Spontaneous evisceration through the vagina was first described in 1907 by McGregor.1 To date, only eighty-five cases of transvaginal small bowel evisceration have been documented worldwide.1,2 The primary risk groups for spontaneous vaginal evisceration include postmenopausal women,1,3–7 vaginal surgery cases,1,8–10 multiparae,11 and women of older age.2,3

In postmenopausal woman, transvaginal evisceration is frequently associated with increased abdominal pressure,1 vaginal ulceration due to severe atrophy, and straining at stool.6,8

Vaginal evisceration is a medical emergency that requires prompt recognition and immediate surgical intervention.1 The associated mortality rate is 5.6 percent; however, the incidence of morbidity is higher3,8 when the bowel has become strangulated through the vaginal defect.

Here, we report a case of vaginal vault rupture with evisceration through the vagina and highlight the risk factors, clinical presentation, and treatment options for this rare gynecological emergency.

CASE REPORTA female patient aged seventy-five years was admitted to the emergency room with abdominal pain ten days after an angioplasty plus coronary stent implantation, which had been performed through the femoral artery. Three days after the angioplasty; i.e., one week prior to presentation to the emergency room, an inguinal hematoma developed as complication of the femoral arteriography had to be drained. Thereafter, the patient suffered from constipation and had difficulties with evacuation. On the day the woman presented to the emergency room, she felt a sudden and dull abdominal discomfort during evacuation and noticed a loop of bowel protruding from her vagina. There was no history of abdominal or vaginal trauma.

Thirty years prior to the present admission, the woman had undergone a total abdominal hysterectomy for a benign pathology. The operation had no complications, and the patient’s recovery was uneventful. After the hysterectomy and ten and twelve years prior to the present admission, the woman had undergone two perinea surgeries for a prolapsed bladder. Apart from these three surgeries, the she had no past medical or gynecological history worthy of note.

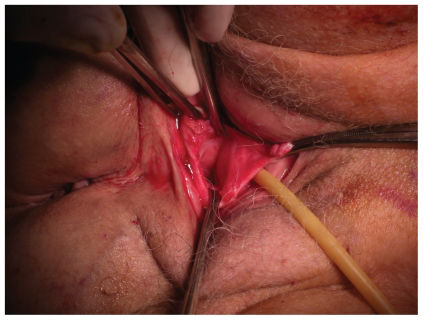

Upon admission to the emergency room, the patient’s blood pressure was 110 × 70 mmHg, her heart rate was 88 bpm, and an abdominal examination indicated significant pain. The pelvic examination revealed 40 cm of small bowel prolapsing through her vagina (Figure 1). After resuscitation of the patient, she received intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics (1 g of Ceftriaxon and 500 mg of Metronidazole), and her bowel was wrapped with warm, sterile, and saline-soaked gauze for transfer to the operating room. There, under rachianesthesia, the woman was placed in lithotomy position, so that the viability of her small bowel could be assessed. The examination revealed that the bowel was edematous and thick-walled, but still viable. There was no evidence of necrosis. The inguinal hematoma, which looked infected, was drained (Figure 2). The patient was then placed in the Trendelenburg position. Because the vault defect was located high in the vagina, all attempts to transvaginally reduce the small bowel into the peritoneal cavity were unsuccessful. Consequently, a midline subumbilical incision was made, and the prolapsed bowel was reduced into the abdomen and inspected for damage throughout its length. Thereafter, the vaginal vault defect was closed with absorbable sutures (Polygleprone 2.0) by a vaginal route (Figure 3), and a 30-cm segment of bowel was excised. Although the bowel was viable, we decided to carry out this procedure because there was an expansible hematoma in the mesum. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were postoperatively given for six days. The patient had no postoperative complications and was discharged from the hospital after six days. In a follow-up examination three months later, the woman exhibited no evidence of recurrence, and the vaginal vault had healed satisfactorily.

Vaginal evisceration is a rare event that has been reported to occur after vaginal traumas induced by coitus, obstetric instrumentation, and the insertion of foreign bodies. Vaginal evisceration has also been reported after pelvic surgery and in patients with enterocele.8 The risk groups for transvaginal small bowel evisceration include the elderly; postmenopausal women;2,7 female patients after vaginal,9,10,12 abdominal,4–6,13 or laparoscopic hysterectomy; 14 and multiparous women.11 Due to the weakening of vaginal tissue caused by genital atrophies and enteroceles, the risk of spontaneous evisceration is increased in postmenopausal women, particularly in combination with straining at stool and/or vaginal ulceration.8,15 Because the postmenopausal vagina is thin, scarred, foreshortened, and has diminished vascularity, it is more prone to rupture.1,4 In postmenopausal women, vaginal ruptures most commonly occur at the posterior fornix.8,16

In postmenopausal women, evisceration can occur either spontaneously or, more frequently, in connection with an increase in intra-abdominal pressure induced by coughing, defecating, or falling.11 In premenopausal patients, evisceration is usually preceded by vaginal trauma caused by rape, coitus, obstetric instrumentation, or the insertion of foreign bodies.1,3,8,16 Additional risk factors for vaginal evisceration include previous vaginal surgeries and enteroceles.8 According to Kowalski et al.2, 73 percent of patients with vaginal evisceration had previously undergone some kind of vaginal surgery, most commonly transvaginal hysterectomies or enterocele repairs. In 63 percent of the reported cases, the patients had enteroceles, which putatively caused further stretching of the atrophic vagina, thus making it more susceptible to rupture. Of all the eighty-five cases of vaginal evisceration reported in the literature to date,8 50–75 percent of the patients had undergone one or more previous vaginal operations,3,8 and roughly 25 percent of the eviscerations occurred after abdominal hysterectomy.2 Postoperative cuff infections after hysterectomy have also been shown to contribute to evisceration.13 So far, there are no reported cases of vaginal vault rupture and evisceration due to perineal proctectomy or rectal prolapse.

In the present case, one of the underlying causes of the evisceration was probably the fact that the patient was a postmenopausal woman with previous history of pelvic surgeries (hysterectomy and perinioplasty), which putatively had weakened her pelvic floor and consequently contributed to the vaginal rupture. A second cause for the evisceration was excessive strain due to the difficulty in evacuating in the presence of a retroperitoneal hematoma.

Vaginal evisceration is a surgical emergency, and immediate recognition and surgical repair are crucial for its successful management. The appropriate management of evisceration includes a thorough assessment of the herniated viscus and surgical repair of the vaginal defect. In cases where the eviscerated bowel is viable and can be reduced into the peritoneal cavity without complication, the closure of the vaginal defect can be accomplished by a vaginal approach;2 however, in patients with minimal or no enterocele, the vaginal defect may be located high in the vagina, as was the case in the present study. Under these circumstances, a vaginal approach is not viable because the bowel, which becomes trapped and strangulated after protruding through the defect, prevents access to the defect itself. In these cases, laparotomy is necessary to access the defect, reduce the bowel into the abdomen, and resect any nonviable bowel. To date, all the reported cases that have required bowel resection have been managed with exploratory laparotomy followed by repair of the vaginal defect.2,17 A combined abdominal and vaginal surgical approach, as the one used in the present case report, is recommended for adequate evaluation and effective repair of the tissues involved.11