Several studies have reported the benefits of exercise training for adults with HIV, although there is no consensus regarding the most efficient modalities. The aim of this study was to determine the effects of different types of exercise on physiologic and functional measurements in patients with HIV using a systematic strategy for searching randomized controlled trials. The sources used in this review were the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, MEDLINE, and PEDro from 1950 to August 2012. We selected randomized controlled trials examining the effects of exercise on body composition, muscle strength, aerobic capacity, and/or quality of life in adults with HIV. Two independent reviewers screened the abstracts using the Cochrane Collaboration's protocol. The PEDro score was used to evaluate methodological quality. In total, 29 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Individual studies suggested that exercise training contributed to improvement of physiologic and functional parameters, but that the gains were specific to the type of exercise performed. Resistance exercise training improved outcomes related to body composition and muscle strength, with little impact on quality of life. Aerobic exercise training improved body composition and aerobic capacity. Concurrent training produced significant gains in all outcomes evaluated, although moderate intensity and a long duration were necessary. We concluded that exercise training was shown to be a safe and beneficial intervention in the treatment of patients with HIV.

Advances in antiretroviral therapy have converted HIV infection into a chronic disease, resulting in patients with several comorbidities (1). HIV-related disability has been associated with decreased exercise capacity and impairment of patients' daily activities (2,3).

Thus, exercise training is a key strategy employed by patients with HIV or AIDS that is widely prescribed by rehabilitation professionals (4). The accumulated body of scientific evidence indicates that exercise training increases aerobic capacity, muscle strength, flexibility, and functional ability in patients with HIV or AIDS (5–7).

The exercise program should be modified according to an individual's physical function, health status, exercise response, and stated goals. The single workout must then be designed to reflect these targeted program goals, including the choice of exercises, the order of exercises, the volume (i.e., the number of repetitions, the number of sets, and the total time) of each exercise, and the intensity. Exercise intensity and volume are important determinants of physiologic responses to exercise training (6,7).

Adaptations to exercise are highly dependent on the specific type of training performed. However, there is no consensus regarding which modality and intensity are more effective in patients with HIV, making it difficult to choose the best training for this population. This issue is still an obstacle in clinical practice. A better understanding of the effectiveness and safety of exercise will enable people living with HIV and their health care providers to practice effective and appropriate exercise prescription (8).

The purpose of this report was to 1) perform a systematic review of the evidence regarding the effects of different types of exercise on health in HIV-infected patients and 2) to define the best volume, intensity, and type of exercise to achieve minimal and optimal health benefits in HIV-infected patients.

METHODSThis review comprised three phases. In phase 1, a database search (MEDLINE, LILACS, EMBASE, SciELO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), PEDro, and the Cochrane Library) was performed to identify relevant abstracts from up to August 2012. In the second phase, two reviewers assessed the list of studies generated by the search strategy, using the title and abstract to determine study eligibility. Full-text copies of potentially relevant studies were then obtained for detailed examination, and in phase 3, the quality of the studies was assessed.

Data Sources and SearchesWe performed a computer-based search, querying Ovid MEDLINE (1950 to August 2012), LILACS (up to August 2012), CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health, 1982 to August 2012), EMBASE (1980 to August 2012), PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials for original research articles published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese. In the search strategy, there were four groups of keywords: study design, participants, interventions, and outcome measures.

The study design group of keywords included the terms randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and controlled trials. The participants group included the terms human immunodeficiency virus, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, HIV, HIV infections, HIV long-term survivors, AIDS, and HIV/AIDS. The interventions group included the terms exercise, training, physical exercise, fitness, strength training, progressive resistive/resistance aerobic, aerobic training, concurrent strength and endurance training, concurrent training, anaerobic, exercise therapy, and physical training.

The outcome measures group included the terms quality of life, health-related quality of life, life expectancy, cardiopulmonary status, aerobic fitness, aerobic capacity, strength, muscle strength, body composition, health, physiologic parameters, and functional parameters.

Study SelectionTypes of studies and participantsWe included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing exercise training with non-exercise training or with another therapeutic modality. The exercise was performed at least two times per week and lasted at least 4 weeks. Studies on adults (18 years and older), regardless of sex and at all stages of infection, were included.

Types of interventionsResistance exercise (weight training or resistance training) was defined as exercise that requires muscle contraction against resistance (e.g., body weight or barbells). Resistance training programs were described with respect to duration, frequency, intensity, volume, rest intervals, muscle group, and supervision.

Aerobic exercise (or endurance training) was defined as a regimen containing aerobic interventions (walking, cycling, rowing, and stair stepping). Aerobic training programs were described with respect to intensity, frequency, duration, and supervision.

Concurrent training was defined as the application of aerobic and resistance exercise in the same training session.

Types of outcome measuresThis systematic review was limited to key indicators of different health outcomes known to be related to exercise in HIV-infected patients. Decisions regarding what health outcomes to include in the systematic review were made by examining what outcomes were studied in previously conducted RCTs and systematic reviews on HIV. These key indicators consisted of the following:

1) Anthropometric characteristics, as a measure of body composition;

2) Muscle strength, as a measure of musculoskeletal health;

3) Aerobic capacity or aerobic fitness, as a measure of cardiopulmonary health; and

4) Physical and psychological functioning, as a measure of quality of life.

The body composition measures considered in this review included but were not limited to anthropometry, lean body mass and fat mass, body mass index [calculated as weight (kg) divided by height2 (m)], and total body fat (the amount of subcutaneous fat determined using the thickness of specific skinfolds). Three trunk skinfolds (subscapular, suprailiac, and vertical abdominal) and four limb skinfolds (triceps, biceps, thigh, and medial calf); the waist circumference at the umbilicus, which is a measure of central fat (subcutaneous and visceral); and the maximum hip circumference were measured and recorded in mm. The waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) was the waist circumference at the umbilicus (mm) divided by the maximum hip circumference (mm).

The musculoskeletal health measures considered in this review also included skeletal muscle mass, muscle strength, a muscle function test, the maximum torque, the maximum force, the peak torque, the peak force, and total work.

The main cardiopulmonary measures considered in this review were the maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max/peak) (ml/kg/min), the absolute VO2, oxygen pulse (O2 pulse), the heart rate maximum (HRmax) (beats/min), the lactic acid threshold (LAT), fatigue (time on treadmill), exercise duration, and dyspnea (the rate of perceived exertion).

To assess the quality of life related to health, we reviewed studies that reported health-related quality of life based on standardized and validated scales or questionnaires.

Data extraction and quality assessmentAll authors worked independently and used a standard form adapted from the Cochrane Collaboration's (9) model for data extraction, considering 1) aspects of the study population, such as the average age and sex; 2) aspects of the intervention performed (sample size, type of exercise performed, presence of supervision, frequency, and duration of each session); 3) follow-up; 4) loss to follow-up; 5) outcome measures; and 6) presented results.

There are several scales for assessing the quality of RCTs. The PEDro scale assesses the methodological quality of a study based on important criteria, such as concealed allocation, intention-to-treat analysis, and the adequacy of follow-up. These characteristics make the PEDro scale a useful tool for assessing the quality of physical therapy and rehabilitation trials (10).

Methodological quality was independently assessed by two researchers. Studies were scored on the PEDro scale based on a Delphi list (11) that consisted of 11 items. One item on the PEDro scale (eligibility criteria) is related to external validity and is generally not used to calculate the method score, leaving a score range of 0 to 10 (12). Studies were excluded in the subsequent analysis if the cutoff of four points was not reached. Any disagreements were resolved by a third rater.

Data synthesis and analysisIf the inclusion criteria were not clearly described in a particular study, the authors were contacted, and a consensus among the reviewers was obtained to decide whether the study would be part of the review. We also performed a manual tracking of citations in the selected articles.

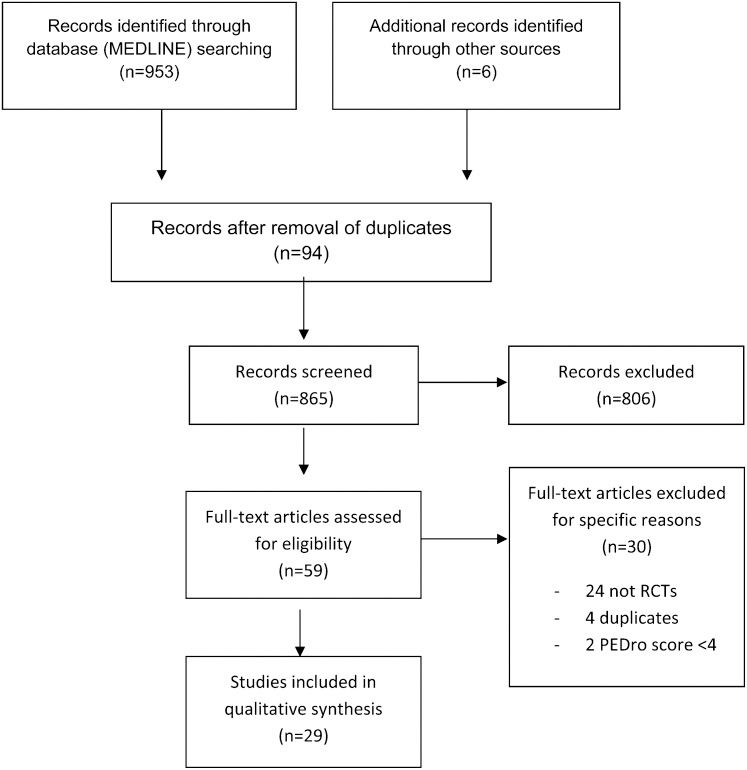

RESULTSThe flow chart for our study is shown in Figure 1. In total, 59 studies were sent to the reviewers for evaluation, selection, and inclusion in the review.

After assessment, 24 studies were excluded, and 35 papers met the entry criteria. Of these, four were duplicates (studies that used the same participants), as Sattler et al. 2002 (16) used the same participants as Sattler et al. 1999 (21); Lox et al. 1996 (22) used the same participants as Lox et al. 1995 (23); Multimura et al. 2008 (37) used the same participants as Multimura et al. 2008 (36); and Fairfield et al. 2001 (45) used the same participants as Grinspoon et al. 2000 (46).

The remaining 31 articles were fully analyzed and approved by both reviewers, and the data were extracted from each RCT. Each of the papers was assessed by both reviewers using PEDro scale methodology with the predefined cutoff (4). The results of the assessment using the PEDro scale are individually presented in Table 1. Two other studies [Galantino et al. 2006 (26) and McArthur et al. 1993 (33)] were excluded because these papers did not reach the defined minimal score on the PEDro scale.

Study quality on the PEDro scale.

| Study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sakkas et al. 2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ||

| 2 | Lindegaard et al. 2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||

| 3 | Shevitz et al. 2006 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ||

| 4 | Roubenoff et al. 2001 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||

| 5 | Agin et al. 2001 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||

| 6 | Bhasin et al. 2000 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | ||||||

| 7 | Strawford et al. 1999 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | |||

| 8 | Sattler et al. 1999 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | |||||||

| 9 | Lox et al. 1995 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||

| 10 | Spence et al. 1990 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||

| 11 | Terry et al. 2006 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||

| 12 | Galantino et al. 2001 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3∗) | |||||||

| 13 | Neidig et al. 2000 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | |||||||

| 14 | Smith et al. 2000 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||

| 15 | Baigis et al. 2002 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||

| 16 | Perna et al. 1999 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||

| 17 | Terry et al. 1999 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||

| 18 | Stringer et al. 1999 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||

| 19 | McArthur et al. 1993 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2∗) | ||||||||

| 20 | LaPerrieri et al. 1990 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||

| 21 | Yarakeshi et al. 2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||

| 22 | Multimura et al. 2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||

| 23 | Hand et al. 2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||

| 24 | Pérez-Moreno. 2007 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||||

| 25 | Dolan et al. 2006 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||||

| 26 | Filippas et al. 2006 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | |||

| 27 | Driscoll et al. 2004 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||

| 28 | Driscol et al. 2004 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||

| 29 | Rojas et al. 2003 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||

| 30 | Grispoon et al. 2000 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||

| 31 | Rigsby et al. 1992 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 |

Of the 29 articles included in this review, eight were on resistance exercise compared with a control or supplementation (13,15,17–21), eight were on aerobic exercise (25,27–32), compared with a control, 11 compared concurrent training with a control group (35,36,38–44,46), and two compared resistance exercise with aerobic exercise (14,23).

The participants included adults infected with HIV at various stages of the disease, with CD4 counts ranging from <100 to >500 cells/mm3. Patients with elements of wasting syndrome (either >5% or >10% involuntary weight loss or body weight <90% of the ideal body weight) were also included. The studies included patients of both sexes, but there was a predominance of males (77%). The sample sizes, outcomes, and results of the included studies with regard to different types of exercise are summarized in Table 2.

Characteristics of the outcomes and results of the trials included in the review.

| Study | Participants (M:F) | Outcomes | Outcomes | Results | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body composition (BC) | Muscle strength (MS) | >Aerobic capacity (AC) | HRQOL | BC | MS | AC | HRQOL | ||||

| 1 | Sakkas et al. 2009 | HIV 43 (42:1) | Body composition Muscle strength | DEXA MRI | 1RM testing Isometric MVC | NA | NA | ↑ LBM | ↑ RM MVC | NA | NA |

| 2 | Lindegaard et al. 2008 | HIV 20 (20:0) | BC Muscle strength Aerobic capacity | DEXA | 3RM testing | VO2max | NA | ↑ LBM ↓ BW | ↑ 3RM | ↑ VO2max | NA |

| 3 | Shevitz et al. 2005 | HIV 50 (33:14) | Body composition Muscle strength | DEXA CSMA | Isokinetic dynamometer 1RM testing | TCAM6 | HRQOL | ↑ CSMA | ↑ RM | ↑ TCAM6 | ↑ HRQOL |

| 4 | Roubenoff,2001 | HIV 20 (19:1) | Body composition Muscle strength HRQOL | DEXA | 1RM testing | NA | SF-36 | ↑ LBM | ↑ RM | NA | ↑ SF-36 |

| 5 | Agin et al. 2001 | HIV 43 (0:43) | BC Muscle strength HRQOL | DEXA MRI | 1RM testing | NA | MOS-HIV | ↑ LBM | ↑ RM | NA | ↑ MOS |

| 6 | Basin et al. 1999 | HIV 61 (NI:NI) | BC Muscle strength HRQOL | Anthropometric measurements DEXA MRI | 1RM testing | NA | HRQOL | ↑ LBM ↑ CSMA | ↑ RM | NA | ↑ HRQOL |

| 7 | Strawford et al. 1999 | HIV 24 (24:0) | Body composition Muscle strength HRQOL | DEXA | Isokinetic dynamometer 1RM testing | NA | NA | ↑ LBM | ↑ RM | NA | NA |

| 8 | Sattler et al. 1999 | HIV 33 (33:0) | Body composition Muscle strength | BIA DEXA MRI | 1RM testing | NA | NA | ↑ LBM ↑ CSMA | ↑ RM | NA | NA |

| 9 | Lox et al, 1995 | HIV 34 (34;0) | Body composition Aerobic capacity | Anthropometric measurements | 1RM testing | VO2max | NA | ↑ LBM | ↑ RM | NA | NA |

| 10 | Spence et al. 1990 | HIV 24 (24:0) | Body composition Muscle strength | Anthropometric measurements | Hand-held dynamometer | NA | NA | ↑ LBM | ↑ RM | NA | NA |

| 11 | Terry et al. 2006 | HIV 42 (32:10) | Body composition Aerobic capacity | Anthropometric measurements | NA | Treadmill stress test | NA | ↓ BW ↓ BF ↓ WHR | NA | ↑ VO2max | NA |

| 12 | Neidig et al. 2003 | HIV 60 (52:8) | Depression Aerobic capacity Stress | NA | NA | Graded exercise stress test | POMS | NA | NA | NA | ↑ POMS |

| 13 | Baigis et al. 2002 | HIV 123 (89:20) | Aerobic capacity HRQOL | NA | NA | Treadmill Stress test | MOS-HIV | NA | NA | - VO2max | - MOS-HIV |

| 14 | Smith et al. 2001 | HIV 60 (52:8) | Body composition Aerobic capacity | Anthropometric measurements | NA | Graded exercise test Time on treadmill | NA | ↓ BMI ↓ TBF | NA | ↑ TT - VO2max | NA |

| 15 | Perna et al. 1999 | HIV 43 (18:10) | Aerobic capacity | NA | NA | Graded exercise test | NA | NA | ↑ VO2peak ↑ O2 pulse | ||

| 16 | Terry et al. 1999 | HIV 21 (14:7) | Body composition Aerobic capacity | Anthropometric measurements | NA | Time on treadmill | NA | NI | NA | ↑ treadmill time | NA |

| 17 | Stringger et al. 1998 | HIV 34 (31:3) | Aerobic capacity HRQOL | NA | NA | Graded exercise test | QOL | NA | NA | ↑ VO2max | ↑ QOL |

| 18 | LaPerrieri et al. 1990 | HIV 50 (50:0) | Aerobic capacity | NA | NA | Bicycle ergometer test | NA | NA | NA | ↑ VO2max | NA |

| 19 | Yarasheski et al. 2010 | HIV 39 (34:5) | Body composition Muscle strength | DEXA | 1RM testing | NA | NA | ↑ LBM ↑ TMV | NA | NA | NA |

| 20 | Multimura et al. 2008a | HIV 97 (36:61) | Body composition Aerobic capacity HRQOL | Anthropometric measurements | NA | Shuttle test | WHOQOL-BREF | ↓ % BFM | NA | ↑ VO2peak | ↑ QOL |

| 21 | Hand et al. 2008 | HIV 40 (30:10) | Aerobic capacity | NA | NA | Graded treadmill stress test | NA | NA | NA | ↑ VO2peak | NA |

| 22 | Pérez-Moreno et al. 2007 | HIV 19 (19:0) | BC Strength AC HRQOL | Body mass MRI | 6RM testing | Stress test Cycle ergometer | QOL | NS | ↑ 6RM | ↑ VO2peak | NS |

| 23 | Dolan et al. 2006 | HIV 38 (0:38) | Body composition Aerobic capacity | Anthropometric measurements TC DEXA | 1RM testing | Treadmill stress test TCAM6 | NA | ↑ CSMA | ↑ 1 RM | ↑ VO2peak ↑ TCAM6 | NA |

| 24 | Filipas et al. 2006 | HIV 35 (35:0) | Aerobic capacity HRQOL | NA | 1RM testing | Kasch pulse recovery test | MOS-HIV | NA | NA | ↓ HR | ↑ MOS-HIV |

| 25 | Driscoll et al. 2004a | HIV 25 (20:5) | BC Strength Aerobic capacity | Anthropometric measurements DEXA TC | 1RM testing | Submaximal exercise stress test | NA | ↑ CSMA ↓ WHR | ↑ 1 RM | ↑ET | NA |

| 26 | Driscoll et al. 2004b | HIV 25 (20:5) | Body composition Muscle strength | Anthropometric measurements CT DEXA | 1RM testing | NA | NA | ↓ BMI ↓ TMA | NA | NA | NA |

| 27 | Rojas et al. 2003 | HIV 33 (23:10) | Aerobic capacity HRQOL | NA | NA | Graded exercise stress test | MOS-HIV | NA | NA | ↑ VO2max ↑ O2 pulse | ↑ MOS-HIV |

| 28 | Grinspoon et al. 2000 | HIV 43 (43:0) | BC Muscle strength | CT DEXA | 2RM testing | NA | NA | ↑ LBM ↑ CSMA | ↑ 1 RM | NA | NA |

| 29 | Rigsby et al. 1992 | HIV 37 (37:0) | Muscle strength Aerobic capacity | NA | 2RM testing | YMCA cycle test protocol/Cycle ergometer | NA | NA | ↑ 1 RM | ↑ET ↓ HR | NA |

Male and female (M/F), dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), lean body mass (LBM), body weight (BW), body cell mass (BCM), thigh muscle volume (TMV), percentage body fat (% BFM), thigh muscle adiposity (TMA), body fat (BF), total body fat (TBF), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) maximum voluntary contraction (MVC), mid-thigh cross-sectional muscle area (CSMA), 6 min walk test (TCAM6), exercise time (ET), time on treadmill (TT), health-related quality of life (HRQOL); Medical outcomes study HIV health survey (MOS-HIV); Profile of Mood States (POMS), not assessed (NA), significant improvement before and after the intervention and/or between groups (p<0.05) (↑), significant reduction before and after the intervention and/or between groups (p<0.05) (↓), no change (-), no improvement (NI).

The initial sample size of the selected studies ranged from 20 (13,17) to 61 (19). The final sample ranged from 20 (13,17) to 50 (15), and the mean age of the participants ranged from 18 to 60 years. All studies selected in this review included outpatients diagnosed with HIV, and most of these patients were receiving antiretroviral therapy. Four studies included patients of both sexes (13,15,17,19), six included only men (14), and one included only women (18).

Characteristics of intervention programsThe exercise intervention characteristics of the included studies are provided in Table 3. The parameters used in the application of resistance exercise were reported in most studies, and all studies described the progressive nature of the training.

Characteristics of the experimental intervention (resistance exercise) the trials included in the review.

| N | Study | Intensity (RM) | Volume | Muscle | Contraction | Frequency (x wk) | Time (min) | Duration (wk) | Supervision (yes/no) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sakkas et al. 2009 | 80% RM | 3 sets x 8 reps | Upper body Lower body | NI | 3 | 90 | 12 | yes |

| 2 | Lindegaard et al. 2008 | 50-60% RM 70-80% RM | 3 sets x 12 reps4 sets x 8-10 reps | Upper body Lower body | Concentric/Eccentric | 3 | 45-60 | 16 | NI |

| 3 | Shevitz et al. 2005 | 80% RM | 3 sets x 8 reps | Large muscles | Dynamics | 3 | 30-60 | 12 | yes |

| 4 | Roubenoff et al. 2001 | 50-60% RM 75-90% RM | 3 sets x 8 reps | Large muscles | NI | 3 | NI | 8 | yes |

| 5 | Agin et al. 2001 | 75% RM | 3× (8-10) reps | NI | NI | 3 | NI | 14 | yes |

| 6 | Bhasin et al. 2000 | 60% RM | 3× (12-15) reps | Upper body | NI | 3 | NI | 16 | NI |

| 70-90% RM | 4× (4-6) reps | Lower body | |||||||

| 7 | Strawford et al. 1999 | 80% RM | 3 sets x 10 reps | Major muscles | NI | 3 | 60 | 7 | yes |

| 8 | Sattler et al. 1999 | 70% RM | 3 sets x 8 reps | Upper body | Concentric | 3 | NI | 12 | yes |

| 80% RM | Lower body | Eccentric | |||||||

| 9 | Lox et al. 1995 | 60% RM | 3 sets x 10 reps | NI | NI | 3 | NI | 12 | yes |

| 10 | Spence et al. 1990 | 15 RM | 1 set x 15 reps 3 sets x 10 reps | Bilateral | Concentric | 3 | NI | 6 | yes |

RM = repetition maximum; reps = repetitions; NI = no information.

The duration of intervention programs with resistance ranged from 6 (24) to 16 (14,19) weeks, but in 40% of the reviewed studies, the application period was 12 weeks. The duration of the session varied from 30 (15) to 90 (13) minutes, although in six studies, the duration was not reported. The frequency of sessions was three times per week in all studies.

Only two studies (20,23) did not specify the type of muscle contraction performed during training. In the other studies, the exercise was performed with concentric and eccentric contractions using machines, weight stations, and free weights. The exercise intensity was based on the extent of the individual's one-repetition maximum (RM), ranging from 50 to 90% of the RM in 90% of the studies. One study described the intensity as the 15RM (24).

The application volume of exercise ranged from three to five sets of six to 15 repetitions (reps). In 70% of the studies, the volume was three sets of eight reps, but only two studies reported the time interval between the series, which ranged from 60 to 120 seconds (14,21). All studies reported the application of exercises to large muscle groups of the lower and upper limbs.

Aerobic exerciseCharacteristics of the sampleThe baseline sample in the selected studies ranged from 20 (14) to 123 (28) people. The final sample ranged from 18 (14) to 109 (28) people, and the mean age of the participants ranged from 18 to 60 years. Three studies only included males (14,23,34), and the remaining studies included HIV-infected patients of both sexes. All studies analyzed in this review included outpatients diagnosed with HIV, and most of these patients were receiving antiretroviral therapy.

Characteristics of intervention programsThe duration of the intervention programs with aerobic exercise ranged from 6 (32) to 24 (34) weeks. In 60% of the studies, the application of the program lasted 12 weeks. The session duration was reported in all studies and ranged from 30 (29,32) to 60 (25,27,31) minutes, with an average duration of 45 min. The frequency of the program was three times per week in all studies.

Most studies used either a cycle ergometer or combined exercise programs (such as a cycle ergometer and/or walking and/or jogging). The intensity of exercise was adjusted based on the HRmax in 70% of the studies. In one study (29), the VO2max/peak was used, and the heart rate reserve was used in another study (23). The intensity ranged from 50 to 85% of the HRmax, 50 to 85% of the VO2max/peak, or 50 to 85% of the heart rate reserve.

The aerobic interventions in the trials also varied according to constant compared with interval exercise and moderate compared with high-intensity exercise. Table 4 provides details on the characteristics of the intervention programs.

Characteristics of the experimental intervention (aerobic exercise) in the trials included in the review.

| Study | Modality | Intensity/duration (wk) | Volume | Frequency (x per wk) | Time (min) | Length (wk) | Supervision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lindegaard et al. 2008 | NI | 65% HRmax/8 75% HRmax/8 | 5 min warm-up 35 min IT | 3 | 40 | 16 | yes |

| 2 | Terry et al. 2006 | Run | 75-85% HRmax | 15 min warm-up 30 min exercise 15 min cool-down | 3 | 60 | 12 | yes |

| 3 | Neidig et al. 2003 | Treadmill Stationary bike Walking | 50-70% HRmax | 5 min warm-up 30 min exercise 5 min cool-down | 3 | 60 | 12 | yes |

| 4 | Baigis et al. 2002 | Fitness Master ski machine | 75-85% HRmax | 10 min warm up 20 min exercise 10 min cool-down | 3 | 40 | 15 | yes |

| 5 | Smith et al. 2001 | Walk or run Treadmill Jog | 60-80 VO2max | 5 min warm-up 30 min exercise 5 min cool-down | 3 | 30 | 12 | yes |

| 6 | Perna et al. 1999 | IT Cycling exercise | 70-80% HRmax | 3 min exercise task 2 min recovery | 3 | 45 | 12 | yes |

| 7 | Terry et al. 1999 | Treadmill | G1 - 60±4% HRmax | NI | 3 | 60 | 12 | yes |

| G2 - 80±4% HRmax | ||||||||

| 8 | Stringer et al. 1998 | Cycle ergometer | G3 MI G4 HI | 60 min IT 30-40 min IT | 3 | 30-60 | 6 | yes |

| 9 | Lox et al. 1995 | Bicycle ergometer | 50-80% HRres | 5 min warm-up 24 min exercise 15 min cool-down | 3 | 45 | 12 | yes |

| 10 | LaPerrieri et al. 1990 | Bicycle ergometer | 60-79% HRmax 80% HRmax | 3 min exercise 2 min recovery | 3 | 45 | 24 | NI |

HRmax = heart rate maximum; HRres = heart rate reserve; MI = moderate intensity; HI = heavy intensity; IT = interval training; NI = no information.

The most commonly reported positive effects on physiologic physical performance indicators were observed in the VO2max/peak, resting heart rate, HRmax, and submaximal heart rate, as shown in Table 2.

Concurrent trainingCharacteristics of the sampleThe initial sample size of the selected studies ranged from 35 (44) to 100 (36). The final sample ranged from 31 (44) to 97 (36), and the mean age of the participants ranged from 18 to 60 years. The studies included patients of both sexes, but there was a predominance of males (70%). All studies analyzed in this review included patients diagnosed with HIV, and most of these patients were receiving antiretroviral therapy.

Characteristics of intervention programsThe exercise intervention characteristics of the included studies are provided in Table 5. The duration of the intervention programs with concurrent training ranged from 6 (38) to 24 (36) weeks, but in most studies, the application period ranged from 12 to 16 weeks. The duration of the session varied from 60 (40,41) to 120 (42) minutes. The frequency of sessions varied from two to three times per week, but there was a predominance of three times per week (72% of studies).

Characteristics of the experimental intervention (concurrent training) in the trials included in the review.

| N | Study | Type exercise | Intensity/duration (wk) | Volume | Frequency (x per Wk) | Time (min) | Length (wk) | Supervision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yarasheski et al. 2010 | Aerobic exercise cycling/treadmill | 50-85% Hres | NI | 3 | 90-120 | 16 | Yes |

| Resistance exercise | 12 RM | 1-2 sets 12 reps | 3 | 90-120 | 16 | Yes | ||

| 2 | Mutimura et al. 2008 | Aerobic exercise | 45% HRmax/3 60% HRmax/6 75% HRmax/15 | 15 min warm-up 60 min exercise 15 min cool-down | 3 | 90 | 24 | Yes |

| Resistance exercise | NI | NI | 3 | 90 | 24 | Yes | ||

| 3 | Hand et al. 2008 | Aerobic exercise | 50-70% HRmax | 5 min warm-up 30 min exercise 5 min cool-down | 2 | 40 | 6 | NI |

| Resistance exercise | 12 RM | 1 set, 12 reps | 2 | 20 | 6 | NI | ||

| 4 | Pérez-Moreno et al. 2007 | Aerobic exercise Cycle ergometer | 70-80% HRmax | 10 min warm-up 20 min exercise 10 min cool-down | 3 | 20-40 | 16 | Yes |

| Resistance exercise | 12-15 RM | 1-2 sets 12-15 reps | 3 | 50 | 16 | Yes | ||

| 5 | Filipas et al. 2006 | Aerobic exercise | 60% HRmax/3 75% HRmax/3 | 5 min warm-up 20 min exercise 5 min cool-down | 2 | 30 | 6 | Yes |

| Resistive exercise | 60% RM 80% RM | 3 sets 10 reps | 2 | 30 | 6 | Yes | ||

| 6 | Dolan et al. 2006 | Aerobic exercise | 60% HRmax/2 75% HRmax/14 | 5 min warm-up 20-30 min exercise | 3 | 35 | 16 | Yes |

| Resistive exercise | 60-70% RM/2 80% RM/12 | 3-4 sets 8-10 reps | 3 | 85 | 16 | Yes | ||

| 7 | Driscoll et al. 2004 | Aerobic exercise stationary bicycle | 60% HRmax/2 75% HRmax/14 | 5 min warm-up 20-30 min exercise 5 min cool-down | 3 | 35 | 12 | Yes |

| Resistive exercise | 60-70% RM/4 80% RM/12 | 3-4 sets 8-10 reps | 3 | 25 | 12 | Yes | ||

| 8 | Driscoll et al. 2004 | Aerobic exercise stationary bicycle | 60-75% HRmax | 5 min warm-up 20-30 min exercise 5 min cool-down | 3 | 36 | 12 | Yes |

| Resistive exercise | NI | 3 sets, 10 reps | 3 | 24 | 12 | Yes | ||

| 9 | Rojas et al. 2003 | Aerobic exercise | 60-80% HRmax | 10 min warm-up 25 min exercise 10 min cool-down | 3 | 50 | 12 | NI |

| Resistive exercise | 60-70% RM/4 80% RM/12 | 2-3 sets 8 reps | 3 | NI | 12 | NI | ||

| 10 | Grispoon et al. 2000 | Aerobic exercise stationary bicycle | 60-70% HRmax | 30 min exercise 15 min cool-down | 3 | 30 | 12 | Yes |

| Resistive exercise dynamic | 60-70% RM/6 80% RM/6 | 2 sets, 8 reps 2 sets, 8 reps | 3 | 12 | Yes | |||

| 11 | Rigsby et al. 1992 | Aerobic exercise | 60-80% HRmax | 2 min warm-up 30 min exercise 3 min cool-down | 3 | 36 | 12 | NI |

| Resistive exercise | NI | 1-3 sets 6-18 reps | 3 | 24 | 12 | NI |

HRmax = heart rate maximum; HRres = heart rate reserve; RM = repetition maximum; reps = repetitions; NI = no information.

For resistance training, only two studies (40,42) specified the type of muscle contraction performed during training. The exercise was performed with concentric and eccentric contractions lasting 6 to 10 seconds with the use of machines, weight stations, and free weights in six studies, but in one study, there was no description of the type of equipment used (36). The exercise intensity was based on the extent of the RM, ranging from 60% to 80% of the RM in five studies (40–42,44),. Three studies described the intensity as the 12RM (35,38,39), and three studies did not report the prescribed exercise intensity (36,43,47). The application volume of exercise ranged from one to four sets of six to 18 reps. The volume of exercise was not described in one study (36).

For the application of aerobic exercise, all studies reported treadmill use, bike use, cycle ergometer use, walking, or jogging. Except for a study by Rigsby (47), all studies reported the criteria for progression training. In all studies, the intensity was adjusted based on the heart rate, ranging from 45% to 80% of the HRmax. The sessions of aerobic exercise began with a warm-up period of 5 to 10 min and finished with a cool-down period of 5 to 15 min. Table 3 provides details on the characteristics of the intervention programs.

Effects of different types of therapeutic exerciseResistance exercise training improved outcomes related to body composition, with increases in lean body mass (13), mid-thigh cross-sectional muscle area (15,19,21), and bone mineral density (13–21), in addition to a reduction in body weight (14). Resistance exercise also generated muscle strength gain (13–21) but had little impact on quality of life (15–18).

Aerobic exercise training improved outcomes related to body composition, reducing body weight (25,29), total body fat (29), and the WHR (25). A significant increase was also observed in aerobic capacity, as measured by the VO2max/peak (25), or time on a treadmill (29).

Concurrent training showed significant gains in body composition, with increases in lean body mass (35,46), thigh muscle volume (35), and mid-thigh cross-sectional muscle area (40,42,46). This training reduced thigh muscle adiposity (43), the percentage of body fat (36,43), and the WHR (42). Significant increases were also observed in muscle strength (39,40,46,47); aerobic capacity, measured by the VO2max/peak (37–40); exercise duration (42,47); and the distance covered in 6 min walking test (40), with a positive impact on quality of life (36,41,44). Thus, in contrast to resistance and aerobic exercise performed in isolation, concurrent training showed improvement for all evaluated outcomes.

DISCUSSIONThe results of this review indicate that resistance training, aerobic exercise, and concurrent training are associated with improvements in body composition, muscle strength, and cardiopulmonary fitness in adults living with HIV/AIDS.

The functional impairments of a patient should determine the exercises and activities prescribed, including the mode of exercise used (48,49). The use of multiple conditioning components to address both neuromuscular strength and cardiovascular health has become an important part of most recommended exercise regimens (50).

It is important to emphasize that exercise training should be supervised by qualified professionals for the prevention of injury and to maximize the health and performance benefits (51). In 80% of the reviewed studies, the supervision of exercise by a professional was reported.

The available literature regarding the effects of exercise training in HIV is encouraging. The published trials indicate that short-term resistance exercise has physiologic benefits and positive effects on body composition and musculoskeletal health (24). Aerobic exercise directly benefits aerobic capacity (32). Concurrent training has a positive effect on body composition, aerobic capacity, muscle strength, and quality of life (38,41).

In a study by Spence et al. (24), the RM was used to evaluate muscle strength. The between-group mean values for lower-extremity muscle function were significantly different (p<0.01), indicating improved muscle performance in the resistance exercise group with 6 weeks of exercise. Stringer et al. (32) observed an improvement in the VO2max after 6 weeks of aerobic exercise. In studies by Hand et al. (38) and Fillipas et al. (41), there was an improvement in the aerobic capacity estimated in the concurrent training group, whereas no improvement was noted in the control group after 6 weeks (p<0.01). Individual studies also indicate that exercise training appears to be safe (52).

Incorporating both resistance and aerobic modalities into rehabilitation programs may be more effective in optimizing functional status than programs involving only one component (53–55). In people with HIV, concurrent exercise training may decrease functional limitations and reduce physical disability resulting from HIV infection and its medical treatment (56,57). Seven studies reported significant improvement in a concurrent training group compared with a control group (35,36,38–44,46),.

In a study by Multimura et al. (36), the VO2max improved in the concurrent exercise group compared to the control (p<0.001). In a study by Hand et al. (38), there was an improvement of 21% in the VO2 estimated in the concurrent training group and no improvement in the control group (p<0.001). In the study by Filipas et al. (41), the HR was reduced in the exercise group compared with the control (p<0.001).

Exercise prescription is based upon the frequency, intensity, and duration of training; the mode of activity; and the initial functional status. The interaction of these factors provides the overload stimulus and has been found to be effective for producing a training effect (58,59).

Determining the appropriate exercise mode depends on patient preference and safety issues regarding the stage of the disease or other conditions. The frequency, intensity, and duration are specific to the type of activity and should be tailored to the patient's ability to safely perform the activity.

A minimal intensity level is likely required to receive a benefit, although the exact value is not known and may vary from one person to another. Although the optimal intensity cannot be defined based on available information, much of the exercise that is associated with good health in published reports is at least of moderate intensity (58,60).

Resistance training should focus on large muscle groups, such as the chest, brachial biceps, quadriceps, and hamstrings. Again, the intensity should be moderate (set at 60% to 80% of the RM) and progressively increased. Overload should be set to match the level at which a patient can comfortably perform eight to 12 reps. For people who wish to focus on improving muscular endurance, a lower intensity (i.e., <50% of the RM; light to moderate intensity) can be used to complete 15 to 25 repetitions per set, with the number of sets not to exceed two (60,61).

Aerobic exercises should be performed at a moderate intensity, from 11 to 14 on the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale, at 50% to 85% of the HRmax, or at 45% to 85% the VO2max/peak. The number of weekly exercise sessions should be increased until the patient can tolerate three to five sessions weekly. In total, 30 to 60 min per day is recommended, although 20 min may be beneficial in deconditioned people (60). In all studies included in this review, the session duration ranged from 30 to 60 min. Sessions should be initiated with a warm-up period and finished with a cool-down period.

The maximum duration of the intervention in the included studies was 24 weeks, with most interventions ranging between 6 and 12 weeks. Thus, the long-term effects of exercise remain unclear.

This review has several limitations, and the results should be cautiously interpreted for several reasons. The results are based on a small number of studies. The differences in endpoints, assessment instruments, and variables of exercise prescription and the limited follow-up in several studies prevent definitive comparisons and quantitative analysis.

Meta-analyses were not performed because of the variability of the characteristics of studies pertaining to exercise and variation between individual studies in the interventions, which included the type of exercise intervention, the intensity of exercise, the length of follow-up to exercise, and outcomes.

In conclusion, considerable evidence currently exists to support a role for different types of exercise in the management of HIV-infected patients. Concurrent training showed significant gains in all outcomes evaluated and is the best type of exercise in patients with disabilities resulting from HIV. Research in the field of exercise training in people with HIV should be focused on providing indications regarding evidence-based standards for exercise prescription and on careful clinical evaluation and exercise-related risk assessment.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONSGomes-Neto M, Conceição CS, Carvalho VO, and Brites C conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. Carvalho VO performed the search and the initial selection of potentially relevant studies. Gomes-Neto M and Conceição CS identified the articles in agreement with the inclusion and exclusion criteria and performed the data extraction. Brites C supervised the review process and resolved disagreements. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.