Insulin resistance (IR) leads to insulinemia >1000IU/dl for normal glucose levels; its prevalence in childhood ranges from 3.0 to 8.4%.1

The underlying etiopathogenesis may be primary (gene mutation) or secondary (obesity and/or lipodystrophy).2

Hereditary IR may be classified as polygenic IR of moderate severity, which is characteristic of type 2 or monogenic diabetes; IR associated with syndromes characterized by a phenotype with centripetal obesity or lipodystrophy; or IR associated with isolated hereditary receptor disorders3 such as the following:

Leprechaunism or Donohue syndromeThis disorder is a complete autosomal recessive insulin-receptor binding defect resulting in a loss of insulin action. It manifests as early postprandial hypoglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, hyperlipidemia, delayed intrauterine growth, dysmorphic alterations, decreased subcutaneous adipose tissue and muscle mass, macrogenitalism, and ovarian cysts. Death commonly occurs before two years of life, due to intercurrent infections.4

Rabson-Mendenhall syndromeThis syndrome constitutes an incomplete insulin receptor-binding defect. It includes excessive insulin production and difficulties in removing insulin from the bloodstream. The syndrome is characterized by an autosomal recessive hereditary pattern, and the genotype predicts the phenotype.5 Patients with Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome present hyperinsulinemia, postprandial hyperglycemia followed by early hypoglycemia, constant ketoacidosis, hyperlipidemia, delayed growth, muscle dystrophy, dysplastic and premature teeth, gingival hypertrophy, and pineal gland hyperplasia. Mortality is related to a patient tendency towards ketoacidosis, and microvascular complications.4,6

Type A insulin resistance syndromeThis syndrome is characterized by decreased insulin receptor binding and signaling. The phenotype is conditioned by insulin resistance, genetic mutations and associated environmental factors.5 The disorder manifests as glucose intolerance, hyperandrogenism, high body height, and a thin and muscular body constitution.4

Insulin acts differently in the different tissues. The symptoms that may be associated with IR according to the severity of the mutation are5–7:

- •

Acanthosis due to the toxic insulin effect upon the skin.

- •

Hyperandrogenism due to premenstrual testosterone overproduction.

- •

Early puberty due to gonadotropin and insulin synergy.

- •

Hypertriglyceridemia and fatty liver secondary to selective binding to the hepatic -insulin post-receptor, inducing lipid synthesis and secretion in the liver.

- •

Pseudo-acromegaly due to lax tissue overgrowth secondary to a post-receptor mutation.

- •

Alterations in linear growth.

- •

Postprandial hypoglycemia with secondary reactive hyperglycemia.

- •

Centripetal obesity or lipodystrophy due to leptin deficiency or a mutation of adipocyte differentiation and regulation, promoting muscle dystrophy.

The decrease in tyrosine kinase activity and diminished insulin binding to receptors are reversible with weight loss.6

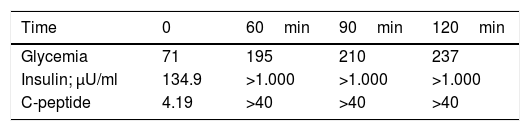

We report the case of an 8-year-old male with a one-week history of polyuria, polydipsia, hyperglycemia (319mg/dl) and glycosuria, without ketonemia. This was a preterm child with no delayed intrauterine growth. The family history comprised a mother with breast cancer, gestational diabetes and subsequent type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with oral antidiabetic drugs, and a grandfather with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Examination showed a body weight of 41.5kg (p53), height 141cm (p56), a body mass index (BMI) 20.3kg/m2 (p52), and the absence of acanthosis nigricans. The laboratory tests in turn revealed anti-GAD antibodies, anti-insulin antibodies and anti-IA2 antibodies; the study of gene GCK and HNF1A proved negative (HNF4A testing was not performed, because the technique was not available at our hospital). Basal C-peptide: 4.19ng/ml, measured by chemiluminescence. Insulin therapy was started and discontinued after one year. The patient was lost to follow-up, but was seen again 5 years after the diagnosis, with glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) 7.7 %, sustained postprandial hyperglycemia, sporadic preprandial hypoglycemia and acanthosis nigricans, despite having maintained a normal BMI since diagnosis (21.23kg/m2). The patient presented a glycemia-insulin-C-peptide curve with insulinemia >1000μU/ml, performed by radioimmunoassay (Table 1). A peripheral blood leukocyte DNA study was made of the 22 exons of gene INSR, with direct sequencing (3700 ABI), revealing a heterozygous alteration in exon 20 (p.Asp1177Glu, C.3531C>G), the same mutation carried by the mother and grandfather (mother BMI 19.7kg/m2; grandfather BMI 22.9kg/m2). This is a mutation located in the beta chain, consistent with type A insulin resistance syndrome, and currently treated with metformin, with good glycemic control (HbA1C 6.5 %).

Type A insulin resistance syndrome is characterized by moderate to severe IR in the absence of obesity or lipodystrophy, as in our patient. Because of its subtle clinical signs, particularly in childhood, this syndrome is underdiagnosed in the pediatric population.4

The diagnosis of IR is based on a good anamnesis, the monitoring of glycemia and laboratory tests, and a genetic study.4

Type A insulin resistance is related to mutations of the INSR gene. Our patient presented a non-described mutation, with good genotype-phenotype correlation according to the in silico5,7 studies. This is a heterozygous mutation located in the beta chain of INSR, which functional studies have associated with a milder IR phenotype such as that found in first and second degree relatives of our index case.7

Insulin sensitizers are used as first choice treatment to lower insulinemia, as in our patient. Insulin is sometimes required. Recombinant IGF1 improves survival in neonatal presentations of the disease.4

In our case mention should also be made of the history of maternal breast cancer, since insulin resistance has been related to cancer development because of the similarity between insulin receptors and growth factor receptors.8–10 Increased IGF1 and IGF2 receptors induce changes in receptor dimerization (iso-receptors A and B) and a cascade of highly potent activating signals that increase endometrial and breast proliferation through the activation of sex hormones, while decreasing the metabolic response and apoptosis.

An alteration in the iso-receptors A:B ratio has been observed in tumors with an increase in isoform A and a decrease in isoform B that has been related to the level of proliferation. This can be used as a prognostic and treatment response biomarker, since majority iso-receptor B carriers are resistant to tamoxifen, with increased cell proliferation and metastasis, as well as mutagenesis and carcinogenesis secondary to an increase in free radicals and DNA damage.10 By contrast, the predominance of subtype A is associated with a good treatment response and lesser proliferation.9,10

Finally, an increase in adipose tissue results in an increase in inflammatory cells, activating the said inflammatory system and promoting tumor production.8

Further studies are needed to reinforce these theories.

Please cite this article as: Ariza Jiménez AB, López Siguero JP, Martínez Aedo Ollero MJ, del Pino de la Fuente A, Leiva Gea I. Mutación del gen INSR. Insulinorresistencia poco prevalente en edad pediátrica. A propósito de un caso. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2019;66:588–589.