Pelvic exenteration (PE) offers the best chance of cure for locally advanced primary or recurrent pelvic organ malignancies invading adjacent organs. The aims of this study were to analyze results for any pelvic exenteration that includes rectal resection and the analysis of results of fecal and urinary reconstruction.

MethodFrom January 2000 to April 2014, 111 PE with rectal resection for any pelvic cancer were analyzed retrospectively at two national tertiary referral centers.

ResultsThirty-six colorectal anastomosis were performed. Urologic reconstructions performed were 30 double barrelled wet colostomy (DBWC), 14 Bricker ileal conduit (BIC), and 2 ureterocutaneostomies. Postoperative complications occurred in 71 patients (64%). Six deaths (5.4%) occurred within 30 postoperative days. 5-Year overall survival following R0 resection was 62.6%; R1, 42.7%; R2: 24.2% (P=.018). The resection margin status was associated with overall survival, local recurrence and distant recurrence.

ConclusionPelvic exenterations for any cause need to be performed in referral centers and by specialized surgeons. Anastomosis after modified supralevator pelvic exenteration for ovarian cancer, is safe. DBWC can be considered a valid option for urologic reconstruction. The most important prognostic factor after pelvic exenteration for malignant pelvic tumors is the status of surgical margins.

La exenteración pélvica (EP) ofrece la mejor oportunidad de curación para neoplasias malignas primarias o recurrentes de órganos pélvicos localmente avanzadas con invasión de estructuras adyacentes. Los objetivos de este estudio fueron analizar los resultados de las exenteración pélvica por diferentes orígenes que incluyeron resección rectal y valorar los resultados de la reconstrucción fecal y urinaria.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo de una serie de 111 exenteraciones pélvicas con resección rectal para distintos tipos de cáncer pélvico realizadas entre enero de 2000 y abril de 2014 en dos centros de referencia terciarios nacionales.

ResultadosSe realizaron 36 anastomosis colorrectales. Las reconstrucciones urológicas realizadas fueron 30 colostomías húmedas en asa lateral (DBWC), 14 conductos ileales de Bricker (BIC) y 2 ureterocutaneostomías. Setenta y un pacientes (64%) presentaron complicaciones postoperatorias. Seis muertes (5,4%) ocurrieron dentro de los 30 días postoperatorios. La supervivencia global a 5 años después de resección R0 fue del 62,6%; R1, 42,7%; R2, 24,2% (P=0,018). La invasión del margen de resección se asoció con los peores índices de supervivencia global, recidiva local y recurrencia a distancia.

ConclusiónLas exenteraciones pélvicas por diferentes neoplasias deben realizarse en centros de referencia y por cirujanos especializados. La anastomosis después de la exenteración pélvica supraelevadora modificada para el cáncer de ovario, es segura. La DBWC puede considerarse una opción válida para la reconstrucción urológica. El factor pronóstico más importante después de la exenteración pélvica para los tumores pélvicos malignos es el estado de los márgenes quirúrgicos.

Pelvic exenteration (PE) offers the best chance of cure for locally advanced primary or recurrent pelvic organ malignancies invading adjacent organs.1

Depending on the sex of the patient, PE is defined as: anterior pelvic exenteration (APE) including removal of the bladder and distal ureters in addition to the resection of central gynecological pelvic organs on females or urological organs on males not including sigmoid-rectal resection; posterior pelvic exenteration (PPE) when the rectosigmoid is removed in addition to gynecological and urological organs but bladder resection is not included and total pelvic exenteration (TPE) when intestinal, gynecological and urological organs are removed. PPE can include the anal canal in the resection or preserve it (modified supralevator pelvic exenteration (MSPE)).2 Any of these techniques are very aggressive for the patient and technically demanding for the surgeon.

PE is more frequently indicated for recurrent than for primary disease. Recurrent cervical cancer is the most common disease treated with PE.3 Approximately 10% of primary rectal cancers present with tumor invasion into adjacent organs4 and 50% of recurrent rectal cancer are extraluminal.5

Whether the tumor is primary rectal cancer or local recurrence from rectal, gynecological or urological cancers, complete resection with clear pathological margins is one of the most important prognostic factors after PE for cancer.6–8 Different series have shown a twofold 5 year disease-free survival rate (from 30 to 60%) when comparing negative with positive margin patients.9

Once the resection has been completed, reconstruction of urinary and fecal tracts is the second important issue. Indicating bowel reconstruction after PE is a difficult decision for colorectal surgeons and performing a primary anastomosis can be difficult.

The aim of this study was to analyze results from surgery for any pelvic exenteration (PE) that includes rectal resection. Secondary aim was the analysis of results from fecal and urinary reconstruction techniques.

MethodsA retrospective review of a series of consecutive patients who underwent a PE with rectal resection for any pelvic cancer between 2000 and 2014 at two national tertiary referral centers, Bellvitge University Hospital (HUB) and Vall d’Hebron University Hospital (HUVH), in Barcelona has been performed. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

All patients were operated on by a specialist team of colorectal surgeons with support from urological, spinal orthopedic and plastic surgeons on a case-by-case basis. The number of surgeons involved in these operations was restricted in any of the specialties participating. Every treatment decision was discussed in a referral multidisciplinary team meeting. For all the patients included in the present series surgery had curative intention.

Surgical indication was established after confirming diagnosis with biopsy in primary tumors and for recurrent cases. However, some surgical indications for pelvic recurrences were based on a high level of suspicion after radiological findings.

Imaging and staging of tumors were performed by high-resolution magnetic resonance of the pelvis (MRI), computed tomography (CT) of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis and positron emission tomographic scan (PET).

Surgical treatment of pelvic recurrence was decided if pelvic lesions did not infiltrate vascular structures nor sacral nerve roots (S2 level or higher) and if negative margins were deemed to be achieved. The presence of resectable distal recurrence (hepatic or pulmonary) was not an exclusion criteria for exenteration.

Pelvic exenterations were classified as TPE, including removal of the bladder and distal ureters, the rectum and central pelvic organs or PPE, involving removal of the central organs together with the rectosigmoid, with or without (MSPE) the anal canal.7 Individualized approaches, such as sacrectomy were also recorded.10

A diverting stoma after colorectal anastomosis was performed at the discretion of the attending colorectal surgeon.

The choice of urinary reconstruction was made after discussion between the patient and the specialist urologist, colorectal surgeon and according to the intraoperative situation. Alternatively, either ureterocutaneostomy or conduits were constructed. Standard technique for conduits included an ureterileostomy also named Bricker ileal conduit (BIC)11 or a double barrelled wet colostomy (DBWC)12 where ureters are implanted into a lateral-end colostomy to form a ureterocolostomy.

Decisions on perineal reconstruction were based on the size of the residual defect. Small perineal defects were deemed to be primary closed. If a large pelvic inlet defect was predicted, closure was combined with an omentoplasty or a mesh. Large defects were managed by myocutaneous flaps performed by plastic surgeons.

Demographic and preoperative data including body mass index, age, cancer diagnosis, co-morbidities (smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and pulmonary disease), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score and preoperative laboratory data (hemoglobin, creatinine, and albumin) were collected for analysis. Any adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment was recorded. Clinical outcomes were abstracted from medical records.

Complications were graded according to Clavien–Dindo classification.13 Mortality and short term postoperative complications within the first 30 postoperative days (along all the duration of the hospital stay if longer than 30 days) were recorded and included septicemia, multiorgan failure, postoperative hemoperitoneum, anastomotic leak, perineal wound dehiscence, reoperation rates and causes. Anastomotic leak was diagnosed in case of fecal drainage from pelvic drains, abdominal wound or perineum and/or extravasation of contrast at the anastomotic site in CT. A urine leak was defined as the presence of creatinine rich effluent from abdominal drains or wound sites and/or evidence of contrast extravasation from the conduit or ureteric anastomosis identified on imaging.

Long term postoperative complications occurring after the first 30 postoperative days were also assessed and included. Enteroperineal fistulae, perineal or parastomal hernia and possible urological complications (stenosis or pyelonephritis) were analyzed with special interest.

Pathology reports including histology, lymph node status and margins status were ascertained. The pathological resection margin status was R0 (microscopically clear resection margins of at least 1mm); R1 (microscopically involved resection margin with tumor within 1mm of the resection margin); and R2 (macroscopically involved resection margin).

Overall survival (OS), local recurrence (LR) and distant recurrence (DR) at 3 and 5 years were calculated.

Quantitative data are presented as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range. Qualitative data are presented as absolute numbers and percentages. The comparative study was performed using the chi-square test for qualitative data and Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test for quantitative data. Prognostic factors for survival were assessed by univariate analysis of recorded variables by Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test. A multivariate Cox regression analysis was used to adjust the survival outcomes by type of tumor and margin resection status. All P values lower than .05 were considered significant. Software R 3.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used.

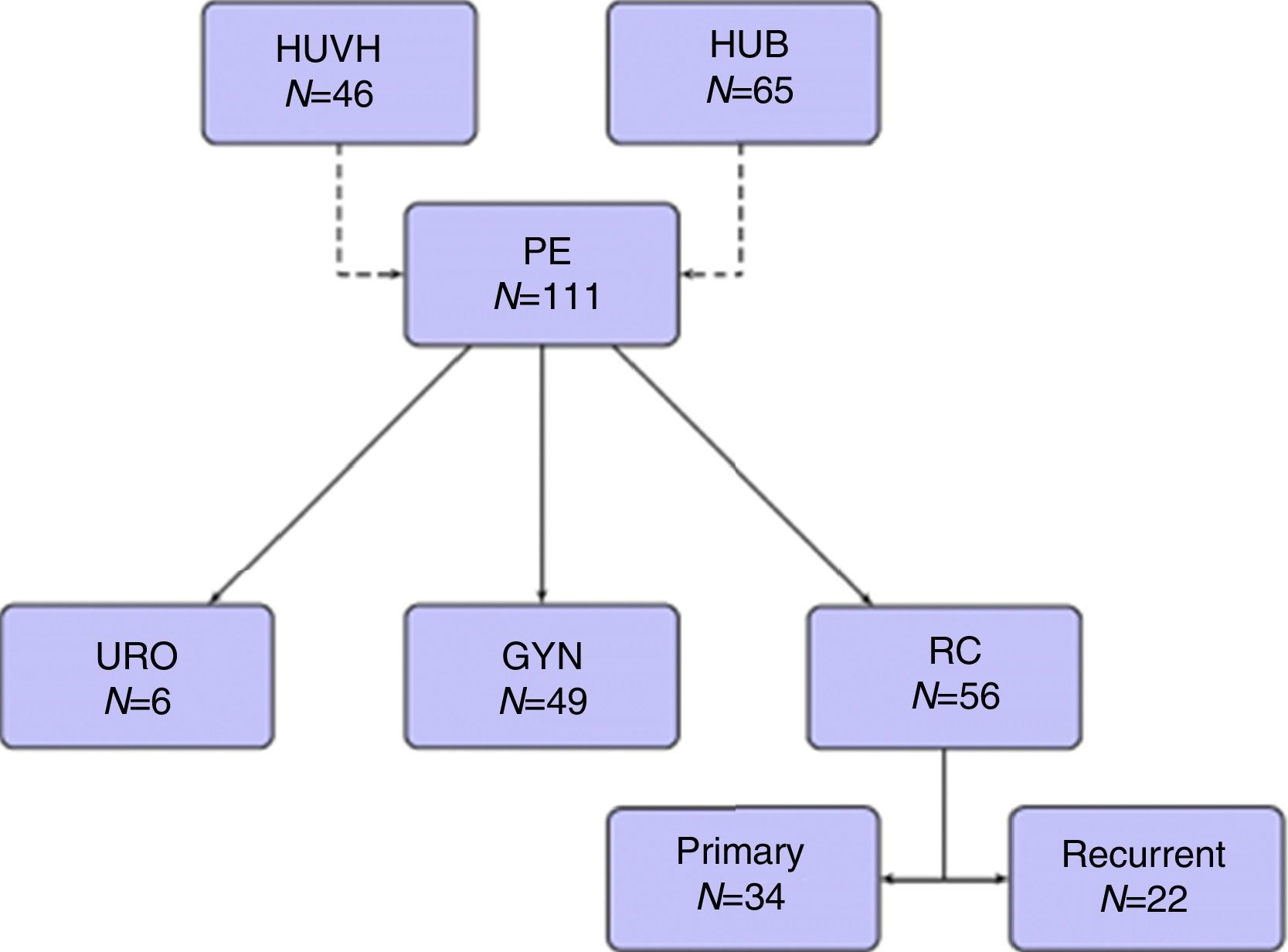

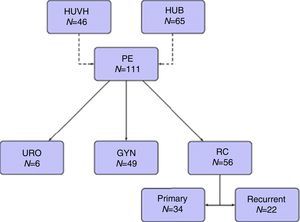

ResultsOne hundred and eleven patients were included during the study period, 65 from HUB and 46 from HUVH. Part of the patients from HUB with rectal cancer recurrence have been recently included in a previous publication.14

Forty-nine patients (44.1%) were operated on for gynecological tumors, 34 (30.6%) for primary rectal cancer, 22 (19.8%) for recurrent rectal cancer, and 6 (5.4%) for urological tumors (Fig. 1).

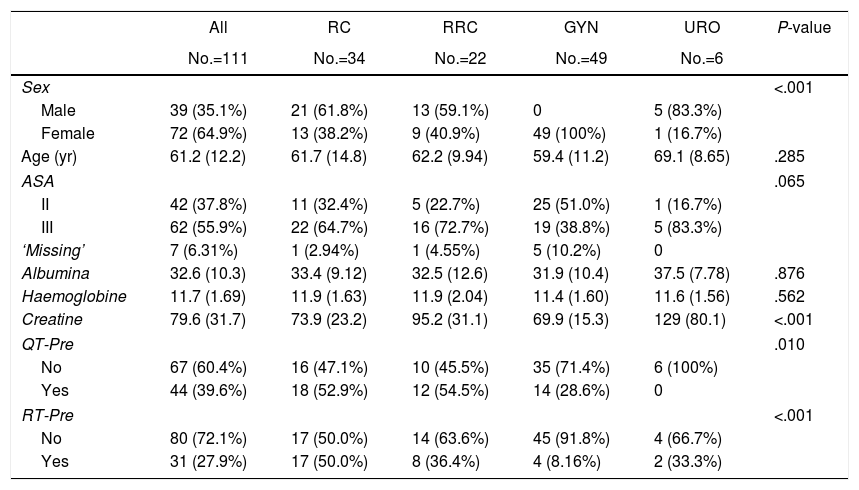

The distribution of preoperative treatment and variables is reported in Table 1 stratified by primary malignancy type. The overall median age was 61.2 years and 35.1% of patients were men. There were no differences in hemoglobin levels, renal function (measured by creatinine), nutritional status (measured by albumin), comorbidities or ASA score.

Preoperative Variables Stratified by Primary Malignancy Type.

| All | RC | RRC | GYN | URO | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=111 | No.=34 | No.=22 | No.=49 | No.=6 | ||

| Sex | <.001 | |||||

| Male | 39 (35.1%) | 21 (61.8%) | 13 (59.1%) | 0 | 5 (83.3%) | |

| Female | 72 (64.9%) | 13 (38.2%) | 9 (40.9%) | 49 (100%) | 1 (16.7%) | |

| Age (yr) | 61.2 (12.2) | 61.7 (14.8) | 62.2 (9.94) | 59.4 (11.2) | 69.1 (8.65) | .285 |

| ASA | .065 | |||||

| II | 42 (37.8%) | 11 (32.4%) | 5 (22.7%) | 25 (51.0%) | 1 (16.7%) | |

| III | 62 (55.9%) | 22 (64.7%) | 16 (72.7%) | 19 (38.8%) | 5 (83.3%) | |

| ‘Missing’ | 7 (6.31%) | 1 (2.94%) | 1 (4.55%) | 5 (10.2%) | 0 | |

| Albumina | 32.6 (10.3) | 33.4 (9.12) | 32.5 (12.6) | 31.9 (10.4) | 37.5 (7.78) | .876 |

| Haemoglobine | 11.7 (1.69) | 11.9 (1.63) | 11.9 (2.04) | 11.4 (1.60) | 11.6 (1.56) | .562 |

| Creatine | 79.6 (31.7) | 73.9 (23.2) | 95.2 (31.1) | 69.9 (15.3) | 129 (80.1) | <.001 |

| QT-Pre | .010 | |||||

| No | 67 (60.4%) | 16 (47.1%) | 10 (45.5%) | 35 (71.4%) | 6 (100%) | |

| Yes | 44 (39.6%) | 18 (52.9%) | 12 (54.5%) | 14 (28.6%) | 0 | |

| RT-Pre | <.001 | |||||

| No | 80 (72.1%) | 17 (50.0%) | 14 (63.6%) | 45 (91.8%) | 4 (66.7%) | |

| Yes | 31 (27.9%) | 17 (50.0%) | 8 (36.4%) | 4 (8.16%) | 2 (33.3%) | |

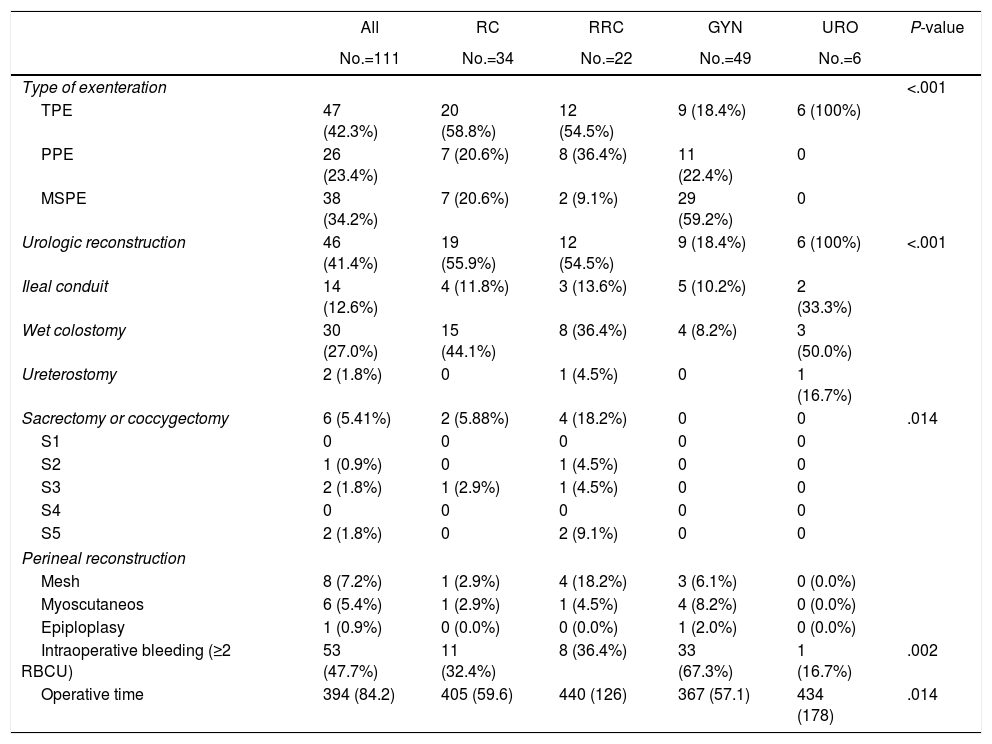

Surgical and intraoperative data are reported in Table 2. TPE was performed in 47 patients, MSPE in 36 patients and PPE in 28 patients. Most patients with gynecological tumor (29/49, 59.18%) underwent MSPE. Sacrectomy or coccygectomy was performed in 5 patients. The mean duration of surgery was 394min. There was a significantly shorter operating time for gynecological tumor. After MSPE, 36 colorectal anastomosis were performed: 29 without diverting ileostomy in gynecological patients (ovarian cancer, 100%) and 7 in primary or recurrent rectal patients. Six of these seven patients underwent temporary ileostomy. Four of the 6 ileostomies were subsequently reversed. Urologic reconstruction following TPE, consisted on DBWC in 30 patients, BIC in 14 patients, ureterocutaneostomy in 2 patients and 1 missed patient. Perineal reconstruction was required in 12.6% of patients including 6 flap reconstructions and 8 mesh reconstructions.

Surgical and Intraoperative Data Stratified by Primary Malignancy Type.

| All | RC | RRC | GYN | URO | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=111 | No.=34 | No.=22 | No.=49 | No.=6 | ||

| Type of exenteration | <.001 | |||||

| TPE | 47 (42.3%) | 20 (58.8%) | 12 (54.5%) | 9 (18.4%) | 6 (100%) | |

| PPE | 26 (23.4%) | 7 (20.6%) | 8 (36.4%) | 11 (22.4%) | 0 | |

| MSPE | 38 (34.2%) | 7 (20.6%) | 2 (9.1%) | 29 (59.2%) | 0 | |

| Urologic reconstruction | 46 (41.4%) | 19 (55.9%) | 12 (54.5%) | 9 (18.4%) | 6 (100%) | <.001 |

| Ileal conduit | 14 (12.6%) | 4 (11.8%) | 3 (13.6%) | 5 (10.2%) | 2 (33.3%) | |

| Wet colostomy | 30 (27.0%) | 15 (44.1%) | 8 (36.4%) | 4 (8.2%) | 3 (50.0%) | |

| Ureterostomy | 2 (1.8%) | 0 | 1 (4.5%) | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | |

| Sacrectomy or coccygectomy | 6 (5.41%) | 2 (5.88%) | 4 (18.2%) | 0 | 0 | .014 |

| S1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S2 | 1 (0.9%) | 0 | 1 (4.5%) | 0 | 0 | |

| S3 | 2 (1.8%) | 1 (2.9%) | 1 (4.5%) | 0 | 0 | |

| S4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S5 | 2 (1.8%) | 0 | 2 (9.1%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Perineal reconstruction | ||||||

| Mesh | 8 (7.2%) | 1 (2.9%) | 4 (18.2%) | 3 (6.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Myoscutaneos | 6 (5.4%) | 1 (2.9%) | 1 (4.5%) | 4 (8.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Epiploplasy | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Intraoperative bleeding (≥2 RBCU) | 53 (47.7%) | 11 (32.4%) | 8 (36.4%) | 33 (67.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | .002 |

| Operative time | 394 (84.2) | 405 (59.6) | 440 (126) | 367 (57.1) | 434 (178) | .014 |

TPE: total pelvic exenteration, PPE: posterior pelvic exenteration, MSPE: modified supralevator pelvic exenteration, RCCU: red cell concentrate unit.

Intraoperative blood transfusion of 2 or more red cell concentrates units was needed in 53 patients (47.0%).

Most common tumors types were adenocarcinoma (87.5%) for primary and recurrent rectal cancer, serous adenocarcinoma ovarian cancer (37.7%) for gynecological tumors and bladder infiltrating transitional cell carcinoma (50%) for urological tumors. Other gynecological tumors were adenocarcinoma ovarian cancer (10 cases), recurrent endometriod tumor (9 cases), clear-cell ovarian tumor (6 cases), recurrent squamous cell carcinoma (6 cases).

In 10 patients, malignant cells were not found during pathological examination. Two of them underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and results were interpreted as pathological complete response. In 8 patients, the previous diagnostic was not confirmed after surgery. Three patients with suspected rectal cancer recurrence showed inflammatory adhesions and 5 patients with previous radiotherapy for cervix or vulva epidermoid cancer showed actinic inflammatory response. These 8 patients were excluded for analysis of OS, local and distant recurrence rate.

Five patients were excluded for analysis of OS, LR and DR rate due to lost to follow-up and 1 patient was excluded for analysis of OS, LR and DR rate according to type of resection and margin status due to incomplete pathological report.

Resection margins were negative or R0 in 66 of 97 patients (68%). There was no difference in the percentage of R0 resections depending on the type of tumor. In 31 patients (32%), resection margins were positive, 21 R1 and 10 R2.

Mean number of lymph node resected was 20.1 (SD: 12.7). Nodal invasion was present in a total of 31 patients (44.3%).

Complementary oncologic treatments consisted in neoadjuvant therapy in 75 patients, radiotherapy in 31, and chemotherapy in 44 patients.

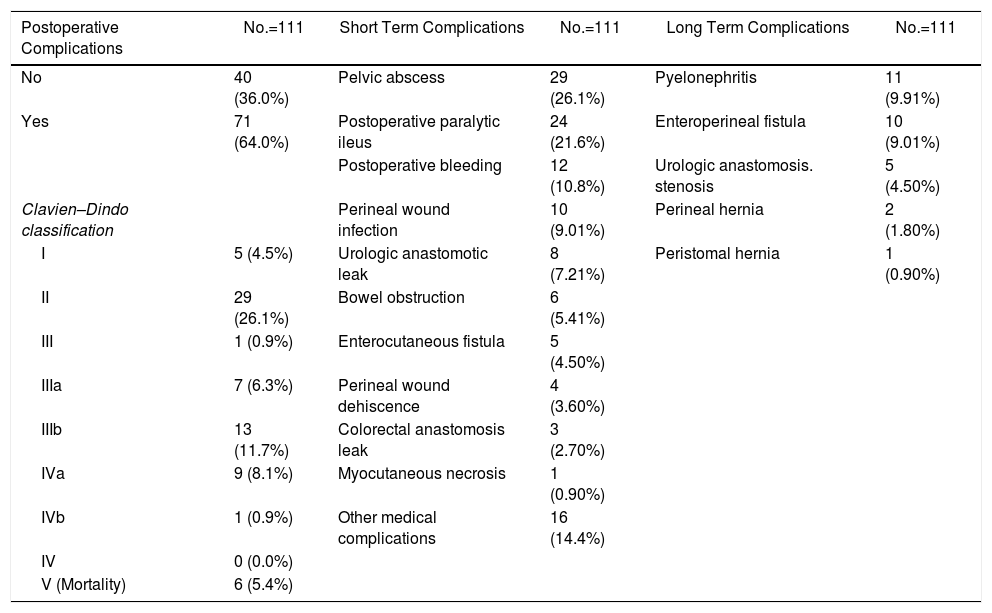

Overall, 71 patients (64%) developed at least one post-operative complication, 26.1% were considered in group II of Clavien–Dindo classification. The most common postoperative complications were pelvic abscess (26.1%), postoperative ileus (21.6%). Six patients (5.41%) needed a re-operation due to bowel obstruction. Twelve patients (10.8%) presented postoperative bleeding (needing 2 or more red cell concentrates units), 6 of them were treated by endovascular techniques or re-operation. Early postoperative complications are detailed in Table 3. Three (8.33%) of 36 patients with colorectal anastomosis developed anastomotic leak, all of them in the gynecological tumor group. Of these three patients, one needed end colostomy, one required percutaneous drainage and the third patient died for septic shock. The most common early urological complication was urine leak occurring in 6 patients (13% of patients with urological reconstruction). Three patients leaked after Bricker procedure (21%) and were managed by a nephrostomy in two cases and by ureteral reimplantation in the third. The other 3 patients leaked after DBWC (10%) and were treated conservatively in two cases and by ureteral reimplantation in the last patient. The most common late urological complications were pyelonephritis (12.6%) which occurred in 11 cases (3 patients after BIC, 7 patients after DBWC and one of them after ureterocutaneostomy), enteroperineal fistula (9%), and stenosis of urologic anastomosis in 4 patients (3.6%) (2 patients after BIC and two ones after DBWC).

Postoperative Complications. Short and Long Term Results.

| Postoperative Complications | No.=111 | Short Term Complications | No.=111 | Long Term Complications | No.=111 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 40 (36.0%) | Pelvic abscess | 29 (26.1%) | Pyelonephritis | 11 (9.91%) |

| Yes | 71 (64.0%) | Postoperative paralytic ileus | 24 (21.6%) | Enteroperineal fistula | 10 (9.01%) |

| Postoperative bleeding | 12 (10.8%) | Urologic anastomosis. stenosis | 5 (4.50%) | ||

| Clavien–Dindo classification | Perineal wound infection | 10 (9.01%) | Perineal hernia | 2 (1.80%) | |

| I | 5 (4.5%) | Urologic anastomotic leak | 8 (7.21%) | Peristomal hernia | 1 (0.90%) |

| II | 29 (26.1%) | Bowel obstruction | 6 (5.41%) | ||

| III | 1 (0.9%) | Enterocutaneous fistula | 5 (4.50%) | ||

| IIIa | 7 (6.3%) | Perineal wound dehiscence | 4 (3.60%) | ||

| IIIb | 13 (11.7%) | Colorectal anastomosis leak | 3 (2.70%) | ||

| IVa | 9 (8.1%) | Myocutaneous necrosis | 1 (0.90%) | ||

| IVb | 1 (0.9%) | Other medical complications | 16 (14.4%) | ||

| IV | 0 (0.0%) | ||||

| V (Mortality) | 6 (5.4%) |

Six deaths (5.4%) occurred within 30 days due to bleeding, anastomotic leakage, respiratory insufficiency and cardiac arrest.

Mean time of follow-up was 8.5 months (SD: 4.3). The reasons for mortality were cancer progression in 41 patients and non-oncologic reasons in 13 patients. Local recurrence was diagnosed in 27 patients within a mean of 17.3 (SD: 14.6) months while distant metastasis were diagnosed in 27 patients within a mean of 17.1 (SD: 12.1) months.

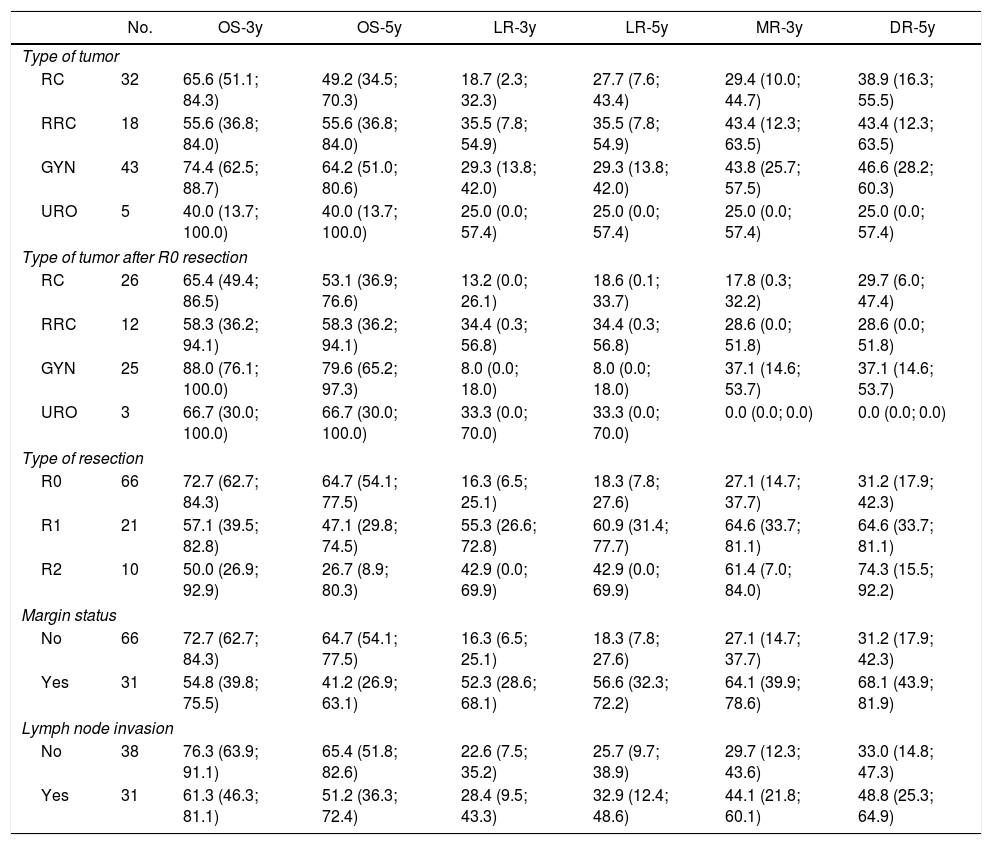

The 3 and 5-year OS, LR and DR for type of tumor, type of tumor following R0 resection, resection margin status and nodal invasion are shown in Table 4.

Three and Five-Year Overall Survival, Local Recurrence and Distal Recurrence.

| No. | OS-3y | OS-5y | LR-3y | LR-5y | MR-3y | DR-5y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of tumor | |||||||

| RC | 32 | 65.6 (51.1; 84.3) | 49.2 (34.5; 70.3) | 18.7 (2.3; 32.3) | 27.7 (7.6; 43.4) | 29.4 (10.0; 44.7) | 38.9 (16.3; 55.5) |

| RRC | 18 | 55.6 (36.8; 84.0) | 55.6 (36.8; 84.0) | 35.5 (7.8; 54.9) | 35.5 (7.8; 54.9) | 43.4 (12.3; 63.5) | 43.4 (12.3; 63.5) |

| GYN | 43 | 74.4 (62.5; 88.7) | 64.2 (51.0; 80.6) | 29.3 (13.8; 42.0) | 29.3 (13.8; 42.0) | 43.8 (25.7; 57.5) | 46.6 (28.2; 60.3) |

| URO | 5 | 40.0 (13.7; 100.0) | 40.0 (13.7; 100.0) | 25.0 (0.0; 57.4) | 25.0 (0.0; 57.4) | 25.0 (0.0; 57.4) | 25.0 (0.0; 57.4) |

| Type of tumor after R0 resection | |||||||

| RC | 26 | 65.4 (49.4; 86.5) | 53.1 (36.9; 76.6) | 13.2 (0.0; 26.1) | 18.6 (0.1; 33.7) | 17.8 (0.3; 32.2) | 29.7 (6.0; 47.4) |

| RRC | 12 | 58.3 (36.2; 94.1) | 58.3 (36.2; 94.1) | 34.4 (0.3; 56.8) | 34.4 (0.3; 56.8) | 28.6 (0.0; 51.8) | 28.6 (0.0; 51.8) |

| GYN | 25 | 88.0 (76.1; 100.0) | 79.6 (65.2; 97.3) | 8.0 (0.0; 18.0) | 8.0 (0.0; 18.0) | 37.1 (14.6; 53.7) | 37.1 (14.6; 53.7) |

| URO | 3 | 66.7 (30.0; 100.0) | 66.7 (30.0; 100.0) | 33.3 (0.0; 70.0) | 33.3 (0.0; 70.0) | 0.0 (0.0; 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0; 0.0) |

| Type of resection | |||||||

| R0 | 66 | 72.7 (62.7; 84.3) | 64.7 (54.1; 77.5) | 16.3 (6.5; 25.1) | 18.3 (7.8; 27.6) | 27.1 (14.7; 37.7) | 31.2 (17.9; 42.3) |

| R1 | 21 | 57.1 (39.5; 82.8) | 47.1 (29.8; 74.5) | 55.3 (26.6; 72.8) | 60.9 (31.4; 77.7) | 64.6 (33.7; 81.1) | 64.6 (33.7; 81.1) |

| R2 | 10 | 50.0 (26.9; 92.9) | 26.7 (8.9; 80.3) | 42.9 (0.0; 69.9) | 42.9 (0.0; 69.9) | 61.4 (7.0; 84.0) | 74.3 (15.5; 92.2) |

| Margin status | |||||||

| No | 66 | 72.7 (62.7; 84.3) | 64.7 (54.1; 77.5) | 16.3 (6.5; 25.1) | 18.3 (7.8; 27.6) | 27.1 (14.7; 37.7) | 31.2 (17.9; 42.3) |

| Yes | 31 | 54.8 (39.8; 75.5) | 41.2 (26.9; 63.1) | 52.3 (28.6; 68.1) | 56.6 (32.3; 72.2) | 64.1 (39.9; 78.6) | 68.1 (43.9; 81.9) |

| Lymph node invasion | |||||||

| No | 38 | 76.3 (63.9; 91.1) | 65.4 (51.8; 82.6) | 22.6 (7.5; 35.2) | 25.7 (9.7; 38.9) | 29.7 (12.3; 43.6) | 33.0 (14.8; 47.3) |

| Yes | 31 | 61.3 (46.3; 81.1) | 51.2 (36.3; 72.4) | 28.4 (9.5; 43.3) | 32.9 (12.4; 48.6) | 44.1 (21.8; 60.1) | 48.8 (25.3; 64.9) |

RC: rectal cancer, RRC: recurrent rectal cancer, GYN: gynecological tumors, URO: urological tumors.

R0: microscopically clear resection margins of at least 1mm; R1: microscopically involved resection margin with tumor within 1mm of the resection margin; R2: macroscopically involved resection margin.

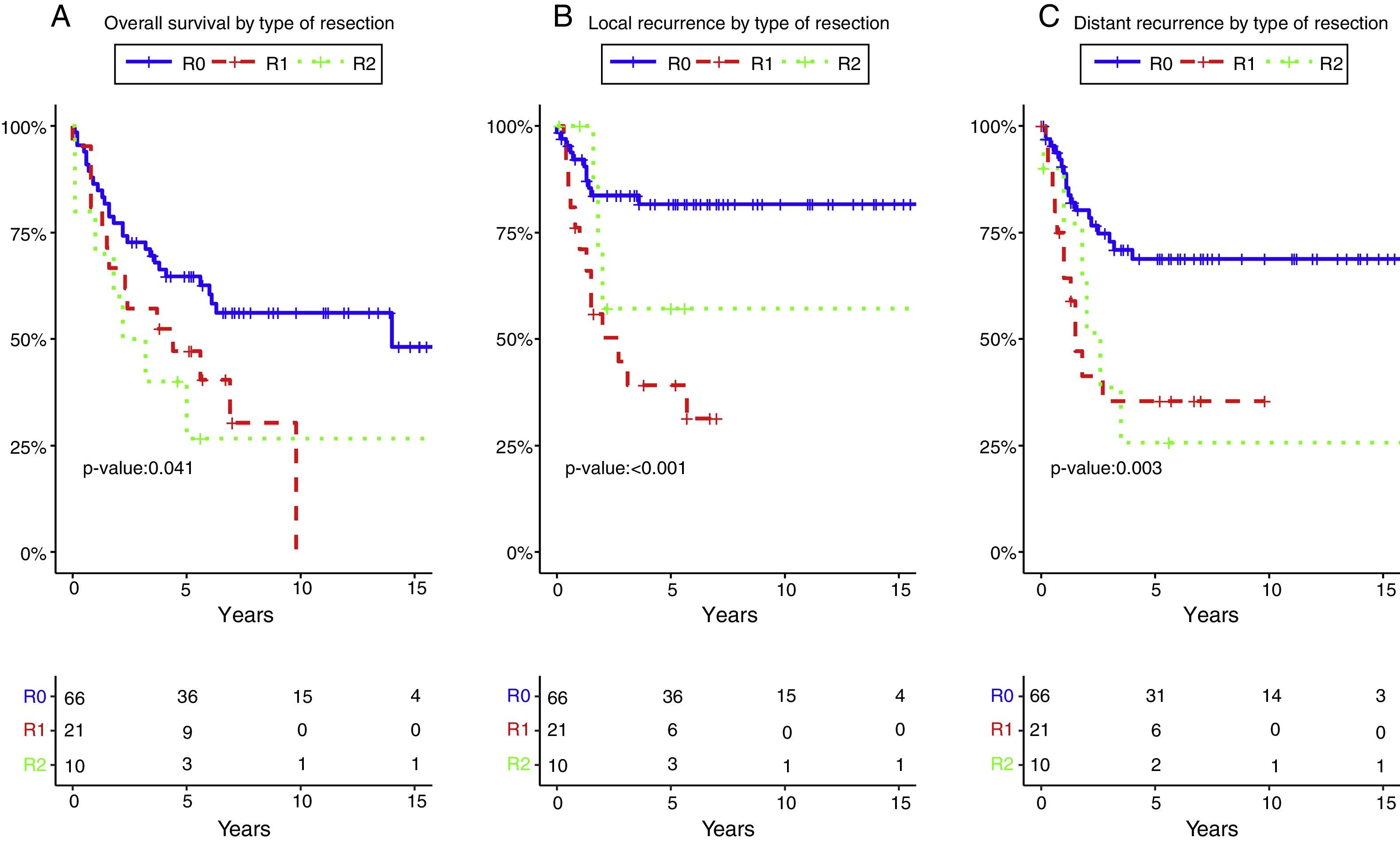

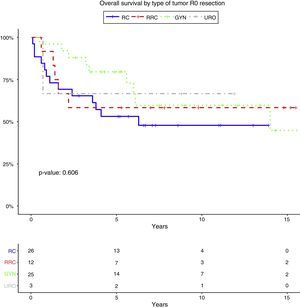

The 5-year OS according with the type of tumor (all resections included) and with R0 (excluding R1–R2 resections) was 49.2% and 53.1% for rectal cancer, 55.6% and 58.3% for recurrent rectal cancer, 64.2% and 79.6% for gynecological tumors, 40% and 66.7% for urologic tumors. The 5-year OS following complete resection (R0) was 64.7%. It was lower for those with residual disease: 47.1% for R1, and 26.7% for R2 (P=.041).

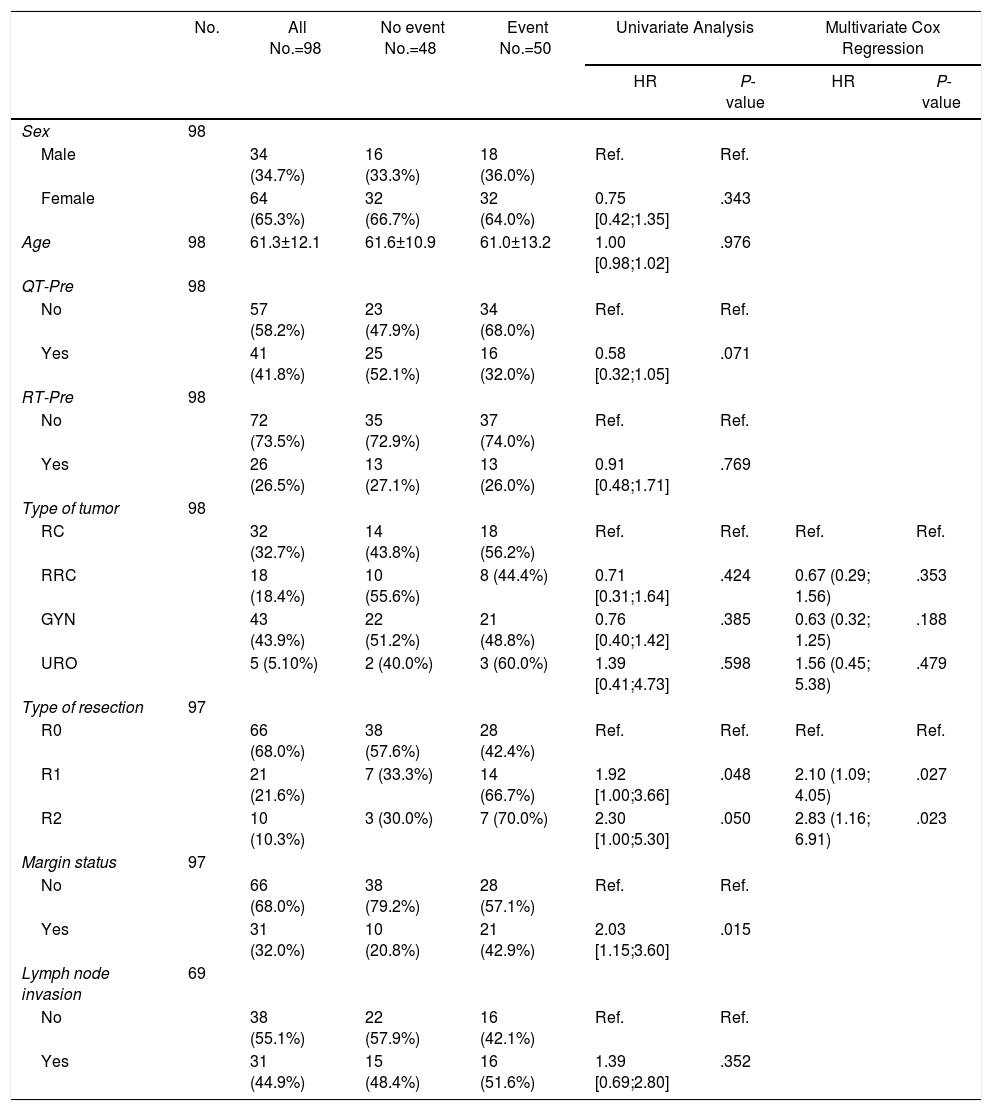

Tables 5–7 describe the analysis of prognostic factors. The univariate analysis showed that sex, age, tumor type, neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy or node status were not associated with OS, nor with local or distant recurrence. Following R0 resection, the type of tumor was not a prognostic factor of OS (Fig. 2).

Prognostic Factors for Overall Survival.

| No. | All No.=98 | No event No.=48 | Event No.=50 | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Cox Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | P-value | HR | P-value | |||||

| Sex | 98 | |||||||

| Male | 34 (34.7%) | 16 (33.3%) | 18 (36.0%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Female | 64 (65.3%) | 32 (66.7%) | 32 (64.0%) | 0.75 [0.42;1.35] | .343 | |||

| Age | 98 | 61.3±12.1 | 61.6±10.9 | 61.0±13.2 | 1.00 [0.98;1.02] | .976 | ||

| QT-Pre | 98 | |||||||

| No | 57 (58.2%) | 23 (47.9%) | 34 (68.0%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 41 (41.8%) | 25 (52.1%) | 16 (32.0%) | 0.58 [0.32;1.05] | .071 | |||

| RT-Pre | 98 | |||||||

| No | 72 (73.5%) | 35 (72.9%) | 37 (74.0%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 26 (26.5%) | 13 (27.1%) | 13 (26.0%) | 0.91 [0.48;1.71] | .769 | |||

| Type of tumor | 98 | |||||||

| RC | 32 (32.7%) | 14 (43.8%) | 18 (56.2%) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| RRC | 18 (18.4%) | 10 (55.6%) | 8 (44.4%) | 0.71 [0.31;1.64] | .424 | 0.67 (0.29; 1.56) | .353 | |

| GYN | 43 (43.9%) | 22 (51.2%) | 21 (48.8%) | 0.76 [0.40;1.42] | .385 | 0.63 (0.32; 1.25) | .188 | |

| URO | 5 (5.10%) | 2 (40.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 1.39 [0.41;4.73] | .598 | 1.56 (0.45; 5.38) | .479 | |

| Type of resection | 97 | |||||||

| R0 | 66 (68.0%) | 38 (57.6%) | 28 (42.4%) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| R1 | 21 (21.6%) | 7 (33.3%) | 14 (66.7%) | 1.92 [1.00;3.66] | .048 | 2.10 (1.09; 4.05) | .027 | |

| R2 | 10 (10.3%) | 3 (30.0%) | 7 (70.0%) | 2.30 [1.00;5.30] | .050 | 2.83 (1.16; 6.91) | .023 | |

| Margin status | 97 | |||||||

| No | 66 (68.0%) | 38 (79.2%) | 28 (57.1%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 31 (32.0%) | 10 (20.8%) | 21 (42.9%) | 2.03 [1.15;3.60] | .015 | |||

| Lymph node invasion | 69 | |||||||

| No | 38 (55.1%) | 22 (57.9%) | 16 (42.1%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 31 (44.9%) | 15 (48.4%) | 16 (51.6%) | 1.39 [0.69;2.80] | .352 | |||

RC: rectal cancer, RRC: recurrent rectal cancer, GYN: gynecological tumors, URO: urological tumors.

R0: microscopically clear resection margins of at least 1mm; R1: microscopically involved resection margin with tumor within 1mm of the resection margin; R2: macroscopically involved resection margin.

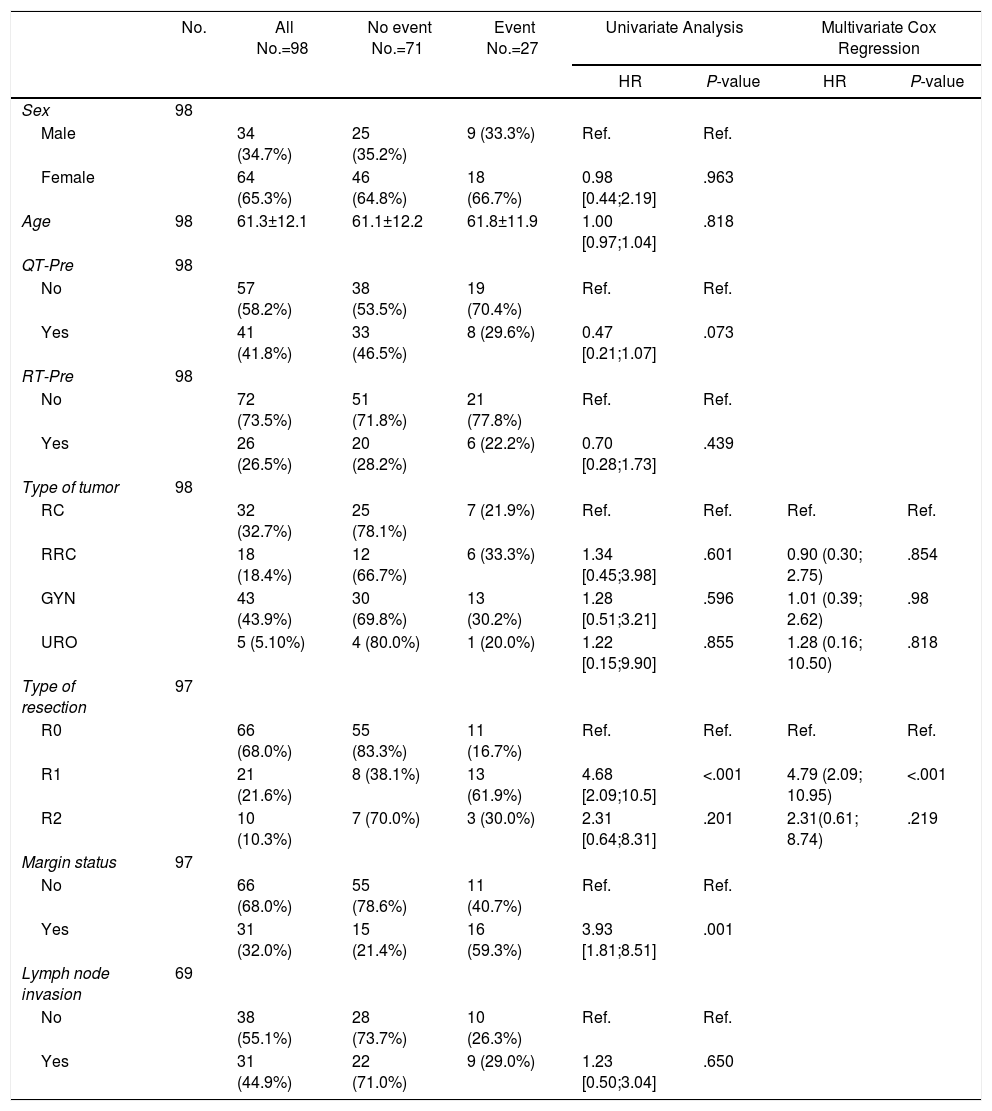

Prognostic Factors for Local Recurrence.

| No. | All No.=98 | No event No.=71 | Event No.=27 | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Cox Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | P-value | HR | P-value | |||||

| Sex | 98 | |||||||

| Male | 34 (34.7%) | 25 (35.2%) | 9 (33.3%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Female | 64 (65.3%) | 46 (64.8%) | 18 (66.7%) | 0.98 [0.44;2.19] | .963 | |||

| Age | 98 | 61.3±12.1 | 61.1±12.2 | 61.8±11.9 | 1.00 [0.97;1.04] | .818 | ||

| QT-Pre | 98 | |||||||

| No | 57 (58.2%) | 38 (53.5%) | 19 (70.4%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 41 (41.8%) | 33 (46.5%) | 8 (29.6%) | 0.47 [0.21;1.07] | .073 | |||

| RT-Pre | 98 | |||||||

| No | 72 (73.5%) | 51 (71.8%) | 21 (77.8%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 26 (26.5%) | 20 (28.2%) | 6 (22.2%) | 0.70 [0.28;1.73] | .439 | |||

| Type of tumor | 98 | |||||||

| RC | 32 (32.7%) | 25 (78.1%) | 7 (21.9%) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| RRC | 18 (18.4%) | 12 (66.7%) | 6 (33.3%) | 1.34 [0.45;3.98] | .601 | 0.90 (0.30; 2.75) | .854 | |

| GYN | 43 (43.9%) | 30 (69.8%) | 13 (30.2%) | 1.28 [0.51;3.21] | .596 | 1.01 (0.39; 2.62) | .98 | |

| URO | 5 (5.10%) | 4 (80.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 1.22 [0.15;9.90] | .855 | 1.28 (0.16; 10.50) | .818 | |

| Type of resection | 97 | |||||||

| R0 | 66 (68.0%) | 55 (83.3%) | 11 (16.7%) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| R1 | 21 (21.6%) | 8 (38.1%) | 13 (61.9%) | 4.68 [2.09;10.5] | <.001 | 4.79 (2.09; 10.95) | <.001 | |

| R2 | 10 (10.3%) | 7 (70.0%) | 3 (30.0%) | 2.31 [0.64;8.31] | .201 | 2.31(0.61; 8.74) | .219 | |

| Margin status | 97 | |||||||

| No | 66 (68.0%) | 55 (78.6%) | 11 (40.7%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 31 (32.0%) | 15 (21.4%) | 16 (59.3%) | 3.93 [1.81;8.51] | .001 | |||

| Lymph node invasion | 69 | |||||||

| No | 38 (55.1%) | 28 (73.7%) | 10 (26.3%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 31 (44.9%) | 22 (71.0%) | 9 (29.0%) | 1.23 [0.50;3.04] | .650 | |||

RC: rectal cancer, RRC: recurrent rectal cancer, GYN: gynecological tumors, URO: urological tumors.

R0: microscopically clear resection margins of at least 1mm; R1: microscopically involved resection margin with tumor within 1mm of the resection margin; R2: macroscopically involved resection margin.

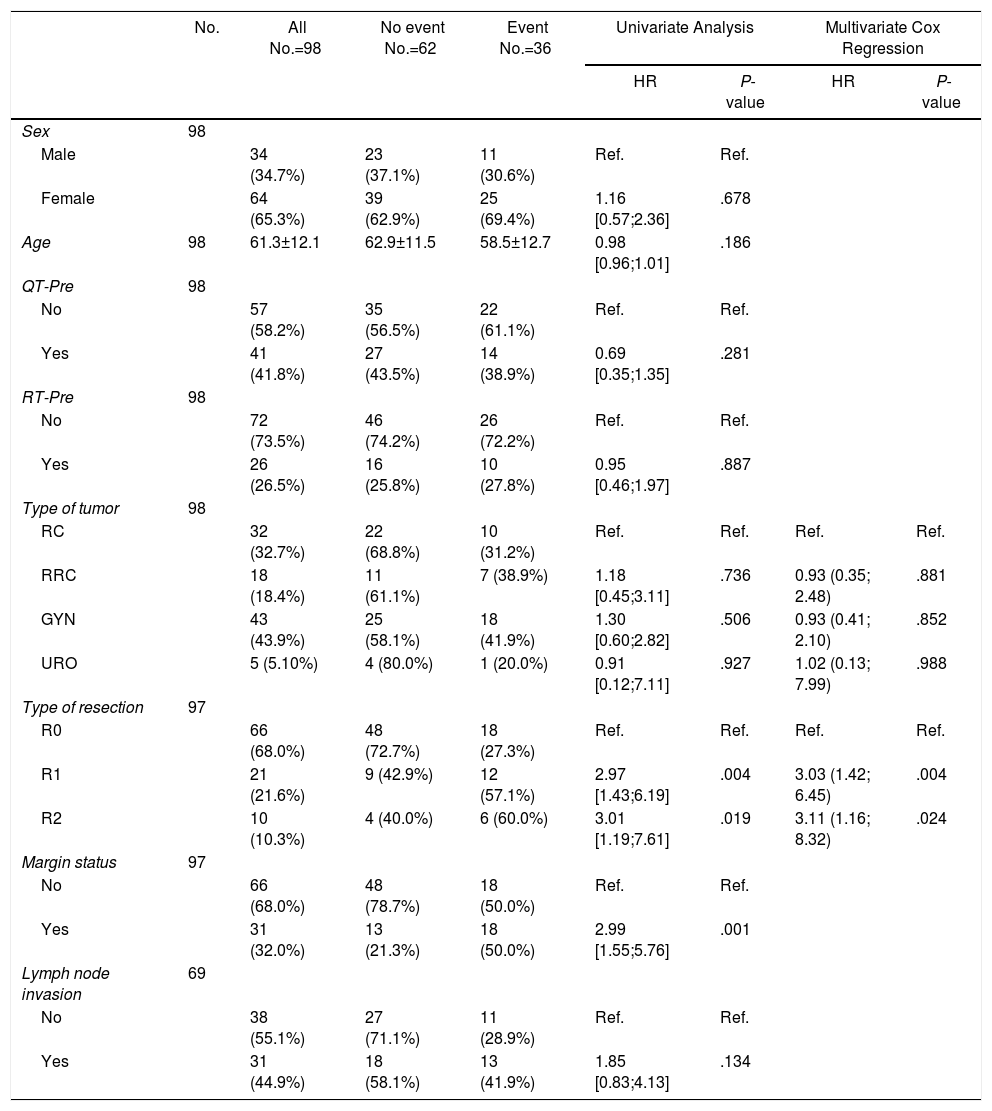

Prognostic Factors for Distal Recurrence.

| No. | All No.=98 | No event No.=62 | Event No.=36 | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Cox Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | P-value | HR | P-value | |||||

| Sex | 98 | |||||||

| Male | 34 (34.7%) | 23 (37.1%) | 11 (30.6%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Female | 64 (65.3%) | 39 (62.9%) | 25 (69.4%) | 1.16 [0.57;2.36] | .678 | |||

| Age | 98 | 61.3±12.1 | 62.9±11.5 | 58.5±12.7 | 0.98 [0.96;1.01] | .186 | ||

| QT-Pre | 98 | |||||||

| No | 57 (58.2%) | 35 (56.5%) | 22 (61.1%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 41 (41.8%) | 27 (43.5%) | 14 (38.9%) | 0.69 [0.35;1.35] | .281 | |||

| RT-Pre | 98 | |||||||

| No | 72 (73.5%) | 46 (74.2%) | 26 (72.2%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 26 (26.5%) | 16 (25.8%) | 10 (27.8%) | 0.95 [0.46;1.97] | .887 | |||

| Type of tumor | 98 | |||||||

| RC | 32 (32.7%) | 22 (68.8%) | 10 (31.2%) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| RRC | 18 (18.4%) | 11 (61.1%) | 7 (38.9%) | 1.18 [0.45;3.11] | .736 | 0.93 (0.35; 2.48) | .881 | |

| GYN | 43 (43.9%) | 25 (58.1%) | 18 (41.9%) | 1.30 [0.60;2.82] | .506 | 0.93 (0.41; 2.10) | .852 | |

| URO | 5 (5.10%) | 4 (80.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0.91 [0.12;7.11] | .927 | 1.02 (0.13; 7.99) | .988 | |

| Type of resection | 97 | |||||||

| R0 | 66 (68.0%) | 48 (72.7%) | 18 (27.3%) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| R1 | 21 (21.6%) | 9 (42.9%) | 12 (57.1%) | 2.97 [1.43;6.19] | .004 | 3.03 (1.42; 6.45) | .004 | |

| R2 | 10 (10.3%) | 4 (40.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | 3.01 [1.19;7.61] | .019 | 3.11 (1.16; 8.32) | .024 | |

| Margin status | 97 | |||||||

| No | 66 (68.0%) | 48 (78.7%) | 18 (50.0%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 31 (32.0%) | 13 (21.3%) | 18 (50.0%) | 2.99 [1.55;5.76] | .001 | |||

| Lymph node invasion | 69 | |||||||

| No | 38 (55.1%) | 27 (71.1%) | 11 (28.9%) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 31 (44.9%) | 18 (58.1%) | 13 (41.9%) | 1.85 [0.83;4.13] | .134 | |||

RC: rectal cancer, RRC: recurrent rectal cancer, GYN: gynecological tumors, URO: urological tumors, R0: microscopically clear resection margins of at least 1mm; R1: microscopically involved resection margin with tumor within 1mm of the resection margin; R2: macroscopically involved resection margin.

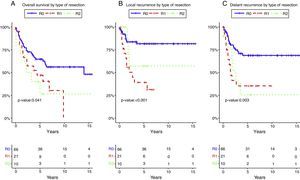

Resection margin status and positive margins were associated in the univariate analysis with lower OS (P=.041) (Fig. 3A), LR (P<.001) (Fig. 3B) and DR (P=.003) (Fig. 3C). After adjustment by type of tumor, the resection margin status was associated with lower OS, LR and DR.

Overall survival (A), local recurrence (B) and distant recurrence (C) according to the resection margin status. R0: microscopically clear resection margins of at least 1mm; R1: microscopically involved resection margin with tumor within 1mm of the resection margin; R2: macroscopically involved resection margin.

In the present study, it has been observed that morbidity and mortality rates after pelvic exenteration with rectal resection from different oncologic reasons, performed in referral centers and by experienced multidisciplinary surgical team, can be maintained in an acceptable range of value. Even so the rate of postoperative complications support the cooperation between different specializations.

In previous published series, pelvic exenteration has been associated with high morbidity and mortality rates.15,16 Morbidity has been reported to range from 37% to 100% and postoperative mortality varies between 0% and 25%.9 In the present study, the observed overall postoperative complication and mortality rates were 64% and 5.4% respectively. The most common postoperative complications were pelvic abscess, postoperative ileus and medical complications. Maintaining a low mortality is always a threshold for surgical indication particularly important when performing an aggressive procedure. Mortality reported in this series, in the low range of the literature, endorses the management of these patients. All the procedures were done by experienced colorectal surgeons and it could be one of the reasons of these results.

The indication of colorectal anastomosis and the role of covering ileostomy after pelvic exenteration is unclear due to the variability of primary and recurrent pelvic tumors, type of surgical procedures, level of anastomosis, possibility of adjuvant radiation and the poor nutritional status of the patients, being all these risk factors for colorectal anastomosis leak.17 However, in selected cases a colorectal anastomosis can be performed as there are no more preoperative risk factors than in a non extended rectal cancer surgery.

In this study, a protective ileostomy was performed in 6 patients on the basis of the risk factors previously described and due to the level of the anastomosis (under 7cm of the anal margin) when the tumor was primary or recurrent rectal cancer.18

When gynecologic oncologic surgery is considered, data concerning previous radiotherapy as a risk factor for anastomotic leak are scarce and retrospective. These data do not support that a proximal diversion should be always peformed.19,20 Depending on the type of tumor, anastomotic leak rates in the gynecologic scenario vary from 2.1% to 53.8% with the lowest average rate for ovarian cancer.21

In the presents series, diverting ileostomy was not constructed in any of the 29 colorectal anastomosis after ovarian cancer surgery due to the level of the anastomosis (higher than 7cm) and to the integrity of the inferior mesenteric artery since a high section of this artery is not necessary.22 Three of these non-diverted patients developed an anastomotic leak accounting for a 10% leak rate among patients with ovarian cancer, higher than the 0%–4% reported in the literature.23 Maybe, a more accurate selection among these kind of patients should be performed for the need of a covering ileostomy.

Urinary reconstruction after TPE consisted on 2 ureterostomies, 14 Bricker ileal conduits, both with terminal colostomy and 30 DBWC. Complications related to the urinary reconstruction have been reported from 45% to 65%. Urinary enteric anastomosis leaks and obstruction are the most common early complications (10%) while stenosis and fistulas, reported in up to 16% of patients,24 are the most frequent late urinary complications. Some authors referred that DBWC reconstruction could be associated with a higher risk of pyelonephritis and development of urinary reservoir neoplasia.25,26 However, as Teixera et al.27 referred in 2012, DBWC had less total complications including sepsis, leak and pelvic collections with comparatively no complications of a small bowel fistula. In this series, both types of urinary reconstruction showed a similar number of leaks and stenosis with a higher number of pyelonephritis after DBWC. Thus, DBWC can be considered a valid option even if further studies are necessary.

A study on multivisceral resections for rectal cancer identified a 5-year OS rate of 48%.28 In the present series a similar 5-years OS rate for rectal cancer following R0 resection was observed. In addition, type of malignancies following R0 resection was not a prognostic factor of OS.

Whether the original tumor is a primary or recurrent rectal, gynecological or urologic cancer, resection with clear margin has been shown to be the key for local control after pelvic exenteration for pelvic advanced malignancies.29 Kraybill et al.30 reported a 5-year survival rate of 25% in patients with positive margins versus 44% in patients with negative margins.

In this series, a 5-year survival rate of 64.7% in patients with negative margins versus 41.2% in patients with positive margins is reported. Moreover, surgical margins status was the only variable which showed significant influence on overall survival, local and distal recurrence.

The variability of pelvic tumors and the multiple options of neoadjuvant therapy has to be considered a limitation of the present series. However, this study aims to analyze the feasibility and results of pelvic exenteration by varying malignancies where rectal resection was always associated. Actually, in all the series, a colorectal surgeon was involved and a considerable number of colorectal anastomosis was performed.

In conclusion, due to the surgical complexity, variability of oncological outcomes and postoperative morbidity, pelvic exenteration by any cause need to be performed in referral centers and by specialized surgeons. It seems reasonable to perform a colorectal anastomosis after modified supralevator pelvic exenteration for ovarian cancer, although further studies could help for the selection of patients for a covering stoma. Double barrelled wet colostomy can be considered a valid options for urologic reconstruction with results similar to the Bricker ileal conduit. The most important prognostic factor after pelvic exenteration for malignant pelvic tumors is the status of surgical margin.

Contribution of the AuthorsGarcía-Granero: Study design, data acquisition, work writing.

Biondo: Study design, article writing, study supervision.

Kreisler: Acquisition of data, interpretation of results, critical review.

Espin-Basany: Acquisition of data, interpretation of results, critical review.

González-Castillo: Acquisition of data, critical review.

Valverde: Acquisition of data, critical review.

Trenti: Acquisition of data, critical review.

Gil-Moreno: Acquisition, interpretation of results, critical review.

Conflicts of InterestThere are no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank Bernat Miguel, statistician and data manager of the Colorectal Surgery Unit, Bellvitge University Hospital and IDIBELL, for the statistical analysis.

Please cite this article as: Garcia-Granero A, Biondo S, Espin-Basany E, González-Castillo A, Valverde S, Trenti L, et al. Exenteración pelvica con resección rectal por neoplasias de distinto origen en dos centros de referencia. Cir Esp. 2018;96:138–148.