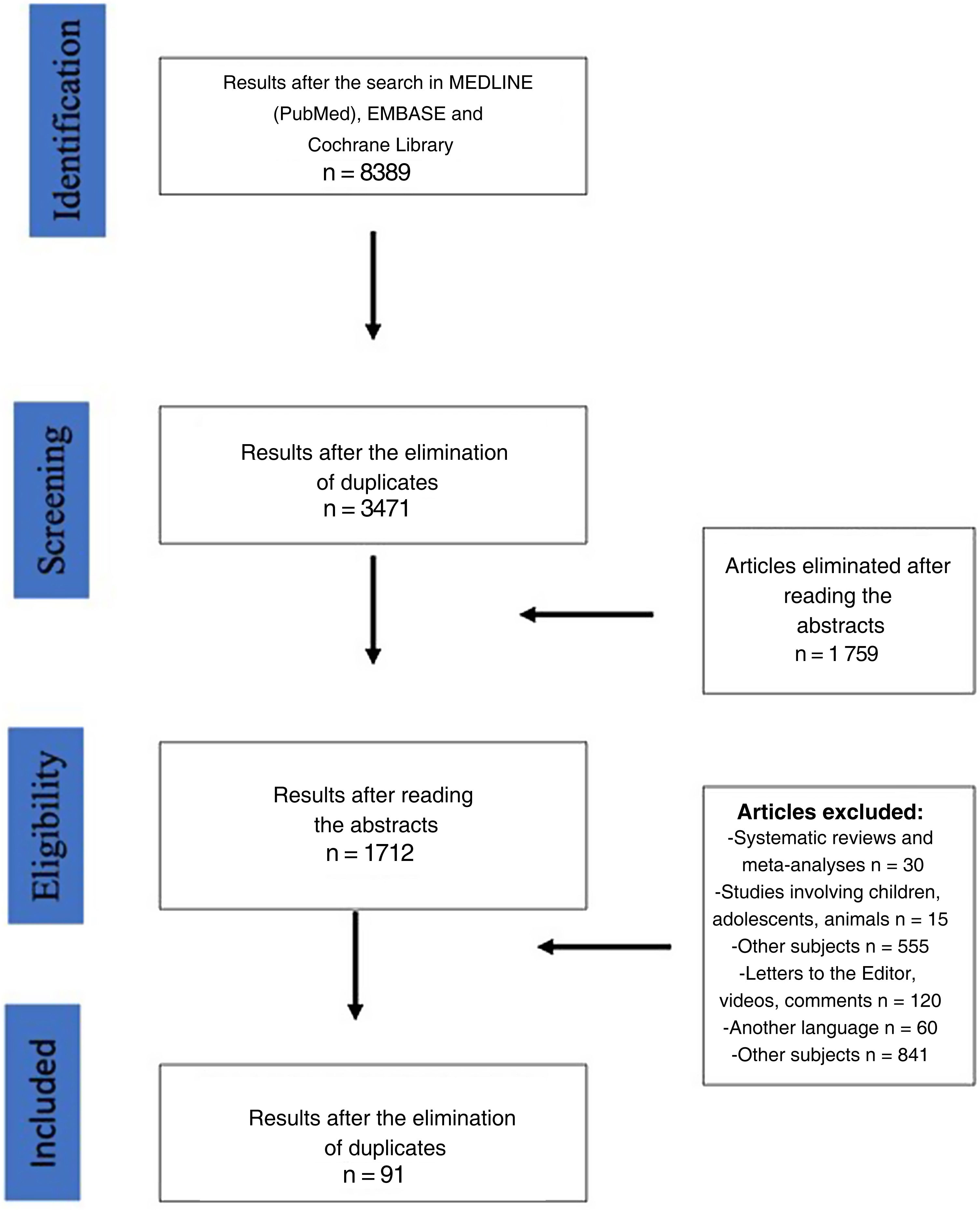

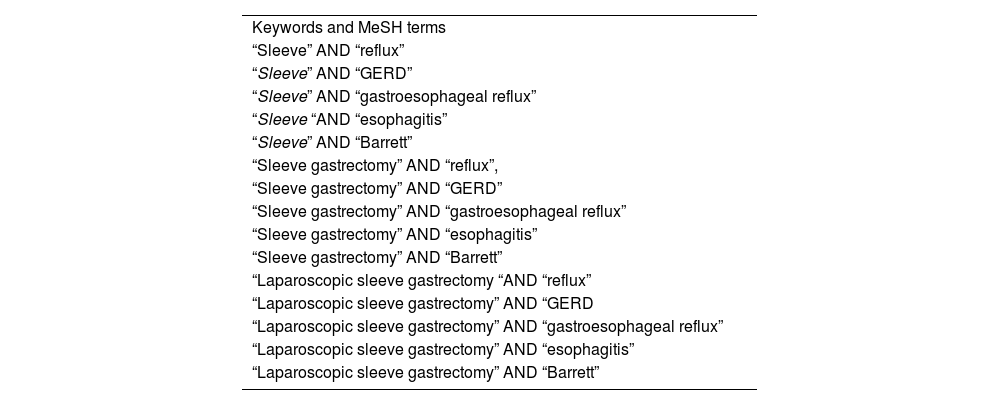

MethodsSearch strategyThe systematic review of the literature was performed following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement.15 Bibliographic searches of studies published up to September 2022 were carried out in the MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE and Cochrane Library databases, using certain keywords and MeSH terms (see Table 1). The search, selection, and subsequent analysis were carried out independently by 2 authors (SFA and EMT), and any differences between them were submitted for independent assessment by a third author (CBP).

Keywords and MeSH terms used in the search of the MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE and Cochrane Library databases.

| Keywords and MeSH terms |

| “Sleeve” AND “reflux” |

| “Sleeve” AND “GERD” |

| “Sleeve” AND “gastroesophageal reflux” |

| “Sleeve “AND “esophagitis” |

| “Sleeve” AND “Barrett” |

| “Sleeve gastrectomy” AND “reflux”, |

| “Sleeve gastrectomy” AND “GERD” |

| “Sleeve gastrectomy” AND “gastroesophageal reflux” |

| “Sleeve gastrectomy” AND “esophagitis” |

| “Sleeve gastrectomy” AND “Barrett” |

| “Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy “AND “reflux” |

| “Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy” AND “GERD |

| “Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy” AND “gastroesophageal reflux” |

| “Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy” AND “esophagitis” |

| “Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy” AND “Barrett” |

The data we extracted and analyzed from each article included the following: sample size, mean age, mean BMI, presence of reflux symptoms before and after surgery, endoscopic and functional tests (manometry, pH-metry) before and after bariatric surgery, need for proton pump inhibitors (PPI), technical factors of SG (Foucher tube size, distance between the first endostaple and the pylorus) and follow-up time (months).

The approval of the Ethics Committee of our institution and informed consent of the patients were not necessary to conduct this systematic review.

Study objectivesThe primary objective of the study was to determine the incidence of reflux, esophagitis, and the development of Barrett’s esophagus after sleeve gastrectomy. As secondary objectives, we analyzed those articles that documented the diagnosis of GER prior to SG, the percentage of patients who presented worse symptoms after SG, the possible correlation with technical variations, and quality-of-life studies.

Eligibility criteriaThe inclusion criteria of the articles were the following: 1) Articles that analyze the relationship between SG and GER; 2) Both single-center and multicenter studies; 3) Publications with more than 50 patients; 4) Papers that did not meet any of the exclusion criteria.

The following were considered exclusion criteria: 1) Case reports or videos; 2) Editorials, article commentary, or Letters to the Editor; 3) Studies with fewer than 50 patients; 4) Systematic reviews and meta-analyses; 5) Articles written in a language other than English; 6) Studies involving children, adolescents or animals; 7) Studies comparing SG with another bariatric surgery technique; 8) Studies combining SG with other techniques that involve the hiatus or the esophagogastric junction (cruroplasty, fundoplications).

In the event that the same author or group had published more than one article based on the same series, the most recent publication was included in the analysis, and the remainder was rejected.

Studies that evaluated data related to GER symptoms, endoscopic explorations, and pre- and postoperative functional tests (as well as their evolution) are referred to as the complete group. The remaining studies were classified as the incomplete group.

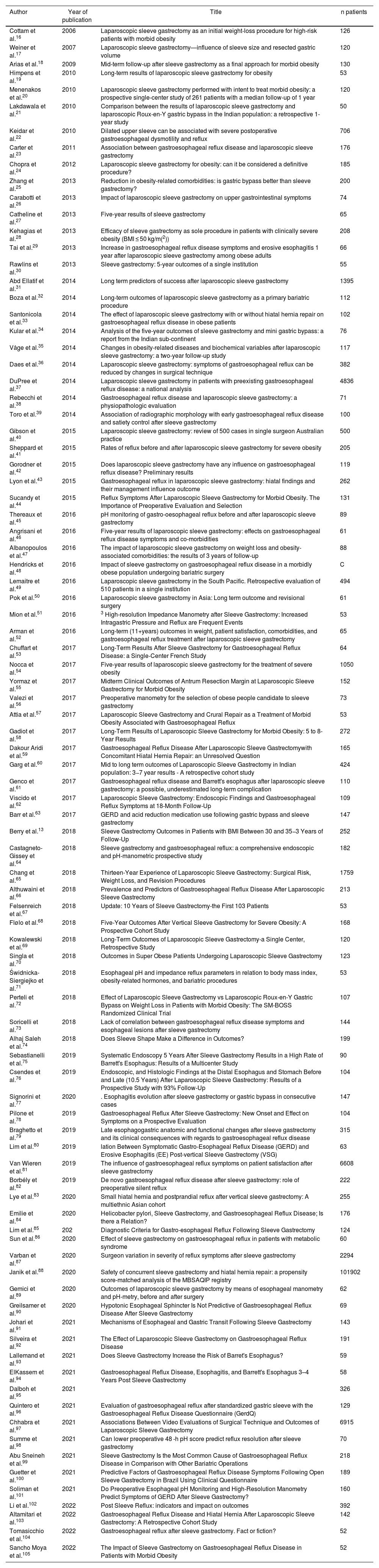

ResultsThe search of the literature identified a total of 8389 articles. After eliminating duplicate articles and those that presented exclusion criteria, 91 papers were finally included in the study (Fig. 1) (Table 2). Following the criteria defined in the Materials section, 7 papers were considered complete.

Reference of the 91 articles reviewed.

| Author | Year of publication | Title | n patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cottam et al.16 | 2006 | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as an initial weight-loss procedure for high-risk patients with morbid obesity | 126 |

| Weiner et al.17 | 2007 | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy—influence of sleeve size and resected gastric volume | 120 |

| Arias et al.18 | 2009 | Mid-term follow-up after sleeve gastrectomy as a final approach for morbid obesity | 130 |

| Himpens et al.19 | 2010 | Long-term results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for obesity | 53 |

| Menenakos et al.20 | 2010 | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy performed with intent to treat morbid obesity: a prospective single-center study of 261 patients with a median follow-up of 1 year | 120 |

| Lakdawala et al.21 | 2010 | Comparison between the results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in the Indian population: a retrospective 1-year study | 50 |

| Keidar et al.22 | 2010 | Dilated upper sleeve can be associated with severe postoperative gastroesophageal dysmotility and reflux | 706 |

| Carter et al.23 | 2011 | Association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | 176 |

| Chopra et al.24 | 2012 | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for obesity: can it be considered a definitive procedure? | 185 |

| Zhang et al.25 | 2013 | Reduction in obesity-related comorbidities: is gastric bypass better than sleeve gastrectomy? | 200 |

| Carabotti et al.26 | 2013 | Impact of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on upper gastrointestinal symptoms | 74 |

| Catheline et al.27 | 2013 | Five-year results of sleeve gastrectomy | 65 |

| Kehagias et al.28 | 2013 | Efficacy of sleeve gastrectomy as sole procedure in patients with clinically severe obesity (BMI ≤ 50 kg/m(2)) | 208 |

| Tai et al.29 | 2013 | Increase in gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms and erosive esophagitis 1 year after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy among obese adults | 66 |

| Rawlins et al.30 | 2013 | Sleeve gastrectomy: 5-year outcomes of a single institution | 55 |

| Abd Ellatif et al.31 | 2014 | Long term predictors of success after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | 1395 |

| Boza et al.32 | 2014 | Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as a primary bariatric procedure | 112 |

| Santonicola et al.33 | 2014 | The effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy with or without hiatal hernia repair on gastroesophageal reflux disease in obese patients | 102 |

| Kular et al.34 | 2014 | Analysis of the five-year outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy and mini gastric bypass: a report from the Indian sub-continent | 76 |

| Våge et al.35 | 2014 | Changes in obesity-related diseases and biochemical variables after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a two-year follow-up study | 117 |

| Daes et al.36 | 2014 | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux can be reduced by changes in surgical technique | 382 |

| DuPree et al.37 | 2014 | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in patients with preexisting gastroesophageal reflux disease: a national analysis | 4836 |

| Rebecchi et al.38 | 2014 | Gastroesophageal reflux disease and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a physiopathologic evaluation | 71 |

| Toro et al.39 | 2014 | Association of radiographic morphology with early gastroesophageal reflux disease and satiety control after sleeve gastrectomy | 100 |

| Gibson et al.40 | 2015 | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: review of 500 cases in single surgeon Australian practice | 500 |

| Sheppard et al.41 | 2015 | Rates of reflux before and after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for severe obesity | 205 |

| Gorodner et al.42 | 2015 | Does laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy have any influence on gastroesophageal reflux disease? Preliminary results | 119 |

| Lyon et al.43 | 2015 | Gastroesophageal reflux in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: hiatal findings and their management influence outcome | 262 |

| Sucandy et al.44 | 2015 | Reflux Symptoms After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy for Morbid Obesity. The Importance of Preoperative Evaluation and Selection | 131 |

| Thereaux et al.45 | 2016 | pH monitoring of gastro-oesophageal reflux before and after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | 89 |

| Angrisani et al.46 | 2016 | Five-year results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: effects on gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms and co-morbidities | 61 |

| Albanopoulos et al.47 | 2016 | The impact of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on weight loss and obesity-associated comorbidities: the results of 3 years of follow-up | 88 |

| Hendricks et al.48 | 2016 | Impact of sleeve gastrectomy on gastroesophageal reflux disease in a morbidly obese population undergoing bariatric surgery | C |

| Lemaitre et al.49 | 2016 | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in the South Pacific. Retrospective evaluation of 510 patients in a single institution | 494 |

| Pok et al.50 | 2016 | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in Asia: Long term outcome and revisional surgery | 61 |

| Mion et al.51 | 2016 | 3 High-resolution Impedance Manometry after Sleeve Gastrectomy: Increased Intragastric Pressure and Reflux are Frequent Events | 53 |

| Arman et al.52 | 2016 | Long-term (11+years) outcomes in weight, patient satisfaction, comorbidities, and gastroesophageal reflux treatment after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | 65 |

| Chuffart et al.53 | 2017 | Long-Term Results After Sleeve Gastrectomy for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: a Single-Center French Study | 64 |

| Nocca et al.54 | 2017 | Five-year results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for the treatment of severe obesity | 1050 |

| Yormaz et al.55 | 2017 | Midterm Clinical Outcomes of Antrum Resection Margin at Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy for Morbid Obesity | 152 |

| Valezi et al.56 | 2017 | Preoperative manometry for the selection of obese people candidate to sleeve gastrectomy | 73 |

| Attia et al.57 | 2017 | Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy and Crural Repair as a Treatment of Morbid Obesity Associated with Gastroesophageal Reflux | 53 |

| Gadiot et al.58 | 2017 | Long-Term Results of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy for Morbid Obesity: 5 to 8-Year Results | 272 |

| Dakour Aridi et al.59 | 2017 | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomywith Concomitant Hiatal Hernia Repair: an Unresolved Question | 165 |

| Garg et al.60 | 2017 | Mid to long term outcomes of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy in Indian population: 3−7 year results - A retrospective cohort study | 424 |

| Genco et al.61 | 2017 | Gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett's esophagus after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a possible, underestimated long-term complication | 110 |

| Viscido et al.62 | 2017 | Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: Endoscopic Findings and Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptoms at 18-Month Follow-Up | 109 |

| Barr et al.63 | 2017 | GERD and acid reduction medication use following gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy | 147 |

| Berry et al.13 | 2018 | Sleeve Gastrectomy Outcomes in Patients with BMI Between 30 and 35−3 Years of Follow-Up | 252 |

| Castagneto-Gissey et al.64 | 2018 | Sleeve gastrectomy and gastroesophageal reflux: a comprehensive endoscopic and pH-manometric prospective study | 182 |

| Chang et al.65 | 2018 | Thirteen-Year Experience of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: Surgical Risk, Weight Loss, and Revision Procedures | 1759 |

| Althuwaini et al.66 | 2018 | Prevalence and Predictors of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy | 213 |

| Felsenreich et al.67 | 2018 | Update: 10 Years of Sleeve Gastrectomy-the First 103 Patients | 53 |

| Flølo et al.68 | 2018 | Five-Year Outcomes After Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy for Severe Obesity: A Prospective Cohort Study | 168 |

| Kowalewski et al.69 | 2018 | Long-Term Outcomes of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy-a Single Center, Retrospective Study | 120 |

| Singla et al.70 | 2018 | Outcomes in Super Obese Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy | 123 |

| Świdnicka-Siergiejko et al.71 | 2018 | Esophageal pH and impedance reflux parameters in relation to body mass index, obesity-related hormones, and bariatric procedures | 53 |

| Perteli et al.72 | 2018 | Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy vs Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Weight Loss in Patients with Morbid Obesity: The SM-BOSS Randomized Clinical Trial | 107 |

| Soricelli et al.73 | 2018 | Lack of correlation between gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms and esophageal lesions after sleeve gastrectomy | 144 |

| Alhaj Saleh et al.74 | 2018 | Does Sleeve Shape Make a Difference in Outcomes? | 199 |

| Sebastianelli et al.75 | 2019 | Systematic Endoscopy 5 Years After Sleeve Gastrectomy Results in a High Rate of Barrett's Esophagus: Results of a Multicenter Study | 90 |

| Csendes et al.76 | 2019 | Endoscopic, and Histologic Findings at the Distal Esophagus and Stomach Before and Late (10.5 Years) After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: Results of a Prospective Study with 93% Follow-Up | 104 |

| Signorini et al.77 | 2020 | . Esophagitis evolution after sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass in consecutive cases | 147 |

| Pilone et al.78 | 2019 | Gastroesophageal Reflux After Sleeve Gastrectomy: New Onset and Effect on Symptoms on a Prospective Evaluation | 104 |

| Braghetto et al.79 | 2019 | Late esophagogastric anatomic and functional changes after sleeve gastrectomy and its clinical consequences with regards to gastroesophageal reflux disease | 315 |

| Lim et al.80 | 2019 | lation Between Symptomatic Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) and Erosive Esophagitis (EE) Post-vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy (VSG) | 63 |

| Van Wieren et al.81 | 2019 | The influence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms on patient satisfaction after sleeve gastrectomy | 6608 |

| Borbély et al.82 | 2019 | De novo gastroesophageal reflux disease after sleeve gastrectomy: role of preoperative silent reflux | 222 |

| Lye et al.83 | 2020 | Small hiatal hernia and postprandial reflux after vertical sleeve gastrectomy: A multiethnic Asian cohort | 255 |

| Emilie et al.84 | 2020 | Helicobacter pylori, Sleeve Gastrectomy, and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease; Is there a Relation? | 176 |

| Lim et al.85 | 202 | Diagnostic Criteria for Gastro-esophageal Reflux Following Sleeve Gastrectomy | 124 |

| Sun et al.86 | 2020 | Effect of sleeve gastrectomy on gastroesophageal reflux in patients with metabolic syndrome | 60 |

| Varban et al.87 | 2020 | Surgeon variation in severity of reflux symptoms after sleeve gastrectomy | 2294 |

| Janik et al.88 | 2020 | Safety of concurrent sleeve gastrectomy and hiatal hernia repair: a propensity score-matched analysis of the MBSAQIP registry | 101902 |

| Gemici et al.89 | 2020 | Outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy by means of esophageal manometry and pH-metry, before and after surgery | 62 |

| Greilsamer et al.90 | 2020 | Hypotonic Esophageal Sphincter Is Not Predictive of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease After Sleeve Gastrectomy | 69 |

| Johari et al.91 | 2021 | Mechanisms of Esophageal and Gastric Transit Following Sleeve Gastrectomy | 143 |

| Silveira et al.92 | 2021 | The Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease | 191 |

| Lallemand et al.93 | 2021 | Does Sleeve Gastrectomy Increase the Risk of Barret's Esophagus? | 59 |

| ElKassem et al.94 | 2021 | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, Esophagitis, and Barrett's Esophagus 3–4 Years Post Sleeve Gastrectomy | 58 |

| Dalboh et al.95 | 2021 | 326 | |

| Quintero et al.96 | 2021 | Evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux after standardized gastric sleeve with the Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Questionnaire (GerdQ) | 129 |

| Chhabra et al.97 | 2021 | Associations Between Video Evaluations of Surgical Technique and Outcomes of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy | 6915 |

| Summe et al.98 | 2021 | Can lower preoperative 48 -h pH score predict reflux resolution after sleeve gastrectomy | 70 |

| Abu Sneineh et al.99 | 2021 | Sleeve Gastrectomy Is the Most Common Cause of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Comparison with Other Bariatric Operations | 218 |

| Guetter et al.100 | 2021 | Predictive Factors of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Symptoms Following Open Sleeve Gastrectomy in Brazil Using Clinical Questionnaire | 189 |

| Soliman et al.101 | 2021 | Do Preoperative Esophageal pH Monitoring and High-Resolution Manometry Predict Symptoms of GERD After Sleeve Gastrectomy? | 160 |

| Li et al.102 | 2022 | Post Sleeve Reflux: indicators and impact on outcomes | 392 |

| Altamitari et al.103 | 2022 | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Hiatal Hernia After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: A Retrospective Cohort Study | 142 |

| Tomasicchio et al.104 | 2022 | Gastroesophageal reflux after sleeve gastrectomy. Fact or fiction? | 52 |

| Sancho Moya et al.105 | 2022 | The Impact of Sleeve Gastrectomy on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Patients with Morbid Obesity | 52 |

The total number of patients analyzed was 140 387, with a mean age of 41.64 ± 3.67 years and a BMI of 44.4 ± 6.49 (R 32.3–60.7). The mean follow-up time was 39.67 ± 34.58 months (R 1–147), and this datum was reported in 93.4% (n = 85) of the articles.

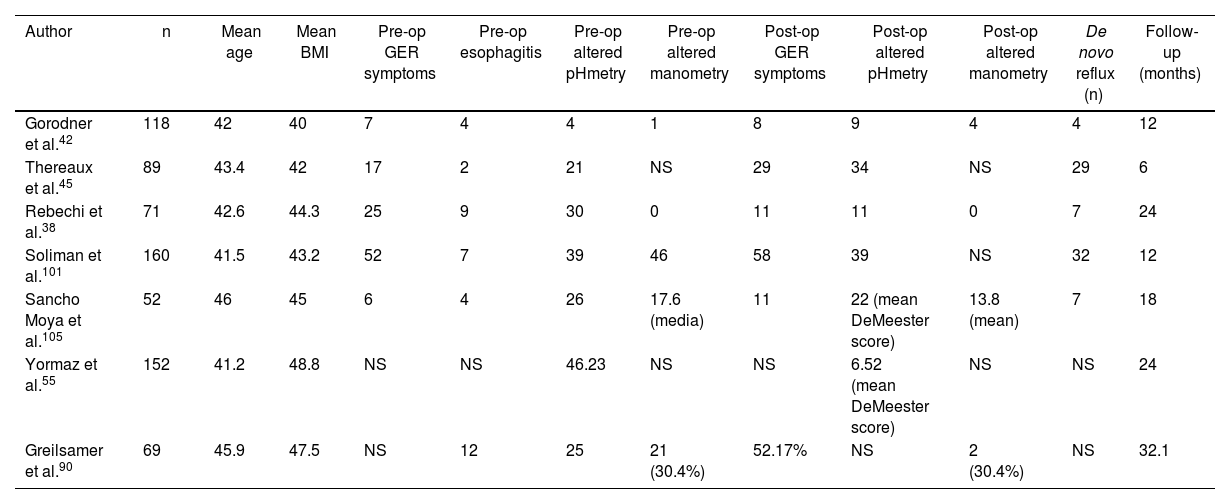

Complete group resultsThe 7 articles that were defined as complete38,42,45,55,90,101,105 included a total of 711 patients. Mean age was 43.22 years (SD 2.82), mean BMI was 44.4 (SD 2.51), and mean follow-up time was 18.3 months (R 6–32.1). Among these 7 articles, 538,42,45,101,105 reported and correlated clinical and functional data before as well as after sleeve gastrectomy. Out of these 490 patients, 107 presented preoperative symptoms of esophagogastric reflux, 26 of whom presented esophagitis (grade A n = 10 and grade C n = 1; in the remainder, unspecified) on preoperative endoscopy. Prior to surgery, 24-h pH monitoring found an altered DeMeester score (>14.3) in 83 patients, and manometry detected decreased lower esophageal sphincter pressure in 47 patients. After a mean follow-up of 18.3 months (R 6–32.1), 16.1% (n = 79) of patients developed de novo reflux. In total, 107 patients had preoperative reflux symptoms, and 117 presented postoperative reflux, which is an increase of 1% after sleeve gastrectomy over the total number of patients (n = 711) (see Table 3).

Articles included in the “complete group”.

| Author | n | Mean age | Mean BMI | Pre-op GER symptoms | Pre-op esophagitis | Pre-op altered pHmetry | Pre-op altered manometry | Post-op GER symptoms | Post-op altered pHmetry | Post-op altered manometry | De novo reflux (n) | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gorodner et al.42 | 118 | 42 | 40 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

| Thereaux et al.45 | 89 | 43.4 | 42 | 17 | 2 | 21 | NS | 29 | 34 | NS | 29 | 6 |

| Rebechi et al.38 | 71 | 42.6 | 44.3 | 25 | 9 | 30 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 7 | 24 |

| Soliman et al.101 | 160 | 41.5 | 43.2 | 52 | 7 | 39 | 46 | 58 | 39 | NS | 32 | 12 |

| Sancho Moya et al.105 | 52 | 46 | 45 | 6 | 4 | 26 | 17.6 (media) | 11 | 22 (mean DeMeester score) | 13.8 (mean) | 7 | 18 |

| Yormaz et al.55 | 152 | 41.2 | 48.8 | NS | NS | 46.23 | NS | NS | 6.52 (mean DeMeester score) | NS | NS | 24 |

| Greilsamer et al.90 | 69 | 45.9 | 47.5 | NS | 12 | 25 | 21 (30.4%) | 52.17% | NS | 2 (30.4%) | NS | 32.1 |

Only 20 articles (21.7% of the studies studied) (n = 10 360) provided the number of patients affected by de novo reflux after SG (n = 823; 7.9%). The mean follow-up time of these patients was 46.51 months (R 6–126).13,22,24,29,30,32,33,37,42,48,50,59,60,64,65,69,70,76,83,105

Fifty-five articles (60.43%) reported GER symptoms before and after surgery. In 30, improved symptoms were observed, while 25 reported worse symptoms. One-third (33.33%; n = 106) of the patients included in the study had reported GER-related symptoms before surgery, and 16.66% had used proton pump inhibitor (PPI) drugs as part of their usual medication for control. Only 20 (21.73%) of the 91 articles specified this datum. After SG, the percentage of GER symptoms was 25.76% (SD 23.61).

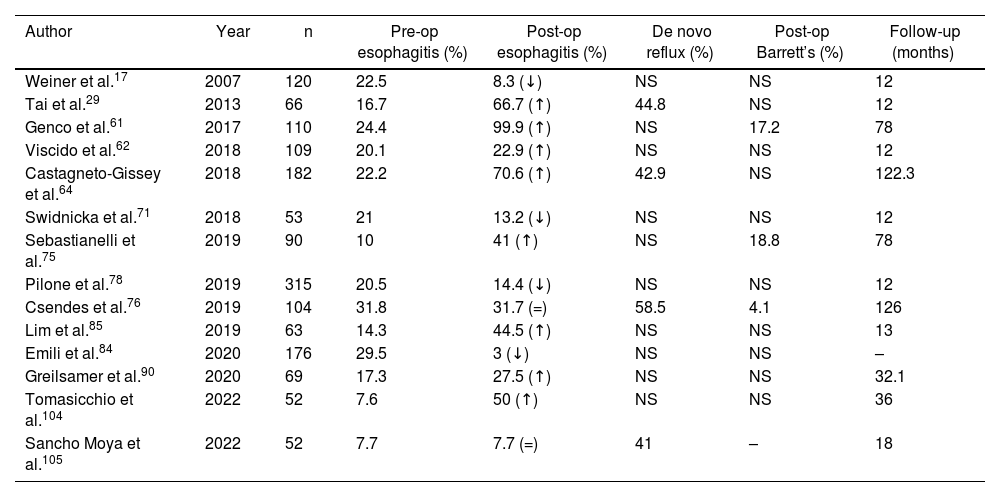

The diagnosis of esophagitis was made by endoscopy in 361 patients prior to performing SG. Out of the 91 articles analyzed, 20 (n = 2006 patients) included this datum. The postoperative diagnosis of esophagitis was reported in 19 articles (n = 2312), affecting 427 (18.4%) patients. Only 14 articles (n = 1350) included both pre- and postoperative diagnoses of esophagitis, showing an increase of 58% (pre-op esophagitis n = 186; post-op esophagitis n = 318) (Table 4).

Evolution of the diagnosis of esophagitis in the articles analyzed.

| Author | Year | n | Pre-op esophagitis (%) | Post-op esophagitis (%) | De novo reflux (%) | Post-op Barrett’s (%) | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weiner et al.17 | 2007 | 120 | 22.5 | 8.3 (↓) | NS | NS | 12 |

| Tai et al.29 | 2013 | 66 | 16.7 | 66.7 (↑) | 44.8 | NS | 12 |

| Genco et al.61 | 2017 | 110 | 24.4 | 99.9 (↑) | NS | 17.2 | 78 |

| Viscido et al.62 | 2018 | 109 | 20.1 | 22.9 (↑) | NS | NS | 12 |

| Castagneto-Gissey et al.64 | 2018 | 182 | 22.2 | 70.6 (↑) | 42.9 | NS | 122.3 |

| Swidnicka et al.71 | 2018 | 53 | 21 | 13.2 (↓) | NS | NS | 12 |

| Sebastianelli et al.75 | 2019 | 90 | 10 | 41 (↑) | NS | 18.8 | 78 |

| Pilone et al.78 | 2019 | 315 | 20.5 | 14.4 (↓) | NS | NS | 12 |

| Csendes et al.76 | 2019 | 104 | 31.8 | 31.7 (=) | 58.5 | 4.1 | 126 |

| Lim et al.85 | 2019 | 63 | 14.3 | 44.5 (↑) | NS | NS | 13 |

| Emili et al.84 | 2020 | 176 | 29.5 | 3 (↓) | NS | NS | – |

| Greilsamer et al.90 | 2020 | 69 | 17.3 | 27.5 (↑) | NS | NS | 32.1 |

| Tomasicchio et al.104 | 2022 | 52 | 7.6 | 50 (↑) | NS | NS | 36 |

| Sancho Moya et al.105 | 2022 | 52 | 7.7 | 7.7 (=) | 41 | – | 18 |

ns not specified in the article; ↓ decrease in the percentage of patients with esophagitis after surgery; ↑ increase in the percentage of patients with esophagitis after surgery; = same percentage of patients diagnosed with esophagitis before and after surgery.

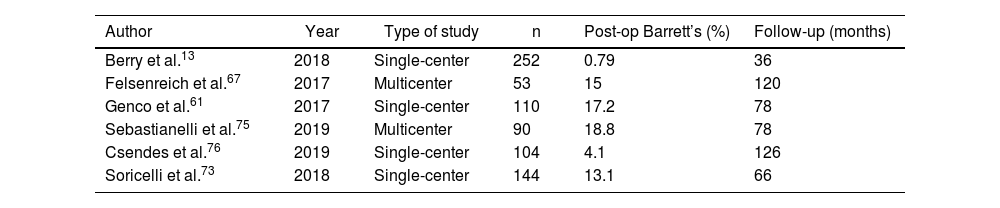

The development of Barrett’s esophagus was only reported by 6 articles.13,61,67,73,75,76 Out of a total of 590 patients among them, 74 (12.54%) were diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus by postoperative endoscopy. Mean follow-up was 84 months (R 36–126) (Table 5).

Development of Barrett’s esophagus in the articles analyzed.

| Author | Year | Type of study | n | Post-op Barrett’s (%) | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berry et al.13 | 2018 | Single-center | 252 | 0.79 | 36 |

| Felsenreich et al.67 | 2017 | Multicenter | 53 | 15 | 120 |

| Genco et al.61 | 2017 | Single-center | 110 | 17.2 | 78 |

| Sebastianelli et al.75 | 2019 | Multicenter | 90 | 18.8 | 78 |

| Csendes et al.76 | 2019 | Single-center | 104 | 4.1 | 126 |

| Soricelli et al.73 | 2018 | Single-center | 144 | 13.1 | 66 |

Data were collected for variables related to the surgical technique, such as the caliber of the bougie used and the distance between the pylorus and the first endostaple (EndoGIA). The most used Foucher catheter size was 36 French (Fr) in 40.67% of the articles, followed by 32 Fr (16.94%) and 38 Fr (8.47%). The calibers used to shape the sleeve ranged from 26.4 Fr (endoscope) (30) to 50 Fr. However, 32 articles (35.16%) did not indicate the type of catheter used.

Regarding the placement of the first EndoGIA staple, 41 (44.56%) articles provided this information: in 10 (24.39%), it was placed less than 4 cm from the pylorus (R 1–3); and in 31 (75.60%), it was placed ≥4 cm away (R 4–6).

No statistically significant relationship was found between either of the 2 characteristics related to the surgical technique and the appearance of de novo reflux.

Only 22 of the 91 articles reviewed included a quality-of-life questionnaire as part of the follow-up. Furthermore, different scales were used among them (SF-36, GERD-SS, GIQLY, VAS, RDQ, Visick, RSI, GSAS GERD, Likert) so it is not possible to make adequate comparisons.17,19,38,43,52,55,63,66–68,72,78,81,84,86,87,92,95–97,99,100

DiscussionObesity is one of the main risk factors for the development of GER and Barrett’s esophagus. Being overweight has been shown to increases pathological reflux between 1.2 and 3-fold, and its prevalence in obese patients ranges from 37% to 72%. In addition, pH monitoring studies have reported that each increment of 5 kg/m2 in BMI is associated with an increase of 3 points on the DeMeester scale. This connection is explained by physiological changes derived from obesity, including higher intra-abdominal pressure, altered gastroesophageal junction morphology, dysfunctional LES, greater intragastric pressure, associated esophageal motility alterations, and the higher incidence of hiatal hernia. SG theoretically alters all the natural anti-reflux mechanisms, which would favor the appearance of its symptoms. It modifies the angle of His due to the dissection of this area to create the gastric sleeve and, in some cases, it also changes the configuration of the phrenoesophageal membrane, at least partially; it reduces LES pressure, probably due to resection of some of its oblique muscle fibers; it increases intragastric pressure by reducing the volume of the stomach, added to the presence of an intact pylorus; and it also alters gastric emptying when part of the antrum is resected. Nevertheless, we know that weight loss mitigates reflux symptoms, and several publications mention that SG could protect the gastroesophageal barrier by inducing rapid gastric emptying and reducing the population of parietal cells by removing the gastric fundus.12,13

Furthermore, it seems that the morphology of the remaining stomach has an important effect, not only on the induction of satiety, but also on the presentation of reflux symptoms. An inadequate surgical technique with a prominent fundus translates into greater GER symptoms and less control of satiety.14

The data that the current literature provides about the SG-GERD binomial are disparate. Some studies support the benefits of SG on reflux symptoms, while others disapprove of the technique.35

De novo reflux is defined as the presence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux, silent reflux, or functional esophageal disorder in patients who did not have reflux prior to surgery. The appearance of de novo reflux or the worsening of pre-existing reflux, resulting in deteriorated quality of life and the need for daily antacids, is a major concern and one of the most frequent causes of conversion from SG to gastric bypass.106

The rates of de novo reflux reported in the literature range from 0% to 69%,10,19 and from 0% to 93% in this current study. Logically, this wide range of percentages does not allow us to draw clear conclusions.

In order to delimit these wide margins and try to define the natural history of reflux in patients treated with sleeve gastrectomy, the idea for this study was born.

Initially, we have observed that, although several published studies address the SG-GER relationship, only a very small percentage (which we have called the complete group) include the set of variables that allow us to be more precise.

Only 7 papers studied clinical data and endoscopic and functional findings before and after surgery. Thus, with the most complete information possible, the percentage of de novo reflux after SG is 16%, while worsened symptoms was reported in 1% of patients with pre-existing reflux 14 months after surgery.

Moreover, it is important to highlight that only 20 of the 91 articles examined in this review mention the prevalence of this late complication, and a very limited number study its time of onset, with a mean postoperative follow-up of just over one year.

Along these lines, another of the most worrying dilemmas, especially in young patients, is the possible increase in Barrett’s esophagus with its consequent risk of developing esophageal cancer.107 But again, the scientific evidence related to this problem is scarce and heterogeneous. Only 6 articles provide this data (see Table 5), so it is not possible to establish firm resolutions.

Likewise, when interpreting and analyzing the data, we have encountered various obstacles. One is the lack of uniformity in the method used to collect symptom-related data. Most studies diagnose GERD based on the symptoms reported by the patient, and few use questionnaires and functional tests (24-h pH-metry and impedance pH-metry) or define the clinical phenotypes (symptomatic, silent, functional esophageal disorder, absence of GER)105,108,109 based on the main consensus documents.110–112

Another limitation is the lack of homogeneity or standardization in the complementary examinations carried out in the various studies. Very few studies had evaluated endoscopic and functional results, both preoperative and postoperative.

It should be noted that the systematic use of endoscopy before performing SG is highly controversial, and we observed 2 different currents among the scientific societies: those that argue it should not be indicated in the absence of symptoms; and those that defend its systematic use because symptoms are poor predictors for underlying lesions, as endoscopic findings may not correlate with symptoms reported by patients.73,113,114 Specifically, ASMBS, SAGES, IFSO and ASGE recommend that the use of endoscopy should be individualized according to the symptoms reported, while EAES suggests that all patients should be studied with endoscopy before undergoing bariatric surgery, arguing that the absence of symptoms does not exclude the presence of silent GER.115

Despite being the most widely performed bariatric surgical procedure worldwide, there is still no standardized surgery available, and certain technical factors are performed differently by the different workgroups. Once again, these circumstances hinder data analysis. For instance, the varying sizes of the bougies used to calibrate the sleeve shape, or the distance to the pylorus of the first EngoGIA staple, may influence any subsequent increase in GER symptoms.49,55,116

The truth is that we still cannot definitively answer some questions already raised in previous studies:117–120Do patients undergoing SG surgery for Barrett’s esophagus have the same etiopathogenesis as the rest of the population?; Should systematic fibrogastroscopy be implemented before and after SG, even if patients do not report reflux symptoms? And if so, for how long?; Can we predict which patients will develop reflux after SG?; Should performing SG be an absolute contraindication in patients with reflux symptoms?; What are the effects of SG on gastroesophageal reflux?

All these questions should be the subject of future studies in order to better understand the pathophysiology of the stomach after SG.

FundingNo funding or grants have been obtained for this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Fernández-Ananín S, Balagué Ponz C, Sala L, Molera A, Ballester E, Gonzalo B, et al. Reflujo gastroesofágico tras gastrectomía vertical: la dimensión del problema. Cir Esp. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2023.05.009