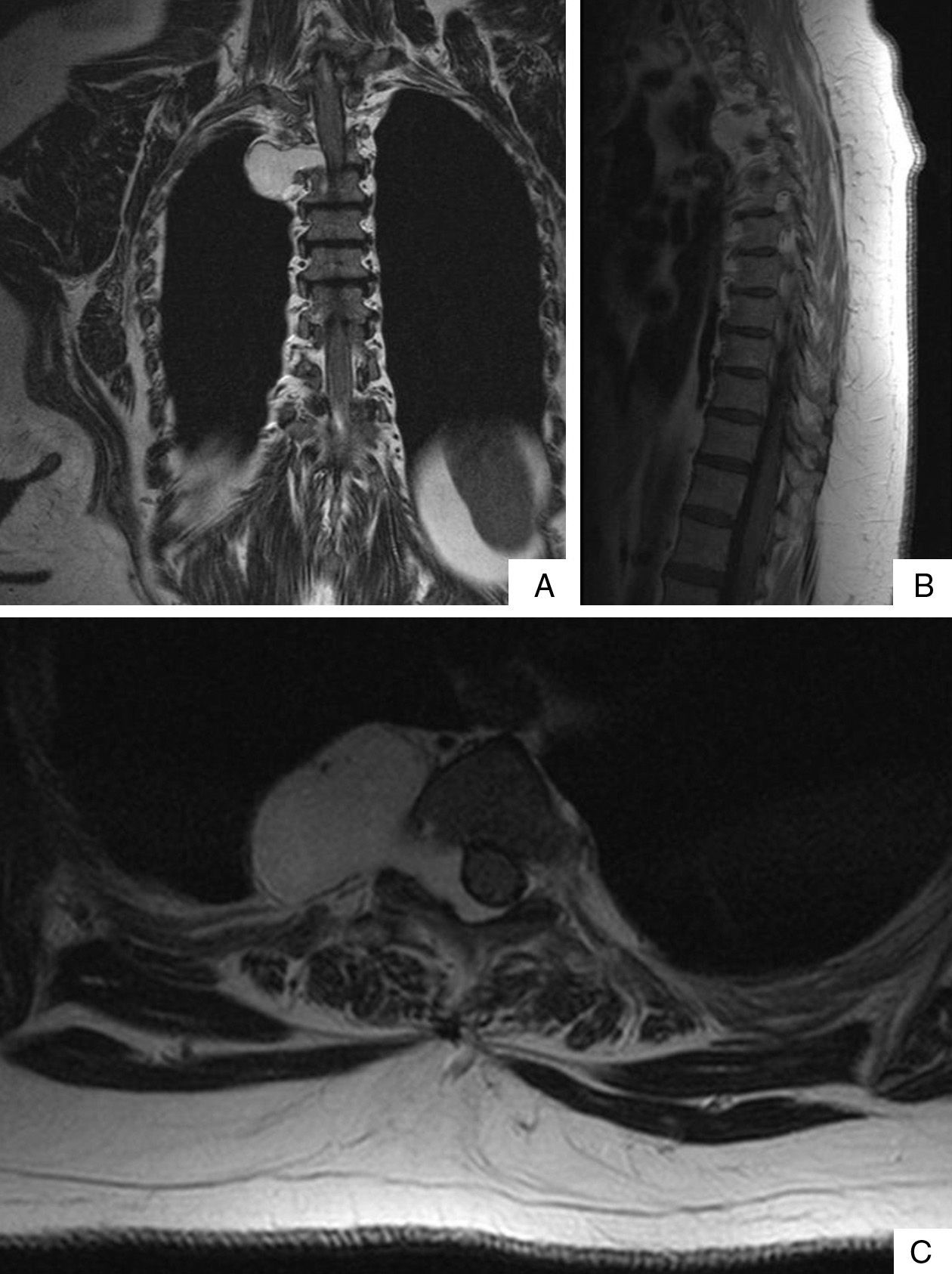

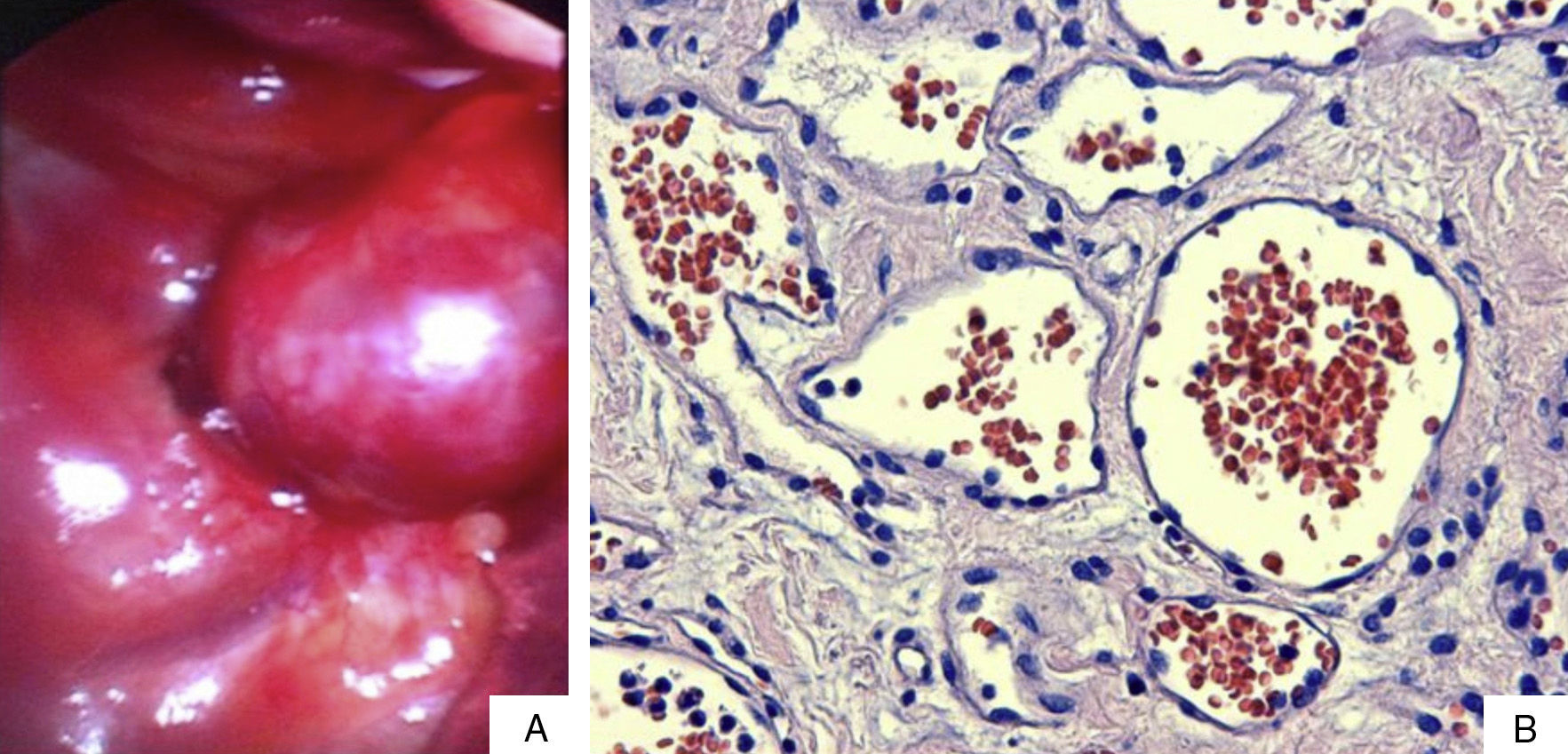

A woman aged 67 with a history of osteoarthritis of the knee was admitted to our centre to investigate a clinical history of weeks of difficulty in walking, dysaesthesia in both lower limbs and pain at the level of the spinal column. A computerised axial tomography scan (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed which revealed a well-defined 39mm×38mm lesion, in the shape of an hourglass, located at the posterior superior mediastinal level. The lesion extended towards the spinal column through vertebral foramina of T3 and T4, occupying the right part of the epidural space (Fig. 1). On assessing the case, it was decided that a combined surgical approach should be taken, initially resecting the epidural portion of the tumour and then the mediastinal part. With the patient under general anaesthetic, with selective bronchial intubation and positioned in the left lateral decubitus position, the neurosurgical team performed a laminectomy at T3–T4 level resecting the epidural portion of the tumour. Then the thoracic surgery team, with the right pulmonary parenchyma collapsed, performed a videothoracoscopy through three entry ports and a lesion, reddish in appearance, at the level of the posterior superior mediastinum was found. It was well defined and firmly anchored to the paravertebral space (Fig. 2a). The lesion bled easily on manipulation with the endo-instrument; therefore, an auxiliary anterior minithoracotomy was performed to free the mass safely. Once the tumour had been freed a communication orifice from the posterior mediastinum to the epidural space could be observed, created by the growth of the tumour. The anatomo-pathological study showed that the epidural portion of the tumour measured 13mm×1mm and the mediastinal portion was encapsulated and measured 35mm×2mm×25mm. The tumour was compatible with a cavernous haemangioma (Fig. 2b). The patients had an uneventful post-operative period and there was improvement of the symptoms on admission.

Mediastinal haemangiomas are extremely rare tumours with an incidence of less than 0.5% of all mediastinal tumours. They are considered vascular development anomalies rather than real neoplasias and rarely become malignant. Almost 50% of patients with mediastinal haemangiomas are asymptomatic and the majority does not require treatment. A few cases which are very large in size need surgical excision because they are affecting adjacent organs. The most common symptoms, which are caused by pulmonary compression, are cough, chest pain and dyspnoea. This case was exceptional for different reasons. Published cases of mediastinal cavernous haemangioma are extremely rare1 and there are none (as far as we are aware) about those which have invaded the epidural space, which makes the treatment using combined surgery necessary.

Radiologically, mediastinal haemangiomas appear as lobulated masses which are well defined on chest X-ray or CT scan. In 10% of cases they are associated with the appearance of phleboliths which are inherent to their vascular nature.2 CT scanning is very helpful in assessing the extent of the lesion and whether it has spread to adjacent structures. Angiography rarely detects signs that are suggestive of the vascular origin of the lesion. MRI is the gold standard test; mediastinal haemangiomas appear as slightly hyperintense lesions, and display heterogeneous intensities on T1 and high intensity on T2. These findings are very suggestive of the tumour's vascular origin. Positron emission tomography (pet) displays moderate FDG uptake.3 Histological confirmation of the diagnosis of mediastinal haemangioma is important since observation is the treatment of choice for asymptomatic lesions as they might resolve spontaneously. Nonetheless, the progression of the tumour needs to be observed as there are two histological varieties of mediastinal haemangioma: capillary and cavernous. Both varieties display different growth patterns.4 Unlike capillary haemangiomas, mediastinal cavernous haemangiomas do not resolve spontaneously. The problem is that it is very difficult to make a histological diagnosis of these tumours using methods which are not invasive. The method of diagnosis and treatment of choice is complete resection of the tumour. Haemorrhage is the main risk factor in surgical excision of these tumours. In cases where radical resection is not feasible, radiotherapy has been used as an alternative treatment.5

Please cite this article as: Fibla JJ, Molins L, Mier JM, Conesa G, García F. Hemangioma cavernoso del mediastino posterior invadiendo la columna vertebral: abordaje quirúrgico combinado. Cir Esp. 2013;91:681–683.