The term “desmoid” was coined by Muller in 1838 and is derived from the Greek word “desmos”, meaning band or tendon.1 Mesenteric fibromatosis accounts for approximately 0.03% of all malignant and benign neoplasms.2 It often arises from the abdominal wall or the extremities of parous women. It can also originate, though rarely, from the mesentery.3 It may be locally aggressive but does not metastasize. Its biological behavior is similar to that of fibrous lesions and fibrosarcoma. The most common symptoms are abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal mass on palpation, weight loss, and fever. The tumor may lead to complications such as small bowel or ureteric obstruction, intestinal perforation, enterocutaneous fistula, and intestinal hemorrhagia.4,5

A 57-year-old male presented to our hospital with complaints of abdominal pain, vomiting, distension, and swelling. The patient had been suffering abdominal discomfort for five years and had undergone two colonoscopic examinations in those five years, but no disorders had been found. Abdominal examination revealed distension, a metallic sound, muscular rigidity, and tenderness. X-ray examination revealed multiple air-fluid levels (Figure 1). An abdominal ultrasound showed a large solid mass in the right upper quadrant of the abdominal region. Since the intravesical pressure was measured as 25 cm H2O, the patient was diagnosed with mechanical intestinal obstruction, and laparotomy was performed following fluid and electrolyte replacement and antibiotic treatment. Abdominal exploration revealed an elastic hard tumor of 8×10 cm in diameter that appeared to originate from the jejunal mesentery, involving the third and fourth parts of the duodenum, the proximal jejunum and the ascending colon. The ascending colon, the proximal jejunum and the anterior face of the involved parts of the duodenum were surrounded by the mass. Thus, by right hemicolectomy, the first 60 cm massive small intestine and partial duodenum were exised to resect the mass en bloc. The proximal small bowel segment was anastomosed to the transverse colon in an end-to-side fashion, and the duodenum was sutured transversely. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was allowed to go home on the eighth postoperative day.

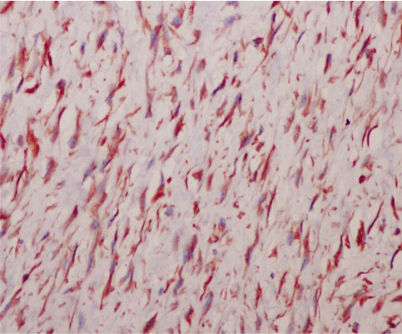

Microscopic examination revealed tumor cells, showing infiltrative progress in adipose tissue (Figure 2). The tumor cells had pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and were embedded in a collagen network interrupted by fibrotic sections, but mitosis was not seen (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that the tumor cells expressed vimentin and actin (Figure 4) but not S100, desmin, CD34 or CD117. Macroscopic examination, microscopic examination and immunohistochemical features were suggestive of an intraabdominal desmoid tumor.

Desmoid tumors are the most common primary tumors of the mesentery and constitute about 3.5% of all fibrous tissue tumors3,4 The difference in sex distribution is statistically insignificant, but there is a slightly higher incidence of this tumor in women than in men.7 There are two forms: the sporadic or primary form and the secondary form. The sporadic or primary form is extremely rare and is a variant of a benign stromal neoplasm of fibroblast-myofibroblast origin. It is usually secondary to trauma or hormonal stimulation or associated with familial polyposis coli or Gardner’s syndrome. Desmoid tumors have been seen in about 10% of familial adenomatous polyposis cases.8 At present, desmoid tumors are clinicopathologically classified into three types: abdominal, extra-abdominal and intra-abdominal.9 Desmoids of the abdominal wall are proliferative fibrous tumors, and extra-abdominal desmoids (desmoids outside the abdominal wall) are histologically the same as abdominal desmoids. Extra-abdominal desmoids are different in that they are usually invasive and spread even to areas surrounding deep blood vessels and nerves; in addition, they are difficult to remove completely and are likely to recur after surgery. Trauma may be a major factor precipitating the onset of this type of tumor. A definite episode of trauma has been noted in a high percentage of cases (19–63%).10 Accidental blunt injuries, lacerations, intramuscular injections, fractures, and different endocrine or genetic factors have also often been implicated.11 In the present case, symptoms were sporadic, and the patient had no previous history of any of the above conditions. Imaging techniques such as abdominal USG and CT are the most useful means for determining the exact localization of the tumor. In CT scans, a solid lesion is observed as a mass with soft tissue density.12

Most mesenteric tumors are large and appear in women in their reproductive years, often during or after pregnancy.6 Regression of these tumors has been associated with menopause and menarche.13,14 Lim et al. investigated the incidence and binding characteristics of the cytosol estrogen receptor and found that estrogen receptors were present in 33% of the desmoid tumors assayed.15 The signs and symptoms of mesenteric fibromatosis are insidious and usually manifest when there is a large palpable tumor resulting in abdominal discomfort or pain. Weight loss and symptoms of ureteral obstruction, mesenteric ischemia, or intestinal obstruction were observed in this patient. Mechanical intestinal obstruction is extremely rare, and we have seen only one previous case in the literature. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, lymphomas, carcinoid tumors, fibrosarcomas or inflammatory fibroid polyps should be considered in the differential diagnosis.16 Histologically, desmoid tumors are composed of long sweeping fascicles of differentiated fibroblastic cells with ill-defined cytoplasmic borders, delicately staining nucleoli, and rare mitosis. Unfortunately in some cases, the differential diagnosis between fibromatosis and well-differentiated fibrosarcoma (Grade I) is difficult.17 A variety of treatments, including wide surgical excision, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiestrogens, radiotherapy and cytotoxic chemotherapy have been attempted, but the efficacy of most of these is unpredictable. Treatment modalities other than surgical excision are controversial. Surgery should be performed by radical resection with wide margins, but these tumors are often unresectable because of massive involvement of adjacent vital structures. Wide excision is recommended, as these tumors have a tendency toward local recurrence.1,3–7,10,12,16 The principal chemotherapy drugs used are vinblastine, methotrexate, doxorubicin, dacarbazine and carboplatin. In addition, it has been shown that tamoxifen, either alone or in combination with indomethacin, has produced a good response.1,18 Despite radical surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy, recurrence rates in most studies can be in the range of 25–50%.19 However, recurrent disease can be resected, and patients may live for extended periods with recurrent disease, especially in cases of sporadic desmoids. In addition, Kollevold et al. have reported that a desmoid tumor temporarily regressed after salpingo-oophorectomy in a patient with breast cancer.20 Moreover, Baliski et al. have proposed that neoadjuvant treatment with doxorubicin and radiotherapy with delayed surgery is a better option than surgery alone.19 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first documented case of successful margin-negative resection of jejunal mesenteric intraabdominal fibromatosis by combined partial duodeno-jejunectomy and right hemicolectomy. The effects of radiation therapy on treatment are not obvious, but several reports have advocated that complete regression may be achieved using dose levels greater than 50 Gy. Furthermore, Nuyttens et al. have also reported that radiotherapy or surgery with radiotherapy results in a significantly lower local recurrence rate.12,21 Objective response was seen in 52% of patients with desmoid tumors treated with endocrine therapy.16 These tumors infiltrate the surrounding tissue and lead to severe morbidity and death. The frequency of local recurrence following excision is high, ranging from 10–90%. The significance of margins is a very controversial topic. Some studies suggest that margins are significant for predicting recurrence, while others claim that they are of no prognostic value.22,23 The patient presented in this report had a small bowel obstruction caused by mesenteric fibromatosis and underwent only an aggressive surgical operation without any postoperative adjuvant therapy. The patient has shown no signs of recurrence at present, 30 months after surgery. As a result, we may say that intra-abdominal desmoids are very rare and benign tumors but are very aggressive and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of mechanical intestinal obstruction.