As leprosy is a rare chronic disease in our setting, especially in the paediatric population,1 we present a case report that we consider of interest.

This was a girl referred to the paediatric infectious medicine clinic while her father, of Brazilian origin, was having tests for non-erythematous, non-pruritic, non-painful infiltrated skin lesions on his chin, pinnae and nose; these were associated with multiple erythro-pigmentary macular lesions on his trunk and limbs, and numbness in the distal region of the left leg.

Our three-year-old patient, born in Spain and with no medical history of interest, had a ring-shaped lesion with a raised, erythematous border and a flatter, hypopigmented centre, 5 cm in diameter, on the medial aspect of her left forearm (Fig. 1). The lesion had been there for a year and had not responded to topical corticosteroids. The decision was made to biopsy the lesion.

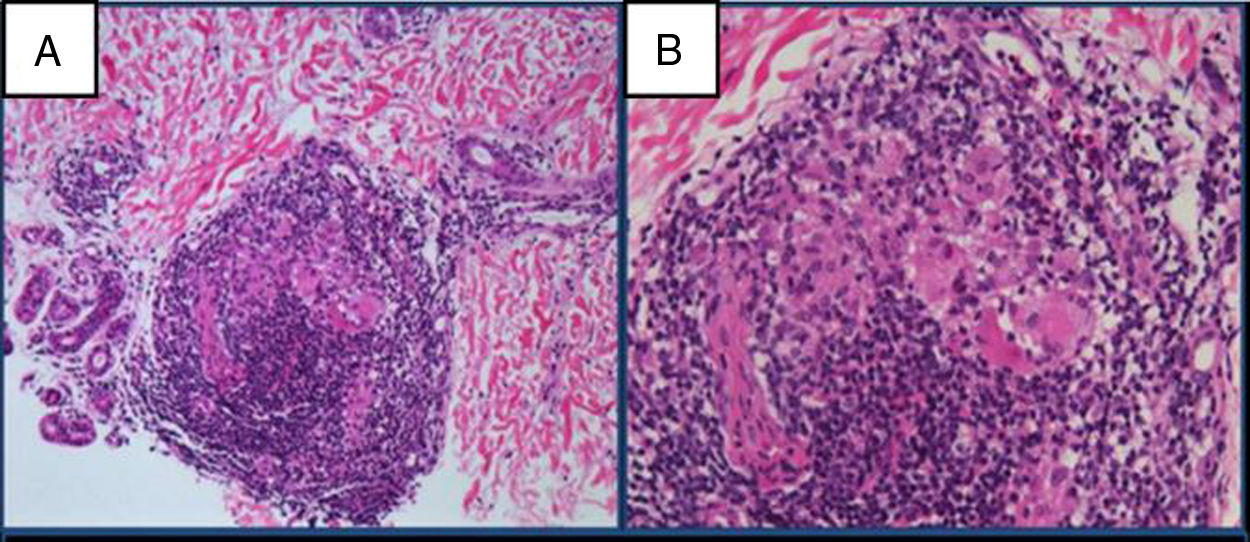

The pathology report confirmed the presence of chronic, granulomatous nodular inflammation, with giant cells and a perivascular, periadnexal and perineural lymphocytic crown (Fig. 2). It was stained with the Fite-Faraco technique, with no bacilli observed. A sample of the biopsy was sent for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Mycobacterium leprae (M. leprae) with M. leprae-specific-repetitive-element PCR positive, M. leprae Ag 18-kDa PCR positive and GenoType Leprae-DR negative. Nasal exudate smear microscopy was negative.

Both clinically and bacteriologically, this seemed to be a case of paucibacillary leprosy, according to the WHO classification, or tuberculoid leprosy (pathologically), one of the most common forms in childhood. Treatment was started with rifampicin (15 mg/kg/dose monthly) and dapsone (2 mg/kg/day) for six months.

A skin biopsy was also performed in the father, who had a dermal histiocytic infiltrate with acid-alcohol-fast bacilli compatible with leproma, and he was diagnosed with lepromatous leprosy.

Leprosy in children is an epidemiological indicator of active foci in adults and recent transmission.2 Diagnosis is difficult, even in countries with a higher prevalence of leprosy (Brazil, India).3 In Spain, 168 cases of leprosy were diagnosed from 2003 to 2013, with 128 foreign patients; mainly (71.9%) from South America (Brazil).4 In our setting, a high degree of clinical suspicion based on an adequate epidemiological investigation is necessary to arrive at the diagnosis. The route of transmission is not very clear, but it is believed that the contagion is by respiratory secretions and not by contact with the skin lesions.

According to the Ridley-Jopling classification (based on the patient's clinical and immunological status), two main forms are described5: tuberculoid leprosy, one or a few hypo- or hyper-pigmented lesions with or without loss of sensation; and lepromatous leprosy, with multiple skin lesions and nerve involvement. Between these two forms there is a broad clinical spectrum (borderline-tuberculoid, borderline-borderline and borderline-lepromatous). In the cases tending towards lepromatous, the histology shows inflammatory infiltrates with Virchow cells full of bacilli and absence of appendages. The tuberculoid polarity involves tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells, Langerhans cells and lymphocytic infiltrates with the absence of bacilli. According to the WHO, leprosy is classified as paucibacillary (1–5 skin lesions, only one affected nerve trunk, negative smear microscopy) and multibacillary (>6 skin lesions, more than one affected nerve trunk and positive smear microscopy).

Key to microbiological diagnosis is a skin biopsy, which enables the presence of bacilli to be visualised by Fite-Faraco staining. It has not been possible to isolate M. leprae in the usual culture media for mycobacteria. Smear microscopy has a specificity of 100% and a sensitivity of 50% in samples of nasal mucosa, earlobe and skin lesions. In tuberculoid (paucibacillary) leprosy, bacilli are very difficult to detect and genome amplification (PCR) techniques for the detection and identification of M. leprae have meant a significant advance in these cases.6 The sensitivity of PCR in paucibacillary forms is from 50% to 80%. The GenoType Leprae-DR technique also makes it possible to analyse resistance to rifampicin, quinolones and dapsone.

The WHO recommends combined therapy7; double therapy with rifampicin and dapsone in paucibacillary forms for six months and, in multibacillary forms, adding a third drug (clofazimine) and prolonging the duration of treatment to 12 months. Chemoprophylaxis in cohabitants is not indicated.

In this case, we wish to highlight the importance of studying contacts who live with leprosy patients, especially with multibacillary forms, as leprosy is a curable disease if properly treated and this prevents transmission to other people.

FundingNo funding was received for the preparation of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest.

To Dr Juan José Palacios Gutiérrez, Medicine Laboratory, Microbiology Section, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, for the molecular diagnosis of M. leprae.

To Dr José Ramón Gómez Echevarría, Medical Director of Lepra Fontilles, director of Leprology courses, for his help with the clinical orientation, diagnosis and treatment of the case.

To Dr Joanny Alejandra Duarte Luna, Pathology Department, Hospital Universitario de Getafe, for the pathology diagnosis on the skin biopsy.

Please cite this article as: Berzosa-Sánchez A, Soto-Sánchez B, Cacho-Calvo JB, Guillén-Martín S. Lepra tuberculoide, todavía presente en nuestro medio. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2020;38:344–345.